“You really can’t have men do this”

Amy is joined by Dr. Dee Mosbacher and Dr. Boden Sandstrom to discuss their documentary, Radical Harmonies, exploring the history of the women’s music movement, Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, and how countless lesbian lives were transformed through lyrics and song.

Our Guests

Dr. Dee Mosbacher & Dr. Boden Sandstrom

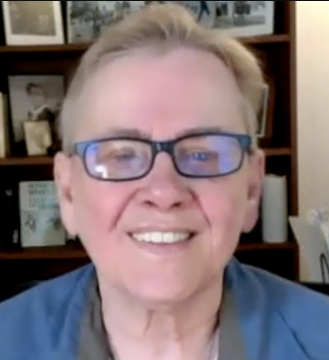

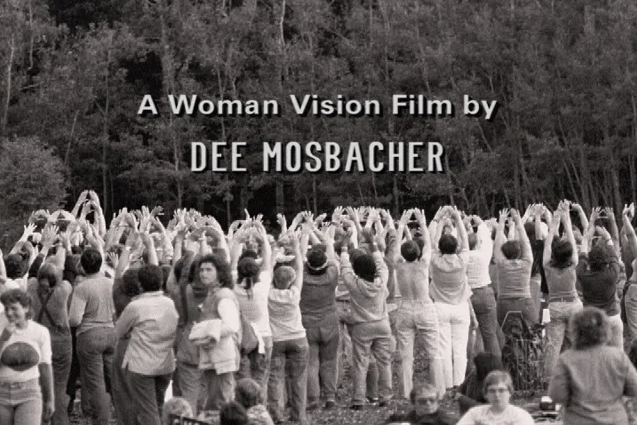

Dee Mosbacher, M.D. Ph.D., is a psychiatrist and an Academy Award nominated documentary filmmaker. Dr. Mosbacher has been an activist for women’s health since the early 1970’s. She has directed and/or produced a total of nine documentaries on homophobia, including Out for a Change, Addressing Homophobia in Women’s Sports, All God’s Children, De Colores, and No Secret Anymore: The Times of Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. Dee and her spouts, who is also a psychiatrist, Dr. Nanette Gartrell, worked to eliminated homophobia in the DSM. Dr. Mosbacher is the founder and president of Woman Vision, a nonprofit organizations whose mission is to promote social justice through the production of educational films and video.

+++

Boden Sandstrom, Ph.D., was the winner of the American Musicology Society Philip Brett Award. She was a leading sound engineer on the women’s music circuit, and in 1975 she founded Woman Sound with singer Casse Culver. She toured with many performers, including Chris Williamson and Lily Tomlin, and did sound for the major women’s music festivals and concerts at the time. She has a Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology, an M.S. in Audio Technology, and an M.L.S. in Library Science. Before retiring, Dr. Sandstrom was a lecturer and technical coordinator in the School of Music at the University of Maryland.

The Discussion

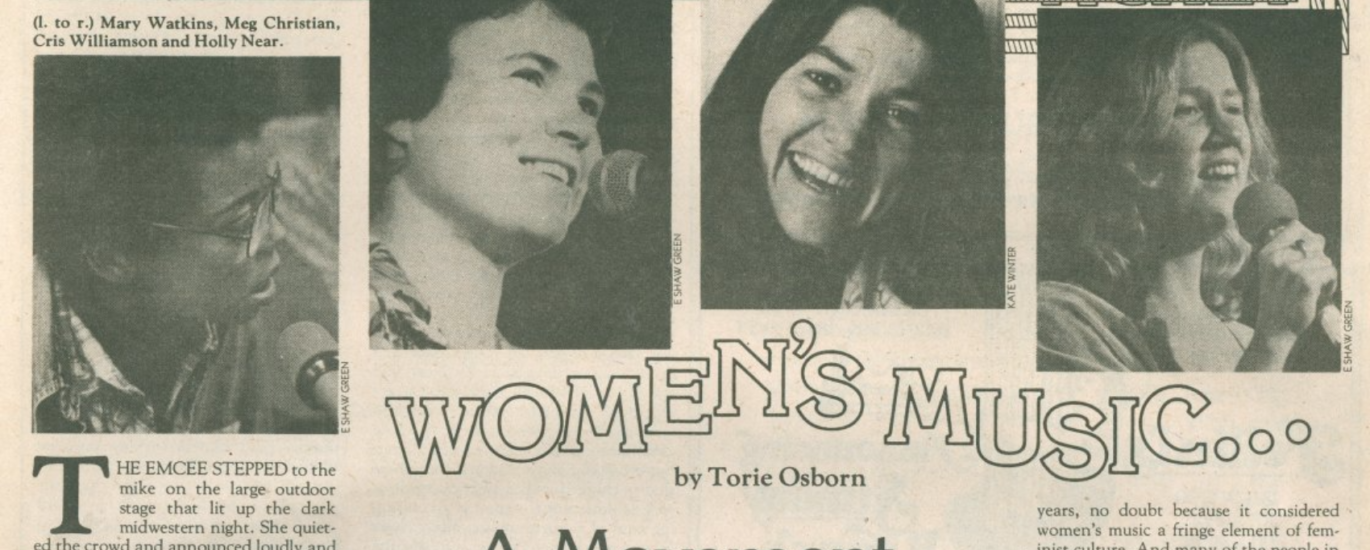

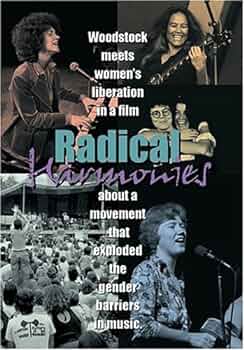

AA: I recently watched a documentary film from 2002 called Radical Harmonies. This film was described as “Woodstock meets women’s liberation in a film about a movement that exploded the gender barriers in music.” I learned so much from this film, and I want to open with a quote from drummer Ubaka Hill. She said, “every single human being came through the womb of a woman and therefore every single human being had their first experience with rhythm through the heartbeat of a woman.” Today we’re going to talk about women in music, and specifically the events of the 1970s and 80s that changed the landscape for women musicians forever.

