“you might call yourself middle class but you’re still a worker”

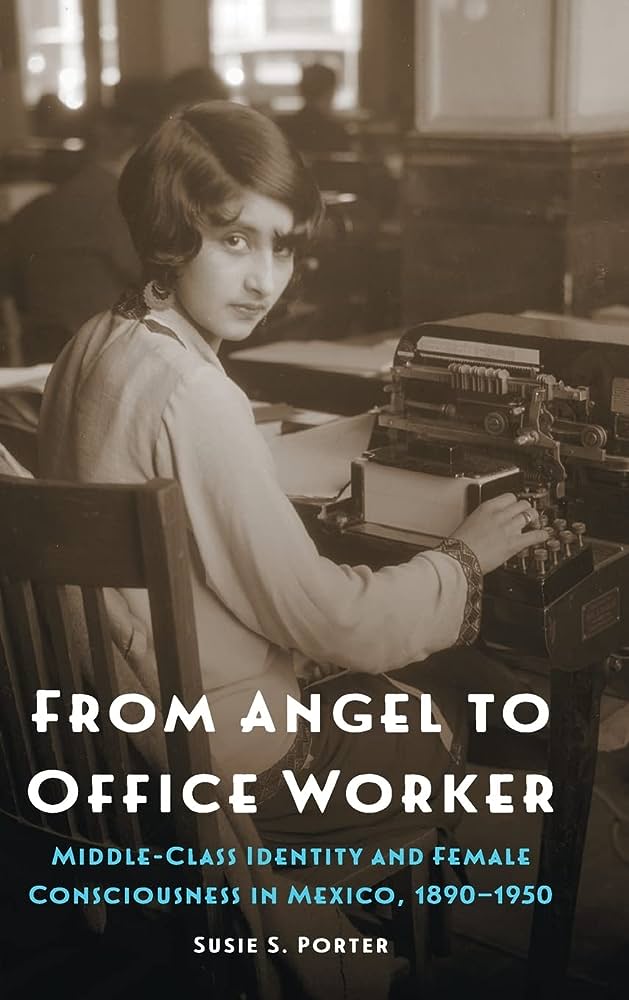

Amy is joined by Dr. Susie Porter to discuss her book From Angel to Office Worker and explore the nuances of class, gender, and labor in Mexico.

Our Guest

Dr. Susie Porter

Dr. Susie Porter is a Presidential Societal Impact Scholar and Distinguished Professor in the Humanities. She serves as a country conditions expert for asylum cases, was a founder of the Westside Leadership Institute (Spanish language version), and works as an organizer with the Salt Lake City Latinx community. She served as Chair of the Gender Studies Division (2010-2020) and, since 2021, as Director of the Center for Latin American Studies.

Porter is the author of two award-winning books: Workingwomen in Mexico City (Arizona, 2003); and From Angel to Office Worker: Middle-Class Identity and Female Consciousness in Mexico, 1890-1950 (Nebraska, 2018)-both also published by El Colegio de Michoacán press. Porter is co-editor of Orden social e identidad de género, with María Teresa Fernández Aceves and Carmen Ramos Escandón (2006); and, Género en la encrucijada de la historia social y cultural, with Fernández Aceves (2015).

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Long-time podcast listeners will remember an episode from Season One where we read and analyzed a 19th-century British poem by Coventry Patmore called “The Angel in the House”. This poem both reflected and promoted the cult of domesticity that confined women to the work of the home, prohibiting them from participating in the workforce, in politics, in religious leadership, or anything else that was in the public realm. We talked about ways in which the separate spheres ideology restricted Victorian women in England and in the United States, but I didn’t know until now that this phenomenon affected other countries as well. Today we’ll be discussing the book From Angel to Office Worker: Middle Class Identity and Female Consciousness in Mexico, 1890-1950 by Dr. Susie Porter. And I was really surprised to learn that the angel that’s referred to in the title of the book came from the ideology of el angel del hogar, which means the angel of the home, which haunted Latin America too. So From Angel to Office Worker covers this process whereby women entered the workforce in Mexico, and it’s a fascinating history that I’m so excited to discuss with the author of the book, Dr. Susie Porter. Welcome, Susie!

Dr. Susie Porter: Thanks for having me here, Amy.

