“…this is how it happens, I’m watching patriarchy play out in front of me right now”

As women and our allies continue to share knowledge, resources, and take action to dismantle oppressive structures, the progress we make is being met by oppositional movements. Here in America, the MRA Movement (or Men’s Rights Activism) continues to expand its reach and intensify its rhetoric, with prominent MRA leader Matt Forney going so far as to say “Women should be terrorized by their men; it’s the only thing that makes them behave better than chimps.” Meanwhile, crimes targeting women and girls have only continued to increase world-wide. The picture this paints seems clear – some men are aggressively pushing back to protect a repressive status quo and when women voice frustrations with the situation or – yet it is not uncommon to hear cultural and political leaders continuing to claim, as Sen. Josh Hawley did only a few months ago, that “men are under attack.” And believe it or not, I’m going to agree with Senator Hawley on that point…

Men are under attack, but not from feminists and others fighting for equality; men are under attack from the very same patriarchal institutions which diminish the rest of us. They are taught that there is a small box of acceptability that they must fit into or be shamed (or worse). Most damaging of all, men continue to be taught not to speak up against other men in situations of injustice, not to upset the normativity of a repressive system which ultimately serves none of us.

But if all of us work together, we have the collective power to put a stop to these systems and build a world that works for people of all genders. And that’s why today I’m excited to be bringing men’s voices to the table – men who are ready to pull away the wool patriarchy has draped over their eyes and speak out about injustices they’ve observed and even participated in. We’re so grateful to share their courageous voices with you today.

Andy Dunn, who takes us on a tour of moments when he’s recognized the ways patriarchy has shaped his life.

Ian McAllister who explores the role of patriarchy in Hollywood productions, professional marketing, Greek life, and more.

Our Guests

Andy Dunn

Andy Dunn (he/him) co-founded menswear brand Bonobos and served as CEO until its 2017 acquisition by Walmart. As an investor, he has backed more than eighty startups, including Warby Parker, Coinbase, Away, Glossier, Real, Parade, SeatGeek and Alula. His memoir, Burn Rate: Launching a Startup and Losing My Mind, explores the intersection of entrepreneurship and mental illness.

Ian McAllister

Ian McAllister (he/him) is a father and small business owner in Portland, Oregon. When he’s not chasing his two year old daughter around you can usually find him at a farmers market, on the ski slopes, paddling the rivers of the Pacific North West, or cheering at a college football game.

PART ONE.

Swimming in Privilege: Waking Up to Male Entitlement

Andy Dunn

David Foster Wallace’s commencement speech at Kenyon College from 2005 begins:

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

These words ring particularly true today. As a man in a #TimesUp #MeToo #SayHerName world, it’s not enough to pay lip service for a second and move on.

The real work begins with acknowledging that I’ve been swimming in the water of male privilege every minute of my life.

I wish I could tell you I saw the water on my own.

I didn’t.

My wife Manuela showed it to me, like a revelation, step by step.

Even in writing this essay, she lit the way. Initially I felt paralyzed. I didn’t know what to write. I don’t feel I’m better than any man out there, or that I have anything to teach, and the more I learn about myself, the less comfortable I feel saying anything at all. So I defaulted to what felt safe— a celebration of the powerful women in my life, a restating of facts everyone already knows, and a toothless, non-specific, uninspiring call to action.

That’s when Manuela intervened.

“This whole essay I’m waiting for you to stop telling me what I already know and to start to do the work. The most helpful thing you can do for men is show them what you are wrestling with.”

So here goes.

Here are seventeen examples out of a hundred I could write about where I recognized my own male privilege in action, and it excludes the thousands I cannot choose from because I didn’t (or still don’t) even know I was (am) swimming in water.

- It starts small. My wife and I are riding in the car. She does a mental calculation. I compliment her on it, impressed by how fast she ran the numbers. “Wow, you’re good at math,” I say with a smile. I expect gratitude for the compliment. Instead, she stares daggers. “Why are you surprised? Do you assume that as a woman I’m not good at math? Would you have said that to a man?” The conversation goes dark. It takes me a few days to realize that my hurt at having a compliment thrown back at me is far eclipsed by the unconscious bias I showed in saying what I did.

