“women are the ones that know what to do with their bodies”

Amy is joined by Natalia Calero to explore the history and present day realities of reproductive rights in Latin America, as well as intersections between feminism, class privilege, and colonialism.

Our Guest

Natalia Calero

Natalia Calero is the General Director of Coming Up, an organization dedicated to gender equality, labor inclusion and professional development, whose mission is to help organizations have inclusive work spaces in which the talent and skills of all people are valued. Natalia has more than 20 years of work in national and international organizations in the field of human rights, gender equality and inclusion. Natalia served as a program management specialist at UN Women Mexico, where she was in charge of women’s leadership and political participation and the elimination of violence against women and girls. Prior to that, she served as an advisor to the Human Rights Directorate of the Mexican Supreme Court, where she supervised training on equality and the elimination of stereotypes.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In 2001, a pregnant 25 year old woman in Argentina named Luciana Monson discovered that the fetus she was carrying had a birth defect called anencephaly. The word “anencephaly” is from Greek meaning “without a brain”, and it means that the majority of the brain does not form. The condition is fatal, usually in utero, but sometimes death occurs hours or at most days after birth. Luciana Monson decided that the best course of action was to terminate the pregnancy, but in order to do that, she had to ask for judicial approval. First, one judge and then another excused themselves from dealing with the request and the case went to the Supreme Court of the region where she lived, which dictated that the first judge should decide. By that time, however, the pregnancy was so advanced that Monson had to take the pregnancy to term. The baby was born spontaneously, weighing barely over one pound, and died 45 minutes after birth.

In 2006, also in Argentina, a 19 year old mentally disabled woman was raped. Four months later, her mother discovered that her daughter was pregnant and went to the public hospital to request an abortion, which was allowed under the provisions of the penal code of the area which specifically allows abortion in the case of rape against a mentally disabled woman. The ethics committee of the hospital studied the case and gave its approval, but then a judge prohibited the abortion based on personal convictions. The block had to be appealed and the Supreme Court of Buenos Aires overruled the judge. Keep in mind that every single day that these judges and lawyers and committee members were debating, this real woman’s life continued and her pregnancy continued. So by the time the abortion was approved, the physicians at the hospital said that the pregnancy was too advanced.

In 2020, you may remember that Argentina was in the news as thousands of women marched in the streets, demanding that the government honor their reproductive rights. These women chose green as the color of their movement and the “Green Wave” activists eventually won the right for Argentine women to make their own choices regarding their own pregnancies. Green Wave activists also achieved the decriminalization of abortion in Colombia and exemption to the abortion ban for cases of rape in Ecuador. And, in 2021, the Supreme Court of Mexico issued a unanimous ruling that decriminalized abortion in the country. The Chief Justice credited Green Wave activists for shifting the national consciousness on the issue, as well as the position of the Mexican Supreme Court saying it kept getting harder and harder to go against their legitimate demands.

Today we’re going to talk about reproductive rights in Latin America, and to help us understand this ongoing struggle I’m so excited to welcome to the podcast Natalia Calero. Welcome, Natalia!

Natalia Calero: Hi, Amy, it’s nice to be here.

AA: Thanks so much for being here. I’m so excited to have you share your expertise with us, and I’m wondering if we can start out by you telling us a bit about yourself, where you are from, your education, and a little bit about the work you do.

