“The biggest love is honesty”

Amy is joined by Sarah Lopez to discuss Julia Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies and discuss the complicated history of patriarchy and revolution in the Dominican Republic.

Our Guest

Sarah Lopez

Sarah Lopez is a recent graduate from Boston University where she earned a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations (with a regional focus on Latin America) and two minors in Italian and Political Science. She is interested in substantive democracy, social movements, anti-racism, identity, migration, and Latin American politics, and aspires to obtain a Ph.D. and teach.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In her book, The Chalice and the Blade, Riane Eisler presents two different ways that human beings have organized their societies throughout the ages. One mode of organization she calls “dominator culture”, and the other she calls “partnership culture”. Dominator societies have the following features: rigid male dominance where one man or one small group of men enforces their will over all of the other men and all of the women, a high level of violence and abuse, and a system of beliefs that normalizes such a society. On the other hand, a partnership model is characterized by democratic ideals rather than hierarchies, equal partnership between men and women and people of all genders, a lack of tolerance for abuse and violence, and the belief system that validates an empathetic perspective.

Over and over again throughout the podcast, we’ve seen examples of dominator ideologies taking over their societies and causing all kinds of suffering. And we’re going to talk about another example today, the dictatorship of General Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic in the 20th century. And we’re going to learn about this history of the Dominican Republic through the book In the Time of the Butterflies, and also more of the history of the Dominican Republic more broadly. And here to help us do that is our guest, Sarah Lopez. Welcome Sarah!

Sarah Lopez: Hi, so happy to be here!

AA: So happy to have you here. I’m wondering if you can start us off by telling us a bit about yourself?

SL: Sure! I’m Sarah, I use she/her pronouns. My mother’s from the Dominican Republic and she immigrated in the early nineties. My father is Honduran and also immigrated in the early nineties. So I grew up with this awareness of immigration of other cultures. I wouldn’t really call myself American, but I’ve definitely now grown more attached to that label just by nature of growing up in the US. I grew up in a super multi-generational family. I was surrounded largely by my mom’s family, and my grandmother mainly as the central figure in our household. And I’m the only female-identifying person in my family among the children. So, the only daughter of five children, which means I was very aware of gender and structures from a young age just by nature of my brothers being treated differently than I was. Or, you know, seeing how my uncles interact with my aunts, things like that. So very aware, knowing that I wasn’t the same as my other siblings just because I was a girl, I guess. And particularly with Dominican culture, I’m more tied to that side of my heritage just because I was raised by my maternal side of the family. My father is great, but we just weren’t near his family very much.

One super interesting thing about how I was raised is that my family was centered around my grandmother. We didn’t really have a large patriarchal figure by the time I was born. So my grandmother, I guess we could call it matri-central, so around my mother and my grandmother. But I wouldn’t yet call it matriarchal because it can’t really be that way with how society is set up. So I was very much surrounded by really strong female figures and very strong women with very strong personalities. A lot of my aunts are single mothers so the men in my life were mainly my brothers, not adult older men who had power over me. And I was very much influenced by having strong women and strong leadership in my home, so very much “rah, rah, go women!” And I always say that I’m really happy my brothers grew up having an older sister, because I’m the eldest, because I always say they’ll just be a little bit more cognizant of gender roles. Because I made them aware of that and told them, “Hey, it’s not fair that you get to do this and I don’t. I’m going to do it too. And if that happens in your family, you need to change that.” Or, you know, my mom being a very strong personality means that they learned to respect women really early on because my mom sort of demanded it, especially because she’s a teacher. So a lot of layers play into how I’m influenced and how I view womanhood and the patriarchy.

I can also say I was raised religiously, so this also plays a role. I was raised as a non-denominational Christian and most of the people in my family are religious. I was very much impacted by the views of women in the family in the Bible. So, strong leaders in the Bible too. And also the weird dichotomy between having very strong women leadership in my home, but outwardly presenting as a godly family with the man as the head of the household. When it didn’t really work that way internally, but sort of putting on this show of a godly family with the father as the head when that wasn’t super true. My dad is very involved in my life, but he’s not the stronger of the two. My mom definitely makes most of the decisions and is very head-on with everything. So it was interesting to see how our families operated externally versus internally.

So aside from that, I study international relations. I’m a senior at Boston University, so I’m very excited I’m in my last semester. I study cultural anthropology in Latin America specifically, so, basically thinking about how people influence culture and vice versa and how that has an influence on policy. A lot of thought around which one is more important, culture or policy, and which one informs the other. So that’s what I like to think about. Outside of that, I love music, I love murder mysteries, I love new recipes, and I like being creative. I’ve lately been getting into more cozy ways of life, you know, very much trying to build a cozy adulthood now. So that’s been my focus.

AA: What a great goal, I love that.

SL: A little bit more is that I have a few goals for the future, mainly being a college professor, that is my main career aspiration in life. So getting a PhD and hopefully teaching at a university, I would love to do that. I am really into languages, I currently speak Spanish and Italian, and I would love to know all the other Romance languages. And ultimately just contributing to something larger than myself, which I’m doing here, and hopefully will continue to do in other spaces in my life.

AA: Oh, that’s fabulous. That’s so great. One thing that I love about what you said, it’s just so interesting hearing about your family culture and how there are such complex dynamics in all families and in all communities. And it’s just so rarely as cut and dry as, you know, patriarchy equals A, B, and C. You know what I mean?

SL: Absolutely.

AA: And even in my introduction, dominator cultures, that is how I introduced it, equals A, B, and C. And partnership cultures equal A, B, and C. But it doesn’t play out in such a clear cut way often. And that’s going to be a theme actually in today’s episode, where even in In the Time of the Butterflies, which is the name of the novel that’s based on real historical events, but these are extremely strong women in a very matrifocal family. And yet, still patriarchal norms are so pervasive. And there’s an interplay between the two, right?

