“art was made by men and for men”

Amy is joined by Dr. Danielle Stewart to discuss Linda Nochlin’s essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, and examine the historical and contemporary hurdles faced by women artists.

Our Guest

Dr. Danielle Stewart

Danielle Stewart is an art historian who specializes in the modern and contemporary art of the Americas. Her most recent publications investigate how mid-century Brazilian photography and popular media, especially illustrated magazines, helped to shape regional, national, and personal identities. Born and raised near San Francisco, California, educated in Utah, and a longtime resident of Harlem, New York, Danielle has also lived in Curitiba, Brazil, and Coventry in the United Kingdom. This broad range of environments fundamentally informs Danielle’s research.

Danielle completed her Masters of Philosophy and PhD in Art History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and her BA and MA degrees at Brigham Young University. From 2019 to 2020, Danielle was a fellow in the Princeton Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism, and the Humanities and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. From 2020-2023, she held the position of Assistant Professor of Latin American Art at the University of Warwick in the UK. Danielle has also held curatorial positions at the BYU Museum of Art and the Mount Vernon Hotel Museum in New York City. Her writing has appeared in publications sponsored by the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in Brazil, the Instituto Moreira Salles, the Fundación Cisneros, and La Universidad de los Andes, the College Art Association, the Latin American Studies Association, and The Space Between society.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Throughout all three seasons of the podcast, we have periodically referred to fine art as a touchstone of culture that reveals the values of the society that produced the art, but we’ve never dedicated an entire episode to patriarchal constructs in the world of art and art history and art criticism. And today I am so excited to dig into these topics with art history professor, Dr. Danielle Stewart. Welcome, Danielle.

Dr. Danielle Stewart: Hi, Amy. Thanks so much for having me here. I’m a big listener of your podcasts and I’m really excited to do this episode with you.

AA: I’m really excited to have you here.

This has been fun. We’ve been in contact, I feel like, for probably more than a year, kind of batting around ideas. And this episode… it’s so fun that it’ll fit in at the end of the season where we’re talking about miscellaneous subjects in European history. And I’m so excited to be able to talk about art because, like I said, it just keeps coming up and it’s such an important topic, so this is super exciting.

We always start with a bio and I’ll read your professional bio, and then if there’s anything you want to add about your personal story, you can.

DS: Great. Thanks.

AA: Danielle Stewart is an art historian who specializes in the modern and contemporary art of the Americas. Her most recent publications investigate how mid-century Brazilian photography and popular media, especially illustrated magazines, helped to shape regional, national, and personal identities. Born and raised near San Francisco, California, educated in Utah, and a longtime resident of Harlem, New York, Danielle has also lived in Curitiba, Brazil, and Coventry in the United Kingdom. This broad range of environments fundamentally informs Danielle’s research.

Danielle completed her Masters of Philosophy and PhD in Art History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and her BA and MA degrees at Brigham Young University. From 2019 to 2020, Danielle was a fellow in the Princeton Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism, and the Humanities and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. From 2020-2023, she held the position of Assistant Professor of Latin American Art at the University of Warwick in the UK. Danielle has also held curatorial positions at the BYU Museum of Art and the Mount Vernon Hotel Museum in New York City. Her writing has appeared in publications sponsored by the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in Brazil, the Instituto Moreira Salles, the Fundación Cisneros, and La Universidad de los Andes, the College Art Association, the Latin American Studies Association, and The Space Between society.

That is awesome, Danielle. That’s a really impressive amount of stuff you’ve done.

DS: Us academics like to flaunt our publications, but yeah, it’s been an exciting couple of years.

AA: You’ve made some really impressive contributions and that’s so cool.

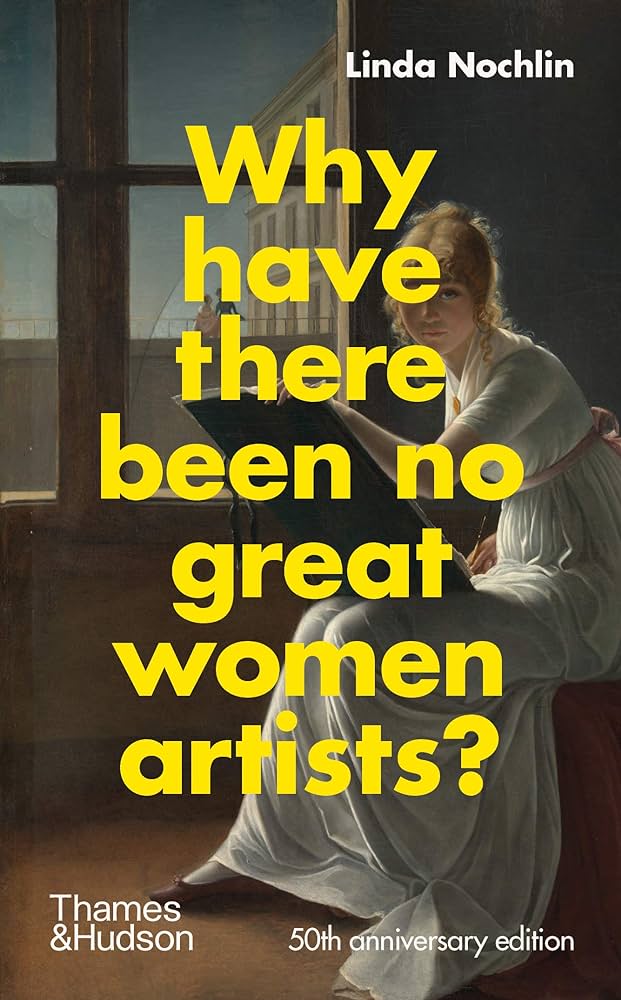

So we’re going to approach this topic through an essential essay in feminist art criticism, which is called ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’ by Linda Nochlin. And she wrote this essay in 1971. And Danielle, you’re the one who showed me this essay and kind of chose it for the topic of the podcast so I’d love it if you could start us off by telling us a little bit about this author, Linda Nochlin.

DS: Yeah. So when I suggested it I didn’t realize that the essay is almost, well, it’s over 50 years old now. But it really is sort of the foundational forerunner text in terms of feminist art criticism and so it’s still so important and still so relevant and I really look forward to discussing it.

Linda Nochlin was one of the greatest art historians, maybe ever, but definitely of the 20th century. So just a little bit of background on her: She was born in 1931, and she was raised in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, in this neighborhood that was historically divided between the Jewish and African American communities. Her family was secular, leftist, Jewish, fairly wealthy, and they really prioritized intellectual achievement, social justice, and the arts—and we see that come out really prominently in her work. She really had this, what I think is an idyllic childhood. She describes going to institutions like the Cloisters Museum on Sunday to go to their classical music concerts and to the Brooklyn Public Library and to City Center to see dancing (That is kind of the childhood that I wish that I had had). She received her BA in Philosophy from Vassar College in 1951, and then an MA in English from Columbia in 1952, and finally her PhD in Art History from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University in 1963. And especially kind of in the 1960s, seventies, and eighties, The Institute of Fine Arts was really an institution that was putting out landmark publications and doing a lot of cutting-edge art history. So, you know, she’s going to the top schools here.