- I’m out to dinner with an entrepreneur. She has twins. Somehow the conversation turns to parenting. Being without children, I expertly opine that women are fundamentally better at taking care of young children than men. I cite empathy and nurturing ability as women’s advantages. I suspect as a mom that she will agree. Instead the music of our conversation screeches to a halt. She informs me that this is precisely the kind of thinking that enables men, who are every bit as capable, to cop out of doing the real work of equal parenting. Blinding light.

- After a fireside chat at work with an industry leading executive, I feel good. She brought good energy; the crowd was into it. In talking afterwards to a woman in attendance, to my surprise and alarm she expresses disappointment, pointing out that the question I asked the exec about how she juggles being a parent and a brand president I would never have asked of a man. At first it feels unfair, as I know I’ve asked men the same question. Then I think about it, and I realize that the way I asked the question was different. It wasn’t a “tell us about your kids,” which I normally ask the men, it was a “tell us how you juggle it all,” which implies women should have more to juggle than men, and which is only true if we have lower expectations of what men should be doing in the first place.

- We are debating how to establish maternity and paternity policies at work. Someone points out that in Sweden parents get paid 480 days of parental leave when a child is born or adopted, and that it’s equal for both men and women as the expectation is that both parents will contribute equally. My head explodes. We are nowhere close in this country.

- At a meeting, four men are dominating the conversation. A few of the women in the group try to get in, but are quickly cut off or interrupted. I don’t know which men in the room are seeing the pattern. I start to feel like the only one. My anger rises. Losing my temper, I inelegantly jump in to point it out. The room gets quiet, and I realize that maybe I’m getting emotional because I know deep down that I have spent the majority of my professional career doing the exact same thing.

- Our board is all men. I try to recruit a couple female board members but fail. One woman joins. Soon she resigns. Finally a woman comes on the board and stays. It takes two years from goal to outcome. After all that, it still dismays me to know that with six men and only one woman on our board, we remain below an already low average.

- I learn about the terms manspreading and mansplaining. I had no concrete concept of what either of those things were until they became words that reached my ears. Even after being educated on both, I catch myself relapsing. Everywhere I look I start to notice men cutting women off as they walk, entitled to the space in front of them. It becomes dizzying to think that I only see this because I’m paying attention for the first time.

- In a conversation with a male executive, he tells me that he doesn’t hire women because ‘it’s not worth the trouble.’ I mentally blacklist him. This was fifteen years ago and I was working in another country. What I didn’t do is rattle the cage that he should be fired or resign from the project in protest.

- #MeToo unfolds. It does not come as a surprise. I’m in Hollywood the week the movement is gathering steam, and powerful men around me are feigning ignorance. The faux surprise is disgusting. I begin to take inventory of my life, and I feel complicit. I’ve been in thousands of conversations dripping with misogyny. I’ve initiated many of those conversations myself. From my fraternity roots to my bachelor days in New York, I know I have not always shown up in ways that I am proud of.

- I comb over my bookshelves: my estimate is that 80 percent of what I have read in my life was written by men. I start paying attention to what my wife reads, what she listens to, the culture she absorbs. I start thinking about all the books I haven’t read in my life, of all the perspectives of women out there which I have not explored. Inspired by my wife’s voracious reading of them on our honeymoon, I dig in to Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. They reawaken me to the wonders of women’s fiction, and remind me that the imagining the lives of women requires learning not just from the women who we know in real life, but also the women, whether real or fictional, who we don’t.

- A man who I am interviewing orders a red wine. I make fun of him later, with other men, for not ordering a cocktail or a beer. Later, he cries in a one-on-one meeting with me. The mockery sidebars continue. It’s only now in looking back that I see sexism is not just oppressing women, but in the very idea that there are “male” and “female” behaviors, and the multilayered problem of oppressing not just women, but also the emerging “women-ness” of men.

