“reproductive issues are more broad than just abortion and birth control”

Amy is joined by Dr. Brianna Theobald to discuss her book Reproduction on the Reservation as well as gender roles in Crow culture and the history of reproductive rights in Indigenous communities.

Our Guest

Dr. Brianna Theobald

Dr. Brianna Theobald is an assistant professor of history and affiliate faculty in the Susan B. Anthony Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies at the University of Rochester. She is an award-winning teacher and researcher in the fields of U.S. women’s and gender history, the history of Native America, and the history of reproduction. Her first book, Reproduction on the Reservation: Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Colonialism in the Long Twentieth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2019), explores the intersection of colonial and reproductive politics in Native America from the late nineteenth century to the present. This book has received multiple awards, including the Erminie Wheeler-Voegelin Book Award from the American Society for Ethnohistory. Theobald’s research on Native women’s history has appeared in academic publications including the Journal of Women’s History and The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, and she has also published in venues including Time Magazine and the Washington Post. She is currently working on two book-length projects, Making the Impossible Reality: Genealogies of Indigenous Women’s Activism and Safe Haven: Feminisms and the Domestic Violence Movement.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Today I want to start by reflecting on the experience of having a baby. Any listeners who have had a baby, think about your own experience. And any listeners who haven’t had a baby, perhaps you can think about someone close to you, like a spouse or a sibling, or maybe stories from your own mother about your own birth. For me, I can remember wanting to have a baby, and then I remember using a pregnancy test from a grocery store to find out I was pregnant, and then thinking of a fun way to tell my husband. And then doing fun activities to tell my own family of origin, my parents and my siblings, and my husband’s family. And then when we had older kids, telling them they were going to have a new sibling. Especially with my first baby, there was a big celebration among the women of my community. I grew up in Denver, Colorado, and I wasn’t living in Denver at the time, so I flew back to Denver so that my mom and all of her friends who had watched me grow up could throw me a big baby shower and give me gifts. And then there were all the books I read about childbirth and my birth plan, and lots of prayers from family members for the baby’s safety and my safety. And then when my babies were born, they received a blessing at church from all the men in our family and community who loved them and welcomed them into the world. So from start to finish, having a baby is a deeply personal experience and it’s deeply tied to family and spirituality.

And I wanted to start the episode this way because today we’ll be discussing the book Reproduction on the Reservation: Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Colonialism in the Long Twentieth Century by Brianna Theobald. The book does such a beautiful job of reminding the reader that reproduction is so much more than just a biological function. On the cover of the book is a painting of two young Native American women who are pregnant. And I spent a long time looking at that painting before I even opened the book to get me into that headspace of remembering that these are real people’s lives, real people’s loves and families. And I’m thrilled to introduce our guest today, who will be talking about Reproduction on the Reservation, the author of the book, Brianna Theobald. Welcome, Brianna!

Brianna Theobald: Thank you so much for having me.

AA: I’m so excited to dive into this book today and talk about all of the amazing things that I learned from it. But first, we’ll start with your professional bio, and then I’ll give you a chance to introduce yourself a little bit more personally. Dr. Brianna Theobald is an Assistant Professor of History and affiliate faculty in the Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies at the University of Rochester. She’s an award-winning teacher and researcher in the fields of U.S. women’s and gender history, the history of Native America, and the history of reproduction. Her first book, Reproduction on the Reservation: Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Colonialism in the Long Twentieth Century, was published in 2019, and it explores the intersection of colonial and reproductive politics in Native America from the late 19th century to the present. This book has received multiple awards and, as I said, is the text that we’ll be discussing today.

Theobald’s research on Native women’s history has appeared in academic publications, including the Journal of Women’s History and the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. She has also been published in venues including Time Magazine and The Washington Post. She is currently working on two book-length projects, Making the Impossible Reality: Genealogies of Indigenous Women’s Activism, and Safe Haven: Feminisms and the Domestic Violence Movement. All amazing projects, Brianna. And again, I really loved this book and learned so much. I’d love it if you could introduce yourself a little bit more personally. Tell us where you’re from and what brought you to do the work that you do.

BT: Sure. So the question of where I’m from is weirdly a little bit complicated. I was born in Minnesota, so there might be some times in the course of this podcast when you’ll really catch the Minnesota. But we moved away when I was quite young, two or so, and moved quite a bit growing up, mostly in the Great Plains heartland. My dad was an academic so we were following him from college town to college town and then we landed in rural Nebraska when I was in junior high. And then I went on to do my undergraduate work and to get a master’s degree in history at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. University of Nebraska, Lincoln has a really strong field in the American West and in Native American and Indigenous history.

And so I entered that master’s program with an interest in studying U.S. women’s history and I had the privilege of working with an amazing advisor, Margaret Jacobs, who, when I was working with her, published this really important book. It won the Bancroft Prize, and it was about the removal of Indigenous children from their homes in the United States and in Australia. It was kind of a comparative work. And I thought that, first of all, that was such an important history that so few people knew about. And also, I thought it was so amazing that someone’s job was to learn and then write and teach these types of histories, and that struck me as really important. I also think working with Margaret, who was looking at the removal of children and following these children to boarding schools in a later book, she looks at their removal into the foster and adoptive systems, so looking at those particular trajectories.

