“Don’t see them as your enemy, see them as your future ally”

Amy is joined by activist and advocate Troy Williams to discuss his incredible coming out journey from the Eagle Forum to Equality Utah, plus how changing our perspective can help turn enemies into allies, and why people of all identities are needed in the struggle for equality.

Our Guest

Troy Williams

For the past two decades, Troy Williams has been a community organizer playing pivotal roles in passing laws and protections for the LGBTQ community in Utah, including the historic Utah Compromise, a statute against LGBTQ and racially inclusive hate crimes, and a ban on LGBTQ conversation therapy. In 2010, he co-wrote the award-winning play, “The Passion of Sister Dottie S. Dixon” with the late Charles Lynn Frost, and has since worked on various movies and series centered around real-life stories and people from the Mormon faith. He became the executive director of Equality Utah in the fall of 2014 and was named one of the nation’s 50 LGBTQ Champions of Pride in 2022 by The Advocate magazine.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In 2014, a poll was conducted in Utah to see what percentage of the population supported same-sex marriage. The results indicated that 40 percent of Utahns supported it. Ten years later, in 2024, the same poll was conducted again, and this time 72 percent of Utahns supported marriage equality. How did this happen and how did it happen so fast? To talk about this issue and other issues, I am so thrilled to welcome to the podcast, Troy Williams, the head of Equality Utah. Thank you so much for being here, Troy!

Troy Williams: Amy, it’s my pleasure. I’m so excited to spend some time with you.

AA: I’m so excited too. This is fun to have a reason to spend an hour together. But I’m really, really excited to hear more of your story, too, and also the story of Equality Utah and the changes that are happening. I’m super excited to dig into that. But first, I’m going to read your professional bio and you get the task of just sitting and listening to me sing your praises while you sit there and squirm awkwardly.

TW: Aw, alright. Take it away.

AA: For the past two decades, Troy Williams has been a community organizer for LGBTQ Utahns. In 2003, he became the Community Affairs Director of 90.9 FM KRCL radio station, and executive producer of the talk show Radioactive. In 2010, The Salt Lake Tribune dubbed Troy “the gay mayor of Salt Lake City”. That’s pretty awesome, and that is a title I did not know you had, Troy. That’s incredible.

TW: I did not run for that office, I will confess.

AA: That’s amazing. I want a plaque somewhere. In 2010, Troy co-wrote the award-winning play The Passion of Sister Dottie S. Dixon with the late Charles Lynn Frost. In 2011, Troy appeared in the scandalous Errol Morris true crime Mormon noir film Tabloid, which detailed the alleged kidnapping of an LDS missionary by a Wyoming beauty queen. This is the best bio I think I’ve ever read, Troy. Holy cow. You’ve done amazing things.

TW: It’s not over yet!

AA: In 2013, Troy produced the TLC original series Breaking the Faith, which followed the lives of FLDS youths on the run. And in 2022, Troy was a consultant on the FX series Under the Banner of Heaven with Andrew Garfield and director Dustin Lance Black. Troy has also appeared in the HBO original films Believer and Mama’s Boy. In 2022, The Advocate magazine named Troy one of the nation’s 50 LGBTQ Champions of Pride. Troy became the executive director of Equality Utah in the fall of 2014, and in 2015 he helped pass Utah’s historic Utah Compromise, which successfully balanced LGBTQ non-discrimination protections with religious liberty. In 2016, he led efforts to rename twenty blocks of downtown Salt Lake City as Harvey Milk Boulevard. I was just there yesterday and noticed it again, Troy. I’m so moved by that, it was so awesome to see that signage. In 2019, he worked to pass an LGBTQ and racially inclusive hate crimes statute. In 2023, his team successfully passed legislation unanimously through the Utah legislature to codify a ban on LGBTQ conversion therapy for minors. That’s amazing, Troy. You’ve done some fun and crazy interesting things, and then so much incredible social justice work. Again, I’m super honored to know you and I’m really excited to have you talk about this more in depth on the podcast today. I’d love you to tell us your story, where you grew up, your background, your education, and some of the things that were formative in making you who you are today.

TW: Yeah, thanks. I grew up in Eugene, Oregon. I grew up in an LDS family in a very liberal town. Two of my best friends in high school were LDS, and they had a different path from mine. They actually were encouraged to go to conversion therapy, and it had a very destructive impact on their lives. It was very painful for me to watch them go through that, and it really pushed me deeper into the closet as a teenager. I was very afraid of what it might mean about me. So I stuffed that down pretty deeply while I was, you know, listening to my Erasure and Depeche Mode. I had Yazz albums as a teenager in the ‘80s. And then I sublimated all of that by going on an LDS mission for two years to England. And when I came back, this nascent thing was still within me and it was getting stronger. You’re in your early twenties and your hormones are surging. And I was so afraid that I was gay that I thought if I moved to Utah, everything would get better, and so I sublimated it even further by joining the Utah Eagle Forum. Now, you have to know the Utah Eagle Forum is this arch-conservative organization founded by Phyllis Schlafly. Phyllis had mentored and trained the president of the Eagle Forum, Gayle Ruzicka, who then became my mentor. And the first time that I ever went to the Utah Capitol was actually with Gayle, as she trained me in her ways. And in the early ‘90s, she was at the height of her power. The gallery in the Senate and in the House, that was her area. As she could look down upon lawmakers, and with a thumbs up or a thumbs down, command them in the vote.

And so I was kind of caught up in that. And I thought that if I just became this turbo-righteous Latter-day Saint, that the goodness and the holiness of my righteous cause would straighten me out. But it didn’t! And I had to go on this journey of self discovery that’s familiar to a lot of LGBT people. Ultimately, I left Eagle Forum and left the LDS Church along that journey of self discovery, and then I moved to the other side of the political spectrum and became kind of a rabble-rouser activist. When I was working at KRCL radio, I would be the kid that was out there organizing the protests, rallies, marches, and the sit-ins and kiss-ins, and famously I was arrested at the Capitol at a protest. So I moved from one extreme to the other, really trying to discover what advocacy was, what activism was, but no one really trained you how to do it. You had mentors, but it was more like learn as you do. And then that ultimately led me to Equality Utah down the road.