She taught at various institutions in the New York City area, and she became a renowned scholar of French 19th-century art and was also one of the leading voices of second wave feminism in academia, and that really comes out through this article that we are going to talk about. And it’s important to note that this article was originally printed not in kind of like a stuffy academic journal, but it was printed in the art news magazine, which was… I mean, it’s still directed towards people who are interested in the arts world, but it’s much more kind of popularly accessible, right? So she wasn’t just imagining this as an essay only that would go out to academic peers, but that would have some kind of broad, more popular appeal. She also curated multiple shows of feminist art, including ‘Women Artists, 1550-1950’. This was the first international exhibition solely of female artists, and that opened at the L.A. County Museum of Art on December 21st, 1976.

Then she expanded that in a show called ‘Global Feminisms’ that opened at the Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum in New York City in 2007 and that included 88 women artists from around the world. So, I know your podcast, you’ve thought a lot about feminism and intersectional feminism and how to make feminism open to a broader, cross-section of women rather than just kind of upper class white women—and that’s something that I think Linda Nochlin was really at the forefront of, and that even comes out in this essay from 1971 that we’re going to talk about.

I also wanted to point out that another way that we see this is that in addition to this essay, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’, which is probably her most famous work, maybe her second most famous essay is one called ‘The Imaginary Orient’ that she published in 1983, and that really exposed how 19th-century French artists made these prejudicial depictions of Middle Eastern peoples, and it’s kind of the ethnic prejudice and Orientalism that went into those depictions. So she’s really tuned into these issues of racial and ethnic prejudice, as well as prejudice against women. And she passed away, unfortunately, in 2017 at the age of 86, but she really was a giant in the field of art history and maybe one of the most important voices for her generation of academics, so it’s an honor just to be talking about her work.

AA: This is amazing. Just once again, I’m having this experience of thinking, why had I never read this before? And honestly, Orientalism was something that was quite new to me just in this last series of this last season of the podcast, so to know that there was this essay that already existed in 1983 and that she was… you know, all of this stuff has been said before, it just really reinforces, again, the importance of bringing these into public discourse so that people can benefit from them earlier in their lives. I’m so grateful for her work and so grateful to you for showing this to me and highlighting it today, Danielle. This is awesome.

And kind of speaking of that, I guess what I keep saying to myself is like better late than never, right? I mean, I’m in my forties. I’m just discovering all of these important essential foundational texts and I had this experience again with this essay when I looked at the title and saw ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ and I was like, Oh, Oh, I have new information! I have other texts that I can bring into the conversation already, honestly, because of this education project that I’ve been doing for the past few years. I wouldn’t have had that before, you know, even a few years ago. Immediately when I read this question in the title, “why have there been no great women artists?” I thought, Oh, I know what Mary Wollstonecraft would say about that. I know what John Stuart Mill would have said about that, and Virginia Woolf…And if I were teaching a class, the first thing I would do is ask students to write what they would guess that each of these thinkers would have answered to why have there been no great women artists?

And then sure enough, I start reading the essay and Nochlin opens her essay with kind of a concept that I learned from Simone de Beauvoir. Nochlin says, “in the field of art history, the white Western male viewpoint is unconsciously accepted as the viewpoint of the art historian.” So, essentially, that’s Beauvoir, to me at least. Beauvoir pointed out that we live in a world where men are the main characters. A man is the primary person, the person who is the agent, the person who does the looking and the acting. And the woman is the secondary person, the one who gets looked at and is acted upon. And this is manifest all over the world of art. Right, Danielle?

DS: Yeah, definitely. I also clued into some things early in this essay that reminded me of texts that you clued me into through this podcast. So for example, I read The Creation of Patriarchy last year after hearing about it here, and that was really an eye-opening text to me and I had the same thought: why have I never heard of this text before? You know, I’ve read ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ I’ve done some feminist art history, but I think we’re all learning, and so it’s important that we meet each other where we are.

I think in the world of art also, there’s this problem where male audiences have been the traditional audience and, in part, that’s because male audiences have been the ones that have had the money to participate in the art world, to buy the artworks, to write the art criticism. And we see increasingly, even in the modern era, that men were the ones who had the ability to circulate in public so they could go out to art shows. You know, now, of course we can circulate freely; women can go out in public, women can shop, and women can walk the streets. But in the 19th-century, that wasn’t true. Women, especially kind of upper-class women, were mostly confined to their homes. To go out in public was really the man’s world. So art was made by men and for men. The women’s point of view was really not taken into consideration. It was very difficult for women artists to participate in the art world. And even when they did participate in the art world, they weren’t usually painting the kind of scenes that male audiences wanted to see because they weren’t objectifying women in the same ways.

We sometimes tend to think about the art world as kind of high-minded and quasi-spiritual and about this kind of sense of self-expression. But we also need to realize that the art world is about material, physical things, and that artists make money and that it’s driven oftentimes by the consumers and what they want to buy—and so often what the people have wanted to buy has been art that objectifies women, and that’s because the primary audience was male. We see even today, in a time when women are participating more in the art world as artists, as art historians, as art critics, still the top earning contemporary artists tend to be men.

I just looked up this information for the podcast, and as of 2021, of the top 120 most expensive paintings ever purchased, none of them were by female artists, even though art schools reached gender parity in terms of enrollment in 1983. So we really need to think about how our artistic circuits, like museums and galleries and art fairs, and even maybe the art memes that we see on the internet or the art posters that we buy to put on our college dorm room… how those are really biased towards male-oriented vision and towards male creators.

AA: Wow. That’s really striking. Well, like you said, this essay was written in 1971 and maybe they’re like…I thought as I read it, there are kind of a couple phrases that dated it just a little bit where I was like, okay, I can tell this was a few decades ago, but it seems that almost everything in it is still, sadly, super relevant. I mean, to that point that you just said, if gender parity was reached in 1983 in art school and yet we’re still seeing these discrepancies, then yeah, sadly, this is still very much an issue.

So I wrote down some questions for you, Danielle, you being the expert on this topic and having, again, shared this article with me. Maybe I’ll just bring up topic by topic and then you can respond if that’s okay?

DS: Yeah. Yeah. Great.

AA: So, Nochlin poses the question right at the very beginning of the essay that she obviously gets a lot: if women really are equal to men, then why have there been no great women artists or composers or mathematicians or philosophers, right?

so often what the people have wanted to buy has been art that objectifies women, and that’s because the primary audience was male

And I have to throw in, too, I still get this question sometimes and Jordan Peterson has famously said that women have not been historically oppressed and that the differences we see are due to aptitude and women’s choices. And so again, I just feel like this is still relevant. It still comes up in my life. And Nochlin points out that implied in this question is already the answer: there haven’t been any great women artists because women are incapable of greatness.