I think that’s what really led me to think about the mothers and the families from which these children were removed. And of course I came to learn that the families from which they were removed meant something different in many of their conceptualizations. It was much broader and less nuclear than the kind of family upbringing that I had. So I think that’s really where I became interested in and excited about this body of work. And then I went on to do graduate work in Tempe, Arizona. And ironically, although the book centers on the Crow Reservation, which is in Montana, it’s actually through some connections in Arizona that led me to the Crow Reservation, which has become such an important location for me for all sorts of reasons over the past seven or eight years.

AA: Can you start us off with a brief summary of the book before we dive into the details?

BT: Yeah, I wonder if I could circle back to where you started with the cover, which I just adore. It is a painting of two Crow women, and it’s actually based on a historical photograph from 1911. These were real, living, breathing Crow women sisters, one of whom was pregnant. It’s this really striking image of one supporting the other in pregnancy. And the reason I like to give a real shout-out to this cover, it’s striking, it’s so beautiful, and it was painted by a Crow artist named Ben Pease. So I always like to give a shout out to Ben Pease Visions. He’s immensely talented, and it was really special that he was willing to let me use this painting, which he painted in 2018. It’s called Of a Path Known by the Old Ones. And part of why it was so special is because not only am I a fan of his work, but I interviewed many of his aunties and grandmothers for the project. So that felt appropriate and special to return to the idea that the real people whose histories are involved in various ways.

So that brings us to Crow, which is important for the summary of the book, because this started as a dissertation for me, which is quite common with academic books. And it was initially policy history, so I used a lot of government records to piece together that policy story. But what I came to realize as I was doing that, in the course of researching and writing that, is that it just didn’t make sense to me. It didn’t quite work to talk about and think about the policy as separate from the women and the communities who were experiencing them. So I did a pretty significant transformation from the dissertation to the final book.

And part of how I did that was I decided that I really needed to dig down at the local level. Crow is not necessarily representative. There’s such variety, but I need to be able to better understand, first of all, the circumstances in which these policies were being imposed. And then what was going on with the ground and what families and communities and women were doing. And so that’s what led me to this idea of having an extended case study of the Crow Reservation. Again, I landed on the Crow Reservation for a few different reasons. It had appeared in a lot of my archival research, so that was part of it. But in a moment of real serendipity, I happened to encounter a Crow writer named Valerie Jackson who was living in Tempe, just blocks from me as I was working on this project. And she happened to be the granddaughter of Susie Yellowtail, who is a key figure in the book. So she was really my introduction to Crow and to her family and to extended kin, especially female kin. What ended up happening is that the structure of the book really follows the Crow story as richly and as grounded as I could. And that is then interwoven with this broader story of policy and also broader federal and national trends.

AA: That really came through as I read it, and I so appreciated that you would talk about policy and national trends and what the government was doing. But then it was always grounded in real people’s lived experiences with names and relationships, and I could very much relate to it as a mother, as a member of a community, and as a human being. It really told a very compelling human story. I highly recommend that listeners get this book. In fact, I didn’t mention this to Brianna, that I found your book because my oldest daughter goes to Boston University and she’s taking a class on the American West, and your book was part of their curriculum. So my daughter recommended it to me.

BT: Oh, that’s wonderful. I so appreciate hearing that.

AA: Yeah, it’s a fantastic book. Let’s talk a little bit more about the Crow, and maybe what we can do is structure the conversation chronologically. So we can talk about pre-European contact and specifically about gender relationships in Crow society before colonizers arrived. What were some of the features of gender relationships among the Crow?

BT: I will say that the book stretches from about the late 19th century pretty much to the present. I got as recent as I could. And so I kind of jumped in at what really was a moment of significant change in contact, but it was also at a moment when there had been various forms of contact between Crow people and various Euro-Americans: traders, certainly soldiers, increasingly settlers, as well as missionaries, so lots of different folks. One of the things that I look at is this moment in the late 19th century, and that’s kind of my starting point. So I can talk a little bit about what I see then, and that’s not to suggest that this was unchanging for millennia before. Of course, culture is always dynamic and always changing and evolving.

So it’s kind of like what I can see at this moment, more so than pre-contact it’s pre-medicalization, which accompanied colonization, especially going into the 20th century. And I should emphasize also that anytime we’re talking about Native America, we’re talking about more than 570 distinct nations speaking hundreds of languages. So there’s tremendous diversity. But at Crow, as is the case in a lot of other indigenous societies, scholars typically talk about gender relationships as being complementary rather than hierarchical. Which is to say that when you’re looking at social roles and division of labor in daily life, there was often a kind of sex segregation of labor. Men and women occupied different roles. But what we don’t see so much is the hierarchy of roles, of man’s role being more important. We don’t see as much of that. But in some ways, in broad strokes, it can kind of resemble a division of labor that might be familiar to, say, Euro-American colonizers at the time, right?

Crow men tended to be involved more in what we might think of as governance and hunting and warfare, though there was certainly more involvement of Crow women in governance and certainly political deliberation than we would see among their Euro-American counterparts. But women tended to have more responsibilities for home and childcare, lots pertaining to the domestic realm. Also gathering, some agriculture. So different responsibilities, both pretty much equally valued and certainly deemed equally necessary.