AA: Okay, yeah. I want to dig in on a couple of things. First of all, is it okay if I ask when you were younger and you were feeling those beginnings of your sexuality waking up and going, “Oh, okay, this is giving me different information than what I expected,” did you ever consider talking to your family about it? Where were the messages coming from? Aside from your friends going to conversion therapy, which understandably would have scared you, where were the messages coming from that made you think “that’s not safe for me to be that”?

TW: Well, I was a teenager in the ‘80s as the AIDS epidemic was hitting and devastating gay men, and it generated a lot of fear. Because popular rhetoric at that time was that this was God’s curse for the sin of Sodom, and that this was a natural result of this wickedness. And so I believed, as a young Latter-day Saint, that I wasn’t actually gay, but I was actually so righteous that Satan was trying to tempt me, and so Satan would put these homosexual feelings within me. And I had to do a lot of work in therapy as an adult to unpack that. How devious and sinister is that? To believe that that impulse, that beautiful impulse from your heart to connect to another heart, that impulse to love and touch and connect and kiss and hold another human being, which is so innate to who we are as humans, is actually motivated by the devil.

And it’s just not true. But as a teenager, I couldn’t unpack that. I couldn’t understand that. And so I just stuffed it deep down, down, down, down, and I thought that by being super righteous that those feelings would go away over time. So, the messages came from church, they came from popular society, and from my parents. I tell this story, not to make my sister feel bad, because we’ve worked through this subsequently throughout the years, but in LDS culture, one of the former presidents of the church is a man named Spencer W. Kimball, who was a prophet for the Mormon Church where I was a young teen. He had famously, or infamously, written a book called The Miracle of Forgiveness, and I remember my sister handing it to me when I was a young teenager. And in this book, President Kimball makes this astounding and heinous inference. On one page he says that masturbation will lead to the gross sin of homosexuality, and then on the next page it says homosexuality will lead to the even grosser sin of bestiality. And that was difficult for me as a young kid because I grew up on a farm, in this little rural area outside of Eugene, so I was around farm animals. And my brain was like, “What is going on? How can this impulse to love somebody lead me down to such a dark path with sheep?” And thankfully I’ve never been attracted to animals. But that’s the kind of stuff that gets in your head as a little kid.

And of course, back in the ‘80s there wasn’t a lot of good gay representation in the media. I think the first gay character I knew was Steven Carrington on Dynasty. And I think it was the season one finale where Blake walks in on Steven with his young lover and they fight, and then throws the lover down the stairs and kills him! So, you see images of what it means to be gay, and to be gay was death, right? It was spiritual death, to be cut off from the presence of God and from your family eternally. It was physical death, either you’d be attacked or murdered, or you’d catch a disease that would kill you. So, it was a really fearful time. Even though, simultaneously, as I said, I was obsessed with Erasure and The Communards and Bronski Beat, all of these queer artists that really resonated with my soul. I just connected with them and loved them. And my closest friends as a child and as a teenager, all would turn out to be gay, haha. Interestingly enough. One of my best friends as a teenager, Kevin, was not Mormon, and we parted ways when we were 18 and 19. I went on my mission to England and he went on a world tour with Madonna as a dancer on the Blonde Ambition tour. And we’ve come back together since then and we’re dear friends today. Actually, we were together at the Madonna celebration concert in Palm Springs.

AA: Amazing!

TW: Yeah. So I was always adjacent to queerness and it was always attractive to me. It was innate within me. And I’m very grateful for all of that. Ultimately it was that pop culture element and those dear friends that pulled me out of the Utah Eagle Forum, haha, that little detour in my life.

AA: Yeah. Well, I was going to ask about that, kind of those double tracks, because you were really involved politically with the Eagle Forum. I had totally forgotten that, that it was literally Eagle Forum. It’s crazy. Before we get to the political side, which will be next, I was going to ask you, what personally helped you change your path toward being able to rehabilitate from the harm that had been done and been able to reteach your brain that this isn’t from the devil and actually there’s nothing wrong with this? Are there one or two influences or factors that helped you on that journey?

TW: Yeah, there were several influences. Unconditional friends, friends who love and support you on the journey. Because often your friends know before you do and you get bullies who know that you’re gay before you do. Your parents are the last to know. So I just had dear friends that loved me unconditionally, and I knew that I could be out and gay and that I wouldn’t lose them. And when I had that anchor, then I got courageous. I also had to go on a big journey to deconstruct my religious upbringing, and I spent a lot of time reading Mormon history and asking a lot of difficult questions. Because I needed to know what I believed and what I thought was true or not true because, you know, it’s a high stakes thing. To leave it also means to leave your family to some degree, right? There is a huge risk in walking away from something. So I just had to know. I just had to know.

I did have good therapists in conjunction with psychedelics, which can be very helpful in working through some of those difficult things, but I had some deep spiritual experiences. I had a really beautiful experience driving down the street in Provo one day, and I had an Indigo Girls CD in my car. I was listening to their music, I was listening to the harmonies in their voices and the words of their songs, and it was so beautiful, and I had this realization while listening that whatever that force is that we call God, God loved the Indigo Girls and was a fan. And I had this kind of realization that nobody that could create such beauty could be despised of God. And it hit me so hard, I still get chills thinking about it. It hit me so hard that I had to pull over on University Avenue in Provo and just sit there. And I realized in that moment that God loves gay people. God has gay people on the planet to create beauty and art and music and joy. And it was the first time that I realized that. I just had to sit there and feel that in my bones, that God loved gay people. And then I could accept that within myself. And it didn’t all come at that moment, I didn’t open the window and scream to the world, “I’m gay!” and all of Provo heard. No, that wasn’t what happened, but that opened the door. And I remember that just a few days later, driving over Point of the Mountain on I-15, I remember practicing saying it out loud. “I’m ga….” And the next time I got a little bit bolder. “I’m gay…” And then I said, “I’m gay!” And I yelled it at the top of my lungs in the car by myself, and it was a beautiful moment of self-discovery. I felt this freedom to be me, and that’s my coming out story. And then I told my friends.

