“With bound feet they were able to create a foothold for themselves in the patriarchal society.”

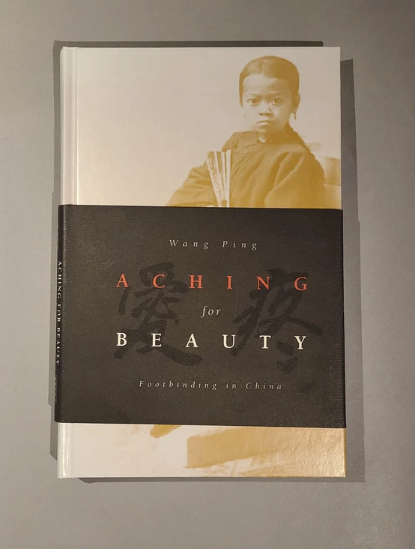

Amy is joined by author Wang Ping to discuss her book Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China and explore the nuances of beauty practices in China and beyond.

Our Guest

Dr. Wang Ping

Wang Ping is a poet, writer, photographer, performance and multimedia artist. Her publications have been translated into multiple languages and include poetry, short stories, novels, cultural studies, and children’s stories. Her multimedia exhibitions address global themes of industrialization, the environment, interdependency, and the people. She is the recipient of numerous awards, a professor of English, and founder of the Kinship of Rivers project.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: When I was a little girl, one of my favorite stories was Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid. Written in 1837, the original story is much darker and much sadder than the Disney movie. And one passage that I remember vividly is the Little Mermaid and her sisters having to clamp oyster shells on their tails. These oyster shells were terribly painful, but they were a status symbol, and it was their own grandmother who made them do it. I remember puzzling over that as a kid. Why would a grandma make her granddaughters do something really painful to their bodies, and something that had caused pain to her too?

It was with this passage of The Little Mermaid in my mind that I picked up the book Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China by Wang Ping. So you can imagine my surprise when the first chapter opened with a passage from The Little Mermaid! This was a different excerpt in which the witch tells the Little Mermaid, “Your tail will part and shrink into what humans call nice legs, but it will hurt just as if a sharp sword were passing through you. Every step you take will be like treading on a knife sharp enough to cause your blood to flow.” The book continues that “when the Little Mermaid finally stands face-to-face with her beloved prince her new feet, which she has traded with her lovely voice, bleed. The Prince does not notice it and she does not complain.”

The next quotation in this book at the beginning of chapter one is a Chinese saying that says: “A pair of tiny feet, two jugs of tears.” And the rest of the book brings to light the fascinating history of footbinding in China. And I am so excited to welcome to the podcast the author of the book, Dr. Wang Ping. Welcome Dr. Wang!

Dr. Wang Ping: Thank you Amy, I’m delighted and honored to be here. I’ve listened to quite a few of your brilliant podcasts and so I’m very honored to be part of this program.

AA: Oh, I’m very honored that you’ve listened to some other episodes and super honored. We were just talking about the amount of research that went into this book. It was an incredible book, I learned so much. And it’s one of the rare very academic books that was also readable. So, thank you!

WP: Haha, you mentioned that. Thank you! It was so funny because when I chose this subject, my PhD was in comparative literature and I actually couldn’t find a professor to advise me on this subject. And I actually did a minor in performance art. And there I found a brilliant scholar and he took me in. And the first thing I told the professor, a few professors actually, was that I wanted to publish this project even though I had just started doing the research for my PhD thesis. So therefore I wanted to write it towards more popular readers, not like those academic jargons, which often, to be honest, put me asleep as I was reading those books.

AA: Me too.

WP: And I hate reading. I had to pinch myself, pull my hair to get through it. And I really don’t want to write another book wasting so many of my years, because I knew it would take me quite a few years to complete this project. And I want more people to know about this history. And also to… how should I put it, because as soon as the Westerners think about footbinding, the first thing that comes to their mind is, oh, that’s horrible. Oh, that’s oppression. Oh, that puts women into slavery. And I went into this research actually with that prejudice. But as I was doing more research, more reading and talking to people with footbinding, also the memory of my conversations with my grandma who also had bound feet, I realized it is a very different story. With bound feet they were able to create a foothold for themselves in the patriarchal society.

