“a better world for women is a better world for everyone“

On today’s episode we visit the number one country in the world when it comes to gender equity—Iceland—to take a closer, more critical look at the history and present day lives of women in a nation viewed as the gold standard for women’s rights. To help facilitate this exploration of Icelandic culture, I’m thrilled to say that today we’re joined by globetrotter Rachel Greenley, as well as a number of Icelandic locals who generously sat down with Rachel to discuss to discuss patriarchy overseas, what American and Icelandic feminism can learn from one another, the red stocking movement, and the incredible history of how Iceland has become a world leader in gender equality.

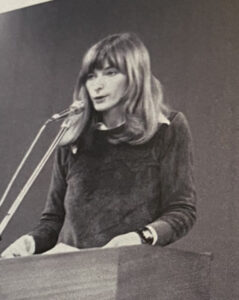

Our Guest

Rachel Greenley

Rachel Greenley (she/her) has a master’s degree in International Development and is passionate about women’s empowerment. She travels, lives, and works around the world with her husband and children.

Hello. My name is Rachel Greenley and I currently live in Reykjavik, Iceland.

I am so happy to be a part of this project. I have loved this podcast and listened to every single episode. I think we can all agree that Amy has approached this project with such balance, compassion, humility, and frankly intellectual stamina. When I think about the amount of texts she has covered in a year’s time with quality analysis I am in awe, so thank you so much Amy for sharing this journey with us. I have learned so much and I think it has really set a good foundation for all of us to understand the history and the manifestations of patriarchy in our lives so that we can move forward and know how to dismantle the parts of our inherited system that just aren’t working anymore, so that we can move towards egalitarianism and a society where all can thrive. I particularly love the episode regarding Anne-Marie Slaughter’s book Unfinished Business. If you haven’t listened to that episode, I suggest you go back and listen to it because I mention her article and book here.

So 10 years ago I was single, 27, and living in Washington DC when Anne-Marie Slaughter’s Why Women Still Can’t Have It All came out. As a quick recap, Slaughter discusses her decision to leave her dream position at the state department under Secretary Clinton as a political appointee so that she can return to Princeton and her professorship to be more present for her teenage children who were struggling and needed more parental attention. She argued that, despite many advances in the Women’s Movement, there are still many women who can’t have a career and a family in a truly balanced way. And then, soon after, Sheryl Sandberg (the COO of Facebook) came out with well-known book, Lean In, and this encouraged women to retake up the feminist cause to shatter the glass ceiling by leaning into their leadership track jobs, climbing the corporate ladder so that they could be in decision-making positions to make real change happen. Both arguments resonated with me and clearly stated the important needs for breaking down patriarchy.

On one hand, I could see the need for female representation in leadership positions to create space for structural change. On the other hand, I also saw the need for quality care of the elderly, those with special needs, and children—and that kind of quality care was not and is not available in a way that is affordable or accessible in the United States.

So, as we well know, it is often the women who have to leave the work force and provide that care for their family, which in many cases can be financially devastating to families. In the years that have passed, I have come to see that these two needs need to be filled simultaneously. We can’t wait for women to rise to the top of government and private sector companies to make the changes that we need. We need to enable caregivers to have the resources to develop their professional skills and stay employed while also ensuring that those who need care in their lives are provided for with quality care.

Both Slaughter and Sandberg agree that the next phase of the Women’s Movement needs to be a Man’s Movement with components of elevating the reputation and value of caregiving which patriarchy dramatically undervalues. While traditional ideas of what women’s roles are and what they are capable of have changed rapidly, they have not changed as rapidly for men. While our boys ideas of masculinity are still slowly changing, their understanding of their role as the sole breadwinner of their family has not. If we can help encourage everyone to pursue a career while prioritizing the care of family, we could be well on our way to breaking down patriarchy and replacing it with true valid egalitarianism.