SL: Absolutely. And you can really see them struggle against that and also be aware of how hypocritical it can be. Where they’re like, “We’re in this patriarchal society, but I know more than my husband, and I’m more educated than my husband, and I can do more than he does, and I do.” So, what’s really going on here?

AA: Right, exactly. It’s really interesting. It’s kind of hard to figure out on a personal level, and that’s where all of this happens. It’s personal. It’s between human beings in real families. Even in the government, you think of government as this entity that’s not personal, it’s just people in a room. You know what I mean?

SL: Absolutely.

AA: You kind of realize, I’m sure you’re starting to realize that, maybe with some fear, as you get older you’re like “Wait, who’s in charge of the world?” It’s just people!

SL: Absolutely, it’s just people! That makes it less daunting, but also so much more terrifying. Because it’s just people that were allowed into a room, and other people just decided that

AA: Yep. Welcome to the adult world, it is a terrifying place. But it gives me hope to hear people like you going out and going to make changes in the world. Well, let’s dive into a little bit of the history, and if you can acquaint us with some history of the Caribbean in general and the Dominican Republic specifically, that would be great. Just to give us a bit of the lay of the land.

SL: Definitely. The Caribbean and the Dominican Republic have a super long history, as do a lot of places in the world, but especially the Dominican Republic. The island that holds it was originally called Quisqueya, you’ll still hear that sometimes. It’s also a way that a lot of Dominicans and Haitians refer to themselves, as quisqueyanos. It was largely populated by the Taíno people which were an indigenous group from the Arawak people, which is the larger indigenous culture that pervaded most of that side of the hemisphere. They populated a lot of the Caribbean: Cuba, Jamaica, The Bahamas, Puerto Rico, and some of Southern Florida.

And their structure in terms of gender was pretty matrilineal. Social status and residences as well as inheritances were passed down through the women in the family, so one would live in the village of their mother. Chiefdom eligibility was passed through the mother’s side of the family. While both men and women were able to be chiefs, it would largely be determined by your mother’s social status. Women in the family were largely autonomous. They had extensive control over their lives and bodies in a way we don’t really see anymore, or are starting to see again. Many indigenous cultures still hold this, but outside of that, it’s really not seen anymore. They participated in huge aspects of political culture. Many women were chiefs and continued to be chiefs down the line. And they were largely responsible for agriculture and food production, which was the heart of indigenous culture, nutrition, and so they were hugely important roles in the family. And it’s sort of what you see in the partnership culture that you mentioned at the beginning.

We’re in this patriarchal society, but I know more than my husband, and I’m more educated than my husband, and I can do more than he does…

In the winter of 1492, early 1493, you see first contact with the Europeans. And this is largely the West Indies that Columbus mistakenly calls the Caribbean. He lands first in The Bahamas, but when he does land in the Dominican Republic in January he renames the island Hispaniola, which you will hear most people refer to as when they’re talking about the whole island, geographically speaking. On most maps, it’ll be labeled that as well. So fully erasing the name Quisqueya from written history. It’s still very much orally said, but not really written down anymore or acknowledged by a lot of intellectuals. So it’s renamed and it becomes named “the Spanish island” for a slight translation.

And when they land, Columbus creates this economic system called the encomienda system, which is another form of slavery. And it’s a bit different from how British enslavement operated. It operates on a sort of quota for the indigenous people, and so there was a requirement to bring a tribute of gold, which was really abundant on the island, or spun cotton. And if you were unable to bring that to the European governors, so to speak, who headed these villages and took over the structure of the island, if you were unable to bring that to them, there would be insanely cruel punishments. You could lose a hand, you could have your child taken from you. And so we begin to see this sort of cruelty and it begins to kill off the Taíno people. There’s also the introduction of different bacteria, different viruses, different hygienic practices entirely. So we start to see both biological warfare and physical cruelty as well.

And at the same time we’re also seeing the enforcement of European patriarchal values. So women’s roles begin to change and they move from being these very autonomous beings to bargaining chips. So the first thing that happened when Columbus arrived was that he bargained the life of a woman for entrance on the island, which is a huge shift from being chief of an island to becoming an object. So we start to see that and it’s really difficult and confusing for a lot of people to move from being a fully human being with roles and respect and then moving to almost a form of currency.

AA: Wait, can you tell me more about that act? I’ve never heard that before, that Columbus traded… What woman was it?

SL: If I’m remembering this correctly, she was the daughter of a chief or related to the chief in the village, and was sort of brought onto the ship by request of Columbus as a peace offering.

AA: Oh my gosh.

SL: And they treated her very well from the very rare written reports. And it was just strange to me when I read about it, just thinking about like, hmm, she suddenly became not a person and rather a peace offering.

AA: Sorry, I’m just having a hard time believing that she was treated well. Why would they want a woman on a ship full of sailors who hadn’t had access to women in several months? There’s only one reason they wanted a woman on that ship.

SL: Absolutely. I don’t think she was treated well. But they claimed that that’s what happened to her. You get sort of one line or a footnote in a lot of historical sources and then you don’t really hear about her again. Which is really disheartening and also odd. Like really weird. It’s not really well recorded what ends up happening to her. So one can only hope that she gets off the ship, but we don’t really know. There’s another moment when they return to the Dominican Republic, so they’ve made several trips, and one of the trips away from the Dominican Republic, they took a few of the Taíno people to Spain to meet the king and queen of Spain. And this is when the encomienda system is sort of starting up and the king and queen are like, “What are you doing to these people and why are you doing this?” And it’s one of the moments where you realize that Columbus was actually a really bad person. Also in the eyes of his contemporaries, not just retrospectively, right now. So it is very strange.