AA: I’m so excited to have you, and I am wondering if you can start us off by telling us a little bit about you, both your professional life and your personal life. Where you’re from and what has led you to do the work that you do.

SP: Sure. I was born in Watsonville, California, I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. My interest in labor history comes from my parents’ work. My mom was a secretary, my father worked in a wide range of jobs, construction, as a gardener sometimes, he had a restaurant that failed, lots of occupations. That experience shaped my ideas about class, and we can talk about that later. I went to UC Berkeley as an undergraduate and I had no idea what history was as a discipline or political science as a discipline or any of that. So I ended up being a Latin American studies major because it allowed me to learn about Latin America by reading literature and poetry and learning about politics and economics. So I really appreciated that interdisciplinarity. And then I went to UC San Diego and got a PhD in history and Latin American history. And I started at the University of Utah in 1996, and I have been here ever since.

AA: Fabulous. What classes do you teach there at the university?

SP: I’m in the history department and the gender studies program. So I teach a survey of Latin America, I teach Mexican history, I teach a course on gender and power in Latin America. And I’ve also taught intro to women’s studies, intro to gender studies, courses on contemporary issues, those kinds of things.

AA: Fabulous. So what brought you to this really specific topic of From Angel to Office Worker, this time and this place in Mexico for your book?

SP: Yeah, I mean, in a general sense I became interested in the topic of secretaries because my mom worked as a secretary. I always wanted to figure out where she went when she went to work and all these little notes and shorthand that she would have in her purse. And so I was always fascinated by that work. What does it mean to be a secretary? But I also became interested in this topic because when I went to graduate school, labor history was really important and I’m very interested in work and questions of class. My first book was about the role of women in early industrialization in Mexico in the late 19th, early 20th century. So when I went to the archives and I wanted to write a book on working women, I would come across, you know, you go through dirty boxes of old papers and publications and you’re trying to find information about the past. And I would find things and I would think, “Hmm, vendors, is that working class or not working class?… Women who work in textile factories. Okay, that’s typically working class.” And then I found information on secretaries and I thought, “No, they’re not working class.” And I just threw it aside and I wrote that book and then I kept thinking, “Well, what are secretaries?” They earn working class wages, but they think of themselves often as middle class. So that conundrum really drew me in.

AA: That’s really interesting. So let’s jump into the book, and I have some questions for you if that’s okay. Maybe I’ll just ask you questions and then you can take it away. I wonder if we can start, again, like I referred to in the introduction, if you can tell us about el angel del hogar. Where did this ideology come from? Did it come from Britain, did it cross the ocean and people were reading Coventry Patmore in Latin America, or how did that happen?

