“my body is an instrument, not an ornament”

On today’s episode I’m joined by Dr. Lindsay Kite to discuss the burden of beauty standards, self-objectification, uncomfortable compliments, and how we can strive to escape the cycle of normative discontent.

Our Guest

Dr. Lindsay Kite

Dr. Lindsay Kite is co-author of the book More Than a Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament (2020, HarperCollins) and co-director of the nonprofit Beauty Redefined, alongside her identical twin sister Lexie Kite. Both received PhDs from the University of Utah in the study of female body image and have become leading experts in body image resilience and media literacy. Lindsay and Lexie help girls and women recognize and reject the harmful effects of objectification in their lives through their social media activism, online course, and regular speaking engagements for people of all ages. Lindsay lives in New York City.

Learn more at morethanabody.org

The Interview

Amy Allebest: I’m so excited to have you here to talk about beauty standards and the role that patriarchy plays in these social constructs that we are taught and participate in unknowingly through our lives and are trying to push back against.

…representations of women had been manipulated: twisted into a really cohesive ideal that then caused almost all women and girls to feel abnormal, to feel subpar. And not only that we’re not beautiful, but that we’re just not normal. We don’t live up to the standards for what it means to look like a woman and what it means to be a happy woman, a healthy woman, one who’s desirable…

Dr. Lindsay Kite: It’s extremely relevant. So I think this is a nice little crossover we have going. Thank you so much for having me.

AA: It is an important crossover. As I did my first season of Breaking Down Patriarchy I was struck again and again by all these different books going all the way back to Mary Wollstonecraft in 1792 where she talks about how beauty is the woman’s scepter and she’s in this gilded cage seeking to adorn her own prison. And then Beauvoir talks about being perceived rather than being inside her body, and Kate Chopin talks about her husband monitoring her and observing her, so… I’m going to stop talking and just let you talk, but I thought one way into this topic would be a quote that you share in your book. It’s in Chapter 3 for listeners if you have her book – More Than a Body – and John Berger, who is an art critic (we’ve talked about him before) and his book – Ways of Seeing – but in More Than a Body they share this quote from John Berger:

“Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object”

Okay Lindsay, tell us about that quote and what that has meant in your research?

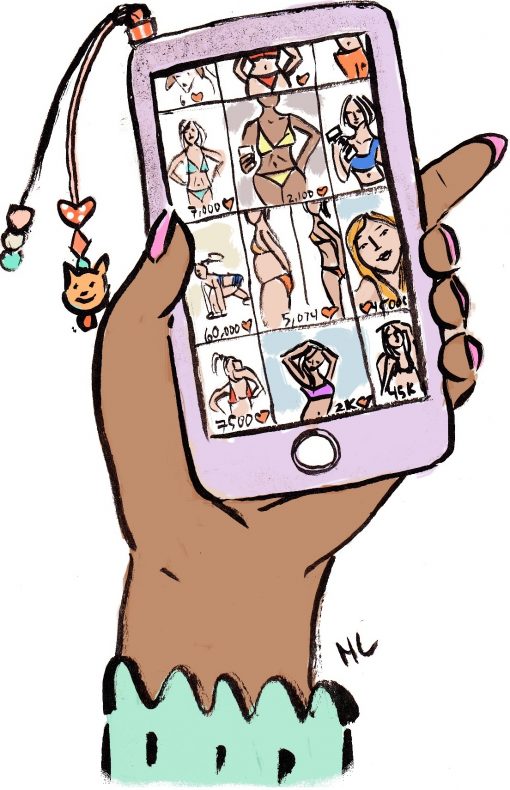

LK: Isn’t that a powerful quote? I feel like whenever people hear that it sounds like it would be something that’s really abstract and kind of tough to wrap your mind around. But as women we know what it feels like to survey ourselves, and in our body image research… so Lexie and I first got into this body image research through Media Studies. Early in college we started learning about the ways representations of women had been manipulated: twisted into a really cohesive ideal that then caused almost all women and girls to feel abnormal, to feel subpar. And not only that we’re not beautiful, but that we’re just not normal. We don’t live up to the standards for what it means to look like a woman and what it means to be a happy woman, a healthy woman, one who’s desirable, and so it creates this really warped worldview where we are not only feeling less than beautiful, but feeling less than human all the time. Of course there are so many complicating factors that make that harder for some people than for others. Lexie and I definitely felt the burden of it as soon as we started to recognize what it was and shedding light on it. That burden that we all face is one of the most important parts of it, because in our culture it’s perfectly normal for us to be embarrassed of our bodies, to feel defined by our bodies and by our appearance, and when you first start digging into all of the ways that we’re affected and how that shows up in so many areas of our lives…

we learn to relate to our bodies from the outside like we’re strangers looking in at ourselves

