“I couldn’t be an outsider. I had to start to be part of the solution.“

Amy is joined by FIDE Grandmaster, Maurice Ashley, to discuss his incredible journey from not making his high school chess team to becoming the world’s first Black Grandmaster, plus how patriarchy manifests in the world of competitive chess, and valuable life-lessons we can all take from this remarkable game.

Our Guest

Maurice Ashley

Maurice Ashley is an American chess player, author, and commentator. In 1999, he earned the FIDE title of Grandmaster, making him the first Black person to do so. Ashley is well known as a commentator for high profile chess events. He also spent many years teaching chess and is the author of Chess for Success, Move by Move, and a children’s book, The Life-Changing Magic of Chess.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: How much do you know about chess? About the game itself, about the history of the game, the top players, the culture in the chess world, the race and gender dynamics in chess? I’ll admit that if it weren’t for my husband’s career in chess, I might not have ever discovered this incredible game and this fascinating world, nor would I have met some of the most inspiring people I’ve ever had the honor to meet. One of these people is Grandmaster Maurice Ashley, who recently came out with a book called Move by Move, and I’m so excited to talk today with Maurice Ashley.

Thanks for being here, Maurice.

Maurice Ashley: Amy, thanks so much for having me.

AA: I’m really excited for this conversation. I’ll first introduce you with a really brief professional biography, and then we’ll dig into your story more personally after that.

Maurice Ashley is an American chess player, author, and commentator. In 1999, he earned the FIDE title of Grandmaster, making him the first Black person to do so. Ashley is well known as a commentator for high profile chess events. He also spent many years teaching chess, and is the author of a children’s book, The Life-Changing Magic of Chess, and Chess for Success, another book, as well as Move by Move, which we’ll be discussing today.

So I know that’s just the tip of the iceberg of all of the incredible work you’ve done, but maybe you can kind of walk us through your career, but starting even earlier, Maurice, tell us where you’re from, kind of your background and what brought you into the chess world, and what brought you to do the work that you do today.

MA: Wow. Even those questions sound like another couple of hours just to start, but I’ll say I was born in the island of Jamaica and many people think of Jamaica as like a party place. But when you live there, especially when you live in challenging neighborhoods, then it’s not simply a party place. It was pretty difficult upbringing.

In fact, my mother came to the United States when I was a two-year-old. She left three of us—my brother, sister, and myself—with her mother, our grandmother, and came to the United States, spent 10 years working, saving, getting our citizenship so that she could sponsor us and brought us up 10 years later.

And it was while I was in Jamaica that I learned how to play chess because we played a lot of board games, but it wasn’t until I came to the United States—and two years in, when I was in high school—that I saw a friend playing chess and thought I’m good at board games. I’ll beat him. And he crushed me.

And I saw a book in a school library, in fact, on chess. And I didn’t realize there were chess books. Now I’ve got hundreds of chess books in my possession, but then I didn’t. I checked the book out, studied the book, went back to play my friend and…he crushed me again. And it turns out that he read that book and a bunch of other books. And that really started the competitive love affair with the game.

AA: Do you know that that’s very similar to my husband’s story? He played a couple of times when he was little, then not again, but then played with a friend and the friend just completely just crushed him.

Same story, Maurice. He went to a bookstore and was like, what? Like had no idea how deep it went and then started reading and practicing. And then he didn’t get obviously even near, like not even close to as good as you got, but it was that same process of… you think of it maybe as just another board game similar to other board games and you don’t realize it’s a universe of infinite possibilities and the intellectual challenge and excitement is what…

MA: He started the biggest chess company in the world, so there you go.

AA: Yeah, it’s like an ocean to you, right?

MA: Yeah, it is. It is an ocean indeed. It’s something that’s been going on for 1500 years in different forms before it finally crystallized about 500 years ago. But there’s so much that’s into it, that’s about it, that you learn not just the game itself, but so much about yourself when you play. And it’s that immersion, it’s that obsession, that passion to be really good and hopefully getting as far as your talent takes you that really hooked me in and made me want to play all the time. My mother thought I was crazy. Like who’s this obsessed child of mine who just wants to play chess every single day? And little did she realize this was going to be my life.

AA: So you started playing around high school, you said?

MA: 14 years old.

AA: 14 years old. Did your school have a chess club? Did you have a teacher?

MA: Yeah. My friend who beat me actually was part of the chess club and I couldn’t make the team. Kids were too good. Even when I graduated from high school, I still hadn’t made the team. It turns out that I got better than the rest of them, but at that time, no, I wasn’t good enough to make the top four on my team (which was Brooklyn Technical High School). So we’d play every day. My friend and I, his name is Clotaire Colas. He and a bunch of our other friends—few of our other friends, maybe like four of us, four to six would be the number—we would play after school. The two of us would be the constants; every single day we’d be playing after school. Then I would go home, do my homework and study chess. And that was rinse and repeat every single day for a solid two years.

Then senior year, I took a little bit of a break and then I kept back into it. I would play chess with them and I would also play in the parks. And that was really fun because New York City has a robust park scene. And so I’d go play chess in the parks with the hustlers who’d be playing you for money. I got to have 50 cents and they be like, yeah, well give us the 50 cents. But I wanted to play the best players and they were the best players. And you’d have this crazy scene. People think of chess as a quiet game. You’ve got to study and be studious. You have to hushed tones… not in Brooklyn. Get out of here. You’d see the trash talking, there’d be sirens blaring going by, you’d have music blasting. It was just absolutely what chess players would consider chaotic mayhem. Like, what is this? That’s the way I grew up learning how to play.

AA: So did it ever cross your mind that you could make a living doing chess? Or were you just like, I can’t not do it. Clearly I was born to do this. I can’t get enough, but like…oh shoot. Eventually I’m going to have to figure out what to do for a career.

