“it only gets better as we learn more”

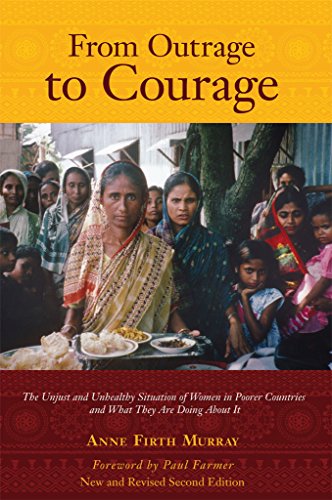

Amy is joined by author, educator, and activist Anne Firth Murray to discuss her book, From Outrage to Courage, and start exploring patriarchy on a global scale.

Our Guest

Anne Firth Murray

Anne Firth Murray, a New Zealander, was educated at the University of California and New York University in economics, political science, and public administration, with a focus on international health policy and women’s reproductive health. She has worked at the United Nations as a writer, taught in Hong Kong and Singapore, and spent several years as an editor with Oxford, Stanford, and Yale University presses. For the past twenty-five years, she has worked in the field of philanthropy, serving as a consultant to many foundations. From 1978 to the end of 1987, she directed the environment and international population programs of the Hewlett Foundation in California. She is the Founding President of The Global Fund for Women, which provides funds internationally to seed, strengthen, and link groups committed to women’s well being. Currently, she is a scholar and activist at the Union Institute and a Consulting Professor in Human Biology at Stanford University. Anne serves on several boards and councils of non-profit organizations, including the African Women’s Development Fund, Commonweal, the Global Justice Center (Chair), GRACE (a group working on HIV/AIDS in East Africa), Hesperian Foundation, and UNNITI (a women’s foundation in India). She is the recipient of many awards and honors for her work on women’s health and philanthropy, and in 2005 she was nominated as one of a group of 1,000 women for the Nobel Peace Prize. Her book, Paradigm Found: Leading and Managing for Positive Change, is available worldwide from bookstores or from the New World Library. Her book on international women’s health, From Outrage to Courage: Women Taking Action for Health and Justice, with a foreword by Paul Farmer, is available worldwide from bookstores or from Common Courage Press.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: One of the things that I really loved about your book is that it is structured around a woman’s life, from the beginning of life to the end of life. And I’d like to structure our conversation in the same way and have you orient us to some of the issues that face women and girls around the world from the beginning of life until the end. So maybe what I can do is summarize the issues that you talk about in each chapter and then we can take a deeper dive on one or two of these issues. If we had hours and hours to talk it would be fascinating to talk about all of them, but I’ll just list some of the ones that you talk about. The very first chapter is “Before birth” and you bring up the fact that sex-selected abortions are an issue in several places in the world. So tell us about sex-selected abortions, why they happen and what it says about the culture where they happen.

Anne Firth Murray: Sex-selective abortion, as the title suggests or even states, is just that. Now that with amniocentesis we can find out what the gender is, what the sex is of a fetus, if people really would rather have a son than a daughter, in some places, they have the capacity to have an abortion to avoid bringing a girl in if they’d rather have a boy. So that’s essentially what that’s about, and of course what it really is about is son preference. And that is not in existence in every country in the world, but probably in most places if people thought they had a choice they would prefer a boy. Now, that’s not always true, I mean in some countries it’s very good to have a girl because as they grow older they are much more likely to be required or even desire to look after their parents or their grandparents or something like that. So it would be considered useful, handy to have an extra girl around. But in general, son preference is the preference.

AA: Moving on to issues of early childhood. Some of the challenges that you write about in the book that face young girls are… there are 5 that you talk about: unequal access to nutrition and healthcare, female genital cutting, lack of access to education, child labor and trafficking, and child marriage. And I have to say as I read each of those chapters, I mean I had heard of these issues and maybe done a little bit of reading on them, but each one of those in turn was so devastating. I would say the one that was most surprising to me, that I hadn’t really been exposed to at all, was the issue of unequal access to nutrition and healthcare. So would you mind talking about that one?

