“here we are, two people of color trying to navigate being queer and understand our identities.”

Today I’m thrilled to be joined by Chloe Agyin and Lakshan Lingam.

Chloe and Lakshan are members of a nonprofit organization called Encircle. Their mission is to bring together family and community to enable queer youth to thrive. Encircle provides services like support groups, educational and creative programs, and accessible mental health services in a safe and beautiful environment. In cities throughout Utah and other states where queer youth are most at risk. We’re so happy to feature this casual candid discussion between Chloe and Lakshan when they were together at the Encircle house in Salt Lake City, discussing identity, gender, orientation, and the power of representation.

Our Guests

Chloe Agyin

Chloe Agyin (they/them) is a queer multiracial social worker in Salt Lake City, Utah. At the moment they work as the Home Director of an LGBTQ+ Family and Youth Resource Center. Chloe has had the privilege of working with LGBTQ+ individuals in a variety of capacities, and they hope to continue this life-saving work. Chloe’s dream is to open up a queer bookstore in the South that is focused on amplifying voices of QBIPOC authors and provides a safe space for everyone that enters. When Chloe is not working, they enjoy being outside it in the sun exploring the beautiful landscape that is Utah.

Lakshan Lingam

Lakshan Lingam (he/they) is an undergraduate student pursing a degree in Gender Studies and Arts Technology at the University of Utah. As Executive Assistant, they help oversee the day-to-day administration and operation of Encircle. In their spare time, they enjoy searching for new music and spending time with their brother.

The Discussion

Chloe Agyin: Let’s talk about patriarchy, being queer, media representation. I think that’s a good place to start

Lakshan Lingam: I think that’s a really good place to start. I think a lot of our media for so long has been really influenced by patriarchal structure, and especially queer media always been built through the lens of men. And not only just men, but for folks who identify as heterosexual or straight. I think we are now entering an era even of better queer media, but when we were younger there wasn’t good queer media. It makes me think a lot about Ellen and that show and its audience, its projected audience and who it was supposed to really resonate with…how it wasn’t really made for the queer community, but it was really empowering at the time. For us. It’s a community. And it’s really cool seeing works being created by folks who are non-binary, transgender, and I think of all these really awesome shows that pull in those intersections of identity, and you can really see it reflected in the content.