MA: I was hooked. My brain couldn’t stop thinking about chess. Period. A living? I didn’t know what that meant. In fact, I didn’t make any money off of chess until I started coaching; a coaching job that was offered to me sometime around the junior year of college. I was studying to be an electrical engineer, but it was taking up so much of my time and mental space, trying to do all the differential equations, calculus, physics…No, that’s got to go. So, I switched my major to creative writing so that I could have more time and it’d be less intense, so I could study chess because that’s what I wanted. I wanted to become a Grandmaster.

Once I started reading in the magazines and books that there were such things as Grandmasters I went over their games. I was entranced by how good they were. I wanted to be that, and I had no clue that I would make money off of it. I knew that there were prizes in chess tournaments—by then I had started playing in chess tournaments, but to really make a living, like real numbers…not a clue.

It wasn’t until, like I said, in my junior year or so of college. I forget exactly what year it was because I also took the slow boat to graduating college on top of it because I was doing chess. I got caught in the whole chess fever and coaching. I got a job coaching chess in Harlem and that became my world for a while. And it paid—at the time it was $2400—so it paid $50 an hour and a job paying 50 bucks an hour. I mean, even now a job paying 50 bucks an hour… imagine it’s the late eighties and you’re getting 50 an hour. I was only able to work about eight to 10 hours, but still, as a college kid making that kind of money, paying the bills and stuff was like Wow, this is a pretty decent thing. My mother of course was tickled pink because she never made 50 bucks an hour in her job. So money started coming from chess that way, it would later develop into a real career.

AA: Okay, that makes sense. Because hearing it and—I know you’re a father too—and so half of me is like, Yes, pursue your dreams, do what you were born to do. And half of me is like, Oh no, you’re dropping out of electrical engineering to do what? It’s just, it’s scary. It’s a risk.

you learn not just the game itself, but so much about yourself when you play

MA: You sound like my mom. Exactly. And it was, it was a gamble. That was a real gamble. You know, I had it. That’s what it was. I just had it. I wasn’t your average person, even though I’d started super late, odds were against me.

Usually you should start when you’re six, seven, eight years old. That’s when people become Grandmasters. But I was hooked and I had a mind that allowed me to soak up the game at a rapid rate, that I can actually just read and learn and grow. Usually people are having lessons with trainers. I didn’t have a trainer until I was 21 years old. So that whole first period was just me studying, playing against my friends, playing in the parks, playing in tournaments when I could. And I just caught on and the game basically chose me, And when it said, I got you, it was not going to let me go.

AA: That’s amazing. So why is chess so good for the brain and why is it so good for the character? What are some aspects of chess that are enriching, ennobling, or however you would describe it?

MA: Well, the greatness of chess is that it’s really a discipline masking as a game. And it’s been around for all this time because the aspects of the game that make you good at chess really apply to real life. So we’re talking about critical thinking skills.

We’re talking about problem solving, focus, concentration, patience, winning and losing with grace; all these very wonderful character traits that you want for yourself and for your children are immediately applicable and learnable from chess. And so that’s what my whole book Move by Move is about. These kinds of characteristics that you develop and the kind of lessons that I learned over the years of playing chess. And it’s that serious. It’s not just some board game like my mother thought, but it’s actually something that is enriching, that is something you can learn from and apply in everyday life.

AA: Okay, so let’s dive into the book and maybe have you pull out and highlight some of those themes that you write about. There are so many different aspects so could you choose, like, three? A couple, maybe two or three that are kind of big standout things that we could learn from the book?

MA: Sure. Let’s start with the first one. I think it’s chapter one, and it’s huge for me. And it’s the idea of always maintaining a beginner’s mind.

I tell people, as a Grandmaster, I’m an advanced beginner and people are surprised by that. Like, what are you talking about? You’re a Grandmaster. What more is there to know about chess? But in fact, there are more possibilities in chess, more positions than atoms in the observable universe. That’s 10 to the 120th power. 10 percent of that is 10 to the 119th power. So all those possibilities… it’s impossible for us to know even a 10th, even a hundredth, you could keep going off the possibilities in chess. No human mind can maintain all of that. So one of the things that happens is you go from being a Beginner to an Intermediate Player (I’m even jumping over some rating categories) but an Intermediate Player, then you get pretty decent, pretty proficient. You may be an Advanced Amateur, then you become an Expert, then you become a Master, then you become an International Master, then you become a Grandmaster—the highest title that you could have—and when you arrive there you more than anyone understand that you’re still a beginner on a journey.

And you could actually look at it and say ‘That much I know, and there’s this much more that I don’t.’ And the ability to maintain a beginner’s mind is so important for growth because it’s when you think you know that you stop growing and it’s what you would call conscious incompetence. Like I know the areas that I’m not good and a lot of players can’t know what I know in this area, that I know there’s so many more things for me to learn about chess. What is even deeper is areas of unconscious incompetence. Even for those who are fairly competent in an activity, there are areas that I actually don’t know that I don’t know. I don’t know what’s there.

The engines, today’s computers, have shown us this incredible world of possibilities that we didn’t even imagine existed on the chessboard. Certain kinds of moves you could play, it’s like…you can do that? We never thought you could get away with moves like that. And the best computers now are like, yeah, absolutely. Push your H pawn, the side pawn (you’re supposed to be pushing center pawns). Push it down the board. Blowing our minds with their possibilities. So I think that one of the huge things that chess has taught me is even as a Grandmaster, I’m still an advanced beginner and I need to always maintain that humility and that openness to learn and that wonder with the game, even though I’ve been playing for over four decades.