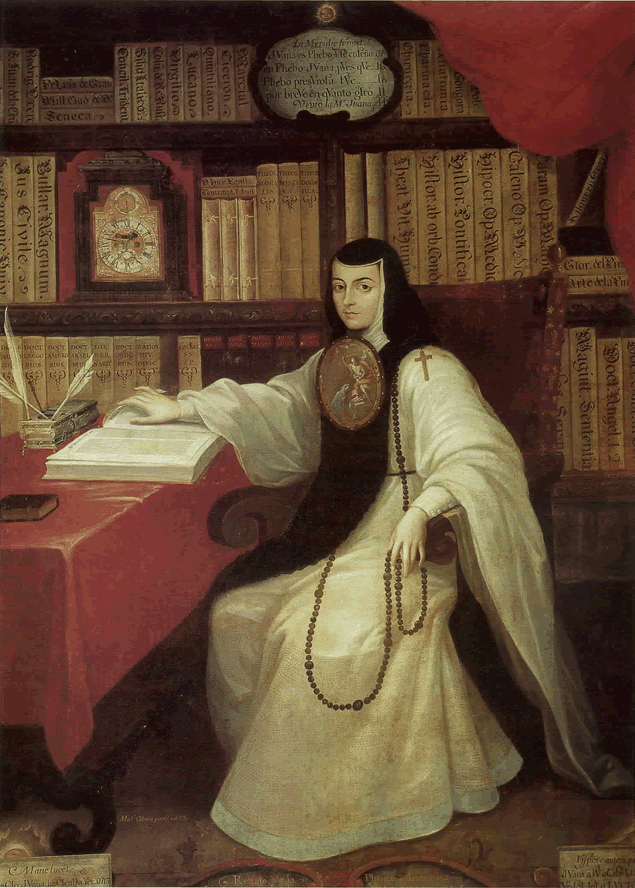

NC: Yes, of course. I’m Natalia Calero. I am a Mexican feminist woman, I was born to a Mexican woman and a Spanish father. I’ve lived almost all my life in Mexico City, and I’m so privileged to have access to a good education. I am a lawyer here in Mexico and I have 18 years of experience as a public servant in human rights policies. And in the last 10 to 12 years I’ve been working on gender equality. So I was this kind of girl that in high school was reciting Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz poems on feminism. I didn’t know exactly what feminism was about, I didn’t read Simone de Beauvoir when I was 14, but I was very convinced that women did not have the same opportunity. So that was a social fight, a social battle that I was drawn to since I was 12 years old. In the last two years, I quit my job at the United Nations and I started a platform called Coming Up, which aims to implement evidence-based inclusion and equality policies and improve women’s leadership.

AA: Fabulous. Can I ask what you were doing at the UN before?

NC: Yes, UN Women. I worked as a program manager, I used to be in charge of fighting against violence against women and girls, and women in politics.

AA: Fabulous. I love this and I love that you brought up that when you were young you recited poems by Sor Juana de la Cruz. That’s amazing! And I actually never knew who she was until I started this podcast and read all about her and read some of her poetry. And it’s so fun to me to hear that mentioned and know that she was part of your growing up and that you knew who she was. Was she taught in school when you were growing up in Mexico City?

NC: Yes. Not as much as now, because, you know, women have been invisible through history. But I was looking for a poem because I used to be part of these contests, and when I read ‘Hombres necios que acusáis a la mujer sin razón’, that’s one of the most known poems, I said, “this is me”. Even though it was written in the 17th century, it’s so relevant now that it was scary. So I used that and I won in my school!

AA: Amazing! That’s so great, I love knowing that. So let’s dig into the content that we wanted to talk about today, which is basically the struggle for reproductive rights in Latin America. We began with two stories in Argentina, partly because I know that Argentina has been getting a lot of attention in the last few years because of the Green movement. But as I mentioned, it’s been a really big deal really recently in Mexico as well. Is that right?

NC: Yes. Well first of all, I would like to say that when we listen to these stories, these are everyday stories for not only Latin American women, but African women, Asian women, and this is patriarchy. Rita Segato, who is an Argentinian feminist, says that women’s bodies are the first territory to be conquered by men. So we’re really talking about autonomy, because of course, if men were the ones who got pregnant we wouldn’t be having this conversation. So all these battles, social battles, sexual and reproductive rights are dated from the sixties, the seventies. But here in Mexico in 2007, in Mexico City specifically because as in the US these are local issues, these issues are managed in a local way, in Mexico City there was a change in the penal code that allowed women to have an abortion with no penalty in the first 12 weeks. And that was the first time we had Marcelo Ebrard as a governor here in Mexico City. He names himself as a feminist and he was surrounded by women such as Leticia Bonifaz, who was the legal head of his team, who really pushed to have this decriminalization for the first 12 weeks. And that was, I guess, the first great moment in legislative history for Mexico.

After that, there was a constitutional pledge that was presented to the Supreme Court in 2008. Decriminalization, but also the health rule was modified in order for women to have access in public hospitals to this service. Because it was not only like in the US in the seventies, the permission to have an abortion, but also as a public policy giving the space to have that. Because I’m going to say this very clearly: Middle-income women have always had the opportunity to have a safe abortion. And it was not the case for poor women.

Middle-income women have always had the opportunity to have a safe abortion. And it was not the case for poor women.

AA: I’d love for you to develop that a little more for listeners who haven’t really thought about why that would be the case. Do you want to talk about that just a little bit more? Why have middle-class and upper-class women always had access to abortions even when it’s illegal?