… to be gay was death, right? It was spiritual death, to be cut off from the presence of God and from your family eternally. It was physical death, either you’d be attacked or murdered, or you’d catch a disease that would kill you. So, it was a really fearful time...

AA: Beautiful. Oh, thank you. Thanks for sharing that. So did that correspond pretty much on your timeline with like, “Okay, if this is true about me then that is going to impact how I view the world politically and the kinds of causes that I want to be involved in”? Clearly you wanted to help change the world. Then it was a pretty hard pivot in a different direction. Did that correlate with that time period?

TW: It sure did. I had this gap in college where I was in such disarray. I went to BYU for one semester and my belief system was collapsing and I knew I couldn’t stay there, so I just went and worked and then I went back to college. And then in college, you know, it’s when you explore a lot of things, do your first psychedelics and all those kinds of things. But for me… I came out when I was in college, and it was actually 9/11, 2001, and I remember that day so vividly, where two planes had struck the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. And I didn’t understand the kind of geopolitics that would lead someone to do such a heinous act. I felt that I had really been self-absorbed trying to figure out this gay thing and this religion thing, and that I hadn’t actually peered out externally to the broader world around me. It’s very easy when you live in Utah and you’re part of this faith just to be absorbed by it. And I was like, “Wow, I don’t understand the world outside my window.” But I didn’t believe that going and bombing Iraq was the right response, I just didn’t like that. So I went to my first anti-war protest and started getting involved and volunteering. And then I think in 2003 I was volunteering at KRCL radio, and we had just launched a new talk show called Radioactive. I just jumped in on the ground floor with it, helped build it up, and I started producing it just as a volunteer for a couple of months. And then within two months of the show launching I was the producer of the show, and then I worked there for 10 years. And that’s a great place to really be mentored by some of the best thinkers for advocacy in Utah, and also nationally and globally.

And then I started getting really audacious. In 2004, the Utah Legislature passed Amendment 3, which amended the state constitution to forbid any form of relationship recognition that was same-sex or gay, or civil unions, etc. Gay marriage was already illegal, but any contractual arrangement between gay couples would not be recognized by the state. And that passed by referendum and it was in response to Massachusetts being the first state, 20 years ago now, to pass marriage equality. So all the conservative states, they kind of panicked and started passing these marriage bans, and Utah was one of them. It was really shocking to me to see that over 60 percent of the state supported the ban into the state constitution, and that was heartbreaking. And that lit a fire under me to be an activist myself. At that point I started organizing rallies and protests and marches, et cetera. And I practiced what it was like to get a bull horn and get in front of a crowd or microphone and work the crowd. It was an incredibly exciting time back then.

AA: Tell us more about radical Troy. What was in your head, how you were seeing the world, and your belief system? What was going to be most effective in bringing about the change that you wanted to see?

TW: Yeah, I like to refer to this as the militant homosexual era. Gayle Ruzicka, my old mentor, set this action alert out to her Eagle Forum list referring to me as a militant homosexual.

AA: Oh wow.

TW: And I thought that was the greatest compliment. I wanted the T-shirt, you know, “militant homosexual”. So I started building this brand around being kind of bombastic and being a sort of rabble-rouser. And there were a lot of theatrics to that, but I wanted to sort of jolt people out of their complacency. I thought that having a more in-your-face approach would be good. And I’d read a lot of LGBT history and so I knew the impact of ACT UP and how important ACT UP was, and Queer Nation. And they were these radical rabble-rousers who would do die-ins and who would do all kinds of dramatic stunts to really draw attention to the urgency of what they were working on. So I felt a lot of affinity for that kind of punk rock ethos of, you know, tear it down and defy authority and be sort of iconoclastic in my approach. So I did and I was, and I think I scared a lot of the kind of establishment gay people a little bit. I was always very committed to peaceful, nonviolent protests. I always was thinking about Gandhi and King, I never wanted to destroy property or instigate any form of violence, but I wanted to be creative and clever and provoke conversation.

I think the first activist thing I ever did, there was this state senator named Chris Butters. He was this cranky old senator and he would say heinous things. He would pass out literature on the senate floor talking about all these pornographic, disgusting, fetish things that had nothing to do with gay culture, but really it was about fetish culture. And then he got up and famously he said that the gays were worse than Muslim terrorists. And he was lampooned on late night shows because he said, “I don’t mind the gays, but they keep shoving it down my throat!” So my first activist stunt I ever did was a thing called Butterspalooza. We threw this big party at the Capitol. I made it very clear that I wanted it to be a party so we brought a blues band and DJs and break-dancers and drag queens, and threw this big party up at the Capitol to celebrate Chris Butters uniting all the progressives in Utah. We had union organizers speaking, climate justice folks speaking, and queer people speaking. It was this very full-spectrum social justice, that’s how I think about it. But it was fun and it was joyful, and that caught on a lot of attention. That began to shape my advocacy. I was militant, I was in your face, I was angry, but I was also fun. I always thought about the great anarchist Emma Goldman, and she famously said, “If you don’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” And I loved that because I always wanted people to feel like they had a place at the protest, at the party, at the celebration. That if we danced, and centered joy alongside our outrage… You needed both. That if joy and outrage could coexist, that more people would come along with us. So that became my style of advocacy.

AA: Okay. And did it evolve from there? I think that some things probably have stayed the same and you definitely stayed true to some core values and even some tactics, it sounds like. But I think some of your tactics have changed. How and why?