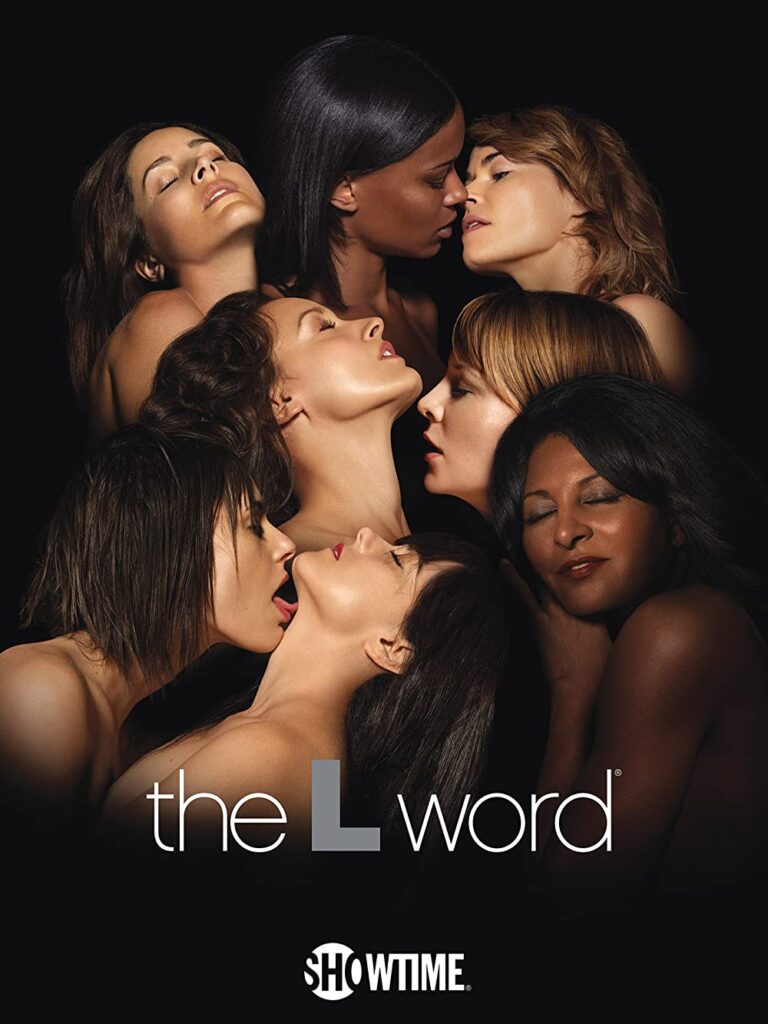

CA: I think for me, I guess the first example is like The L Word. It was so integral and what it did at the time of being a show that was specifically about dynamics within lesbians and things like that. It was such a huge turning point for a lot of people, and also still had really bad representation, and still had lots of problematic things in it. Right? It was very pivotal, very, very pivotal, but also still problematic in a lot of ways. And then seeing the new The L Word: Generation Q and seeing them taking all this feedback that had come from the original L Word to make changes and trying to include people with different identities and be respectful of those identities, it’s really important. And thinking back to how important that would have been for me as a baby, closeted queer person, right? Like, knowing that there are different ways to identify as being lesbian, there are lots of different ways to identify with my gender. And it’s not just I have to be a skinny, white person to be lesbian.

LL: That’s really cool. Seeing media evolve and change, I think a lot about the work that GLAAD is doing, has always been doing to be sure that accurate representation is being achieved in media. And it’s really cool seeing that change all that and seeing even who was reflected on the screen change – seeing more queer identities, more people of color, more ranges of identities and orientations and expression. That’s been really cool.

CA: Do you feel like media has affected the way that you’ve like, understood your sexuality and or gender identity?

LL: Yeah, I’m thinking about when I was younger. A lot of the media we were consuming when we were younger really contributed to normative socialization. We were being taught gender roles and how to be male, how to be female, what jobs, what careers made sense for what identity you were born as, what you were assigned at birth. And now we’re starting to see media that kind of challenges that a bit. And I’m seeing my brother who identifies as straight being exposed to so many different identities in media. It’s starting to become a lot more mainstream.

I think the impact it had on us as we were younger really influenced how we saw our own gender and how we saw our own futures as queer people. I remember when I was younger I never thought I would come out because of the way that I heard my community talking about being LGBTQ, saw media being portrayed about being LGBTQ. I think we’re starting, especially here in Encircle I hear all of our youth talking about their favorite shows, their favorite music, and so much of it is queer and it’s so…I don’t know how to describe it, but it’s I’m thinking of artists that I knew when I was younger, like David Bowie, where it was like, we knew he was queer. And that was awesome. It was really awesome seeing that representation, but it was never really overtly queer. But I think of like, growing up, Janelle Monae was one of my favorite artists. She was one of my favorite artists because it was one of my mom’s favorite artists. And she was on her first album and she dressed very masculine, androgynous. I thought that was so cool. I was so obsessed with everything she was creating. And then I think it was a couple albums later, where she started using same gender pronouns for people she was talking about in her songs. And I was like, ‘Whoa, Janelle might be queer!’ And I was like, ‘Hey, I can’t listen to Janelle anymore. That is not happening.’ And the year I came out was when she released Dirty Computer and that was really painful for me, not only as an album, but the motion picture that she released on YouTube was really cool. And I learned a lot from watching both of those and they are very intersectional in nature, and really shaped that. So I think now all our youth here at Encircle that are attending our programs, and here in the space, have access to a lot better representation. And that’s just the coolest thing in the world.

CA: Yeah. Can you explain to people how you identify? You kind of talked about how media has influenced the way you identify, but how do you identify?