- I start thinking about language. History = his story. You guys = you people. Mankind = just men. Once you start to see it, male privilege is embedded not just in our systems of thought, but in all the language we use. My wife maintains the word bitch should go the way of the n-word. Women can use it, at their discretion, but not men. It carries with it centuries of repression.

- A man I know tells me he won’t have dinner with his women colleagues, but will with the men he works with. I take stock of the staggeringly disproportionate amount of time I’ve spent in my career socializing with men versus women. I start to wonder all the ways that might affect advancement and career trajectory, how I might have both benefited from it in my career and fostered unfairness once I became a leader.

- At a business dinner, there are four, small circular tables and about twenty people. Half of the attendees are women. I am assigned a seat at a table filled only with the most senior ranking men present. Many of the women who worked hardest on the project are seated at their own table, together. A joke is made, in passing, by one of the men there about it being the “kids’ table.” It was awkward, and it begged a painfully obvious and symbolic question: how are women supposed to ascend if they don’t have a seat at the table with the men in power? The right move for me as the CEO of the client company was to intervene and juggle the seating on the spot. Everyone would have responded, and the humiliation would have shifted from the women who were excluded and to the men who made the seating arrangement. Instead I just sat there, too much of a coward and too slow on my feet to convert awareness into action.

- Before we got married, my wife and I spent six months in therapy to address our problems. One of them was all mine — which is the issue of me steamrolling her conversationally with extroverted enthusiasm, and not creating the empty spaces for her, a self-proclaimed and proud introvert, to be able to get in. I adjust course and try to shut up. Slowly, things get better at home. It dawns on me that I had been doing the same thing in my professional life for years. I start spending most of meetings silent. I start inviting people who are quiet at the table what they think. I start to see my core role as facilitating a vibrant discussion, which requires equal contributions from others while I as the leader spend most of the time listening.

- My team asks me to interview a transgender athlete. As our conversation unfolds, I see the ways in which I still am limited to a heteronormative worldview. My definition of gender expands beyond just two genders. I’ve been saying LGBTQ for years, to fit in, and had given very little thought to either T or Q.

- My wife and I are in an argument. At some point I bring up that I pay more of the rent. She holds back tears, and reminds me that we had agreed to the way we were paying the bills, including paying for utilities and groceries and as big a chunk of the rent as she could afford. She went on that she brings a lot to our relationship too, not all of which can be valued in dollars and cents, and that in 2015 women in the U.S. were paid, on average, 83 percent of what their male counterparts received annually, (This compounds over a woman’s lifetime, and that it’s worse yet for African-American and Latina women.) I am reminded of the scene in Fences, where Denzel Washington bellows at his son about putting a roof over his head. I think of the eons of men who have used economic power unfairly secured to lord it over the women in their lives. I am reminded of all the ways men wield power, physically or financially or sexually or otherwise, to undermine the humanity of the women they love and who love them. Later it is me that will be crying.

I am not a wise old fish with the answers. But I’m not a young fish anymore, either.

I know that the work begins with the listening, to truly hearing the talented women around me. I know I should stop questioning their realities and instead acknowledge their challenges. I know that then I must partner with them to be a force for change, and that this needs to happen in all spheres, personal, professional, and civic.

I know that this effort also demands serious conversations between men, conversations which we know are not happening, certainly not enough. It means not being afraid of calling men on the carpet, of calling myself on the carpet, that when I see the worst of me in them, even if it exposes my fundamental underlying hypocrisy, to call it out, and to in return not just ask that they do the same for me, but to demand it.

It’s time for all of us fish to wake up.

PART TWO.

