“there arose this idea that women shouldn’t have power at all“

Amy is joined by Annabelle Qian to conclude their discussion of patriarchy’s history in Imperial China from the Qin Dynasty (221 BCE) to the Qing Dynasty (1912 CE).

Our Guest

Annabelle Qian

Annabelle Qian is an 18 year old scholar who just graduated from Waterford High School, and will be studying international affairs and economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill this fall. Annabelle is biracial and trilingual. She lived in Guangzhou, China for 10 years where she cultivated her study of the intersection between global politics and personal identity. Annabelle is an award winning historical writer; she has presented papers in Washington D.C. for international competitions, as well as at the Utah State Capitol.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Today we’re back for the second half of Chinese History. Last time we began with the earliest records of humans in China and we got all the way to Confucius in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty. And today we’re going to begin with the Qin Dynasty and follow the historical path all the way to the end of dynastic China in 1912. Our books, again, this week are Women in Ancient China and Women in Imperial China by Bret Hinsch. And I’m joined again by the incredible Annabelle Qian. Welcome, Annabelle!

Annabelle Qian: Thank you so much, Amy.

AA: Well, we’ve got a lot of fascinating stories to tell today, so let’s dive right in. In 221 BCE, Emperor Qin Shi Huang conquered the various noble states and unified China under the Qin Dynasty. And that marked the end of the period that historians refer to as Antiquity. So there’s a big, big shift at this point in history. So now we’ll launch into the Qin Dynasty, that was from 221 to 206 BCE and then it’s followed by the Han Dynasty. And this is kind of where we get the modern concept of China as we now think of it, right, Annabelle? Kind of this unified sense of a country of China is during the Han, and its ideologies created a foundation that would last throughout the dynasties after that.

One thing I found that was interesting from this period was that marriage law changed. So whereas before men could have lots of wives and lots of concubines, at this point in the Han Dynasty they said that a man could only have one legal wife, but he could still have lots of concubines. And then the government also specified a lot of details around divorce law. So a man could legitimately divorce his wife if he claimed one or more of the following reasons: that the wife was disobedient to the in-laws, if the wife was barren, if the wife was licentious, which means was promiscuous so I guess if she had an affair, he could divorce her for jealousy, meaning like her jealousy toward other women, he could divorce her for serious illness. And I was like Annabelle, think of Ivanov, because Annabelle was just in a play where there was a wife who had a serious illness. And anyway, if you’ve read Ivanov by Chekhov, you get the reference, right, Annabelle? But I was like, oh my gosh, I just saw you in this exact role! That was crazy. But yes, a husband could divorce his wife if she became seriously ill. He could divorce her for loquaciousness, being too talkative, or he could divorce her for theft. But the conditions in which a husband was not allowed to divorce his wife were if she had nowhere else to go, or if she had mourned the death of one of his parents for three years. I can see that being really widely used by wives. Like, you would almost pray for your in-law to die so you could mourn them for three years so you’d be safe, in case you got too chatty and he wanted to divorce you. He also could not divorce his wife if he had become wealthy after they got married. And that one seemed quite fair to me, like they were trying to protect women who– like, if she had married him assuming he would be poor, then they want to protect her from if he got a big fortune and then he wanted to just ditch her, that would not have been fair to her.

So, wow. They were trying to create some protections for women, but some of these strike me as a very low bar. I mean, being able to divorce a woman legally for some of these reasons, I mean, I was laughing but it’s actually quite heartbreaking thinking about it. But that was the part that was the most interesting to me. What were some parts for you, Annabelle?

AQ: Well, what I thought was really interesting was how we see this level of such extreme specificity in all these rules and regulations and that’s really starting to emerge, and that could definitely be seen in the household and how men and women interacted within marriage and like a huge shift in that. And a big part of that was just these insanely separate spheres that they lived within and how even if a couple was married, there were all these rules and regulations that kept them very separate and had them lead different lives. So, in the book, at the bottom of page 35 of Women in Imperial China, there’s this quote that says: “The men should not speak of what belongs to the inside of the house, nor the women of what belongs to the outside. Except at sacrifices and funeral rites, they should not hand vessels to one another. In all cases, when they have occasion to give and receive anything, the woman should receive it in a basket. If she has no basket, they should both sit down and the other put the thing on the ground, and she will take it up. Outside or inside, they should not go to the same well nor to the same bathing house. They should not share the same mat in laying down. They should not ask or borrow anything from one another. They should not wear very similar upper or lower garments.”

So yeah, that’s just crazy. Just this idea that they need to be so separate, they can’t even touch the same thing. They need to just not look at each other, not talk to each other, just their separate spheres. The woman is inside the house, the man is outside. They have their own responsibilities and they should never cross paths. So during this time women were responsible for creating textiles, which they could bring to the economy, to the market, and to trade with. And that was definitely good for them because at the same time, men were transporting grain to the market because they were responsible for the agriculture. So this was a very good thing for women because they had more economic freedom with being able to transport the textiles instead of grain like the men were doing.