AA: Well, wow. Thank you for illuminating that. I hadn’t learned almost any of that, to be honest. When I’ve learned about the Spanish Conquest of the Americas, it’s been more focused, I guess in just classes I’ve taken, on Aztec and Inca and kind of the other side of the continent. I have really not learned very much at all about the Caribbean and the West Indies, and almost nothing about Columbus. And in fact, when I was a kid, I’m the generation that was still learning about Columbus as a good guy. And so it’s been a transition from me to your generation that I’m really glad that the real stories are finally being taught in school.

SL: Yeah, and they definitely are. I mean, I remember in kindergarten, I definitely thought Columbus was this great guy. Like a hero. And I think in high school I really only learned that the West Indies were the Dominican Republic and the Caribbean. I had always assumed that he had made contact with the US because that’s sort of how it was taught.

AA: It was, yeah!

SL: So yeah, it’s great that you named that. It’s definitely not spoken about very much but it’s starting to now. A lot of people, especially Hispanic people, are starting to reckon with their race and ethnicities and what makes up our culture. A lot of people will begin to start thinking back to the Taíno people and trying to trace their ancestry there.

AA: Have you done that, Sarah?

SL: Actually, I haven’t. I’m really curious from the few classes that I’ve taken on African enslavement and the slave trade, I do know that if I were to trace my African ancestry or indigenous ancestry, a lot of it would be from the Congo. That was the main nationality that was enslaved and brought to the Dominican Republic. But I’m really curious to see how much of my culture’s attributed to that, because my grandmother also isn’t fully Dominican. Her father was a Black Englishman, so I’m curious to see where it all comes from.

AA: Yeah, that is really interesting. Okay, well this is fascinating history, so sorry to derail you for a moment, but you can jump back in wherever you were in the chronology.

SL: Yeah, so really early on, about 20 years later at the start, you get to see these revolts against violence. So a lot of people don’t talk about how combative and defensive people actually were of their culture and of their land. So you really start to see revolts against violence in the first decade or so of this contact. In 1519, this is the most notable early rebellion that you see. It’s called Guarocuya’s Rebellion, and that’s the name of the man who headed the rebellion. In a lot of history books he’s known as Enriquillo, a nickname for Enrique. Which is a little, you know, you can hear that it’s a little demeaning that he was given a nickname that would really be given to like a toddler. You wouldn’t really call a grown man that, but that’s how the Spaniards called him.

So Guarocuya was a chief of the northern geographical area of the Dominican Republic, and he was raised in a monastery. So, something that I didn’t mention at the very beginning was that when we had first contact with Europeans, we also had first contact with religion. And when I say religion, I mean more like the Abrahamic religions, so early Christianity and things like that. You get a lot of monasteries that are set up on the island and you see a lot of religion in In the Time of the Butterflies. So this is where its roots begin, with these Franciscan priests primarily having these monasteries in the villages. And they were largely a group of people who were against the encomienda system, but they were European, so how much could they have actually told Columbus no or told their governors no? So Guarocuya’s contact with the Europeans is through religion, through the monasteries.

When he comes of age, he takes on his chiefdom. And in 1519, his wife is sexually assaulted by a governor of the village in the territory that the governor controls. And he’s aware of the laws and the way the administration works, so he goes to the Spanish courts and he tells them, “My wife was sexually assaulted and there needs to be retribution.” Like, “You guys enforce the laws, you need to enforce this one too.” And he’s dismissed, and it’s not really written what they say but one can imagine it’s sort of like, you know, this doesn’t matter, it’s not a big deal. And he sees that happen and is completely ignored.

And he decides he’s going to leave, so he establishes the first maroon community in the Dominican Republic. Maroon communities are autonomous structures that exist and they’re usually in really treacherous geographical areas because that way they can be enclosed and not easily reached by other people. So the northern part of the Dominican Republic is very mountainous and super treacherous, so he decides to establish a maroon community there. And when that happens, there are raids going on, so they continuously form raids and they retreat back and they steal supplies and they retreat. And the Spanish soldiers declare war on this maroon community, but are unable to even start that war because they’re unable to navigate the terrain. So they can’t even make contact at all.

And so a few years later, in 1534, so this was going on for about a decade or so of raids and no ability of the Spanish soldiers to really enforce the war that they declared in 1534, you see the violent relationship dissipate. And this is largely because the maroon community encloses itself and stays where it is. And Guarocuya has talks with the Spanish governors and the Spanish are trying to negotiate for them to come back. And he says, “No, you’ll leave us alone and we’ll leave you alone and let’s leave it at that.” And so that’s what happens.

Within this time period, you’re seeing more maroon communities begin. More people are escaping, enslaved Taínos are escaping. You’re also seeing freed Africans who have now arrived on the island at this time begin to escape as well. So you’re seeing huge pockets of freed non-Europeans, and they continuously raid the island, raid the Spanish territory, and smuggle out enslaved people for most of this century. So you’re seeing a lot of little squabbles and a lot of little violent raids, but there isn’t really a full-blown war yet, per se. And we’ll see that in the 18th century. So throughout the 16th century, we see loads of these communities. And the most famous one, which I thought would be interesting to highlight, was called Le Maniel, which is on the border of what at this time is French Saint Dominique and Spanish Santo Domingo. So the Dominican Republic and Haiti. And it’s on the border, which is also mountainous. And the reason I wanted to highlight this one is because there’s particular notes about how women in these communities operated, and they were largely the ones who smuggled enslaved people out of the Spanish territories and into the maroon communities. They smuggled materials and people to freedom. So I thought that was interesting to highlight.

AA: Yeah, amazing.