DS: Yeah. So I think what we see unraveling through the course of this essay is that Nochlin is really trying to show us how our concept of ‘greatness’ is really underlaid by a fundamentally male-oriented perspective. And this has to do a little bit about what I was talking about before; that men were the art critics, the art dealers, the art purchasers. So when we think about what ‘great art’ is, very often the elements that make great art are stories or narratives that include a vision of women that makes them very passive and makes them the subject of the painting rather than unique individuals with their own perspective.

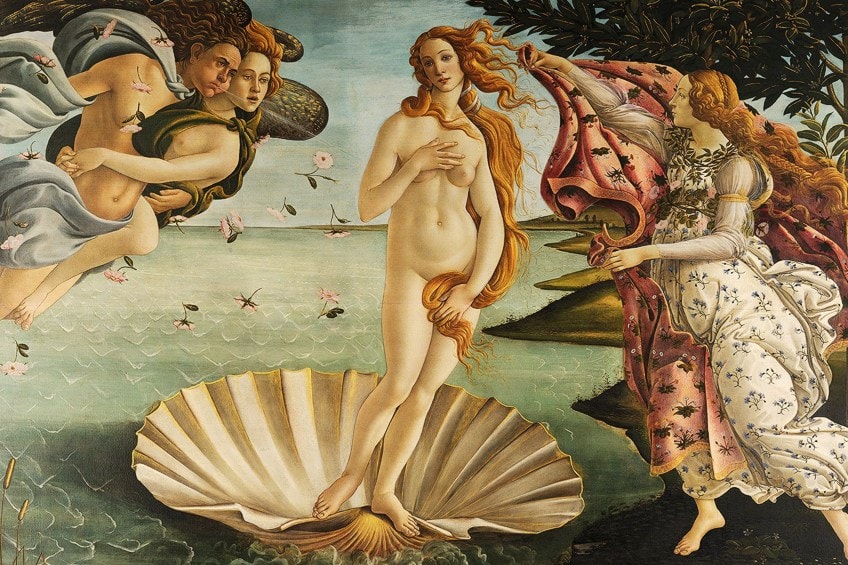

One way we see this play out is when you think about ‘great art’. A lot of the great art that we think about includes nudes of females, right? And its art that is intentionally created to be somewhat sexualized, somewhat provocative, even if we think about the classical paintings from the Renaissance. Lots of people like to think that they’re all completely high-minded, and that there’s no sexual subtext there. There is! Those were paintings of women that were meant to look desirable, and they were meant to… right?! So a lot of the problem is that our concept of what great art is, is tied up in a masculine perspective.

But then another thing that Nochlin wants to show us is that a lot of the institutions that breed art, especially in the 19th-century, in the early 20th-century, were completely biased against women. So they didn’t have the same educational opportunities or they didn’t have the same opportunities to circulate in public that men did, and therefore their ability to develop their skills was just very limited. So what Nochlin’s argument really comes back to is it’s the systems that we are embedded in that impede the progress of a female artist. And that’s a little bit less true today, but like I said, we see that our art institutions are really still dominated by male voices and by male leadership.

AA: Yeah, for sure. I appreciate, also, I think this essay was really useful in that there were some soundbites in there that I felt like I could kind of tuck into my pocket and have ready as references for when tricky conversations come up in day to day life. And she does address this, like, when we’re confronted with this challenge of, “There haven’t been any great women artists or scientists or whatever, X, Y, Z, because women are incapable of greatness.” Why haven’t there been? It’s like this challenge and it does come up sometimes. And I appreciated that she said, you might be tempted to say this, but don’t because of this. And one that I wanted to highlight from the beginning of the essay is she says this: “The feminist’s first reaction is to swallow the bait, hook, line and sinker, and to attempt to answer the question as it is put: that is, to dig up examples of worthy or insufficiently appreciated women artists throughout history…to “rediscover” forgotten flower painters or David followers and make out a case for them”. And she says that that’s the wrong approach. She says, they do nothing to question the assumptions lying behind the question “Why have there been no great women artists?” On the contrary, by attempting to answer it, they tacitly reinforce its negative implications.” So I thought that was fantastic. She says don’t take the bait. You have to, like you just said, Danielle… it’s the wrong question to ask.

And then she points out another way that women sometimes answer the question. She says another attempt to answer this question involves “shifting the ground slightly and asserting, as some contemporary feminists do, that there is a different kind of “greatness” for women’s art than for men’s, thereby postulating the existence of a distinctive and recognizable feminine style, different both in its formal and its expressive qualities and based on the special character of women’s situation and experience.” What did you think about this, Danielle?

DS: Yeah, this is really tricky because I think in both cases, in response to both of the quotes that you just read, it’s kind of a both/and situation. I think in one sense, we do need to dig up those great women artists, because there are really fabulous, great women artists that have been overlooked by history for a variety of reasons (we’ll talk about some of those as we go along). On the other hand, we also need to be looking at the systems and the institutions and the problems with those and how they were biased against women.

In response to this latter part, when she says, “postulating the existence of a distinctive feminine style”…I think on the one hand, she says in her essay that female artists are closer to their male contemporaries in whichever period they were in than they are to other women artists throughout the years. And this is true, right? We see female Impressionist artists that are painting like male Impressionist artists, and we see female Color Field painters that are painting like male Color Field painters. And at the same time, we also see that there are certain subjects or certain narratives that come up that are part of female experience, right? That maybe don’t reflect the same tropes or the same ideas or the same themes as male experience, because women have had different experiences because of the way they were acculturated, right? Women have had more caring responsibilities—and this is something that’s come up on your podcast: that we don’t give enough attention, or we don’t give enough of a prioritization to those caring responsibilities—we also see that female painters tend to depict those things with greater frequency than male painters.

So in some ways, I think that it’s kind of this both/and that we need to do all of this work. I think that we’ve seen that from Feminist art historians over the course of the last fifty years since Nochlin wrote this essay, but one example of how this plays out in terms of making the art world a less hospitable place for women in the 18th– to the 19th-centuries—which is when Nochlin is an expert and when she’s kind of focusing the majority of this particular argument, when she talks about why have there been no great women artists, a lot of her argumentation comes back to the 18th and 19th centuries—there was what was called the hierarchy of genres. So different kinds of paintings had different cultural value. And the hierarchy was:

At the top were what was called history painting, and those were paintings of wars or paintings of kings and queens, biblical stories, and myths. These things that kind of had these grandiose narratives around them, and those are the histories that we would see in history books. Those are also the histories in which we tend to see men primarily participating as the protagonists in terms of those written narratives and those written myths, right? If you think about the Bible, there’s just not that many women. So if you’re doing mostly biblical scenes, you’re not going to be showing that many women, right? Or if you’re painting wars, again, not that many women. Or if you’re painting kings, you might have the queen, but she’s going to be sort of in the background, right? These are paintings that foreground men.