A Han woman could own property in her own name, which was definitely a shift from previous dynasties. And under certain circumstances, a widow could exercise control over her dead husband’s property. If the deceased had an adult son, he would inherit all of the estate and the widow received nothing. But as men frequently passed away before their sons had grown to maturity, widows often took over as de facto head of household. So, next was the dowries. There was that bridewealth gift that the groom and his family would give to the bride to symbolize a marriage, but that kind of shifted into dowries, where a bride’s family would send her with money to a groom’s family. And that definitely shifted the concept of marriage and how that transaction worked later, especially in other dynasties.

And the next part was just some interesting stories about women of the dynasty. One was Empress Lü and her husband was Han Gaozu, who was the first emperor of the Han Dynasty. And when he died his son was technically the new emperor, but his wife was Empress Lü and she was regarded as the real ruler. She seized control of the government and stabilized the fragile new imperial system. She ruled with a lot of confidence, but sadly, after she died her whole family was killed. And this kind of set the precedent for people who would come in and kill an entire ruling family in order to rise to power.

AA: And I mean, her whole family was killed after she died by the person who then wanted power and didn’t want anybody claiming the throne after that, right? And they didn’t want to leave any room for contesting the authority.

The woman is inside the house, the man is outside. They have their own responsibilities and they should never cross paths.

AQ: Yeah, exactly. So they were competing families who wanted the power, and because it was this patrilineal system and it would just go down to the next heir within the same family, they had to, in their eyes, kill the whole family in order to rise to power.

This was also the rise of this idea of female black magic, where men began to fear powerful women a lot. And it became this poor reflection on a man if a woman got too powerful. And a big contributor to that was Empress Lü and women like her who would rise to power and then, in the eyes of men, have too much power and that would be seen as very dangerous. So it was said that women could harness black magic and use those efforts to endanger men or society or just disrupt the system as a whole. So there were lots of efforts to purge witchcraft, to gain control over women again. And thousands of women were murdered for being accused of using black magic.

AA: That was totally new to me too, Annabelle. Obviously we know that happened all over Europe and in the United States. I didn’t know that that had happened in China too. Actually, I’ve heard of that happening in an African context as well, but yeah, I didn’t know that about China before.

AQ: Yeah. I guess it’s just this universal idea that if women are too ambitious or have too much power, they must be evil and witches and just have to be stopped. Which is kind of sad to think that in so many distinct parts of the world, they came up with the same idea that they just really wanted to suppress and control women and make sure they didn’t have too much power. And then another story was about Ban Zhao, who was regarded as the most educated woman of the Han Dynasty and a really great female intellectual figure. In fact, the greatest female intellectual figure of any era, as it says in the book.

AA: Amazing.

AQ: Yeah. She taught women how to obtain a degree all within the patriarchal system. And one thing I found interesting was that she wrote this book, Admonitions for Women, which is the first surviving book written specifically for women and about women. And you can see a lot of Confusionist principles that influenced it, because she talked about basically how women should behave. And a lot of it doesn’t sound very feminist because she says women need to respect their in-laws and be quiet and courteous and helpful, and those are the values that they should uphold. But actually when you read it and see the influence of certain military strategists that she was also reading at the time, it kind of shifts the book into a new light and makes it sound more like this strategic survival manual for women who were going into a new house, into this foreign place where they didn’t know anyone and joining this new family. And it was actually a very practical and pragmatic guide for them, which helped them to survive because if they were too outspoken or too powerful, that was very dangerous for them. So she actually did end up helping a lot of women through this book.

AA: I think your insight is really important about her being pragmatic and practical about like, here’s how you’re going to be able to thrive, you know? And what can we realistically do within this system? I mean, I think that’s a really valid and important tack to take sometimes. That that’s actually all you can do.

AQ: Yeah, definitely.

AA: So the next era was kind of post Han Dynasty. And this was a little bit hard for me to make sense of, and that the chapter is titled “Order Out of Chaos”. I think there was a time of a lot going on. Hinsch describes rapid changes of leadership and invasions and migration patterns. And one part I thought was interesting was during a period of invasion from the north. So previously, central and northern China had been the cultural capital, and the south of China at the time had been seen as kind of an irrelevant backwater. Not much going on, very rural. But during this period of time, because of an invasion from the north, it forced the people in the north to move south and so the south then became the cultural center of the country. And the south started practicing the strict laws like the ones you just read, Annabelle, like all of these very, very specific gender norms, a lot of Confucian ideals. But I just thought that geographical shift was super interesting.