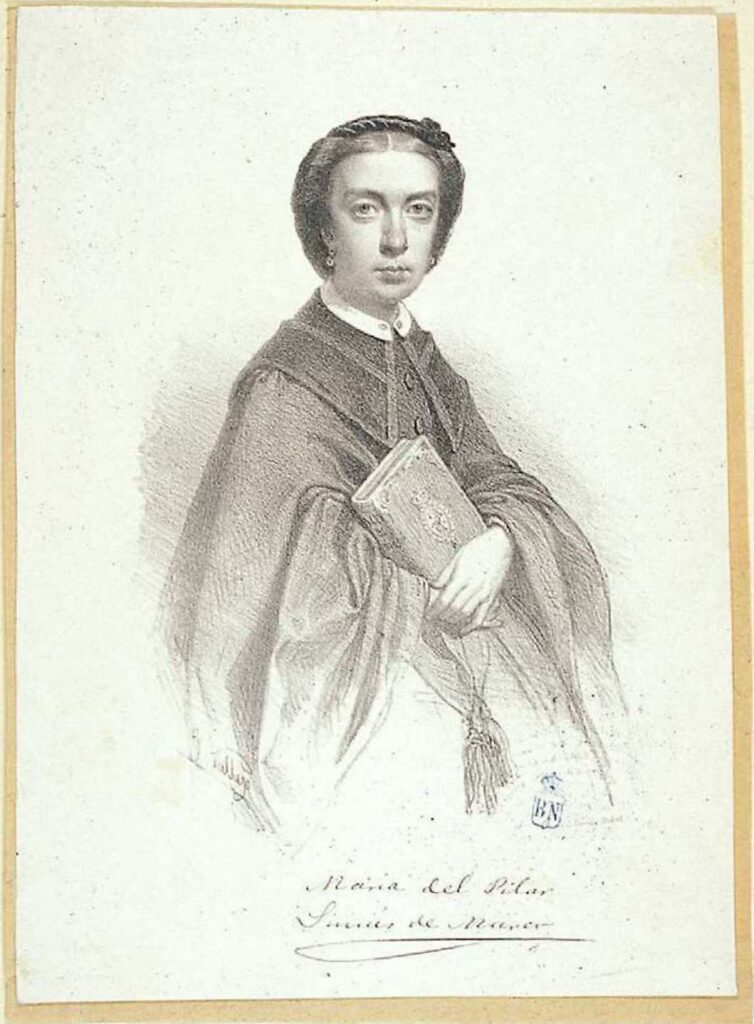

SP: Yeah, so there was a woman in Spain named María del Pilar Sinués de Marco and she wrote a book in 1859 called El angel del hogar. And Sinués de Marco was interested in celebrating what women did in the home, so she was in some ways promoting women and what they did, giving value to the emotional and domestic labor that women perform. But it came out of this particular moment when those ideas in Spain were circulated throughout Latin America, including in Mexico. So in Mexico in the 19th century, there were women’s periodicals named Angel del hogar, it was a phrase that appeared in the newspapers. And it’s not so much that the idea was imposed from Spain, but rather that it’s a part of a shared not only intellectual culture, but a shared conception about middle class respectability and women’s role in that. It circulated in Mexico, but it also echoed economic circumstances in Mexico.

AA: Interesting. I’m also remembering that in your book that you refer to, I think it was a book that was also called La perfecta casada that was a lot earlier, right?

SP: Yeah, La perfecta casada was published in 1583 and it was written by Fray Luis de León. You know, I don’t think of literature as making things true, but a reflection of society. So he was expressing the value that many people put on women’s seclusion from the public, just as you said in your introduction. That respectable women stay home, their families can afford to keep them at home raising children, either performing domestic work or overseeing people who do that work for them. But see, he really had idealized the physical seclusion of women and then it’s taken up decades later in a similar way. And I think what’s important there is that the historical context may have changed, but that association of women with the private sphere and the way that it contributed to de-legitimizing women who entered into the public persisted, just in different forms.

AA: Well, that was my next question for you, was how women’s presence in the home was, you write that it’s “a key to middle class identity.” So you talk a lot about which women could do which jobs and that that determined their class identity. Can you talk about that a little bit?

respectable women stay home, their families can afford to keep them at home raising children…

SP: The book starts in the 1890s, and prior to that period there was quite a bit of polarization between the social classes. So a white, educated, well-off upper class on the one hand, and then in many ways subjugated peoples with little access to education, who perhaps were artisans, perhaps worked in the countryside, often people of color, so mestizo or indigenous peoples. And so you had this very polarized class system because of the polarization of the economy. There’s the haves and the haves-not, it was a very dichotomous class structure. Over time, and as the economy developed, a middle kind of emerges, right? But people are still concerned about their appearances, how people perceive their ethnic identity, whether or not they can keep their women at home. So all of those things become markers of distinction. And the middle class is very concerned with not being associated with the working class.

AA: Once middle class women did start to work a little bit, what jobs were acceptable? Were there any jobs that were acceptable for these upper class or these middle class women to do that could still retain their status?