AA: I love that. I’m just thinking of ways that I can apply that to my life and my work. I’m not a chess player, but just the humility of approaching things, not thinking that because I’ve read X number of books on this topic, that I know everything about it. Because once you think you know, then it blocks—like you’re saying, like you just pointed out with the H pawn—it blocks possibilities, right? And what if I have assumptions in my head based on what I’ve already learned that block me from seeing something that’s really critical that I’m missing.

MA: Everyone does. We all learn a certain way and there’s a very famous story of Mikhail Tal. I write about this in the book Mikhail Tal was a world champion, he was an absolute genius of the game, one of the greatest attackers of all time, and the story goes that he would go to beginners classes, sit in on beginners classes and be listening to the teacher teach. Now you can’t imagine the teacher is thinking ‘You’re Tal. What are you doing in my class? You could crush me.’ But Tal understood that the teacher breaking down chess a certain way may actually offer him interesting, intriguing insights that are different from the kind of calcified knowledge that he already had. And all he needs, a player like Tal, is one small insight, just a little bit of a different way to look at chess to suddenly make him a better player.

So he would even go into beginner’s classes, have the humility to be a world chess champion and be going in beginner’s classes in order to stimulate a different way of seeing the world, a different way of growing. And we should all do that. Whatever your assumption, you can go back to your baseline assumptions and realize that there’s a lot of truth there for you to uncover.

AA: I love that. That’s so great. Okay. Give us another one. What’s another highlight or takeaway from the book?

MA: One of the biggest ones for me is… I have two of them remaining as you mentioned. I mean I have more, but these are my favorites. One is the idea of always, always trying to see the world through another person’s point of view. Now, this is just about impossible. Truth, right? Because we’re sitting locked in our bodies, locked in our skulls. Our brains are seeing the world from the outside. You cannot see the world or even yourself the way another person sees it. The attempt is what matters and in chess, the reason I bring this up because in chess when I’m playing a chess game I cannot think that my ideas are so wonderful that I’m going to ignore my opponent’s ideas. That’s a recipe for absolute disaster. You have to very carefully understand every little bit of nuanced idea that your opponent is using to try to kill you. And even you might even understand it better than them. I remember seeing, I think it was Steinitz, maybe it was Petrosian. One of the great world champions, they said this person would see ideas before his opponent concocted the idea. So the opponent will be playing and all of a sudden realize, ‘Oh, I have a….Wait a minute, I thought I had a threat, but it’s already been stopped.’ So anticipating what the opponent was going to do was this great skill.

And we live in such a divided environment, particularly here in the United States. But it’s all around the world where there’s this division where it’s all about my opinion, right? I’m seeing it the world my way. And to truly try to deeply understand the other person’s point of view, whatever their background is, is not a skill we cultivate and to our detriment in so many areas. But in chess you have to, have to, have it. Now I’m not saying that all chess players think the way I just said. that you should be applying this in real life as well. A lot of chess players, I think to their detriment actually, don’t think about applying chess principles to their everyday life. But this one to me is a huge one because it speaks to the kind of harmony we could have, at least a better environment to be in if we just really focus very deeply in every situation we can on the other person’s point of view and understanding the other person’s point of view.

AA: Yeah, I agree. I strongly agree. And I have a love-hate relationship with social media and with the comments section. I mean, it can be such a cesspool and just drag you down and can sometimes not be great for mental health. But, you can really see kind of the tone and you can learn a lot from the conversations people are having. But one of the most disappointing and distressing things that I see in the comments—because I do all this work with gender and intersections with race, especially—but I just see people are increasingly unwilling to have empathy and just sit and listen to the other person. I even get criticized because I am so often trying to think, like, what’s the truth in the argument that’s being made here, or what is the feeling? What is this person’s lived experience? Where are they coming from? Because clearly their point of view makes sense to them, right? So how can I get in their heads?

And the way I see it is if I get inside their heads and I can empathize, I can still come away disagreeing with their point of view, but either way… like let’s say I do, let’s say I end up like, Okay, I still don’t really agree with your conclusions here, but I know why so much more deeply because I can understand it. Or, I find out I’m wrong, and that’s a win too because then, again, I’ve learned something, I’ve grown. So I just don’t see why people are…I guess it’s just human nature. People are scared to be wrong, or people kind of go tribal and want to see us versus them. But I’m committed to doing bridge building, Maurice, and it is not a popular position to be in right now.

MA: No, it’s not. And I’m not sure if it’s human nature or it’s cultural. And that’s another aspect of chess, by the way. Because the game is so complex that certainty is not promised, period. You think Grandmasters think 5, 10, 20 moves ahead. No, the game is too complicated. We try not to make a mistake on this move, right now. And we’re blunder checking. Am I making a mistake? And I’ll try to see how far I can go. But the main thing is to find the core, the essence of the position that it speaks to you about what to do next. And we cannot predict the future any more than, you know, you’re sitting in New York City and an earthquake happens. We just know that it’s unpredictable.

And so uncertainty is a part of the human condition and people don’t like it and so people want to be sure. They want to be certain, and it makes them feel better when they can know the other person doesn’t know what they’re talking about because ‘I do and whatever their position is I’m not interested.’

When is the last time you heard in a political debate one side say ‘Wow, that’s really deep actually, I’m going to rethink my position now because I think I was wrong.’ That never happens in a debate, ever! Think about that, two people, intelligent people, are arguing with each other, and no one ever comes away being wrong? That makes zero sense. That’s just ridiculous. And we see that happen so often and we take it for granted that they’re just going to debate each other and in the end they’re just going to part ways and not have reached agreement. How toxic a situation is that in society that even when one side may absolutely be wrong, it’s not going to be admitted and we’re just going to walk away divided as ever. That’s something that has to change. If we want to have a more healthy, wholesome, less toxic environment for our kids and grandkids to grow up in.

