“medicine that gives you direct access to your deities and healing from within”

Amy is joined by Alicia Galbraith & BreAnna Larson to begin their discussion of the plant medicine peyote. This episode is Part One of Two and covers the history of peyotism among Indigenous communities and what drew our guests to participate in a peyote ceremony.

Our Guests

Alicia Galbraith

Alicia Galbraith is passionate about mental health. With a background in neuroscience, yoga, and meditation, she is currently pursuing a Masters Degree in Social Work with the intent to become a therapist. She believes each client she meets with has the tools for their own healing within themselves. In sessions, she pulls from her varied background, clearing the path for whole-person healing, with the firm belief that each client holds their own medicine.

BreAnna Cox Larson

BreAnna Cox Larson lives in North Salt Lake with her husband and four kids. She is the Chair of the NSL Planning Commission, the Co-founder and Chair of the Davis County Women’s Caucus, and a member of the Stakeholder’s Committee for the Davis School District. She volunteers as a citizen lobbyist with a focus on empowering citizens to get involved in their communities through boards and commissions to impact municipal-level change. She and her family own a small hobby vineyard and enjoy skiing and riding motorcycles together.

The Discussion

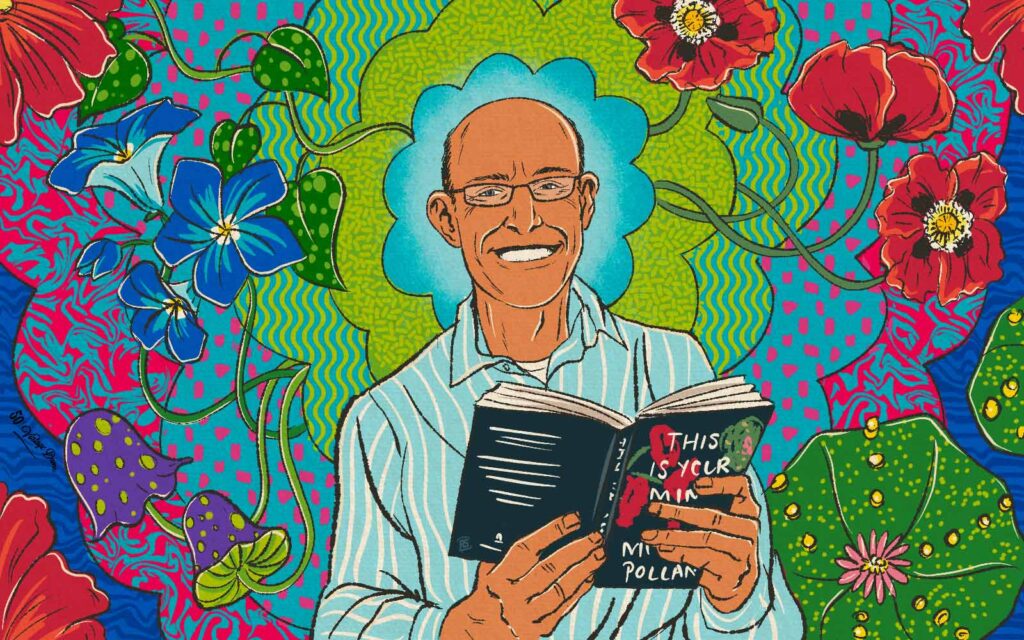

Amy Allebest: You may have heard of the journalist, science writer, and Harvard professor, Michael Pollan. He’s the author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma in 2006, How to Change Your Mind in 2018, and most recently, the book This is Your Mind on Plants in 2021, from which I would like to read a quote. He says this:

“Of all the many things humans rely on plants for–sustenance, beauty, medicine, fragrance, flavor, fiber–surely the most curious is our use of them to change consciousness: to stimulate or calm, to fiddle with or completely alter, the qualities of our mental experience. Like most people, I use a couple of plants this way on a daily basis. Every morning without fail I begin my day by preparing a hot-water infusion of one of two plants that I depend on (and dependent I am) to clear the mental fog, sharpen my focus, and prepare myself for the day ahead. We don’t usually think of caffeine as a drug, or our daily use of it as an addiction, but that’s only because coffee and tea are legal, and our dependence on them is socially acceptable. So then, what exactly is a drug? And why is making tea from the leaves of Camellia sinensis uncontroversial, while doing the same thing with the seed heads of Papaver somniferum is, as I discovered to my peril, a federal crime?

…an illicit drug is whatever a government decides it is. It can be no accident that these are almost exclusively the ones with the power to change consciousness. Or, perhaps I should say, with the power to change consciousness in ways that run counter to the smooth operations of society and the interests of the powers that be. As an example, coffee and tea, which have amply demonstrated their value to capitalism in many ways, not least by making us more efficient workers, are in no danger of prohibition, while psychedelics–which are no more toxic than caffeine and considerably less addictive–have been regarded, at least in the West since the mid 1960s, as a threat to social norms and institutions.

But even these classifications are not as fixed or as sturdy as you may think. At various times both in the Arab world and in Europe, authorities have outlawed coffee, because they regarded the people who gathered to drink it as politically threatening. As I write, psychedelics seem to be undergoing a change of identity. Since researchers have demonstrated that psilocybin can be useful in treating mental health, some psychedelics will probably soon become FDA-approved medicines: that is, recognized as more helpful than threatening to the functioning of society.