When I met my husband, I was 28 and in grad school, studying International Development at George Washington University in Washington DC. He was a Foreign Service Officer (or a diplomat) and that meant that we were going to live around the world together. I was very excited and eager to start this adventure together, and I naively thought that I could easily build a career in my field because it was international and I could take it along with me as we moved around every two to three years. Since then, two wonderful children have joined our family, and while I was able to find work with the USA contract when we lived in Tunisia for a year-and-a-half, the career I had envisioned was not so clear-cut.

Now, through some turbulence but much good fortune, we have landed in Reykjavik for the next three years. Not only has this been the best possible place to wait out the world pandemic, but it has also become the place where I’ve been transported to the world that I had hoped for 10 years earlier when readings Sandberg and Slaughter’s words. In my small community in the suburbs of Reykjavik, I can see how a simultaneous change in culture and government policy has brought balance to work and family life. For 12 years running Iceland has been ranked number one in the Gender Gap Report; this report is annually released by the World Economic Forum and it assesses a country’s level of egalitarianism based on comparing women to men with metrics such as economic participation, education attainment, political empowerment, and health and survival.

With this long reign as the leading country in egalitarianism, Iceland has been able to push the envelope on breaking socially-constructed gender norms, and has altered the cultural psyche of what it is to be a fully participating member of society. The Icelandic government offers an extensive list of family-friendly policies that have contributed to breaking down patriarchy. I can’t go over all of them because they are many, but some of them that I find prevalent to our conversation and some that might be more attainable for the United States are: parental leave for both the men and the women recently changed from 9 months to 12 months of parental leave, divided between the spouses (so six months for the woman and six months for the man). This means that if a family with two parents wants a full year of paternity leave, each parent has to take their six months. That means the mother will have six months as the lead parent at home and the father will have six months as the lead parent at home—I think that in and of itself has the potential to make dramatic changes in how the world and men understand the importance of early childhood care and all that goes into it.

Another government policy that is huge is that there are childcare and education subsidies making it affordable for parents to put their children into preschool. There are also generous leave policies of 10 sick days for adults, but an additional 12 days to care for sick children under the age of 13, and a minimum of 24 days of vacation. There also was an equal pay law passed in 2018, and the government offers guaranteed child support from the government after a divorce if the ex-spouse cannot pay support. And last but not least, some of you may have seen in the news recently that the government has partially implemented a 36-hour work week. I have a friend that I’ve gotten to know through preschool—our children are in the same preschool together—and she works for the government as a lawyer. She said that the new 36-hour work week has been amazing in helping her have more quality time with her children. She’s able to be there in the morning, help them get off to school without any rush or stress, and then she’s also able to be there when they come home.

I know that these all sound lovely and I’m sure everybody would want to have such wonderful policies, and to answer the question that I’m sure many of you were asking—how was this all paid for—to be honest it does come with a high price tag. Iceland pays for all of their family-friendly benefits (which also includes socialized medicine) with a 46% personal income tax. That’s nearly half of their personal income being taxed. There’s also a 20% corporate tax, 20% capital gains tax, a 24% sales or value-added tax, and there is no military to speak of so military spending is almost zero. The national deficit is only at 16 million US Dollars, so a lot of these taxes then go straight to this substantial safety net. All of this makes Reykjavik one of the more expensive capital cities to live in. I can tell you it is painful to take three sweaters to the dry cleaner and have a bill of $90, and it’s also hard when I’ve compared prices when a toy in the toy store will cost $45 and it will cost $20 on Amazon. You do feel that price. I know that we come from a position of privilege, but I will say that when I do feel that pain of paying that extra high price I think about the investment that is being made in my children and the quality school that they have. I am willing to pay for my position when I need to and I understand that that might not be the case for a lot of Icelanders who might not have the same privileges as us.

I wanted to move on and kind of look at how Iceland got to where it is now, and I want to interview Guðrún Ágústsdóttir. She is a very impressive woman who I’ve loved getting to know—she was a leader in the Red Stocking movement of the 1970s and later pursued a political career where she was the president of the city council of Reykjavik and later worked with a shelter for victims of domestic violence. So without further ado here is my interview with her.