And to speak about this topic, I am so happy to be joined by my friend, Dr. Dee Mosbacher, who was the producer and director of Radical Harmonies, and Dr. Boden Sandstrom, who was the co-producer. Welcome, Dee and Boden. I’m so excited to have you here today.

DM: Thank you very much, Amy.

AA: So as usual, I’m going to read your professional biographies first, and then I’ll have you introduce yourselves a little bit more personally after that. And I’ll start with you, Dee.

Dee Mosbacher, M.D., Ph.D., is a psychiatrist and an Academy Award nominated documentary filmmaker. Dee has been an activist for women’s health since the early 1970s. During medical school and psychiatric residency, she began a second career as a documentary filmmaker, co-producing Closets are Health Hazards: Gay and Lesbian Physicians Come Out, and Lesbian Physicians on Practice, Patience, and Power. In response to the 1992 election—in which the Republican Party used homophobia as a fundraising tool—while her own father was H. W. Bush’s secretary of commerce and then chief fundraiser, she co-produced and directed the film Straight From the Heart, which received an Academy Award nomination.

Dee directed and or produced a total of nine documentaries on homophobia, including Out for a Change: Addressing Homophobia in Women’s Sports, All God’s Children, De Colores, and No Secret Anymore: The Times of Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. These films have received a total of 46 awards from LGBTQ Black, Latina, Latin American, and Aging Media film festivals, including Best of Show Awards, Grand Jury Awards, and Audience Awards in the U.S., U.K., Australia, Cuba, Mexico, and Italy. These films have touched people’s lives across the world, changed people’s minds about homophobia. and improved the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals. Dee and her spouse, who is also a psychiatrist, Nanette Gartrell, worked to eliminate homophobia in the DSM.

Dr. Mosbacher is the founder and president of Women Vision, a non-profit organization whose mission is to promote social justice through the production of educational films and video. And I’ll just throw in here that Dee is a fan favorite and is returning to Breaking Down Patriarchy Dee and her wife, Nanette, appeared in our Season Two of Breaking Down Patriarchy, and I’m so excited to have you back, Dee.

Boden Sandstrom, PhD, was the winner of the American Musicological Society Philip Brett Award. She was a leading sound engineer on the women’s music circuit, and in 1975 she founded Woman Sound with singer Casse Culver. She toured with many performers, including Chris Williamson and Lily Tomlin, and did sound for the major women’s music festivals and concerts at the time.

Other clients included the Smithsonian Institution, Roadwork, Joan Jett, the National Organization for Women, The D.C. Committee to Promote Washington and RFK Stadium. She was a technical producer for the Cultural Festival of Gay Games 4 and the Stonewall 25th Anniversary in New York City, and the major national now and LGBTQ+ rallies, the D.C. Gay Pride Day and Taste of D. C.

She has a Ph. D. in Ethnomusicology, an M.S. in Audio Technology, and an M.L.S. in Library Science. Before retiring, Dr. Sandstrom was a lecturer and technical coordinator in the School of Music at the University of Maryland.

Okay, both of you just have the broadest and deepest work experience I think I’ve ever heard of—such an amazing array of activities that you’ve participated in and contributed to. So I’m really eager to hear you kind of expand on both of those personal stories, so either one of you can start and just kind of acquaint us a little bit more with what that felt like personally as you went through.

DM: Well, I want to start by saying Boden and I have been friends for 50 years, maybe even a little bit longer. We worked together in various political organizations against the Vietnam War, against racism and for abortion before it was pro-choice and for women’s rights. I came out during that period and Boden was a huge support for me during that time, being just slightly older.

I hope you don’t mind Boden. We’ve been friends all these years—bi-coastal friends, by the way, since I’m on the West Coast and she’s on the East Coast—but we find ourselves sort of back in a situation where we’re fighting for the same rights on many levels that we were back then. And that’s part of the reason I thought it was so important to bring this film, Radical Harmonies, to a younger generation, to both educate and inspire during this period.

We were invited to show the film at the Martin Luther King Library in Washington, D.C. and the audience was on the younger side, which was great and quite diverse. And they were blown away by the film. They had no idea that this whole movement had happened back in the 1970s to the 1990s, and it really inspired us to bring this to a whole new set of people.

AA: Well, I am so excited to bring it to a whole new set of people too, because I had the same experience. I had no idea about any of this history when I watched the film. I just watched it a couple of weeks ago. No idea about the history and also the film itself is so well done so I really highly recommend it to viewers and listeners, and we are going to feature some clips of the film as we go.

But Boden, I’d love you to add anything… I mean, I read kind of like the awards and the accolades and the major bullet points, but if you could maybe zoom in a little bit and tell us where you’re from, even, and what brought you to do that work.

BS: I would have loved to do that. For me, women’s music and this whole experience of creating Radical Harmonies and where that’s taken me to really transformed my life. My passion drove me into women’s music was that I played the French horn for years and years, since elementary school. And then as I developed my professional life, my first job was as a librarian, which I loved.

I loved reading and I loved being a librarian, but when I made my way to Washington DC, and in fact, I was a librarian at the Martin Luther King library, which is where we showed the film so that was the full circle for me…but I was very bored. I was in my twenties, and I was quite bored being a librarian. And to back up a little bit, I came down to DC from Boston where I had discovered feminism and I joined Boston Female Liberation and really started to get liberated and understand the oppression of women much better for myself and how we could free ourselves with collective action and political action. And so when I moved to DC, I sought out other feminists and started working for the Washington Abortion Rights Action Center. And some of the women I met, this was in 1972, already knew about the women’s music a little bit.