LL: Yeah, so I identify as non-binary, and I use he/him and they/them pronouns.

How is your identity impacted by patriarchal structure in your life?

CA: Yeah. It’s like patriarchy does affect everything, because that’s the type of society that we live in, where men, boys are favored. And the characteristics of men and boys are favorite. I would say growing up in a family where I was the only daughter was really hard for me, because I could see lots of different ways in which my brothers were favored. Part of me wanted to be like them, because their attributes, their characteristics, they literally could just exist and be favored by my parents, favored by society, right? Where I felt like I was always playing catch up that no matter what I did, it wasn’t enough. I wasn’t feminine enough, you know? And I feel like that was really hard for me because, as a queer person, it’s like this kind of coming to an understanding that I could be a female identified person, but also not be super feminine as well.

I remember when I was in sixth grade I loved shopping in the boys section. Like it was my favorite thing. I loved wearing boys clothes and everything like that. And we went shopping with one of my aunts one time, and I was like, ‘Oh, can we like, go check out the boys section, because I want to shop there, because that’s what I feel comfortable in.’ And she shot me down, was like, ‘No, girls do not shop in the boys section, you are going to become a woman one day, and no man is going to want you because of the way you dress.’ I feel like that stuck with me for such a long time, and was always in my head: I have to be feminine, I have to present a specific way so that I would be attractive to men. But I wasn’t even attracted to men. Like that’s not what I wanted. But it was like, ingrained in me that like, this is how I had to present and I felt like the expectation and the expectation. I felt like for a really long time I was trying to be this person that I wasn’t. I was trying to be so feminine, but I didn’t know how and I felt awkward. And I felt uncomfortable. And because of that I felt I had to hide so many parts of myself, because if people saw who I really was, people saw the way I really wanted to dress, characteristics that I want to actually show people…I would be rejected, right? Because of this idea that my identity has to center around the male gaze. It doesn’t, and it wasn’t until I came out when I was 23 that I realized that that’s not what I wanted, or who I was. And then it was the opposite, rejecting all of that and this idea of being lesbian…I remember just being lesbian is so tied up in patriarchy, which is like weird because like lesbians…there are no men in the identity of being lesbian. But it is still so tied up in this idea of being centered around men and the way it’s portrayed in media, talked about, lesbians have existed in media for men. So for me to identify strongly as lesbian, it felt like I had to reject all of my femininity, because I didn’t want to be seen as someone who was doing it for the male gaze again. It was this really weird and interesting thing of how do I accept myself as a feminine being, and also embrace this masculinity that I have in me, and not feeling like I was doing it because I wanted attention from men? Does that make sense?

….that stuck with me for such a long time, and was always in my head: I have to be feminine, I have to present a specific way so that I would be attractive to men. But I wasn’t even attracted to men.

LL: That totally makes sense. And actually, what you’re saying reminded me of a conversation we had with Stacey Harkey here at Encircle. Stacy was reflecting on his experience at BYU (Brigham Young University), and it was so funny because I remembered him talking a little bit about being afraid and really being conscious of the way he walked and the way he spoke and the way he just moved throughout campus. And then reminded me, and it was kind of relating to your story of being in the store with your aunt, It reminded me for the first time in a long time because I’ve been in this safe space surrounded by queer people, and being in a space where I’m really welcomed for being my authentic self. It reminded me that I used to have those fears. That I used to be so wrapped up in expressing my masculinity so overtly so I wouldn’t be perceived as queer. And that experience, your experience in the store, because for your aunt it’s such a small thing to say, but it’s so damaging to us and our identities. And it’s so influenced by patriarchal structure. My non-binary identity is very influenced by wanting to escape that expectation of me in a patriarchal structure. I grew up in a very patriarchal home. My family is first generation American, my family’s from Sri Lanka, my parents are an arranged marriage. The way women are treated in a Hindu culture and in Sri Lankan culture isn’t…it just didn’t sit right with me, truthfully. And my non-binary identity was primarily motivated by me not loving the stereotypes or the expectations that, being male, were assigned to me.