SL: You’re still seeing the autonomous roles that previously existed continue to exist in these communities. And so I’ll quickly move into the most famous revolution on the island, which is the Haitian Revolution. It started in 1791 by Toussaint Louverture, and he led this very violent revolution. He’s a freed black man and he leads this very violent revolution against the French. And he then imposes this very European standard of living on what is no longer colonized by Europe. So it’s really interesting that he still decides to keep most of the structures in place. And then in 1805, the self-proclaimed Emperor of Haiti, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, invaded Santo Domingo and occupied it. So the Dominican Republic is colonized and occupied for longer than Haiti is. It only became completely independent in 1865, which is a little less than a century later than Haiti, which became free in the 1790s or began the process of freedom in the 1790s.

AA: Got it. So you have the side by side. I mean that’s one of the interesting things about the island, you have this side by side. You have French-controlled Haiti and Spain-controlled Dominican Republic, and they’re having their wars of independence kind of independently of each other, side by side. And so Haiti was independent first, then Dominican Republic. But one of these French guys who freed Haiti then tries to invade the Dominican Republic and take over the other half of the island?

SL: Yes, and does so successfully. I wouldn’t say that it’s a full occupation of the Dominican Republic. It was largely the southern half that was occupied by Haiti. And then you have other parts of it that are still occupied by the Spanish. So in 1821, the Dominican Republic declared independence from Spain completely, entirely. And there’s war that’s going on in the early stages of this. So there’s parallel revolutions happening. Of course, we have the Haitian Revolution, 1790s- early 1800s, that’s happening right after or maybe just on the cusp of the French Revolution. So French Revolution, Haitian Revolution… The Dominican Republic sees Haiti revolt, and this was the big scandal of the Haitian Revolution was that once you see people not in power revolt, you realize, “oh, I have no power,” and then you revolt also.

And so in 1807, this really interesting figure popped up in the Dominican Republic. His name is Simón Bolívar. And he began the fight for freedom in the Dominican Republic around 1807. And this is when Haiti is trying to occupy the Dominican Republic. So you’re seeing parallel warfare happening. So one, they’re fighting the Spanish, and two, they’re fighting the Haitians. And they’re trying to grapple with this really weird mixed identity because technically, Haitians and Dominicans have a lot of the same ancestry but just happen to be colonized by two different European countries. It’s really interesting. So you’re seeing them contend with all these things. And they’re finally liberated from Haiti in 1844 and final independence from Spain is listed as 1865, and I think that’s final economic freedom as well. Economic independence. So they become a free country in 1865. And then you see an occupation of the United States until 1924, which is unbelievable.

once you see people not in power revolt, you realize, “oh, I have no power,” and then you revolt also

AA: Yeah. How did that happen? I’ve never even thought about it, Sarah. How have I never thought about this before? Oh my gosh.

SL: From what I understand, the United States had a military occupation of the Dominican Republic in the name of “democracy and freedom”, and I’m saying all of these in quotes because that’s rarely ever true. When the United States occupies a place in the name of those things, that’s rarely ever true. And so they occupied in the early 1900s because they saw the Dominican Republic as a really important territorial stronghold. They have strongholds in Puerto Rico, they need the Dominican Republic because they need access to the Caribbean and the Dominican Republic provides that. So you get this occupation for about 20 years and they’re sort of expelled from the island. This president that the United States puts in place, and they’re like, “okay, this guy is going to be your president”, that’s when Trujillo comes in and he ousts him from office with a military coup and begins his dictatorship. A lot of revolts, a lot of violence, a lot of warfare, and super unclear identities, and then it sort of, boom, ends. And 1931 Trujillo is “president”, in quotation marks because he is really a dictator, and you have all of this potential to form the Dominican identity because it was never really one to begin with.

AA: Was he seen as a hero at first because he was a liberator after this stupid puppet president that the United States–

SL: 1000%. He’s known as the great benefactor. And it’s because he was the one who got US influence out of the Dominican Republic. So, unfortunately, a lot of people still regard him as this very important figure. And he was, I mean, he shaped a lot of the modern Dominican psyche, but he wasn’t the liberator that everyone says he is. He just happened to be perfectly positioned to paint this image of himself.

AA: Okay, wow. Well that was a fantastic history lesson. I’m so glad you’re going into education, Sarah, because you’re such a great teacher. This is so, so fascinating. And you’ve taken us through the first third of the 20th century, Trujillo has taken over, and maybe we can shift gears a little bit into specifically the aspect of his cult of personality that was very much patriarchal and around this Latin American culture of machismo. Could you tell us about that?

SL: Absolutely, yes. His cult of personality was very strong. I mean, he was in the Dominican army, he was a general, that’s why he’s referred to as “The General”. And he took over the entire government and because he was a military man, he presented himself as very strong, stoic, very much the stone-faced man that he was. And he was obsessed with this idea of domination. Power and domination, both politically and socially. Politically, he was very interested in being aligned with who the power was. So sometimes he would be aligned with the United States, and then during the Cold War he would shift and he’s communist, and then he would shift again. So he was constantly playing a strategy. He was constantly looking at what was happening in the world and choosing to align himself with the most powerful people there. And one way that he enforced this image was with god-like allusions. Often in the household it was required that you had a picture of the Trinity and you had a picture of Trujillo and those were the people in your doorframe. My grandma was born in 1931 so she was raised, married, and had children during this dictatorship.

AA: Wow.

SL: My mom was born in 1966, two years after the dictatorship ended. And she was the fourth child of her generation, so she already had a huge, bustling family. So my grandma really grew up with this idea of the Dominican Republic as a dictatorship and she used to say that you would pass the portrait of Jesus and you would cross yourself, and then you would say to Trujillo, “God bless Trujillo”, and then you would continue with your day.

AA: Wow.