There was just some budding women’s musicians in the D.C. area, and I went to my first, what became known as women’s music, was a Meg Christian concert at the Women’s Center in D.C., and that just blew my mind because she was saying what women’s music came to be known as and described as “women identified music”, that is women writing music, singing about women, and singing for women. And the song that I remember from that concert was called ‘Ode to a Gym Teacher’, which was hers and most of our experiences of kind of having a big crush on our gym teacher as the first big strong woman that ever came along, is the line from her song.

And, you know, it was a jam-packed audience in this small room in the women’s center. Almost all lesbians. And it just transformed all of us because we had never heard music that spoke to us that way, and we didn’t see each other before as a group. So that was a huge component of women’s music that was so important. And then from there… we’ll get more into it, but I did start a sound company with my then later on spouse, Casse Culver, and called Woman Sound. And then I learned how to become a sound engineer, and when I retired from being a sound engineer, I decided I wanted to teach and I needed to get a Ph.D. in order to teach at a college level. And I chose ethnomusicology because I had mixed in so many different ethnic communities and different multicultural communities in D.C. area. And that worked out great for me. I loved doing it, and that’s where I started to do the research on women’s music because I wrote my dissertation on Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival.

And then once I retired from there, I put all my energies into archiving women’s music herstory. And that’s what I’ve been doing since I retired. So hooking back up with Dee to start showing Radical Harmonies again is just such a joy and delight and we’re having so much fun. And, and as she said, seeing the reaction of people who have never seen it before is just wonderful.

AA: Well, something that comes to my mind, too, just listening to you, this is so important for all of us to learn from you, and I think especially for young LGBTQ folks who probably can’t even imagine what it was like to not be able to just connect to other people on the internet. Like to just find people online. It’s so much easier now. Thank goodness, right? We have technology that can connect and you can find people in other communities where that didn’t exist until fairly recently. And, and so to study queer history and understand the shoulders that everyone is standing on is really, really important.

So, I’m really grateful for your perspective that you bring, and just as a reminder of what things were like, again, not very long ago. So, thanks for bringing that up.

DM: And I just wanted to say, you know, coincidentally, I was listening to Fresh Air the other day, and I was listening to an interview with this new young songwriter and she said, “Well, when I was in high school, I was making this music. I was writing these songs and none of the boys would accompany me.” And so she said, “I think it was a gender thing.” And then she described the music industry as the quote, ‘Wild West’. And I don’t know about you Boden and Amy, but I have certain stereotypes that I associate with that kind of description of it because she later talked about men trying to tell her how to do her music.

So just a reminder that not only do we want to let people know what it was like back then and how we responded to it, but that it still goes on. And particularly, I think even more so in this period.

AA: That’s interesting. Thank you for bringing that up, that it’s an ongoing problem, that sexism in the music industry, unfortunately, hasn’t gone away. And one of the things that I value so much in studying history is that it gives me ideas of like, other people have done this before in certain ways. And sometimes we waste time and energy reinventing the wheel when people have encountered really similar things. And we can go, Oh my gosh, it worked for them. I bet I could tweak a little bit and it could still work today.

So it’s still relevant, unfortunately still needed, but yes, I’m so I’m very excited to dig into this story. So I’ll start by asking you how you hatched the idea for Radical Harmonies? What were some of the things that were going on in your lives, or how did the idea come to you? And then talk about the process of filming, and then what the reception was like for the film. Do you want to start, Boden?

BS: Oh, okay. Well, for me, when I decided I wanted to become a sound engineer, it was just incredibly mind blowing how difficult it was that the whole industry was all male, period. And how I got inspired to become a sound engineer was I saw a woman named Judy Dlugacz who was part of the Olivia Records Collective. They were still in DC, but they were moving to LA to become a record collective, and she still runs Olivia right now. But I saw her mixing on stage at a small concert at GW University. In fact, I think Dee was with me, and it was another one of my first women’s music concerts. I was so excited about what she was doing because it involved music and I could see there was a technical component, and I was really good at math and science.

I was, like I said, fairly unhappy in the library, so I went up to her afterward and asked her, how do I get to do that? And she told me that Casse Culver was a singer, songwriter, and she had a small sound system and she was looking for someone to train because she was tired of singing and mixing all at the same time. So it took me a year to track her down—in fact, I ran into her at a lesbian New Year’s Eve party—but she did agree to train me and her then partner, Mary Spotswood Pugh, who had a production company called Athena Productions, was doing an every Thursday night lesbian music concert at a club in Southeast Washington called Club Madame. And that’s when some of the women who were singing in other cities first started to come to D.C. so that we could hear other performers besides the ones in D.C. and they would come regularly every Thursday night and I would mix and do the sound and people that came there from the D.C. world really liked the sound and the mixing and started asking us to do sound at other events, political events, and rallies and that kind of thing.

So Casse and I decided that what was needed was to start a woman’s sound company. Then that’s when I decided I really needed more training. And I called up every male sound company in the city, just about, and asked if I could come and volunteer to get training or to work. And it was just a flat no across the board. They didn’t even want me to show up to volunteer. They really didn’t want to turn the power over to women at all. And I finally found one company, these two great guys—it was actually a big rock and roll touring company and they fabricated all their own speakers is called National Sound and they became really good friends of me and Casse.

They were willing, but not without hazing… and this was typical of women all over the country if you tried to get into the industry. I had to come down and load a semitruck in the middle of the night with these huge speakers ‘til four or five o’clock in the morning—and that was my hazing. And since I kind of passed that, they said, “Well, okay, you can come down to the shop and we’ll talk to you.”

it just transformed all of us because we had never heard music that spoke to us that way, and we didn’t see each other before as a group

AA: Oh my gosh. That is blowing my mind.

BS: Yeah, it was outrageous. Isn’t that?

AA: You could get sued for that now. I mean, thank goodness you can’t do that anymore. That is crazy to me.