AA: Well, I’m so glad you opened with that because that just immediately reminds us that the narrative is always more complicated than it appears on the surface. And certainly more complicated than it appears to an outsider looking at a culture that we don’t know anything about. And so I’m really glad you opened with that. I want to continue in that line of thinking with some questions I have for you, but first I actually want to back up and have you introduce yourself a little bit more with your professional biography and then also a little bit about your personal life. And maybe I’ll just read your professional bio quickly and then you can talk more about your personal background.

Dr. Wang Ping is a poet, writer, photographer, performance and multimedia artist. Her publications have been translated into multiple languages and include poetry, short stories, novels, cultural studies, and children’s stories. Her multimedia exhibitions address global themes of industrialization, the environment, and interdependency. She is the recipient of numerous awards, a professor of English and founder of the Kinship of Rivers Project. And also I think it’s so amazing you’re doing projects with The Moth and with Snap Judgment right now on NPR, right?

WP: Yes.

AA: That’s exciting, those are two of my favorite shows.

WP: Oh, thank you.

AA: So I wonder if you can back up and tell us a little bit about you personally. Where are you from and your family of origin, your passions and education and what led you to do the work that you do now?

WP: Well, I grew up in China. I was born in Shanghai. The Cultural Revolution began when I had just finished second grade, and so the schools were all closed. Books were banned.

AA: Sorry, will you back up because some listeners might not even know what the Cultural Revolution is.

WP: Oh, the Cultural Revolution is one of the political movements which lasted for 10 years. And it was very political and very tumultuous, to put it mildly. And for me, I was a child and I was just set, determined to go to college. Influenced by The Little Mermaid story, actually.

AA: Really?

WP: Yeah. Because I heard the story on the radio when I was like five or six years old and I just cried. At the same time, I really, really wanted to learn how to read and write and someday I’d like to, you know, I was living on the island on the East China Sea. And so I wanted to leave the island like the Little Mermaid leaving the sea and to see the world through books, through college. But at the end of the second grade, the Cultural Revolution began, and so everything was shut down. There were no books. And all the books were burned and banned. So I started sneaking into sealed libraries to read and I started exchanging books underground and eventually I formed my own underground book club. And basically I taught myself until I got into Beijing University.

AA: You were self-taught all the way through your education until college?

WP: Basically, yeah. Well, of course I couldn’t teach myself science even though my dream was to become Madame Curie, haha.

AA: Wow.

WP: I really wanted to be an astronomist, too, to explore space. So I knew, you know, I was considered very ugly and with big feet. And so I actually tried, everyone was mocking me, “big feet, big feet.” So I was very ashamed. And so I tried to bind my feet on my own without knowing anything about footbinding. So that actually later when I was in New York studying performance art, I was a professor. And also at that time I saw a pair of those lotus shoes, they’re so exquisite, so tiny, so inhuman at the same time. Yet so beautiful. And I just thought, how could any human put those feet into those shoes? It’s impossible yet it was real. So that brought back the memory of me being a six-year-old child just wanting small feet and started binding, enduring excruciating pain for a year to stop my feet from growing. And it did stunt my feet, actually. My feet are size 6½ but wide. They have to grow somewhere, right?

AA: What did you use to bind them? I think you said rubber band?

WP: Just cloth.

AA: Oh, just cloth.

WP: Yeah. I did not know anything about foot binding. I never saw any pictures except for my grandma’s feet. And she had bound feet that she let loose, but once you’ve bound your feet the bones are all broken. So you can’t really regrow the bones, you know? So she still walks really funny. She still has to stuff her shoes with cotton to fill in the space, and of course she made her own shoes to fit her feet. But I just remember the odor when she washed her feet at night. I grew up with no water in the house, no electricity, so we had to fetch water from outside and bring it in and boil water and have it simmer. So at night we each had half a basin of hot water to wash our face, then our midsection, then our feet. We call it the three. So I have the habit of, you know, cleaning myself in the three parts. And I remember the odor when my grandma washed her feet. And we all slept in one room.

