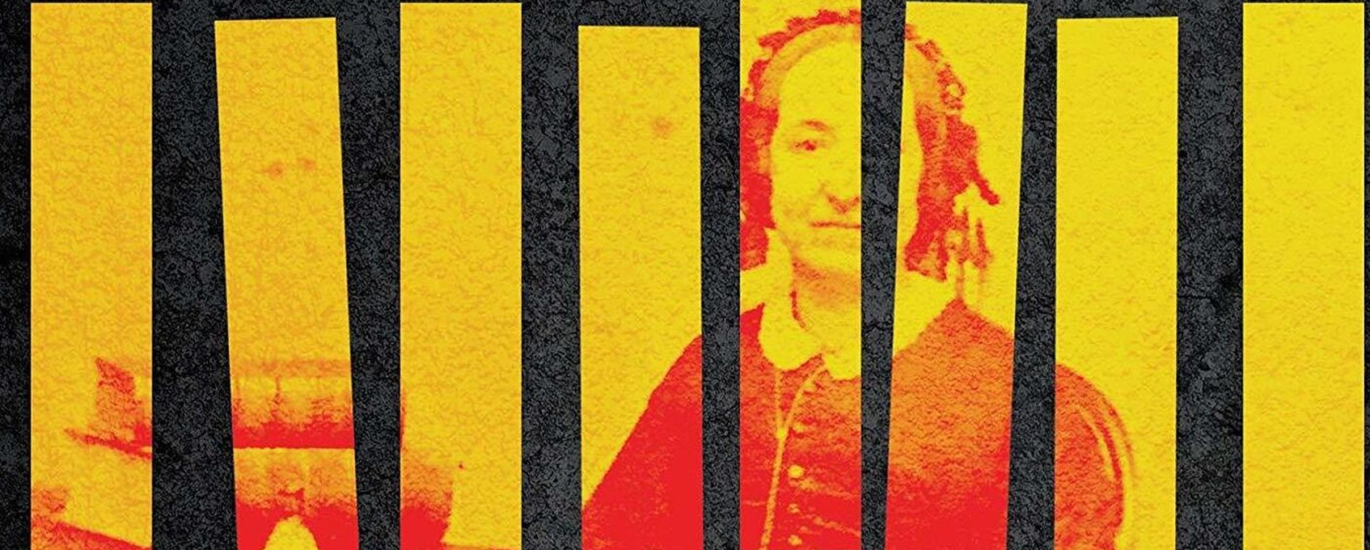

“she senses that they are coming for her, and they are”

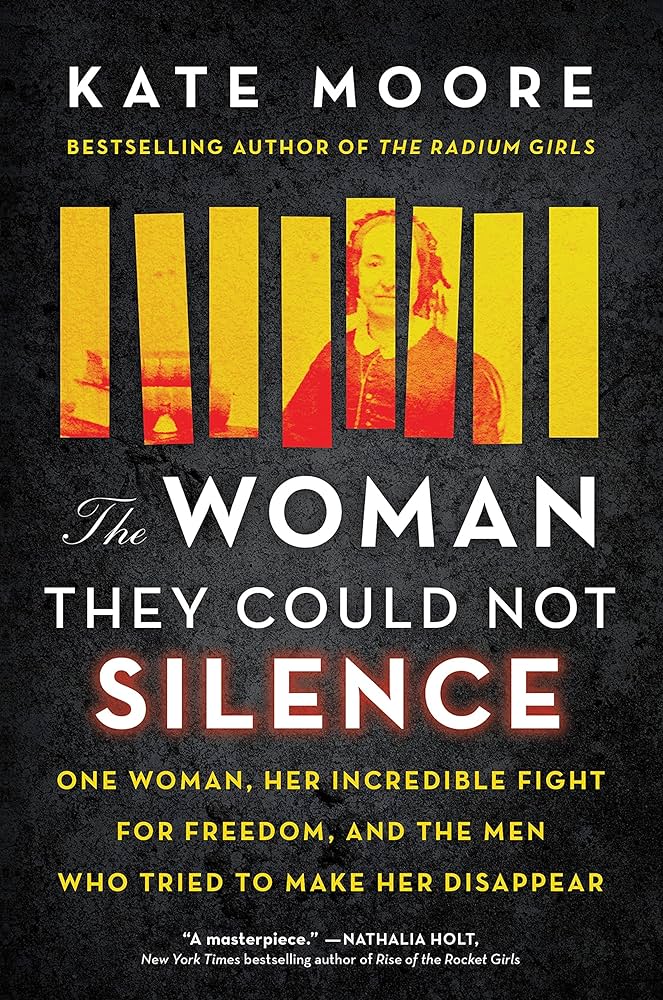

Amy is joined by author Kate Moore to discuss her newest book, The Woman They Could Not Silence, exploring the story of Elizabeth Packard’s abduction into an asylum, her triumphant fight for justice, and how mental health is wielded to discredit and silence women.