BS: Yeah. It was always fraught with problems. I mean, whenever you were in an all-male environment you did have to worry about your safety as well. So I was always guarding myself, really. But these two guys were willing to share their knowledge. And yeah, we rented our first equipment from them because we started doing bigger jobs than what we had equipment for. And we’d go down and they would teach us how to put it together and talk to us about how it worked and then we’d go to…you know, I remember the first time I ever did it I think it was another Meg Christian concert at All Souls Church this time, which was a place where so many wonderful women’s music concerts and political rallies work for years. It still has those kinds of concerts there. It’s just a classic D.C. political enclave. Anyway, I remember, I got the whole thing set up and it didn’t work. We didn’t have cell phones, so I had to run down the hall, up the stairs, and get on the pay phone with Tommy. We called him Mr. Wires, and he would say, “Well try this, try that, try this.” And then I’d run back and I’d try it and it wouldn’t work and I’d have to run back out.

And finally I got it to work and it was a really good concert. So eventually one of the nice products was I became a really good troubleshooter, you know, figuring out how to make these things work. And eventually we bought our own equipment, but I was working on my dissertation now as an ethnomusicologist on the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. And I was just appalled at the lack of research that there was on women’s music. Which, now it had been 20 years, so there should have been a lot of articles. As I was researching every other subject, I would just find a ton of information. And so that was when I was talking to Dee, I was telling her about that. And, and then she said, amazingly enough, she said, “Let’s make a film.”

So that’s how hard it was for women to get into the business.

AA: Wow. Dee, how about you? How did you kind of come upon this story, specifically, that you wanted to tell through film?

DM: Well, when Boden was working on her dissertation in the late 90s, Boden, what you said to me was, “Gosh, I can’t find any information. There just is no documentation.” And she came to me and said, you know, let’s consider documenting this really vibrant part of our herstory and I said, yeah let’s do it. And I have to say sometimes ignorance is bliss because if I had known how many music rights, performance rights, photographic permissions, etc… I’m not sure this ship would have left the harbor. But thank goodness there were so many women who were passionate about this film, that they were really helpful and cooperative whenever possible. So that really made it work. And, you know, there are a lot of things that I love about the film.

Of course, I love the music, but one of my favorite things is that it demonstrates just how important women’s music and the whole industry that grew up around them was for women, particularly more rural women who were might have been a bit more isolated and you know, remember in the early seventies, we had no internet; we had snail mail. And many of us are lesbians; categorically we were thought to be criminals, sinners or sick. And a lot of us felt like we were the only ones. So, when primitive women’s music production companies showed up—with, you know, maybe one or two performers, a microphone, if they were lucky, sometimes megaphones—lesbian lives were transformed.

AA: Amazing. Well, thank you for sharing that. So let’s dive into the content of the film and kind of bring these stories to light. Again, I recommend to people that you watch the whole film because it’s so good, but we’ll give you just little teasers. And maybe first, what we’ll do is have you both set the scene for us by telling us a little bit about the landscape at the time.

What was it like? We’ve talked a little bit about this already, but maybe some more stories to illustrate what the industry was like for women in the 1960s, maybe for composers, performers, producers, technicians? What was it like for women? Expand that a little bit more.

DM: Well, Boden talked about her situation as a sound designer and a sound person. The situation for women, and particularly for lesbian women, had always been abominable in terms of the music industry. And the examples in our film are almost too numerous to count. But we have included a short clip that exemplifies what two women, trying to enter what was referred to as the ‘cock rock’ culture, encountered.

AA: Perfect, let’s play that clip.

DM: So, needless to say, there were very few outlets for women who wanted to record an album because as I said, the whole industry was controlled by men. So we had to build an alternative industry that was controlled by us.

AA: That was such a great clip. And I want to use the film a little bit more to kind of illustrate some of these points. And one thing that I got from the movie throughout as I was watching it is that… I mean, I’ve been learning about what things were like for women in general in the midcentury, mid-twenties, mid-thirties, fifties, sixties, seventies, but this film just highlighted for me so much that if things were bad for straight women, then they were much worse for lesbians, right?

And so maybe we can play the clip that shows Angry Athis and Maxine Feldman? Can we play that clip?

DM: Needless to say, there were very few outlets for women who wanted to record an album, because the whole industry was controlled by men. So we had to build an alternative industry that was controlled by us.

AA: Yeah, you would have to… I mean, I guess not you would have to, but there was an opportunity to do that, I guess, that you would want to be separate.

So how would you define that? Maybe I’ll ask. This to you first, Boden, and then Dee, you can answer afterwards. How would you define the women’s music cultural movement? Maybe you can talk about the who, why, when, where, and how, like how did that women’s music cultural movement develop?

BS: Well, the women’s music cultural movement developed over time, way back starting in the late 60s, and early 70s in particular. Once women’s music musicians started performing and getting out there, not just sitting at home writing—which Casse, my partner and spouse did. And when she was very young, sat and wrote her songs and sung them to herself and cried herself to sleep, as she said in one of her songs—and once they started getting out there and the lesbians and women who wanted to hear them more, just started figuring out how to make that happen.

Athena Productions in D.C. is a really good example of just, okay, here’s a club. Let’s organize ourselves, call ourselves a production company, make some flyers, get some word out and get people to come. And then the crowds, the women come and then they started touring around the country somewhat and that had to be publicized. And this was happening during the women’s rights movement, which was called the second wave of feminism. And there were a couple of components to that that contributed to this. One was the cultural feminism, which was many of us looking at the artistic part of our heritage that was lost or never was allowed to be out, like different women artists.

We uncovered different women artists, composers. We looked at our spirituality, goddess and earth-based spiritual practices that were buried. And so it was like a renaissance of us looking at our culture. So there was that component, which obviously music fit right into.