NC: The rich ones had the opportunity to travel to the US and there were some renowned doctors that really believed in this autonomy and who gave the opportunity for women to have an abortion. Fortunately, abortion has changed over time. Now you can have safe access to abortion with some pills. It depends on the week that you are in your pregnancy, but in general, it’s easier than before. But there were some doctors that although of course it was not legal, it was a very safe procedure. But it was costly because of the risk they were facing, and poor women didn’t have that access. And those women were the ones that were really stretched because of financial needs, because they didn’t have access to public health and public education, so it became much more difficult for them. And that’s something I want to talk about later because with access to reproductive rights, as in all women’s rights, you will always see this intersection of being poor, being an indigenous woman, and how difficult it is for some populations to have access to this right.

Going back to Mexico City’s history, we had some women from all over the country coming to the city to have safe abortion procedures, but it took almost eleven years for another state to decriminalize abortion. Because what happened after the Supreme Court ruled that it was not unconstitutional, what happened is that some states changed their constitution in order to protect life from conception. Like an obstacle for these women to exercise their reproductive rights. And another thing that I really want to say is that when we talk about reproductive rights, of course abortion is one of the most known ones, but we’re also talking about obstetric violence. We’re also talking about maternal death, that was one of the millennium objectives that Mexico didn’t reach in 2015. We’re also talking about how reproductive rights have a relation with our professional development, maternity leave, and all the rights related to labor rights. And of course we’re talking about assisted reproduction. So it’s true that abortion always comes to mind when we’re talking about reproductive rights, when we’re really talking about all these rights that are part of reproductive health. And we could see that in the pandemic, those were the rights where the public health system took away the resources. Of course it was to face covid, but it was the first part of the budget that suffered because they are not considered as important for women.

AA: Can I ask you about some of those other health concerns that you just listed? One that stuck out to me was obstetric violence. What’s meant by that phrase?

NC: Obstetric violence is all the violence that a woman faces in the pregnancy and post-pregnancy period. For example, being gaslit by their doctors. Like, “No, you are not feeling this. No, you’re exaggerating.” Also, for example, here in Mexico being forced to be immobilized when you are giving birth.

AA: Oh, like tied? Can they still tie people to bed?

NC: Yes.

AA: Oh gosh! Like by arms and legs?

NC: Yeah, not to move. That was pretty common in public hospitals.

AA: For listeners who can’t see, because Natalia and I are looking at each other, she was gesturing to her wrists. So you’re tied, not only are your feet up in stirrups, but you’re actually tied by your wrists.

NC: Exactly. To the bed. And you cannot move. And that was a usual practice in public hospitals. It is for example, the violence that indigenous women face and not having the capacity to decide whether they want to have or not an epidural. You say that in English?

AA: Yeah, epidural.

NC: Yes, epidural. And not giving you the option to decide. That is a whole range of obstetric violence. And of course it’s worse when it’s faced by indigenous women, not because they’re poor, because it’s not always the case, but because they are treated in some hospitals that do not respect their beliefs or that they don’t treat them well. And those are cases that have been taken by the civil society organizations and that have gone through this judicial system. And there have been some rulings that recognize what obstetric violence is, and of course, in these last 15 years have some new norms in order for women to have safer pregnancies.

Maternal death is closely linked to poverty because those are in general, in a very large percentage, deaths that can be prevented. Of course, when you’re poor, when you don’t have access to public health, when you are an indigenous woman and you don’t speak Spanish, that becomes much more difficult. So there are a lot of people that prefer not to go to a hospital, and of course, that has some risks related to hygiene and security processes that are regular in a hospital.

I think that it’s important to understand that we do have an indigenous population in each country. I mean, of course you have some countries like Argentina, like Uruguay, that don’t have these big populations because of historic reasons. They didn’t have this, in Spanish it’s called mestizaje, race mixing, that you did have in Venezuela, Colombia, all Central America, some part of Chile, Brazil, Mexico, Guatemala, etc. So for example, here in Mexico, just to give you some statistics, 10% of the population more or less identify themselves as indigenous. So you really have to take into consideration, because you’re talking about 10% of the population, the ones that were here when Spanish people arrived, they haven’t had access to all the services or their human rights. So we really have to implement this intersectional lens that gives you the opportunity to see how they have lived in a different way. The access to all the public services that the people that are not indigenous have regular access to, like education, health, work, job opportunities, housing, and of course they haven’t had full access to their human rights because of discrimination.