TW: Yeah, yeah. I had an experience in 2012 that was really life-changing for me. If you are familiar with Dustin Lance Black, he’s a gay Mormon filmmaker and he won the Oscar for the screenplay to the Harvey Milk film. Lance and I also worked together on Under the Banner of Heaven. He’s a close friend of mine, and he was the Grand Marshal for our Pride Parade in 2012. In the context of this moment, 2008, Proposition 8 had passed in California, the LDS Church was a major funder and organizer for this, so the tensions between the LGBT and LDS communities were at an all-time high. We had protests at the temple, we did kiss-ins on Temple Square and all kinds of direct action pieces. So there was a lot of tension, and this group of Latter-day Saints called me up and wanted to meet with me. I agreed to it, so I went to the old Pride Center, and it was Erika Munson and Kendall Wilcox, and they had formed this group called Mormons Building Bridges. And they said to me, “Troy, we’re going to march in the Pride Parade, we’re number 84 in the parade route, and we’re going to wear our church clothes and we’re going to sing hymns all the way down the Gay Pride Parade.” And I just looked at them and I said, “Have either of you ever been to a Gay Pride Parade before?” And they looked at me and they’re like, “Well, no.” And I was like, “This is not the Days of 47, this is the Gays of 47. It’s a very different experience.”

I appreciated the gesture, but I was worried and I initially thought it was a bad idea. I had visions of tomatoes being thrown at them, and I didn’t want that, so I was worried about how they’d be received. Lance Black came, and we were talking about what to do with these Mormons at the back of the parade. What do we do? And he’s like, “Why don’t we just bring them to the front of the parade with us and we’ll march together?” like an echo of the Civil Rights Movement. The great symbol of the Civil Rights Movement was the Black hand grasping the white hand and that they’re together in solidarity. “Why don’t we follow that spirit and the gays will march with the Mormons?” It was a risky move, but it felt like the right move.

So on that beautiful June morning with the beautiful blue skies, over 300 active Latter-day Saints showed up at the Pride Parade in their white shirts and their floral dresses and their scriptures with these colorful signs that said, “LDS hearts LGBT”. One sign said, “Sorry we’re late!” And we started to march down the parade route. There were tens of thousands of people in the crowd watching, and they just started to cheer for them. And on every block we went, the crowds got bigger and the cheers got bigger, I was crying and Lance was crying and all the Mormons were crying. People would run out from the crowd and they would hug people marching because, you know, you think about these culture war debates, they divide and break families. So many families who are religious have LGBT family members, and these political things cause rifts and wedges between family members. So this moment to me was transformative and it opened my heart in this big way. I thought, this is how we do it. We do it with love, we welcome people to the party, we welcome people to the march, and we sit with people who we think are our enemies and we march with them as allies. And that day transformed my entire approach.

AA: Amazing. What’d you do then? I’m trying to remember on the timeline when you joined Equality Utah. Because I feel like that’s a hallmark of the work and the strategy that you’ve used at Equality Utah.

TW: Yeah. I mean, I could say whatever I wanted to say on talk radio, but it was great to actually implement it into actual policy and practice. My predecessor at Equality Utah was Brandy Balkin, and Brandy was a dear friend of mine. She took a job out of state, so the position came open. And I had just been arrested at the Capitol at this big protest, so I think the board of directors was like, “Gosh, this Troy has a reputation for being kind of a bomb-thrower and a rabble-rouser. Should we put him in charge of our organization that’s about finding common ground?” And I had to ask myself that question too. Can I put on a suit and tie again – which I call my “lobby drag” – and go up to the Capitol? And for those of you who don’t live in Utah, the Utah legislature is at any given year 85 percent Republican and usually about 90 percent Latter-day Saints. So how on earth would I go up to the Capitol and encourage lawmakers to pass legislation that would bring rights and liberties and dignity to LGBT Utahans. How do we persuade people to rethink their position and consider another way of approaching this? So it was a big leap for me, and I think a big leap for Equality Utah.

I took the position, they gave it to me, and pretty quickly I was thrown into the fire. I was hired in September of 2014, and by January of 2015 I would be in very high-stakes negotiation with the LDS Church and Republican leadership on what was called the Utah Compromise, which was a historic piece of legislation to provide employment and housing protections for our community. I had a lot of pain in my body and my heart with the LDS Church, with the rifts that these ideas had caused in my own family. I was not estranged from my parents, but I wasn’t close to my parents because of these issues. So to find myself literally with the patriarchy in negotiations and wanting to do something that was meaningful, that would move us forward, that would help heal some of the divisions, and being so desperately afraid of failing…. Afraid of failing my family, afraid of failing my community, afraid of the organization, and afraid of falling on my face. And I’m very proud of what we did. It was to me a sort of culmination of a lot of things that had prepared me for that moment.

AA: Amazing. The feeling that I get when I imagine that, I describe this as a woman going into situations like this where it’s like a room full of men, or a situation where I know that I am being viewed in a lower place in the hierarchy, the work that I have to do to fight to say, “I know you see me as less than you and I do have less power structurally, but I’m approaching you with the energy that I know I’m your equal.” Did you have to do work? Did it feel that way to you? I feel like Queen Esther coming to the king, and he raises the scepter and you live, but he lowers it and you die. How do you steel yourself for that?

This is how we do it. We do it with love, we welcome people to the party, we welcome people to the march, and we sit with people who we think are our enemies and we march with them as allies.

TW: Yeah, I remember when all the emotions were up and all the fears were up, and I would have to think to myself, “Don’t see them as your enemy, see them as your future ally.” I would mentally tell myself that. And I remember having one of my first meetings with the Church, and it was very tense. It was one of those meetings where we were trying to talk through things, but then they started digging in on the issue, and then I started digging in on the issue, and my attorney started digging in. We could feel the room getting more tense and more, you know, what are we going to do? My board chair at the time was Professor Cliff Rosky, he’s a constitutional law professor at the University of Utah, and he’s also kind of a Buddhist, so he would coach me through it. He’s like, “Stay in the conflict. When you hit these moments where you want to turn away from each other, when you want to shut the door, when you want to walk out, that is the moment where you have to stay engaged. You have to lean into it, stay with it, and stay through it until our path opens up.” So he would coach me through that, and that’s what we would do.