And then there were many of us who were wanting more than economic equality, let’s say, that really wanted to be completely full human beings, and kind of were described as radical feminists; pushed harder, wanted to alter the cultural life rather than just the political life. And then a wing of that too was lesbian separatism, which is really important because when we talk about women’s music festivals, Michigan in particular, the spaces were for women only—outdoor spaces, women only, and it was a separate space. And it developed… I mean, this was really spontaneous and following our needs and what we really needed to do to become full human beings, but it turned out that it was the major factor that allowed this circuit to be created. We tried to tell that story in Radical Harmonies because we cover 20 years.

So you can see the whole evolution of how this evolved, but Washington D.C. was a really good example of this because, for example, when we held concerts we now have—this is just after 2 years, we started Woman’s Sound in 1975—I got there in 1972, and I heard my first women’s music concert, so you can see it happened really quickly. But by then we had a woman lighting company, Aerial Lights. We had a company that serviced our cars, Grease Palace. We had Lama’s Bookstore, which sold the tickets. We had Tina Lunsen, the printer, who printed them, and Serena Marcus, the graphics designer, who made the flyers.

We had our own feminist credit union, and this just didn’t come out of a vacuum. This came out of this whole lesbian separatist philosophy, which one of the centers was in Washington, D.C. It was the collective called The Furies who put out their own newsletter with furies and they became the Olivia Collective that then went to L.A. and started the first women’s record company, Olivia Records. And so, it was just this convergence of all the stuff happening within the second wave of feminism.

DM: Absolutely. I would define women’s music as that whole alternative industry and culture that was built mostly by lesbians. It was built because, as photographer Joan Byron said in the film, there was nothing in the culture that could nourish us, that helped us to flourish. Or, as Alix Dobkin, a singer activist said, women’s music was created by lesbians because we had to have it. We needed it. Cause, yeah, I just wanted to say that, you know, obviously this wasn’t the only thing that was going on with female performers and musicians during this period, but it was the only music that was created, staged, produced, and disseminated by women. Mostly lesbians between the 1970s and 1990s.

AA: So it really was just a separate kind of parallel universe, right? Of music that was designed by and for women.

BS: Yes. It was parallel, but the other unique component of it was, obviously, it was underground. It was an underground network, which is pretty amazing. I mean, we didn’t rely on mainstream media or press to further it at all, and nor did they know about us, which is why Radical Harmonies is so important, because people still don’t know what is going on, how to change the women’s role in the industry. And it didn’t happen by magic because some of the women that came after us, like Ani DiFranco, who’s in the show, she acknowledges that she was inspired by our independent record companies, because prior to that, women were recording for male record companies and they literally could not say and sing what they wanted to.

A really good example is Melissa Etheridge. Because I met her at the West Coast Women’s Music Festival when she was 16, and she was singing in clubs. And she did get a record contract and she got that record contract. She sang all of her best songs that we all love and the way they recorded them, she absolutely walked away from her first record contract because she was so disappointed with how they sounded.

And it’s the same with Casse. When she was picked up by Farris Wheel Records, she was dumped because she came out as a lesbian. This is a company up in Woodstock. And if you listen to the recordings that they made, they wouldn’t release her whole album that they recorded. I listened to them and she sounds so different. They have so much vibrato on her and she’s buried among all the instruments. And I mean, it’s nice, but it’s not who she really was. Without the inspiration of the work that we did, you know, it probably wouldn’t have happened the way it did.

AA: And just to clarify, so she was dropped not for singing about a girlfriend or singing about the lesbian experience, but just by coming out, just simply being known as being a lesbian was enough to get them to drop her?

BS: Well, her music, the ones they were recording, it was generic pronouns. So, she wasn’t singing to a ‘she’, but they were lesbian love songs—not necessarily, not all of them, but most of them, but they were going to hook her up with Janice Joplin’s Full Tilt Boogie Band after Janice passed and she came out in the middle of it as a lesbian and they would not release her music or put her on the road. It devastated her.

That’s when she got to Washington, D.C., she came back home. She grew up in Bethesda and they sat just like Motown artists. Once you’re contracted, they sit on all your songs. They, own your songs. She couldn’t get back her best songs until in the nineties when she bought them back for her after 30 years.

AA: And that’s still happening. My reference point is Taylor Swift, re-releasing all of her songs so that she has control over them and has ownership of them. So that’s, again, still continuing, right?

she came out [as a lesbian] and they would not release her music or put her on the road. It devastated her.

BS: Yeah. Unless you know differently and you know how to do it and you start your own record company and insist on complete control, that’s what happens.

Yeah. And a few of them I mean like Indigo Girls and Ani DiFranco. I’m sure there’s quite a few other examples of women that have started independently.

AA: So one more question I have about the industry because it’s hitting me now even more than when I watched the film is that the industry, the music industry itself, if you’re starting this whole other underground industry, you’re going to need to like build that up by, like you said Boden, with people who are sound engineers, which typically you’re not going to find a lot of women who are trained in that.

So how did you build that industry and train women for jobs that they hadn’t necessarily gone to college for, maybe, or how did you build the business aspect and the technical aspect of that during that time?