After history painting, there was portraiture and then genre painting, which tended to be more household scenes or peasant scenes. And this was an area where women excelled and where they were more represented because they did do a lot of household scenes because that was the milieu that they were in, that was the environment that they had to paint. But even if you were the best genre painter in a particular show, you’re still coming in sort of in third place, according to this hierarchy of genres. After that was landscapes and still life’s, and those were other genres that women were more encouraged to paint. Even when they did have art education, they were kind of encouraged to paint in these three lower categories of genre, landscape, and still life.

So they never really had the opportunity to become history painters. It required a lot of training. It required that you make trips to Rome and to Greece to paint in front of old historic buildings, and women couldn’t do those things. They were just not allowed. And it also required huge studios where you commanded troops of painters who painted the backgrounds of the paintings and helped you fill in the little details, right? The big history painters weren’t painting these scenes all by themselves. They usually had assistants and women also couldn’t do that. They couldn’t run their own studio. That would have been a scene that’s improper for them. So even the best women painters, like I’m saying, they’re already coming in at a disadvantage. And this is one of the ways that we see patriarchy really pushing women out of those top master spots within the art world.

AA: Okay, that was so fabulous.

I guess maybe just to summarize one of her first main points as you said Danielle, and I love the nuance that you brought to it because she’s maybe perhaps a little more blunt in saying “the fact of the matter is that there have been no supremely great women artists as far as we know although there have been many interesting and very good ones who remain insufficiently investigated or appreciated.” I want to highlight kind of the next point that she makes, which is she says, “nor have there been any great Lithuanian jazz pianists, nor Eskimo tennis players, (we would say Inuit now) no matter how much we might wish there had been.” And so in saying this, she’s kind of pointing out the essence of one of her main arguments, which is if you don’t have the opportunity to develop a skill, then how would you develop that skill? And then to be blamed that you can’t when you don’t have access, right? Not being able to develop it. And I do want to throw in this quote as well: she says, “in actuality, as we all know, things as they are and as they have been, in the arts as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive, and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class, and above all, male. The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education—education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals. The miracle is, in fact, that given the overwhelming against women, or blacks, that so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence, in those bailiwicks of white masculine prerogative like science, politics, or the arts.”

we see patriarchy really pushing women out of those top master spots within the art world

DS: This is one place where I maybe differ a little bit from Linda Nochlin. Like you said, she’s very blunt when she says that there have been no supremely great women artists, and I think that we’ve seen the art world change enough in the last 50 years that we’ve stopped talking a little bit about this idea of greatness or masterpieces and started thinking about art more in terms of how famous it is, maybe, instead of what a masterpiece it is.

I mean, I still do think that as art historians there’s some works that we just value, that we find really beautiful, but I think as the art world has become more global, as we’ve started to look at artworks that are outside of Europe and America, into Latin America, into different cultural traditions in the global South, that we have stopped kind of thinking about art as ‘supremely great’ versus ‘not as great’, and instead seeing all art production as just evidence of the cultural milieu that it was created in. I think that’s really important in this particular case because I think it allows for us to see these women as really excellent artists that are, on the scale of Michelangelo or that are on the scale of someone like Picasso, because they were able to achieve so much with such little access.

For me, that’s a much more hopeful way of thinking about art production than trying to say, you know, why isn’t a woman like Michelangelo? Well, a woman is not like Michelangelo because she doesn’t have that kind of fame because we haven’t traditionally prioritized her. It’s not necessarily because she’s not as good technically. It’s because she hasn’t been given the attention of scholars and of critics and of the populace. If we all started to go see Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes, like we all now go see the Mona Lisa, that would now become the new masterpiece. It is just as good as the Mona Lisa; it’s just that it’s not as famous as the Mona Lisa. And why is it not as famous? Because patriarchy.

AA: Thank you for pointing that out. That’s so important.

Okay, the next topic that I wanted to highlight from this essay is, again, this is where Nochlin is saying, okay, so an argument might be this. Here’s how we’re going to answer this question. And again, super useful because these are still things that come up. So she addresses the argument that many men are also denied opportunity. Which of course is true, right? And so how does she address this issue, Danielle?

DS: Yeah, it is true that men’s choices are also limited at times. And she brings up a really good point that most men that become famous artists have some other artist or artistic professional in their family, right? So very often this is an issue of opportunity, but she says that no men are denied the ability to become an artist simply because they are men. So she sums it up really well and she says, one has only to think of Delacroix, Corbet, Degas, Van Gogh, and Toulouse-Lautrec (these are really well-known artists’ names) as examples of great artists who gave up the distractions and obligations of family life, at least in part, so they could pursue their artistic careers more single mindedly. So she talks about men. They also have to make sacrifices. They also have to pursue their careers single mindedly. Yet, none of them was automatically denied the pleasure of sex or companionship on account of this choice, nor did they ever conceive that they had sacrificed their manhood or their sexual role on account of their single mindedness in achieving professional fulfillment. But if the artist in question were to be a woman, 1,000 years of guilt, self-doubt, and objecthood would have added to the undeniable difficulties of being an artist in the modern world.

So she says, of course men make sacrifices. Of course it’s not always easy for them. Of course the men with greater access to the art world are going to become better artists, but they don’t have to deal with the guilt, the self-doubt, the objecthood or with the impediments of not being able to go in public, or as she talks about later, women not having the same access to education that men did.

AA: I think this is so important. This is something that I really got from Virginia Woolf and loved to see here in this context, is Again, coming back to that fact that you shared that there have been technically the same number of women enrolled in art programs as men since 1983. And so then you can imagine the argument being like, “well, see, you do have equal access to education, so it must be just an aptitude issue.” And I love that she brings up those internal barriers—guilt, doubt, and being objectified—and all of those things that are harder to quantify, but they are so real in the mind of any woman.

The scene that comes to my mind is from To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, where Lily Briscoe is the character and she’s doing plein air painting, and she loves art, she loves to paint, she’s really good, but she just describes that as she’s painting, she just has this voice in her head of the men through her life that say “Women can’t paint. Women aren’t painters. Women aren’t artists.” And she battles with these internal demons. Well, how do you quantify that? You’re not going to see that on a data sheet about technically their access to education, but it’s still really hard when you’re recovering from the residue of all of these systems that have been in place for hundreds or thousands of years.

DS: Yeah. and these are internal and external difficulties. I know that you’ve, like I said, talked about on your podcast the fact that women still on average do more care work, even in situations where both they and their partners are working, so it’s also this matter of just sort of the practical issues of women’s lives that they’ve had to be in places where they could put down their own work and do the care work of their families. And that historically hasn’t been something that’s been expected of men; maybe on an individual basis, but not by and at large.