And believe me, these were not easy conversations. They were hard, and there were several times when I thought, “Oh, this is all going to fall apart, there’s no way that this is going to come together.” But I followed Cliff’s voice in my ear, “Stay in the conflicts, stay engaged, don’t shrink back from it.” And I think there’s also a lot of, well, can I trust these men? And I think that they felt the exact same way. Can I trust this gay apostate? This is a man who knew the truth, he was born under the covenant and he’s rejected it. Can we trust him? So it truly was a leap of faith to try to figure out how we could pass a piece of legislation that would protect gay and transgender Utahns from being evicted from their homes or fired from their jobs just because of their sexual orientation or their gender identity. And can we also respect religious liberty along the way? Can we balance those two things?

I got criticism from all sides. The Church was getting criticism, like, “Why on earth are you talking with Equality Utah?” And the conservative religions were attacking them, Cato Institute would go after them, other folks did. I was getting attacked by the Left, you know, “Don’t sit down with the enemy, you’re going to betray our people.” So it was this really fraught moment. But the one thing that my dad and I had in common, maybe the only thing that we ever bonded on, was Star Trek. And if you remember Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, the premise is that there’s this historic coming together of the Klingon empire and the Federation, because the war has to stop and they have to come together. It’s an allegory for perestroika and the fall of the Berlin wall. There was this conflict with the Klingons and the Federation coming and sitting down around the table to negotiate peace, and there were people on both sides working to sabotage the peace. And I thought about that a lot.

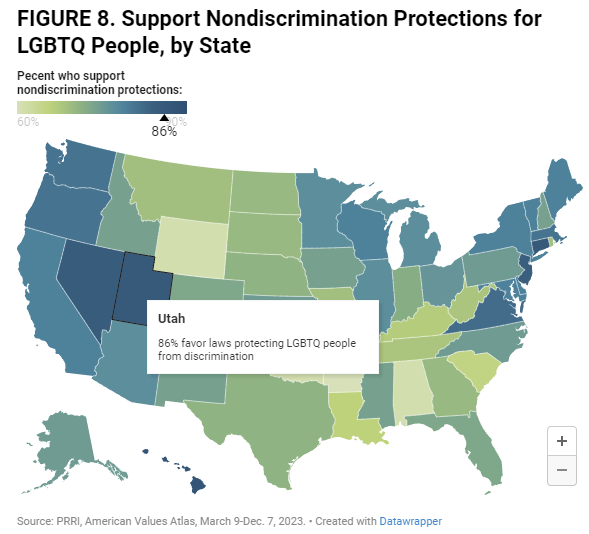

I’m not saying who the Klingons were in that scenario, but I just thought about how difficult it is to create peace with people who have been cast as each other’s enemies and people are suspicious of it. And sometimes people don’t want it, right? Because they want their wounds and their hurts. So to me, it was essential to be in that space and to really work to make sure that there were lines that I wouldn’t cross. I articulated those very closely to the Church and to other state leaders, and we stayed true to that. I think at the end of the day, we created a bill that I’m very proud of and that has really broad public support. Ten years later, just to flash forward, just a couple of months ago, there’s an organization called Public Religion Research Institute, and they track social attitudes across the country. How do they feel about gun issues, abortion, immigration, LGBT issues, et cetera. And they’ve been tracking data on the Utah Compromise and on non-discrimination laws across the country, and what they found in 2019 is that Utah had the second highest percentage of support for public non-discrimination laws for LGBT people. 77 percent of the state. That was the second highest in the nation.

AA: Crazy.

TW: I thought that was odd, I thought that might be an outlier for the year. But by 2020 that number had risen to 80%. And then just a couple months ago, they released the new data and about 86 percent of the state of Utah supports the Utah Compromise, supports that non-discrimination law that we’d made ten years ago. So I do see public sentiment moving and shifting toward us. And to me, it was that respectful manner with which we engaged. We did it in a way that wasn’t a winner-takes-all approach. We respected religious liberty together with LGBT non-discrimination protections, and I think that created a lot of goodwill that allowed us to subsequently pass several more pro-LGBT bills in the Utah legislature.

AA: Well, that was my next question, so that was perfect. I was going to return to what I opened with in the episode, which was this massive shift specifically on the topic of same-sex marriage within ten years. And the numbers just astound me because of what I guess my presupposed notions of what Utah is going to be.

TW: Right.

AA: It kind of has proven it wrong. So I was going to ask you that, on that specific issue of same-sex marriage or the prohibition of conversion therapy and stuff like that. I’m just assuming that it was this same approach that allowed you to make those changes as well.

TW: Yeah, so after the non-discrimination law was passed in 2015, two years later, Gayle Ruzicka, who in 1997 had passed the Don’t Say Gay law, which prevented teachers from talking about gay issues in the classroom…

AA: Okay, that’s going to come as a surprise to some listeners. I think of this as being a new thing and it’s just in Florida, right?

TW: Gayle was the early adopter back in the ’90s. But flash forward 20 years to 2017 and we repealed that in the Utah legislature almost unanimously. There was only one dissenting voice in the House and one dissenting voice in the Senate. So it almost unanimously repealed that law while Gayle watched it happen. It was a pretty amazing experience. And then flash forward to 2020, we passed an LGBTQ-inclusive hate crimes law, which people have been trying to get done in the state for 20 years, and we finally pulled it together. Many people made that happen, and I was proud to be part of that. And then in 2023, just last year, the Utah legislature unanimously voted to ban conversion therapy. And it was all of us sitting down around the table having really hard conversations. There were many moments where I thought I was going to fall apart, but then again, the voice of Professor Roski in my ear saying, “Don’t disengage, stay present, be in this moment, work through the conflict.”

And sometimes you’ll have two sides that are stuck. And if you stay engaged, inevitably a third path starts to open up that you can both agree on. You couldn’t see the possibility beforehand, but then it opens up and then you move through it and you bring people along with you. It was one of the proudest moments of my life. When I thought back to my friends who had gone through conversion therapy, to be able to actually ban this practice in Utah was very important to me. And even more important than the state law, to me, was the LDS Church actually changing direction on this issue. In their Bishop’s Handbook, they actually have a prohibition globally about bishops sending their members to conversion therapy now. These issues are slow going and sometimes the rate of change is frustrating to many people, but progress is happening and I think we have to acknowledge that. Acknowledge that work still needs to happen, but we also need to recognize the victories when they come along.