…all the books were burned and banned. So I started sneaking into sealed libraries…

So in New York, I just thought, this is just really fascinating, me never knowing anything about food binding, but wanting to bind my feet for beauty to be accepted by my family and my neighbors, by the society. Because my mother had small feet even though she was tall. She is tall and my sister is taller than me and she also has small feet. And I’m the shortest, but yet I had the biggest feet, and that’s a no-no. So I started digging in New York at NYU and so that’s how it all began.

Meanwhile, coming back to myself, I came to the United States. I graduated from Beijing University, then I taught for a year in China. Then I came to New York to study English literature, and I walked into a wrong classroom at Long Island University which turned out to be a creative writing class. And Professor Lewis Warsh, who has passed away, he looked kind of crazy, but I think I’m kind of crazy because I like interesting people. And I like interesting things. And it turned out he is a poet and it’s a creative writing class. And I was supposed to take 18th century British novel. So out of curiosity, I sat down and wrote my first story. And the professor wrote, “You have a story to tell. You should start writing a novel.” And that is like, bang in my head. I just thought, oh yeah, that’s why I came to the United States to tell my story. So I started writing poems, and oh no, actually I haven’t, so I stayed in that workshop. That’s the only creative writing class I ever did in my entire life. And then the professor introduced me to Allen Ginsburg.

AA: In person?

WP: Yeah, of course. Yes. He was looking for a translator because he was organizing the first Chinese American poetry festival. So I said sure, I’ll do it right. So I worked with Allen for almost a year and we traveled together with the best Chinese poets and the best American poets, including Gary Snyder, John Ashbery.

AA: Oh my gosh!

WP: I know, I was lucky.

AA: I was an English major so I am so starstruck right now. Listeners, you can’t see me but my mouth is on the floor. I’m like falling on the ground. This is incredible!

WP: Yeah. During the translation period preparing for the festival, you know, translating actually is the deepest reading and writing you can ever do. And so that gave me the key into the poetry world. And I learned so much from the English language and poetics and I started writing poetry myself. And then I started writing poetry, then I started publishing. And the funny thing is that Lewis helped me get NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) and I barely got qualified. I just had my twelfth poem published, which was the minimum requirement at that time. And he filled out the form for me as a kind of joke, right? Because it’s NEA, come on, right? Like every big shot poet was applying every year. And Lewis, he is a very well known poet and published many books and has his own publishing company. And he never got it, but he said we still have to do it every year, so he just signed it and put my twelve published poems together. Then he asked me to sign it, and I had no idea what I was signing for. So then he mailed it as a kind of surprise and a joke, you know? And I won it.

AA: Oh my goodness.

WP: And I believe that year, who’s the poet who won the Nobel Prize? Glück?

AA: Oh, Louise Glück!

WP: Yes. She was on that. Also that year, she picked my poem for the best American poetry. So it was like suddenly you walked into the wrong classroom, the wrong river, and then suddenly everything just boom, just happened. I came to America, that was the dream that I wanted to get a PhD. And of course the only way for me to do it, you know, I never studied math. Even though actually at that time, just everything was happening. I was engaged to a professor at McGill University, I already moved everything to Canada including my only valuable items. Two plates from the Ming Dynasty.

AA: Wow.

WP: And that was actually my emergency fund. My friend gave it to me when I left China saying, “if you can’t make it, just sell these so you can buy a plane ticket back to China.” I arrived in America with $26 in my pocket. So anyway, that professor, my fiancé convinced me to take the GMAT and to apply for admission for the MBA at McGill.

AA: For an MBA?