And then he talks about the different lives of the women in the north versus the south and how that reflected the cultural division of these two areas. So he writes that Confucian ritual norms waned under foreign domination, so people in the north were again, being influenced by this other culture, they had a lot more autonomy than before. So people who did stay in the north, women’s lives opened up. They could freely interact with men, they could receive guests, they could visit friends, conduct business in government offices, initiate legal proceedings, they could handle their own affairs a lot more. Northern women felt free to speak up and manage family life and they often controlled household finances. In contrast in the south, there were much more conservative customs that were inherited from the Han dynasty. They tended to remain modestly hidden inside the home and they completely avoided encounters with unrelated men. And in the south then, you know, women’s husbands handled the family’s money and property. And then some other parts of this period that we thought were important were two new influences that took hold. So, Annabelle, could you talk about Daoism and Buddhism?

AQ: Yes, definitely. This was definitely a huge shift when these new foreign ideologies came in that marked this great new opportunity for women to explore independence within the context of religion. And that actually gave them a lot more freedom that we’ll talk about later. But basically, Buddhism and Daoism were definitely foreign influences and they were very, very different from traditional Chinese values. So for Daoism, the idea was basically about living in harmony with the Dao, which was the way or the path and kind of the natural order of things. It emphasized balance between humans and the universe, and it definitely reassessed gender stereotypes and created this more positive interpretation of femininity. And Daoism had values that were more ungendered, and that was a liberating new intellectual climate for women.

Buddhism was brought to China by Buddhist monks from India during the latter part of the Han dynasty. And it took over a century for it to become assimilated into Chinese culture, but there were a lot of really important and interesting ideas from Buddhism. So, the values of Buddhism were centered around the notion of human suffering that could be overcome with meditation, physical and spiritual labor, and of good moral behavior that would eventually help one achieve enlightenment. Originally, all Buddhist monastics in China were men, but eventually women established the first order of nuns, and that’s when Sanskrit writings about female monasticism were translated into Chinese, which really helped establish the practices they would later continue. Women joined the clergy for a lot of reasons. One was just simply strong religious vocation, and the more common reason was escaping wedlock or the burdens of bearing and raising children. So if they became nuns, they wouldn’t have to get married or follow the traditional female archetype of traditional Chinese culture. And also monasticism provided them with many opportunities to study and travel and meet more people. And nuns had a unique freedom, especially in regard to education, where they could leave the house, they could study under important scholars, or journey to temples, and they could study both religious and secular writings. So I thought this was a really cool time where women used monasticism and Buddhism and other religions and cultures and influences in order to kind of escape this very traditional lifestyle and explore their own freedoms and their intellectual pursuits.

AA: Mm-hmm. That gave them another option. Again, because my education has been all Euro-centric, my point of reference was oh my gosh, this happened in Europe too. Where in the Catholic church, a lot of women went into cloisters and became nuns for the exact same reasons. But that was much, much later in Europe, and this is before the Common Era. And that was really surprising to me, too. That this happened a lot. When women are given another option, it’s actually such a good thing for them even if it means that they then can’t have a family. I mean, I think that was the case in Buddhism too, that nuns did not have families, so they would live in a community of women.

One thing that stood out to me from this era also was the emergence of what is called the Northern Wei Ruling House. And I’m assuming that this meant, this was like a clan, I guess, like a big influential family. And they had two practices that I wanted to talk about because they made a big impression on me. First of all, the emperor, when he was going to choose women to come into his harem of concubines, they developed this custom where craftsmen would paint a picture of the candidates for him to choose from. So he wouldn’t even meet the woman, a craftsman would just be like, “Do you like her? Do you like her?” Just present him with paintings of the women. I was like, oh, that’s like the origins of Facebook. Which was, I don’t know if you know that, but Mark Zuckerberg first created it as like a “hot or not” thing where men could rate women based on how hot they were.

AQ: Yes. Have you seen the movie The Social Network?

AA: Yep. So bad.

AQ: Oh my gosh, crazy.

AA: So bad. So yeah, that existed. Again, this is fabulous. It must just be the dark side of human nature because it pops up all over the world in all these different eras, right? Of just judging women on how they look. But again, not even in person. This just makes it even more efficient and easy, just based on paintings. And then the other one was that in the same Wei Ruling House, to avoid female domination of the government, which is what you just talked about with the kind of witch hunts, we just cannot have a woman in charge, they instituted a practice where after the emperor had designated one of his sons as the heir, it became customary for the boy’s mother to commit suicide by drinking poison. So once they knew which son was going to inherit the throne, that son’s mother was completely irrelevant. And they wanted to keep her irrelevant because they didn’t want her having any influence once he was on the throne by the bonds of filial piety. So they would get rid of the mother by having her commit suicide.

And after she died, if he was still a little child, like a toddler, then a wet nurse would be hired to raise the boy to adulthood instead of the mother, because that wet nurse would become the empress but would have no power. She’d have no influence over him because he didn’t owe her any filial piety because she wasn’t technically his mother.

