Throughout history women have been misrepresented as villains and monsters: witches, demons, succubus, and beyond. And this misrepresentation of our bodies and minds as evil is no accident! Rather, the vilification of women is a practical tool of patriarchal systems which remains painfully relevant today. After all, if we cast women as monsters, that must make the men controlling them heroes—and who would want to listen to the words of a she-demon? Who would want to vote for one?

The damage caused by this vilification is long lasting, so in order to help us unpack some of its history and present-day impact two remarkable women joined us for this episode — Dr. D’Vorah Grenn and Lucy Allebest.

Lucy Allebest who shares her research and insight into the history of witch hunts in Early Modern Europe and the American Colonies.

Dr. D’Vorah Green who tells us about her study of Lilith, demonization, and her own rebellious journey.

Our Guests

Lucy Allebest

Lucy Allebest (she/her) studies History at the University of St Andrews. She enjoys dancing, organizing, wearing green, and sleeping at any time of day or night. Her greatest joy is hugging her parents and her greatest fear is the Pixar lamp. She hopes to one day do something interesting enough to write a bio longer than sixty words.

D’Vorah Grenn

D’vorah J. Grenn (she/her) Ph.D. and Kohenet, is Founding Director, The Lilith Institute (1997). She co-directed the former Women’s Spirituality MA Program at Institute of Transpersonal Psychology/Sofia University, and founded Mishkan Shekhinah, a movable sanctuary honoring the Sacred Feminine in all traditions. D’vorah leads the Institute’s Lilith’s Fire Circle, does a “Tending Lilith’s Fire” broadcast/podcast with Kohenet Annie Matan and also serves as a spiritual mentor and guide.

PART ONE.

Lucy Allebest

Today, I will be talking about witchcraft in early modern Europe and the American colonies, and how it relates to patriarchy. Disclaimer: this is not about people in the past or present who identify as witches or practice witchcraft intentionally. So when I talk about witches, I mean people who were accused of supernatural crimes many centuries ago. Let’s get started.