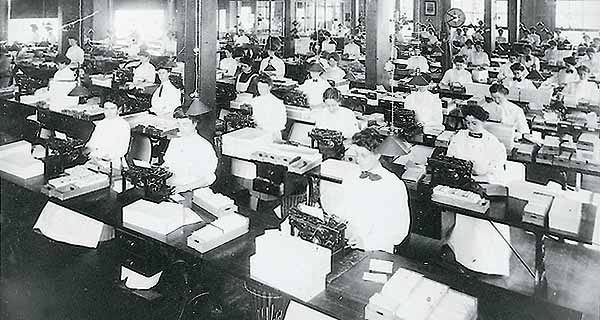

SP: There had been a decline in this ideal of seclusion in the mid-19th century in Mexico City in particular, and the historian Silvia Arrom looks at that. There had been an economic recession and high levels of male mortality, which meant that people in the home needed women to go out and look for work, right? There have been studies done for the United States that are really interesting that haven’t been done for Mexico, but with the production of consumer goods, the value of women’s labor in the home declined. So the more you can buy a broom or clothing or butter, the more families are looking for cash to be able to buy those things and what women are doing at home becomes less valuable. Historically, that’s a process that occurred. And it’s probable that that same process affected Mexico and that then you have women who need to look for work outside of the home. They weren’t going to be working as street vendors because they don’t want to be on the streets associated with Native American women in Mexico City, so they began to look for things and it sort of coincides with the expansion of office work. So the Mexican government supported the expansion of women’s education. Those women get an education, they start to work in offices as secretaries and typists and all sorts of different kinds of office work. They also were teachers, this is roughly the time when there’s an expansion of the role of women in primary education in particular.

AA: This was a really interesting part of the book for me, too. You talk about vocational education that was started I think, by the government, right? And that was offered to men and women, but there were different offerings dependent on gender, right? Could you talk about that?

SP: Yeah. So in the mid-19th century, there’s an expansion of education in many different countries. For example in France, there was a national school for administration bureaucracy that opened in 1848. And in Mexico this occurs just a few years later. Those schools in the mid-19th century were available to men, not to women. And this is something that we’ve seen with all sorts of professions where 1) access to education and 2) access to professional organizations allow for the perpetuation of male privilege. So the history of doctors versus nurses. Doctors go to medical school, nurses go to nursing school. There are different associations. That keeps a hierarchy and a control of knowledge and access to jobs from which men benefit. The same thing happened in Mexico in the mid-19th century with commercial education.

In Mexico, there was a vocational school that opened in 1856 for men. There wasn’t one for women until 15 years later. There was a commercial school that opened in the late 1860s and didn’t allow women to enter the classroom until 1894, which actually is quite early, but was many years after men were allowed to attend those classes. And women were so eager for this education and the work opportunities that it would open for them that in 1900, and this is one of the cool things I found in the archive, this group of women wrote a petition to the wife of the president and they said “This school is really important to us. The classrooms are overflowing with women. And we heard you’re going to hire another teacher and we would really like to ask that it be a woman, because we would like a woman to teach us in this space.” And I see that really as this moment of demand of women wanting that education and organizing and making a petition. And I don’t have a response from the wife of the president, but they hire a woman shortly thereafter. So that demand, I think, was seen as important. If it wasn’t heard, it was seen as important, certainly.

AA: So you talk about a term that you call “the feminization of bureaucracy”. Can you talk about that also?

SP: Sure. In the late 19th century, the Mexican economy expanded significantly. And the number of reports that need to be written, and letters that need to be sent, and meetings that need to be organized increased. And there are new offices that open or they become increasingly important. There’s an expansion in the importance of sending mail, so the post office expanded significantly in the late 19th century. And the way that bureaucracy expanded was such that it integrated women into a public administration and the bureaucracy in a way that put them in a subordinated position to men. So it’s not that they expanded a bunch of high paying government jobs. But rather said, “Okay, well we’re going to hire women to type or write letters and sort mail” or what have you. So that means then that a woman would learn how to take dictation from a man that she reported to. She learned how to type the words of a man who spoke out those words that she then typed out.

There were other ways that women were integrated into the workforce that subordinated them to men. For example, the titles, right? So many men, not all men in the bureaucracy had a college degree, but those who did were called licenciado. It’s a word that indicates that level of education. Women, educated or uneducated, 16 years old or 65 years old, were all referred to as señorita. Throughout the ‘20s, 1930s, even now sometimes, that’s their title. It’s not their job title, but that’s how they’re referred to, is señorita. So what that meant then is that there’s this structural inequality between men and women that is based on the way women were integrated into the workforce.

And we often talk about the way inequalities in the home and in the family lead to inequalities in society. And I think that’s true, but I think it’s also important to point out the ways that the shape of the workforce reifies, reiterates, makes concrete inequalities between men and women. A contemporary example would be that if you work somewhere where there’s not maternity leave, or you’re a woman and you’re a secretary and your salary is X and you’re married to somebody who’s a lawyer and his salary is Y, when it comes to deciding who’s going to step out of the workforce to take care of kids, well, as a household to some degree it makes sense that the woman steps out of the workforce because she’s making less money. So that inequality in the workforce reinforces inequalities between men and women at home.