WP: Yeah, MBA. I actually got accepted with no math. I don’t know how I passed. I actually scored pretty well on the GMAT even though I have no math. But they did give me the condition that I have to take a year of math. And they knew I had no math somehow, you know, so I shipped everything already to Montreal. I was planning to get an MBA and get married and become a rich businesswoman, right? And in Grand Central Station, I just thought, no, I can’t do that. But my choice was, I have nothing left. I had no place to go to sleep that night and no job. I had nothing. But somehow this internal voice just said, I recalled the Little Mermaid voice. Like, “You have to go after your dream.” So I did not board the train. And of course I lost my two antique treasures. Never saw my fiancé again, he was really mad.

AA: Why did you lose the plates?

WP: He refused to give it to me.

AA: Oh my gosh.

WP: He said that he locked it in the cabinet and it fell and everything broke. I don’t think so.

AA: And you just walked away because it wasn’t worth trying to get him back from him?

WP: No, no. Well, I do feel a little bit bad because I broke the engagement, you know. That’s okay. You know, that’s my price for poetry. And so meanwhile, I had six months to get a green card otherwise I would have to go back to China. Because I had a year after I graduated from my master’s degree from Long Island University. I already wasted half a year because I was planning to get married in Montreal. So I didn’t really look for a job. Then suddenly this thing came, so I had six months to find a job or I had to go back to China. And so what I did, it was so difficult to find a job, a company that would be willing to sponsor my green card. So I looked and looked and finally I thought about teaching. Board of Education. So I went to Brooklyn, to the headquarters of education. I don’t know where it is now. At that time it was in Brooklyn. So I just charged into the headquarters and I just said, “Can someone give me a job? I want to be a poet in New York, I need a job so I can stay, or I have to go back to China.” And I remember the room was just silent, right? Everyone was just stunned.

Then this bearded man looked up and he said, “come here to my desk,” and I went over. And he said, “You are very bold, aren’t you? You don’t give up, right? If I don’t give you a job, you won’t leave.” I said yep. And so he said, “Well actually we need someone bilingual, we have a bilingual gifted program in Chinatown. Do you want this job?” I said yes. So I started teaching poetry with those bilingual kids in Chinatown.

A year later, I got my green card. Actually no, two years later I got my green card. I taught at Pier 1 in Chinatown for two years as a bilingual teacher. Then I decided to go to a PhD program at NYU. And then I graduated, I got my PhD and footbinding was my thesis. And so the minute my thesis passed, I immediately sent it to the University of Minnesota Press and within an hour the publisher, Doug, wrote to me and said, “We want this book, please do not send it anywhere else.” And they agreed to do the index for me.

AA: Wow.

I had no place to go to sleep that night and no job. I had nothing. But this internal voice just said…“You have to go after your dream.”

WP: Yeah. At that time I was pregnant with my second child. And I just got a job at Macalester College and I knew what’s coming. There’s no way I could, you know, and I had a two-year-old toddler, right? There’s no way I could handle two babies, a new job, and work on the index. So they kindly agreed to do it and the book came out. It was quite a splash, and actually got the really competitive award for the Best Book in the Humanities of the year. And also then a lot of lectures, invitations, but also a lot of nasty letters. I remember very clearly I got a letter from London saying, “Wang Ping, you wrote this book, right? You know, you have no idea what you are talking about. You deserve to be pricked by needles.” At that time, London had some guy going around poking people with needles. Do you remember that?

AA: No!

WP: Yeah, it was really funny haha!

AA: Well, we could have done a whole episode on just your life story. I had no idea. This is so incredible, so fascinating and really inspiring. Thank you for sharing all of that. That was just amazing. Thank you. So I have some questions that I wrote as I read the book, and maybe we’ll just go through these questions and you can tell us all about it.

WP: Sure.

AA: The first thing I wanted to say, and we alluded to this at the top of the episode but just about the complexity of this issue. And I wanted to start out just with a note that you write in the introduction of the book and that “The concept and practice of enduring violence and pain, mutilation, and self-mutilation in the name of beauty can be found in almost every culture and civilization.”