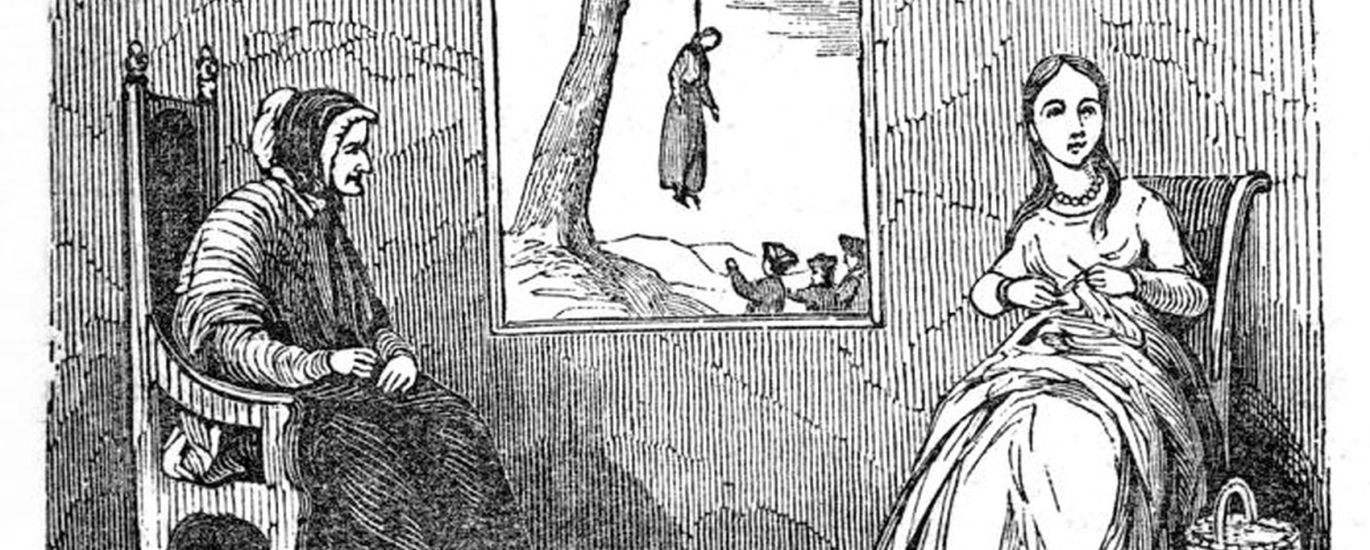

Throughout the 14th to 17th centuries, thousands of people — most of whom were women — were accused of witchcraft and executed. Over the years, experts on the history of witchcraft and gender studies have explored some very compelling connections between the witch trials and patriarchy; a history which I intend to explore. I should warn you. Some of this history is disturbing, but for me personally, the sexist roots of the witch trials are the most disturbing part. Before we get into it, I should mention that one of the main sources I’ll be referring to is the book, Witches and Neighbors by Robin Briggs, specifically a chapter called ‘Myths of the Perfect Witch’.

In this chapter the author, an Oxford historian. emphasizes the importance of age and reputation in identifying witches, with the majority of the accused being “pathetic, old, women, whom their neighbors found obnoxious.” So, who were these accused witches? Primarily, they were elderly and unpopular women (although of course there were exceptions). That said, even though Briggs describes these typical characteristics of witches, he then kind of contradicts himself writing “witchcraft was neither gender nor age specific for these artists any more than it was confined to one social class.” Perhaps we could look at it like how people of all demographics are pulled over for traffic stops in the US, but Black drivers are 20% more likely to be pulled over than white drivers.

Some of this history is disturbing, but for me personally, the sexist roots of the witch trials are the most disturbing part.

It’s also difficult to know the precise statistics because witch hunters didn’t exactly leave us detailed spreadsheets of who they were interrogating and murdered. As for the persecution of accused witches many, if not most, victims were thrown under the bus by people, they knew personally, this is partly because naming other witches was a quick way to stop torture or expedite your execution if, say, your thumbnails were being drilled by screws… However some accusations were made because people either genuinely believed someone to be a witch or because they hated them and wanted to see them killed in public.

Having established who the witches were, let’s turn to what they were accused of. Robin Briggs also wrote extensively on this, explaining that the public believed witches were engaging in all sorts of crime, but highlights were kidnapping, infanticide, bestiality, and having sex with the devil. There were many stories of witches flying around at night and eating babies, and people would really make up anything disturbing to challenge what society saw as moral. There was a huge emphasis on women’s sexuality and sexual sins, but we’ll go in depth with that in the few minutes.

A lot of the activities that witches were rumored to partake in, like eating babies, were obviously unethical and disgusting, but some of these rumors can actually help us understand the fears that late medieval Christian Europeans carried around with them, fears that most of us don’t find so scary these days. Some examples include dancing, eating with bad manners, and worshiping pagan goddesses.

Hans Peter Broedel, a history professor at the university of North Dakota writes extensively about witches relationships with the supernatural and heretical in his book, The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft.

And for context, he’s specifically analyzing the Malleus Maleficarum which was a German book written around 1486 and is considered the go-to literature for 15th century witchcraft. At the time, it was a sort of manual for how to identify and then prosecute witches, but now it serves as a snapshot of the witch hunters fears and social customs.

Broedel describes the rumors of women leaving at night to “attend the court of a goddess or spirit, often identified as Diana, and these ideas smacked of paganism, idolatry, or worse”. This particularly angered church leadership and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that they were especially offended by women sneaking around behind their backs to worship female deities. Would the punishments have been as severe for men gathering to worship Zeus? Maybe, but I predict that the outrage would be focused on the departure from Christianity, not the breaking of curfew or the gender of the pagan idol.

…many, if not most, victims were thrown under the bus by people, they knew personally, this is partly because naming other witches was a quick way to stop torture or expedite your execution if, say, your thumbnails were being drilled by screws…

This takes us to the connection between witchcraft and sexuality. Broedel writes “witches were adulteresses, murderous midwives, and evil mothers, women defined by the authors as personifications of feminine sexuality. Witches’ relationship with the devil was not defined in terms of conventional notions of heretical cults, but through sexual relations. The witch did not worship the devil, she slept with him.”