Our Guest

Kate Moore

Kate Moore is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of The Radium Girls, which won the 2017 Goodreads Choice Award for Best History, was voted U.S. librarians’ favourite nonfiction book of 2017, and was named a Notable Nonfiction Book of 2018 by the American Library Association. A British writer based near Cambridge, UK, Moore writes across a variety of genres and has had multiple titles on the Sunday Times bestseller list. Her latest book is the critically acclaimed The Woman They Could Not Silence, which, among other accolades, was named runner-up for Best History in the 2021 Goodreads Choice Awards and a 2021 Booklist Editor’s Choice.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: A few months ago, my sister and several other women in my life were reading the book The Woman They Could Not Silence: The Shocking Story of a Woman Who Dared to Fight Back by Kate Moore. One comment that people kept making is that you realize that if we had been born in a different time or place, we would have ended up in an asylum. This reminded me of a quote by Roxane Gay, and this is quoted at the beginning of the book: “Unruly women are always witches no matter what century we’re in.”

So I finally read The Woman They Could Not Silence, and I was astounded by this story. I wasn’t aware when I started the book that it was a historical book, that it was a true story, and I was just absolutely riveted the whole time. And I’m so excited to welcome to the podcast today the author of the book, Kate Moore. Welcome, Kate!

Kate Moore: Thank you so much for inviting me on!

AA: I’m so happy to have you here. I’ll just read your professional bio first and then we’ll ask you to introduce yourself a little more personally in a second.

Kate Moore is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of The Radium Girls, which won the 2017 Goodreads Choice Award for Best History, was voted U.S. Librarian’s Favorite Nonfiction Book of 2017, and was named a Notable Nonfiction Book of 2018 by the American Library Association. A British writer based in London, Kate writes across a variety of genres and has had multiple titles on the Sunday Times bestseller list. She is passionate about politics, storytelling, and resurrecting forgotten heroes.

So again, welcome Kate. I’m so thrilled to have you here. I wonder if you can start us off by telling us just a little bit about yourself, where you’re from, your education, your work, and the backstory of this book that you wrote.

KM: Sure. Well, as it says and as you can hear in my voice, I am British. That’s where I was born, where I grew up, and still where I’m living and working today. I have the joy of coming to America for research trips because I seem to be writing a lot about American history, which is wonderful. And then I take all the little nuggets that I’ve gathered up on my American research trips and I take them home to my study and immerse myself in the world of whatever book I’m writing then. My background is that as a young girl I was passionate about writing, reading, and theatre. I grew up to study English at the University of Warwick and went on to have a career in publishing as a book editor. And then from that rose to become an editorial director of Penguin Random House in the UK and left to go freelance. And originally I thought I was going to mostly be an editor when I went freelance, but I was actually lucky enough to be able to almost straight away support myself as a writer.

And I was doing all sorts of things. I was writing books that were my own ideas, I was ghostwriting for people. And a couple of years into that incredible new career as an independent woman, having taken that leap of leaving a corporate publishing job into being freelance and doing it for myself, I stumbled on this incredible story of the Radium Girls, these American women from the First World War and the roaring twenties who were poisoned by the radioactive radium paints that they were working with to paint clocks and dials to make them glow in the dark. They were taught to lip-point, which means they were putting their paint brushes between their lips with every dial they painted. And the paint obviously poisons them and they embark on a landmark fight for justice to hold the companies responsible.

I discovered it through a play. As I say, I’ve always been passionate about theatre. Even through my publishing career I kept acting, and this was the second play I directed. I found this script about the Radium Girls, fell in love with it, knew it was a true story, and I wanted to make my theatre production authentic. I read everything I could find on the women and there was no book that was about the women, about Catherine Donohue, Grace Fryer, the individual heroines and their story and their personal triumphs and tragedies. And I’d fallen in love with these women and felt passionately that they truly deserved a book that was dedicated to them, that told their story in their own words as much as possible.

It’s incredible having been a ghostwriter before I became a historical writer because I feel that what I did with The Radium Girls and what I did with the book we’re talking about today, The Woman They Could Not Silence, is that I almost feel like a ghostwriter for these historical characters. My research involves tracking down their letters, their memoirs, any books that they’ve published, any interviews they’ve given, and then drawing on their first person words. The words that these women themselves have put into the world about their experiences. And I stitched them into this narrative that hopefully reads in a very novelistic way. Even though I’m writing about history it shouldn’t feel dry and dusty and 160 years ago, it should feel like it’s happening to a friend right now, and you don’t know where the story is going to go, and she doesn’t know where the story is going to go, and we’re walking in step together on that journey to discover it.

So Radium Girls happened, I decided I was going to write the book that I couldn’t find. It became this New York Times bestseller and this incredible journey that I’ve been on since. And The Woman They Could Not Silence is the history book I wrote after The Radium Girls.

And the genesis of the book is really topsy-turvy. Because people obviously say it’s about one woman, this woman they could not silence, a woman called Elizabeth Packard. And people often think, “Well, you must have found her story and decided to write it.” But it didn’t actually work that way. I actually decided on the theme of the book before I had even heard of Elizabeth Packard’s name. And I was inspired to write the book because of the #MeToo movement in the fall of 2017. What I found fascinating and striking about that time is that it was the first time women were believed when they spoke up about these issues of sexual harassment, misogyny, etc. It wasn’t that it was the first time women had spoken up, because women have spoken up for decades, centuries. It was the first time we were listened to and believed.