I think one of the most salient and important parts of our research is what we call self-objectification. It’s what John Berger described in that quote; it’s where we grow up in a culture that objectifies women’s bodies so severely that we learn to view and evaluate our bodies from the outside. So, in the beginning of our book, we talk about it in a kind of a metaphor where we split from our bodies. We grow up as little kids who are fully at home in our skin, in our bodies, we lack that self-consciousness and that disgust that slowly creeps into our lives. And one of the things that causes us to split from ourselves, instead of just being fully embodied and living within our dynamic and imperfect bodies, is what we call the “waters of objectification” or the “sea of objectification” that is absolutely surrounding us, that positions women’s bodies as parts to be looked at, to be judged, to be evaluated and consumed and discarded by others. And we slowly dip our toes into that water, or we’re invited into that water by people we know and love, people who see our bodies and comment on them, by the media; ideals that we’re surrounded by. It might be your older sister’s magazines that you pick up or what you observe in media or how your parents talk about their own bodies and things like that, and we slowly drift away from the bodies that we were at home in on the beach as little kids and watch ourselves from afar. Our body image becomes something that we think is viewable, something that can be improved by changing our appearance and fixing our supposed flaws instead of reconnecting with our own bodies. That split that we start to experience from the time we’re really little – and that split is self-objectification where we learn to relate to our bodies from the outside like we’re strangers looking in at ourselves, perceiving ourselves, monitoring and judging ourselves even when we’re all alone – it shows up in research starting from extremely young ages. Girls as young as 5 and 6 years old are monitoring their bodies from the outside, evaluating their happiness, their self-worth, their relationship to themselves by how they think they look to other people from the outside. I think that’s where the real foundation of all body image issues really starts.

AA: I remember from your TED Talk you talking about being a swimmer when you were a kid, and that at some point in your mind you made that switch where you were the swimmer, you were the subject of the action and you inhabited your body as an instrument, as you always say, right? And then at some point it switched and you’re like Oh no I’m being looked at! How do I look in my swimsuit? and it stole your love and your joy of swimming, which is so tragic.

LK: Yeah, it’s something that is really relatable for a lot of girls. A lot of the women that we’ve spoken to in our research can pinpoint a time when they went from being at home in their bodies, using their bodies as instruments, instead of looking at them as ornaments. It’s the mantra we use all the time: my body is an instrument, not an ornament. A lot of people can go back in time and remember a moment or an experience where they decided to hide or to fix their bodies instead of doing something that they really wanted to do. For a lot of people it was sports, it was dance, it was volleyball, basketball, swimming– things that they really like to do, even not going up for leadership positions or other experiences that would be visible, where they might be judged. That’s when girls start sitting out, when that self-objectification kicks in. We feel defined by our bodies. We pick up on all of the cues from other people that are fixated on how we look and how they look, and it sets us up for failure because that’s when we start to not live our fullest lives. We kind of live as shells of ourselves and hide and hope that we will be able to fix ourselves enough to have the confidence to get back in. But when we quit at young ages – I quit swimming when I was 15 after years of competitive swimming, and I did that because I was so self-conscious of these older high school boys that joined my swimming class for PE credits and I just knew that they were watching me and looking at me. And that self-consciousness set in to the point where I would be the first person in the pool and the last person out of the pool. I would pretend to forget my swimsuit. I would do whatever it took so that they didn’t see me in a swimsuit, even though I was a really good swimmer and really enjoyed it! That was the beginning of years of hiding and fixing that did not serve me at all. It’s like this in our culture; we’re given so many different paths to happiness and success, and almost all of those paths have to do with how we look and how other people view and value our bodies, especially how men, unfortunately, view and value our bodies. And we see ourselves through that same lens, hold ourselves to these standards that hurt us our entire lives.

…A lot of people can go back in time and remember a moment or an experience where they decided to hide or to fix their bodies instead of doing something that they really wanted to do.