AM: In some countries, maybe even in most countries, if people are faced with a situation where they simply cannot afford to treat all the members of the family equally, if they have to choose to provide basic food to some child, it is more likely to be a boy. It’s just back to this basic son-preference question. And basic discrimination against women and girls. So again, these things are changing, but over time in countries where food is scarce there are large populations of very poor people, people have to make very tough decisions. And those decisions come up to the most basic things, that is who gets fed enough or who gets fed appropriately, and when we get beyond that early age where it’s pretty devastating, if a baby (because it’s female) is not being fed appropriately… I mean the child will probably die. But we see inequities in education as well, access to education.

AA: I’ll say too, I had just finished your class and went on a trip to Vietnam and Cambodia and the tour guide, who was Cambodian, was talking about gender relationships on the tour bus and saying, “here in Cambodia we worship women and husbands just kind of defer to women. The women are the boss of the house and we have goddesses in our traditional religions…” And because I had just taken your class, it wasn’t that I didn’t believe him, I just knew that there was probably more to the story that would complicate that story. We were on our way to a school where we were doing a service project and when we got there, it was an elementary school so like three year-olds through maybe ten year-olds, and I went and was talking with the head of the school and said, “how many of these kids will continue past about fifth grade?” And he said, I don’t remember exactly the numbers, but it was something like 80% of students. And he was really proud of that because that was more than had been in the past– and should be proud of that, that was wonderful. And I said, “how many boys versus girls?” and because I had just taken your class I knew to ask that question. He said, “oh, well, only about 50% of the girls will go on past ten years old.” And that was just a couple of years ago. And like you say, that’s progress. But I just stood there. It was really hard for me because I’d been playing games with these girls and looking at these little faces and thinking, next year they’re not going to go to any more school. They’ll just stay home and help their mothers until they get married in a few years and then have babies for the rest of their lives. So that unequal access to education does determine what your life looks like in a lot of ways.

The other topic under the heading of childhood issues, well all of them struck me so deeply, but one of them that I did a big project on was child marriage. And I just want to recommend to listeners the work of Stephanie Sinclair. She’s a national geographic photographer and she has photographs and stories and interviews in a lot of different publications – National Geographic and the New York Times too – and across multiple countries and in places that I didn’t realize that child marriage happened. I had pictured the Middle East and the subcontinent in Asia, but it happens in Latin America and then as I was doing research, it happens here too. And that was really surprising to me.

AM: Well, it’s regulated. There are laws in various countries about how young and how old a person needs to be before they can be married. But yeah, it certainly happened here and I think part of the confusion here is child marriage– what do we really mean by a child? And I think now that those ages… I think a child can be up to 18, then it’s not quite so shocking. Because we know that lots of people are married before 18, 15-18. But when we think of the numbers of real children, you know under the age of let’s say 15 or 12, it is still shocking to me when people consider forcing them into marriage. Because it’s generally forced marriage at that stage. So yes, it’s shocking and yes it does go on, and I think it continues at very low levels probably in countries like our own, the western democracies and all that. But yes, it certainly happens.

AA: Well, and particularly poignant and sad to me is that when it happens it’s usually fundamentalist religious communities like the Fundamentalist Latter-Day Saint community which is in the state I reside in right now, in Utah, has a problem with that. And so that hits close to home. I would specifically recommend looking up Girls Not Brides and Too Young to Wed– those are two initiatives to end child marriage that are doing really important work. And on the topic of unequal access to education, and did you have any organizations that you want to highlight that are doing work in that space?