WP: Yes.

AA: So this isn’t something that’s specific to China, and I think that’s really important to talk about. My note to that was that I live in Utah now, which is the plastic surgery capital of the United States.

WP: I didn’t know that.

AA: Oh yeah, so much plastic surgery here. And in addition, I’m always hearing women, like when I go to the gym, I just hear women talking about these super excruciating procedures that they get done to their faces just with this obsession of looking a certain way. And so this is an affliction in every culture, including right where I live. So, let’s talk about the actual process of foot binding. Can you tell us how it was done? And then at what age? What was typical?

WP: Usually it depends. Some start the girls at like four or five, typically six, then eight years old is already too late. That’s because the feet have formed, certain lengths are easy to manipulate. Because the process is really painful. So they would push the four toes, leave the big toe out and push the other four toes under the feet, the sole, and then bind it. Use this white cloth to bind and turn the feet into the shape of like little rice dumplings. Kind of, you know, pointed at the big toe then gradually bring it– but also it’s not just to make it narrow, but also have to make it shorter. So as you bind the cross will just go through the ankle and pull it close, just shorten the arch of the feet. So over the years, usually the gradual breaking point takes one to two years until all the bones and the toes are broken. And the arch is also bent and broken.

So the feet will be very thick. There’s a crease in the middle, that is the heel and the toes are finally pushed together. So once that’s done, it will be difficult for women to walk, right? And they need to be bound forever with those binding cloths as a support for them to walk and to stand on their feet. So during the breaking process, the little girl suffers a lot, you can imagine. And not only the bones have to be broken, but the flesh has to be kind of shed away through rotting. So otherwise you can just imagine you can’t allow the flesh to grow out of that. So the flesh has to be, not only bones, bones and flesh just to be broken and rotted away. But at the same time, even though rotting and breaking, the final products, the feet, the skin have to be very smooth. No scars, right? And the shape has to be perfect. And still the woman has to walk with grace on the broken feet.

AA: How?

WP: They practice. You know, like The Little Mermaid, every step is on a knife. They have to endure. And there was a smile and there was grace.

AA: One of the things that was so hard to read about is the dynamic between mothers and daughters. As the mothers are the ones who are doing this to their daughters. And you talk about the Chinese word “téng.” Am I pronouncing that correctly?

WP: Téng.

AA: Téng. Can you talk about that a little bit? That was so interesting.

WP: Yeah. Well, téng means pain. In Chinese culture, the word love is always coupled with pain. Téng ài. Which often is the kind of love relationship between mother and daughter, father and daughter, and husband and wife. Téng ài. So your love was pain.

AA: You write a quote here that kind of develops this, about this pain/love relationship between mother and daughter. You write, “Footbinding murmurs about seduction, eroticism, virtue, discipline, and sacrifice. It also teaches little girls about pain, about coming of age, about her place in this world, about her permanent bonding with her mother and female ancestors.” I thought that was just so evocative and poignant. And I thought of you and your own grandmother with bound feet. And then little six-year-old you binding your feet and how that tradition must just be so complicated with love and pain in it.

WP: Well, it’s not easy to be a woman. And it’s not easy to become a woman in China at that time. In the feudal society in China. Especially once she’s married into a family of total strangers and married to a man who she never met. And immediately, she’s the lowest in the family. She has to serve her mother, parents in-law, that’s a must. And who actually are often very harsh, because the mother-in-law endured so much hardship. Now she’s ready to lash it all out on the new girl, right? And she has to serve the husband. She has to serve all the husbands, like every sibling, and she is really the lowest until she has her own children and she becomes a mother. And a lot of girls, it’s very hard to survive in that new environment for a 13-, 14-year-old. Sixteen is already very old at that time to get married.

AA: Wow.