AA: I think it’s neat too. I mean, coming back to chess on this topic still, I’m just thinking about… because as you’re studying your opponent, I mean, you do want to win the game, right? You’re studying the opponent so that you can anticipate what they’re strategizing and so that you can counteract it. But at the end, what I always see in all sports that I respect is the meeting of great minds or great athletes and at the end, they shake hands and again, they’ve learned something. There’s respect between them. You’ll take what you learned in that game to your next game. And so that ability to learn from each other and spar with each other or have a meeting of minds that helps both people grow is kind of what I’m taking away from this too.

MA: Well, sports is its own defined universe, right? We love sports because they’re exciting. We love that there is a drama that is infused by the fact that one side is trying to win. The other side doesn’t want to lose. So it’s a fixed space. But sports does not define the world to say… well, chess doesn’t define the world. It’s its own universe, but that doesn’t mean you can get these worldly lessons, these life lessons from this activity.

And there are many people who come out of sports and say, ‘Win at all costs. It only matters if you win. Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.’ There are people who come out with that mindset. That’s why for me, the life lessons I write about in the book are personal, and I would hope that others share my viewpoint.

I know that’s not necessarily going to be the case. So there are different lessons you can learn from any activity. And again, competitive sports is its own universe, but there are definitely great lessons about learning from the other person that will allow you to grow.

AA: Okay, tell us another one of the lessons. What’s another one from the book?

MA: Another one for me is the idea that the journey gives value to the destination. Now, a lot of people will say it’s about process, not necessarily result, and I understand that but to me the point of any great goal, what gives great value, what makes it a fantastic endeavor is the fact that there’s this journey that you’re going to go on, this quest, and that this quest will take you to highs and lows. It will have twists and turns. It will challenge who you are as a person. It will test your resiliency, your determination, your ability to solve problems on the fly to stand in the face of failure and continue nevertheless. And actually the greatness of the destination, what makes it such an amazing quest, is all based on that journey. All of it.

So people like the quick solution. I want to be a millionaire. Or weight loss, like, I just want to lose the 20 pounds now. What do I need to do? But if I gave a fool a million dollars, they’re just a fool with a million dollars. Because if you take that million away, they don’t know how to replicate the path. They don’t have anything in their character even that would allow them to make that million back because they’ve never gone on the quest. And so a lot of times people have goals and don’t realize that the process is actually the goal. The process is the point of it all. Yes, you can have that goal, but it may happen that while you’re on this quest you’ll find that the goal doesn’t matter or that there’s a different goal you should have been pursuing. It’s still okay to be pursuing that goal as much as you can, but it may teach you something else. And that’s the new discovery that you want to find.

And so chess is move by move. It’s one step at a time. It’s not being impatient. It’s not trying to rush the result. You know, when people say, ‘Oh, you’re a Grandmaster, you could probably beat me in two or three moves.’ That’s not what I’m about. I’m about the long game. The fact is I’m going to beat you and it doesn’t have to happen quickly. It just has to happen. So to me, that’s a lesson for life. That’s a lesson for living; that it’s endless. And it’s really the journey that gives value to the destination.

to truly try to deeply understand the other person’s point of view, whatever their background is, is not a skill we cultivate and to our detriment

AA: Hmm. I love that. That’s so great.

Okay. I have some more questions for you. I’m wondering, so I want to talk more about the fact that you became the world’s first Black Grandmaster in 1999? And I wonder how that felt for you. If you can just kind of tell us what is the racial makeup in the world of chess? What was it then in the eighties and nineties when you were coming up in the world of chess? What factors create the demographics and then how did it feel for you?

MA: Back in the day, I saw no one in the chess world that looked like me and I wasn’t trying to become a Black Grandmaster. I’m already Black, I’ve succeeded at. I wanted to become a Grandmaster and that was it. But it was impossible to be in the space and not feel different, not be perceived as different in the environment.