AM: It’s constantly amazing to me that women in various countries can come together and actually make such a difference. For example, at the Global Fund for Women we supported organizations like these three that I would like to mention. One new Afghanistan women’s organization works on a lot of different issues but it organizes home-based schools. And even though there’s a great opposition to providing education to girls in parts of Afghanistan, they ran four primary schools. They came and put together primary schools and one hundred girls went to each of these schools. I mean it’s tremendously impressive, and with very little money Global Fund for Women was supporting these organizations. I’m just going to pick a couple out randomly– here’s one in Egypt. We have The Organization of Women and Society founded in Giza in 1994 to address the high level of illiteracy among women in Egypt. And here that’s exactly what we’re talking about. If people don’t get to go to school, they don’t learn how to read and write and they end up as women who are illiterate which makes life very, very difficult in any country in the world now. One last one: in Kenya we have the African Network for the Protection and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. This was created in Nairobi to organize a movement that would go right across Africa to prevent and protect children against all sorts of abuse, including unequal access to education, food, and that sort of thing. So the reason I’d love to have people know more about these groups is that it’s very much a positive direction if we’re thinking of oh, how sad it is that girls are discriminated against. Yes, but women have come together and men have come together to offer all sorts of opportunities for women around the world and it only gets better as we learn more now. So this is the positive side of our work.

It’s constantly amazing to me that women in various countries can come together and actually make such a difference.

AA: And again I love that you structured the book that way, that each section talks about the challenges faced by women in that stage of life and then you end each section with that really uplifting and inspiring information about here’s what local women are already doing and have already made progress to better their own lives. Because so often I feel like we learn about these really, really tragic situations and then we end up just feeling despair and not knowing what we can do to help. And so you can easily look at the book, Google the organization and they’ll have a donate button right there, or whether it’s donating hours of service or money or whatever we have that we can give, that we could actually do something about it. I love that.

Okay, well let’s move on to the next phase of life. You talk about in adulthood, there are several different challenges that you’ve seen around the world that face women. There’s an evocatively-titled chapter called “The Maternal Death Road.” So issues facing women in their reproductive years. And then you talk about gender-based violence, about lack of access to the cash economy, about the impacts of war on women – so vulnerabilities as refugees specifically, which are different vulnerabilities than men face when they find themselves as refugees in war – and then LGBT+ issues and how that impacts adult women throughout the world. So I might like you to talk a little bit about the maternal death road. What does that mean?

AM: In many parts of the world, women get pregnant and they give birth without the kind of support they need to to produce healthy children and to survive childbirth. But the problem there is related very much to what we’re talking about before, which is early marriage. You have children being married, children giving birth, and it’s just plain dangerous. We know that girls need to be at least eighteen or nineteen to be really healthily able to produce children without harming themselves. But when you have little children of fourteen, thirteen getting pregnant, it’s really dangerous. So that’s really what we mean: the maternity death road is getting pregnant when you’re not ready for it and then giving birth in dangerous circumstances. Not having the kind of care that people need and use to get through childbirth safely. But the issue that I would focus on, if we were going to talk about maybe the most difficult or most important or something issue, is violence against women.

Violence is what people produce when they want to maintain their power. And violence in general is hugely widespread in the world everywhere. And violence against women, to my way of thinking, is absolutely the key issue if we’re talking about women’s health. We need to deal with the issue of violence against women. It is very widespread. In many countries, one out of three women will experience violence in at the hands of an intimate partner. In this country it’s about that many. One in four maybe will experience violence. And that’s huge and immensely sad. It’s somebody trying to maintain his position in the hierarchy. And it’s the issue that I think that we should be absolutely putting at the top of our agendas. We need to stop solving our problems by using violence at every level. We think of… spanking kids when they’re bad. You know, hurting them, using violence, and giving them the example of violence as a way of solving a problem. It’s dangerous and it’s wrongheaded to continue to make use of violence of all kinds to try to solve our problems, whether it goes from just a person hitting a child because the child has been naughty or something, to war.