SL: It was definitely a surveillance state. You were very aware of his presence, of who he was. And so it’s once again this domination that’s in the psyche. You know that Trujillo was watching you. And he had quite a few nicknames, I think I mentioned the benefactor one. He was the benefactor of the motherland. In The Time of the Butterflies, you’ll also hear him referred to as “el jefe”, or “the boss”, which he very much was. His personality was to be the most powerful and the dominator. And so that really defines what it means to be a Dominican man above all else. And by nature, a Dominican woman as well.

AA: Okay yeah, tell us more about that. What was the gender dynamic like at the time, and was there any pushback from women? Well, we know there is because that’s the topic of today’s episode. Is the pushback of the women against this machismo, and could you define machismo for us for listeners who don’t know?

SL: Sure. Machismo is this idea of a man with an extreme amount of power, but an extreme amount of sexual liberty and sexual libido. So a lot of it was about being a man’s man and being a player and having lots of women. It’s very common in the Dominican Republic at that time to have multiple wives. Usually you’d have your wife and then you’d have a lot of mistresses.

AA: You couldn’t legally have more than one wife could you?

SL: No.

AA: Okay, okay.

SL: No. So you could legally have one wife, because once again, we’re a very Christian nation.

AA: Right, okay.

SL: “One man, one woman,” so to speak. But there’s this sort of understanding that in order to be a man, you need to be having lots of sex and have lots of women. It would be odd to have one partner or to have had one partner at one time. It was definitely an understanding that a woman has one husband, but a man doesn’t necessarily have one partner. Usually there’s one main family that’s supported and then you have little mistresses to the side. I don’t even like calling the women mistresses because that feels wrong. But you have other partnerships that you’re supporting too.

AA: And did you say that that even played out in your family of origin too, Sarah?

SL: Definitely. My grandfather had multiple women. I’m only aware of one because the kids that he fathered with that woman were very close to my grandmother’s children. So my grandmother was aware of her and knew her. And sort of helped her financially sometimes too, because, you know, these women have this understanding of like, what else could you do? There’s no way to want the life that you’re living because who would willingly choose to be an unmarried woman with children in this super Christian, super strict culture? You wouldn’t want that because you’d be seen as this loose woman and you wouldn’t be able to keep a job. You wouldn’t have a standard form of income because you’re waiting on this man to send you money, who maybe one month all his kids need to go to school. All his “real kids”. Then your kids don’t get anything. So my grandmother always talked about sort of feeling bad, and she was never really angry at the woman but very angry at her husband for forcing this onto somebody else. It’s hard enough to support one family. It’s even harder to try and support them on your own. So, I’m very aware of my step aunts, so to speak. And they’re all very nice.

AA: Wow. I think that’s really insightful, and wise, and charitable. Also to talk about them as mistresses does have a certain connotation when really they were victimized by the system, which is what I hear you saying.

SL: If I could touch on one thing that I think is interesting in this era, you see feminism happen. Of course, this is parallel to feminism movements happening in the US too, and other places in the world, but you’re seeing two types of feminism. So there’s “feminism” in quotation marks, and this is the feminism of what you would call a Trujilista, or a woman who greatly supports Trujillo. It was a way to signify to the world that the Dominican Republic is a liberal democracy, and yes, we give women their rights. Of course we do, why wouldn’t we? Any sophisticated Western country would do that. But it was just a way to not show to the rest of the world that this is a dictatorship. That’s why a lot of people don’t know about it, is because Trujillo was a great marketer. He was incredible at shaping the image of a country. And so a lot of people were sort of like, “Yeah, the Dominican Republic is one of the democracies in the Caribbean, awesome.” When in reality it was this dictatorship for 30 years that had a very clean image.

So you see that, and so you see organizations like the Dominican Feminist Action begin to spring up and they’re defining what it means to be a woman in Trujillo’s government. And this is largely defined by maternalism and being a mother. There’s a lot of public health messages that come out at this time, and they’re talking about how a woman’s social obligation and political duty to her country is to be a mother and to have children, and to raise these children up in the way that they should go and to make sure that they serve their country. So at this point, abortion was a crime. It’s illegal. It definitely did happen, it was just unsafe and very not a great idea. So you see a lot of these traditional gender roles. Women are in the home, they’re mothers, they serve their country by having children. And then you have actual feminism in the Trujillo era. And this is largely because there’s an increased attainment of education happening at the same time.

One woman that I really want to highlight is Dr. Evangelina Rodríguez. She’s the first woman to ever graduate from medical school in the Dominican Republic in 1909, and she was one of the faces of the feminist movement. She was one of the most outspoken critics of Trujillo. She wrote lots of books and articles and talked about broad economic reforms and social reforms. At the same time, she provided a lot of medical access to poor people. And she was a Black woman, racially Black, phenotypically Black, and very much accepted that. She was unfortunately murdered by the Trujillo administration in the early ‘60s because of how outspoken she was. I don’t want to be graphic, but she was left at the side of the road. It was very much a death without dignity and without the dignity that she deserved. And so she was a great, great leader in the feminist movement that existed in the Dominican Republic at the same time.

AA: Oh, I’m so glad you brought her up. I’ve never heard of her before, so I’m grateful.

a woman’s social obligation and political duty to her country is to be a mother and to have children, and to raise these children up in the way that they should go and to make sure that they serve their country

SL: Alongside this idea of machismo is “el tigre” and it quite literally means “the tiger” or “the beast”. And it gives you an idea of what it meant to be a man. And it meant to have this prowl, this hunger. So, it’s really weird. And it was all about domination and power. Usually in urban spaces you’ll still hear it today. It’s usually a compliment for men, “el tigre” or “el tigraso”, it sort of just lets you know that you’re a man with lots of emphasis on the idea of domination and sexual prowess.

AA: And so Trujillo was seen as the most tiger of all the tigers, right?