AA: Yeah, totally. And even that part that you just read from her where, I mean, the men were making sacrifices for their art, but women weren’t allowed to even make those sacrifices, right? A man could say, “I’m sacrificing time with my family to go develop my career.” Well, a woman can’t make that sacrifice of abandoning the kids and not doing the laundry or making the food, right? They literally can’t.

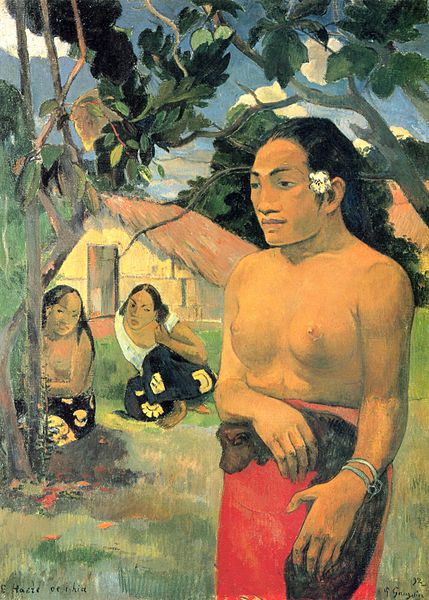

DS: Yeah, and I think the best example of that is one of the artists that she mentions in her essay is Gauguin who’s a very famous modernist artist and in order for Gauguin to become who he was, he abandoned his family—his wife and his children—left them behind and went off to Polynesia to kind of discover himself and paint among the Polynesians. And even while he was there, he sexually took advantage of many young women and was having extramarital affairs and then writing to his wife about it. His wife couldn’t abandon her family responsibility, especially not once her husband was gone. So in many cases, it was almost a prerequisite that the women had to take care of their families while these male artists were out honing their craft.

Painting and being an artist, both today and in the past, requires a lot of travel, going to art fairs, showing your work, traveling abroad to paint and sketch. This wasn’t an easy profession. It did require sacrifices of men, but those sacrifices usually put more care work on the women in their lives. And for women, certainly, it was almost impossible to find a woman whose family was supportive enough that they would allow her to do that. And even if they didn’t travel, for example, even women artists who kind of worked in domestic spaces and did local landscapes or local depictions of people that they knew, it was still very difficult to find the time to get access to the materials, to have the education. And then when they completed those paintings, their paintings were not seen as as valuable because they weren’t as exotic or they didn’t depict far off places, right? So there was a sense within modernist art, and this is something that another really influential female art historian, Griselda Pollock talks about that women often painted domestic spaces cause that’s what they had access to, but those weren’t prioritized. Those weren’t prized. And so they didn’t become as famous. And so they don’t have the notoriety now that these male artists do. And it’s because nobody wanted to see domestic scenes, that just wasn’t as cool as pictures of Tahiti. And still today, we don’t think it’s as cool to see a picture of a mother and child as to see a painting of Tahiti that still draws audiences.

AA: Okay, one of her next arguments is the ‘golden nugget of genius’ argument. Could you tell us about that, Danielle?

DS: Yeah, this is so difficult. I think even now if you just take a second and imagine genius, someone who’s a genius in your mind, I think that 99 percent of listeners would think of someone who’s male, right? Maybe someone like Albert Einstein and. Especially after Nochlin publishes this, there’s really this recognition that genius is sort of this coded-male word, and this comes out of kind of the long history of the way that we write history and in art history, one of the earliest art historians is an Italian man named Giorgio Vasari, and he writes this book called The Lives of the Artists, and in his writing about artist biographies he talks about a lot of these artists as being sort of like these pastoral farmers and shepherds that just had this spark of genius within them, that nothing could contain and that they had to find their way into greatness. And there’s almost like this quasi-religious, biblical savior narrative that Giorgio Vasari—who again is in Italian writing during the Renaissance, so he’s permeated with biblical ideas—gives to these artists of them being kind of these saviors of art. But our religious stories are mostly male and our art stories are mostly male and so it becomes this kind of expectation that the genius figure is a male figure, right? And we don’t call females geniuses all that often. So this is a kind of terminology that, especially after this essay, art history really swerved away from.

We don’t think about and we don’t write about artists as being geniuses and we don’t write about works very often as being masterpieces anymore because those words don’t really say anything and because they’ve become coded with these sort of male stories. So when we look back to someone like Vasari, he does recognize that many artists came from places that weren’t privileged or that they had to overcome certain obstacles, but he also recognizes that many artists also came out of artistic families. And this is something that we mentioned before briefly, and it’s something that frankly is still a problem today. I know that I opened up my computer the other day and there was kind of an internet fear because a recent celebrity had been wearing a shirt that said ‘Nepo-baby’ across the front. It was acknowledging that her fame and her celebrity came from her family line. We see some of this in art history as well, that there are certain artists who are kind of these ‘touched geniuses’ where their inner spark could not be suppressed but then, for the most part, most artists are coming out of a context where their family has some sort of artistic background. And that is really what fosters their creativity at a really young age, right? So it’s not so much that they’re geniuses, it’s that they have exposure to art from being in utero essentially. And that really builds up this wealth of experience, which they’re then able to exploit and develop in adulthood.

AA: Totally. That was so interesting. That was a point that I really wouldn’t have thought of in the essay. She says that, in reality, because artists come disproportionately from artist fathers, she says another question, a more fruitful question to ask might be, ‘why have there been no great artists from the aristocracy?’ She says, “Is it not that the kinds of demands and expectations placed before both aristocrats and women, the amount of time necessarily devoted to social functions, the very kinds of activities demanded simply made total devotion to profession out of the question, indeed unthinkable, both for upper-class males and for women generally, rather than it being a question of genius and talent.” I had never thought of that before, that even upper-class males, I guess what she’s saying is like, they’re kind of too busy and have too many obligations to be able to spend their time in the craft.

So I thought that was interesting. What did you think, Danielle?

DS: Yeah, this goes back to the point earlier about kind of being able to devote yourself really wholeheartedly to the occupation of art, which artists have to do in order to become kind of famous in order to be at the top of their craft and this part of the essay actually was really difficult for me on a personal level because I think it speaks so directly to my own experience. And so if you’ll indulge me a little bit, I just want to tell a little bit of my story.

I was raised with the explicit expectation that I would not pursue a career, like many women who come out of conservative religious cultures. I was told that I was to be a homemaker and that that was my great calling in life and that my husband would provide for me. And even when I asked people around me how much money would I need to make in the future to buy a home, for example, people would tell me, “Oh, you don’t need to worry about that. Your husband will worry about that.” And when I was sent to college, I was kind of explicitly told that this education was an opportunity for me to meet a husband. And that the education was what I was doing while I waited to meet a husband. And I’m not making fun of or disparaging homemaking at all. My mother was a homemaker and she was brilliant and she was fabulous, and she did so many just really hard things. I don’t think her work in any way has been acknowledged or recognized just how hard of a worker she was, but for me, it was difficult because I really loved to study, and I wanted to go receive an education for an education’s sake. And I was really kind of professionally motivated and it was just really excruciating for me to feel this tension of knowing that at any point I might have to give that up. That the major that I picked… I had to pick something that would allow me to set it down and walk away if I needed to, or if I got married, if I had a child and that if I did pursue any sort of professional training it was going to be a profession that I had to be ready to put down at any point.