This happens to be precisely how Indigenous peoples have always regarded these substances. In many Indigenous communities, the ceremonial use of peyote, a psychedelic, reinforces social norms by bringing people together to help heal the traumas of colonialism and dispossession. The government recognizes the First Amendment right of Native Americans to ingest peyote as part of the free exercise of their religion, but…the rest of us do not enjoy that right, even if we use peyote in a similar way. So here is a case where it is the identity of the user rather than the drug that changes its legal status.

…There is scarcely a culture on earth that hasn’t discovered in its environment at least one such plant or fungus, and in many cases a whole suite of them, that alters consciousness in one of a variety of ways. Through what was surely a long and perilous trial and error, humans have identified plants that lift the burden of social pain; render us more alert or capable of uncommon feats; make us more sociable; elicit feelings of awe or ecstasy; nourish our imagination; transcend space and time; occasion dreams and visions and mystical experiences; and bring us into the presence of our ancestors or gods. Evidently, normal everyday consciousness is not enough for us humans; we seek to vary, intensify, and sometimes transcend it, and we have identified a whole collection of molecules in nature that allow us to do that.”

And that’s the end of that very long quote. But I wanted to share that excerpt from Michael Pollan’s book as an introduction to a series on indigenous plant medicine that we’ll be doing on the podcast. Today we’ll be starting this series with a discussion of what Native Americans refer to as Grandfather Peyote. And then our next two discussions will feature the psychedelic plant medicine ayahuasca, traditionally called Mamá Aya. And I’m so excited to start this series with a conversation with the brilliant Alicia Galbraith and BreAnna Larson. Welcome, Alicia and Bre!

BreAnna Larson: Thank you, Amy. Glad to be here.

Alicia Galbraith: Thank you so much.

AA: As we usually do, we’ll start with your professional bios first, and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourselves more personally afterwards. So we’ll start with BreAnna Larson. BreAnna Larson left a piece of her heart and her career as a dental hygienist in New York City over a decade ago to follow a path out west with her husband, where she has found empowerment and community. She currently serves as the chairwoman of the North Salt Lake City Planning Commission, as well as the chairwoman and co-founder of the Davis County Women’s Caucus. She is passionate about creating and preserving equitable and sustainable environments that promote connection and community. She finds her greatest joy and personal alignment from being a mom to dogs, cacti, and humans, fostering and rehabilitating kittens for adoption, working as an integration coach, and officiating weddings. And again, welcome BreAnna.

BL: Thank you, Amy. So happy to be here.

AA: Alicia Galbraith has a master’s in neuroscience from Columbia University in New York City and worked in research on her winding path to Utah. Luckily, she picked up BreAnna’s friendship along the way, so it was a fair trade. Along this winding path, Alicia also picked up a few injuries and came to yoga and meditation as tools for coping, but ultimately stayed for the peace, connection, and a framework for life. She is a certified meditation instructor and registered yoga teacher and is starting a master’s in social work program with the intent to become a therapist who integrates somatic, nervous system, and mental health through talk therapy, yoga, breath work, and mindfulness for whole person healing. She is an intern at Sol Vista Counseling and is accepting new clients. Welcome, Alicia! And again, I’m so excited you’re both here. Maybe we can start with one of you. You can choose who goes first, but just tell us a little bit more about where you grew up and what makes you who you are.

AG: My name is Alicia Galbraith, and I’m so happy to be here. My ancestry comes quite a bit from European lineage, so there’s German as well as Polish and English. And then also I have Native American ancestry through the Diné Navajo tribe, as well as the Kaibab Paiute tribe. I am originally from Washington State, the oldest of six children in a very devout Mormon home. My upbringing was quite orthodox in the Mormon church. I grew up, went to college, and became extremely passionate about neuroscience. Like how a lot of people feel about humanities and poetry, I found myself feeling about neuroscience. And I really chased that road for a long time. After graduating, I was trying to decide if I wanted to go to med school or get a PhD. And I figured if I got a master’s degree in neuroscience, that might give me a little bit of time to decide, while I was in the fork in the road, if I wanted to go research or med school. And as I graduated, I actually walked across to get my diploma from Columbia, I had just had my first child and at that point in time, I found some deeply embedded scripting from my upbringing to make sure that I did not use my degrees in any kind of professional capacity once I had had children. So I ended up staying home with my children for a number of years. And I actually found a lot of joy and satisfaction in that and really, really loved that for quite some time.

Through a series of injuries, maybe ten years later, I discovered yoga and meditation to try and cope with some long-term chronic pain and cognitive things that I was going through. At the same time, I also began a very long and painful descent and exit from the Mormon church and began years in therapy. And I started to see this intersection between mental health, as we see it currently, with talk therapy and psychology and where that intersected really powerfully with yoga and yogic philosophy as well as meditation and Buddhism. And so that yogic philosophy and meditation and Buddhism really offered a framework for spirituality and connection to myself when I felt like I was in a free fall physically and spiritually. And so I began diving deeper into this and I realized that the healing I was seeking was not a destination. It was something that I needed to learn to walk with, and that the physical and mental domains are intertwined.