AA: I do have to say too that the United States, I’ve heard this statistic quoted and it was just affirmed again, that the United States I think is the lowest on the list of developed countries in terms of maternal health. We have the highest maternal death rate of the developed world. So it’s an issue for us here, too. Also, discrimination and racism for women going to receive any kind of medical care is such an issue for us here too. So I mean, I just have a lot of empathy and can really relate. What’s the other thing that you mentioned? Oh, yeah. When you say “medical paternalism”, that’s what we call it here. Obstetric violence and like male doctors especially, sometimes female doctors too, just kind of having a condescending attitude and gaslighting and not believing their patients. I know it’s different from country to country, but I wish it were better for all of us and the United States has such a long way to go as well.

NC: Yes, because I mean, what I find not crazy but it’s like a cognitive dissonance all the time, is that maternity is always romanticized. Like a mother is the best thing that you can experience in life, but you don’t have the public support to really have healthy maternity. So these are the things that we have been fighting for. And of course there is always a conservative agenda that we have seen arise here in Latin America since 15 years ago, that believes that women should not decide over their bodies. And that, of course, is an agenda that is very well budgeted. So we have these anti-rights movements that want to go backwards. And when you work in human rights one of the principles is progression, that once you have achieved something you cannot go backwards. And that sounds good but it’s not true because you see, for example, in the US going backwards in women’s rights, that is really a concern.

Because we’re talking about human rights here, and you know, CEDAW is a convention against women’s discrimination which has already said, not only in the general recommendations but also in the observations to each country, that having access to safe abortion is a human right. And not only in violation cases and rape cases. For example, in Mexico, if you were raped you are not punished for having an abortion. But we’re talking here about full autonomy. I mean deciding over my body when and where I want to exercise maternity or not.

there is always a conservative agenda…that believes that women should not decide over their bodies

AA: Well, I’d love to bring up a couple of other issues. One thing that I read is that in Latin America there is quite a high rate of teenage pregnancy. I read that 38% of women become pregnant before the age of 20. Latin America is a gigantic place, so I mean this is an average that takes in a lot of very, very diverse areas, but still that is an astoundingly, distressingly high rate. So almost 20% of births in Latin America are to teenage mothers. And I was just reflecting on what that means on a micro level, the personal level, of what that means for each one of those young women. And then also the huge cost to society, right? If you have a teenage mom who then can’t finish school, and then often that traps that woman in a cycle of poverty for the rest of her life. Can you talk about that a little bit?