Rachel Greenley: Guðrún Ágústsdóttir and I have gotten to know each other from a book group that I was fortunate to join when I arrived here in Iceland. It has been lovely getting to know all of the women in this group; they have a diverse understanding of Iceland and when I mentioned to Guðrún, I think my first book group experience, that I was currently doing a deep dive into American feminism, she brought out a book of Icelandic feminism. And she showed me the chapter on what was called the Red Stocking Movement and how it influenced the women’s movement in Iceland. I’ve since then been very interested in it, and it is an important part of Iceland’s history that helped us understand how Iceland is where it is at the top of the Gender Gap Report.

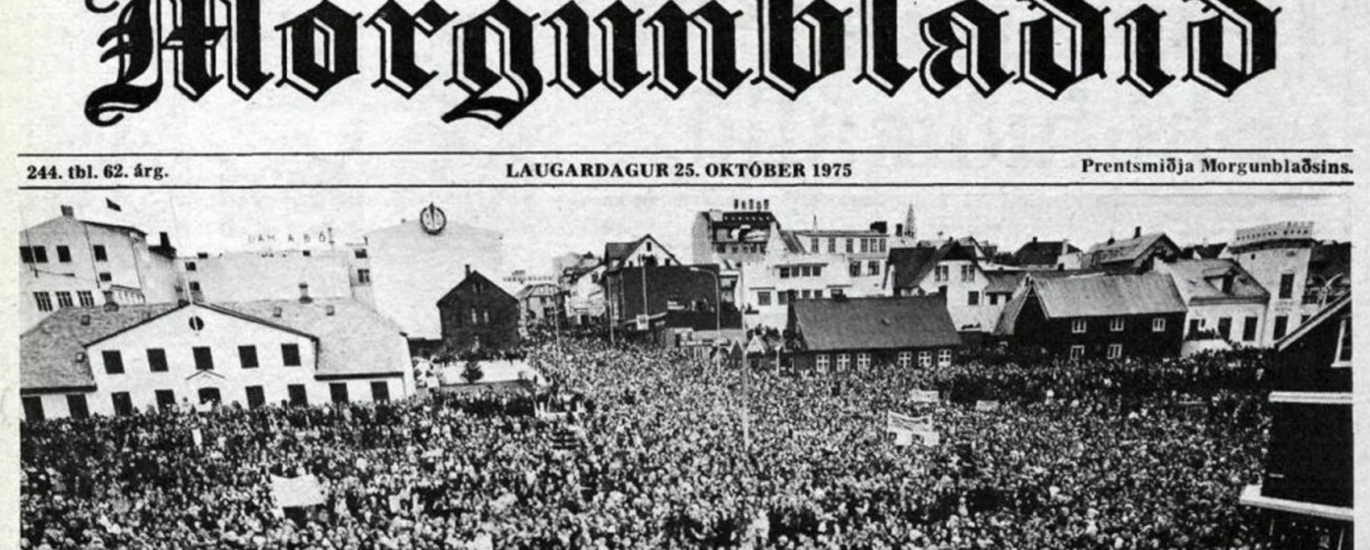

Guðrún, I wanted to first start off with some of the basics of the Red Stocking Movement so maybe you could start with explaining what happened on October 25th, 1975?

Guðrún Ágústsdóttir: Well by then we had been working together for five years and we sort of thought “we have to do something very big in order to change the life of women in Iceland for the better.” And chasing the light for women in Iceland for the better means a better life for everyone. We had been focusing on so many things—abortion rights and women’s equality in the workforce (which was far from okay) —and in order to allow women to have equality in the workforce and education then you needed to have care for your children. So these and other things were our main subjects, and then somebody came up with the idea “why don’t we just go on a strike? Take a day or half a day on a strike?” and then somebody mentioned that the United Nations had a Women’s Day and a Women’s Year that would start on the 24th of October 1975. We all said ‘yes!” so we started in January 1975 with a big conference with the women that were in the trade unions for the lowest paid women (we arranged this, The Red Stocking) and then I was chosen, because I was in one of the trade unions, to come forward with this idea and the women said “yes, we will be with you.”