And when I’m talking to my students about this, because those divisions can seem somewhat familiar, but where you start to see the distinction between their Euro-American contemporaries is when you look at the control of resources and power in those realms. The classic example with Crow is that the women owned the home and all domestic equipment within it. And that had all sorts of implications, right? If a couple decided to separate, or if a woman decided she wanted to leave a marriage, the home was hers. This is also a matrilineal society which is, again, common but not universal among indigenous societies. Crow was and is a matrilineal society which means that a child inherited the clan identity of his or her mother. So that’s also really important for the centrality of women in these domestic spaces. Some folks talking about other indigenous societies have used the word “matricentric” so it’s very women-centered in ways that I think differ from their Euro-American contemporaries.

anytime we’re talking about Native America, we’re talking about more than 570 distinct nations speaking hundreds of languages

So that’s a little bit about gender, and maybe I could transition to bringing in family, which is of course very much related. I alluded to this earlier, that when colonizers came in, the idea was that the nuclear family unit was the pinnacle of civilization. It was super important in terms of forcing people to understand the value of private property. So missionaries and eventually the government would attempt to impose this nuclear family structure of a husband, wife, and biological children. That is not how Crow kinship was experienced and recognized in the late 19th century. It really isn’t in many cases to this day. They have extended family units. One’s clan is far more important. I think it’s really important to realize that in Apsáalooke, the Crow language, there isn’t a word for one’s aunt. A Crow child would use the same word to refer to their mother’s sister as to their biological mother. And so if they wanted to refer to their biological mother, they would have to qualify or specify that term. And I think that’s really key for understanding through language how family was even understood and recognized. This had all sorts of implications in terms of who was involved in daily childcare. Again, women were certainly important. Maternal uncles were also very important. Grandmothers often had a role in daily childcare. But it was also super common for children to spend some time living with a maternal aunt, so with one of their other mothers and to move a lot. There was a woman in my book that I quote, her name was Agnes Yellowtail Deernose. And she talked about how Crows liked sharing children. We don’t think of it as giving them up, right? Of losing them. We’re sharing them so everyone is gaining. And I think that’s an important thing to keep in mind too, in terms of what family life actually looked like on the ground.

AA: Yeah. And that leads me to the next question that I wanted you to talk about, which is specifically about reproductive practices. Because there’s this sense of women teaching and mentoring younger girls from the time of their first period. Can you talk a little bit about the role that older women played in younger women’s lives?

BT: Yeah. Reproduction is generally quite sex segregated. Generally speaking, it was understood to largely be a women’s realm, women’s space. What you see is a lot of intergenerational transmission of knowledge in which elders, and often a grandmother, play an important role. And then when it comes to childbirth and actually giving birth, it was a somewhat flexible system in which often there was an elderly woman, a mother, a grandmother in the woman’s family who would help, who had extensive midwifery experience. But it was also not uncommon for them, especially if it was a somewhat difficult birth, to bring in a community member, an elderly woman who was widely respected as a midwife, for the extensiveness of their experience. And this knowledge came again through experience and doing this again and again. So often what it looked like, if you look at oral histories, it is something of an apprentice system. If a young woman was interested in this, or maybe if one of her mothers was a midwife, they would start to be present at these births. And it was really then after a woman gave birth herself, that then those in her family or in her community might start to look to her as a midwife in childbirth. And so if you look at the 19th century, they would construct a makeshift lodge or a teepee for this particular birthing space, and that was understood to be women’s space.

AA: Yeah, it’s really beautiful. Can you talk a little bit about how unwanted pregnancies were viewed and dealt with among the Crow?

BT: Yes. At Crow, both Crow sources, so a lot of oral histories, and also non-Crow, Euro-American sources like ethnographers’ writings and what physicians at the time were writing, they’re pretty consistent in emphasizing the woman’s prerogative in making decisions. And also in recognizing at least some elder women’s, especially midwives’, skills in terminating pregnancies that were for various reasons deemed undesirable. Again, think of 19th-century Montana and those winters. So that could be because of material circumstances, that could be because of the mother’s health. That’s one of those things that’s kind of difficult to to get a real handle on so far after the fact, but those are reasons that come up in oral histories.

And these women had quite a bit of bodily autonomy for making those decisions. And that also I think points to something important to understanding when we’re talking about midwives, is that their knowledge and expertise was not just surrounding childbirth itself. They had a whole range of knowledge. And some had different areas of knowledge and expertise as well. So many midwives, at Crow especially, were recognized as being particularly skilled at handling colic, when infants had colic. I won’t attempt the Crow word, but there’s a kind of a word for a “colic doctor”. And what’s interesting is that even as aspects of this knowledge were disparaged by colonizers, this knowledge surrounding colic was passed down throughout the 20th century. And there are still community members who are recognized for their prowess in dealing with colicky infants.

AA: The baby whisperers of the community.

BT: That’s right.

AA: That would have come in so handy with a couple of my kids. Okay, there were so many beautiful details in the book. One that comes to mind is that it was often a grandmother who would cut the infant’s umbilical cord. And that was a really big deal cutting the umbilical cord, right? And they would save the umbilical cord and she would pierce the child’s ears. Those were very tender details to imagine and to think of, again, how it’s a very human thing to think about your own mother and her relationship with your baby. It’s so beautiful. And it was really neat to me too, to read that the father’s side was involved as well. They would usually give blessings and contribute the cradle board for the baby, right? That was such a lovely detail.

BT: So reproduction is a really important moment for the codifying of and concretizing of these clan relationships that are going to be so important. And also of binding together the mother’s clan and the father’s clan in the care of this child. It’s just beautiful.

AA: So let’s move on then to some of the changes that started to happen as Euro-Americans started to influence specifically the Crow Nation, which you talk about in the book. One general and foundational concept that I thought was really important and heartbreaking was this one, and I’ll just read a quote from the book:

“In settler colonial societies like the United States, Canada, and Australia, among others, the principal objective of governments and settler citizens is the acquisition of land for permanent occupation and dominion. And Native women’s bodies had long been on the front lines of white Americans’ often brutal quest for Native land.”