So as I continued on this journey, I became a certified meditation instructor and a registered yoga teacher. And with my background in neuroscience, I started to really see how these started to intersect. I felt like that was a great launching pad to move into the world of therapy and find a space where all of those things were integrated. Because trauma and pain often don’t just live in our conscious mind, they exist in our body and in our nervous system. And so my greatest dream is to become a therapist who utilizes research-backed modalities in neuroscience, along with yoga, yogic philosophy, meditation, breath work, and talk therapy, along with other somatic techniques like EMDR and IFS and that sort of thing. And, as you mentioned in my bio, I am working at Sol Vista Counseling up in Alpine and I am actually accepting new clients. So if there’s somebody who feels like this style resonates with them, feel free to reach out. My husband is actually in this space as well, deeply passionate about therapy and multiple modalities leading to healing. And he’s opening a clinic called Etherios Therapy. You can find out more at etheriostherapy.com, and they serve both Utah County and Salt Lake County.

the healing I was seeking was not a destination. It was something that I needed to learn to walk with…

AA: That’s fabulous, Alicia. I know probably a lot of listeners can relate to this, but sometimes when you find yourself looking for a therapist and you have ideas of what you’re looking for, just plugging them into Google and hoping you’ll find somebody that aligns with your values and your needs is really hard. So I appreciate having those recommendations. That’s fantastic. And thank you so much for that intro. Okay, BreAnna, take it away.

BL: Hi, I’m glad to be here. My name is BreAnna Larson and my ancestry is Dutch and English, immigrated here to America in the 1880s. And I grew up in Utah, Davis County specifically. I grew up LDS, what I would now call Orthodox-adjacent. I was the fourth of five children to a convert mother who became a single mother when I was three years old. She was Episcopalian prior to her conversion to Mormonism. And Episcopalians ordain women, and so her religious heritage empowered women. And then after my dad left the house, they were not married for very long, just long enough to have kids, then she was out on her own. She didn’t really have a Mormon mentor to show her the ropes of what female Mormonism looked like. She had no other family members that converted with her. And so in our home, she was raising us with more Episcopal spirituality rather than Mormon spirituality because it’s what she knew. So she was praying over us and empowering us to be spiritual beings. And she would not have said that she was a feminist, but she was definitely raising us to be feminists.

I had assumed that her experience in the church and as a child watching her experience in the church was the female experience in the church. She was the head of our household and was always spoken to, because there was no man to speak to next to her. And then as I got married, I slowly watched myself kind of disappear next to my husband’s maleness, or head of household. And it was a really unsettling feeling for me because I had not seen that in my childhood at all. So as I started to have fewer people talk to me directly, and come with inquiries about our home or our household to me and went straight to my husband, I started to be really unsettled with where my role was going to be spiritually. I went on to have three sons and a daughter, and I worked really hard to try and carve out a path for us that would be able to keep us connected to the religion of my childhood, but also keep me connected to my children. As I was raising my boys, as they were coming into some of the ages in Mormonism where you have different ordinations, I realized that I was going to be amputated from their spiritual path. And that that was the path for me, was to be removed from them and to create a dynamic where they would relate mostly to their father, and that over time the two of us would seem like such differing beings that we would not be even relatable to each other. So through that journey I ended up finding my own power, ordaining myself, reclaiming some of the power that was taken from me, and then in that process, learning about what power really is and keeping my own, and trying to teach people to keep their own and constantly giving it back to people in the areas that I work and the places that I serve. So that’s the background on me.

AA: Thank you so much for those introductions. As we said at the beginning of the episode, the discussion today is going to be about Grandfather Peyote. I’d love for you to introduce the topic by talking about what got you interested in plant medicine in general, and then we’ll go from there.

BL: My road to plant medicine started nagging me when I became more and more aware of the problematic dynamics of a male exclusive priesthood ordination, and primarily how that was disconnecting marriages and families and myself from my husband and my children. I followed that nagging to the organization Ordain Women, who I actively worked with for many, many years. And I eventually came to the realization that I was no longer looking for or would be satisfied with the idea of an ordination that came down through a male line. And so I parted ways with Ordain Women, and thanked them for all that they had empowered me with and taught me with. And through the path of searching for female empowerment, I found the book Mary Magdalene Revealed by Meggan Watterson. And in the book she talks about Thecla from the Bible, and that story just grabbed onto me and would not let go of me. The story of Thecla is a woman who heard the Apostle Paul speaking and so desperately wanted to join this Christian movement and be baptized, and the Apostle Paul told her that she needed to be patient and she couldn’t be baptized at the time. So she ended up baptizing herself, which was totally unheard of and not sanctioned. And nobody gave her the power to do that, but herself. So the story of Thecla is of a girl who becomes her own. And that was the path that I was on.

So eventually, as I was leaving this idea that I really wanted ordination through the Mormon church that would come through male prophet, I realized that I should just ordain myself. And so I went online and read about ordination, and I had no intention at the time of using the ordination, but I wanted to feel like I was taking back my power and use that as kind of a marker of my belief that power comes from within and leaving the trail of that power would be bestowed upon me externally at the time. So I ordained myself, and through that process I started officiating weddings. And as I started to do that, I realized that what was behind so much of the power that I had seen in the priesthood and in the patriarchy was people taking power from people and using it to wield their own intentions and desires. So when I would go into these weddings, people would thrust this power upon me and I would just reject it. And I was saying “You made this marriage. This marriage is already here. And I’m going to do some work to make it legal, but don’t give that to me. That is yours to hold, you created this marriage, and all of that power belongs to you.”

So when I started to see that I saw this play with power so differently, and I was ripe and open to seeing some of those things differently, and then that pulled me in to do my own work of deeply healing my spiritual wounds and some of the spiritual language that I had been given. And then plant medicine became the path for me to do that, where I had to outsource the least amount of my power to somebody else in order for me to connect to that divinity within myself. So that is kind of the path that brought me into plant medicine.