At the end of this conference that took a whole day, they all agreed that they’d be working with and promoting this idea to do the strike. There was a committee that worked on it until the day—very efficient women—and in June we had a big conference with all women from the political parties and from all the trade unions and whatever. When we were coming to the close of this meeting we were doing all kinds of things, then this idea of going on a strike came up for vote and the conservative women said “we don’t like this word strike.” So that was a clash, you know, and then one elderly woman said “why don’t we just call it a day off?” and we went on with it. It ended with 90% of women in Iceland taking part, all over the country…

RG: That’s amazing. 90% of the women in the entire country walked out of their jobs, of their homes, leaving men to take care of the children and to fend for themselves in the workplace. 90% were out protesting.

GA: Yeah. We were protesting because when we were asking for equal wages and things like that, the men would say “your work is not important. You’re working because you want to have a better life. You want to buy clothes and travel and things like that, but it’s not as important as the work of the men.” Everything, of course, broke down in Iceland so after that nobody ever tried to say that the women didn’t matter. That was a great success, and it gave us power to go on, and then we became world famous! And I think this, you know, made it less difficult for us to vote for Vigdís, the first female president democratically elected in the world in 1980. That was very important for women in Iceland; we all love her and are very proud of her. We have a woman Prime Minister and we have a woman Minister of Health.

RG: That’s great. Some of the original demands, from my research that I saw, of the Red Stocking Movement were to help women succeed in the workforce and to gain more equality, and part of that crucially was childcare. That was part of the initial demands of the Red Stocking Movement, correct?

GA: Absolutely. We said that there should be preschools, free of charge, for all children, and we had to wait for a long time for that to happen, but it was important and there was passed a law in 1990. This would be the first time preschool would be called school, part of the educational system even though the child was only one or two years old. What we did back in the Red Stocking Days was we started out with kindergartens, so we would hire somebody (we had to pay quite a lot ourselves) and we worked in the kindergarten ourselves until several Red Stockings took over the Reykjavik City Council in 1994. The mayor was a former Red Stocking and I was the President of the City Council and one was taking care of very important things also—so three Red Stockings and that’s when it changed dramatically in Reykjavik (which is, of course, the capital).

RG: Which goes to prove the fact that female representation is how structural change can really take place and how it has happened in Iceland.

GA: Yeah, it helps that the women are open minded and then they can change the world.

one elderly woman said “why don’t we just call it a day off?” and we went on with it. It ended with 90% of women in Iceland taking part, all over the country

RG: And so all of these changes in government policy—and I know in the recent election it was almost parody in parliament, not quite but almost. You’re still very close to having equal representation in parliament—and so how do you feel and how have you seen in your lifetime the change of how this has affected women’s roles in society and even men’s roles in society?

GA: Dramatically. Iceland is so different from when I was a young mother, you know, starting my first steps in the feminist movement. There was one woman in parliament in 1970, and two or three in the city council in Reykjavik and very few women went to university. Now there are more women taking higher education than men, and the kindergarten children, and the right to maternity leave (now we call it maternity and paternity leave because both men and women have to take their part of this paternity leave and that means they connect to the children in a different way). We’ve seen that it’s so good for the men to get so close to the children.

One thing that I am very pleased with recently is that now people can decide their own gender. They don’t have to be either man or woman, they can change what they want to be and it’s their decision to make. That was passed only one year ago or so, that law.