I wondered if you could talk about, in general, settler colonial societies and the connection between their view of land and their view of Native women’s bodies.

even as aspects of this knowledge were disparaged by colonizers, this knowledge surrounding colic was passed down throughout the 20th century

BT: When you look at this, especially globally, there are all sorts of different ways that settler societies at various times, and often this changes over time even within a given society, tried to bring about the elimination or the disappearance of indigenous peoples. And so that has at times been through brutal genocidal violence and military conquest. It has been through ethnic cleansing, when you think about the removals in the Midwest but also most famously in the Southeast, just moving them out of there. And then later, as we’ll talk about, once they’ve been militarily subdued, the type of elimination or disappearance is less physical because they’re now believed to be in relatively contained numbers and relatively contained spaces of reservations. Those really emerged, especially in the West, in the 19th century.

Then it’s about eliminating indigeneity from a cultural standpoint. So that’s where you see campaigns of cultural assimilation. The famous quote that really gets at the heart of this is from a military man who transitioned into being a prominent assimilationist. And what he said was to “kill the Indian in him and save the man.” So no longer talking about killing Native peoples physically, although he had been engaged in that effort, but rather eliminating all that was understood to be “Indian” about them. And my book picks up right where those assimilationist campaigns began, right when the Indian Wars were winding down in various ways and these assimilation efforts were taking off. They weren’t brand new then, but they were really coming to the fore.

So where do women’s bodies and women fit into all of this? I think in a few different ways. One, is that one can understand if you’re thinking almost theoretically about settler colonialism and the impetus toward Indigenous disappearance, women’s reproductive capacity is potentially a problem. And it’s something that is not necessarily welcome. So there was a lot of violence against Native women, especially in the stages of colonization that were particularly physically violent. Certainly, Native women were targets of sexual violence, as Indigenous feminists have written quite a bit about. And that actually has dark and unsettling ties up to the present with phenomena like missing and murdered indigenous women and girls.

But the other way that you see this, when the assimilation efforts take off, is more about thinking about Native women as mothers, often as bad mothers, inadequate mothers. Certainly inadequate for raising those who are supposed to be future American citizens. So women and mothers became really central to discourse justifying various forms of removal of indigenous children, and also just a real effort by proponents of assimilation. To really reform families and the gender relations that are implicit within them. So often that meant a real, notable decline or diminishment in women’s roles, and especially elderly women’s roles. Because there’s a real marginalization of elders because that level of elders’ centrality to daily life did not have a corollary in contemporary Euro-American society.

AA: Yeah, absolutely. Well, let’s talk more about that. Let’s talk some more about the ways that the reservation system and the assimilation efforts disrupted the family structure and reproductive practices of the Crow. One of the bullet points that I remember from the book was allotting agents issuing allotments to men as heads of households, which facilitated this patriarchal shift away from matrilineality, away from the communal, egalitarian structure that had existed before. Punishing couples who were living together without being married. And one thing that you talked about before too, was with Crow loving to share children and that Europeans just did not understand that. And if one family was seen to have adopted another child, they saw that as “an evil” and they said that “this is an evil that we have completely stamped out.” And prohibiting abortions, there were just so many disruptions of their way of doing family. Can you tell us about some of those that were standouts for you? And then I especially want to talk about moving childbirth from the home to the hospital.

BT: Absolutely. So with allotment, this is a policy that is best reflected in a piece of legislation passed in 1887, the General Allotment Act. And basically it was premised on this idea that communally held land was a real problem, and that for Native peoples to become industrious and assimilate into modernizing American society, they needed to embrace private property ownership and a pursuit of individual interests, and that private property would help with this. And not all Indigenous nations were allotted, but many were. This did happen at Crow. Basically, the surveyors went out and divided reservation land into plots, often of about 160 acres, that would then be assigned to individuals. And the idea was that these individual plots would be farmed within nuclear family units. And I have to give a shout-out to Rose Stremlau here for her work on the history of allotment, but also about how indigenous peoples resisted allotment in all sorts of ways and how indigenous kinship foiled a lot of the grand plans surrounding allotment, at least in certain cases.

And one of the things you mentioned, that at first they said married women would not get a separate allotment because of this male head of household, right? We are kind of imposing coverture, that the woman’s property is just through the man by proxy. But that eventually changed. Really quickly at Crow, even the folks who were trying to implement this were saying this is totally unworkable because their conception of marital unions are quite different. So marriages were breaking up too quickly and it just was not working. So that actually did change because it proved so incompatible with what was going on on the ground. So there’s examples of those types of disjuncture that are quite fascinating.

And in the early 20th century at Crow, this new superintendent– and for folks unfamiliar with Native history, that term might not make any sense, but a federal agency, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, was charged with managing Native reservations. And there were Bureau of Indian Affairs employees, so government employees, on each reservation with particular responsibilities. And at various times they were called an agent or a superintendent, and at Crow they called him the “boss man”. So he really represented the power of the colonizer. I mean, he had a lot of disciplinary power, as you suggested, into really intimate spheres. If a man and woman were living together, cohabitating without a legal Christian marriage, they could be subject to punishment. The sharing of children, as you mentioned. There was a “rightful home” policy in which the superintendent’s expectation was that children live with their nuclear families, their biological parents. And there were all sorts of mechanisms to kind of coerce this or enforce this.