In my reading, I noticed this obsession with female sexuality that had many manifestations during the witch hunts victims of witchcraft would claim that they were raped by the devil while witches themselves were thought to have voluntarily slept with him. In the Malleus Maleficarum and other primary sources, there are very descriptive accounts that were very strange and kind of awkward to read. For example, when discussing the effect of witchcraft on sexual performance, the Malleus Maleficarum states “When the member is in no way stirred and can never perform the act of coition this is a sign of frigidity in nature, but when it is stirred and becomes erect, but yet cannot perform, it is a sign of witchcraft.”

In reference to this type of writing, Briggs describes the emergence of “scholarly pornography.” The amount of detail seems like overkill, and makes me wonder if this writing was an outlet for perverse curiosities about sexuality rather than actual supernatural investigation. My guess is that this was a side effect of the rigid Christian purity culture, especially around the time of the Reformation. Treating women’s bodies as both sacred and shameful is going to spark curiosity that could be explored and exploited under the guise of witch hunting.

Broedel elaborates on women’s dissatisfied sex lives as motivating their witchcraft. He says “the most malicious of women were the most lustful and the most less full of women were witches, whose sexual appetite was insatiable.” I have to admit I found this surprising seeing as a lot of strict religious communities and many parts of modern America characterize sexual desire as something that men experience, and women just deal with. And over the past several decades, we’ve seen movements for sexual freedom and better education on women’s health and sexuality, but I thought of it as a relatively recent development. So while 14th to 17th century Europe clearly stigmatized female sexuality. At least they didn’t ignore it completely.

But sexuality in relation to witchcraft was not just something that was hinted at through rumors. It was brought out into the open by investigators. One way that witches were identified was by finding a spot on the skin — a freckle, mole or anything that looked different — which they believe to be the devil’s mark. In Scotland, there were groups of ‘professional male prickers’ who would search the accused woman’s body for this mark, which they often conveniently found on her back, thigh, or what they called “privy parts.”

Within such a patriarchal structure, all of the investigator roles and all of the legal positions they would report to were held by men. British and Western European women were not allowed to get a law degree until the early 20th century. So back up 300 to 700 years and I can’t even imagine how helpless and accused woman would feel looking at a stand of male judges and jury who got to decide whether she lived or died a horrible death. Yes, it was often women who accused each other and women could serve as witnesses, but when it came down to taking legal action, the power was entirely in the hands of men.

Now, as I mentioned in the beginning, not all people accused of being witches were women. Women made up the majority overall, but there were actually some regions where more men were accused than women. I read one journal article called ‘Your Wife Will Be Your Biggest Accuser; Reinforcing Codes of Manhood at New England Witch Trials’ by Richard Godbeer. From the title we know that this focuses on American colonies, but I’m still including it because it’s within the time period and obviously white colonists in the 1690s were Europeans themselves or their grandparents had been. Godbeer talks about the differences between men and women and their supposed supernatural behavior and consequently, how they were punished. Many male witches were drawn in because they were related to women who were already accused — hence the title ‘Your Wife Will Be Your Biggest Accuser’.

Along with all of the women who suffered from the witch craze, there were also heartbreaking stories in Godbeer’s, Broedel’s, and Goodare’s books about men being condemned because they presented typically feminine characteristics and therefore violated “godly masculinity.” This perceived femininity could be because a man specialized in herbal healing, which could be seen as both heretical and overly nurturing for a man, or it could be a case where a man was suffering domestic violence at the hands of his wife and then he was the one blamed for being “even more feminized, weak, bedridden, domesticated, and dependent.” This podcast has already discussed how patriarchy and gendered values harm everyone regardless of sex, but I think these examples demonstrate just how far back the persecution of men under patriarchy goes and how detrimental it can be. We are used to victim blaming being targeted at women, but in these cases, men were triply abused: first by the society that expected them to be dominant to the point of aggression, then by their actual abuser, and finally by a legal system that executed them for not being manly enough.