The Gatekeepers

Ian McAllister

I’m a white cisgender man, patriarchy absolutely exists, and I am a huge fan of this podcast. I’m so excited to contribute to this conversation about patriarchy because I believe it is some of the most important work that we can be doing right now. I believe it is crucial that people like me join this conversation, ready to listen, ready to learn, and ready to speak vulnerably. I feel like writing this essay has been a microcosm of what it means to do this work on a larger scale. I’m driven to explore these ideas by a strong sense of what is right, and a strong feeling in my gut that this is something I want to move towards. However, putting my finger on exactly what my story is in this space has definitely been challenging. The space that I feel I can speak most authentically from is the story of how patriarchy and power structures can be normalized. In my story, I can see how this heaped on both a personal scale, but also on a larger cultural canvas.

My story’s about how my passion for big ideas carried me to Hollywood and home again, and what I’ve learned about bravery and feeling alive along the way.

First off, I think Amy is an incredible host — I am so thankful that she has made so many of these essential texts and historic figures accessible. I consider myself a relatively well-informed and progressively-minded individual, but before listening to this podcast I would have described feminism as a contemporary movement. Breaking Down Patriarchy has helped me realize how wrong I was in that assumption. I now have a better understanding of how people — like Olympe de Gouges with The Declaration of the Rights of Women or Judith Sergeant Murray with On The Equality of the Sexes — have been talking about the problems of patriarchal power structures for centuries. How each generation has had to reinvent the wheel and come to many of the same conclusions, more or less in a vacuum. I think it’s difficult to come to that understanding and not to feel furious about it. To recognize that these forces for change have been out there forever, and they’re constantly impeded by countervailing forces. I can’t help but imagine how the entire world would be a better place if more people knew these stories.

I’m particularly oriented around the value of stories because they played a significant role in my life for a good chunk of my career. I was fortunate enough to attend and graduate from the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts. For an ambitious and creative twenty-year-old it was one of the most exceptional experiences I could have dreamed of. Going to school to make movies and to work with other highly motivated peers in a field with the potential for global impact was so exciting. Looking back on my story, USC was definitely an inflection point on my personal journey with power structures and my relationship with them in my own life.

…these forces for change have been out there forever, and they’re constantly impeded by countervailing forces. I can’t help but imagine how the entire world would be a better place if more people knew these stories.

At USC I joined a fraternity. Even at the time I remember acknowledging a discomfort with the Greek system around what I described to myself as ‘hyper gender roles’. Much more so than what I experienced in High School, it felt as though gender stereotypes were on full display. This is a moment where I feel I need to go off script because I really struggled to capture my feelings around this space in words. I believe that many awful awful things have happened in the Greek system around misogyny and patriarchy. That being said, I also feel incredibly thankful that my experience was not that extreme. While I am certain that I have not fully unpacked all of my experiences during that time in my life — and there probably are areas that I need to explore more fully — where I am at in my journey right now is this understanding.

I vividly remember gender roles smacking me in the face during a weekend volleyball tournament that was being hosted at my fraternity by one of the sororities. Teams from several other fraternities were playing in our backyard, many people were drinking, and someone from another fraternity didn’t want to wait in line for the porta-potty and instead peed on our parking lot wall. This sent one of my fraternity brothers through the roof. I remember him running into our house, completely amped up, yelling how we’d been disrespected and trying to recruit a group of guys to go ‘kick their asses’. Standing in that moment, I remember thinking to myself: this is how wars start. I felt so incredibly uncomfortable, but I didn’t say anything. I, and many others, normalized his behavior. I remember comforting myself with the personal coaching I’ve done so often in my life. “You’re here to learn,” I told myself.” Learn about these systems so you can change them from the inside.” I was scared. I didn’t want to speak up. I wish I had had a stronger voice then, but I didn’t.

My read of the situation now is that that sort of honor-defending behavior is absolutely a product of patriarchal teaching. Even at the time, it felt to me as though this fraternity brother of mine was playing into a script that he had learned was his role to play in life. That was the first time I had ever seen anything like that. I was raised in a space that valued compassion and tolerance and what I saw in that moment was not that. And that was not the last time that I experienced something that made me uncomfortable like that did.