I really like using they/them pronouns because I feel like it’s a way for me to really be myself and be authentic and fill the space that I need. I remember when I first came out, I felt the need to just be very masculine, and continue to dress very masculine. And then there was a period of time where I was like, okay, like, I was really assessing my bias. And hey, I really have to start embracing parts of femininity, and really being vulnerable, and really being present with people. I really wanted to do that. I tried finding a balance between the two, and it wasn’t really working for me because I was really performing both. And that was really hard for me. So I found myself now in a space where I dress how I want and do what I want. I am me. And I think that’s a world where we should all strive to be more.

So yeah, I think these structures are so ingrained in our culture, and our media, and all aspects are our lives. It’s inhibiting us from being ourselves for a very young age. It’s really cool seeing the opportunity that every year it gets a little better. I feel like the conversations among our youth have changed at Encircle even. I feel like when I first attended Encircle out here, a lot of youth would still have these conversations in friendship circles. They’re talking about their identities, and the hardships they’re facing at school and at work and all the spaces there are. Because it’s definitely not ideal. We’re definitely not there; we haven’t arrived. But it is cool seeing conversations, shifts, sometimes. Just conversations among kids, because all of our youth can actually talk about their favorite TV shows that happen to have queer folks in them, and their music.

CA: We’ve like talked a lot about like, gender identity and patriarchy, but what about your sexuality and how that ties into patriarchy?

LL: I identify as gay, and I remember when I was first dating I really struggled trying to figure out…how do I date? Like, how do I date as a gay man? And it’s so funny thinking about I, who come from a very patriarchal background, and my partner who does as well trying to figure out how to be vulnerable with each other and really figure out how to have a relationship with each other. It was hard because we are taught to be very closed off. I grew up in a very different family structure than my partner did. And I don’t know…it’s just really interesting and it can be really complex, but I think we can definitely get there. And I think it takes a lot of self-reflection and assessment of your biases and how you’re brought up to really understand how to navigate that.

CA: Do you feel like you’re in a place where you’re vulnerable now?

LL: I mean, there’s always work to do. There’s always times and spaces where I’m like, ‘Hey, this feeling I’m having right now or navigating this part of our relationship is influenced by how I was brought up, and how I perceived being the male in a relationship would look like.’ There’s always going to be that, there’s always gonna be a back and forth, but I think we’re in a really good place where I’m really vulnerable. It’s hard for me to be…being queer men, it’s hard. Understanding how to navigate that relationship is hard, because any queer relationship is hard. I can’t imagine what…like for you, identifying as lesbian and dating someone who identifies as female, you still feel the effects of the patriarchy in your relationship. And I think all queer relationships will always feel that kind of pressure.

I found myself now in a space where I dress how I want and do what I want. I am me. And I think that’s a world where we should all strive to be more.

CA: Yeah, that reminds me of gender roles, right? Gender roles are so clear in relationships. And just like kind of what you’re saying about the patriarchy influencing that. How many times do I get asked, ‘Who’s the man and who’s the woman in the relationship?’ Obviously, based on this idea that there has to be a man in a relationship, and we’re just two humans trying to figure out what we both like, and then navigating our relationship based off of that.

I always tell people that like, vacuuming isn’t a gendered thing, right?

LL: It’s just something everyone should do!

CA: It isn’t a gendered thing. It’s just things that we like and dislike, and this idea that we have to be forced into these roles. I think that’s my favorite thing about being in a queer relationship, is that I can do what I love, my partner can do what she loves. And we meet somewhere in the middle, right? Like, I love cleaning. It was just my thing that makes me so happy; I will vacuum all day long. My partner hates it. But does that make me the woman and her the man? No, my partner loves to host people, and I hate it. Does that make her the woman and be the man? No, that just makes us us. It’s so freeing. Once you get to this point of understanding that relationships, whether it’s queer relationships or straight relationships, we should be complementing each other in these ways, and we shouldn’t be proscribing gender identities, gender roles onto stupid things like vacuuming, right?