SL: Oh, the biggest tiger.

AA: Let’s move on to the book that we read, which again, for listeners, this is a really great book. I thought it was such an interesting and really digestible and engaging way to learn about the Dominican Republic. Did you like it too, Sarah?

SL: Absolutely. This is my second time reading it. My mom made it required reading in our household.

AA: Oh, I love that.

SL: And I love it. I think storytelling is the best way to teach about a nation. So I thought it was phenomenal.

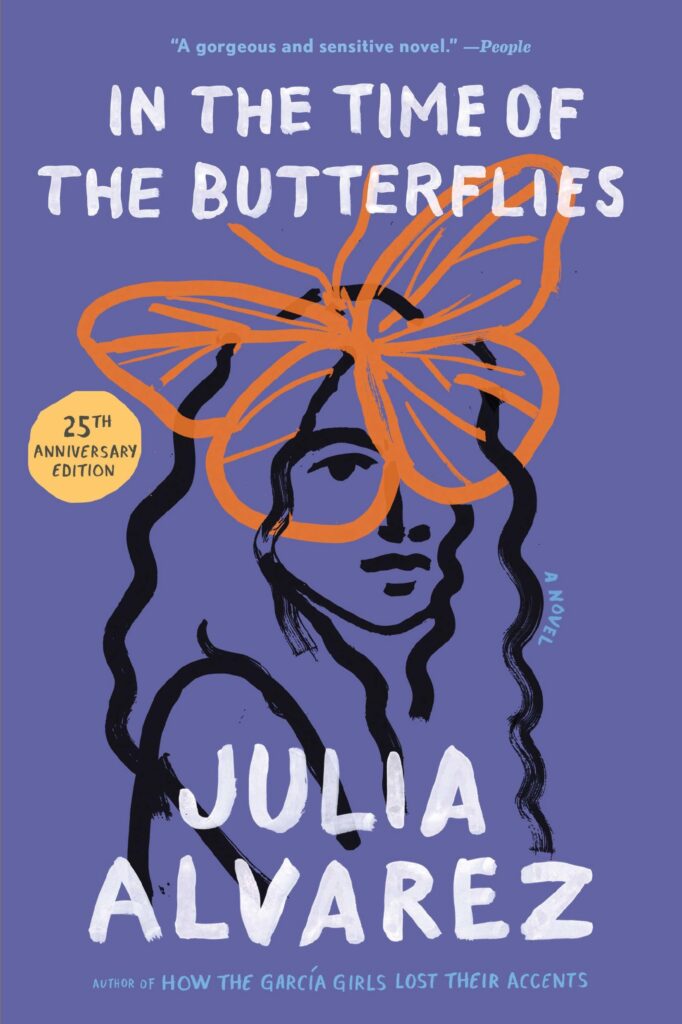

AA: Yeah. Highly recommended. It’s by the author Julia Alvarez, and I’ll just give a really quick summary of the book and a bio of Alvarez. The author was born in New York City in 1950, but her parents returned to their native country, the Dominican Republic, shortly after her birth. Ten years later, the family was forced to flee to the United States because of her father’s involvement in a plot to overthrow the dictator, Rafael Trujillo. Alvarez has written many novels, including How the García Girls Lost their Accents, another highly acclaimed and famous book. And then In the Time of the Butterflies, which we read. She’s also written many books of poetry and several books for young readers. She’s won many, many awards. She received the National Medal of Arts from President Obama in 2013, and she’s just a phenomenal person.

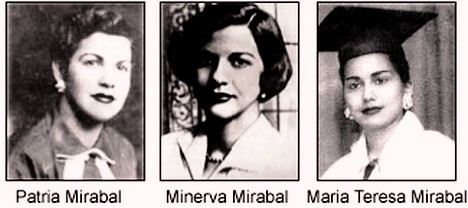

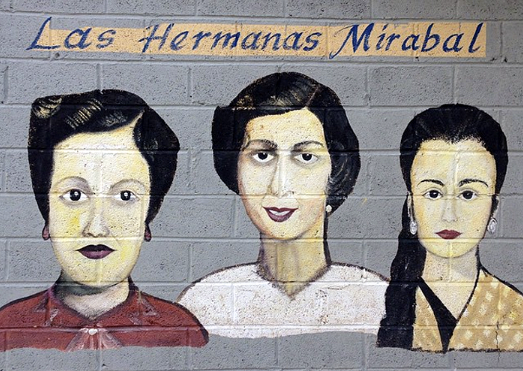

And this book that we read, In the Time of the Butterflies, was published in 1994. So really quickly I’ll also provide a summary. And spoiler alert, I am going to tell everybody what happened. This is the true story of four sisters. It’s the familia Mirabal and these four sisters were named Minerva, Dedé, María Teresa, and Patria. And they lived in the DR during this time when Trujillo was the dictator, which lasted, like Sarah talked about, from 1930 to 1961. And also like you talked about, Sarah, these sisters had grown up thinking that Trujillo was a benevolent and perfect leader. They had a picture of them in their house like everybody did, but it was at boarding school that Minerva, one of these sisters, meets a girl named Sinita and Sinita confides in her like, “I don’t want to tell you this, but you need to know the truth about the dictator, about el jefe.” Their glorious leader had arranged the murders of all the men in Sinita’s family. And so Minerva’s just spiraling, she can’t believe that this could be true about this person that she admired and that everybody knew was this wonderful, benevolent person.