So missionaries started a Baptist day school, which Crow parents very much wanted because if their kids went to day school, then they didn’t have to go away to boarding school. So they wanted this, but the school would only enroll students who were living in their “rightful home”. So those are the types of choices that were imposed on them. But you quoted that superintendent from early in the 20th century who said something about this “evil that we have stamped out.” And why I find that so interesting is because there are a couple possibilities. One is that he is writing this to his boss, so he is putting forward a very authoritative, victorious front. Or he thinks this is the case, but if you look at Crow sources, there seems to be no change whatsoever. I mean, there probably was, but there are all sorts of examples from oral histories where there’s this real mismatch between what you’re reading in the official government record and what seems to be happening on the ground. And again, that’s why I think it’s so important to have this case study, or local view, so that we don’t just assume that if something is policy that this is how it went for people. But there are all sorts of ways that folks resisted, negotiated, and accommodated all sorts of policies.

AA: Oh, that’s good to know, actually, that it wasn’t as completely eradicated as perhaps was indicated. Though it certainly indicates their attitude toward it, I guess. Can we talk a little bit about the reproductive practices of abortion? That was prohibited starting in the 1870s, I believe. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

BT: In the mid to late 19th century, there was a cohort of folks, especially physicians and medical practitioners, who really pushed for the criminalization of abortion. And there were different reasons for this, but it gets to the point I said earlier about women’s authority and prerogative. Previously, in most cases abortion was not criminalized before quickening, so before the mother could feel the infant, which of course puts a lot of prerogative and also knowledge and authority in the woman. Or kind of recognizes that knowledge. And so part of what this criminalization does is it shifts the authority with regard to pregnancy. So what you see in the 19th century is state by state criminalization of abortion. And so in Montana Territory, I believe it was 1879, abortion was criminalized. The impact that had at Crow in the short term, I suspect it was quite minimal. Though certainly the messaging from missionaries and others surrounding the evil of abortion, Crow started to encounter that I think with greater frequency in the 19th century. And then by the 1930s, I found in some oral histories references to Crow women having become fearful of abortion for fear of legal repercussions by the settler state, for pre- and post-coital birth control.

there’s this real mismatch between what you’re reading in the official government record and what seems to be happening on the ground

AA: It just strikes me as you’re talking, again, this is how I felt as I read the book. Putting myself in their shoes, imagining my own life and the things that I listed at the top of the episode, like a baby shower and the way that I told my family that I was pregnant. If there were a colonizing power that came in and took over my country and my community and then started making laws about what I could do regarding my own body, my relationship with my husband, my relationship with my mother, there’s just nothing more personal than your family and like the reproductive parts of your body and the little children that you’re raising. It infuriates me to think about what that would actually feel like to have some foreign power come in and not only make macro level laws about the way that we would operate in the public realm, but in the most private realm to meddle with that just makes me furious. And it’s so inappropriate, especially for a group of men to do that to any group of women. But to come across the ocean and make laws where they just do not belong, it just hit me anew as you were describing it.

BT: Yeah. And I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, and maybe a lot of folks have, with the recent Supreme Court decisions around Dobbs. And one of the things that I think about a lot with regard to Dobbs is that there is this kind of irony or tension, or I guess it’s like a paradox because two things are true. One is that this is something that Native women have emphasized for a long time. Roe v. Wade was never really a reality for many Native women. The constitutional protections, limited though they were, that existed for many women were sort of circumscribed in really important ways for Native women, most directly, I think, through the Hyde Amendment, which was passed a few years after Roe v. Wade. It prohibited the use of federal funds for abortions. And the reason that’s particularly important for Native women is because they receive their healthcare through a federal agency. So that’s all federal funds. It’s basically saying that their providers, definitionally, cannot do this.

And so it is simultaneously true that in many ways, Roe was illusory for Native women. I find that so aggravating and painful as a continuation of what you just so eloquently described. We see the evolution of those dynamics. So that’s true. And then at the same time, it’s also true that Dobbs presents unique and particular hardships for Native women as well. For Native pregnant people more broadly, because of the pre existing constraints. And now there’s this new level of constraint for women, at least in certain states. And of course, many reservations are in rural areas, many are in conservative states. So once you start tracing some of these politics surrounding abortion, for example, there’s a real resonance in the present for so many of these policies and politics.

AA: Can we talk about the rise in infant mortality after these disruptions started to happen in childbirth practices like moving childbirth to the hospital? There are so many disruptions that happened, there was a big rise in infant mortality. Can you tell us about that a little bit?

BT: One place to start is that the transition to these early reservation systems was a public health disaster in so many different ways. Folks were confined and forced to live a more sedentary life. If they wanted to leave the reservation or even leave a district in the reservation to hunt or whatever, they needed a signed pass by the boss man, the agent or superintendent. So it was a more sedentary lifestyle cut off from a lot of forms of economic life and sustenance. This is also a time when, at least in the plains, the buffalo, bison were disappearing, and that was not an accident. There were real problems with malnutrition. The rations that many groups were promised through treaties proved inconsistent and unreliable. There was also, in some places, a lot of corruption that led to that unreliability. So hunger was an issue. This led to diseases of poverty, so tuberculosis, trachoma, a really serious eye condition was prevalent.