There were also cases in which this dynamic was directly inverted, but equally problematic. Godbeer describes men who are supposedly possessed by the devil to beat their wives; while it is good that these men were punished for their violence, I take issue with attributing this abuse to supernatural influence. If demons are blamed for a man’s anger issues, the root of the issue is completely missed and everyone is robbed of their agency and accountability.

Goodare discusses the double standards of witches by gender, as women could be prosecuted simply for insulting a neighbor under charges of satanic cursing or illegal slander. Additionally, male witches were not nearly as sexualized as their female counterparts. It was rare to suggest that a male witch slept with the devil because Satan was not a woman. And if the man was suspected to be gay, well, then they’d already be punishing him for that. Investigators also skirted the violating investigations of men’s bodies. And because it was normalized for men to be in touch with their sexuality, there was nothing to condemn if a man was found to engage in heterosexual sex.

Treating women’s bodies as both sacred and shameful is going to spark curiosity that could be explored and exploited under the guise of witch hunting.

In his discussion of the devil’s mark and feminine sexuality, Goodare writes “the devil’s mark was sexual for women, not so for men; they sealed the demonic pact by sexual intercourse with the devil, man did not. As witches their alleged wrongdoing was connected with their allotted female role of motherhood. Men’s wrongdoing had no clear focus. ranging freely (like the rest of men’s lives) over a spectrum of public behavior. Witch hunting was to a great extent, an effort to control and come to terms with women’s sexuality.”

I also wanted to share some stories from Briggs and Goodare that encapsulated the misogyny of the witch trials. In 1596, a French woman had been brutally beaten by her husband and was turned away by neighbors when she asked for food and money. Those neighbors then accused her of witchcraft because they believed that she had cursed and/or killed their livestock in vengeance. In jail, she attempted suicide because she could no longer stand the torture. After all that, she was pronounced guilty and was strangled and her body was burned. Even if the woman had killed some cows, there’s no way to justify the amount of suffering that she went through. Briggs included several of these cases, but one quote that really stood out to me was in reference to a woman who was “alleged to have told another woman that she should imitate her practice of giving no sign when angry” because loud, aggressive women were much more likely to be named witches. I found that so troubling because of how relevant I think it still is. It’s been mentioned before in episodes that women have continuously needed to censor themselves in order to not be labeled as overly emotional. Thankfully in most places now it’s rare for expressive women to be executed, legally at least, but it still happens. And I think women still frequently tone down their reactions in front of men, even when their lives aren’t at risk.

My final example from Goodare’s explanation of how these women were punished has to do, again, specifically with the Scottish witch hunts. He writes that sleep deprivation was often used for several days and nights in a row as a form of torture that wouldn’t be legally considered physical torture. That level of sleep deprivation apparently would lead to hallucinations that could then be used against them as further proof of insanity or witchcraft. This disgusting manipulation reminded me of ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which the podcast covered in Episode 16 of Season One. There’s something so humiliating and cruel about messing with a person’s mind, especially someone so vulnerable to the point where they prove the manipulator. Whether it’s Gilman’s narrator who is gaslit into insanity, or an accused witch whose torture induced mental illness is used in trial against herself. It seems like a practical joke taken way too far, but this amount of cruelty should have been against the law, not supported by it.

In this final stretch now I’m going to talk about the societal expectations and manifestations of patriarchy in this context. Broedel’s criticism gives the most evidence for the distrust of women in early modern Europe. Broedel quotes the authors of the Malleus Maleficarum “since women are deficient in all strengths, as much of mind as of body, no wonder they cause a great deal of witchcraft to be done to those who oppose them.” Broedel continues the summary of their opinions: “Intellectually, women are childlike. So feeble-minded that they are of a completely different order for men. Their minds are warped, twisted like the rib from which Eve was first formed. And just as the first woman could not keep faith with God, so all women are faithless. Their will too is warped because they are inordinately passionate, more prone to violent love and hate, and so often turned to witchcraft to gratify these desires. Women are natural-born liars, proud and vain, and their hearts are ruled by malice. All of these defects make women the devil’s ready dupes or willing slaves.”