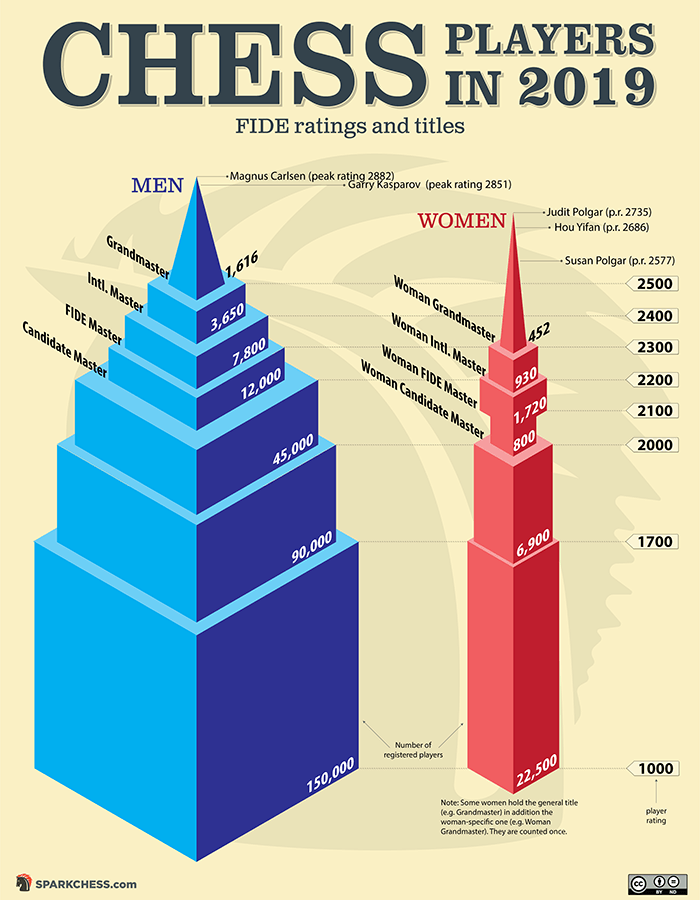

And also for Black chess players to realize that I might actually make it and start goading me on. Like, Come on, we’re supporting you. You’ve got to do it. You’ve got to do it for us. Note ‘for us’, not ‘for me.’ Of course they wanted me to be successful. There was this feeling like we were less than, like we couldn’t be good at an intellectual game like chess. And there was definitely that undercurrent in the accomplishment. So I did feel the pressure. I wanted to become a Grandmaster. That was hard enough, but I did feel the pressure from the outside about doing this thing that no Black person had ever done before. There are now still very few Black Grandmasters in the world, or about a couple of thousand Grandmasters. I hear varied numbers between 1700 and 2000. I think it’s closer to 2000 now, but there are very few, you can count them on one hand.

Now that said, it’s an interesting division yet again, because there are some players in Cuba and when you look at them, it’s like, ‘you’re Black.’ But we would categorize them as Latino. And there was one player, Román Hernández, who was very fair-skinned and if you glanced at him, you would think, ‘Okay, he’s probably mixed or Latino or what is he?’ But in Cuba, they would call him Black. And if you were to say, who’s the first Black Grandmaster in Cuba, they would say he was before anyone else. But we would look in this country and in a lot of other places, I imagine, and look at him and go, ‘Well, I’m not really sure.’ And I found this out much later. I found this out a couple of years ago because he passed away and…he was good way back. He was good in the seventies before I came up.

So when I look at that I think, what is it really? What are these divisions? Who agrees on what, who makes the rules, et cetera… And so it’s still a complex space for me. It matters and it doesn’t matter at the same time.

AA: Thank you. So I have a couple follow up questions. You had a childhood in Jamaica, right? And then moved to Brooklyn, New York. Were you in a majority Black neighborhood in high school?

MA: Yeah. I was in Brooklyn. I grew up in the same neighborhood as Mike Tyson. And I always joke: Brownsville was so rough that Mike had to get out of Brownsville. So yeah, it was the hood for sure.

AA: So basically what I’m asking is—going from your family, your school, your neighborhood environment, but then entering the chess world, which was majority white—was that weird for you? Did you find that you had to code switch in certain ways or did you get used to it eventually? What was that like to make that jump, that transition between worlds?

MA: Well, I think my first step was Brooklyn Tech High School because in Brooklyn Tech there were kids from all over the city with backgrounds from all over the world. So that was pretty cool to go to a high school… it was a specialized school, you had to test to go in. But in that school, you had everybody from everywhere. One of my best friends, Stan Roosevelt was Jewish from the then Soviet Union, and he lived in a neighborhood next to mine. I’d go over to his house and play chess and that was interesting, walking into a completely different type of neighborhood that he lived in.

That’s one of the beauties of New York City; you’re around everybody. You may not see them in your neighborhood, but once you step outside your neighborhood—on subway trains, in the city—you see everyone and they’re from all over the planet. So I think that diverse background and the diverse ethnic groups and races really was fantastic in New York and it made it much easier for me to acclimate once I got to chess clubs where there were not many people who look like me.

AA:. That makes sense. It’s just so amazing and so inspiring when you do see the first person to break a barrier like you did. Or in athletics, again, the first person to break the four minute mile and nobody thinks it can be done and then so many people follow after because what you can conceive you can achieve, and it’s just really hard when you haven’t seen it be done. So following up on your comment that you felt some pressure to represent an entire group of people to like do it for us…which is crazy and it’s unfair to have that pressure be on the point of the spear, but that’s just how it is. So my question is whether there was structural racism in the chess world or bias, like racist comments, or was it just the absence of the role models that created the barriers for you, or maybe a combination of those factors?

MA: So I grew up in the eighties playing chess and, you know, when I think about the people before me, the Jackie Robinsons of the world, the Arthur Ashes, the Wilma Rudolphs, you name it, there’s a long list of people who had stuff to overcome that I simply didn’t. They had already fought the battles to a certain point and Dr. King and the entire civil rights movement and many, many others. That by the eighties, yes, there were still issues, but segregation in New York wasn’t a thing, for example, you could go anywhere and be in any pool or hotel and that wasn’t a problem. So I was well aware of history and they inspired me, the struggles that those folks had and the autobiographies I’d read, the stories that were either told to me or I would consume myself. I just understood that I’m standing on the shoulders of giants and it’s my responsibility to forge ahead regardless of what’s in front of me.

In terms of structural racism in the chess world, I wouldn’t say it existed structurally, but there certainly were people who make comments, said absolutely ignorant and even racist things. And that’s also part of being a Black person, especially in a majority white culture. In Jamaica, I didn’t hear any of that so that wasn’t something I grew up with. I learned about it pretty quickly though in the United States, unfortunately. And there would just be ignorant comments and racist comments, whether it’s ‘You let a Black person beat you’ when I beat a player, which was stupid. And it got worse. I mean, it definitely was more intense than that.

Again, for me, not only was I playing against these players and beating them, but I also had friends who I was able to play with and who were pretty good players. They may not have become Grandmasters, but they were pretty good players, experts, master level players, and they were warriors. And when they saw somebody in front of them, they didn’t care if you were green, purple, whatever color—we didn’t care where you were from, all we knew is we just want to crush you and that’s it. And so that fighting spirit is something that definitely pushed me forward and allowed me to essentially deflect any of the ignorant comments that came.