And that got me thinking, why had it taken until 2017 for that to happen? And one of the reasons is that historically, whenever women have used our voices, we’ve been called crazy. Our mental health has been wielded as a weapon against us, used to undermine us, to discredit us, to silence us. And I decided that’s what I wanted to write about. And to do it, I didn’t want to write a polemic because what I do best is to tell a story. I’m a storyteller. So I went looking for a woman in history, a sane woman, who had spoken up, who had stuck her head above the parapet, who would have been labeled insane for doing so. And what I crucially wanted in this woman, because there’s lots of women in history to whom that has happened, I wanted a woman who had somehow prevailed against the patriarchy, who would somehow manage to prove that she was sane despite all the accusations against her and whose story had a happy ending. Because that’s what I wanted for my book.

And I went looking for Elizabeth, but I didn’t find her at first because I started in the 20th century. And in the 20th century, women who were called insane were not only locked up in asylums, but they were subjected to electric shock therapy treatments or lobotomies. And those women generally were silenced forever because they were irreparably harmed by the treatment they experienced, so I looked further back before those treatments had been devised. And it was in January, 2018, I’d fallen down this sort of rabbit warren of internet searches about women and madness, and there was this random essay that I found online from the University of Wisconsin about lunacy in the 19th century. And four pages into that student essay there was a single paragraph that mentioned the name Elizabeth Packard, and very quickly I knew she was the one.

AA: That’s amazing! What a great story. So you had one line, you saw her name, had kind of the tingly feeling of like, “Oh, it’s fate! I found her!” And then how did you go about your research? Because there’s so much material to work with, right?

whenever women have used our voices, we’ve been called crazy. Our mental health has been wielded as a weapon against us, used to undermine us, to discredit us, to silence us.

KM: So much material. Well, it was literally that same night that I first read her name in that essay, I then obviously Googled Elizabeth and fell down on rabbit warren all about her. And it was literally that night that I was like, “She is something special. I really think she could be the one.” I literally wrote it in my diary that night. “I think I found her.” I had to then do my due diligence. What other books are on her? Is there room for a book that I want to write? And so on and so forth. And I did all of that before finally choosing her.

But the thing about Elizabeth’s story for me as a storyteller and the kind of books that I write, it was such a gift because the story itself is amazing. You’ve got the gothic horror of 19th-century insane asylums that she gets carted off to, you’ve got courtroom drama because Elizabeth Packard is incredible at somehow securing a landmark sanity trial in which, as I say, that question of her sanity hangs in the balance. As I say, it’s got so much drama to it. And of course, at its heart, this is a story of a woman, a really strong woman, fighting against injustice that still resonates today. And it’s a story about a woman who herself is a storyteller. Elizabeth became a writer.

And actually one of my favorite things about her story is that, you know, the book’s called The Woman They Could Not Silence and it truly is her journey of becoming that silence. She starts the book as a housewife from 1860s Illinois. She’s married to a preacher husband and has been married for 21 years. She’s a mother of six, her youngest is just 18 months old as the story starts. And Elizabeth doesn’t write. She doesn’t have time, she’s got six kids. But as the story progresses, she learns to use her voice, that voice inside her head and her heart that we all have inside us but we can’t always let out. And she starts to see herself take shape on the page, so she becomes a writer. She starts keeping secret journals. And eventually she manages to publish these words that are inside her to leave her voice behind to become the woman they literally could not silence.

And so, as a historical writer, a writer trying to bring these worlds to life, trying to give you intimate insights into these historical characters, what a gift to have this incredibly talented writer literally sharing with me at every step of her journey what she was thinking, feeling, experiencing, seeing, hearing. It was such a treasure trove of material that I was able to find as I finally began my research into her.

AA: Yeah, that is a historian’s dream come true, right?

KM: Completely, yeah, completely.

AA: So many primary sources that you don’t have to make guesses about what they’re thinking and feeling, but that no one had done it yet! Yeah, that’s incredible.

KM: Exactly. And the thing about her story as well, it’s not just that Elizabeth herself put her words into the world, because she herself in her time was an iconic figure, she was nationally renowned. It wasn’t just her words I had. I had her doctor’s correspondence, I had her husband’s diary, I had reports from the asylum itself. They used to publish these biennial reports that gave intimate detail right down to what the women were making in the sewing room. The number of socks that they darned, the fact that the women in the asylum were forced to make their own restraining jackets. That’s listed in black and white in the statistics that the asylum itself publishes.

AA: Amazing. Well, let’s have you tell some of the story. Not all of it, because we don’t want spoilers for readers who will go out and buy the book, which I recommend. But can you start us off by telling us, I guess you did a little bit in terms of the setting of time and place, but maybe some foundational social constructs at the time, too, regarding gender, regarding the construct of marriage. And maybe also Elizabeth’s early trajectory and her way of thinking. Because she started out as a young woman really traditional in her thinking, right?