AA: Yeah, amazing. Could you zoom in on a moment or two, I know we’ve talked about your broad approach of refusing to see people as enemies and to approach with love and good faith, and seeing why this person thinks the way that they do, seeing people in their full humanity. So those are the overarching themes and ethos of it. Take us into a moment or a specific strategy. I’m wondering if there are things that you did to build empathy or to actually open their mind to create a willingness to find a third path with you. Because I can hear from your side why you are willing to come to the table, but what did you do to get these people to be willing to do that with you?

TW: That’s such a great question. To me, it is so essential that we don’t label our opponents as bigots, haters, homophobes, TERFs, whatever thing that we can come up with. Because then we lock them into an identity that may or may not be true, and doesn’t really allow them to evolve and grow. At Equality Utah, we think a lot about how we deactivate the amygdala when we’re in conflict with people. Because we come in hard, people go into fight, flight, freeze, or fawn, right? And so do we. The adrenaline starts surging and we want to go into combat mode or we just don’t know what to say. So we work a lot to talk about how to deactivate that so that people can actually let their defenses drop and be able to talk. How that starts is with you. My amygdala needs to take a backseat, my defenses have to drop, and you do that through curiosity. Eddie Izzard is a friend of mine, she’s an international transgender comedian, and she was performing in our gala a couple of years ago. And she said, “We have to be brave and curious, and not fearful or suspicious.” We have to be brave and curious, not fearful or suspicious. And that was the earworm in my ear. I took her voice up to the Capitol with me all the time. I started asking myself, how can I be brave and curious with lawmakers?

Just a quick backstory. We had banned conversion therapy in 2020, but we did sidestep the legislature and did it through the Therapist Guild here. And there were some lawmakers that were upset about that because they had the rulemaking governance and we had sidestepped that, and they were angry with me. So some lawmakers had introduced a bill to strike down that administrative rule with the Therapist Guild that would have effectively relegalized conversion therapy in 2023. And I was devastated. Oh my gosh, this was something where I thought that I had done something clever and worked around them, but it was really a tactical mistake on my part. So these lawmakers were preparing to strike back. And then Eddie Izzard was in my ear and kept saying to me, “Be brave and curious, not fearful or suspicious.” Because my go-to impulse was to say, “Why are you such homophobic bigots? Why do you want to kill gay kids?” That was the impulse in my brain. But I knew that if I had said that, their defenses would have gone up.

I had a meeting with one of the lawmakers and it didn’t go well. The first time we met, it didn’t go well. I raised my voice and I walked out of it. I kind of failed that interaction. You know, I’m not like a master of this. I screw up and I make mistakes. I failed in my first attempt, and I went off after, like, “Oh, I just screwed this up.” So I called them back up a little bit later and said, “Can I come talk to you without our attorneys and without your? Can I just talk to you?” So I went in and met with this representative, Mike Petersen, and we just started talking. I started asking him about his family and his background, and when I got curious about him, he started getting curious about me. Then after getting to know him, I could say, “Tell me about your concerns over the conversion therapy issue.” And he said, “Well, Troy, I don’t think conversion therapy works. But I’ve got a lot of therapists who don’t know what the line is, they don’t know what the rules are because it’s vague. People don’t know what they can say. We need some guidelines.” I’m like, “Oh, we can come up with guidelines. We’ve got good therapists, we’ve got all the good people. We can all come together. We can work on guidelines together.” And so he’s like, “Okay, well, let’s do it!” And we had help, people like Governor Cox, we had other people saying, “Hey, get everyone together,” really rallying us to come together on this issue.

So we sat down together and created some guidelines that were fair and we created a robust ban on conversion therapy for minors. But it required that I had to let my defenses go and I had to see the humanity of my opponent. My first impulse was to see him as a homophobic bigot. I was wrong. I needed to see his humanity and then he could see mine. And now we have become friends. We don’t agree on hardly anything politically, but we agree that we like each other and that we want to keep that healthy relationship going. And maybe there are opportunities in the future to do even more good work together on legislation. That was a really beautiful moment in the gold room of the Capitol, bringing conservatives and liberals together, signing this legislation. And for the friends of mine and for the people that I know who have gone through conversion therapy, they have deep wounds and deep pain, but we’ve done something to prevent the next generation from experiencing the same. So I’m grateful for that.

AA: Amazing. What would you say to someone who would argue with your approach by saying how unfair it is that you, as the person approaching the people in power, that you, who have been so wronged historically, are the one who has to do all of the emotional and psychological work? To be like, “I will be humble, I will be curious, and I won’t be judgmental. I will work on myself in order to approach you to make peace.” I know people who work in racial justice, gender justice, and class justice, all across the board, who will make that argument and say that that’s not fair. And it’s not, right? How do you respond to that?

TW: Oh, life ain’t fair. But for whatever reason, I signed up for this work and it certainly is not for everybody. It does take a certain temperament, and I don’t recommend that everyone do what I do there. There are some people that just emotionally can’t carry that burden at a certain point in their life. I certainly couldn’t have carried this burden 20 years ago, but I prepared myself, like I said, through lots of therapy, a few psychedelics, a few things to prepare myself spiritually and mentally and emotionally so that I could do this work. And to me, it is a conscious act of healing. It’s a way to heal my family. It’s a way to heal my community. It’s a way to heal, hopefully, the state and the country. And I just feel called to it. It’s something that’s part of my Mormon upbringing, you know, we grow up believing that we are here for a purpose and that we actually have a calling to a thing that we have to fulfill in life. And I feel that still. I want to be an agent of peace and an agent of change, so I have taken on this burden. And it is not easy, it is often painful, and there are moments when I break down and I cry and I am furious and full of rage. And I’ve got some close friends that allow me to call and be completely inappropriate with what I say, I can bitch and yell and be politically incorrect, I can say whatever I want to say to get it out of me. And then I can go back and have conversations with lawmakers and the media. And there are times, like I said, when I have lost it. I haven’t been perfect at this work at all. I have screwed up and messed up and some people have shown me grace and have given me a second shot when I maybe haven’t deserved it. So I’m grateful for that.