AA: Yeah. That brings me to one of the questions I wanted to ask you which is tricky to untangle, at least for me in my own personal life, because as I look back on the first moment that I had, that moment of like oh I’m being watched and evaluated it was a woman who made me feel evaluated. I remember in The Second Sex when Beauvoir talks about that. She’s quoting one of the women that she had interviewed for her research and the story that was shared (and this was in the 1930s in France) it was a dagger because it was just exactly like my experience. It was her mother saying Don’t you realize you can’t wear that short of a skirt? Pull your stockings up! and she suddenly was aware of herself as you know you’re being looked at.

So what I was going to ask is: We as women do this to each other a lot – in fact, a lot of the enforcing of beauty standards happens from women to other women, whether it’s modesty or body shaming or size shaming or whatever women do to each other – but there is a patriarchal construct that’s behind it or underpins it in some way.

I’m wondering if you could talk about that because you mentioned that, in your case, it was watching teenage boys watch you and I certainly have tons of experiences like that too. But it’s sometimes women enforcing it. So what role does patriarchy play in all of this?

LK: Yeah, that’s a really good question because I think sometimes when people hear ‘patriarchy’ they think ‘men’, and so when they think of their experiences that first made them feel self-conscious or embarrassed of their bodies, a lot of us can tie it back to women – whether it’s our moms, our sisters, our grandmas, aunts, or teachers, will say things. And I think that’s really important to note. That objectification is really the foundation of everything that Lexie and I do through our research. When we see our bodies as objects, we learn to view and value them as objects to be looked at, to be used and consumed by other people, but that’s very much hand-in-hand with patriarchy. It’s a byproduct of a patriarchal culture where men have most of the power and where we learn to view ourselves through a male perspective. We learn to prioritize a male perspective on women’s bodies, on our own bodies, because we grow up in this environment that positions our bodies as sexualized. And in that sexualization, they are either assets or threats and so other women do the work of trying to protect their sons and their husbands from these threats of our sexualized bodies– the distraction of them, the temptation of them, the thoughts that they may cause. They’re also seeing other women and girls as objects to be viewed at the same time. Sexual-objectification is really the root of all of this and when women step in and do that work of policing and making things more favorable in a patriarchal environment, where men’s perspectives are privileged, they’re often seeing other girls and women not only as threats, but as competitors. Sometimes it can come from a couple of different angles, and we learn to see other people as competitors for limited resources that we want to have access to, whether it’s attention, validation. Sometimes it’s resources. Sometimes it’s positions of power. Many of these can be tied back to making sure that men see our bodies favorably, or making sure we’re not a threat to men in positions of power, men who may potentially be looking at our bodies. And so women are often the ones doing the gatekeeping in this way, either to make sure that other women and girls aren’t competitors for resources or attention (whatever it is that they also want in that environment) or protecting the men and boys in their lives from these potential sexualized threats. It’s very much a complicated issue, but this sexual objectification and patriarchy are completely intertwined.

AA: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Thank you for that, and as you were talking I thought also – as I’m picturing, you know, these really well-meaning grandmothers and mothers and aunts and teachers who’ve been breathing this air their whole lives too and they are taught again – this Wollstonecraft quote comes back to mind of how women are taught “beauty is woman’s sceptre”. So there’s that whole thing about (and I know you’ve talked about this on Instagram too) how we praise little girls for what they look like and we tend to praise little boys for what they do and ask questions about well, what are you doing? I’m so embarrassed, but I did it this morning! Lindsay, I’m just realizing I did it this morning! When my kids were getting ready for school (I have a daughter and a son at home, still in school) and they came out, I said oh, Sophie you look so pretty and then my son Stone walked out and I thought… it just wouldn’t occur to me to say Stone, you look so handsome, right? I mean I would just say something else that’s nice to him. So even me (and I like to think I know better) but I think subconsciously we all know, like you said, that men hold most of the power and that woman’s beauty is her scepter. And so mothers, especially those who aren’t aware, are probably trying to give their daughters as much power as they can because that’s our only power so— be beautiful! It can be really judgmental. That’s so shallow, it makes me so mad. But then I can be kind and compassionate and think: Listen, if that’s the only power that she’s ever had in her life, then she wants her daughter to be prepared to use whatever power she can get in this world, even if it’s not conscious.