I think a lot of times on the podcast I emphasize so many men are kind, and so many men are good. And that’s really true, and I tend to want to give the benefit of the doubt and say that people just inherit these customs. But this is an instance where it’s deliberately misogynistic. To have a mother commit suicide specifically to remove any feminine influence from the ruling power. It actually just strikes me as evil and horrible and it really stood out to me.

AQ: The next topic that we also thought was interesting was about the enslavement of women. So basically it started out with women being punished essentially for men’s crimes, basically a convict’s family could be punished for a crime that he committed. For example, his wife or concubines or daughters could be sentenced to forced labor or to work in a palace of slaves for a crime that a man committed. And men also could sell their wives into enslavement or enslave them themselves. And that was just really horrible to learn about, that men had so much power to the point where they could just give away women as if they owned them like property. And that those women could be punished for what he did and he could kind of use them for their forced labor and for all these practices that basically enforce the idea that women didn’t have any personal autonomy.

AA: Mm-hmm. Yeah, that was a really distressing section to read for me too. The next topic that I want to dive into just a little bit because we talked about it earlier, was that in this time, Chinese literature starts mentioning women’s jealousy a lot more.

AQ: Yeah. Well, when we were talking about the betrothal practices, we were saying it became very down to the basics about the money and about the transaction, and kind of these ritual norms went away with a lot of marriage practices. And that same idea transitioned into the marriage itself. And because of the decline of ritual norms, women had a lot more freedom to express their true feelings, particularly in regard to jealousy and infidelity of their husbands. And a lot of women resorted to violence as a response to jealousy. And another reason that this became talked about a lot more was the rise of concubinage and the increased number of concubines that men had. And that in turn fueled the jealousy of their wives and among the concubines. And there were lots of stories about women who became so jealous of the concubines that their husbands had and felt like concubines were favored over them. And that caused a lot of violence and a lot of very dangerous practices, and even murder in a lot of cases. And that reflected negatively on women in society because they were seen as being possessive for reacting that way to their husband’s infidelity. And this new idea emerged that tolerating infidelity and not being jealous was praised. And that was the value to uphold because that was being seen as more virtuous than the violence and than acting angry. So women who were jealous or resorted to violence were not seen as virtuous, and it became the standard to just kind of ignore it if they had those feelings of jealousy.

AA: Mm-hmm. It really struck me here that it was the women who are being blamed for being jealous when it’s the structure that’s put them into this terrible position, right? So the structure is bad and then like you just said, they’re like “a virtuous woman does not get jealous.” I’m going to read just one little part from this section of the book because it was kind of awful. But the author points out, like you did earlier, Annabelle, that wives were often– it was like an arranged marriage and the wife would have higher social status, and then concubines were chosen basically on their looks and whoever the husband kind of fancied. And so that meant that a wife could kill a concubine with impunity because nobody’s going to charge the wife with murder because maybe the concubine was a peasant or something. And it talks about this one family where a husband had impregnated one of his slaves, and the wife became so enraged by that infidelity that she beat the concubine to death. And then, I mean, it’s really gross, but beat her to death and then stuffed the dead woman’s corpse with straw, and then delivered the corpse to her horrified husband. And we know about that because it was recorded, but the way it was recorded was just like, “look at what this horrible wife did.” And yes, that’s horrible. I mean, that’s horrible. And also the person who gets punished is the concubine who is pregnant, that’s not her fault. And she’s probably raped, she’s basically a sex slave of this man, so it’s not the concubine fault. But to blame the wife and to not examine that the system is bad, I thought was just, again, really heartbreaking.

AQ: Yes, definitely.

AA: It was a really striking story.

AQ: Yeah. And the fact that the woman was probably in that position because of her husband and his actions, but of course, she can’t actually punish him or take the anger out on him. So instead the wife has to resort to taking those feelings out on other women because the husband will always be protected and elevated, that’s just really sad.

AA: Exactly. Interestingly though, in any particular era there are, you know, some areas where women are being more oppressed, but then other areas where maybe they have more rights than before. And around the fourth century, women began to have increased land rights. So the government gave everyone land to cultivate in order to help the economy, including women. So even though these marriage practices are just excruciating for women, at the same time, women could own land in their own name, which potentially gave them financial independence, which was awesome. And then you talked about women’s literacy earlier, and this was an era where women were known to be accomplished writers and poets. So those were some glimmers of progress for women during this time.

At the same time, this is when the concept of chastity for women began to really take hold. Obviously this has been an ideology for many, many centuries, but it started to be, again, more codified. Like really in the law and really have specific norms. Can you talk about that a little bit, Annabelle?