RG: Thank you. One final question is with all of these changes—and I’m that you brought up that we still have progress that we need to make—but I’m sure that you have had to deal with a lot of critics and a lot of people questioning, you know, ‘if you give women this right, society will fall apart because no one will take care of the children’….Do you feel that the strikes that you have witnessed in the history of Iceland in your lifetime, have they improved not only the woman’s quality of life but also everyone’s?

GA: Yes, obviously. Children have a much better life. The school system is so much better than it was. And some of them don’t know it yet, but they all have support from women. It’s famous that women give quite a lot of love to their surroundings, so do men but they have to learn. I think that, as I said before, fathers and children have the possibility for much closer relationships and to be able to educate yourselves as you wish, and the health system and healthcare in Iceland and all of this…It’s a much better world for everyone. We have always said ‘a better world for women is a better world for everyone.’

RG: Exactly. You truly are a world leader and we’re so grateful that you are showing us an example of what is possible, and we’re deeply grateful for all of you who really pushed hard in the Red Stocking Movement to give the world an example to look at. Thank you.

GA: Thank you.

Now that we have looked at the history of Iceland and how the country has gotten to be where it is today, I wanted to give a concrete example of what it looks like on the ground. Palina is a kindergarten teacher and her partner, Birkir, is in sales, distribution, and merchandising for the biggest bread company in Iceland. They have a 3-year-old daughter and just welcomed their new son in July. With the arrival of the newest member of their family both Palina and Birkir were able to, between the two of them, take up to 12 months of paternity leave.

Palina is currently pursuing a teaching certification at the university and tells me that she wouldn’t be able to do it all without the support of her partner at home. They work equally at home and feel that they have a true partnership in dividing household chores. Once the parental leave is up, both parents will have to return to work. When their son is 12 months of age, he can go to the leikskola, which serves as a hybrid day care and kindergarten for children 12 months to six years of age. Palina and Birkir’s children will be able to attend this school from 8am until 4pm, five days a week. They’ll get two healthy meals and a snack will be provided. Each classroom has around 20 children with one lead teacher and up to four aides. That is a ratio of five children to one adult (which is beautiful). The lead teachers are highly educated, with a masters degree in early childhood development. They implement play-based learning that is so characteristic of Nordic and Scandinavian countries both indoors and out (no matter the weather). This quality of care would be of extreme cost to any family in the United States. I know I have recently read that in Washington DC the cost of childcare is around $2,500 a month. However, in Iceland the government subsidizes early childhood care and education. So Palina and Birkir will at most pay $500 a month for both of their children to attend a leikskola. Parents can have great peace as they send their children to a place where their health, education, and wellbeing will be safeguarded.

To get more insight, I have interviewed both Palina and Birkir about their experiences. And as you listen to them talk about their experiences, I think you can see how the changes in Iceland have really taken huge steps in breaking down patriarchy: gender norms within the home, how we raise children, how childcare is dealt with in the patriarchal way is much different in Iceland than in the United States, for example. Please give a listen and enjoy their interviews….

Rachel Greenley: Hello, Palina!

Palina: Hello.

RG: Thank you for joining us on this. I know Palina through our children who are at the same preschool and our daughters have become the best of friends.

P: Oh yes!

RG: We have spent lots of time together getting to know each other, and I’ve been able to see firsthand how wonderful the Icelandic system is for families. So Palina, I have really appreciated that you guys have let us into your lives and that we’ve been able to really see how Icelandic culture is at its best. I just wanted to go ahead and ask you about some of your experiences of being a woman here in Iceland. How would you say that your life as a woman is different than your grandmother’s?

P: My grandmother was born in 1935. She didn’t have any opportunity to educate herself because he was a stay-at-home mom. And I think that’s the reason why she never worked or went to school, because she was staying home as a mom.

RG: How many children did she have?

P: Six. Yeah, and with each child she only had 3 months paid maternity leave, but for me I am getting my education. I have so many opportunities to make a name for myself and just do whatever I want even though I have two children, and I get to stay home with my children for 10 months now.

RG: You said the gender roles your grandmother was kind of put into more rigidly…do you feel like you’re as bound to those nowadays as she was back then?