At that time in my life, I was consistently living out, or rather, I justified to myself that I was living out an ‘immigrant story’ (which sounds so strange when I say it now). But I felt out of place. I was going to school with so many kids that I saw as so much more incredibly wealthy than I was, with so much more access to opportunity than I had. In hindsight, I also had a fair amount of privilege and access to opportunity, but I felt like I was in a world where I could easily have to pack my bags and go home. It’s such a Hollywood cliché of people who come to town with big ideas and don’t succeed, and end up going back home with their tail between their legs. And now, ten or fifteen years afterwards recording this for a podcast, I feel embarrassed that that was what I was thinking, but it definitely is what I was thinking and feeling at the time. I did not feel as though I could have a voice at that time and speak up for things that I didn’t agree with…unless they fit very conveniently into socially acceptable ideas of what I should be fighting for. Isn’t that what patriarchy is? A prescription for how we should be acting — how a man should act, how a woman should act to be culturally acceptable?

I think of that as the beginning of my journey.

I remember thinking to myself: this is how wars start. I felt so incredibly uncomfortable, but I didn’t say anything. I, and many others, normalized his behavior.

Not long after graduation I found myself in the world of talent representation at one of the largest talent agencies in Hollywood. I read hundreds, if not thousands of scripts, and tried to pick winning stories and winning storytellers. I found some success in the space, sold some projects, and represented some writers.

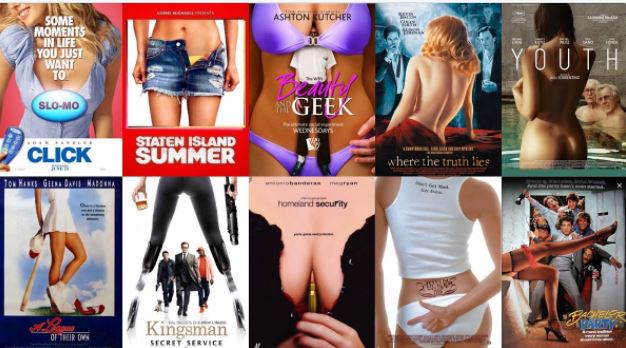

For most of my twenties I was trying to be a motion picture literary agent. At that time, our job was about analyzing what movies were made, how they performed, and then trying to reverse engineer the successful ones. We’d pitch projects as “this is successful movie A, meets successful movie B”. We’d try to articulate how “this movie would be perfect to make because couple X in Kansas City wants to go watch something on date night with a little action for him and a little romance for her.” Basically, I was paid to make huge (often gender-based) assumptions about our audiences and why certain movies performed the way they did. Some of those assumptions were “fan boys are the best audience”, or “women don’t go see movies opening weekend, unless their boyfriend drags them along”. I remember how shocked people were when Bridesmaids came out and completely blew away the assumption that an all female cast couldn’t launch a blockbuster comedy.

Hollywood certainly is not the only industry to profile their customers. Any good marketer tries to understand who they’re selling to and the best ways to talk to that audience. With the products that Hollywood sells, the chicken and egg situation of both reflecting and creating culture can be incredibly problematic. Under the guise of “knowing what the audience wants” so often the reality that Hollywood reflects back tends to fall back on traditional social gender roles and patriarchal power structures. Of course I have to caveat here because I have been out of the entertainment industry for a number of years so everything could have changed, but I’m guessing it has not. I think that the congressional probe that Facebook has been under recently regarding the responsibility of social media platforms to consider the wellbeing of their customers is in the same vein as Hollywood’s responsibility to its consumers. They have such an incredible platform and it can be used in ways that make society a better place…or not.