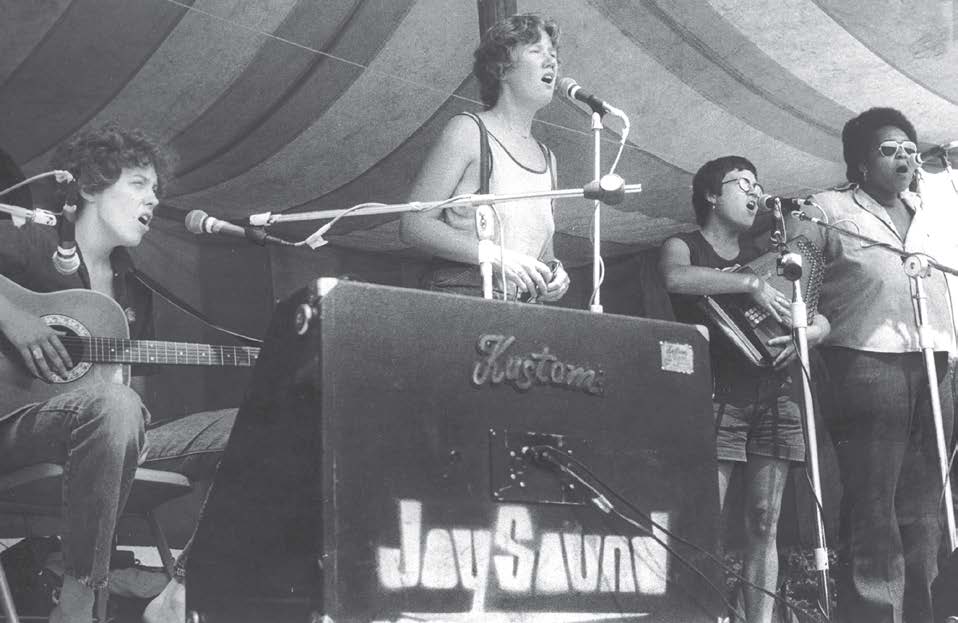

BS: The biggest developer of that was the Women’s Music Festivals, the National Women’s Music Festivals. That’s where we all came together and Michigan is a really good example. I mean, they started out really small, and they had to rent the tents and the port-a-potties and the sound systems from the male companies in the Michigan area, but they did bring in a few of the people they knew had some of the skills, like the sound engineers and lighting people.

And then other women came and worked at the festivals and volunteered and they learned how to do these in the areas that they wanted to. And as we grew, then more and more women could be brought in with the skills like the cooks and the lighting people, the electricians. But just like I was as a sound engineer, I had very limited skills, but once I got to the festival, I could mix on a big stage with a big sound system and act after act and be with other women engineers that we could share information. It just catapulted me into a whole other arena of skills. So we got to do work that we could never do in the non-separatist world. In fact, in the film, Linda Tillery says that she got to produce albums, which was the thing she was really good at. She got asked because she was a woman. Not in spite of it.

DM: I think Boden has covered it really well and I think it is demonstrated in the film. I mean, if we have some wonderful shots of women building Michigan, basically, because it had to be torn down every year for many reasons and rebuilt every year. And so there’s all these really strong women out there, you know, putting the stages together and just building the whole thing from scratch every year, which is really incredible. Outdoor showers, electricity…

BS: Absolutely. And at the peak, Michigan was 8,000 women and they were feeding 8,000 women with these big cauldrons over open pit fires and they had a big fire ceremony where they started the fires before everyone got there and they kept those fires going through the entire thing. All the women, everybody’s skills were so amazing. Lisa Vogel, the producer had these iron cauldrons designed just for this purpose, this fit nicely over the pits and you didn’t see them in the film, but it’s amazing.

AA: So cool. So to pivot to a new topic, several women in the film talked about the women’s music industry, this new developing women’s world of music being mostly white and middle class. Can you speak to that a little bit?

BS: Yeah, well one of the women who spoke about that in the film is Penny Rosenwasser, and really what she was talking about was the beginnings of the women’s music industry, and particularly, our references are mostly around the big festivals because that’s where we got together, and that’s where we talked about such things. And what we were talking about was that our culture reflected the dominant culture, since we were a part of it in the sense that white women had more privilege than Black women, Women of Color by and large, just as in society. And so what you were seeing was as these different women’s businesses developed and the women’s music festivals develop is that white women had the means, even though many of us didn’t have much means—it’s not like we were wealthy—but we were going to college and maybe we could not work a full time job for a while to do this, something that we were passionate about or whatever and maybe we didn’t have children.

So we were the ones who were putting this all together, but we very quickly started to be challenged about this by Women of Color and the perception started to change. It was clear that Women of Color were writing and performing women’s music alongside of us all along, it’s just not necessarily in positions of prominence. And so the great thing about the festivals and the record companies and producers is starting to really challenge all of us, each other on our inherent racism and to make space and to start looking around and including people within whatever we were doing.

The festivals are really a great place for this, and some more than others. And we have a really great clip to show you that we could introduce now with Judith Casselberry talking about her perception as a Black woman. When she performed, she started with Casselberry-Dupreé and it was one of my early experiences when they came to All Souls Church to perform. That’s when I first met her and she’s still a friend of mine. And then Ivy Young is talking, she’s a producer and she’s talking about that topic as well. And she was a producer for Sisterfire, which was a multicultural festival that was produced annually in Washington, D.C. by Roadwork. And Roadwork’s emphasis was being multicultural and multiracial.

And then Bernice Johnson Reagon talks, she was a civil rights performer, but then she started Sweet Honey in the Rock. And she talks about her experience with Redwood Records—which was run by Holly Near—of reaching out to her, wanting to record a non-white group. And this was happening fairly early, and so, I mean, it’s sort of misinformation in a sense, especially if you see Radical Harmony today, and that line sticks out. You kind of think that all 20 years it was like that, but that’s not exactly what happened.

And then we struggled a lot at the festivals. We had workshops and really talked about a lot of these issues. And one of the solutions at Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, for example, was to create a Women of Color tent, which was often the solution around identity issues, just as our space was. It was important for lesbians to have separate spaces to grow. It was also important for Women of Color. We had a Jewish tent at Michigan, you know, so everyone could develop themselves.

AA: Oh, that’s so cool. Let’s play that clip here. And I’ll just throw in too that Bernice Johnson Reagon is a lesbian. It’s special to me because she was in SNCC. She was in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, so I knew all about her. They did tons of fundraisers during the Civil Rights Movement and their music has been recorded. So when she popped up in the film, I was so excited, like, “Oh, we know her!” And that was fun.

So yeah, let’s watch that clip.