This really limited my abilities and my opportunities because I felt like I could never devote too much time or attention to any sort of education or professional goals because I always had to be ready to walk away. And I was always kind of developing kind of my homemaking skills alongside of my education, right? So as I was pursuing education, I was also learning to quilt and to sew and to cook and do all these other things, dedicating my time to kind of this other part of me that I was also expected to develop.

I think fortunately I didn’t meet someone right away in college. I didn’t meet someone actually until my first year of my PhD program. And by that point I had kind of gotten the fortitude to say, “I’m not going to put this down. I’m going to go through and I’m going to finish my PhD.” And my partner was very, very supportive. And there were times after I had both of my children when I thought this is too much, I can’t do it all at the same time. I’m going to quit. And he never let me quit. And now I’m kind of working in the profession that I chose. And I really enjoy my professional life, but it has been hard. I have felt the weight of those caregiving responsibilities as has my partner and there were lots of things that I had to give up and that I couldn’t pursue, that I couldn’t kind of apply for grants or for fellowships or for travel opportunities because I did have children, right?

So this tension of always having your attention divided between two things, of never allowing yourself to kind of fully commit to one path, that really does limit a person’s ability and their potential growth. I think this is something that we still see today for many women, that they just don’t feel like they can commit themselves totally because of the caregiving responsibilities that they’re also expected to come up with. And I think also this portion though, kind of on a happier note, it also reminds me of kind of one of my favorite stories in art history which is a place where the exception sort of proves the rule and just to kind of plug women artists and to resurrect some of these stories that we don’t hear that often, I wanted to talk a little bit about Lilly Martin Spencer.

She was a U. S. artist in the 1850s and she was the most famous probably genre painter of her day. And again, going back to the hierarchy of genres, right? She’s painting in that kind of middle category where she isn’t going to get huge fame, but she was fairly commercially successful and she actually became the breadwinner for her entire family. She had 13 children, seven of which made it to adulthood. I don’t know how she did that cause I only have two and I’m exhausted. And her husband sort of became her manager. So again, partly her success is due to the fact that it seems like she had a very supportive home life when it came to her painting. But the scenes that she painted, again, were more domestic scenes based on her experience. When she wanted to paint a person, she either modeled herself for the image or had her husband model, right? So she had to kind of work within a little bit more of a constricted environment. And she painted scenes like, The Young Husband, First Marketing, which is this really funny scene. It’s in the Met Museum of a man in 1950s suit who has a straw basket with food that’s spilling out of it. And he’s gone to the market to do the shopping for his wife, but he hasn’t quite known what to buy and so it’s kind of this hodgepodge, just like a pineapple and a chicken and some eggs that are falling out of the basket.

So she paints these really funny, really endearing scenes. She’s very successful in her day. Nobody really knows about her now, and it’s because she was a genre painter and because as a woman, her story just hasn’t been as prioritized. And so I think this is another example of an artist who really was excellent, and perhaps if we prioritized caregiving and domestic stories more, she would be as famous as some of the male artists like Van Gogh or Gauguin, whose names we know. But those just haven’t been the stories that we’ve been as interested in telling, right?

AA: Exactly. I’m so glad you brought her to our attention. I’m going to look her up after we finish recording. That’s awesome. Thank you so much.

So, one of the next points that we wanted to highlight from the essay was that Nochlin points out that even in past centuries, kind of like today—I mean, this feels like what it is now, too—girls are encouraged to do art in childhood. And I feel like sometimes more girls are encouraged to do art than boys. Like boys are sometimes even discouraged from doing art. However, there comes a point in adulthood where the boys seem to surpass the girls. And Nochlin points out some of the concrete reasons why. Do you want to talk about those, Danielle?

DS: Yeah, a lot of these had to do with institutions, especially around education. And that’s something that we see today and one thing I want to say is I think that especially in the United States, these sort of gender prejudices around who gets to do art are stronger than they are even in contemporary Europe. I don’t think there’s quite as much prejudice against men being artists or art historians or not men, but boys kind of dabbling in these fields as there is in the United States. But the big problem for girls was just kind of the lack of education once you got into the higher orders of art production. So we see this, especially in somewhere like France in the 19th-century, the French Academy de Beaux Arts was the school to study in. It was the place that turned out all the most famous artists in the global North, in the Western hemisphere, but women were not allowed in the Academy de Beaux Arts. If you got in, it was free. They had prizes like the Prix de Rome, where if you won it you could go to Rome on a government grant and live in Rome and sketch in Rome. That was not available to women. So women, if they wanted to become artists, they could not enroll in the top art schools. They did not have access to the top professors. They didn’t have access to the travel and the scholarships and prizes that men did. They had to pay out of pocket for small private art academies that were usually quite expensive. So you had to either be a woman of a certain class that would have access to money, but then your social limitations would make it more difficult for you to become a practicing artist. Or, for women of the lower social classes, it was more feasible or more plausible for them, socially speaking, to enroll in an art academy, but they didn’t usually have the money to do so. So it becomes a sort of double-bind for female artists.

AA: One other interesting thing that I had never encountered before was she talks about a cultural insistence upon a modest, proficient, self-demeaning level of amateurism as a suitable accomplishment for the well brought up young woman. And I thought that was fascinating. I guess I’ve noticed that kind of anecdotally, and I’ve even talked about that with other women of like…you’re supposed to dabble and kind of like be a well-rounded and I mean, if you think of Jane Austen novels or whatever; being confined to the parlor, but you’re supposed to be good enough at piano, be good enough at needlework or whatever, and be able to hold a good enough conversation that people find you interesting, but she points out that you’re really discouraged from excelling really in any one thing. And that was just more clearly articulated than I had heard before, that it reached a certain point and then it became a liability, not an asset to be brilliant in any one thing.

if we prioritized caregiving and domestic stories more, she would be as famous as some of the male artists

DS: Yeah, and this is really a problem for women, especially those who want to be artists. Modesty is not, generally speaking, an advantage for artists. If you want to be an artist, you have to be able to show your work. You have to be able to exhibit your work. You have to be able to self-promote to some extent. You have to put your work into shows and get judgments back about it. So this idea of women being able to do things kind of tolerably well or modestly, but not too well really is a liability for people who want to go into the arts where there’s a lot of self-promotion involved.

And then I think just modesty generally is a problem for women in the 19th-century because being an artist meant that you had to be in places where there was some degree of exposure or some degree of maybe immodesty, especially because art production in the 19th-century, very often included sketching from live models and that was something again, that was not available to women. Still today in art school, one of the most important early exercises is to sketch from the nude, right? And that was seen as just completely anathema to being a modest young woman, to be in a room with a naked person, be that a male or a female. So that was another way in which education was very limited for female students.