Women, educated or uneducated, 16 years old or 65 years old, were all referred to as señorita. Throughout the ‘20s, 1930s, even now sometimes…

AA: I’ve never thought of that! In all of the books that I’ve read on the podcast, honestly, that mutually reinforcing kind of vicious cycle, I’ve never thought of that before. Like you said, I’ve only thought of it the other way around, that a little girl raised in a family where she sees like her dad presiding over her mom or whatever, she sees that and then it forms the expectation that she’ll have for herself professionally. But I never thought of the professional dynamics impacting the home. That is so interesting.

SP: And I think it’s because in the United States, many of us, especially people who think of themselves as middle class and professionals, we have no labor consciousness. We don’t think of ourselves as workers. That’s another thing that I tried to do with this book is to show that you might call yourself middle class but you’re still a worker. I’m a worker, I’m a professor. I spend all day at work and I am subject to the rules of my workplace, my salary, and what I can and can’t do. All of those things are shaped by workplace rules. But we don’t think of ourselves as workers, and therefore, I think we sort of dismiss those gender inequalities in the workplace. I think it’s important to think about.

AA: Yeah, that’s really interesting. And on a similar topic I was going to ask you about salary inequalities too. And one phrase that really jumped out to me and grabbed my attention from the book is that one landowner described women as “cheaper than machines”. I think this was in the context of farm workers, so this wasn’t in a secretarial context, but I think across the board women were paid a lot less than men. I guess that’s obvious. But can you talk about that a little bit? Perhaps these different fields of work and the dynamics there?

SP: Yes. The quote that you mentioned is from the work of Francie Chassen-Lopez, who’s a wonderful historian who was looking at rural Mexico and the decisions of employers as to whether or not to buy certain machinery for their commercial agricultural production or to hire women. And they decided that women were cheaper, so you might as well hire the women to do it. In the case of the women I study here in this book, these women work for the federal government. I’m not looking at all secretaries, I had to limit the study. And in the federal government, every job is paid the same wage, so you don’t have a man and a woman hired for the same job being paid differently. And the reason I bring that up is because it’s important. I am sure that you’ve probably talked about this on your podcast or thought about it, but it’s important to think about the many factors that contribute to the gender wage gap. And so what happens is 1) women are integrated into these lower paying jobs and 2) because they didn’t go to the same schools as men, they don’t have the same professional networks so it’s harder to get promoted. Then sexism in terms of promotion. And that’s in particular in the earlier years. And I want to say when I’m critiquing the Mexican workforce, these are things that happen in the United States as well. So I’m not pointing at Mexico without keeping in mind that these things also happen in the United States. It’s not about Mexican machismo or something like that. Patriarchy’s everywhere. So there were different things that contributed to women earning less. There’s social factors that I didn’t really look into in this book in terms of women stepping out of the workforce when they have children. My next book is looking at discrimination against women in the workforce for getting married or for pregnancy. So those factor into the wage gap. I’m not sure if I answered the question completely.

AA: No, that’s great. And one complicating factor that you bring up in the book too was that the class definitions are more complicated than I had thought of. Because you point out that the class definitions are different for women than men. Like some jobs were a move downward for men but a move upward for women. So for a woman who’s upwardly mobile, she’s really excited to get a job as a secretary. But if you see a man take a job as a secretary, you think, “oh, poor guy.” So that was a really interesting thing that you pointed out too.

SP: In the late 19th, early 20th century, women were on the rise. They’re getting more education, they’re getting access to new jobs. But those jobs are, to use a Marxist term, it’s “the proletarianization of administration”. So there’s been a breakdown in the production of paper and documents and communication, and the women are eager for those jobs. And some men are falling into those jobs because they have fewer opportunities. And that proletarianization and the tension that it has created historically between men and women is something that we’ve seen in industrialization and different moments of different fields.

AA: One topic that you write about in chapter one is just the word “feminism” and what feminism meant in Mexico in the late 19th century. Can you talk about that?