AA: So, to continue on this topic of women’s music festivals specifically, as they’re separate from recording a record, for example, why were music festivals so important for women?

DM: Well, it’s interesting that one of the people we interviewed said, you know, that a lot of people think that the midas of women’s music was either the East Coast or the West Coast or both. But really, it was happening in the middle of the country, and one of those places was in Champaign Urbana, Illinois, when Kristen Lems went to some men who were putting on a festival and asked why there were no women invited to perform at the festival. And they said, well, there are no women who are good enough. So you’ll hear her response to that in the following clip.

AA: Yeah, I love that clip. I mean, I hate it, but I think it’s so important. It’s hard to hear, but so awesome. Like the engine that kind of propelled everything forward sometimes…it’s anger, right?

DM: Exactly. Anger can be an inspiration.

BS: Yeah. And the other thing that happened at this festival was that Amy Horowitz, the producer of Roadwork, who produced Sisterfire, and I drove from Washington, D.C. to the National Women’s Music Festival, the first one in 1974, and I wanted to mix. And I hadn’t been invited because Kristen didn’t know about other women’s sound engineers and she was actually going to have her boyfriend mix. I think Margo, who’s now one of my best friends, came from the west coast, but that’s the only engineer she’d ever heard of. And so I got there and I found her and I said, “Kristen, I really wanna do this. You really can’t have men do this, and I can do this.”

And I of course had no idea if I could do it or not whatsoever, because it was huge, you know? And she let me, so I got to meet Margo from the west coast and we shared mixing and shared skills. And like I said, she’s still my best friend, so tribute to Kristen.

AA: That’s such a great story though. I love that. I mean, the whole story is so great, but that detail that you shared of like, ‘Hey, I can do that. Give me a chance.’ And privately you’re like, I’m not sure that I can, but I’m going to try and it just illustrates so much that sometimes society will have a limitation and then we even have our own mental limitations of doubt. But if we can just remove the barriers, we can grow into things and—just thinking historically—things that people thought women couldn’t do because women weren’t allowed to try to do. You know what I mean?

And so proving that wrong to everybody around you and proving it to yourself, like, technically I’ve never done it but I’m going to try. And then what do you know? Women can do stuff that we didn’t think we could do. So that’s such a great kind of illustration of that whole concept.

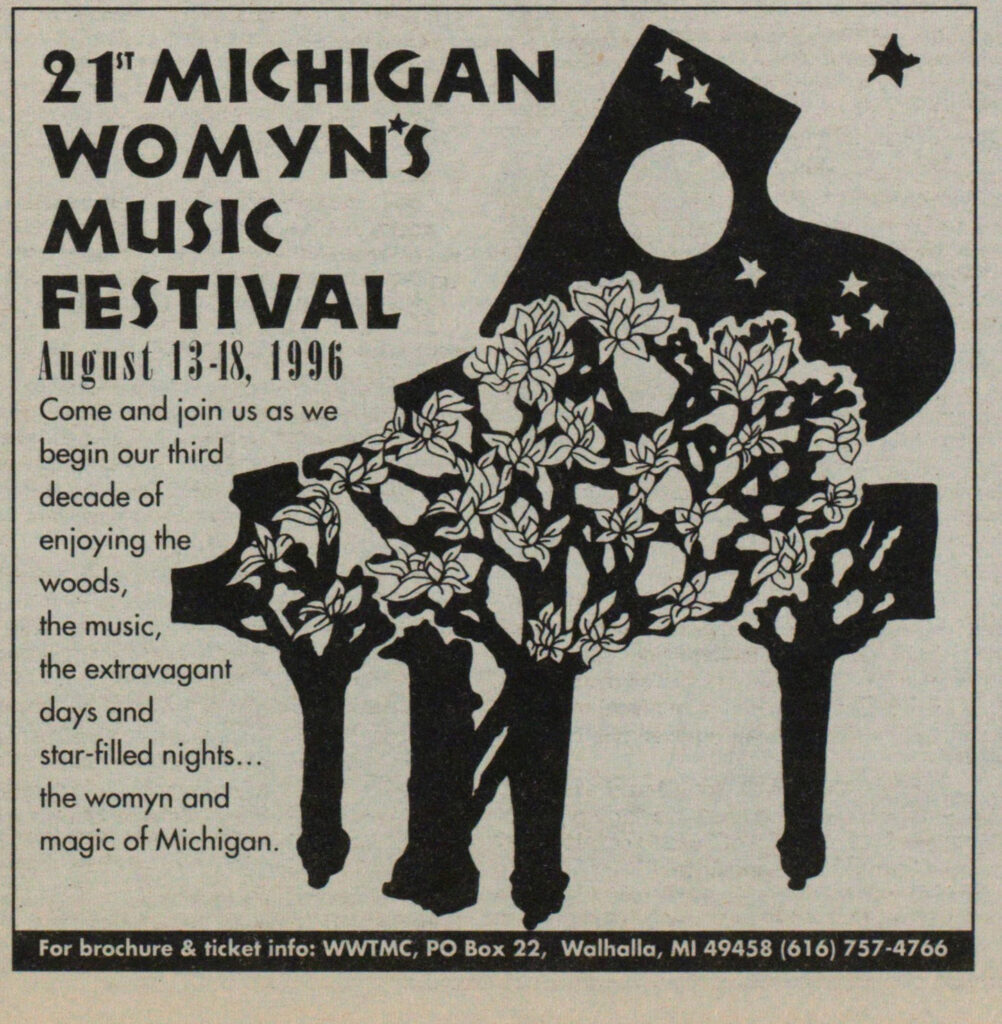

And then Boden, let’s dig in a little bit more to specifically the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. Can you talk about that one specifically?