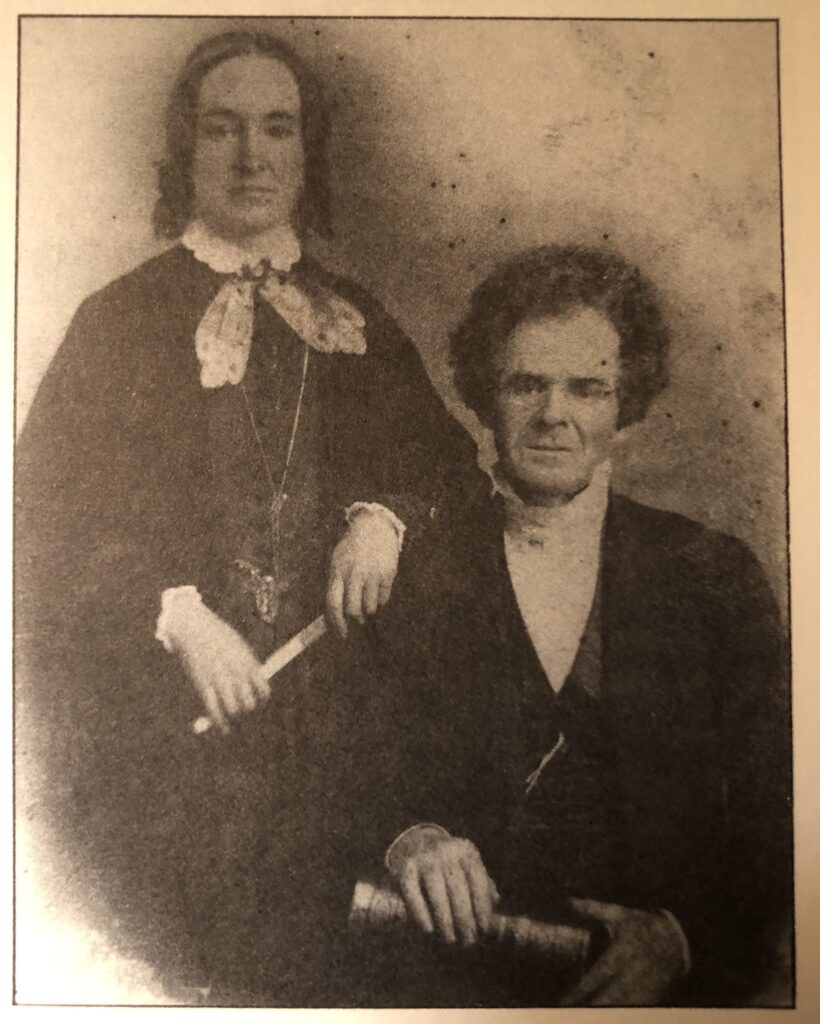

KM: Very much so. When she marries Theophilus, she is very much like, “I’m going to marry my husband. I’m going to be his helpmeet.” As she said, she was brought up to be a silent listener. She was there to absorb the male world and not put herself into the world and not use her own voice to speak about it. So, the book opens in 1860 in Illinois. Elizabeth has been married for 21 years. And at the time the book opens, the world is changing. Twelve years earlier, in 1848, we have the Seneca Falls Convention, which kickstarts the national conversation and the national movement for women’s rights. Elizabeth is very interested in that movement, and because she is, her husband actually says she’s becoming insane on the subject of women’s rights. It starts to affect every part of their marriage because Elizabeth becomes more and more assertive. Not just in the home, but also in Bible class that she attends, and again, she’s married to a preacher. She’s attending as the preacher’s wife, but she’s starting to question things and speak up and have a voice, and that is frowned upon as well.

And this is serious stuff in 1860s Illinois, because at that time, because of the marriage constructs that we’re talking about, it’s a time when legally a wife has no legal rights. When she marries her husband, her civic identity and her legal identity get subsumed within that of her husband’s identity. It says the husband and the wife are one, and that one is the husband alone. So it meant that wives had no right to property, no right to their own earnings, no right to the custody of their children, and literally no right to their liberty either.

On the statute books in black and white, it said that a husband could send his wife to an insane asylum simply by request. And specifically, and I’m quoting from the statute books here, “without the evidence of insanity that was required in other cases.” So a husband without any evidence of that insanity at all could send his wife to hospital if he just wrote to the doctor and said, “Please, will you admit my wife?” That was legally the situation. And a wife had no right to question that because she was, by law, her husband’s property.

AA: Unbelievable.

KM: So he could send her wherever he wanted, and ultimately that is what happens to Elizabeth Packard. She asks one too many questions and Theophilus decides he will not put up with that anymore, and he’s going to send Elizabeth away.

AA: Oh man. Do you think he really thought she was crazy? Was his expectation so much that any deviation from the standard male thought or his own personal thought, he really felt she was crazy? Or do you think there was something in him that was like, “No, I just have to get rid of her. Oh good, here’s a legal way to get rid of her.” What do you think?

KM: I think it was a bit of both actually. He was a man who had very traditional ideas. He was a man who was not curious in any way, he wasn’t intellectually bright, so he himself was kind of stuck within the limited cage of his own brain. So he wasn’t good at seeing other perspectives, wouldn’t countenance them. So he sort of had that disability, if you will, that he genuinely didn’t believe in what she was saying and thinking, how she was daring to question him, all of that he genuinely thought was mad. But I think also it was very useful that he could rely on these laws to get her sent away as well.