AQ: Yes, definitely. Like you said, there were some aspects in which women progressed and had more freedoms. But then because of this concept of chastity emerging, they were also becoming a lot more repressed during this time. A lot of women had greater autonomy which emerged as a result of changing property rights and financial regulations, and that kind of gave them more economic freedom. But then chastity was emerging as this concept at the same time, and that was regarded as a very important moral concept, which helped stabilize the society. Men used these expectations of chastity to control women and maintain the social order. Basically they thought that chastity prevented certain uprisings and confusion and chaos and kept the society in order. So a woman’s sexual fidelity represented loyalty not only to her husband, but also to her family and state.

AA: So the next dynasty that we want to talk about is the Tang Dynasty. And the author writes that this is a time where centuries of chaos are being brought to an end. And the Tang, apparently, is kind of a famous dynasty in the popular imagination because it’s a time of rising prosperity and this gave women new opportunities. And the author will of course complicate that narrative by bringing to light kind of the gritty daily reality of actual people. But he writes that overall compared to other periods, Tang women seem to really have been relatively more independent and self-assured compared to other eras.

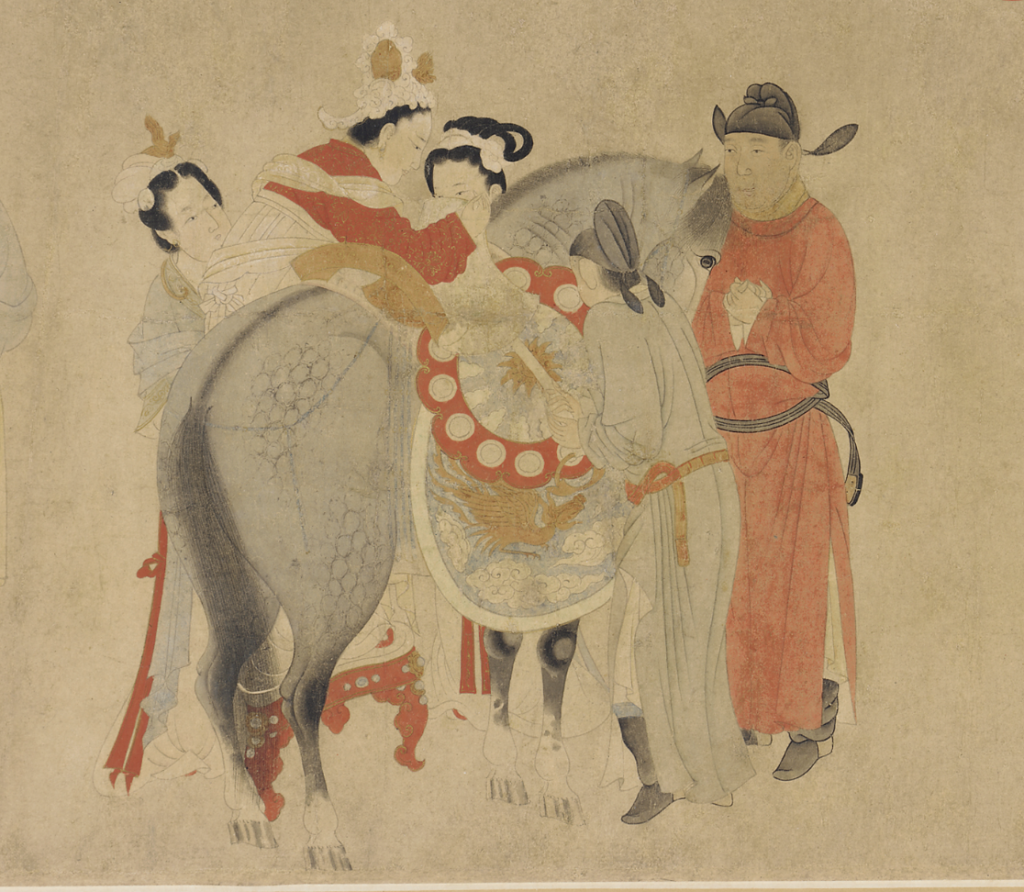

Tang women had a lot of opportunities to go outside the home. There are records of them attending parties with board games and music and poetry. And then again, due to the continuing influence from the north of nomadic cultures, women could even engage in athleticism. They have records of ball games and horseback riding and archery and women hunting. So yeah, this is like a real pendulum swing from eras before. There was one paragraph that was so relatable to me, so I’m going to read it really quick.

It says, “For men, the best life began with years of diligent study followed by a successful career in government. In contrast, society expected women to devote themselves to home and family. According to these accounts, the ideal woman knew how to read and perhaps acquired some high learning, yet she still performed domestic chores and needlework diligently. The proper wife obeyed and supported her husband, made herself amenable to parents-in-law, and bore several children. If she found herself widowed, she declined marriage afterward and dedicated herself to raising and educating her offspring, who rewarded her efforts by becoming successful officials and wives. Although actual lives usually differed considerably, these archetypes reveal what sort of lifestyle would gain public approval.”