LK: It is so true. And it’s such a double-edged sword because I think that compassion really is key. We can look at women who are upholding patriarchal standards and enforcing objectification and sexualization on other girls and women. But you’re right, when that is the power that they’ve known through their lives, when it’s proximity to men, approval from men… you know, it’s the proximity to power that I think so often women are trying to make sure that they have access to and are rewarded by. But they also make sure their daughters get close enough, but not to the point where it’s a threat to men, not to the point where it’s a threat to other women or where they are in danger of being preyed upon by men who don’t have their best interests in mind. It’s tough because we feel like our beauty and our sexual appeal, in some ways, are our recipe for success. It’s the key to being able to have all the power we know about in this world, that women can have access to, and a lot of that power and validation feels really good. It feels like the best rewards that a lot of us can imagine – especially when you haven’t been around women who gain power in other ways, and who really find fulfillment and worth in other aspects of their lives outside of their physical appeal and their proximity to men and how men perceive them – when we don’t have access to that, that’s kind of all we can envision.

As you know, as moms and as female leaders we want that for our girls, we want them to be valued and happy and to find love and validation and all of that, and so it becomes what feels like an innate thing to say oh you’re so cute. We think that it’s only natural that we think of girls as cute and we value and praise that, when really this is learned behavior. This is pure socialization that teaches us to see girls as passive and boys as active and then to value those attributes in both of them. We’ve got to unlearn that, and I’m not shaming you at all, I do the exact same thing with my little nieces. Of course I think they’re the cutest things in the whole world and I want to tell them I love your little outfit and your little cheeks and whatever. Even being immersed in this research for so many years, I have to actively stop myself and remember to ask them questions and to talk about the things that they are doing, not just how they’re appearing. It is a constant battle in this culture that really values the way girls look more than who they are.

AA: Okay, here’s another question then. This is something that my husband just said the other night – and we laugh about it – but I’m like oh man, I feel for him. He started saying “You look pretty… but that’s not the most important thing about you, and you’re really smart and you’re really interesting.” So we’ll laugh, but he did say the other night on a walk, “I actually really don’t know if I can tell you you’re pretty anymore. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? What should I do? Am I allowed to think that you are sexy? Am I allowed to think you’re beautiful?” And I thought man, the poor guy! He’s trying so hard to do it right and I so appreciate his effort, but I think the thing is (and I’d love to hear your thoughts on this) I also say to him “Wow, you look so handsome” or “That shirt looks so good on you” or whatever. I give him compliments about his looks because it’s part of him. But I said for me, as a woman, I feel like because I’ve been so limited that that’s all I am, it just lands differently for me. But because he gives me compliments on the way I look as a small percentage of the overall positive comments he gives, I said that it works and it’s great. But I do wonder if men are just like, I don’t even know what I can say to my wife or to my daughter. If she does look pretty am I allowed to say it? How do you coach men on this?

We think that it’s only natural that we think of girls as cute and we value and praise that, when really this is learned behavior. This is pure socialization that teaches us to see girls as passive and boys as active and then to value those attributes in both of them. We’ve got to unlearn that…

LK: I think that’s a good question, but what a wonderful thing for a man to grapple with. I think it’s such a testament to critical thinking skills and the ability for people to evolve and think in new ways without this extreme defensiveness that we see in so many people when you push back on this idea that maybe we shouldn’t be solely focusing on appearance and constantly reminding women that we’re looking at them and that we like or don’t like how they look, which can be really triggering for some people. Even in the validation and the good feelings that it can bring up, it can be a constant reminder to reflect back on your appearance, how he might be seeing me and how I can change that because I’m not getting the compliments I want and all of that. Your husband is clearly grappling with that. It’s something that we all should be doing, not just for the people that we love, but also for ourselves and where we’re getting our value. So I think that in itself is absolutely wonderful, it’s exactly what you need to be doing and you’ll come to the right answers yourselves because you’re able to have an open conversation about it. It’s not like you’re saying, I was valued for my looks my whole life, it’s the only thing I cared about and so now when you talk about my looks I feel like you’re demeaning me. It’s not that you’re ungrateful to have a compliment. You’re grateful that your husband is attracted to you and we’ve got to get away from this idea that sexual attraction is bad or wrong or is inherently objectifying. It’s not, because sexual attraction is natural, it’s crucial for a romantic relationship and it’s grounded in so much more than just how you look. There’s so many facets that make you sexually attracted to someone outside of thinking they look hot. And I think we value that when we have really open conversations with people about the ways we’ve been affected, not only by beauty ideals, but by sexual ideals and how it’s affected our sex lives, the way we perceive our bodies, even the way we think about ourselves and about other people in moments of intimacy.