AA: Okay, thank you. So you had this realization and you’re open. What was it specifically that made you think “okay, the next step for me is plant medicine”?

BL: Definitely. The thing that made me think the next step for me was plant medicine is that through the arc of ordination I had realized how much outsourcing of power people do. And so as I wanted to understand that for myself, every other avenue that I looked into had a mediator or an intercessor, whether it was a therapist or a yoga teacher or a sound bowl player. And so plant medicine came to be what seemed like the most salient way for me to ask myself that question without anybody else telling me what was real and what I should expect to have happen. And so I wanted to ask myself that question of what that experience was, for and by myself, without somebody else manipulating it in any way. And as I looked at different modalities of that, the experiences that I had heard from other people of plant medicine seemed like the closest way for me to connect to my own consciousness and get those answers for myself.

AA: Wonderful. All right, Alicia, your turn.

AG: My road to plant medicine started many years before I knew that it started. Many, many years ago, over a decade ago, my husband and I had a friend that we were very close to, we adored, and who had had quite a few challenges in his life. And he began to sit with plant medicine. He would go to other countries, other states. And in real time, we were watching the way that plant medicine was transforming and changing his life, seemingly at a core, personal, cellular level. And it was really inspiring. And at the time, my husband and I were very orthodox in our religion and had no framework in which to put this transformation that we had seen. There was no place for us to explain what we were witnessing. And even though it was many, many years before I would begin my own journey to center or delve into my own shadow work or the language of my subconscious, I think if I chase it all the way back to that point, I was feeling tendrils of a pull toward plant medicine. I knew that eventually it would be part of my story, even though at the time it didn’t fit within any part of my own personal framework, and so I felt distant from it.

And then as I began my journey to disentangling who I was separate from the Mormon church many years later, as so often happens, I began deconstructing everything. And then that road, of all places, which I did not see coming, led me to plant medicine. And I think that what I couldn’t see a decade or so earlier, was that that call that I was feeling was this deep part of me, that it was my authentic self calling me to step into my own power and be my own teacher and salvation when I was ready. And I couldn’t recognize it at the time because I really had no experience with my own inner authentic self. I didn’t have any data points, so I had never really heard my own inner voice or knowing. But that’s what plant medicine does. It connects you directly, like Bre was saying, to your most core, authentic self. And I think there was some part of me that knew that that is what I needed.

my authentic self calling me to step into my own power and be my own teacher and salvation

AA: Well, wonderful. I know that the two of you have a lot of personal experience and also expertise from a lot of reading that you have both done, and I’ve really learned a ton from you. And I know we could dive in on a lot of different topics and actually a lot of different plants, a lot of different plant medicines. But I wanted to ask you specifically for the purpose of this series on the podcast, balancing the masculine and the feminine, we’ll also have episodes on Mother Aya, that’s considered to be feminine. And so specifically I wanted to ask you both about Grandfather Peyote, which is considered to be a masculine medicine. And so, we’ll focus our conversation today on a specific journey, a specific experience that you both had with Grandfather Peyote. And I wonder if we could start by having you tell us what it is. What is peyote? What are the scientific properties and the cultural practices, and a little bit of the history that actually intersects with patriarchal oppression, interestingly. So if you can just introduce us to Grandfather Peyote.

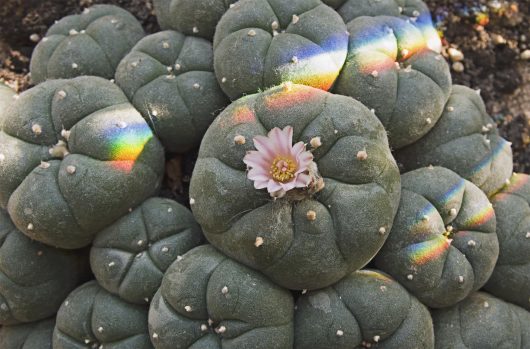

BL: Great. I am just going to introduce us a little bit to the history of peyote, and then Alicia is going to talk about the suppression in the United States with peyote. I’m going to start with the name. The name peyote came from the Nahuatl tribe’s word peyotl, which means caterpillar, cocoon, or to glisten. And when you’ve had an experience with peyote, both of those make perfect sense, although they don’t seem related at all. The active ingredient in peyote is mescaline, which is closely related to MDMA. It’s an organic compound called phenyl ethylamine, which differs from LSD and psilocybin, which are tryptophans, and engages with your brain chemistry just a little bit differently than those other plant medicines. So although it is considered a psychedelic, it does function in your brain a little bit differently. Peyote has been traced back over 5,700 years being used for both entheogenic, which is connecting yourself to God, and medicinal purposes. It has antimicrobial properties and has been used for everything from wound healing, to coming of age vision quests for youth in these tribes, to helping reintegrate warriors back into their tribes after battle. All around it is an excellent healer and is used in many, many ways to help people stay connected to themselves and to the people around them.

Psychedelics often have a signature or a personality that is similar to how they grow, and peyote is no different than that. It is a spineless cactus, it’s very unassuming, it’s slow to grow and slow to find. There is a legend of sorts that peyote is really hard to find until it’s not, and that it has a very playful personality of kind of a hide-and-seek dynamic, which is very similar to how peyote works with a person. Peyote is endangered because of both people digging out the cactus from the roots, which kills it, and also from wild animals consuming it. And there are other plants that can access mescaline, one of them being San Pedro. So there are many routes to get to the mescaline experience while still being aware and respectful of the endangered nature of peyote and also its heritage. When it’s harvested, peyote is cut off from the stem, very close to the ground. And those small parts of the cactus are called buttons, and they administer them in many different ways. In a peyote ceremony, it will typically be distilled down into a tea or a paste. And that is a little bit of the background on how it grows and kind of the personality of the plant.