AA: That speaks so much to how we as human beings grow up thinking whatever we’ve witnessed in childhood is normal, right? And so if violence is the way we solve problems and assert authority, like you say, or teach somebody something, then that’s what we think is normal. And that brings to mind the topic specifically of sexual violence. And I remember hearing a piece that they were doing on NPR on the radio, and I was sitting in the Target parking lot and was so horrified but so engrossed in this story, I just stayed in my car listening to it. There had been a gang rape in India that had happened a few years prior, and they were interviewing one of the men who had who had perpetrated this horrible crime against this girl. And he had been a teenage boy at the time and they were interviewing this man who had done this, and he truly sounded really sincere that he said, “I did not realize it was hurting her.” And it was so incomprehensible to me, but he said some other things too that really reflected that he hadn’t been taught that a girl was a human being with her own thoughts, and that she had her own reality, and that she didn’t exist as just a female body for his physical pleasure. That she didn’t exist for him. And it struck me and I’ve remembered it forever because I thought, oh, he grew up with this whole different set of expectations of what a girl was in the world. And so it brings to mind how essential it is to teach girls differently about who they are, but also to teach boys differently about who girls are.

AM: Yeah, we have pretty clear ideas handed down to us about what a girl can do and what she can’t do, and that sort of thing. I remember many times in my very happy household, my brother had a paper route and he was able to make some money. And I said, “I want to have a paper route!” My brother was older, four years older, and my mother just said, “oh no, you can’t, you’re a girl.” And she was right because they never hired girls to have paper routes. It was always the boys. So there were these little things where oh you can’t do that because you’re a girl. And not only would I come to the conclusion that oh I guess I can’t do that because I’m a girl, but my brother then knew well, you can’t do that, you’re a girl. You know, it was so basic. All sorts of things. And again I had a very happy household with parents that treated each other beautifully and in very nice ways. I grew up in a very happy and quiet– a nonviolent household except if you were naughty you could get spanked. And my brother certainly was able to do things that I wanted to do that I couldn’t do because I was a girl that still goes on. But don’t you think it’s changing? I really do think it is in most countries.

…violence against women, to my way of thinking, is absolutely the key issue if we’re talking about women’s health…

AA: Yeah.

AM: And surprisingly, if you think of a country like India where there are so many examples of outrageous discrimination against women… but it’s a country where women have been the head of state several times. And so it’s sort of confusing. What’s going on here?

AA: Isn’t that the truth. And lest we get too arrogant and proud of ourselves in the United States, I do reflect on that often when I’m reading about other countries and thinking oh that’s so terrible and then I think, yes, but they’ve had a female prime minister several times. I was just talking with a Liberian friend and she was reminding me that Liberia elected a woman president in the early 2000s and that still hasn’t happened here. So yeah, all over the world. We’re still in these piecemeal efforts just doing our best to try to move the needle and move things along in our different ways with these different challenges. So could you talk a little bit about some of the local initiatives again that are trying to address this problem?

AM: Okay, if we’re talking about violence I think it’s absolutely at the center. If we’re thinking about women’s health one has to focus in on violence. A couple of examples of organizations, and these are local organizations, in the countries that I’ll name that are working on this issue and I’ve always been absolutely amazed by what the women are able to do at the local level. One is Cameroon, in Africa. Women in Action against Gender Based Violence and that’s a group that was founded a while ago. It promotes a culture of peace, social justice, and legal empowerment for women and girls. And it participates in radio programs and TV programs and that sort of thing to push that agenda, and they are looking specifically at violence against women. There’s a group in Brazil called Sepia; it’s a research and policy group based in Rio de Janeiro. It’s dedicated to implementing projects that promote human rights especially among groups historically excluded from exercising their full rights, obviously women. And many of these organizations that are listed in my book were supported by the Global Fund for Women, not all of them but many of them were. And we ended up really identifying our interests basically as women’s rights being human rights. There are many more; I was continually inspired by finding that there were hundreds of women’s groups, two or three women coming together and making change everywhere. It was really, really inspiring.

AA: How did you find these women’s groups, by the way? I mean, are some of them groups that you found on the ground when you were visiting these countries with the Global Fund for Women or just people you knew? How did you find all these amazing people?