And then what’s often the case, as public health folks realize, is that infant mortality rates are useful as a pretty sensitive indicator of a community’s health more broadly. And in a way, it’s a little bit hard to talk about a rise in infant mortality, which I think there certainly was, it makes all the world when you think of the public health context, but because the early 20th century was when infant mortality rates were becoming a way of calculating and measuring child and infant welfare, thus community health, in different communities. So the United States was learning, first of all, that actually they were lagging behind much of the world, certainly among developed nations, when it came to infant mortality and maternal mortality. But also internally, that there were all of these different racial and regional disparities in infant mortality. So at Crow, to give you a sense of the scope when we’re talking about these public health disasters, more than one third of the documented tribal population died in the 1890s alone. So in a single decade. And again, youth, infants, children, were disproportionately impacted which is to say that youth had disproportionately high morbidity and mortality rates. Which, if you broaden the scope a little bit, is going to have longer term implications for community population and reproduction. So part of what you see at Crow then is a response that is an increase in birth rates. So only extraordinarily high birth rates really kept Crows alive and ensured the survival of the nation. And if you look at some contemporary sources, that’s how they were talking, the survival of the nation and the people moving forward.

So then, there was a situation in which Native women, Crow women, were increasingly malnourished, more likely to have tuberculosis, dealing with the health challenges that were endemic to their reservation at the time. And also, in many cases, they were bearing more children, which is, of course, physically taxing. So that’s sort of the health situation going on at Crow. And increasingly, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and government officials were recognizing that comparable things were happening on reservations certainly throughout the West. And so what that led to was a greater recognition. This is a time when nationally, women’s organizations and even governments were starting to pay a lot more attention to infant and child welfare. There were these progressive era movements around pro-natal campaigns. And so we start to see some of that playing out on reservations and the need to combat this high Indian infant mortality. This “save the babies” campaign, so pro-natal efforts that were often highly assimilationist.

It’s in the context of this sustained attention to infant mortality, especially in the 1910s or so, that part of the solution is this push for hospital births, which was, I think, well intentioned. I mean, certainly assimilationist, but I think that the folks advocating this did think that this would be better for birth outcomes. And there were certainly some prejudicial perspectives of why they thought that. Of course, we know from a historian of reproduction standpoint that actually the hospitals more generally weren’t able to meet this promise of better health outcomes and certainly of less infection, fewer complications until the 1940s. So there was actually an increase in maternal mortality, and here I’m talking nationally, not just on reservations, but that corresponded with the shift into the hospital. But I don’t think that wasn’t fully recognized at the time by most folks.

AA: One thing that was also so frustrating to read is how they blamed mothers for poor health outcomes in their babies. One thing that I recall was kind of the back and forth on infant formula, how at first they shamed Native mothers for breastfeeding because it was seen as backward. But then they realized that the Native mothers couldn’t access enough formula so then their babies weren’t thriving. And so then they were shamed for feeding them formula. Can you talk a little bit about that specifically, and some other ways that women were seen as ignorant and shamed for their mothering practices?

BT: Yes. I mentioned my dissertation earlier, which was more policy history. But what I titled that, which was way too long of a title, was ‘The Simplest Rules of Motherhood’ and then there’s a colon and a whole bunch after that. But ‘The Simplest Rules of Motherhood’ is a quote from one of the commissioners of Indian affairs in the 1910s, and he was one who, he didn’t start the so-called “save the babies” campaign, but he’s the one that really ramped it up and put a lot of attention and some resources (still quite limited) into this. But he said something in both his speech and in his writing about “the simplest rules of motherhood” would save all of these babies from their untimely graves. And so part of the task then was to teach these simplest rules of motherhood. And this is where we see these rules being about hygiene and sanitation, and basic nursing, and about the arts of homemaking. And all of these domestic and kind of assimilationist lessons all blended together.

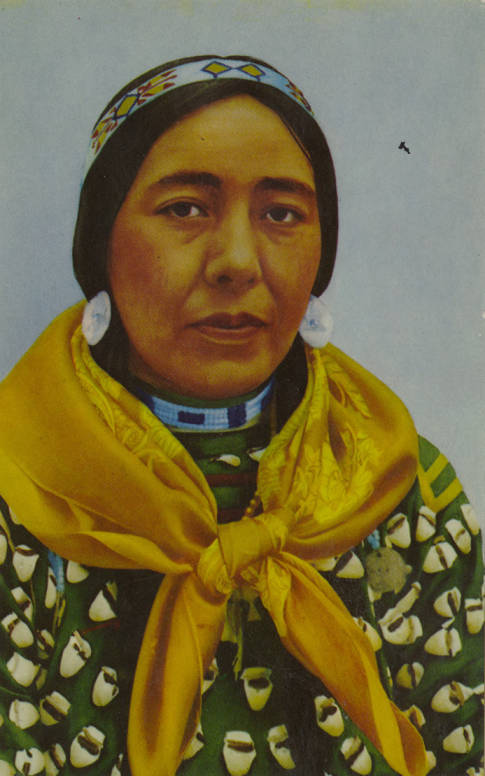

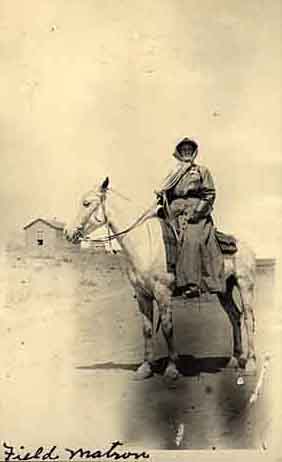

But how that happened, or how it was supposed to happen, was that the federal government, starting in 1890, hired mostly white women and sent them to these reservations. They were called field matrons. And what’s interesting about this is, especially from the 1890s and well into the 1920s, the folks who were hired for this did not necessarily have any qualifications besides being a white woman who was assumed to have this more innate, maternal knowledge that they could impart. So, sometimes through missionary networks, there are all sorts of different ways, but these were not folks who necessarily had any training or credentials to speak of. That started to change especially in the 1920s when there was a shift from the field matrons program that started in the 1890s to trained public health and field nurses. So that transition started to happen in the 1920s, but there was a long time when it was the idea that Indigenous women, Indigenous mothers, are deficient. And so we’ll bring these white women in and they will teach them the simplest rules of motherhood.