SP: Yeah, there’s a historian named Karen Offen, who’s a fabulous historian who identifies some of the early uses of the word “feminism”. And I’m particularly interested more in how historical actors have used the word “feminism” than academics, like myself, defining a group of women as feminists. Offen identifies Hubertine Auclert, who lived from 1848 to about 1914, as the first self-proclaimed feminist in France. And Offen argues that the word féminisme, feminism in French, began to circulate in France in the 1890s and it was synonymous with women’s emancipation. Offen claims that this word jumped from France over the Atlantic to the United States and Latin America. Now, jump is not particularly specific. And as a Latin Americanist, I’m always curious, well, how did those things actually happen? And what did it mean for the people, for example, in Latin America who began to use that word in the 1890s?

The word “feminism” in Latin America, since those early years of it being used, has really been kind of fraught. Because it’s been a word that women themselves have used, but that many people who want to shut down that conversation will say is a foreign export. Feminism is something that women in the United States care about. In the late 19th, early 20th century, many people would say those frigid, selfish women in the United States who don’t want to be mothers are the ones that are talking about feminism, but our women, using the possessive, in Mexico or what have you, aren’t really interested in feminism. But they were. They were.

And some of the earliest uses of the word “feminism” in Mexico referred to this shift in women’s workforce participation. It was a way of describing this change. But the women’s movement, some women call themselves feminists, others didn’t. It’s a super rich and complicated history. I’ve talked a little bit about some of women’s workplace demands along with those sort of concrete demands – equal pay for equal work, an end to the glass ceiling, respect for women’s seniority at work – there was this effervescent, super rich conversation that went on in the 1920s and ‘30s in Mexico about the changes in women’s relationship to family and to work. So, for example, there’s a woman named Leonor Llach who worked in the Mexican bureaucracy all her life. She wrote stories and newspaper articles about all sorts of things including feminism and women’s work. And I have a quote here that I thought I would share with you.

many people would say those frigid, selfish women in the United States who don’t want to be mothers are the ones that are talking about feminism, but our women…aren’t really interested…

She wrote, “Marriage has become a necessity, even a commandment or sentence without appeal. Woman, from the time she’s a child, is spoken to of love. And when young, of marriage. If she cannot make the two coincide, too bad for her. And no young lady from a good family of 20 years of age could admit that in life there is any other option for women than marriage.”

So what is she doing there? She’s talking about the way that women are educated to think of themselves as a product. As something that men choose. And that she needs to think of marriage as what she’s going to do. That’s all she’s going to do, even if she doesn’t love the person. There’s also reference in that quote “no young lady from a good family at 20 years of age could admit that in life there’s any other option for women than marriage,” so good family respectability is based on a woman getting married. She can’t think about working outside of the home. And Llach is challenging that. She calls mothers hypocrites and questions– She was also a huge defender of mothers. Let’s not talk about mothers as this sort of abstract ideal, let’s support them with childcare, let’s support them with a living wage. So there’s a lot of redefinition of motherhood that went on at this time that I just think is so important. As a working mother myself, I’m so appreciative that those restrictions were loosened up.

AA: Well, if it’s okay to jump ahead to chapter seven, that was, I thought, such an important thing too. Because you talk about daycare in the 1940s. Can you talk about that a little bit?

SP: There’s this boom of women in the 1920s who enter into the workforce of the Mexican bureaucracy. They’re secretaries and typists and what have you. And they start to have some complaints about their work, but they are not permitted to join the same organizations that men are forming. So really they start to then meet with other women and one of the things I argue in this book is that that’s one of the important origins of the women’s movement in Mexico. These working women secretaries who came together, went to conferences, started talking about their circumstances, began writing these things like the quote that I read about Leonor Llach. But it’s not until that kind of boom of women in the generation in the 1920s who gains experience within the workplace that they are able to make certain demands, like the demand for childcare. And some of the earliest demands for childcare then come from these women who worked in the Mexican administration, in bureaucracy. And they were among some of the strongest actors within the unionization movement in the 1930s, and they started to demand daycare.

AA: And they start to get it, right?

SP: And they start to get it, yeah. Little by little. And Mexico’s interesting because in 1917– So in 1910 there’s a revolution. And by 1917, there’s a new constitution and Article 123 is a very progressive pro-labor article in the constitution. And women are promised maternity leave, they have a constitutional guarantee to maternity leave.

AA: Wow.

SP: But the move from law, from paper to practice is a whole other story. And daycare continues to be an important issue of debate in Mexico. The current presidential administration cut a lot of federal funding to daycare and it’s got some people mad.