Something I remember from film school which falls more in the positive category is how cable television arrived in rural India in the 90’s. For the first time, many women who spent most of their time at home watching cable television saw relationships and women engaging in society in ways which they had never imagined was possible. It led to cultural movements for more equality for women in India. To me, that speaks to the power of media to affect change in the lives of real people. But I want to bring it back down closer to my personal story again…

I believe there is this process, that I participated in, in Hollywood that was not about any one studio exec or any one person but a collective process of debating and pitching and helping to bring stories to the screen where we all collectively decided what should be there. So many of us were trying to figure out what audiences wanted to see or — if we were to put a finer point on it — what people would pay money to see. And because there were tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars were on the line, it was completely rational to want to mitigate risk, but I think that it is this mitigation of risk that poses the problem. It it so so easy to stay in that safe space of the world that we think we know. So just like that guy in my fraternity who believed that what he should be doing is to defend his honor, we would fall bac on stories that perpetuated what exists in society, which was problematic.

When I was deep in the thick of the talent representation world, I was painfully aware of the competition for limited production funds. I had a sense of and tracked how many screenplays there were around town, then — moving down the funnel — how many of those projects proceeded into development at a studio, how many development projects got greenlit for production, and finally, how many were released into theaters. There was always the sense of “what makes your project better than the other ones out there?” And “why will it resonate with a larger audience?” At the time, I more or less accepted that sense of scarcity as just the way things were. There were projects I was passionate about, there were projects I fought for, but maybe where I went wrong was that I never really felt I had a story that just had to be told.

I was paid to make huge (often gender-based) assumptions about our audiences …

This sense of scarcity, I believe, goes hand in hand with the same fear that I experienced in the moment with the angry fraternity brother. As with that scenario, I can look back at my time in Hollywood from hindsight and say ‘I wish I had had more of a voice. I wish I had fought more for progressive ideas.’ But I can also say that I wasn’t the only one in that situation. If anything, I had a front row seat to watch how these decision were made and it wasn’t just me not speaking up, it was a ton of people not speaking up. And I don’t think that this is isolated to Hollywood, this exists in so many industries because speaking up is scary and speaking up is hard.

Which brings me to the present day and how this podcast has brought so many inspiring stories to me. So many stories of women who are heroes. Actual people who challenged massive power structures. The entire world needs to be aware of these stories. If more people were aware of these stories, I honestly believe it would fundamentally shift ways that we collectively view the world and how we relate to one another. So I’m feeling passionate. I’ve started picking up the phone and reaching out to friends who still work in entertainment. I feel more convicted than I ever did when selling stories was my job. One of the first friends I connected with is a producer, someone I’ve known personally and professionally for fifteen years, someone I respect. I described what I saw in these stories and his response was simple: “What makes that entertaining?” “Who watches that movie?” A part of me wanted to yell “Everybody!” while another part of me was so profoundly smacked in the face by this reality that I remembered vividly, but had been away from for so long. It all came rushing back to me in that moment and the thought that echoed through my head was, “this is how it happens, I’m watching patriarchy play out in front of me right now.” Over and over, throughout history, if someone considered sharing these stories how many times were these “who cares” questions asked? If patriarchy is the perpetuation of power structures that advantage a few white minds over most men and over all women, than these questions were the embodiment of a multitude of opinions by one of the most culturally influential industries in the world towards the value of women and a fight for equality that has been playing out for centuries.

The entrepreneurial side of my mind started racing around all of the ways to get these stories out into the world as books and tv shows and movies, fueled by passion and purpose, executed by exceptional artists achieving a global reach, generating mountains of cash and making traditional Hollywood studios look like Blockbuster after it passed on the opportunity to buy Netflix. How amazing would it be to crowdsource the equity of this studio so that women literally owned these stories and they were accessible to the whole world and generations to come! Amazing stories about women, created by women, for everyone. I want to live in that world.

If there’s one thing that the pandemic has taught us, it’s just how intimately we are all connected. It may have been possible in the past to ignore those connections, but now the suffering of some is so obviously the suffering of all of us and the world would be a better place if we could address some of that suffering. I want to be more brave. Contributing to this conversation with you all was definitely scary and I’m so glad that I did it. I want to be more aware of the existence of oppressive power structures like patriarchy so I can speak up against them when they present themselves in my life.

It’s time for all of us fish

to wake up.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!