That sounded in many ways to me quite similar to kind of the ethos in which I was raised, to be honest, that girls should acquire some high learning, for example, but not too much. And your main job is still to just do domestic chores and take care of your family and be in the house mostly. But yeah, you can have hobbies, it’s great, it’s fine. You can have hobbies, you can have education, lots of greater opportunities. But just to be clear, you really should stay in the home. And also again, this emphasis on your glory comes through your children. That was somewhat relatable to me, to be honest.

One of the most important parts from the Tang Dynasty was the story of Wu Zetian. Could you talk about her, Annabelle?

a woman’s sexual fidelity represented loyalty not only to her husband, but also to her family and state

AQ: Yes, for sure. Yeah, I definitely agree. During this time there were certain aspects of progression, but all of it kind of came back to the idea that the woman should still stay in the house and raise her children. And that’s kind of the most important thing. But Wu Zetian was definitely a contrast to that idea. She was the only woman to rule China in her own name as an emperor. Wu Zetian came from a wealthy family and had a good education, and she was first a concubine to the emperor, but then later went to live in a convent. And then the new emperor, who was the first emperor’s son, brought her back to the palace as a concubine again, and later elevated her to his primary consort. And then as his health declined, she took on more and more responsibilities. Then when he died and his son from another consort became emperor, she disposed of him within a few weeks and made her own son emperor. But she was actually the true ruler of China, even though she wasn’t officially the ruler.

But then six years later, she dethroned her own son and made herself the official emperor of a revived Zhou Dynasty. She ruled with a lot of religious ideology from Buddhism and actually sparked a printing revolution by disseminating Buddhist texts. And then in her old age and illness, her enemy staged a coup and put a man back on the throne and restored the Tang Dynasty. So her rule had a lot of implications for society and for feminism, but most prominently, there arose this idea that women shouldn’t have power at all. And men became increasingly afraid of female power and of another story like that, of a woman taking control. Men became more afraid of female power and decided to try and suppress it.

AA: Yeah, she kept coming up afterwards, she really cast a long shadow. There were some specific things that stood out to me from her reign. One was in the mourning period, so children were required to mourn for their parents after they died and prior to Wu Zetian’s reign, the morning period was three years if your dad died and one year if your mom died. And she changed that and equalized the mourning period so that you mourned three years for either of your parents if they died. And that outlived her reign and became standard practice. One other thing that she did was after her husband’s death, a woman would often manage family property and arrange her children’s marriages. And she just increased the power of mothers, I guess, too. So a woman would essentially act as the head of the household after her husband died instead of turning it over to the son automatically.

So the next dynasty we want to talk about is the Song Dynasty, and that is from 960 to 1279. The author writes: “In many respects, the Song Dynasty marked a major turning point in China’s history. During the Tang era, political power, genealogy, and wealth tended to be interrelated as noble families maintained their status for generations via inheritance. However, in the dynasty’s final decades, this hereditary aristocratic system broke down, unleashing unprecedented dynamism and prosperity. Building on this fundamental transformation during the Song Dynasty, China became the most advanced society that the world had ever seen.”

That’s pretty incredible. “Unlinking status from heredity fostered social mobility and allowed talented people to use their intelligence and skills. The resulting culture of meritocracy shook society to its foundations.”

So that’s just setting the stage for what would happen in the Song Dynasty regarding gender, but I thought that was so interesting just from a sociological perspective, that basically the class system was breaking down. As I read that first paragraph, I thought, okay well then this has to affect women too. And it did. This was a time of flourishing for women. They had substantial independent ownership and control of property, inheritance sometimes passed down to daughters even if the family had sons, and women could keep their property in the case of divorce or widowhood. And that’s a huge contrast to what we talked about earlier. So let’s talk about some marriage customs from the Song Dynasty.

AQ: One important one was about dowry and how that affected women in simultaneously positive and negative ways. Because in some respects, a large salary raised female status within a patriarchal system. And another part of it was that it was technically her money that granted her a higher standing with her in-laws and more independence in the advent of a divorce. So she could go into a marriage with actual property and wealth that was actually hers, and that was definitely a shift from before and spoke to the new independent ownership and control of property that women were starting to have. And that was a big benefit of having a dowry in a marriage.

But there were also problems that arose with the expectation of a dowry. For example, families who couldn’t afford a large dowry for a daughter actually would kill a baby girl instead so that they wouldn’t have to pay her dowry later if she had to get married, because that expectation was just so strong. And that meant that the rate of infanticide increased significantly during this dynasty. And also some women had to wait a long time to marry or could just never marry at all because their families couldn’t afford to give them that high dowry that came to be expected, and that meant that marriages were becoming more about financial transactions than ever before.