AA: That’s really great to hear. I mean, I’m so sad and about hearing those awful cutting comments that you had to endure, but it’s really inspiring to hear too, and I’m glad you did have friends that were in there with you that you felt like you weren’t just all alone…

MA: I mean, you know Black people stick together. I’m going to put it straight, it’s like don’t mess around. You know, you might be the mild one, but you’ve got your Malcolm X right behind you.

But yeah, I had friends. There was one group that I have to mention, the Black Bear School of Chess. They were a group of Brooklyn chess players who were largely African American. It did include one Latino, Herminio Baez, he’s passed on. But they were warriors. And let me tell you, I had a chance to play against these guys. I met them in Brooklyn and they were part of my trial by fire where I would go to one of their homes, Willie Johnson, who everyone calls Pop, we’d go to Pop’s place and there’d be 10 players, bunch of chess boards, and everybody was playing blitz and trash talking. Music was blaring (Pop liked to have jazz on as opposed to hip hop). It would just be this great environment where I played. And I mean, the names of these players, William Morrison, who they call The Exterminator, he rose to just about international master level, Ronald Simpson, The Fire Breather. Ronnie has passed on; he was one of my dearest friends. He was such a warrior. I mean, they all were. If I started naming… Chris Welcome, Steve Colding, George Golden, Leon Monroe, Nathaniel Jackson.

There were so many good chess players that I could fight with. And you have to learn all these styles, right? Because they all came with a different outlook on the game and, but they were all about crushing each other. And that’s growing up in that environment that really prepared me for the rough and tumble world of professional chess.

AA: That’s amazing. That’s so cool. I’m so glad you thought to mention that.

MA: Yeah. The Black Bear School; the name comes from this idea one of them concocted that if you see a black bear in a forest, you have to kill it because otherwise it’s going to keep on coming. That was the mindset. You better finish me off. Fight to the bitter end.

AA: Oh, I love that. Okay, so we’re going to switch gears. I mean, the podcast is called Breaking Down Patriarchy and you and I met Maurice because you were grappling with a gender disparity in the chess world. That’s kind of what led us to meet each other initially. So I’m wondering if we can talk about that for a minute and have you talk about the gender makeup of top level chess. I don’t know if you know the exact percentage, but what that looks like. And then let’s talk about the gender gap. There’s a big, big gender gap in chess and there are various hypotheses about why that is. So if we can explore that for a minute, that’d be great.

MA: 2%. That’s the number. It is 2%. 2%. There are 40…I think it’s 41 now, women who are Grandmasters, who have the official Grandmaster title in chess, and there are about 2000 players who are Grandmasters. So you can check the numbers and check my math. It’s something that’s pretty stark and frankly, just unacceptable. And there are so many reasons we could talk about. And it’s hard for me to pin down this is why this is, you know, this is exactly what’s going on.

There are people who just say women are not as good as men in such a field. Done. Argument over… not so fast. There is also the fact that when you’re in an environment where one side dominates in the first place, how do you really feel comfortable in that environment? How many people end up being in this environment that they feel like it’s something they want, to always be breaking down barriers?

There’s the fact that there is sexism in chess. The fact that if you’re a girl in chess. With all those boys, they’re going to hit on you. Boys are going to be boys as they say. So that’s another factor as well.

Another factor is parents seeing their girls playing chess as a societal factor. A girl at a chess club where there may be 20 grown men. Let me bring my little daughter into that environment and maybe insist that she stay, even when she might be a little bit uncomfortable and wondering why am I here and not hanging out with my peer group.

So they’re just all these reasons. I don’t know which percentage is what for what and all that and how it combines. It definitely is an issue and it has to be addressed for me as a chess player. It has to be.

AA: I have to say the first thing that you said too, where there are still arguments are made that are just like, women aren’t as good, biologically women are not as good at spatial understanding or calculations, or they’re not as aggressive, they’re not as assertive by nature. I feel like any time a girl hears that argument, that itself then becomes a barrier that is really hard to combat because then it lives in her mind, right? Then if she has all of these voices, anytime she hears that or reads an article about it that are like, wait, maybe I made that mistake because I’m a girl. Not just because I made a mistake. You know what I mean? And like, anyone would have made it. But oh yeah, because maybe I’m not as good.

In fact, I just interviewed an Afghan woman who said she grew up in Afghanistan, where everyone said girls couldn’t go to school. And when she started teaching herself to read and would be studying for hours and hours and hours when she would get a headache from the strain, she didn’t know whether that was because anybody would get a headache from the strain or whether it was because she was a girl and girls brains weren’t meant to study and read. So it seems similar to me, were once those voices get in there you’re like, Oh shoot. Maybe I’m really not as good and that becomes its own barrier.

MA: Absolutely. These are almost self-fulfilling prophecy. You give those kinds of messages, which are either sometimes subtle but even more overt, then people do digest them and then not be able to just simply pop them out of their mind. So, yeah, I think this is very real, a real phenomenon that occurs. But again, it’s hard to know where all of the soup of the balance is cause it’s so many things. As we know, it’s not manifested in only one thing in society. We could just attack one problem. We just solved this one right over here. It’s getting these negative messages out of society. Done… It’s not that simple because you also have the behavioral issues that come along with it, the other side sometimes even intentionally trying to keep the playing field unfair. There’s a combination of many things, and I think it’s really beholden on us to attack it on a multi-tiered front.

So in any uneven situation where one side has already taken a tremendous lead, it seems that to some people, you just have to tell the people who are behind that if they just work hard and push, try, make their best effort, that they’re going to catch up eventually. And that may be true, but it’s not going to happen that easily. The structure that gave this group a giant lead is still in place, or even if it’s not in place, the lead is still there, and that lead compounds itself over time, and that’s an enormous challenge for anyone who’s behind to overcome eventually.