AA: Yeah, she talks about it specifically that. She says “as late as 1893, lady students were not admitted to life drawing at the Royal Academy in London.” And even when they were after that date, the model had to be partially draped, which she says would be “like a medical student being denied the opportunity to dissect or even examine the naked human body.” And so that was a huge disadvantage for women to not be able to draw nudes, but what women would do instead is like lower class women might be able to get a job being the model, posing in the nude. So this leads us to the bigger topic of the male gaze. A bunch of men looking at a partially clad or completely naked woman. Can you talk about that, Danielle? This is a big topic.

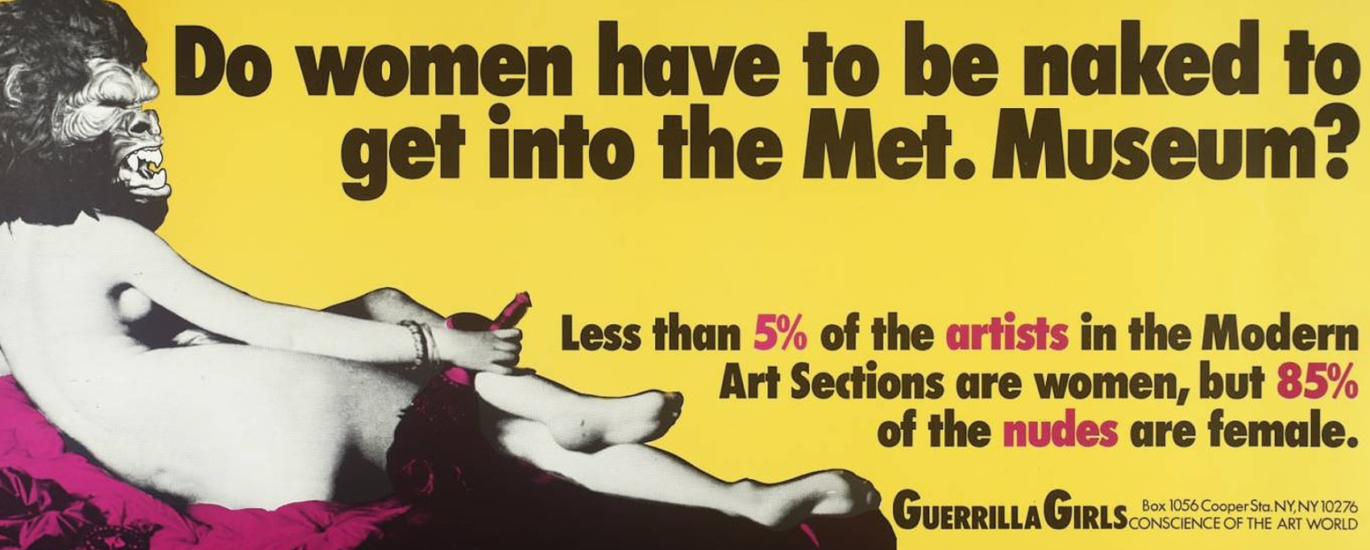

DS: Yeah, this is a big topic and this goes back to this idea of what do we want to see when we want to see art? And so often the artworks that we think of as valuable or famous include nudes. That’s been a real big part of the art tradition, and I don’t want to condemn all nudes as bad—that’s not what I think at all—but I do think that there’s an element of those nudes that responds to, in a certain sense, sexual desire and that assumes a male audience. And I think the place where this comes out most clearly is in a group of work, a body of work that’s been created by a collective of female artists that go by the name of the Guerrilla Girls.

So these are anonymous women, there’s usually five in the group, and I think that they rotate, but nobody knows their identities for sure, so we can’t say. I’ve actually thought that maybe Linda Nochlin was one at one time, but that’s just a guess. So this was a kind of collective that was formed in New York City in 1985 to protest the prejudice against women in the art world and the lack of women artists in really important museum shows. Specifically, they were responding to an exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art that was called ‘An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture’ that had 165 artists included and only 13 were women. And the curator famously said that any artists not in the show should rethink ‘his career’ as though all artists were male. So they joined together and they decide they’re going to use guerrilla tactics to fight sexism in the art world. And kind of as a funny thing as well they wear gorilla masks whenever they make public appearances. So they’re the Guerrilla Girls with a ‘ue’, but they also wear gorilla masks.

One of their most famous campaigns is that they took this image of a painter named Jean Dominique Ingres, his image called The Grand Odalisque, which is this kind of reclining nude. She’s very famous because she has kind of this very long back and torso. I mean, she’s anatomically stretched. No women look like this in real life. So they took this image of The Grand Odalisque and they put it on a billboard with a phrase that said, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the modern arts section are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.” So we really need to think about this. if we’re at a place where we have nudes of both genders, but 85% are female, right? That really shows us how much the art world is catering to this eroticized male gaze, and especially when there’s so little representation by female artists. This is a project that they’ve carried on for several years.

So they go back periodically and they review the collection a few years later that they found out that fewer nudes were female, only about 83%. But there were also fewer female artists on display, only 3%. So I don’t know, we’re getting better and worse at the same time. And what’s really ironic is that they post these posters and advertisements on billboards and in really public places to provoke conversation and to make people think about sexism; one of the places that they place these advertisements in the first round was they put them on the side of New York City buses and almost immediately they were taken down because they were seen as too distracting and too erotic and that they were not kind of suitable for public view.

So here we have, again, this idea that these nudes are okay to see in a gallery context, but not on the street. And it really shows you the way that sometimes I think we’ve whitewashed art a little bit by thinking that it’s high-minded and it’s a celebration of beauty when really there is a part of art that’s responding to a very male-coded form of desire and that’s objectifying women in a very essentializing way.

AA: And it’s unbelievable to me too that it was only when the art was used to draw attention to the sexism that it was criticized as being sexual. It’s crazy.

DS: Yeah. That’s the great irony of it. And I think that we see that with a lot of female artists that they kind of refuse to objectify women or they draw attention to the male gaze. They draw attention to the way that men look at women in objectifying ways and those kinds of artworks often receive more pushback than the original nudes or the original objectifying artwork in the first place.