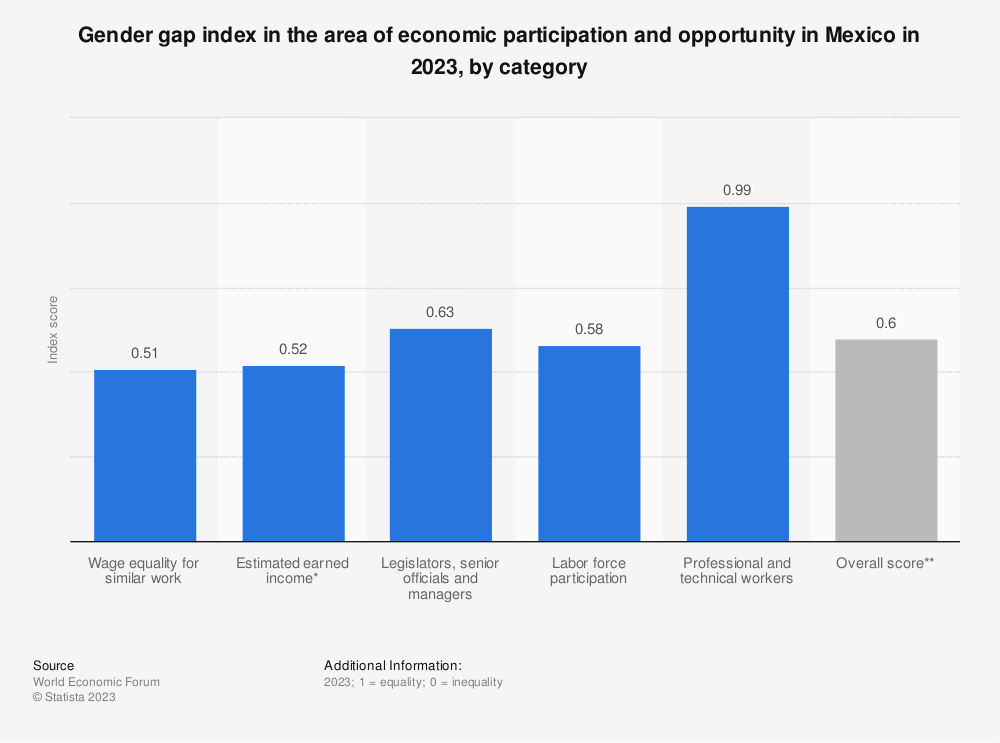

NC: Exactly. And of course you have to really see each country’s data. But here in Mexico that’s one of the scariest data that we have, because we did have backlash on this issue between 2007 and 2015, more or less. It has to do with a conservative point of view of the government that the government didn’t want to talk about pregnancy. Of course you need information, you need education, you need public access to contraceptives, you need science. And those are things that in a Catholic society it’s hard to talk about. Not only because of patriarchy, but because of religion, because of other systems of oppression. And the problem is that if you have this number that affects women specifically, that young pregnancies, as you said, impact their right to education, their right to work, and all the rights that are related to working conditions like housing, public health, social security that we have here in Mexico. And when you see the statistics, not of young women but in general, 66% of women that work outside their homes do it in an informal market. That means that 66% of women that work in Mexico don’t have access to public health, to housing, to maternity leave, to pension. So they are in a very precarious situation.

Imagine when you’re younger and you depend on your family, that’s where violence occurs also. They are trapped and there are no public programs to help these women, and you need resources to do that. And that is also linked to a national caring system because all the labor work that is done in Mexico, I’m not going to say that it’s only made by women, but women make like 2.6 times the care work. So we need to talk also about a public solution on caring for people, not only kids but people with disabilities, elderly people, that women are doing and that also is an obstacle for them to exercise other rights that are very linked to maternity issues.

AA: The thing that’s coming to my mind as you’re talking is the movie Roma. Did you see that film? If listeners haven’t seen that movie, I highly recommend watching it. It takes place in Mexico City, doesn’t it?

NC: Yes, and it’s on domestic workers. That is something that some countries like the US might not be so familiar with, but here in Latin America, not in Europe or in the US, in Latin America and in Asia, we do rely on these women. And of course they are underpaid, they don’t have rights. I mean, that is a whole podcast chapter on women and domestic workers.

AA: Yeah. But just to the point of a lot of the things that you were just talking about, she’s an indigenous young woman, and the patriarchal dynamics– she’s dating this guy and she’s just so timid in that relationship and he kind of acts like he loves her. Kind of convinces her to have sex with him and tells her it’s all going to be okay. And then she gets pregnant and he’s out of there. He specifically tells her, “Never talk to me again. Don’t come by my work again.” And she’s probably a teenager, like 16 or 17 years old but a domestic worker. And so this is the population that you’re talking about, that she’s maybe paid directly in cash by a family and so she doesn’t have any recourse if that family’s like, “You’re pregnant now, you can’t care for our kids.” She’s a care worker for this upper-class family’s kids. She’s completely vulnerable in society, there’s no safety net for her. If they were to fire her because she’s pregnant, she would be left really destitute. I mean, that’s not what happens, you’ll have to watch the movie to see what happens. But I was just thinking of this poor girl in that exact situation where she’s impregnated by a guy who can just walk away and if she can’t get an abortion and she can’t make that decision for herself, what is she going to do? She’ll be homeless.

NC: She will be trapped. And it seems like she has no autonomy to decide for her own future. And that’s the point, all these conservative agendas that put a lot of pressure on women to have kids, like, what are you doing to care for those kids once they are born? Because those kids don’t have access to education in a systematic way. And what is the role that men play in all this? Because, for example in Mexico, one third of families have a single parent that is a woman. We have all this social permission for men to not be part of their kids’ lives. So, like in the film, they just disappear. And of course, that is an extra load for the woman. It’s like all the consequences of raising a new generation are just for women. And when you don’t have access to public health, to maternity leave, to a safe place to raise those kids, it’s kind of a trap for women and their children.

AA: Yeah. On this topic of the conservatism that I imagine does come from the Catholic church, you mentioned that, but Latin America is still so very Catholic. And I wanted to read a statistic that I was researching where it says that Latin America is home to some of the few countries in the world with a complete ban on abortion, without an exception even for saving maternal life. Those countries are El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Honduras. In these countries abortions still happen, of course, they still happen at high rates, but they’re just performed in secret, often in unsafe circumstances. Then in some of these countries, these strict abortion laws are accompanied by really strict punishments. So in El Salvador, for example, a woman can be tried for manslaughter and jailed for up to 40 years for an abortion. And actually this punishment doesn’t even take into consideration the cause of the pregnancy such as rape, and sometimes it doesn’t even take into account that it can be a miscarriage and women are punished and accused of having an abortion when it’s actually a miscarriage. Can you speak to that a bit, Natalia? I believe, from some things I was reading, is that that used to be the case in Mexico as well. That there were extremely harsh punishments for illegal abortions.