And that happens in so many spaces. It even happens with chess rating. The best players make it harder for players behind them to catch up to them. You’ll see a sort of consistency at the top until they age out. They have to start having a deficiency in order, give up their lead because if I’m a good player and I’m playing a weaker player, that weaker player just keeps losing to all the better players, and they even take their rating points. So it’s something to be aware of and not just to make the cavalier statement that, ‘Oh, we see it happen in so many spaces where somebody just has to work hard, and then they’re going to catch up to another person because they did all this hard work.’ Man, they’ve got to do super hard work. They’re almost like superheroes in order to overcome what may be maybe a structural lead or a lead that resulted from a structure that may no longer exist.

AA: But it’s historical. And so it’s still in our habits and it’s in our culture.

MA: And I think in so many ways it’s in our social environment and even values and you don’t realize it because it’s somewhat invisible even to a person who was saying, ‘Oh no, I’m not, I’m not sexist in any way.’

You don’t know what you don’t know and you’re unconscious to some of your own personal biases. And it happens for all of us, myself included. Every one of us. We come with this baggage that we learned, A, as a child and B, from our homes, but also from society itself.

AA: Well another question I had was, I think our very first conversation, Maurice, because you travel a ton globally promoting chess, teaching, helping people, you know, achieve their potential in chess which is so inspiring and awesome. And you were talking about like different countries that you were visiting and observing cultural practices, some that are more encouraging to women and some that are less encouraging to women. Can you talk about that, maybe with the goal of this conversation being like…

Well, I guess what just came to me too is that that’s proof that it’s not really innate, right? Because if you have certain places and we’re all human and you have certain places where women are not achieving and then places where they’re achieving more that means it’s more cultural. But anyway, can you talk about some of those factors in different places that are more encouraging or discouraging to women in chess?

MA: Sure. I know if you look at the Republic of Georgia, for example, in the former Soviet Union, their women are incredible chess players and they are supported by the government and by society to become good at chess. And you look at China. You look at India, these are places where more women are being pushed into chess, supported with chess. India just had its first ever female Grandmaster. In China, the women are actually the best women in the world, the world champions are now consistently coming out of China. Current world champion Ju Wenjun is also from China and she’s a Grandmaster. So you see these spaces where women are truly pushed and folks believe that they can achieve even the highest title.

Then you go to some places…and there are a lot of places where it’s just, they don’t have the same buy in. And I have to say the United States is particularly bad. In the US there’s only one woman who’s ever achieved the Grandmaster title. If you look at African American women, there are over a hundred African American males who have crossed the master divide (master is a couple of levels down from Grandmaster). There are over a hundred. No woman has ever, ever crossed that level. And you’re looking at an open society like the United States where we claim to have more parity and maybe sexism is on the wane. But yet, you know, in a field like this we still have not broken through. One person has, I’ve broken through the glass ceiling, but not enough.

I remember I was at a tournament in… I was in Baku, Azerbaijan and it was the Olympiad. The Olympiad is where a gathering of many countries, over 180 now, come bring their best teams to play chess against each other and the best team wins the trophy. After about five or six rounds, all the wealthy countries had teams on or near the top and all the poorer countries had teams that were way down at the bottom and you’re like, it’s a game like chess, why should wealth matter so much? And it did. It was very clear just looking. The difference was anyone who could invest in training and travel to go to tournaments and chess just remains a wealthy person’s game.

Even when you looked at inside countries, I would look at many of the African nations and the women on those teams played so poorly. And it was annoying me. They were all on the bottom boards and I had friends I knew and when I spoke to, for example, the Kenyan team, and I was going over their games one evening and I said, ‘Why do you play this basic opening? This is for what beginners normally play.’ And they said to me, ‘This is what we were taught.’ So instead of teaching them more complex openings, seeing things that were more dynamic and would allow for you to grow as a result of the fact that complexity forces you to adapt. Yeah. They were taught all the basic stuff, like play this, just keep playing this stuff. And that’s what they did.

So even within their own countries, women were being treated a certain way and not being offered the kind of education that would allow them to flourish. And so that just bothered me a lot and I’m now, I can’t say the word is…mission may not be the best word for it, but I’m definitely focused on seeking out and helping African American and Black women to become better chess players and maybe finally an African American girl break through this master barrier. Which there are some who are really close. They haven’t gotten there quite yet. But I think it’s something important. It’s not something I paid attention to. Most of my chess career, looking at it now, I feel like that’s something that has to be done.

AA: That’s so wonderful, Maurice. And I have to say how much it means. I mean, because I have also just imbibed so much patriarchy throughout my life. And I’m doing the work of breaking it down to dismantle it, but also understanding it in religion and government. But so much of the work is in relationships. It’s in our own mind. And to hear someone that I respect and look up to and especially, honestly, to have men doing this work is so important because for a man to look at a woman and say, ‘I believe in you. You are as good as anyone. You can do this. You were born to do this.’ It helps. It really helps to counteract all the patriarchy that’s been constructed in the mind. To have someone in a position like you’re in to say like, that’s garbage. Don’t believe it. Don’t believe it. Keep going. It’s just incredibly powerful for you to use that position you’re in and that platform that you have to do that work. I’m just so inspired.

MA: I appreciate that, but you know, I have a daughter and there is no way she would think any less of herself than pure greatness. I come from a competitive family. My sister is a six-time world champion boxer. Another came to this country and sacrificed all those years. My grandmother, who sacrificed later years of her life to raise us as kids. I have yet another sister who is a professional in her field and has raised three wonderful boys and, maybe the most competitive, or at least the biggest trash talker of all of us. I have so many friends, like I have amazingly, wonderfully accomplished woman who surround me in my life and maybe I was just born at a later stage so that we could digest some of the more positive messages. But to me, it seems basic.