So a really great example of this is that in 1863 in France, they had The Salon, which was this kind of famous art show that they had every other year, I believe, where they put kind of all of the most famous paintings or all the best paintings that have been created that year on display. In 1863, it was important because that year they had this just overwhelming number of depictions of Venus, the goddess Venus, and Venus is always shown as this very beautiful, but very naked woman, right? And the king of France, or I guess the emperor at the time, Napoleon III, just sort of came in and bought up a bunch of these pieces for his personal collection, including one that’s a very sexualized image by an artist named Alexandre Cabanel, which is now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris—which is one of the two most kind of famous art museums in Paris, and so it’s still kind of this prize of the Musée d’Orsay collection. Well, that year also, Manet, the artist, painted another nude female called The Luncheon on the Grass. And in this Luncheon on the Grass, instead of the nude being kind of a person from the mythological past who is flirting seductively with the viewer, The Luncheon on the Grass shows a nude female just looking directly at the audience, looking directly at whoever’s approaching the painting in this almost accusatory way, and that painting was rejected and that Manet painting, it was shown actually in a separate room called the ‘Salon of the Rejects’ because it was judged to be not up to standard, whereas this other more sexualized female, more flirtatious female was bought by Napoleon III, right? So very often these paintings that bring us into confrontation with the idea of the male gaze are the ones that are rejected or the ones that are not given as much cultural prominence.

Of course, the irony is that now The Luncheon on the Grass is by far the more famous painting because it did set off this set of recognition. Whereas Cabanel is… it’s still a very famous painting, like I said, it’s in the Musée d’Orsay, but it’s kind of not as well known as Manet.

AA: That’s fascinating. I do know that Manet painting, but I didn’t know that piece of its history.

So we’re almost to the end. What are some other topics from this essay and from patriarchy and art history that you wanted to talk about, Danielle?

DS: I mean, I think I just want to draw attention to some of the ways that art history has changed since Nochlin wrote this essay and some of the ways that it’s still the same so we can think about both the progress that we’ve made and some of the ways that we can continue to make progress.

these paintings that bring us into confrontation with the idea of the male gaze are the ones that are rejected or the ones that are not given as much cultural prominence.

So there’s a quote that I want to read here, kind of a paragraph that comes towards the end of the essay, where Nochlin really sums up her arguments that I think wraps everything up really nicely. She says, “The question “Why have there been no great women artists?” has led us to the conclusion, so far, that art is not a free, autonomous activity of a super endowed individual, “influenced” by previous artists, and more vaguely and superficially, by “social forces,” but, rather, that the total situation of art making, both in terms of the development of the art maker and in the nature and quality of the work of art itself, occur in a social situation, are integral elements of this social structure, and are mediated and determined by specific and definable social institutions, be they art academies, systems of patronage, mythologies of the divine creator, artist as he-man or social outcast.”

I think for me, the key here is that she says that art is really mediated by social institutions, right? And those social institutions are really what’s either preserving the patriarchy or helping to break it down. And so I just wanted to give our audience kind of a sense of some of what these art institutions are in our world today. Some of the biggest ones are museums and galleries and then another kind of big art institution is academia, the work I’m engaged with and how we present art curriculum to our students. So kind of a breakdown here: in September of 2019, the New York Times ran an article actually about the status of women in the art world, and they gave us a sense of kind of how women are doing now, and how many shows that they’re receiving at major institutions, and whether their work is being collected or not so I wanted to share some of the data from their findings. As of 2019, they said in the last decade only 11% of art collected by major museums was made by women, just 29,000 works by female artists were acquired by the 26 art museums of the United States out of a total of 260,000 works. Of roughly 6,000 female artists whose works were acquired, 190 women, or just 3%, were African American. So we have a problem here, not only of a gender division, but of racial divisions. And as you’ve brought up before, it’s even harder to be a Black woman or an Asian woman or a Hispanic woman than it is to be a white woman in our current cultural climate.

According to the researcher’s dataset, the number of acquisitions of artworks by women peaked in 2009, actually. So we’ve been going slightly downhill since 2009. From 2008 to 2018, according to their data, 14% of all exhibitions were either solo shows featuring female artists or group exhibitions, in which the majority of artists were female. So only 14% of all major exhibitions were female-oriented or female-dominant. The art market is another major institution, and they found that from 2008 to 2018, the market for art by women grew, but it only accounted for 2% of the total market share. And of that share, five female artists dominate the market, so the majority is going to the small group of artists, and they were accounted for 41% of total sales and they were Yayoi Kusama, Joan Mitchell, Louise Bourgeois, Giorgio O’Keefe, and Agnes Martin. And only Ms. Kusama is living now, right? So both our museums and our market are skewed still drastically towards men. And one of the major issues that’s come up here is that a lot of collectors are still men, and very often those collectors are giving their collections to the museum. So even if a museum wants to acquire more work by females, they’re very often kind of constrained by the gifts that they’re receiving.

The other thing that’s really important to note, and I think this is something that my own profession needs to do better at, is how we write and publish about women. It’s important to know that the first art history survey text, the major kind of survey text for the United States, was written by a woman. It was written by Helen Gardner in 1926. Unfortunately, she did not write about any female artists, they didn’t appear in her main text until 1948, which was several editions later. And this just kind of kills me, that as a female that she didn’t find it useful to include other female artists. That’s really heartbreaking. And I think later in 1999, another woman wrote the other kind of major survey texts that’s used sometimes now, it was Marilyn Stock and she did include far more female artists and this is really kind of important to me and I would hope that we would see more examples of women art historians writing about women artists and taking time to think about their histories.

AA: Oh, that’s fascinating. Well, I wish we could talk longer about this, but is there any last takeaway or final quote that you want to share with listeners before we wrap up, Danielle?

DS: Yeah, I think. It can be hard of hard to read Nochlin’s essay sometimes because it’s really heartbreaking to have condensed into such a short form all of the difficulties and all of the obstacles that women historically had to face to make it into the art world.

There’s a certain heaviness to it, but I love that Linda Nochlin doesn’t let that get her down. She ends the essay on this really empowering note and so I want to read her final words because I think that those are really important for the listeners to keep in mind as they go about doing their own work of breaking down patriarchy.

Nochlin says, “What is important is that women face up to the reality of their history and of their present situation, without making excuses or puffing mediocrity. Disadvantage may indeed be an excuse; it is not, however, an intellectual position. Rather, using as a vantage point their situation as underdogs in the realm of grandeur, and outsiders in that ideology, women can reveal institutional and intellectual weaknesses in general, and at the same time that they destroy false consciousness, take part in the creation of institutions in which clear thought–and true greatness–are challenges open to anyone, man or woman, courageous enough to take the necessary risk, the leap into the unknown.”

I just love that. That energizes me. I love this idea that we can create new institutions. I think that that’s really important to think that we, like she says, “honestly face up to our history”, that we learn it. You know, we both talked about how there’s been so much that we haven’t known and that we’ve found ourself discovering later in life, right? And so it’s really my hope that I can pass on some of this history to my daughters, that they don’t have to learn it when they’re 40 years old and that they can be invested in the institutions that support anyone, regardless of gender, that allow greatness and intellectual curiosity to rise to the top, rather than having blockades set up that are based on things like gender bias.

AA: Here, here. What a beautiful and inspiring way to close out the episode. Thank you so much, Danielle. Thanks for sharing your expertise. I’ve learned so much from this essay and from you and really enjoyed our conversation today. Thanks so much for being here.

DS: Thank you, Amy. It was a pleasure.

The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces,

but in our institutions and our education

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!