NC: Exactly. And first of all, it’s not only some countries in Latin America, but since this is a local thing, there are five states here in Mexico that still don’t have the danger of maternal death in the penal code. So that’s that situation. You can find it even here in some states.

AA: Wow.

NC: So it’s a horrible scenario.

AA: I actually have a question about that. So does that mean… Okay, in the United States, like you said, it does vary state by state. Is that the same case in Mexico? So for example, if I live in a state in Mexico and I become pregnant and I will die if I carry that pregnancy to term, there are states in Mexico where I still would not have–

NC: Access to abortion.

AA: Wow. So then would I have to travel to a different state in Mexico?

NC: Exactly. And imagine if you live very far away from a state that provides that service, the cost that you have to go through in order to have access to that human right. Because we’re not talking about like ‘I prefer strawberries over that’, we’re talking about human rights. And yes, that’s the case in Mexico…I don’t want to be pessimistic here. First of all we have to thank civil society organizations and women’s movements that have been pushing this since the 1970s. And of course it has been a legislative effort, judicial effort, and what we were talking about before is that of course we have had these organizations that have helped women to get out of jail because of abortions.

AA: So, let’s say again that I live in a state that doesn’t allow abortion even to save the life of the mother, I find myself pregnant. I don’t have the resources to travel to a different state, that’s too expensive. I can’t take time off work, I don’t have money for gas. Where would I stay once I’m there? How would I pay for the abortion? It’s just too expensive, I literally don’t have the money, and I will die if I have this pregnancy and carry to term and so I do have an illegal abortion. Are you saying that I could be prosecuted by the state and go to jail in Mexico today?

she has no autonomy to decide for her own future. And that’s the point…

NC: Yes, yes, we do have some cases, in general of poor women that have been prosecuted. And of course, being part of the penal procedure is so complex here in Mexico that you need to have a lawyer. And a lawyer costs so much, so these civil society organizations do have free advice and they have helped women to get out of jail because of this. When you have so little budget for justice procurement, do you really want to put women in jail with all the problems that you have here in the country? I’m not saying that we shouldn’t punish crime, but we really need to think that that is not a crime anymore. As I said already, that is considered in international law as a human right. So why don’t we take all these resources to really make all the necessary policies for women to take control over their bodies in order for them to really give society what they are capable of?

AA: It brings it home to me too, really through the whole episode, in terms of “a woman can’t do this” and “she can do this, but not this.” And at the root of this, the issue and why we’re talking about it on a podcast about patriarchy is because the vast majority of the people in the rooms who are deciding these laws and these policies are all men. And they’re deciding what will happen literally in a woman’s own body. And to me that is the root of the injustice, is that men would presume that they would have the right to be able to make the choice about someone. I mean, I know it’s basic, but it is striking me again and again that the legislative branch and the judicial branch and the executive branch of government and the healthcare professionals, and the religious leaders, all the people who are saying, “What should we do about women’s bodies and their reproduction?” They’re all men. How are we accepting this as the system?

NC: Exactly. They are men and some women that–

AA: Let the men choose.

NC: And act under this structural patriarchy. And that’s why patriarchy is structural, it’s not an individual thing. And they work through all these religious or conservative ideas. And that’s why I told you before, if men were the ones who got pregnant, we wouldn’t have been having this conversation.

AA: Yeah, absolutely. Well, Natalia, this has been such a fabulous conversation. Is there anything that you’d like to share with listeners?

NC: We really have to see this as part of all other rights that women don’t have access to in equal situations as men. And it gets worse when you’re talking about some specific women groups like LGBT, indigenous women, poor women. And that in order for us to have a better society, we have to guarantee their rights. And the first basic right is the right that we have to do whatever we want with our body. We really have to understand that women are the ones that know what to do with their bodies.

AA: Wonderful. Thank you so much, Natalia Calero, for being here today. I so enjoyed this conversation and really appreciate you being here. Thanks so much.

NC: Thank you so much, Amy.

all these conservative agendas put a lot of pressure on women to have kids…

what are you doing to care for those kids once they are born?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!