LL: Totally. I love the way you said that because it makes me think about the little things that we do, right? I like to think of it as two people navigating life with each other. And you’re always figuring out how to do that with another person. It doesn’t matter really how you identify or who you’re with or what their sexual orientations are. We’re just partners. And we’re figuring that out.

CA: Yeah, for sure. I think that also like ties into sex. Even the idea of like queer sex. It’s the idea and understanding that we have of sexual relationships as being between a man and a woman, right? Again, as a lesbian, I get often asked, how does sex work? How do you do that? Like, if there’s no penis, and there’s just two vaginas? How do you how do you make that work? There’s just this idea that there has to be a man in everything for it to be considered valid, for relationships to be considered valid. Like for a sexual relationship to be valid there has to be a penis, and it has to be a vagina, and there’s so many things outside of that.

How many times do I get asked, ‘Who’s the man and who’s the woman in the relationship?’ Obviously, based on this idea that there has to be a man in a relationship, and we’re just two humans…

LL: Sex isn’t the only part of relationship, right? I feel like queer relationships are definitely hyper sexualized, and that’s really unfortunate because no one should feel comfortable asking someone else about their sex life, especially a queer relationship. It’s private. And that’s part of a relationship. But I agree. I remember when I was first coming out, I was like, ‘I don’t know how to do anything.’ There weren’t very good resources, etc… Sex Education in Utah specifically, isn’t where it needs to be. I am in the school for cultural and social transformation at the University of Utah; we spent a lot of time talking about what sex education would look like if it was queer friendly, or how vital that would be for the queer folks that are going through our sex education program.

CA: Talk more about that. How would it be different?

LL: I think queer people would feel a lot more affirmed in their identities, and it wouldn’t feel othered. Because we would see more of it in not only, like we were talking about media earlier, but in curriculum, and it wouldn’t be so much like…you being queer is something we don’t talk about. And it’s also like, being queer is not a phase, right? And I feel like not having queer relationships in any kind of curriculum, whether it be history, science, education, anything indicates that you’re other and that you don’t matter in our society.

CA: It’s kind of like what you are and how you identify is wrong. That it’s something we don’t talk about, like we don’t talk about queer people because it is wrong, is how it comes across.

LL: Totally. And that’s so sad. It’s heartbreaking. And so funny, because like, I think that when I was in middle school and I’d recognize things like that subconsciously, I’d recognize the omission of queer relationships or like…we never even talked about it. I’d recognize that, but it was very subconscious in the sense of I was just trying to get through middle school, through high school, but I also never really thought I would be in a space where I was affirmed in my identity and could come out and thrive as a queer individual. It’s funny because people always ask, when did that switch for you? It’s funny because it was at Encircle I remember going to an event, we used to have a program we called Tools to Thrive. And I saw Paul Tu speaking at Tools to Thrive, who’s really awesome, and seeing another queer person when I felt like I was the only person in Utah County talk about what they’ve done in life, all the amazing things they’ve achieved, was really life changing for me. I think the structures we have (and we’re getting so much better as we go) just didn’t allow for discussion of queer icons and heroes and our history.

CA: Yeah, yeah. Again, tying this back to the patriarchy. Because men don’t think that representation for queer people is important. It doesn’t happen a lot. Like you’re saying, it’s better now but definitely not where we want to be. I just feel like time after time I hear so many stories about people who are like, ‘Because I saw a queer person who looks like me, who acts like me, who wants the same things that I want. That’s how I knew that my identity was okay.’ You know, just that importance of representation and decentering this idea of what men think is what it should be in our society. Because there are so many other identities. And being a man, and even within that there are lots of other identities as well, right? The intersectionality of being a man and being gay or being a man and being trans, being a man and being a person of color…there’s some so much complexity within that in and of itself. Yeah, but it always doesn’t feel like that…

LL: Totally. And again, patriarchy’s impact is not only on women or on men. It’s on everyone. It’s on all of us as a society. And I think a lot of times when people hear the word patriarchy, they attach it directly to toxic masculinity, and they think about its impact directly on women, but it really does impact men as well. I don’t know why this is what I’m thinking of right now, but the Gillette commercial that featured a trans man and a dad teaching his son after transitioning how to shave, and the backlash we got from men seeing the Gillette commercial (having used Gillette forever) being so upset. I remember thinking how you have been brought up, how has your life experience taught you that that’s not okay? When really we all should just be comfortable being ourselves. And I know that commercial is so cool, the coolest thing in the world.