AA: The next period was a time of Mongol invasion, and that was the Yuan Dynasty, which was from 1279 to 1368. I mean, this is one of the themes that emerged really from the book was this interplay between the Mongol kind of pastoralists to the north, that had very, very different gender norms, and then the Chinese customs of the South. And during this period, the Mongols invaded again and some of the features of this time of great transition, the chapter is titled “The Great Transition”. The author writes that “the Chinese once again found themselves confronting these alien gender norms.” So these nomadic women from the north rode horses, hunted, and gained renown as warriors. Even after putting down roots in China, wives from these northern peoples initially rejected widow chastity, often either committing suicide upon a husband’s death or undertaking a levirate marriage with one of his kinsmen.

One other interesting piece from this era was that according to one custom, young people could just elope or else a man might forcibly kidnap a bride from her parents. And they allowed a man to kill his wife or concubine with impunity, which from the Chinese perspective, reduced women to a position below slaves. So these are these northern people. In some ways, again, women could ride horses and hunt, but a man could just kidnap a wife and that was fine. And if he didn’t like her, he could kill her. So again, there are certain parts of the culture that really favor women and allow freedom and some that did not.

The other aspect of this era of huge transition and warfare, and this is common across all times and all cultures, is that there women are specifically vulnerable during periods of unrest. And indeed the author writes that many women suffered rape and terrible abuse during this time. And I’m assuming this is because, I mean, the rule of law kind of suffers. There aren’t as many protections, people are in motion, people are coming into communities where they’re not known, and so bad men take advantage of that. And the chastity norms made women feel required to commit suicide rather than endure sexual violence. And so that then became a new important moral archetype. There were women’s biographies actually from the time that idolized these martyrs who decided to die so that they would maintain physical purity. So they were held up as role models, which really shows this oppressive purity culture.

Again, there are no good options for these women. And the next period also is referred to as the “re-Confucianization of law” that after this transition of different cultures colliding and coming together, I guess it’s not surprising that the government would then say, okay we need more structure. And what that meant was Confucianism, that was kind of the traditional structure. And so then that had gender implications and things became a lot more patriarchal again.

So eventually the Mongol government collapsed and a peasant rebellion reunited the realm. And this brought the Yuan Dynasty to an end, and the big transition was over. And they united under the Ming Dynasty, and this was from 1368 to 1644. And this caused rapid economic changes and transformed many aspects of daily life, and created a lot of economic growth and technological advances. And it caused a large number of people to abandon agricultural work and start working for cash wages, like in markets. So the economy really changed and factories emerged. So a lot of modernization during this period.

Another really important thing to note is that there are far more books and paintings that remain from the Ming Dynasty than from all other periods combined. Which as a historian, you just get giddy with excitement, right? There’s tons of material to study from the Ming Dynasty. So Annabelle, do you want to talk about some of the main features of this period of time?

AQ: Yes. Well, we’ve definitely talked about the new Confucian trends that came back and that rhetoric about the separation of the sexes and how we need more laws in order to regulate society. And that kind of resulted in less freedom for women, especially within the household. And one interesting thing was that if a couple had no sons to inherit wealth, the property would go to nephews rather than daughters just to keep that patrilineal bloodline and maintain the patriarchy so that women had a lot less power even compared to before. And another element of that was female seclusion indoors. Because of the new Confucian ideas, women were expected to be confined strictly to the house and all of their activities were based on the domestic sphere. And they weren’t really allowed to leave that or to do other things.

And like that quote we read before about how separate spouses were, that really came back during this time. It says that spouses ate and slept separately and lived separate lives, spent most of the day apart, and the architectural design of their houses even deliberately fostered separation of the sexes so that this certain social order could be maintained. And another idea that was enforced, or reinforced, was the maternal dependence on her relationship with her children. And like we talked about before, a lot of a woman’s power within the house and how she could gain respect came from the accomplishments and the obligations of her children. So she really wanted to reinforce that relationship so that she could have more power in the house because that was kind of the only way to get it. And later, these certain notions and tropes about so-called “hen-pecked husband” and “violent shrew” came up a lot in Ming fiction and literature. And that kind of furthered the notion of this lustful and immoral woman who was jealous of concubines and other women. And that was seen as not virtuous and not moral. So that came back and suppressed the power of women even more by creating these tropes and these archetypes of the immoral and unjust woman.

And then chastity ideology started extending to widows in the Ming and Qing dynasty, even including dismemberment and suicide as punishment or as a result of not following laws of chastity. And I think another big element of that chastity, even for widows, was that even if a husband died, that woman was still said to be the property of his family. So she wasn’t free from him even if he died, because she still had obligations to his parents and to his family. And because that kind of became her family in the marriage and she still belonged to them and was still expected to uphold these laws of chastity and these really strict rules because of her ties to not just him, but all of his family.