AA: I was in Mexico City last year and was talking to some people there and said, “So what do you think of the president?” And they said, “Mixed reviews! Because he’s great for some people, but he’s not known as being particularly great for women.” So, I know that’s in the national discussion still, as it is here, and it’s still so needed. And that’s really remarkable that it was written into the constitution of their nation. So at least if it’s not being implemented maybe as well as they think, at least it’s documented and one of their aspirations, which is more than we can say here, unfortunately. One last topic that I wanted to ask you about is the representation of motherhood in film.

SP: I take up the representation of motherhood in film in the last chapter of the book. And it’s a really fun story because there’s a woman named Sarah Batiza who worked as a secretary for the federal government. And at some point she leaves that work and in 1950 she wrote a book called We the Shorthand Typists in Spanish, but that’s how it translates. And it’s this amazing book about the daily life of this group of women who work in an office as secretaries and what they do, and what they think, and what they think about men. And one of the important stories in the book is the way that the unequal relationship between men and women in the workforce is perpetuated outside of work. So there’s a young woman, María Eugenia, in the novel who begins to date a licenciado. So she’s señorita, he’s licenciado. They begin to have a relationship, and then she finds out that he’s got a respectable fiancée from Guadalajara. And Guadalajara kind of represents a very Catholic society, so it represents something in Mexican culture, that reference. And she’s devastated and then comes to find out that she’s pregnant, and without really saying that she does this, she learns that she has the option of having an abortion. And he offers to pay for an abortion and she says, “I love this child because it’s mine, not because it’s yours.”

So the novel’s very interesting and right after it comes out, they make a movie about it and the movie is completely different. That women are cat-fighting with each other, and there’s all this chisme and gossip and tension. And the story about Maria Eugenia in the movie, one of the secretaries, becomes pregnant because of a relationship with a man that she works with, a licenciado. And at some point she confronts him and tries to have a conversation, and then she walks out the door and gets smacked by a bus and dies. So it’s just like there’s not going to be any single motherhood in this 1950s film. And women who work and who succumb to men’s come-ons are going to pay for it. And I think that’s important because it tells us that people make choices when they write books and they make choices when they make films. And then those are the stories that fill our heads. And of course, you know, some viewers are critical and everything like that, but that becomes a part of the narrative. Like still in 1950, there’s this image that women should not work outside of the home because if they do, they’re going to be working with men who are going to seduce them, and then they’re going to get pregnant and be single mothers and get hit by a bus.

there’s this image that women should not work outside of the home because if they do, they’re going to be working with men who are going to seduce them…

AA: Hahaha. Let this be a lesson to you.

SP: Nobody wants that.

AA: No, nobody wants that. Yeah, that’s true! And again, it reflects the culture but then it reinforces the culture. Like you said, it becomes yet another story in our heads. And there are so many fingerprints on that, right? There’s the person who writes the screenplay and then there’s the person who produces it. It’s not one person’s pet project that only a few people see, it reflects a bunch of people who are saying, “Yep, I’ll put my stamp on that. That’s what I want to put out into the world.” Which really is a shame.

Well, this brings us to the end of our discussion today. Is there anything else that you’d like to add as a final takeaway?

SP: It’s important to recognize that while this is a history about Mexico, and Mexico City in particular, there are books that have been written about the United States and the expansion of bureaucracy and the integration of women into office work. There’s a really great book called Sex and the Office that’s a history of women in office work. And these same phenomena have occurred and continue to occur in the United States. So this is not about something particular about Mexican culture, but rather about, I would argue, the historical evolution of the workforce and the way that women have been integrated into that workforce, the way that inequality between men and women has been reinforced by the organization of the workforce. So it’s more about that than about cultural specificity. And of course, there are particularities to Mexican culture: the writing and the way that women organize, the words of those women who stood up for their rights is particular and should be celebrated. But these are phenomena that are cross-cultural.

AA: Well, Dr. Susie Porter, thank you so much for your time today. I learned so much from your book and from this conversation. Again, Dr. Porter’s book is From Angel to Office Worker: Middle Class Identity and Female Consciousness in Mexico 1890-1950. And again, thank you so much for being here today! It’s been such a pleasure to get to know you and to learn from you. Thank you so much.

SP: Thank you, what a great podcast. It’s really been a pleasure to talk.

It’s not about Mexican machismo or something like that

Patriarchy’s everywhere.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!