WP: And so the girls have a very short period of time to learn everything they need to learn before they go to another, to go to a strange place. So you can imagine the anxiety, right? And the determination for a mother to teach everything the little girl needs to know in order to survive and thrive, if the little girl fails in the husband’s family, it will reflect back very badly on the parents’ home. And it is the mother’s duty to teach the girl everything she needs to know and also the personality. And so the pain she endured when she was six is kind of like a prerequisite to what it is going to be like when she gets married. And if she can endure the footbinding, she surely can endure what’s coming at her.

AA: Wow, that’s a level that I hadn’t thought of. So I’m so glad that you talked about that. The thing that I thought of was much more simple and basic. And that’s just that, as you described earlier, this is a culture where if you don’t get married you’re without protection in the world. And so a mother needs to prepare her daughter to be selected as a wife. And it sounds like in some periods of time, in some places, you would not get chosen as a wife if you didn’t have bound feet. Right?

WP: Right.

AA: So this is her way of ensuring that her daughter’s gonna be safe. Right?

WP: Yes. Not just safe, but can survive. You know, just getting married is not the end game. To survive in a new family is just the beginning of life. So they call the married girl the water that you pour out of the house.

AA: Oh, the dirty water?

WP: Well, it’s not dirty water, it’s just that once the daughter is married, it has nothing to do with the natal families. She belongs to the man’s family. Period. So the natal families have not much to say.

AA: There’s another thing that I wanted to talk about before we get to the history of footbinding that I thought was, again, so important. You talk about the written record, like what are you getting your research from, and you write that “Although footbinding was an entirely female practice, the discourse and literature that evolved around it over time were scarce and largely produced by men. The practice had been living as an oral culture exclusive to women who passed it on from body to body, mouth to mouth, handiwork to handiwork for more than a thousand years.”

And I just wanted to ask you about that. What do we know about what women thought about footbinding in their own words? In their own time?

WP: Well, first of all, it’s oral because women were not supposed to know how to read and write. And even though there are quite a number of women poets and artists, and actually a lot of them were either from the indulgence of the parents who had money and the culture education, they would allow their daughter, which is very rare. And a lot of the time it’s the courtesan. They were taught how to read and write and play music and paint so that they can generate more money. So because the majority of women didn’t know how to read and write, the tradition is oral. But in a way, they passed it down through their body. I would say footbinding is kind of like writing on a female’s body. And also their art because they put so much of their creativity into those shoes. If you ever saw those shoes, you’ll be just, wow, this is just breathtaking art.

AA: We’ll have pictures of them on our website. So listeners, make sure to go to the website and look at the pictures that we’ll post there.

WP: And then the culture, what you need to do, when to do it, how to do it, and all the stories along with it, it’s all among women. And then at the end of the book, actually, I devoted two chapters to the female writing. And that is among the Hunan, the central part of China. That group of women, they developed, they invented their own writing. Very vivid and very beautiful. The secret writing. And no man is allowed to learn and read it or see it. They would write it on fans, on cloths, on different objects. And then they will pass this, they would use men as messengers because women couldn’t really walk long distances, right? So men would only be allowed to be their messengers, their postman. So men would carry their secret letters in female writing that they did not know how to read, and send it from village to village, region to region, and then the woman would get together as a support group. They would gather, they would sew, care for their feet, and they would embroider their shoes and they would share the stories written in their female writing. I found that just extremely fascinating, that history. And I have a whole book of their writing right. And when they died, those women would want to be burned, to be buried with their writing with them so that they could enjoy it in their next life. It’s just fascinating.

AA: It’s beautiful. And that really speaks to the point that you brought up earlier about women’s courage and innovation and the initiative that they took in their autonomy in carving out a space for themselves. Even within this patriarchal system and within this system that literally hobbled their bodies, but that they were able to create beauty and community out of that is just really amazing.

WP: Female friendship.