P: She did everything in her home. My grandfather always worked outside, and I don’t think he was a big part of the upbringing.

RG: Your grandfather was not as involved in the child rearing as it is today?

P: No no no. We are so equal, me and my husband. It’s just divided 50-50. Everything in the home and then the children’s lives… I couldn’t do it if I didn’t have him. It’s so hard, as you know.

RG: Agreed, we both have wonderful husbands that are very heavily involved with our children’s’ lives and help take care of them. My next question is how has the maternity and paternity policies in Iceland affected your family?

P: Well, we get to spend more time together at home, me at first with the little one and he after a few months, but the payment could be higher. It is 80% of my salary, divided…

RG: Every month you’re getting paid your salary at 80%, not your full wage?

P: Yeah. You know, especially when you work at a place where the salary isn’t very high (like me) then you feel the difference in 80% and 100%, but our child gets to grow in a safe and secure environment and I get to enjoy it, and we get to know each other and I don’t have to send him away at three months.

RG: From what I understand Birkir has not yet taken time off, he’s not taken his paternity leave?

P: No, he took a summer vacation the first month our baby was born because it just happened that he was born in July and, you know, Icelanders take their summer vacation June, July, or August. So in May he will stay home until October and then I will go to work.

RG: How was having Birkir home for that first month, and how did it affect your family?

P: It was amazing. Our older daughter was home for summer vacation from school so if Birkir had been working it would have been really hard to have both the children at home because my baby was having stomach issues. Our daughter was three and a half years old and she always has to have something to do and someone to play with, so he was always taking her outside or stayed home with the baby and I went outside with her. We decided to split it up like that.

RG: So it was probably pretty crucial?

P: Yeah, but when our daughter was born he was also home for a month and it was just amazing. We both had the opportunity to get to know that baby, and the baby got to know her mom and her dad (not just a mom).

RG: Yeah, and that bonding is so important, especially at the beginning.

P: Yeah, and with the hormones and birth and everything, you are just sensitive, so it’s good to have the support of your husband or mate or whatever.

We are so equal, me and my husband. It’s just divided 50-50, everything in the home.

RG: That’s lovely. So now about your son, and how Iceland has shifted how gender roles are in society—I’m curious, what do you envision for your son’s life? And what do you hope for him in his future? And how is that going to affect your parenting?

P: Well now it’s so amazing to see that the young children today (or pre-teens or teenagers); they have such an amazing view on life and people. They are so aware that you can just be what you want to be, and it doesn’t matter if you’re Black or if you’re a woman or a man or gay …it just doesn’t matter. You just get to be. And that’s amazing and it wasn’t like that.

So we will raise him with gender equality in mind and that people are different and it is okay. With that he can have the strength and self-esteem to be whatever he wants to be.

RG: That’s lovely to be in a situation where you are accepted for who you are.

P: Yeah, and it opens society. I just can’t imagine how it was a few years back.

RG: And it’s changed very rapidly.

P: Yeah.

RG: Thank you for that and thank you so much for taking time out of your day to share your insights and experience. We all have so much to learn from Iceland and we are grateful for you.

Rachel Greenley: Hello Birkir, thank you for being here.

Birkir: Hello.

RG: This is Birkir, he is Palina’s husband (who we just talked to) and just like Palina, we have really enjoyed getting to know you and your family. Birkir has cooked for us many times, he makes wonderful pizza and amazing hamburgers and he is just fun to be around so I’m really looking forward to this conversation.

I wanted to start and ask you about the changes that you may have seen in your lifetime and through your family. How has the role of men changed in your home over the last couple of generations?

B: I mean I can only talk about it from my perspective. I just remember my father working and basically my mom also working, but also taking care of the household. They had different…my dad took care of the cars and stuff like that, but indoors and meals and stuff like that my mom took care of, but nowadays…

RG: Were they more pigeonholed into what would be traditional gender roles within the home?