AA: Okay, so tell us what he did.

KM: So first of all, he gets his parishioners on side. He starts almost a kind of whispering campaign against Elizabeth, as I think still happens today. You drop a few hints that you think someone is mad and everyone else starts looking at that person in a different light. And so her community kind of turned against her. She describes it as “a pack of wolves that I had around my door and no gun to shoot them with either.” And they are watching Elizabeth and weighing her every action. And so something simple like Theophilus hadn’t cleaned the yard and so Elizabeth shouted at him, “Come on, what are you doing? You have to clean the yard!” But her neighbors witnessed that and this vision of an angry shouting woman who’s daring to stand up to her husband, who’s expressing emotion rather than being a docile, placid, quiet woman, that is cited in later documents as evidence of her madness.

The fact that she spoke up in Bible class, people talked about her incessant talking. And even in social studies today, there was one from 2018 that said that women who talk in an environment are perceived to be taking up more of the conversation and they actually are. Still to this day, women who use their voices are perceived to be talking too much. And that’s what happened to Elizabeth as well. So this incessant talking is cited as evidence of madness. And the final nail in her coffin is that she confides in a female friend from the parish that she dislikes her husband because he’s become very controlling. And this dislike of her husband is also seen as madness because she’s Theophilus’s wife and a wife surely should love her husband. If you dislike him, that’s evidence of madness according to what people thought at that time in the 19th century, when anything that deviated from the standard female model, the model of social acceptability, was seen as madness.

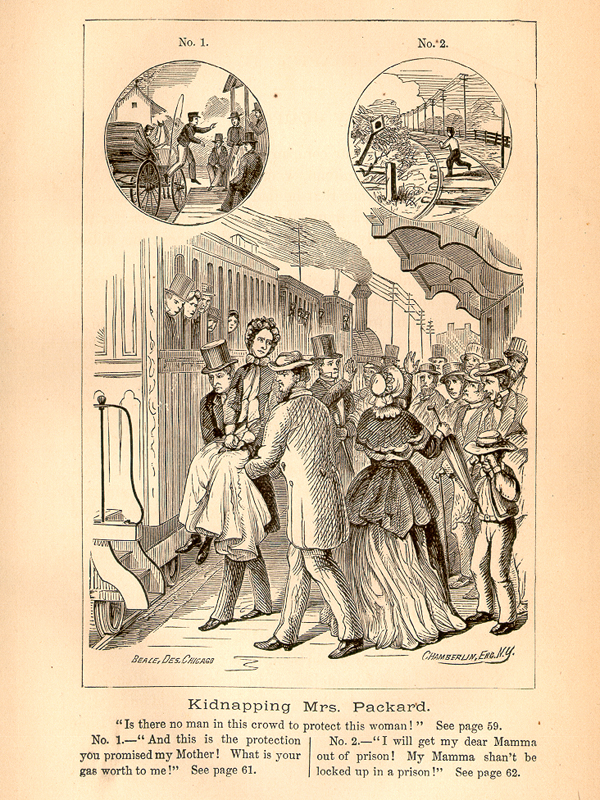

And so for Theophilus, he gets the parishioners on side, and then he writes a letter to Dr. Andrew McFarland, who is the superintendent of the Illinois State Hospital in Jacksonville, Illinois. And he applies to send his wife to the hospital and she is accepted as a patient. And so on the 18th of June, 1860, Elizabeth is rising in her bed and she hears noise outside, and she glances out and it’s her husband and four men. And she senses that they are coming for her, and they are. She locks the door, they can’t get in, they hack their way into her room with axes and carry her off against her will to the train station, where she is whisked away to Jacksonville. She doesn’t get a chance to say goodbye to her children, they’ve all been squirreled away surreptitiously so that she’s home alone on the morning of what she termed “the kidnap.” And she’s taken to the hospital, and on that hot summer’s night in June 1860, with her husband by her side, she climbs the stone steps of the asylum and she hears the door slam shut behind her.

AA: So tell us about the asylum itself. And you mentioned Dr. McFarland, the head of this asylum. Can you tell us about this new environment that she finds herself in and this person who’s in charge of her fate?

KM: Well, it’s a very imposing building. The state asylums were intended to be these grand houses on impeccable grounds. There’s an orchard, there are vegetable patches, and things like that. It’s supposed to be this heavenly environment where the patients are intended to relax and get well. The idea, of course, of the word “asylum” is that it’s a place of sanctuary. And that’s what you’re supposed to feel and think about as you first arrive.

The reality inside the walls is rather different. But at first, Elizabeth is very surprised when she first gets to the asylum. She wakes up the morning after she arrives and makes her way down the hall to the dining room, and she’s surprised because the tables are laid with cloths and the women are using crockery and glasses. It’s very civilized, there’s a hum of conversation, and she’s stunned to realize that the women around her on Seventh Ward are just like her. They’re middle class, they’re middle aged, they tend to be married, and they’re not insane. They’re just as sane as she is.