AG: Like Bre said, peyote has been found in caves. They have actually found buttons that date back 5,700 years and still have 2 percent mescaline in them. So, you could potentially sit with those very ancient buttons and have a mystical experience or a psychedelic experience even now. They are the oldest known plant psychedelic compound. The Huichol are the indigenous people of Mexico who are the direct descendants of Aztecs, and there is archaeological evidence of Aztecs utilizing peyote. To the Huichol, peyote is considered one of their main and sacred deities in their religion. Grandfather Fire also plays a large role, which we’ll talk about later when we talk about the ceremony. Grandfather Fire and Grandfather Medicine work together for the healing and the transforming. Peyote in the Huichol religion or culture is considered “the soul of their religious culture and visionary sacrament.” And that’s a quote from Stacy Schaefer’s book, People of the Peyote. It was used by a number of different indigenous tribes throughout North, Meso, and South America for thousands of years. And like Bre said, it was used for everything from wounds to snake bites to psychological, spiritual things. It seems to have many, many uses.

And in the early 1600s, when the Spanish Inquisition was spreading across parts of South America, the Spanish started to become exposed to peyote for the first known time that we have recorded. And they immediately assumed that these people’s visions and that their religion was diabolical and somehow contacting the devil, which we see throughout history a number of times when Western Christianity meets another religion. And this really emboldened them and created more division. Even though some Spanish soldiers and people were trying peyote and sitting with it, and were finding that it actually merged with their Christian beliefs – some of them would have visions about Christian entities visiting them, or Jesus visiting them – it still scared their leaders even more and galvanized this divide. And so in 1620, peyote was banned by the Spanish during their inquisition. And you can see religiously how it was very threatening to these colonizers. And like we talked about earlier, they were coming in with a religious system that was based on access to deity coming exclusively through a person outside of yourself and usually having authority over you. As well as bumping up against these civilizations whose entire spirituality and religion was based on sitting with medicine that gives you direct access to your deities and healing from within. And so that was just not going to work with their framework. But peyote still continued to be used in other areas of the American continents.

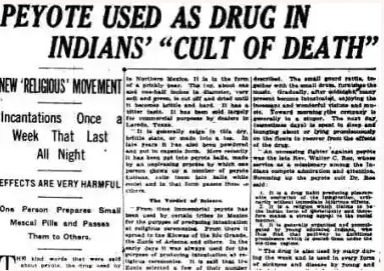

In the 1800s, we started to see the expansion of colonization in the United States really ramp up, with targeted erasure of Native American culture and their religions, their traditions, their language, et cetera. The US government saw the path to civilization, which is code for assimilation, of the Native Americans through Christianity. So Christian missionaries really seized on this and worked with the federal government in many ways to try and get the Native Americans to assimilate into US culture. And one of those ways that kept coming up for a hundred or more years, was to try to eradicate completely what they called peyotism. And that was sort of the term of the Christian missionaries for people who used peyote. And the missionaries saw, and we see this happening hundreds of years later, these missionaries saw the Native American ceremonies as heathen or vile, taking them backwards away from progress. And we have many documents that show their complaints that essentially, as long as Native American tribes had peyote, they weren’t interested in Christianity or in being compliant with Christian principles. And so they really saw this being the linchpin of being able to erase and eradicate the Native American religion, was getting rid of peyote.