B: Yeah, traditional gender roles.

RG: Would you say your grandfather or your father, were they very much involved with child rearing?

B: No, I wouldn’t say so.

RG: How does it look now for you?

B: Basically for Palina and I it’s 50/50. We both work, we both take care of children and have similar focuses about upbringing. We both parent our children. It’s not like I’m doing more than her or she’s doing more than me; it’s basically equal. I mean, when we, for example, clean the house we both have our things that we do. We have a system about it, but we do equally as much.

RG: That’s wonderful. How would you say that system helps your family?

B: It definitely benefits the children to have both parents parenting them. It shouldn’t be just one of the parents taking care of everything. Marriage isn’t a one-way deal. It’s both people chipping in. Sometimes she does more than me and sometimes I do more than her.

RG: It depends on the week?

B: Yeah, even just on the day—how you’re feeling, you’re not always up to doing everything you’re supposed to do.

RG: Do you feel like you benefit from this more open way of approaching gender roles within the home?

B: Definitely. I feel more connected to my children than I felt as a child to my father. When our daughter is having trouble with something, she comes to me equally as much as she goes to her mother. It’s much more satisfying to be a part of your children’s life than not being.

RG: Yeah, because there is so much joy in rearing children, but you do have to be present to be able to experience the joyful part. That’s wonderful that you live in a time when you get to partake in that.

B: I’m very grateful to have this opportunity to be able to take this much a part in the upbringing of my children.

RG: I think it sounds like a situation where everybody wins. You win, your wife wins, your children win.

B: If everybody wins then society wins in putting out better people who are better prepared for life.

RG: I couldn’t agree more. So in Iceland they give men six months of paternity leave when a new child is born—are you going to be taking your paternity leave, and how do you envision that going?

It definitely benefits the children to have both parents parenting them. It shouldn’t be just one of the parents taking care of everything. Marriage isn’t a one-way deal.

B: I will be taking 5 months next year, from the start of May to the end of September. But that means I will not be taking my summer vacation days during that time, so I will have 24 working days off (extra to the five months).

RG: And during that time you will be the lead parent?

B: Yeah. I also, with our three-year-old—we only had about nine months then in maternity leave—but I took three months then and it was great. It’s basically you’re taking care of your child and the house and I mean, who doesn’t know how to vacuum?

RG: And you get that extra time to bond with your baby. I think in that early time the opportunity to bond with the baby starts your relationship off in the best way possible.

B: Yeah.

RG: That’s so wonderful. In the United States I have heard anecdotally that men can be sometimes offered paternity leave, but if they actually take it they won’t be in good standing in their company. Is that the case here or is it pretty accepted that all men, if they have a new baby in their family, will take their paternity?

B: It’s accepted, yes. No problem taking your paternity leave. The law is if you were going to take everything that you have they can’t deny you.

RG: So you’re guaranteed to have your job back when you return and they’re not allowed to discriminate against you for taking the leave? You won’t be passed up for a promotion or anything like that?

B: Yeah.

RG: I think that’s all I have for you Birkir, so thank you so much for taking the time to share your experience with us.

B: Thank you, Rachel.

One of the true signs that patriarchy is being broken down in Iceland is not only are the families benefiting from structural change, but so are the teachers of young children. From what I have seen, teachers at the leikskola are respected and valued members of the community. From my research, lead leikskola teachers can earn between $48,000 and $59,000 with a chance at getting an annual bonus. In comparison, the average wage for childcare workers in the United States is around $25,000, which is less after taxes. While if you do take into account that, with a 46% income tax rate the wages of Icelandic teachers are a bit closer to the wages of teachers in the United States, the teachers of Iceland still have access to universal healthcare, substantial leave and other benefits that hold great value and increase their standard of living to be better than that of their counterparts in the United States.