And having drawn on the doctors’ own notes from the era, these women have been sent to the asylum because they’ve caused annoyances to the family or defied all domestic control. And that’s why they’ve been sent away. They’ve been sent there to be, as Elizabeth put it, “to experience a subduing treatment.” The idea is that their spirit will be crushed from them, and the women will be recut as these paper dolls, all alike, all towing the same line. And McFarland, in his own writings, compared himself to Prospero. He was Prospero to the women’s uncivilized Caliban, and he was there to teach them and lead them. To teach them how to behave how society thinks women should behave in this world, so that he can say they’re cured of their insanity and send them back out to be obedient wives.

the women around her on Seventh Ward are just like her. They’re middle class, they’re middle aged, they tend to be married, and they’re not insane.

AA: So Dr. McFarland is aware on some level of the vast spectrum of women’s mental health that he’s housing within his asylum. Right. So can you tell us first about that spectrum? Because she first finds herself in the company, like you said, of women who are just like her. But she then realizes that there are other parts of the building where women are being kept who definitely do have mental health struggles. So maybe you could talk about the other women and then circle back to Dr. McFarland and what he knew about these women’s mental health.

KM: Well, as you say, there is a spectrum, just as there is today. Elizabeth is in Seventh Ward, which is seen as the most privileged ward. But as she starts to settle into the asylum, she’s actually given great freedom and she’s allowed to walk the grounds, and she hears other women shouting to her from the windows warning her about Dr McFarland, saying things are not as they seem, and she also hears these women crying and screaming at night. So she’s unsettled by all of this.

At this stage, she herself is kind of swept away by Dr. McFarland actually. He practices a kind of listening treatment, and I always think that for Elizabeth, the pressure that she’d been under at home, to actually get to the asylum, to suddenly be given freedom, to meet a man who, unlike her husband, McFarland was intelligent, creative, he wrote poetry, he quoted Shakespeare in his psychiatry essays, and he listened to her. She was kind of bowled over by him. So she’s unsettled by these things that she’s hearing and witnessing, and she’s also perturbed by the way that the women on Seventh Ward are treated as well. If they cry, if they grieve for the children that they’ve left at home, all of that is frowned upon, stamped upon. The women are supposed to be smiling and happy, and any emotion is seen as evidence of madness and those women may be moved to a worse ward.

AA: I’d love for you to talk a little bit more about Dr. McFarland and that relationship and how it changed over time.

KM: That’s right. It really is a relationship that evolves. As I say, when Elizabeth first meets him, she thinks he is a good, kind man, and an impressive man as well. I think she almost falls a little bit in love with him I think, bearing in mind that she’s come from a loveless marriage of 21 years with Theophilus, who is 15 years her senior, who, as I say, is not a curious man. He’s not intelligent, he’s not kind. I read his diary. This is a guy who’s a hypochondriac and he describes himself as dull, and he was. And to move from that to this world where she and McFarland can discuss politics and all sorts of things, she is a little bit swept away by him.

But she’s also concerned by what she’s witnessing in the asylum. And eventually, because Elizabeth is very much a go-getting person, she’s a doer in life, she’ll always roll up her sleeves and crack on with it, and she will always speak up for people as well. Obviously, part of the reason she’s been thrown in the asylum is because she is not cowed by “you shouldn’t speak up.” She will always speak up for the underdog, for those in need.

And so she decides that she will use her relationship with McFarland to argue firstly for better conditions for the other women and the other patients. She will raise these concerns that the women in lower wards are shouting to her. She’s going to speak to the doctor about that. And she also decides, after a couple of months of being there, that she’s going to bring up her own case. Because throughout the four months that she’s been there she has not shown the slightest sign of madness. She believes that McFarland doesn’t think she’s mad because she’s allowed such freedom of roaming the grounds and helping to look after the other patients. So she decides that she’ll use her relationship with him for the greater good. Her sisters on the ward warn her not to do it, but Elizabeth is determined.

And so there were two confrontations with him, some of them written. She writes down her concerns, which is partly how I know that they’ve happened, and I know exactly what she said to him. And McFarland responds to this plea for clemency for other women and this laying out of her own case saying, “What evidence do you have to keep me here? Surely you can see by now that my husband was the liar,” and she gives these documents to him and awaits his response. After church one evening, which is held in one of the halls in the asylum, Elizabeth is following the other women back to Seventh Ward when she feels a hand on her arm, and it’s McFarland. And he leads her away from the other women and they walk through the corridors to an unfamiliar door. And he opens it and says, “You must reside here instead.” And he sent her to Eighth Ward, which is one of the worst wards. It is punishment for her audacity to challenge him, and it’s intended to silence her once and for all.

AA: Tell us about the Eighth Ward.

KM: The Eighth Ward is horrific. The moment Elizabeth comes in, the stink is the first thing that hits her. This is a ward that is unclean. There are puddles of urine everywhere, there’s excrement smeared on the walls. The women are wild, unwashed creatures, screaming, hitting. It’s not a safe environment. These are women to whom no humanity has been shown, and so they themselves have lost their humanity. It’s a place where Elizabeth sleeps in a dormitory rather than a private room as she’d had on Seventh. They’re locked in at night, so she’s given a bucket to pee in, and she’s locked in with these wild women who she doesn’t know what’s going to happen. She frequently feared for her own personal safety. And she really feels that all hope is lost. She describes it as “the blackest night of my existence” because she has tried to speak up, she thought she had found in McFarland someone she could trust, someone who was going to be her way out of the asylum in this situation. And instead she has now been sent to this hellish place and she sees no way out, she’s completely trapped. Her fate is entirely in McFarland’s hands, and it turns out he’s a man just like her husband, who cannot be trusted, who has used that power over her to squash her and to try and break her.