You know, we haven’t spoken much about patriarchy and homophobia, and how they’re structures that hold each other up. I think patriarchal structure and the way we teach patriarchy in our society, definitely influences and empowers homophobia, not only among men, but women and all those in our communities. And it can be really damaging for queer folks who already feel othered in our communities.

CA: Can you talk about that? I know that we’ve talked previously about how you’ve had some internalized homophobia and you’ve worked really hard to overcome that.

LL: Yeah, I don’t think there’s ever a point where any queer person fully overcomes it…we are always going to be impacted by our lived experiences, and our lived experiences have always been shaped by a patriarchy and homophobia. It’s just the truth. I think back to when I first was coming out, like I truly did not believe that coming out would be….now coming out has been the best thing that I’d ever done. I live my most authentic life and started meeting the best people. I’m just so happy with where I’m at and how my identity is expressed by me. But I think when I first came out that internalized homophobia was really great. I didn’t think I could thrive as an LGBTQ person. And coming out to my family like that was truly made clear that they didn’t think I would either. And it takes a lot of really like self-reflection and understanding how your lived experiences may have worked to teach you that your identity isn’t okay. But you’ll find a space. It’s so hard.

Anytime I’m like ‘I grew up in Provo, Utah.’ People were like, ‘Oh, that’s so hard’. And I’m like, it’s funny because at the time, it wasn’t, I was good. And I still really love Provo. And I think like some of the best folks I know live in Provo, and it’s such a good space to be in. It can be really welcoming. I’ve seen it progress a lot in the years since I’ve come out and, you know, moved from Utah to Salt Lake City.

CA: Can you tell people about Provo, Utah? Why that’s so shocking for people?

LL: Yeah, I think in Provo the predominant religion is LDS. And I think there are a lot of negative attitudes and hostile attitudes towards LGBTQ identity. That’s not something that was super talked about when I was younger. I’ve seen a lot of really cool organizers in Provo, other than Encircle, creating and working to create a better space in Provo, Utah. And that’s been really cool. I think in small towns across the nation, there were people who feel like they’re the only LGBTQ person in the world. And they’re like…it’s never talked about, they never seen media, and there’s just a whole generation of queer folks that feel like they don’t belong. And that contributes to our crazy rates of suicidality among LGBTQ youth in the United States. And it’s really sad, as largely created by this structure of patriarchy. That’s just all encompassing.

I saw a queer person who looks like me, who acts like me, who wants the same things that I want. That’s how I knew that my identity was okay.

CA: I think pointing out that this is an experience that lots of people have across the United States, right? Who come from small towns where it does feel like you’re the only one because 1) no one talks about it or 2) if people do talk about it, they’re shamed for it. So you’re like…I don’t want to I don’t want to be that. I don’t want to be the person who’s shamed. And it’s safer for me if I just don’t, because there’s no one else here who can relate to my experience. And I feel like the same way to you. So like, I went to BYU, which is in Provo, Utah. And when I was coming out (I think we came out around the same time) I think around 2017…

LL: I’m trying to remember which album John Legend had released, but around that, yeah.

CA: So it’s around 2017 and here we are, two people of color trying to navigate being queer and understanding our identities, but also feeling like, there wasn’t anyone else out there who related to my experience. And just how important it is, like, again, visibility is so important. And having this internalized homophobia of ‘being gay is bad’. Like, even after like coming out and this idea that ‘Oh, it’s okay for them to be gay. But it’s not okay for me.’