Although I have to say, like I said, I didn’t do anything about it. In some ways I just felt like I don’t believe it. Right? And I support the women around me. So what did I have to do in a bigger way? But yeah, that event in Baku in 2016 and 2017, that event really opened up my eyes and made me realize that I couldn’t be an outsider. I had to start to be part of the solution.

AA: That’s so awesome. I will say too, I’ll use myself as an example again, cause I just talked about how, Oh, I have all these patriarchal messages. I’m also a really strong woman. And I mean, I hope that that’s true that the women in your life haven’t absorbed that messaging and they’re like totally over it. And I know there’s such a variety, but I will say I think people are surprised to hear me say that. That I do have that self-doubt that comes from so many messages of being told that I’m less than or that it’s not my place to lead or that it’s not my place to do this or that.

I do really hard work also to deconstruct it myself, so it’s not like I’m waiting around for a man to do it for me. And I am a very, very strong woman, but I’m just saying for a lot of people, it’s complex in there, right? There’s like all kinds of messages and some that are very empowering and we can push forward, but that there’s still like that little self-doubt based on something our dads told us or something that all these male role models and female… it’s sometimes what women say to us too, that it’s not our place to lead.

MA: I’ve had a number of female chess players, bigger number than you would want to accept say, ‘Yeah, men are just X than women,’ whether it’s more competitive, whether it’s physically stronger, therefore mentally stronger. I’ve heard that they’re just better chess players and that’s it. And I look at these women and these are accomplished women. I’m not going to name any names, but these are accomplished women in chess and you’re still open mouth like, Well, why did you get to where you are? And you’re saying this about the entire gender.

I’m very much shocked by it, and I will say, it’s a tricky position being a man who is an ally in the space because people wonder about your intentions. It’s the same thing that happens if a white person is an ally of a Black person and really pushes in a way that people say, ‘Well, why are you pushing so hard? What’s it to you?’ And those people have to overcome even that message that aligning yourself with this opposite group, which really doesn’t seem to have anything to do with you necessarily is a cause for suspicion in some sort of way.

And I know a lot of men who will stay quiet, they’ll just stay quiet on the issue. They don’t feel like they’re sexist. They don’t feel like they’re necessarily against women in any way or have this kind of negative thoughts, but they’re just not going to do anything. It just let the women fight it out or let it not be them.

We’re going to stand on the front line and trying to help break down what has clearly been centuries, if not millennia, of this sort of oppression.

women were being treated a certain way and not being offered the kind of education that would allow them to flourish

AA: Well, I have nothing but gratitude and huge high fives and kudos to you for stepping in and being willing to be such an ally and such a role model for so many people in all different ways. And I have to say quickly how grateful I am that you pointed out the wealth gap too, and the class difference, and how that impacts people’s ability to thrive and self-actualize in chess and across the board in the ways that they want to, because that’s something that’s so important that we don’t talk about enough as well.

Okay, well that brings us to the end of the episode. This has been such an amazing conversation and such a delight to talk to you. I’m wondering if we can sneak in one more question and have you talk about your children’s book?

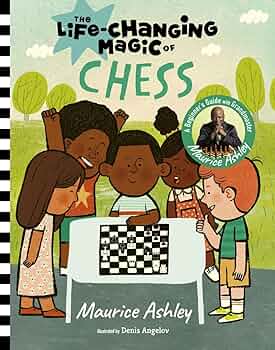

MA: Sure, The Life-Changing Magic of Chess. It’s a funny thing that this book was proposed to me. I didn’t think about writing a children’s book, but thankfully the company, Magic Cat, they were doing a series called The Life-Changing Magic Of series and it includes baking, it includes drumming, it includes skateboarding. They found people representing those fields. And they wanted to do chess and they chose me.

And so when they told me the idea, I said, ‘Of course, chess is magic. I definitely want to do it.’ And the great thing about the book is it’s a kid’s book for five to 10 year olds, early readers. I didn’t do any of the illustrations. I’m not that talented. Denis Angelov did an amazing job. And it also talks about the lessons I’ve learned from chess, but in a way that kids can understand. It tells a story of me learning chess in Jamaica, coming to Brooklyn, losing to my friend in high school, and eventually becoming a Grandmaster after a lot of effort playing chess in the parks as well. So it’s a fun book, 40 pages, easy to digest. And I’m really proud of it.

Alongside all the thought and effort that went into Move by Move (what we’ll call an adult book) there was also a lot of effort that went into… maybe not the writing as much, cause it’s only 2000 words, but making sure the chess positions were appropriate or the images were quite right and all that because Denis didn’t know anything about chess but I had to give him everything. You know how chess players are: you see a wrong chess position, they’ll point it out. Why is the king on the wrong square? Oh, why’d the board turn 90 degrees? So I had to have an eagle eye every page every illustration, etc… But it’s a gorgeous book and I’m super proud of it.

AA: I am so grateful that you pointed it out. I can see it on your bookshelf. It’s right behind you, I think. And I’m seeing it’s a very diverse group of kids too, right? Kids of Color and girls in that group. And that’s powerful, right? To have that be in your school library. Suddenly you see representation right in front of you like we were talking about. I’m so happy you put that out in the world. So anyone, listeners who are interested in chess or even just interested in life lessons from a unique perspective, I highly recommend both books. The titles again are Move by Move and the kid’s book is The Life-Changing Magic of Chess. And again, Grandmaster Maurice Ashley, this has been a total honor and delight. Thanks so much for being here.

MA: Oh, it’s such a pleasure, Amy. Thanks so much for having me.

When is the last time you heard in a political debate one side say

‘Wow, that’s really deep actually, I’m going to rethink my position…’

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!