And what is remarkable about Elizabeth Packard is how she responds to that situation. She was a woman who was filled with a spiritual and religious faith. And though she is devastated that night, she arises the next morning and thinks, as she puts it, “Events are God’s, duties ours.” And she decides to leave the big picture to God. He will figure out a way to get her out. Her responsibility is to deal with the here and now and to live those values that she believes in and to be the woman she knows that she is. She is not an insane woman who should lose her humanity. She is a woman of intelligence and kindness and she’s incredible.

The very next morning, she asked the attendants for help, and she decides she’s going to transform the ward. So she herself scrubs the walls until they’re clean. She herself befriends the women, her fellow patients, some of whom have not been touched in years with any kindness. And she washes them, cleans them, washes their hair until the whole ward is sparkling. It takes months to actually get through every woman on the ward, but she does it. And focusing on that gives her the strength to get through her suffering.

And something else rather special happens as well. She’s been sent now, as she put it, to be broken in and she’s supposed to become this obedient wife, but she says, “In my case, this woman-crushing machinery works the wrong way. The true woman shines brighter and brighter under the process instead of being strangled.” And she wrote something else in the asylum which I love, it’s one of my favorite quotes from her. She said, “The worst that my enemies can do, they have done. And I fear them no more. I am now free to be true and honest. No opposition can overcome me.” And it’s through this suffering, and it’s through helping others that she truly becomes the woman they could not silence. Nothing McFarland can throw at her can hurt, because she knows who she is. She knows she’s sane, she knows she’s right, and she has this faith that all will be well in the end, and she remains true to that conviction. And in so doing, she inspires the other patients as well to become strong, to become resilient.

AA: It really is incredible. And I’m remembering too, in these scenes, it’s not easy either. I think one of the first times she tries to reach out in kindness to another woman on the Eighth Ward, she gets attacked. Like physically very, very badly hurt. So it’s not like she tries to be kind and they’re like, “Oh, thank you, we love you too” and hug her back and everything’s better now. She encountered a lot of adversity there too.

KM: Yeah, completely. She was beaten black and blue, she nearly lost her sight at one point. Yeah, it’s astonishing. But she persevered with kindness and patience and was ultimately rewarded. She ultimately becomes a real figurehead within the asylum. She was someone to whom the patients would voice their worries. She would try and help if there was any way she could to improve their situation, to be that advocate. A really extraordinary woman.

AA: Yeah, she really was. So again, I don’t want to tell the whole story of the book, we want to leave some things for the end. But I’d love it if you could talk a little bit about her broader activism also. She really made a huge difference in the individual lives of the women in the asylum, but then she was a massive social force also. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

KM: Sure. Well ultimately, and no spoilers, but ultimately, this incredible woman who is doing such incredible work within the asylum and also within herself… This is what I really love about the story, is that it’s a journey that we can all witness of how she changes her life, changes herself, and goes on to change the world. She does ultimately manage to get out of the asylum after years of being a patient there. And just to share a little gem about once she gets out, she is incredible because she’s completely penniless. She’s homeless, she has no support, she has the stigma of having been a patient in an insane asylum for years. She’s a woman who is not supposed to be out in the public world, you know, how is a woman supposed to support herself if it’s frowned upon that a woman works? All of that sort of thing seems completely contradictory. How can she make this work?

And to give a sense of how forward thinking she was and what a charismatic person she was, she decides she’s going to publish some of these writings that she’s been working on that she’s so proud of, and gets knocked back by every publisher who won’t touch her. They think she’s completely mad and that no one will be interested in her story. And so Elizabeth thinks, “Well, I’ve got no money. What on earth can I do?” And Elizabeth Packard, in 1863, 1864, crowdfunds the publication of her memoir.

AA: I love it.

KM: She literally knocks on doors and speaks to people on trains. You know, traveling by train, she’ll strike up a conversation with the person in the carriage and she tells them her story and she says, “I want to publish a book, but I have no money. Is there any chance you could give me 50 cents towards this book? And in three months time, if I’ve managed to get enough money, I will send you a copy if you could just give me 50 cents today.” And in this way, she convinces thousands of people to invest in her. And so she gets that first print run out and the book becomes a bestseller, a runaway success. And she can then use that financial freedom to do what her heart is passionate about, which is to ensure, as she put it, “that another sister in America does not have to suffer as she suffered.”

She becomes this incredible political activist who campaigns state to state, coast to coast, trying to change the laws. Changing laws both to protect patients who are in asylums, to protect those under threat of being committed, and to campaign for women’s rights more generally. For women to have the right to keep their own earnings, for example, for women to have the custody of their children. And she was a successful and really, really astonishing woman who campaigned all the way up for the rest of her life towards these important social issues even though she was constantly denigrated, even though everyone was against her. She herself was so persuasive, so intelligent, so savvy and clever that she got things done.