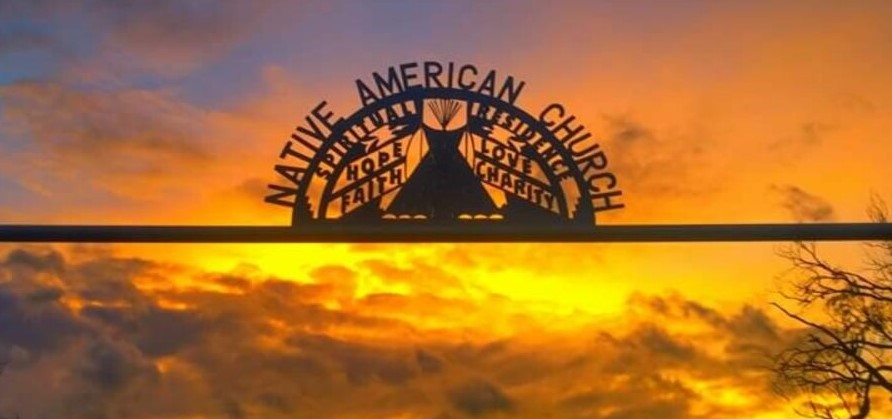

At this time, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Christian missionaries were working really hard to make this illegal, and we’re starting to see many areas of erasure going on. We’re seeing boarding schools, treaties being broken, kidnappings, targeted erasure of culture, religion, language. And in the late 1800s, a number of key players among the Native American tribes started to come together and realize that this wasn’t so much a game of trying to preserve their way of life or identity anymore. It was more of a way of preserving whatever they had left and that they were going to have to band together to make that happen. And if you’ve read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, she talks about the government tactic of dispersing Native Americans far and wide in order to be able to get them to assimilate and erase their culture. And so Native Americans saw that their only hope was to band together in this one thing. And even though up until then they had had widely different uses of peyote, some tribes didn’t even have exposure to peyote, they had different viewpoints on how a church should be run. But the general consensus was that the Great Spirit had given them this gift in peyote and was speaking to the Native Americans through peyote, and that they should move forward with preserving that even though not all tribes had used it previously. That was how they felt justified in using it due to the circumstances. And the first version of the Native American Church was formed in 1917. And it hasn’t been without a lot of work and some bumps and clarifications with the government along the way, all the way up until around 1993. But it has been in motion ever since 1917. And it was the Native Americans’ answer to the government erasing their religion while also simultaneously claiming that they preserved religious freedoms. So they said, why don’t we bind this church together and we will have some strength in numbers and then we can claim protection on their own terms?

AA: I was going to ask you about the Native American Church, because my understanding is that people who are not Native American and want to participate in ceremonies using indigenous plant medicine have to join the Native American Church in order to do so. Is that right?

AG: Yes, and it does vary a little bit by state. For a long time, it was only open to people who could present documentation or whatever that they had Native American ancestry or blood. But at this time in many states, you actually don’t even have to join the church in order to do a ceremony. In Utah you do, but it’s open to all at this point.

AA: I see. That’s interesting. And so they do have different rules and policies in different states.

AG: They do. And it’s just slightly different. And actually within the church there are some factions that have more of a Christian slant, and we’ll talk about the medicine wheel in a little bit, but the Native American origin stories and life view was very geared toward adaptation. So a lot of them adapted their rites or ceremonies to make space for a Christian slant to it. Whereas other groups, even underneath the Native American Church umbrella, felt that they wanted to have more of an earth medicine, earth religion slant. And so you see a little bit of variation across ceremonies in the church, as well as rules and regulations state to state.

AA: Got it. That makes sense. I’d love to talk about your experiences with peyote, both of you. And let’s start by having you talk about your own intentions and hopes for the ceremony. Going into it, what were you bringing?

AG: So, I have an ancestor who was Navajo and Paiute, who I had grown up hearing so many romanticized stories about. It was basically these white saviorism stories about how she was in dire need and they swooped in and saved her from a horrible situation. And I believed all those stories and grew up hearing them and teaching them to my own children even. But a few years ago I started feeling more interested in her life and some of the details of her life. Her father actually happened to be one of the last standing Navajo chiefs, and her mother was Kaibab Paiute. And it was very uncommon for people to get married across those two particular tribes. But they fell in love, got married, and had two children, and by all accounts, lived very happily and peacefully with the Kaibab Paiute tribe. And at some point her mother passed away when this ancestor was very young, and they had to move and migrate over to the Diné Navajo tribe where her father was the chief apparent.

And the recordings that we have, you know, there’s always a little bit of variation. But it sounds like the Navajo were not sure if they were going to accept her because she was half Paiute and a girl. So her father was kind of sitting with this, trying to figure out what to do about this, when some Mormon settlers and missionaries were coming through. And at the time, he had a favorable view of Mormons. That changed later on in his life, but at the time he did. And they said, “You know what? Why don’t you let us take your daughter and we will take good care of her? She will be like one of ours.” And so he decided to let them take her and she was probably around seven years old, although accounts differ a little bit. But she was very young and now she’s assimilating into Mormon culture. She is being given a new name. Her name became Sarah. She was expected to erase everything about her that belonged to her Native American ancestry and culture and lineage.

And she lived with them for a number of years, and we don’t know exactly but somewhere between the ages of 11 and 15, the Mormon Church was really wanting to – Mormon leaders, I should say – were wanting to improve their relationships with Native Americans. And so there was a very high-ranking Mormon leader who sent a messenger in the middle of the night to wake Sarah up and have her be married at that moment, in the middle of the night, to a polygamist Mormon man who was two to three times her age. And the accounts are that in the middle of the night, they woke her up and she said, “I guess I’ll marry him, but why does this have to happen now? Can I go back to sleep?” And they said, “No, this has to happen now.” So in the middle of the night, she is married to this man who is in his thirties, and she was the third wife. I believe one of the other wives had passed away. And she had four children, and I believe my ancestry comes through the second child. But she died somewhere around the age of 24 shortly after giving birth. The other wife did not want her buried with the other family members who had passed away because of her Native American lineage. And so they had her buried in an unmarked grave. Nobody knows where it’s at in a different cemetery.

As I learned these things, they were so different from the reality that I had learned when I was younger. And I felt very unsettled, like some sort of enormous emotional wound had opened up that I could not heal no matter what I did. I tried reading and learning more. I even did some breathwork and meditation exercises regarding ancestral healing, but I felt like I wanted to go deeper and I was not able to do that just with my own self. And I think really what I was experiencing was extreme disillusionment and grief at the same time. So it’s a very complex emotion. Separately, I happened to be reading a book a little while later on shamanism, and some of the roots of shamanism and different practices inside of shamanism. And at one part it talked about something called a soul retrieval, which is this idea that when you have been separated from a part of yourself due to trauma, or an experience, or even just trying to assimilate into some sort of situation which you may separate from a part of yourself and lose a part of your soul. And in Native American culture, they would often have a ceremony done by a medicine person who would link that part of your soul back to yourself. And I started wondering if a living ancestor could potentially go back and do a soul retrieval for a previous ancestor, which is kind of ironic that this was coming to my mind because at that point in time, I didn’t even know what my beliefs were. I was deconstructing a very high-demand religion, I don’t even know if I believe in a soul, but it really called to me. And so I felt like, “I’m just going to chase this.”