AA: Yeah. Okay, so now let’s talk about some historical landmarks regarding footbinding. If you could tell us when it started and the different dynasties where it gained popularity and how widespread it was? If you could just give us a couple…

WP: Yeah, in a few sentences, it started as the dancer, the royal concubine in the eleventh century. And he was a lead artist, poet, and musician himself. But he lost his kingdom because of that. So he was very indulgent. And he had this concubine who was a great dancer, so he built a gilded lotus stage for her. And she would bind her feet loosely into the shape of the new moon. Just bent and pointed and danced on the lower stage. Then of course, all the other concubines tried to win the favor from the emperor, so they would imitate the dancer, start binding their feet, and pretty soon the war broke out and the royal families had to flee. So they would flee from north towards the south and along the way, this custom kind of started to spread. So another irony is that war often is the engine to spread a lot of culture.

So by the Song Dynasty and Ming Dynasty, footbinding became very, very popular. It spread from the upper class all the way to the peasants. Then by the Qing Dynasty, the Manchu rulers realized that this footbinding somehow weakened both women, physically, and also weakened the mind of men because men were so obsessed with small feet. Some of the men actually began to bind their own feet.

AA: Oh, wow.

WP: Yeah, that’s right. There were quite a few stories about men binding their own feet. So Qing rulers issued many decrees forbidding the Qing women to bind their feet because they realized their own Manchurian woman wanted to bind, wanted to imitate this custom and start binding their feet. They said if you bind your feet, you are going to die, we’ll chop off your head. And the Qing men are forbidden to marry bound-feet women.

AA: What year would this have been? Roughly?

WP: Um, the Qing Dynasty, I would say 17th century. And it’s all the way through. But it doesn’t matter, so the Qing woman would invent a kind of shoe which is like a very high heel but it’s in the center. So with the pants that cover their feet, it gives the illusion that they have bound feet. So they will have the bound feet gait because the high heel is in the middle. So you have to walk in certain ways that sway and you can fall, so it makes them look very fragile, you know? So yeah, there is so much poetry and stories about bound feet, then the feet became a sexual organ itself. And at the same time it’s really interesting, there are a lot of stories about women with bound feet disguised themselves as men and becoming generals, and even pirates. So it’s just really fascinating stuff.

AA: A couple of passages that I’d love to highlight throughout this history, maybe two themes that jumped out to me, and one you’ve already talked about a little bit, but idealizing the woman as weak. That she’s very fragile and that was what they were trying to achieve. So there’s a poem written during the Yuan Dynasty, which is when the Mongolians had taken over China and that was between 1271 and 1368. And there’s this poem called “Song for the Dancing Girl Taking off her Shoes”. And two lines from this jumped out at me. It says, “After dancing on the ivory bed, she reclines with such fatigue like the uneven prints of wild geese left on the sand. The golden lotuses,” meaning her tiny feet, “the golden lotuses too narrow and tiny to walk.” But that was what was idealized, and sometimes you said even in different periods of history, they would bind their feet so tiny, even less than three inches, that they would have to use canes or they would have to be carried around.

WP: Yes. The extreme that people are willing to go for beauty, for status, for power. Well, the interesting thing is that you have to reduce, to cut off your feet to gain power. That’s the idea. It still blows my mind, to be honest with you.

AA: I guess the last piece of the historical timeline that I wanted to have you talk about for a second is the huge shift at the end of the 19th century, when footbinding then became unpopular. So can you talk about that period in Chinese history?

The extreme that people are willing to go for beauty, for status, for power…to cut off your feet to gain power…It still blows my mind

WP: At that time, the Qing Dynasty was falling apart and China was falling apart, divided and burned down. Divided and invaded by colonialism, Japan and all the other European, including American countries. And Chinese men, scholars began to just rise up and they began to go abroad and hope to study technology, which is also the beginning and the middle of the Industrial Revolution. And that’s how the British and the West could conquer China with their guns and cannons and ships. And China was still using magic and bows and arrows. So they wanted to study and then they tried to look inward and they believed that weak women, women with hobbled feet, produce weak men. So they wanted to abolish that, but that was very, very difficult because once you broke your bones, you can’t regrow them. So women resisted greatly. And also at the time, one of the things that came into China with the colonization is Christianity. They set up a lot of churches, so they also started preaching that footing is not good. And then there were some very extreme young people who would patrol the streets with scissors and they would cut off a woman’s binding.