AA: She’s really, really an incredible person with an incredible story. Having you mention the children and custody reminds me of a loose thread of her personal life, that she was removed from her children. She suffered terribly, as any parent can imagine, with how much she missed her children, that she knew her children were missing her when she was gone from them. So what ended up happening with her children and with her husband? Because when he put her in the asylum they were married, they weren’t divorced. So how did her family life resolve once she came back home?

KM: Well, I won’t tell the full story, but what I will say that I think highlights another element of Elizabeth’s character, of just how giving she was and how smart, is that she does eventually return home to her husband and her children. And her husband moves against her for various reasons and she ends up a prisoner again, but manages to get out. And everybody is saying “Divorce him, divorce him, divorce him! Get yourself out from his power.” As things stand, he could still send her to another hospital even though she’s managed to get out of the first one. At any moment her liberty was under threat, that she could be carted off to another hospital where perhaps she wouldn’t get out, like so many other women that she had already seen in the asylum. Perhaps she would stay there for the rest of her life.

even though she was constantly denigrated, even though everyone was against her. She herself was so persuasive, so intelligent, so savvy and clever that she got things done.

And yet Elizabeth does not divorce Theophilus. And the reason she doesn’t is because, essentially, it’s an effective campaigning tool to remain married to him. Because if she can say to the politicians who she is trying to convince to change the laws to protect all women, if she can say to them, “Look, I’m standing before you campaigning, you can see that what has happened to me is a complete travesty of justice. And yet, with the laws as they now stand, with me married to Theophilus as I am, essentially I have a loaded gun against my head and he could pull the trigger and it would be completely legal for him to do that. You have to change the laws because I’m not the only one this is happening to.” And it lent an immediacy to her campaign. And as I say, it had that level of threat that was there. So she did not divorce him because it was expedient politically to not divorce him. She wanted there to be that threat so that she could use it. And though Theophilus has his own plans, again, Elizabeth is so savvy that she manages not to fall into any of his traps and she is able to use it as an effective campaigning tool.

AA: Well, that was a wonderful summary of the story. And again, I’m glad you left some things out because there were some real surprises all throughout the story that were just really delightful to read. My last question to you is: What has changed since Elizabeth Packard’s time and what hasn’t? And in fact, you end the book with a really compelling and striking scene from very recent history, which illustrates some things that unfortunately are still just as relevant today.

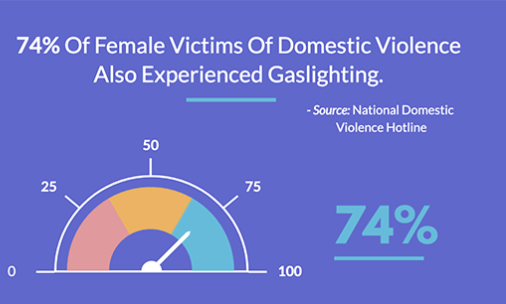

KM: What I found interesting about this story and this theme of the book when I started writing and researching is that it was still so relevant to the modern day. It’s still so prevalent that women are accused of being crazy. And it might not be carted off to a mental hospital, although I know from some readers that have contacted me that sometimes it still is that situation, but it will be a throwaway remark, a headline, a snarky comment, a tweet that is used to undermine women. So I think generally this is still something that is happening today. This allegation of craziness, of being hysterical, used to undermine women in positions of power, in positions that are in the public domain, but also in smaller domestic scenes. You know, gaslighting. “I’ve not been doing that. You’re the one who’s crazy.” And we see that play out again and again. So that is still very much going on.

I think it’s important that although legally huge gains have been made, we’re still not where we should be. People are always shocked when I talk about how this thing called coverture, the idea that a wife when she marries her husband loses all her civic identity, they’re shocked that that happened in 1860, but they’re even more shocked to know that it wasn’t until 1974 that a woman could get a credit card independently. Before then a man had to co-sign any credit application and the banks would discount a woman’s earnings by as much as 50%. That was 1974. This is easily within living memory and it just goes to show how there are these hangovers. We see things like with Roe v. Wade being reversed how a woman’s right to her own bodily autonomy is being infringed upon. So there are lots of things that are frankly depressing and that haven’t changed.

All I think we can do is to hope for more people like Elizabeth. Hers is an important story not only to recognize what she went through historically and to read as a great story, but I also hope it’s a book that people read and are inspired by in their own life. Whatever it is that they’re passionate about, I hope they can see how Elizabeth used her voice despite everything that was thrown at her and I hope they too will become women who could not be silenced. That they draw on her strength and resilience and put it into practice in their own lives to fight for whatever it is that they believe in to make the world a better place.

AA: Well, that’s beautiful and a perfect way to wrap up our conversation. So, Kate Moore, thank you so much again for being here. I so appreciated your book and this story that you’ve brought to light. So thank you so much for this conversation and for your work.

KM: Oh, it’s an absolute pleasure. Thank you so much for shining a light on Elizabeth and for all you’re doing to bring these stories to light. So, thank you.

The worst that my enemies can do, they have done.

And I fear them no more.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!