I have enjoyed getting to know the lead teacher of my five-year-old son’s class, Unnar. She is wonderful and my son absolutely adores her. You can tell that she loves her job and that she’s very effective at it. She’s been teaching at the school for 15 years and it’s not uncommon for people to stay at their schools for this long; turnover is not very high, which I’m sure it is a bit higher in the United States. Unnar talks about how she still comes across many of the students that have passed through her classroom while she’s out and about, and this reinforces the community that is really strong in each little neighborhood.

lead leikskola teachers can earn between $48,000 and $59,000 with a chance at getting an annual bonus. In comparison, the average wage for childcare workers in the United States is around $25,000

When asked about her role in society, Unnar feels that she has contributed a great deal in raising the next generation of Icelanders and that her role in society is significant. And I agree. I’m so grateful to her and all at the leikskola that my children attend. They really have created such a warm and welcoming place for my children to go.

My poor kids showed up not knowing a lick of Icelandic; here it is mandated that all preschools be taught in Icelandic in order to protect and maintain the language. Within six months my children were almost fluent and had truly bonded with their teachers and classmates. We just came back from a three-week vacation in the United States and they could not wait to get back to school, to see their teachers and their friends. And as a mother I can’t express how happy I am to see that my children are thriving in this lovely school system.

Now I have gushed a lot about Iceland, and you can tell that I’m a bit biased on how well I think things work here, however, I do want to just highlight some of the things that Icelanders have mentioned to me that they still feel like they need to work on.

First, Palina who was interviewed earlier and is also a school teacher, says that she feels that other working parents only view preschool as a daycare and that they do not fully recognize or value the quality of education their children are getting. While they are playing, it’s very intentional play-based learning. Also, because it is a homogeneous population that is smaller, inclusion is not a strong point and there are things that can be done to be more inclusive to foreigners who arrive.

Personally, my experience has been wonderful, but I have heard anecdotally that there are other things that could be improved. And ultimately while Iceland is still at the top of the Gender Gap Report there still is a gender gap that needs to be closed. Equal pay is still not quite there and other areas could be improved.

Finally, the government is very open about the fact that, despite the high representation of women in the government and high economic participation in the workforce, gender-based violence is still very prevalent and that is something that everybody is aware of and that the government is continually seeking solutions to.

So in conclusion, like Sheryl Sandberg and Anne-Marie Slaughter, I see the dire need for both female representation and the need to elevate the importance of care in order to break down patriarchy. I have deeply appreciated this opportunity to learn from Iceland and how both can be accomplished. It is a wonderful place, and because of its small homogeneous population and unique history it has proved to be a perfect laboratory of what communities can look like if they implement egalitarian policies and support it with cultural evolution for gender roles. They have already completed a large part of the pictures Slaughter and Sandberg paint in their books for a better America.

I know that the United States is dramatically different than Iceland—with a comparatively enormous population and immense diversity ethnically, economically, and politically—it’s most likely that we won’t be able to replicate the Icelandic system. But I think it has been so educational to see how a society can look if it does implement policies that truly prioritize families and children. I think in general we can all acknowledge that parts of our capitalist culture are backwards. I don’t think I know anyone who doesn’t agree that teachers are not valued and paid enough. However, I do think you can still find many who do not see the importance of parental leave for both parents, or the importance of increasing the value of care.

I see the dire need for both female representation and the need to elevate the importance of care in order to break down patriarchy

To me it is a no brainer that investing in mothers, children, and care workers not only improves the wellbeing of society, but it also creates more opportunities for our economy to grow and thrive. I have no data to back this up, but I can only imagine how some of these changes could heal the biggest wounds our nation has—if children and the care of them was held more valuable and to higher standards, maybe we would see less mass shootings and stronger communities and find ways to bridge the gaps of polarization.

I can only hope that future generations will have the opportunity to live more balanced and whole lives. And on that note I would like to thank you all for the opportunity to be a part of this project and to share my story.

It’s basically you’re taking care of your child and the house and I mean…

who doesn’t know how to vacuum?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!