…women were expected to be confined strictly to the house and all of their activities were based on the domestic sphere…

AA: Yeah, I know that in the next dynasty we’re going to talk about the Qing Dynasty, but on this topic of widow chastity, if an allegedly chaste widow, we would think of her as single, I guess they didn’t even really think of her as single. He’s dead, but she’s still his wife. If she had a sexual relationship after he died, she was considered to have betrayed her former husband and was guilty of postmortem adultery. I remember that part from that chapter. That is just a completely different way of seeing it, I guess.

So the next dynasty is the Qing Dynasty from 1636 all the way until 1912. So this takes us to the end of the dynastic era in China. It’s obviously a very long period of time, and again, I’ll just read a little bit from the book to set the scene of the Qing Dynasty. It says: “Given China’s immense size, no imperial government could possibly hold together such a vast realm indefinitely. So in spite of its many achievements, the Ming Dynasty eventually came to an ignominious end. In the 17th century, economic crises and famine drove peasants to rebellion. Manchu nomads took advantage of this turmoil to sweep down from the northeast and conquer China, integrating it into a larger Manchu empire under the Qing Dynasty.”

Which again, there are different dates depending on where you look. But mid-1600s to 1912. “After hostilities ceased, Manchus then found themselves living in China as a small minority ruling over a huge and potentially hostile populace.” What were some parts that stood out to you from the Qing Dynasty?

AQ: Well, I think that these two very small ethnic groups, the Manchu and the Han, had very specific gender traditions. For example, Manchu women maintained some traditional customs but they had freedom to move around, to worship at temples, even attend performances. But generally, they still had less education than the Han women and lower literacy rates. And then another part that was interesting was about female reproductive stigma. The female body was viewed as more sickly, contaminated, and unclean, especially during menstruation and after giving birth. And there was this really interesting part where the author talked about that in relation to the yin/yang symbol and how the part that was likened to the woman was seen as less strong. And they interpreted that as how a woman’s body was less clean and less good. And that stigma carried into how women were treated in society and sometimes, like during their times of menstruation, they weren’t allowed into temples to worship because they were seen as unclean. And that was a really interesting part that was really sad to see. Especially taking a symbol like the yin and yang and how that was supposed to represent harmony and balance and how they used that to actually create a hierarchy where women were seen as less than.

So the Qing Dynasty text, Biographies of Exemplary Women by Liu Xiang said that a stable government is formed through harmonious families. It says, “the daughter obeys her parents, the daughter-in-law reverently serves her parents-in-law. The wife assists her husband. The mother guides her sons and daughters. Sisters and sisters-in-law fulfill their appropriate duties.” And then that summarizes the ideology of the Qing dynasty in general.

And then in 1839 the Opium Wars broke out. There was exposure to outside powers and there was a missionary effort to modernize China and gender traditions became symbols of this archaic, backwards China. And there was a lot of internalized Orientalism. The Opium Wars were a really sad time when these outside powers came in and took control over this entire population of people, and that really marked a shift in the ideology and gender traditions. Eventually, reform and revolution led women to be more active in political circles and education. And Western notions of freedom and equality started to take place in China and become integrated into the society and rhetoric. Women had more self-confidence and political awareness, and there was a distinct collapse of traditional values with the Qing Dynasty. And women decided to step up and shape the future of modern China.

AA: And that attitude of women, you know, as we’re getting into the 20th century now we’re entering the era that you’re actually more of an expert in, to be honest, like the end of the dynastic era as a precursor to Mao, right? And how women hold up half the sky and how the Communist Revolution of the 20th century is going to be a huge step toward, at least in theory, should be a step toward egalitarianism. But we’ll talk about that in a future episode when we get into the 20th century. This wraps up our discussion for today. Are there any takeaways that you would like to share at the end here?

AQ: Yes. Well, I just want to first of all say thank you so much for having me. It’s been such an honor to talk about this and to study these texts and to just discuss such important ideas. I just want to say quickly that I feel like studying women’s history and really delving into these concepts that have been studied for centuries, but really like looking at them from a perspective of how they affected women creates this whole new rhetoric and this whole new narrative about what history really is.

I want to say that looking at history from this perspective has helped me so much in enriching my own view of history and about contemporary social issues. And I feel like understanding our history is essential to being able to grow as a society now. And we can see and track this progress of feminism and growth through all of these dynasties up through modern history. And I think that’s really cool to see. Thank you so much for this opportunity.

AA: Annabelle, thank you so much for being here. I am so impressed with the preparation, and everything you brought to this episode was so valuable. I learned so much from you. I learned so much from these books. Really, truly, I started out knowing almost nothing about Chinese history and I learned a lot from the books, but I also learned so much from you and I’m super grateful to the brilliant Annabelle Qian. Thank you for being here today.

AQ: Thank you so much, Amy.

the yin and yang was supposed to represent harmony

…they used that to create a hierarchy

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!