AA: Yeah, well, it won’t come as a surprise to listeners that you and I are extremely aligned. And you and I both know this about each other too, because we’ve talked about it personally. But this is the great guiding ethos of the civil rights movement, too. And not just the big moral structure behind it, but the specific training that they would go through. You’re describing the great project of love that Dr. Martin Luther King espoused and made historic changes that way too. It’s something that I think could actually be the only thing that could heal our country right now and the way the whole world is going. It moves me to tears to hear you talk. I wish that there were some ways to do trainings like this for people on a really large scale, because I think this is what’s missing in our discourse on all levels. In our families, in our friendships, in the legislature, on social media. I think that approach is what is missing and I’m worried for the direction it’s taking us, honestly.

TW: A thousand percent, me too. I sought out a mentor, a woman named Irshad Manji, and she wrote this really great book called Don’t Label Me. She has what she calls her Moral Courage Project, and it’s really about how to have conversations across ideological divides, but to do it in a constructive manner, and she’s taught me so much. A lot of my staff have gone through her training program. For example, last year, Equality Utah decided to get a booth at the Republican State Convention. Ron DeSantis was the keynote speaker and was rather bombastic and inflammatory towards LGBT issues. So we thought, well, we’re going to get a booth. We’re not going to protest outside, we’re going to be inside talking to delegates. So we worked with Irshad on this and we did that kind of civil rights training. We role-played as a staff, and Irshad would yell at us. She would say, “Why are you grooming children? Why are you pedophiles?” And we had to practice teaching our emotions how to deactivate the amygdala and to respond with curiosity. “Tell me more about that.” I have a staff member who’s a beautiful transgender veteran of the Air Force, a Latina immigrant, and I was like, “Oh, Olivia, I don’t want you to go to the convention. I don’t think that you’ll be safe.” And she’s like, “Troy, I served in the Air Force for 20 years and I’ve been to Iraq and Afghanistan. I can handle some MAGA delegates.”

So we all went and we bought these big coolers of Diet Coke, because Mormons love Diet Coke, and we started handing out Diet Cokes and having conversations. We were packed the entire time, having intense conversations, and we just asked questions and were curious about where people were coming from. “Tell me why you feel that way. Help me understand that.” And then in the dialogue, find some glimmer of common ground, some gem statement that you can grab onto and say, “Oh yeah, I feel the same way.” Or “I understand where you’re coming from with that.” It was miraculous to watch people coming in hot and then all of a sudden the energy just dropped. And then people would pivot and say, “I have a lesbian daughter that I’m estranged from. What kind of advice do you have for me? How can I connect with her?” And those conversations were one after another after another. We had one guy yell at us for grooming children and within ten minutes he was apologizing and we hugged it out, and we had these great conversations. It wasn’t that I expected to change anybody’s mind at that moment, but if someone can hear that you are respecting them, that you are listening to them, then it shifts the energy and then you can have a real conversation. Maybe they’ll walk away and meet a gay employee or neighbor and their attitude might shift towards them, or maybe they’ll become more curious about them and then that dialogue will continue. So, I’m a firm believer in this approach. It is difficult though, and it’s exhausting. I’m a big introvert, so I’m exhausted after I have those interactions, but I also find them so rewarding as well. We went back this year to the Republican Convention as well, and I had more intense conversations. I just believe in showing up into all the spaces where we’re not expected, reaching my hand out and saying, “Hey, what do we have in common? I know we disagree about things, but what do you think we have in common?”

AA: Well, the amazing thing is that it works. It really seems to be the only thing that does work if your goal is moving forward, if your goal is healing, if your goal is finding compromise. And in a democracy, I think that’s…

TW: That’s what we’re getting at. I think a lot about, like, what’s our objective? What’s our goal? What do we want to achieve? And what I desire is a healthy American pluralism. We have people who will always be conservatives. There will always be liberals and various variations within. There’s always going to be gay and queer people and straight people, and religious people and atheists, and somehow we all have to figure out how to get along. We all have to coexist. We’ve been able to do that for the most part, give or take a civil war here or there. But for the most part, as a nation, we’ve been able to sort of come together across differences. And when we see injustice, the beautiful thing about America is that we keep working to create that more perfect union. Whether it was the abolition of slavery, the suffrage movement, the civil rights movements, the women’s movement, the LGBT movement, we’re always trying to make sure that the liberties and the blessings of this country are available to everybody. And when we see that people are excluded from it, we work to expand the circle to bring them in. That’s America at our best. And I just have to believe that we can get there again.

When you get hired at Equality Utah, you get a couple of books you have to read. One is Irshad’s Don’t Label Me. Another one is Arthur Brooks’s Love Your Enemies. He wrote that book recently with Oprah. He’s more of a center-right person, which is important for my staff to read someone who’s more right leaning. But it’s a brilliant, beautiful book and he talks a lot about how we’ve developed this culture of contempt, that we see our opponents not just as opponents, but actually as evil, as people who are trying to destroy the country. And what he makes clear is that the other side thinks of us the same way. He talks about this concept, it’s very academic, I think he called it “motive attribution asymmetry”. That in a conflict, whether it’s within nation states or between couples, when we get into conflict, we believe that we are motivated by love and truth and righteousness and the other side is motivated by hate and greed and spite.

So I really began to think about that when I sit down with people, whether I’m sitting down with leaders of the Church or legislators or the governor. I thought, what if I truly understood that they believed that they were motivated by love? How does that change how I engage with them? It was very different. I may not agree with their position on something, but everyone believes that they’re the hero in their narrative, right? Everyone believes that what they’re doing is right. I have a lot of disagreements about what the legislature thinks about transgender people, but I understand that they believe that their position is the correct one and is the true one. So I want to be curious about that, and if I can be curious about that, and respect their fears or their concerns, maybe then they’ll be open to hearing my point of view and then perhaps considering another way to see something. That’s my hope, is to be able to shift the certainty with which someone holds onto a position. Just to spark a little bit of doubt and curiosity on their end, which requires that I can’t always be locked into certainty on my end. I have to be open to maybe revising my point of view if I can get different data, and not to be blown by every wind of doctrine, but to actually be open to the thought that maybe my opponent might have something that I need to learn as well. What a radical, crazy idea.