AA: Wow.

WP: Yeah, on the street. It’s like basically pulling off the woman’s pants.

AA: Oh yeah, right. You wrote that in the book.

WP: Yeah, but those humiliated women often had to commit suicide. You know, they couldn’t live because it’s just too much humiliation. So it was pretty violent.

AA: May I read a passage that you wrote here too, because I thought it was so interesting. You quoted a man named Kang Youwei. Am I saying that right?

WP: Kang Youwei.

AA: Thank you. In 1898, he wrote, “All countries have international relations so that if one commits the slightest error, the others ridicule and look down on it. Now, China is narrow and crowded, has opium addicts and streets lined with beggars. Foreigners laugh at us and criticize us for being barbarians. There is nothing which makes us objects of ridicule so much as footbinding. I look at Europeans and Americans so strong and vigorous because their mothers do not bind feet and therefore have strong offspring.”

So as I read that passage, I have really mixed feelings honestly. I mean, on one hand I am not a fan of footbinding and I think that his criticism of footbinding is valid. But on the other hand, it kind of breaks my heart that it’s like he has internalized this colonial way of viewing his own country. I mean, he seems so self-conscious and embarrassed of all of China’s struggles with poverty and opium addiction and just feeling like, “oh, foreigners are laughing at us and criticizing us.” I mean, it just breaks my heart that he’s feeling that way about China when of course every country has its struggles with poverty and with things like that. But the US at the time, it was what, 1898? The US at the time, I mean, women weren’t allowed to vote. Women weren’t footbinding, but they had restrictive clothing that they were wearing and there was a huge poverty problem. And it had only been a couple of decades since Black women were literally enslaved in the United States. And you have women being exploited in factories and the big cities. And anyway, the United States had plenty of problems, so to say that the Western countries are so advanced and we are so backward, that just wasn’t the right argument against footbinding because it wasn’t based on fact. And it was a sad, colonial way of viewing his own country.

WP: Thank you for being aware. To be honest with you, this colonial mindset is still very prevalent. I encounter that all the time still.

AA: Is there something that you would like to talk about, like a final takeaway?

WP: You know, I’m glad we talked about colonialism. In a way it’s kind of ironic because the footbinding looks kind of like the ultimate oppression of women. But if you really look into it, women are powerful. I actually want to add that in the short period of the girl’s life with her mother, the girl has to learn everything she needs to know, right? And because of this kind of training and lifestyle, I’m not saying this is good, right? Nobody deserves to go through such extreme pain, but it also makes Chinese women very, very strong and flexible. And that’s part of the reason why Asian women can survive and thrive in any other culture.

We actually can be more successful than in our own native countries. So I think it’s because of that kind of training. I grew up very harshly in China, with no water, no electricity, and no heat, and I was beaten a lot for every book I read. But it made me who I am now. Joyful. It made me realize joy, you have to go through a lot of suffering and pain to really learn what real joy is. And we have the power to transform suffering. The signature life is, in a way, is pain and suffering, but it does not have to remain that way. We have the power to transform it through the arts, through poetry, through music, through living life with this attitude that we are our own agents. We are agents, right? We have the agency to turn things around. We have the attitude. And then we can survive and thrive wherever we go or under any circumstances.

AA: Well, what a beautiful way to bring our conversation to a close. Dr. Wang Ping. I am just filled with admiration for the way your life embodies all of those principles that you just talked about. I’m grateful for your book, I’m going to be looking up all of your other books and your poetry.

WP: Oh, thank you.

AA: I’m just so grateful for this conversation and I’m so happy that I found your book. I would highly recommend it to listeners. And again, thanks for being here today.

WP: Thank you. Thank you so much!

if she can endure the footbinding,

she surely can endure what’s coming at her

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!