Women are really at a disadvantage when we’re thinking of how we appear to our partners while we’re engaging in intimate acts or having sex, because when you’re self-objectifying you don’t experience as much pleasure. You are held back from really being able to have a human, emotional, physical connection regardless of what you’re doing, and I think a lot of men take that for granted. So by having an open conversation and saying, “I’m grappling with this stuff right alongside you and I’m trying to figure out healthy balances for me, but I really appreciate you working with me on this…” We’re going to get rid of some of that defensiveness. We’re going to get rid of some of the hesitation to even compliment that might cause space between us. We get rid of that by just being open and honest. And those thoughts may change as we continue to learn about ourselves and what brings us value and what distracts us from our real value. When I talk to men about it I generally say… well, first of all I’m usually talking to women, and the way you reach men is often through the women in their lives. A lot of men don’t care about this stuff until they do care about a woman and, unfortunately, it is easier to reach men through the women they care about. So when I talk to women who are in romantic relationships or seeking them (and not even just romantic relationships, but relationships with male colleagues and older male family members and things like that) all of this comes up where the compliments might circulate around appearance and that can be something that reinforces this limiting view of ourselves. I tell women to have frank, open conversations with men that they feel comfortable with to be able to say Hey, I’m really working on valuing myself for more than my appearance, so thank you so much for your compliments and if you notice anything else about me that you appreciate or that you like — and it doesn’t have to do with my beauty — I’d love to hear that stuff too, because sometimes it’s hard for me to really get a grasp on those. It’s vulnerable. It might be uncomfortable for some people, and that’s why I say to talk to men that you trust. But when you can be a little more open about it, it’s disarming to people. It makes them less defensive. It makes them think twice and be more open. Not only in the way they talk to you, but in the way they engage with and talk with other women in their lives, and that is a good step.

AA: That’s true. Okay, another question on a similar topic. Actually it’s these conversations that I’ve been having with men for a long time, but especially in the past year. I was talking with a couple of men – and these are good men, these are not jerks, these are not misogynistic people — but we were talking about compliments, less between spouses and more like getting whistled at or the one that I shared was stuff that, to me, actually felt really scary. I remember in middle school (and thank goodness so far my kids have told me things are not like this in their schools anymore, at least where they’ve gone to school) but I got very sexually explicit comments when I was young, like 13. I was telling these men about some of the things, like notes that were passed to me in English class in eighth grade, and I was honestly pretty hurt and really surprised by these men’s reactions. Because they were like Oh, well that was a compliment or Oh, I would have been stoked if a girl had said something like that to me. I couldn’t make them understand why it felt scary to me, why it felt objectifying, and that objectification felt really awful and really scary. I couldn’t help them see why because they were just like What, they thought you were cute or they thought you were hot? We wanted girls to think we were hot, so what’s the problem? Do you not want guys to be attracted to you? And it was kind of an ignorance of this power difference. Do you find that in your research, or do you have any advice for women who find themselves in conversations like that with men?

LK: Yeah, ‘ignorance’ is definitely the right word for it. Especially when you’re talking to men who consider themselves to be a little more open, a little more aware of gender relations and the ways that has harmed women. You’ll still get that reaction like you described that minimizes something to a compliment, or says you should be flattered. I’ve experienced that a bunch of times. I’ve tried to describe to men how unbelievably obnoxious it is to walk past a man who says Hey, give me a smile or Turn that frown upside down when I am simply thinking and walking down the street. I don’t owe a smile to anyone, and that’s a really common thing for women to experience. And the men that I’ve told about that are absolutely floored because they have never asked someone to smile and they’ve never seen it happen and they can’t even imagine being on the receiving end of being demanded to smile by someone who just wants to see your pretty face. So it’s like you’ve got to shatter the glass for men, that even though they haven’t personally witnessed or engaged in that kind of sexual harassment… a lot of time, especially when the comments are about your body and are often very vulgar, like I live in New York City where I get crazy comments all the time, and how do you know which ones are threats and which ones are just a nice guy trying to give you a compliment? You don’t.

AA: Right. You don’t.