BS: Yes, Michigan started in 1976 and it really became the heart and center of the Women’s Music Network. In that, once again, like Dee said, being in the Midwest, it was central so people could get to it, but the fact it was very different from the National Women’s Music Festival in the sense that that one was in an auditorium at a university. But Michigan was the first one that was built outdoors, and it was built by three women, a little collective, and these women were fairly middle class, let’s say. And they just had this idea of hosting something outdoors to hear women’s music. And they, as Lisa says in the film, Lisa Vogel, who became the organizer, she said that they would just have what she called ‘a little kegger in my town, Mount Pleasant, Michigan’ and get their friends to come and they pass the hat. They stop the music, like, Meg Christian’s great song and stop it in the middle and pass the hat so that they could keep hearing it. And they mimeograph little flyers as Lisa says in the film with a purple ink and pass it around at national that they were having this thing.

And people couldn’t quite grasp the fact they were going to hold this thing outside and how were they going to do that. How are they going to feed people and where were people going to sleep and all that? But they did it and it was one stage, very, very, very, very, very primitive. You know, like the tents hardly staying up and the sound system hardly working and all that. But 2,000 women came, and they only expected like 500 or so. So it was just a scramble, but it all worked and everybody had a great time and then it just kept going.

And it stopped, I think at the 30th year, was it? But anyway, at its peak it grew into three stages. It just kept growing and building. And as we’ve talked about earlier, everyone got to hone their skills and learn how to do things. But the other thing that it was really good for was that not only did we get to hear this incredible music, but we got to do our work and so any issues that were problematic in any place in the country would be brought there and we’d have workshops and we would hash it out—how to deal with it, what to do with gender issues, race issues, ethnicity issues, religious issues. And the performance was a big component of that because the women’s music performers were singing about the issues. And as we know, music is so powerful.

The reason that it worked and we solved so many problems was because of the music, not that we were just talking at workshops. So it was this unique place to be and, back to how important it was to have the separate space, we had to be separate to get away from being so discriminated against in the patriarchal culture. And that leads me to how important another component of this festival is, which is how safe it was.

We made it very safe. We had patrol safety people around at the perimeters and it was women only and so women came there feeling for the first time that they could walk through a woods without looking over their back. And which was just unheard of and they could tent without worrying about who was going to come to your tent. So it was just an incredible space. And what I wrote my dissertation on was the significance of the opening and closing ceremonies. Because those of us that were practicing, Earth-based religions or goddess-centered religions were really starting to create the safe space spiritually.

And so these opening and closing ceremonies just spontaneously grew over the years and they really became something that everyone looked forward to and felt the spiritual component of that; that we would open the space and we would close the space and so that we could do our work. And so I wanted to lead into another clip of women that are just discussing this safety issue, and it starts with a Kay Gardner, who was a spiritual practitioner, she became a high priestess, playing her flute and she played on the main stage since the very beginning, even when we weren’t even thinking about opening and closing ceremonies, but she created the first opening ceremony. And then it’s Ubaka Hill, who you’ve already met and she’s talking about how this is sacred land. And then it goes into Diane Gomez, who’s the head of security talking about how important the safe space is. And then Judith Casselberry again, talking about what Dee mentioned; why she could bring her mom, since it was a safe space.

AA: Okay, Dee, do you want to jump in after the clip?

DM: Yeah. I mean, not only, and maybe because a safe space was created, many of the advances that we see in society today were created to accommodate all the women who wanted to be part of the festivals.

And we have a clip about some of those accomplishments at the festival.

DM: These are the some of the things that had an impact on women that have ripple effects, as I said, that we still feel today. And Amy, if it’s okay with you, the last clip I would like to share goes back to what I was talking about in the beginning about the existential impact of women’s music on lesbian lives. And particularly, this is a clip about two women, Brenda and Wanda, who went to Robin Tyler’s first ever Southern Women’s Music Festival.

And this is not in the clip, but you know, this was in the South. This was the first time they were taking lesbian music to the south and there were a lot of concerns that the Klan, because it was a Klan area, that they might show up and so it was everybody was a bit on edge but this particular clip is about two women whose lives were transformed.

AA: I think that’s a wonderful place to wrap up our conversation. This has just been such a delight to hear kind of the behind the scenes and the backstory to this film. And I’d love it if you could tell listeners and viewers where they can find the whole documentary film. Where can we find that?

DM: Thank you. This documentary and all of the films created by Woman Vision is available online at womanvision.org to watch or download for free. If you’d like to schedule an event at your college, university, library, or church, please contact me, [email protected], and just be sure to put Radical Harmonies in the subject line.

AA: Perfect. Again, Dee and Boden, thank you so much for being here today. Is there any last something that you’d like to share before I just close out?

DM: Well, Amy, I know you’ve interviewed my spouse of coming up on 50 years, Nanette Gartrell and I before, and I really appreciate you having me back to talk about this and we’re deeply grateful.

AA: Yes, it’s been such a joy and an honor to have you back, Dee. Give Nanette a huge hug from me.

not only did we get to hear this incredible music, but we got to do our work

DM: Will do.

AA: And Boden, thank you too.

BS: Yeah, I’m just so happy to be here too. I really, and I’m going to look at more of your segments to see because it’s just such a great thing that you’re doing and I’m going to share it with a lot of my friends because we’re so many of us are still politically active and need inspiration.

DM: Absolutely, Amy, they are really inspiring. I’m so glad you’ve added the YouTube. That’s really fantastic.

BS: Yeah. The other thing I wanted to say is if you do want to have more conversations about Sweet Honey in the Rock anytime, because I really did do their sound for about 10 years, exclusively in D.C. and I can tell you that their sounds still live in me. It was like going to church every day with Bernice. She just imparted so much to every audience. I was just always mesmerized by what she said, such an inspiration.

So yeah, it was so important. It was just the fabric of my sound life in D.C. was speaking with them. And of course, instrumental to introducing me to so many other people and to do work.

AA: How cool. Well, thank you so much. Thanks again.

Women’s music was created by lesbians because we had to have it.

We needed it.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!