AM: You know, that always surprised me. We started the Global Fund for Women with the idea that we’d raise money to give away money to women’s groups that worked on behalf of the human rights of women. So we set it up. So everyone thought oh, the hardest part about this is going to be to raise the money, but it certainly ended up not being that. First of all, it was a popular thing for people to do. They wanted to help women’s groups. And so we just put the word out among our friends – and there are three or four women who are at the beginning of the Global Fund for Women who had worked internationally and I had worked internationally for years, and then we got in touch with places like Planned Parenthood, that works internationally. And I think I gave a presentation or was speaking to a group of people from the Peace Corps and pretty soon we were inundated with requests from various organizations because the kids in the Peace Corps told local women’s organizations that we existed. And all of a sudden we were hearing from people all over the place. I would say probably the individual members of the Peace Corps got interested in what we were doing and told local groups to write to us and probably helped those little local groups write to us. Our grants were small at the beginning, maybe up to $10,000 and then they went up to $15k a little later. The organization has grown hugely over time.

AA: Oh that’s fantastic, it’s done so much good. And I also think of, of course, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and especially the work they’re doing providing contraception and teaching about contraception. We can’t really talk about adult women’s lives without talking about the importance of access to contraception. Let’s move along to the last phase of life and we’ll talk about the last part of the book which talks about aging. And some of the challenges that face aging women globally. And you talk about in the book the feminization of poverty and how that manifests specifically in the later years of life, and then about the health consequences of a lifetime of work.

AM: I’m in the last phase of life, I guess. Hard to imagine or to realize actually… And I think back on my mother, who when she was my age, which is mid-80s, she and I would talk – she was in New Zealand and we’d talk by phone – and she’d tell me about her friends and what had happened. One time I was talking with her and she was saying oh, Olive got sick and she had to go to the hospital, and so-and-so was sick. So I said mom, how are you because your friends all seem to be getting sick. And she said, well I’m okay, I’m fine. She was very healthy until she died, and she died at the age I am right now. Anyway, she said this is the hardest time of life. I said, well why is that? Why do you think it’s the hardest time of life? And she said, because it’s a time of constant loss. You’re losing your friends, you’re losing your family, you’re losing your sight or you’re hearing, you’re losing the ability to or the opportunities to do all kinds of things. I mean, there are things I used to like to do that I can’t do now and I think to myself, yeah, she’s quite right. I was just speaking to somebody about going to an event this weekend and this friend of mine is coming, and she’s much younger than I am, she’s coming to give me a ride. Because we’d be coming back from the party at night and I don’t think I should be driving at night. I think I’m a good driver but… so you lose these things. It’s a time of loss now. I think there was a time when age, just by virtue of being old, commanded respect. I think some people feel that way, but that has also been lost to a huge degree I think. And internationally for women, being an old woman in many countries is a situation where you’re respected, but less and less so. It’s just you’re old, and it’s hard, and it’s a time of loss.

AA: I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about that topic that I mentioned: the health consequences of a lifetime of work, specifically sometimes in other countries where women are really relegated to the home and caretaking for their entire lives.

AM: Well yeah, there’s a little section in my book called that. And so maybe just reading it will be clearer. The health consequences of a lifetime of work… The economic, social, and political inequalities that women face throughout their lifetimes are magnified in old age. And many older women in poorer countries live in chronic ill health, according to the World Health Organization. For example, poverty at older ages often reflects poor economic status early in life, and is a determinant of health at all stages of life. Countries that have data on poverty by age and sex, mostly the developed countries, show that older women are more likely to be poor than older men. Well that shouldn’t be too surprising, I mean our own experience and just observing, we would know that. The WHO reports that poverty is also linked to inadequate access to food and nutrition. And that’s really interesting I think. And the health of older women often reflects this cumulative impact of poor diets. And yeah, we know that older women – if we even think of older women we may know or older women as we read – that they will hold back and not eat in order to allow children to eat. I mean, this has been going on for years. They will limit themselves for the children particularly. So here we are, years of childbearing, heavy physical labor, and sacrificing her own nutrition to that of her family, leaves the older woman with chronic anemia and general malnutrition.

AA: So were there any organizations or local initiatives that are aimed to combat those problems for aging women?