And I also found all these references to teaching them the importance of taking an interest in their babies and raising their babies. And it’s really interesting because when you read the record, it reads so much like apathy. But often it’s fairly clear that what’s happening, if you have a sense of the larger context, is that it’s often not the mother who is the most involved in daily care because it’s more collective, because the grandmothers have this role. So part of that was that those constant references that furthered these associations with apathy and negligence were also evidence of continued efforts to reorganize families and systems of care within families.

AA: They’re trying to fix problems that they themselves created. We have time for maybe one more topic. And you mentioned this before, that there’s this back and forth between real efforts at extermination and then “wait, no, we want to save the babies. Now we want to have everyone assimilate and kill the Indian in the person.” It’s just this back and forth. It was really frustrating and disorienting and awful. But the last thing that I wanted to ask you about was this campaign of forced sterilization. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

BT: Yes. When I started this research, I was struck by how little scholarship there was about the history of reproduction. But what did exist, what I was aware of, was a handful of articles about this pro-natal campaign that we’ve been talking about, the “save the babies” campaign. And then there were a handful of good articles and especially master’s theses about coercive sterilizations in the 1970s. And so those are the two bookends that piqued my interest both in unsettling ways, but that I felt like we needed to know more about. And so, I started looking into coercive sterilizations. And there’s probably a range of opinions about this in terms of how folks interpret the historical record on this. I actually wouldn’t use the language of campaign, because I think that implies a level of coordination that often didn’t exist. And I don’t say that to diminish at all the severity, I just think it’s important to understand how this actually functioned. And in some ways it was more insidious because it was a lack of policy. It was a lack of protections, a lack of safeguards. It was a lack of response to abuse. And it’s a reflection of the often tremendous discretionary authority that individuals have on the ground. So individual physicians, also sometimes social workers.

And I came to understand how important that was in part because that’s what some of the Native women who actually experienced this, that’s how they talked about it. He’s talking about the power of certain doctors, where they’re kind of forced to go to the government hospital on their reservation and then they have limited power as patients. So I was somewhat aware of real concerns about sterilization abuses in the 1970s, and this is a time period where Latina women, Mexican American women, Puerto Rican women, African American women in different regions were voicing similar concerns and were in some cases joining together in coalitions to end sterilization abuses and to put into place some tangible protections for folks. And that actually did happen. It didn’t solve everything, but there were some new federal guidelines put in place in 1979.

But one thing that emerged in the course of my research that I was not expecting, and that I think most scholars of Native history were not expecting, is that coercive sterilization was not so new in the 1970s. I mentioned Susie Yellowtail earlier, who was a really incredible Crow woman, a registered nurse, a mother, a grandmother, very active at the tribal level with regard to health. And then with regard to indigenous health more broadly. And I discovered that in the 1930s, she was sterilized without her knowledge by the government physician at the hospital on the reservation. She was really upset about it. She talked to an interviewer later in her life, just before her death, actually. She used words like “devastated” and “outraged”. And she also reported, which government records largely confirmed, that this was happening to other folks at the time as well. And so you see a whole bunch going on here. If you look at Crow in the 1930s, for example, you see the impact of eugenic language and logic being utilized by folks on the ground, by physicians and other authorities. So that’s a lens through which they’re understanding what they deem social and economic problems on the reservation. Also that point about the tremendous discretionary authority for physicians on these somewhat remote, at least remote from power, government power structures.

The physician whom I believed sterilized Susie Yellowtail, for example, he’s on record when he moved to the reservation saying that he was hoping to perform as many surgeries as possible because he was trying to qualify for acceptance into a particular medical society, the American College of Surgeons. And because of those experiences, Susie Yellowtail was really attuned to those dynamics and was really outspoken about the ways in which Native bodies and Native institutions have often served as teaching institutions, right? And bodies as kind of the guinea pigs on which folks learn and experiment. So she talked a lot about that, and in a few different published forums in her life as well.

she was sterilized without her knowledge by the government physician at the hospital on the reservation

So the reason that I qualify the campaign language is because I think understanding how these power operations worked is really important. And one of the things that you see in the 1970s is a really astonishing lack of oversight. The federal government was subsidizing sterilizations starting in 1970 for IHS patients and for Medicaid patients. So footing a lot of the bill, and according to the language of the law, these were supposed to be voluntary procedures. And in some cases they were, though I think it’s important to recognize the ways in which limited choices delineate the parameters of choice. But they were paying for them and saying that they should be voluntary, but there were no real safeguards in place. So again, that’s something that started to change in fairly tangible ways, though imperfectly, in 1979.

AA: Wow, it’s just excruciating to hear about it. To wrap up, I’d love to have you talk about the follow-up to that period of time and what happened in reproductive justice after 1979. Is there any good news?