So I reached out to the Oklahoma Native American Church (ONAC), which is the Native American Church I talked about earlier. And a very helpful person gently informed me that it’s called “ancestral line clearing” if it’s somebody who’s living doing it on behalf of their ancestors, and that soul retrievals are really for your own person. They’re not for other people. But they very gently, very kindly informed me of this and then pointed me in the direction of a very skilled guide who happens to be in Utah and suggested peyote as part of the ceremony as a powerful tool for healing for this particular instance. I also did have a personal desire for the grandfather medicine to help introduce me to my authentic core self, like I talked about, and feeling those tendrils and what my personal unique energetic stamp is. But my main purpose was for ancestral line clearing. And I really hadn’t ever expected to sit with peyote. Like BreAnna mentioned, it’s endangered, it seemed like something that should be left for the people in that lineage. And I have great cultural respect for the medicine as well as the Native American Church itself. But after reaching out to ONAC and finding out that they felt like that was probably the most beneficial route, and finding a medicine woman who had so much experience, I felt like I could pursue this option with integrity.

a personal desire for the grandfather medicine to help introduce me to my authentic core self

AA: That’s something that I’m always thinking about too, and I know the three of us have talked about having that respect and not ever wanting to commit cultural appropriation or participate in something that then accidentally causes harm. And so that’s a beautiful and really important part of the story. I think it’s so lovely that she was able to invite you right as a medicine woman herself to say, “Yes, please do this, and we’ll invite you onto this path.” That’s really lovely. Bre, what about you? What were you bringing to your experience with peyote?

BL: As Alicia had said, she had been invited to do this ceremony with the ONAC church. Peyote is not something that you do individually, it’s done in a group. And because of the individual nature of Alicia’s desire to do an ancestral line clearing, it felt right to have that be done with people that she knew, so the energy in the teepee would be very stable. And so she extended an invitation to me to join her in this ceremony. I had been interested in doing some work with peyote because through the course of my female empowerment and doing a lot of work with the divine feminine through Mary Magdalene and other groups, I had realized how out of balance my understanding and even my willingness to engage with masculinity was.

And as I had done more healing work and could see that although it is a pendulum and coming out of a very male-gazed religion, I swung back out. But as I became so strongly into the feminine empowerment that I was disconnecting myself in some ways from my husband and that I also needed to do some work with my own balance and understanding of masculinity because I do have three sons and so I can’t just exile them and be like “men are the problem” because I want to be close to them. And my whole path started with me not wanting to be spiritually amputated from my children and my husband. And so I came into this realization that I’ve got the divine feminine working here strongly, but the masculine is something I don’t even want to work with. I don’t want to acknowledge it.

And so I was interested in working with peyote as we’ve talked about, known as a masculine energy and the Grandfather, to help me understand that and to bring down some of my walls and my defenses that I had built over many years of masculinity that I had seen as just totally unworthy of the power that it takes, and that is harming everybody. And my one intention was working with some of that balance of masculinity to bring myself back into balance and to bring myself into balance within my household and in my connection with my husband and children and also myself. And then also after COVID, I had been doing some therapy work and came to the realization that I had been functioning with anxiety for a large portion of my life that I had cloaked as introversion very subconsciously. Because I felt like it was more socially acceptable if I just claimed all of my “I can’t handle this” as introversion rather than anxiety. It also kind of gave me a permission slip to not deal with it because it’s fine to be an introvert and it’s fine to be an extrovert. And so it let me shelve this idea that there are just things that I cannot handle and deal with.

Peyote specifically has been tested recently in trials for anxiety and has had really promising results, where 80 percent of the participants will come out of the clinical trials having marked reduction in their anxiety and their ability to function with that. So as I was connecting this idea that I thought I was an introvert but it’s actually anxiety and now I need to understand that anxiety, understand where it came from, understand where it stemmed from, and then do some work releasing that, peyote came into the picture as a really powerful plant medicine to do work with anxiety. So those were my two main intentions going in, was some balance with masculinity and then doing further work to heal and release the anxiety that I’d been carrying.

AA: I know we talked a little bit as you two were preparing to go into the ceremony, that Bre, you were talking about your feelings as it was getting closer that you were starting to have some worries especially about your encounter with the masculine. I’m wondering if you could talk about some of the things you were nervous about.

BL: Definitely. I am a very systematic person and I use checklists as a way to validate myself and find myself worthy. And that is not how plant medicines work. So as I was coming into my preparation to work with peyote, I checked off all of these lists of the things that they tell you that you can do to help you prepare for the ceremony. But as I came in closer, I had this sideline gaze that was, “you are going to have to sit and surrender to a masculine energy.” And you are not open to that at this point. And that started asking for some attention there. And anytime you’re going to surrender your psyche, it’s going to be terrifying. Your ego is going to try and resist. And all of these systems and programs that we have in place that keep us safe and keep us functioning are going to push back against that. So I knew that in that experience, if I was not able to surrender and let go of that psyche resistance, that I would not be allowing the peyote to work with me in the way that I wanted it to. So as I was trying to figure out how I could feel more comfortable sitting with a masculine energy. In our conversation, you gave me the great advice to try and find a male elder that I would feel like I wanted to sit around a fire with and receive information from. And as I thought about that, I realized that most of my experience with masculine leadership has been so underlined with me feeling that that leadership and wisdom and knowledge is not founded in anything other than your gender that I had a really hard time, even with people I genuinely love like my father and my grandfather, where I felt like I don’t necessarily want to receive the wisdom that they would give me because I’m going in a different direction. And I want to go to a place that they have not been in this balance of masculine and feminine devoid of patriarchy. So I felt like that’s not the person I’m looking for. This is not the person I was looking for.