AM: Yeah, there are some. But when I was writing the book I wanted to find examples, good examples of women’s groups that were working on women as they aged. And it was really very difficult and in fact, now even looking at my book, it reminds me that I put in as examples women’s groups that were working on a variety of issues relating to women but not necessarily older women. It was very hard to find. Here’s one that does look at older women and that is in Nigeria, the Widows Development Organization. And that organization was established in Eastern Nigeria. They wanted to sensitize the general public to the plight of widows in Nigeria and bring about social change in traditional customs affecting them, create awareness about the rights of widows, and provide counseling and support for widows, and develop collaborations with other organizations, and so on. So there’s one; they were looking specifically at widows, presumably fairly old women. And one could go through, I don’t know how many, maybe ten examples here. And we might find a couple that will focus on aging but not many more than that.

…years of childbearing, heavy physical labor, and sacrificing her own nutrition to that of her family, leaves the older woman with chronic anemia and general malnutrition.

AA: That is so interesting and it does speak to what you said at the beginning, that perhaps in that age bracket, things might be in some ways getting worse than they used to be. And we are living longer than we used to as a whole species, notwithstanding the different life expectancies in different countries. On the whole we’re living longer so we will spend more time in the elderly phase of our lives. So it’s a real shame that we’re not getting more support and more care for the elderly, right? And especially women.

AM: Women live longer than men in general. And I don’t know, it’s very hard and kind of dangerous to generalize about these things. It depends on where you are. I mean, I think that women, as we’re growing older, are now becoming more active outside of their families. Obviously they’ve been active in their families, but women live longer than men and they’re taking action on all kinds of issues, organizing themselves. But my experience in writing the book about women in different ages was that I found very few organizations that were dedicated directly to older women.

AA: Well that wraps up our discussion of the book, and I just want to end the conversation today by asking you if you have advice. Because this is the introductory episode of the whole season that we’re going to be talking about lots of different global issues for girls and women and marginalized genders all over the world… And specifically for listeners who are maybe new to these topics, and for listeners who are white and Western and maybe haven’t had hands-on on the ground experience in a lot of these countries, I think a lot about the pitfalls and the dangers of looking at a different culture without a real nuanced understanding of it. And the dangers of being patronizing or having a white savior complex as we look at other countries. And, you know, we are feeling solidarity and we’re feeling compassion, but how would you advise me and maybe our listeners in this undertaking of looking at global issues for women?

AM: Well I do have some ideas about it. I think what comes to mind first is, as we’re going out there trying to learn about the world, and trying to change the world, trying to make the world a better place and all of that… I think our basic mode should be learning. We don’t have the answers. We have some answers that might fit us but we don’t have the answers. So, my feeling about– and I’ve felt this way for all my life but certainly since working actively internationally, you just go with an open mind to see if you can learn from whomever you’re talking with in whatever country. What can we learn? And they’ll be wanting to learn from you and from us. But we must go with that totally open mind, with the concept, with the conviction that we do not know as much as they do. I mean, there’s just no question about it. Anyone logically would say, how can I know more than a peasant woman in Kenya knows about her life? She knows about her life. So we must learn. That’s overarching my message. So many organizations from the West with people going out with really good intentions, they may make more trouble than they solve, but maybe they’re okay and they put some money out there or something. But for the most part, I think that the field of international relations– people in the West and America and Western Europe honestly believe that they have the answers. And it’s absolutely wrong. I mean, we just must be in a learning mode. And especially now as people are communicating widely around the world. I mean these people living in different countries are not just out there isolated. They’re watching the kinds of TV that we might be watching. They’re listening to programs that we can listen to. People are learning from each other at the moment, but we have to learn from them. So that’s my major offering and I really mean it strongly.

AA: Well thank you so very much, I’m so grateful for this conversation. So wonderful to see you again, and you’re a hero to me and I’m so grateful to have you as a friend and a mentor and thank you for this conversation today.

AM: Oh thank you, Amy, I hope I can live up to all of that! Many thanks. It’s wonderful to hear after a few years from a student, somebody who was in my class. That’s really exciting to me. Thank you.

People are learning from each other at the moment,

but we have to learn from them.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!