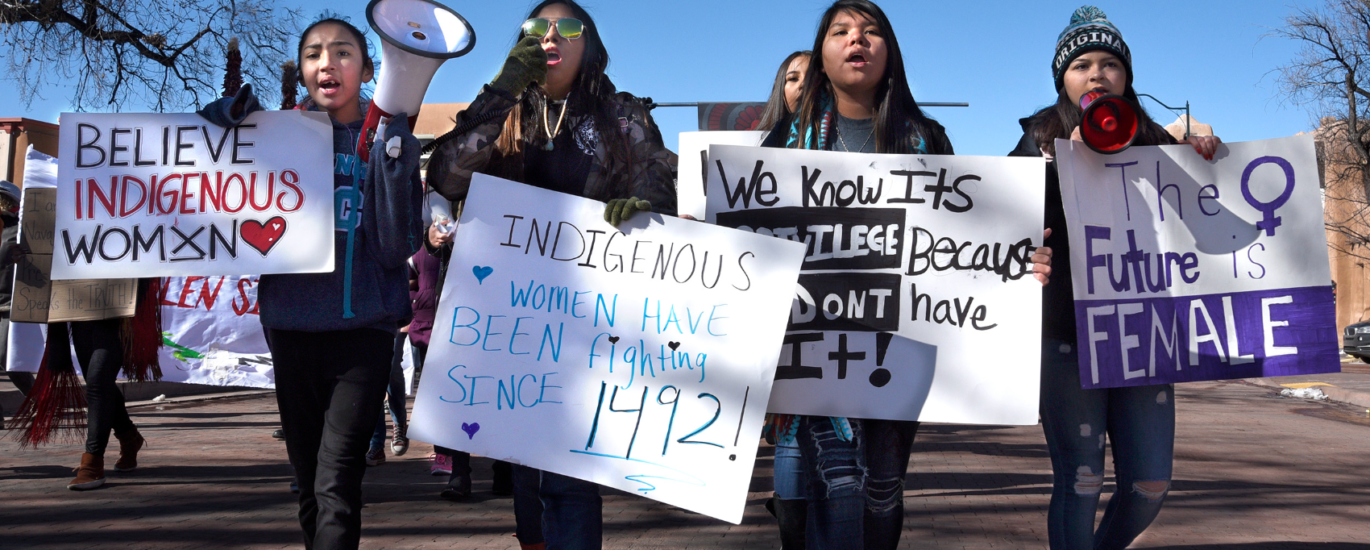

BT: Yes. I think it’s important to recognize that across the entire span that I’m talking about, Native women organized in various ways, whether they considered themselves activists or not, and understood their work as such or not. But they organized in various ways around reproduction. And then building on this more localized work, in the 1970s in the context of some of the reproductive abuses and injustices that we just talked about, that was a really important moment for Indigenous organizing more broadly, and Indigenous women’s organizing specifically. My book actually opens with the first meeting of a grassroots group, an Indigenous women’s organization called WARN, or the Women of All Red Nations. And they were one of many groups that, first of all, fought against sterilization abuses, but also advanced a really wide ranging reproductive agenda.

And like Black feminists at the same time, they were really important in understanding both in their organizational work and also theoretically that reproductive issues are more broad than just abortion and birth control. It includes sterilization politics. So the right to be able to have children, a right that’s been denied to women of color and poor women at various times historically. And also the right to parent children in safe, healthy, sustainable homes. Those are the three tenets. The right to have children, the right not to have children, the right to parent children in safe, healthy homes. Those are the three tenets advanced by Sister Song, which is a leading women of color-led reproductive justice organization. It was started in the 1990s that Native women were part of that multiracial effort. They still are.

So there’s a lot that’s happened at the policy level, of course, up to the present. Some of which is good, much of which is continually frustrating. The levels of federal neglect, I would say, in terms of funding for health institutions. So at Crow, for example, there no longer is an obstetrics department. It closed because of funding issues back in 2011. And despite Crow women’s efforts to be able to once again give birth on the reservation, they’re still having to drive a few hours. And that’s happening on a lot of reservations, as it is to some extent in rural areas more broadly. So for me, thinking back about the last half century, it’s the importance of different grassroots organizing surrounding reproduction, reproductive justice, attempts to decolonize childbirth as part of a broader initiative of cultural revitalization and language revitalization. And for so many people, these things are interconnected.

So I really appreciate, for example, the work that the Changing Woman Initiative is doing right now in the Southwest. Indigenous Women Rising has been such an important organization, especially post-Dobbs, they provide funding for Native people who are wanting to obtain an abortion and now maybe have to travel quite a distance to do so. But they also, importantly, provide funding for Native people who want to secure midwifery services, midwifery care, during and after pregnancy. It’s a multifaceted approach to reproductive health and wellness. So there is a lot of really exciting work going on surrounding Native reproductive justice. And I think it’s building in really important ways on, certainly earlier generations, and maybe on that moment in the 1970s.

AA: Fantastic. Well, we’ll have all of these organizations and initiatives listed on the website for listeners who want to get involved and maybe make a donation. And if you want to learn more, again, I highly recommend the book, Reproduction on the Reservation: Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Colonialism in the Long Twentieth Century by Dr. Brianna Theobald. I’m so grateful for this conversation, Brianna. Thank you so much for joining us.

BT: Thank you so much for having me, Amy.

where do women’s bodies

and women fit into all of this?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!