And I had to search all the way down to this one podcast I had listened to many, many years ago about a Mennonite priest. The podcast episode is about a Mennonite preacher who has a son who comes out as gay. And in the process of that, he starts to reject the teachings of the Mennonite church and follows his son. And the end of the arc is that his son finds somebody that he loves and that he wants to marry and this Mennonite preacher wants to perform that marriage. And in order to do that he knows that he will be stripped of all of his powers within the Mennonite church. And so he wrote a letter called ‘An Open Letter to My Beloved Church’ and talks about how could he be asked to reject his son and he doesn’t need any power here any longer because he’s done the thing that means the most to him, which was officiating the wedding of his son. And that kind of love and self-sacrifice was not something that I had ever witnessed, where any male leadership would sacrifice on my behalf in such a personal way and I hadn’t even heard stories about that.

And so I had gone in using that, that this is a man who I would love to have as my grandfather energy and sit with me. And so through that experience, I realized that the energy that I had come in with, of masculinity being power hungry, controlling, and very minimizing to women. And the idea that I would need to submit to that and surrender to that was really unsettling to me. So that was one of the most toggling things for me, was this idea that I knew I did need to surrender to it and that whatever was on the other side of that was going to give me healing and growth. But because of my history in a high demand patriarchal religion, that was very unnatural for me and I did not have a clear path of how to sit with that energy being the teacher with having a lot of fear deeply rooted in the masculine taking over.

I knew I did need to surrender to it and that whatever was on the other side of that was going to give me healing and growth.

AA: I think a lot of listeners are going to resonate with that, and I’m really grateful that you shared how you were feeling going in. I cannot wait to hear how it went once you got there. Hopefully it was a good experience, and I want to know how. Before we get there though, Alicia, what were some of the fears or worries that you were carrying?

AG: When Bre and I were talking about answering these questions, it’s interesting because we both had very, very similar fears coming up as we were going into this. Not knowing how to let your psyche be safe in that form of surrender, not in a meeting of minds kind of way, not in an interacting with masculine energy kind of way, but in a full surrender sort of way. It is pretty intense when all of your experiences have led you to protect and armor up at some point, and when you’re going to just lay your psyche bare and be completely in a surrendered state, that’s unnerving. The other fear that we were both staring down pretty hard going into this ceremony is that when you look into peyote ceremonies, they all pretty universally will tell you to be prepared for “getting well” which is what they call in ceremony vomiting into the fire. And to be prepared for that to happen for the first two hours on repeat. There are so many levels to that. I’m someone, and I know Bre is as well, who has spent a lot of time being sick. When I was pregnant, and I get chronic migraines, I have something called Meniere’s disease, so the idea of voluntarily sitting and being sick or “getting well” was pretty intense and preparing to surrender to that possibility was very daunting.

Baked into that description of “getting well” is the idea that you have to allow whatever is coming up to flow in order to heal. And like Bre talked about earlier, with peyote the way that it grows, also being somewhat linked to its signature, it is rather bitter. And that bitterness, as it goes down, is the medicine that you have to trust and relax and surrender into to allow it and trust that whatever it is bringing up that might be bitter is going to be what you need to get to the other side of wellness. So if you want to get well, you have to cross that wall of fear and find out what’s on the other side. We prepared a lot for this ceremony to be able to surrender to the somatic element of this. Some of the things we did were getting used to discomfort. A lot of people will say, “What if it makes me feel uncomfortable?” It’s absolutely hilarious, because of course it will make you uncomfortable. And we had read a lot about that, so we put ourselves in a lot of uncomfortable positions. We did cold plunging regularly. We did some fasting that doesn’t look quite like religious fasting, but is fasting. Wim Hof breathwork that switches the balance of carbon dioxide and oxygen in your body to be able to sit with that discomfort. Even taking high doses of vitamin B3 which gives your body a very somatic response. If anybody’s ever tried that, you know it’s sort of a flushing hot experience that you just have to sit through and you just have to let it be until it passes. But it is actually flooding your body with nutrients and oxygen and vitamins and blood and all that.

So we really tried to lean into meeting ourselves in those spaces and sitting with the duality of discomfort along with healing, and to learn to allow the medicine to do its work without resisting it so that we could surrender to whatever the medicine brought up. And with our peyote experience, there are different styles of dosing and that sort of thing. But the experience of the peyote came on quite gently, even if it made us uncomfortable. And so if you weren’t used to being able to sit with that discomfort, it could be really easy to resist it and not allow it to do its work and run its full course.

AA: Well, that brings us to kind of a cliffhanger of an ending. I know I’m dying to hear how the ceremony actually went, but in the interest of time, we’ll wrap up now. And then in part two, we’ll have you tell us all about what it was actually like to sit with Grandfather Peyote and surrender to this masculine plant medicine. In the meantime, thank you so much for being here, Alicia Galbraith and BreAnna Larson.

BL: Thanks for having us, Amy.

AG: Thank you so much.

you are going to have to sit

and surrender

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!