LL: Totally. That’s how I felt, too. I would see queer relationships and think ‘That is the coolest thing, but I can never do that.’

CA: There’s a study that shows that most queer people know that they’re queer by the age of 12, but don’t come out until 22. They’re 22, which is 10 whole years of this idea of being gay is bad being really just sitting with it by yourself. Like being gender diverse is bad. We don’t really think about that, we might say things off handedly and we might treat people a specific way and not understand the impact that has on people around us. Right? How many people do I meet that are like, ‘I don’t know, a gay person’, or ‘I don’t know a trans person.’ It’s like, ‘No, you do, you’re just probably not safe enough for them to come out to.’

LL: Right. And if you are noticing that you don’t have queer people in your life, you have to make space you have to really sit back and sit with yourself and figure out where your biases and assumptions have led you. I think it’s really cool because here at Encircle will we see volunteers coming all the time and they were like ‘I was missing any ties to the LGBTQ community.’ And they come to Encircle and they learn so much. They become really true advocates and allies for the queer community. Then it’s so funny because over the last few years, I’ve seen volunteers be like, ‘And now my kid has come out or my neighbor came out to me and I’m learning how to be a safe space.’ That’s the coolest thing.

CA: To speak to that, I feel like because I have conversations with so many parents who are like, ‘I love the LGBTQ community and I’m so shocked that my kid would be afraid to come up to me.’ And it’s like, ‘Yes, while you may be supportive of LGBTQ community, it’s those little things that we say, that we believe, the religions that were tied to…what are all of those things saying? What are the people around us saying that we’re not speaking up against it?’ That is teaching your kid that these ideas, these beliefs can be upheld. And that’s why lots of kids are afraid to come out to their parents. Because while you may be like, Oh, rah, rah, I have all these queer friends, but you’re saying all these homophobic things behind their backs or, you know, you are part of a religion that preaches against gay people, gender diverse people, right? Like, what’s not a safe space that someone wants to come up to?

LL: I’ve also struggled with, like, I hear parents sometimes say the same thing where they’re like, ‘I tried all I can to be a safe space’, and it breaks my heart. Because I’m like, some of these parents, I know, they’ve done all they can to be a safe space, they’ve tried so hard to create a safe space, but even if they’re perfect, our society as a whole isn’t. So our youth are going to be hearing things about queer relationships in school, at church, and all of the different structures and systems in their lives. And even if their family is fully accepting and trying so hard to build a space where they could come out safely, the world is still teaching them that their core identity is wrong. And that can be really hard to, because I know a million parents that have the best intentions. It’s hard. It’s definitely hard.

Chloe, what do you think a good takeaway from our conversation would be for all of our listeners today?

CA: I think for me, the biggest takeaway would be to identify your biases. That would be the first step, right? What are your biases? Even if you are an ally, even if you are queer, we all have these things that we’ve grown up with, like Lakshan has been saying, right? We all have these biases within us. And that’s okay. It just time to like for us to look at them; what are they? And how can I change them? And being really, really intentional about changing and about seeing people the way that they want to be seen.

Words are so freeing, but at the same time, they can be so limiting. Lakshan and I both use they/them pronouns, but what that means to both of us is so different. For a while I was identifying as non-binary, and Lakshan identifies as non binary, but the way that we relate to that word, non-binary is so different. And I would say that my biggest takeaway is, yeah, be curious, confirm your biases, and really try to see people the way that they want to be seen, because we don’t do that enough. And using language, again, is so freeing, and also so limiting. So remember that.

Do you want to speak to that a little bit?

LL: That was so good. And I think you’re absolutely right, language means so much, language is so important. It feels like such a small thing and the things you say can feel really small, but intention over impact, right? Really understanding and sitting with that. I’m speaking directly about the queer community right now, but know that like no labels, we might use the terms we identify with really vary person to person.

we are always going to be impacted by our lived experiences

and our lived experiences have always been shaped by a patriarchy and homophobia

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!