LK: You don’t know because men feel entitled to women’s beauty and women’s bodies. And the rates of sexual violence are absolutely outrageous and it often comes from people that we know, not strangers who jump out from dark alleys (although that is absolutely a risk that women experience every single day). So for men, sometimes it’s a point of driving home that women are at risk of violence, that you don’t know how to tell which man is going to lash out at you for not responding to his kind compliment about your smile or your body on the street. And you don’t know which one is going to let you go without a fight, because a lot of them, a higher percentage than they are even aware of, will get back at you with really negative, angry remarks. They might follow you. I’ve been followed. I’ve had terrible things yelled at me when I refuse to comply to somebody’s demand to smile or to accept their compliment and say thank you, and they continue to ask you questions. Men need to be aware that this is a serious thing. This isn’t a matter of compliments and nice words and flattery. Yeah, I’m single and dating. I do want men to find me attractive, but I want it to be the men that I want to talk to, not just anyone who feels entitled to a reaction from me on the street.

Women are really at a disadvantage when we’re thinking of how we appear to our partners while we’re engaging in intimate acts or having sex, because when you’re self-objectifying you don’t experience as much pleasure

Another point to really drive home to men is that, especially in their younger years, boys’ bodies change in ways that get them closer to male physical ideals. Girls’ bodies change in ways that put them further away from female physical ideals. We get more fat on our bodies. We grow hair. All of these things push us further away from the physical ideal for women (that is absolutely prepubescent, with large breasts tacked on) whereas men get more muscle. They get facial hair and body hair. They grow in size and that makes them feel better about their bodies while girls get infinitely more insecure, and that is right around the same time of life when the comments start to come from strangers and from people that they know. And so while of course it’s nice to get validation in a culture that values beauty more than anything, it’s also a little rattling. It can be threatening and scary because, again – even if it’s a boy in your class who passes you a note or sends you a text – you don’t know how he’ll respond if you spurn that advance. You don’t know, and you hear horror stories all the time.

And another thing is that men get their value and validation starting in school and starting from even younger than school age from so many different areas. They’re getting their attention and real self-worth and confidence from their athleticism, their intelligence, their success, and skills in all areas of life: their sense of humor, and also from their physical appearance, but very rarely just for their physical appearance. And yet girls, all the time, are getting either validation or insults that are solely based on their physical appearance and how other people perceive their sexual appeal. So it is not a compliment all the time to have that be the sole focus of other people on you. It’s disproportionate when you know that you are so much more than just something to be looked at. And so to get that constant reminder from other people, even boys who think they’re just trying to give a compliment, is unsettling. It creates this worldview that’s really distorted and really narrow that can last for your whole life, whereas most boys aren’t dealing with that side of things, that narrow perspective on their confidence and self-worth and value.

AA: Wow, that’s so important. It occurs to me too that if they were to get some negative comment about their looks– I mean, I guess this is what you’re saying– they have so many different facets of themselves that they can fall back on for their self-esteem. And women don’t hold power over men in their political life, in their spiritual life, in their religious life, in legislation, in every aspect of their lives. But for a woman, I think what I was sensing even when I was a girl who hadn’t really read any of the data about sexual assault or anything, I could sense on a very basic level, on a biological lizard-brain level, you could hurt me in a way that I can’t hurt you. And also I had already been trained in patriarchy to see… you are male I am female; not only could you hurt me physically, but I need to please you because you outrank me in all of these different ways. And so to stay safe I have to laugh at it– like you’re pretending it’s a joke, so I guess I’ll just laugh or say nothing or just smile. I can’t stand up for myself because even though he’s just a doofus, I’m a 13 year old kid too! But I had already been trained in this matrix of power and the way it worked for male and female, so it’s false equivalency for the man to say Well I would want a girl to say that to me. I think you just helped me learn more about why that felt so deeply uncomfortable and what I was not able to articulate to those men that day when I was trying to explain it.

LK: I hope more men are willing to be open-minded enough to see that when we say something is unsettling or something doesn’t feel right on some level or feels a little threatening, that they would be able to see that there is something more to that. I know that men are really quick to dismiss women’s complaints of being objectified or having only compliments directed to how we look and people of power only giving attention to how we appear. I think that it’s an easy thing to do. Of course it’s natural for a man to only think from his own perspective. But so many times as women – especially in a patriarchal environment – we have been taught to view the world through men’s eyes. We’re doing the mental gymnastics to read literature, to hear speeches, to…you know everything is written and spoken from a man’s perspective and so we do the mental gymnastics to change the pronouns, to change the perspective, to make it work for us, to try to make the mental leaps to fit it into our worldview and our experiences. And men just aren’t trained to do that. They rarely have to do that when they’re growing up, whether in school, in church, in whatever other environments they’re in, and so as adults I think it can be more challenging for men to have to change their perspective, to make women’s perspectives more salient in their own lives. I think men need to be challenged to do that and it’ll be helpful for all of us.