But eventually she does believe her friend Sinita and the Mirabal sisters make a political commitment to overthrow the Trujillo regime. And they’re harassed and persecuted, and eventually they’re imprisoned and all of their family members suffer retaliation from the military intelligence service and then as vengeance for their political activities, Trujillo ordered that the three older sisters should be assassinated along with their driver, whose name was Rufino. And so one day while they were returning from visiting their husbands in jail, the women and the driver were stopped by Trujillo’s men and they were beaten to death. And then their vehicle that they were in, the car and their bodies were dumped off a cliff to make it look like it was a car accident and the car had gone off the edge of the cliff. So the death of those sisters, which many Dominicans knew as “the butterflies”, “las mariposas”, that actually was an event that incited the overthrow of Trujillo and a return to true democracy.

So I want to highlight a couple of things from the book, and maybe what I’ll do is read a passage and ask you what you think of it, Sarah, does that sound okay?

SL: Awesome.

AA: So one of the themes from the book was women’s participation in and perpetuation of patriarchy. And we’ve talked about this a lot on the podcast, that it’s not that all men are dominators and all women are victims of it. Like we said, it’s so much more complicated than that. First of all, patriarchy harms men as well. And even like I just read in that summary, these women’s husbands were also put in jail. Trujillo persecuted everybody regardless of gender. Everyone was terrified of him. Everybody was subject to his violent whims. And then in addition, a lot of women go along with patriarchy. They grow up indoctrinated in it, and they buy it, right? That’s why it’s so effective. Because a lot of people just believe it and go along with it.

One passage from this book was where one of the girls, I think it was Minerva actually, was saying that she wanted to go to law school. And so I’ll read this passage:

“‘Ay, dios mio, spare me.’ But playfulness had come back into her voice. ‘Just what we need skirts in the law.’ ‘It is just what this country needs.’ Minerva’s voice has the steely sureness it gets whenever she talks politics. She’s begun talking politics a lot. Mamá says she’s running around with the Peroso girl too much.”

So again, here’s this example where it’s actually Minerva’s mom who’s like, “Oh great, just what we need, skirts in the law, and you’re being influenced by this other girl.” I wanted to ask you, Sarah, have you experienced women upholding patriarchy?

SL: Short answer: Yes, I have. And largely in the church or in religion. A lot of women learn this way of being, this way of being a godly woman. And it’s largely to defer to your husband. And I remember confronting my mom about this. I had spoken earlier about the internal and external hypocrisies that exist in my family, and I remember asking my mom, “You are not submissive to my father, you have never been that. And why do you enforce that so much?” And she was sort of stunned. She didn’t really have an answer for me, but it was something that she had always taught me. The head of the household is the man and the woman follows. And I remember seeing this image of an umbrella and the umbrella is God as the head male figure in the family, and then the husband holds the umbrella and then the woman always positions slightly under and then the children. And I remember being so mad because she would treat my brothers with a lot more freedom and a lot more trust than me. And I was always so mad. I was like, “I’m the oldest. I know more. I’m more experienced. You should trust me the most.” We’re still contending with this. She’s definitely a lot more able to see my perspective now. And she definitely trusts me a lot, but it’s these subtle moments of upholding the patriarchy where all of a sudden I couldn’t play outside with my brothers because I was 10 and I was hitting puberty. Or like all of a sudden Sarah’s walking around with a towel because she just got out of the shower. My brothers do that all the time, but I can’t do that. I have to wear a robe or I have to be fully clothed in the bathroom first and then leave. These small ways of diminishing who you are because that’s what the patriarchy does. It diminishes who you are for the sake of upholding this gender role or gendered version of yourself.

So you experience that and you get so sad. I remember being angry at first and then I was just sad. I was like, oh man, she also had to live her life like this. She’s a strong woman now. I can’t imagine how it was growing up being this loud and intelligent woman and being told constantly “you’re not going to be as smart as the man next to you”, or “you’re not going to be as important as the man next to you. Your opinion isn’t going to matter as much as the man next to you.” And you sort of internalize that. And she and I are very much two sides of the same coin. We’re both loud, we’re very opinionated, we focus on education a lot. And so I had to learn to be a strong woman through her and then also be confused when I would see her intentionally diminish herself. It wasn’t done to her. I mean, it was previously, but she would do it to herself as well. Just because she was so used to enforcing this idea of the patriarchy.

So, you know, when the mom says, “oh god, more skirts in the law” there’s probably a moment in which she gave up her dreams to have a family very young. Maybe she wanted to be the skirt in the law. Maybe she wanted to be Elle Woods and wear bright pink in a courtroom and was unable to obtain that education. I always think about how heartbroken mothers must be. I think a lot about this quote from Alok [Vaid-Menon] who’s an incredible, phenomenal person. And they talk a lot about how their freedom from the gender spectrum confuses a lot of the people in their family, particularly the women. And they say this thing like, “How dare you show me all the things that I could have done? How dare you?” And that’s sort of what you see happening with a lot of women who even now are very scared of the younger generation of women because they’re showing them all that they could have been and just didn’t have the opportunity to do so. Didn’t have enough voices or enough power, there weren’t enough cracks in the foundation yet to really tumble the system. And so you see this sadness and anger, “how dare you show me everything I could have been? How dare you? How dare you not have your dreams crushed? I got my dreams crushed. Why didn’t you?” So it’s very sad. And I used to approach it with anger, but now it’s more just compassion. I feel for you, I’m sorry. But at least I get this. And so my mom understands that now. It’s like you get all the opportunities I didn’t get.

AA: Yeah, that’s amazing. And actually it leads in perfectly to one other quote on this topic that I wanted to share from the book where Minerva says: “One time I opened a cage to set a half grown doe free. I even gave her a slap to get her going, but she wouldn’t budge. She was used to her little pen. I kept slapping her harder each time until she started whimpering like a scared child. I was the one hurting her, insisting she be free.” And I feel like that’s really similar to what you were just describing. Sometimes when I’m talking to a woman of an older generation and I’m like, “Can’t you see?” And like you said, showing them the freedoms that they could have had only hurts them and then makes them angry. That’s such a complicated psychological dynamic that’s going on, and I really appreciate how you described feeling sad and maybe feeling angry, but then showing compassion to these women who really were the victims of this system, especially older women.