AA: It totally is, and it’s totally counter to human nature. But that’s the way I want to live too, because the other way of living is too limiting, even just intellectually. To think that I already have all the answers and to not have intellectual humility means that I’m going to be limited in my potential to gain wisdom in life.

if someone can hear that you are respecting them, that you are listening to them, then it shifts the energy and then you can have a real conversation

TW: It’s often said that liberals have the truth that conservatives are missing, and conservatives have some truths that liberals are missing, and together we become whole. And I like to think about that. There is this idea that progressives are always pushing on the gas pedal and conservatives are hitting the brakes about progress. And there are mutations of it, there is fascism, there is extremism, and there’s extremism on all sides. And those mutations need to be taken seriously and not discarded. If someone is in fact very violent towards LGBT people, I’m not going to encourage my staff to go in and meet with the Proud Boys. But I want to be careful and not just assume and lump everybody into that. Everybody who disagrees with me is a fascist. That’s not true. Everyone who disagrees with me is a bigot or a racist. That’s not true. I have to be willing to ask myself and interrogate my own beliefs and my own thinking.

AA: All right. Well, to wrap up, I have two quick questions for you that I want to make sure that we hit before we end the conversation. One is, what do you see as one of the biggest challenges facing the queer community right now? And then the second question is, what can straight allies do to be most helpful as the queer community is facing that challenge?

TW: Gotcha. Well, we’ve talked a lot about the progress that we’re making, and with that progress, there has been a significant backlash with hundreds of anti-LGBT bills being introduced all across the country. Sadly, it is transgender people who are bearing the brunt of these bills. They’re being scapegoated in a pretty aggressive manner. And when I see the hysteria that is generated around transgender people, I think of the French philosopher René Girard, who talks about this idea of scapegoating, which is a psychosocial mechanism that projects the anxiety of a society onto an individual, or in this case, a group of people. And it sanctions a form of communal violence or legislative violence to expel them from the society or from the town, et cetera.

And we are seeing this kind of moral panic around transgender people who are just trying to live their lives and trying to achieve their own hopes and dreams, and to be the source of so much focus from the legislature… It was such cruelty. It’s been really difficult for us to see and to actually respond to because it’s often irrational fears, and that’s very challenging. I worry about that tremendously. And we’re working on ways to try to figure out how to deactivate the amygdala for people who are fearful of transgender people, and hopefully we can encourage people to approach this very complicated issue with compassion and respecting the dignity and the rights of this community.

So, what can allies do? Well, I’m a huge proponent of allyship. We can’t do this work without you. Sometimes I will hear people say, “I don’t need allies, we’re going to do it on our own.” And I completely reject that, I think it’s all rubbish. We need allies at our side. I need you, Amy, at my side doing this work alongside me. I don’t want to do it alone, because it’s lonely. I want you to be at the party. And I want us all to remember, like we said earlier, that symbol of the civil rights movement of the black hand and the white hand together. I want to bring that back in all contexts. I think that the core of this issue, the core of allyship, truly, is friendship and a willingness to bear one another’s burdens. To be there when someone is in distress and to listen when hearts are breaking because of a piece of legislation or something that’s happened. And finally, just show up. Come to our events, our parades, our festivals and our galas, and enjoy the celebration, alright? Because we want you to march with us. And also, importantly, we want you to dance with us when we are celebrating. Because we need your anger in the face of injustice, but we also need your laughter to celebrate everything that’s beautiful. We have to have both. I don’t want to do it alone. I can’t do it alone. So, Amy, I need you by my side.

AA: Here I am!

TW: That’s what allyship is, is being together through difficult times and also joyful times.

AA: Yeah, that’s wonderful. Wonderful, wonderful. What I’d love to leave listeners with is some ways that we can show up and do work for people who are in Utah. I know there are some Utah specific organizations that I’d love you to talk about or at least mention. And you have an essay in a new book called The Book of Queer Mormon Joy. Speaking of joy, can you talk about some of these?

TW: Signature Books has a new anthology out, it’s full of several short stories. Some of our mutual friends, Stacey Harkey has a story in it, Eli Mccann has a foreword by Carolyn Pearson, and I have this really zany, tragic, funny story about how Elvis showed up for my mom’s funeral. But you’ll also see the seeds of all these conversations in that story. It’s about my own learning to accept my parents for who they were as I’m asking for their acceptance about who I am, and that’s an important journey. So that story is told in The Book of Queer Mormon Joy, it’s out now from Signature Books. And then in terms of local organizations if you want to get involved, you can go to equalityutah.org and you can see all of our programs. We have a giant gala on October 5th at the Eccles Theatre in downtown Salt Lake City, which is a big spectacle. It’s called the Allies Gala because we want allies to be there. And then there are other great organizations in Utah that we work closely with. I love the Encircle Houses and the work that they’re doing to elevate LGBT youth. There is the Utah AIDS Foundation Legacy Clinic, which is a clinic that helps complete healthcare for LGBT people in the state. And they are truly one of the great legacy organizations in Utah. And we encourage you to come and join us, there’s always some queer thing going on. Every little town has a Pride Festival now. Even in Short Creek, you know, I did my TV show in Short Creek for TLC, the former FLDS headquarter town, they have their own Pride celebration in Colorado City. So you can go march with them during their parades as well. There’s stuff happening all over the state and we would love you to be part of the celebration.

AA: Awesome. Well, Troy, I cannot thank you enough. Thank you for all the work that you’ve done. You are an inspiration to me, and thank you for this conversation!

TW: Thank you! Awesome.

We need your anger in the face of injustice,

but we also need your laughter to celebrate everything that’s beautiful.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!