AA: I absolutely agree.

One last question, Lindsay. This has been so illuminating, but if you could sum up the advice that you would give to women about how to deconstruct patriarchy in our own minds – and that can be specifically about beauty or it could be more general – but what have been some things that you found in your own personal life and through your research that have been useful in deconstructing those things that we’ve been absorbing through our whole lives?

…everything is written and spoken from a man’s perspective and so we do the mental gymnastics to change the pronouns, to change the perspective, to make it work for us, to try to make the mental leaps to fit it into our worldview and our experiences. And men just aren’t trained to do that.

LK: Yeah, that’s a good question. So our whole book, More Than a Body, is about this. It is very much about being able to see the objectification in our environment and the ways it has directly affected our self-perceptions, our relationships with our body, the way we engage with other people and the world including our own families and in interpersonal relationships and the choices that we then make going forward. Unfortunately, without being able to see that objectification and the ways it has actively harmed us and held us back, we just continue in these same cycles where we are in the waters of objectification. We feel pretty comfortable there until what we call a “wave of disruption” comes in and knocks you over, and that’s something that stirs up shame about your body. It makes that body anxiety come to the surface. Think negative comments about your body from somebody, or going through a pregnancy or a miscarriage or a breakup, or anything else that we blame on our own bodies. In coping with that shame, so many times we will stay in the same cycle of hiding and fixing like I described before. We do excessive dieting. We do disordered eating. We engage in all types of substance use and abuse and try to fix our bodies to fit these ideals so the shame will go away. And unfortunately it doesn’t last and we stay in this uncomfortable comfort zone of what we call “normative discontent” where it’s perfectly normal for most of us to feel uncomfortable in our own bodies.

For Lexie and I, our whole mission, our work revolves around helping people to see a new way out of that cycle so when that body shame comes up, when you feel the objectification really having a negative effect on you in your life and causing you to sit out and hide and fix, we provide these tools so that you can make a more resilient choice to build that body image resilience muscle. It incorporates your critical thinking skills and media literacy to be able to see how your body image environment, through social media/mass media, stuff that you don’t even see because it’s so invisible in our lives, you can learn to curate that in a more helpful and empowering way for you where objectification isn’t so unquestioned and just the wallpaper of our lives. It includes the ways we think about our own bodies and the self-objectification that has become so normal for us. I think one of the baseline things that we all have to be able to do is to filter our whole life experiences, our daily activities, our thoughts about ourselves through this lens of prioritizing how we experience the world – not how the world experiences our bodies – that can help you get back inside your body. We’ve got to be reconnected to ourselves, our own physical bodies, these dynamic bodies that we were born into that we have lived every second of our lives in, instead of thinking of them as these embarrassing projects that we will be fixing our entire lives.

We can stop splitting from ourselves and instead come back home to our bodies as our own, our place of refuge, and stop looking at them from the outside. And when we build our body image resilience, we see the patriarchy, the objectification, the things that are separating us from our bodies and causing us to look down on them and to devalue them. And every time that that shame comes up, every time this objectification in our world slaps us in the face and says your body is the most important thing about you, we can stop. And breathe. And remember that I am more than a body – my body is an instrument, not an ornament – and respond in these resilient ways to change our environment. Not only for right now, for us individually, but collectively: our families, our communities, the groups and organizations that we’re involved in. We can dismantle this normalized objectification and the patriarchy that stays so ingrained in our minds and the ways we view and value our bodies and change that, not only now but for the future. So it’s obviously a big question, but when we prioritize how we experience our lives instead of how the world experiences our bodies, we take back a lot of power.

AA: That’s powerful stuff. Lindsay, thank you so much. This was a fantastic conversation, honestly helping me illuminate some things that I’ve been wrestling with and trying to untangle and I know listeners will be so grateful. Thank you so much for being here today, I learned so much.

LK: Of course. Thank you so much. I really appreciate all of your perspectives that illuminate this conversation so much. So, thank you.

I get crazy comments all the time, and how do you know which ones are threats and which ones are just a nice guy trying to give you a compliment?

You don’t.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!