One more topic from the book that I wanted to bring up is this ambivalence that women feel toward men in general. And so these Mirabal sisters, they have this really complicated relationship with their dad. Because like we brought up, the dad has other families that they find out about. It really hurts their mother, they’re completely disillusioned and devastated to know that their dad’s been sleeping around and has all of these children. So they have half siblings, it’s super difficult. So they have this really complicated relationship with their dad and then with their husbands. Some of their husbands are definitely nicer men than others. And then they’re learning about Trujillo. So this is a part where Minerva is actually talking with Sinita, the girl that I mentioned before, when they’re in school. And so this is in Minerva’s own mind:

“‘Trujillo is a devil,’ Sunita said. But I was thinking, ‘No, he’s a man.’ And in spite of all I’d heard, I felt sorry for him.”

that’s what the patriarchy does. It diminishes who you are for the sake of upholding this gender role or gendered version of yourself…

So that’s one passage. And then later in the book, a lot of the women characters, now that they’ve become acquainted with the bad behavior of the men in their personal lives and also Trujillo, they start to distrust men in general. And then there’s this part in the middle of the book where some of them are just raging and one of the characters says, “I hate men. I hate all men.” And I just wanted to talk about this at the end because I think a lot of listeners will be able to relate to this ambivalence and really struggling. Because when we learn about a personal betrayal of a husband or a dad, or whether we learn about horrible violent crimes that it’s almost always men that they perpetrate, sometimes it can be a real struggle. So what do you think about that, Sarah?

SL: Personally, it’s almost like you go through the stages of grief. You’re almost like, “Oh no, the men in my life are not like that.” And that’s denial. And then you go through anger and you’re like, “Oh my god, every man I’ve ever met is the worst person ever.” And I think, especially me being an older sister and having younger brothers, I then made a vow that my brothers will not grow up to be like all these horrible men. They cannot. If they do, I’ve failed as a sister. There’s no way they’re not doing it. And I’ve had screaming matches with the youngest over this because he’s a teenager and he’s getting into like alpha male things. And he’s a sports guy, so he is very much a traditionally masculine guy. And sometimes we get into these arguments because I’m like, you know it’s not fair, you know it’s wrong. And he’s never been outwardly misogynistic or anything like that, but I get so nervous. I’m like, this is a slippery slope. You like football, man. Have you tried coloring books or something? Wanna get into sewing? I’m trying so hard to not let my brothers become the men that I hate. And it sounds so horrible. I don’t want to hate my brothers, I don’t want to hate my dad, I don’t want to hate my uncles. But sometimes you feel this genuine rage that it’s not fair. It’s not fair. It’s not fair, and how dare you.

And I don’t know if there’s an easy way out of it or an easy way to not be so angry. I think it just took me a lot of time to feel my anger and then not hold onto it and what do they call it? Holding nuance, you know? Being able to be like, “I hate men, but also the men in my life are very important to me. And I don’t want to hate them.” And then feeling these moments of hatred and then being like, okay, the patriarchy also hurts them. They’re not doing it on purpose. I just had to learn not to take it so personally, like when my brothers say some off-handed comment about some girl on the internet, I’m like, “Ooh, this is bad.” Sometimes you feel like they’re saying it to you or about you, and you’re like, okay, it’s not about me, it’s about the larger systems. Me yelling at my brothers at this moment right now isn’t going to teach them that patriarchy is wrong. It’s going to teach them that I’m an angry woman and scary, and let’s maybe not do that. Let’s push it to something else like asking questions.

So it’s hard because you don’t want to hate people in your life who are important. Both are true. You can hate the structures that create the men in your life to be the people that they are. And you can also love the men in your life. It’s just difficult. I think a part of this that seems very Latin American is this nuance. Specifically in Latin America, women are very outspoken about their hatred towards men. Very. There’s this sort of stereotype that Latin American women are fiery and passionate and it’s slightly, not slightly, it’s very misogynistic, of course, to push Latin American women into this one box of being fiery and sassy. But a lot of our culture is being outspoken against things that we don’t like. My mom has never once lied about her opinions ever in her life. If she doesn’t like something, you will know it. It’s a lot of hitting things straight on. Hitting your hatred straight on, too. If my mom doesn’t like something that my brothers have done, they will know. They’ll know about it.

AA: And they’ll probably still know that she loves them, right?

SL: Absolutely. There’s that nuance. The biggest love is honesty. You can’t love someone and lie to them. It’s impossible.

AA: Yeah. I love this. I love this, Sarah. Because just like we talked about when we encounter patriarchal beliefs, one phrase that’s helpful to me is to be tough on systems and soft on people. And so to say, I will call out that idea that you just espoused, whether it’s my little brother or a friend in a conversation, to say “okay, let’s talk about that because that idea that you just endorsed is really hurtful to me.” Or “let’s interrogate that a little bit and be tough on that system, tough on that idea.” But recognizing the humanity and that they probably inherited that idea from somewhere. They didn’t invent it. They might be grateful for that soft approach that enables them to learn without being humiliated. And of course there will be people who aren’t humiliated and who do espouse harmful ideas. And then we can continue to be hard on those ideas. But it does require a lot of high-level communication skills. A lot of love, but a lot of honesty. And I really appreciate that. Well, Sarah, this has been such an illuminating conversation! I’m so grateful for everything that you taught us today. Thank you so much for being here.

SL: Thank you for having me, it was a pleasure.

I then made a vow that my brothers will not grow up to be like all these horrible men.

They cannot. If they do, I’ve failed as a sister

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!