I don’t know if there’s anything really to say about that. Those are the direct words or summaries of the words of Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Springer, authors in late 15th century Germany. The deaths of tens of thousands of women were not coincidental, or even based on subconscious prejudice: they were results of violent outright misogyny.

Godbeer writes about how dangerous it could be for a woman to threaten her husband’s authority and how this reflected society’s fear of women with power. The structure of society as a strict patriarchy extended from the government and directly into home life where the husband or father had “ultimate authority.” Godbeer explained that “women whose circumstances or behavior seemed to disrupt social norms or hierarchies could easily lose their status as handmaidens of the Lord and become branded instead of servants of Satan.”

This already sounds harsh, but the specific stories that he tells shocked me with how quickly the line could be crossed. In 1645 Connecticut, a woman named Ann Hopkins was ex-communicated and accused of witchcraft because she had taken to reading and writing and abandoned her household duties. She was charged with “usurping authority over him whom God has made her head and husband.” There was no mention of her being abusive or loud or suspicious in any way, but she was seen as a threat to her husband’s authority and the order of the town, because she stepped out of her designated sphere.

Finally, I found a passage from a feminist newspaper from the early nineties where Judy Molland published an article called ‘Of State Hearings: Witch Trials and the Terrible Fear of Women.’ In her article, she draws parallels between the then recent testimony of Anita Hill against Clarence Thomas and the history of witch hunts, including the Malleus Maleficarum. Molland writes about the vulnerability of women, such as Anita Hill and the possibility that if she had been born three centuries earlier, she would have been tried as a witch. Molland says that like Hill many, if not most, women who were accused of witchcraft were “outside patriarchal control” to varying degrees. I found Molland’s discussion of fear fascinating because it exposes the irony and hypocrisy and misogyny of the witch trials.

Like Anita Hill, women who stepped out of their narrow lane are treated like they could be the new Eve and trigger the downfall of civilization. How could patriarchy be so deeply woven into human history and yet become so fragile that one woman could jeopardize it? Superstition was certainly more prevalent centuries ago than it is today, but I believe the fear of witches was not a fear of the cauldron stirring hag, but of adult women as individuals.

Molland quotes the Malleus Maleficarum and Sigmund Freud; one from 15th century Germany and the other from 20th century, Austria. From the former “a woman who thinks alone, thinks evil.” From the latter “a strong woman is a castrating woman.” A slight shift in supernaturalism to atheism, but the sexism runs through virtually unchanged. The quotes echo one another and their disapproval of independent, strong, intelligent women. A disapproval that Molland would suggest is fear under a very patronizing disguise.

I’d like to mention a couple of things before I wrap up the episode, again, I’d like to acknowledge the validity of witchcraft in terms of herbalism, rituals, and spirituality (those that of course do not harm anyone or anything). And while this episode has highlighted the unpleasant aspects of this history, remember that gory punishments and stereotyping of women as hags was specifically meant to demonize these women. I think it’s important to remember who or what is being criticized here. It’s not the old ladies with the herbs or cool modern witches; it’s the individual men and patriarchal system that have historically punished these women. Also, it was pointed out to me by one of the podcasts, wonderful editors that only one of my five sources was written by a woman. I wouldn’t read too heavily into that (partly because I don’t think it was my subconscious bias because I literally thought one of the authors was a woman until I was corrected) but I do think it’s interesting that most texts written on the subject are still by men.

I’d like to thank my mom and everyone who has been working on Seasons One and Two, and all of you for listening for helping to further our understanding of history. Especially through this research, storytelling, and these discussions, I have much more optimism for the future of women and marginalized voices.

PART TWO.

D’Vorah Grenn

In this talk, I want to address the questions core to the Breaking Down Patriarchy podcast: Does structural patriarchy still exist in our world? How does it affect human life? I’ll begin by stating the obvious: We are enveloped in the damaging structures and language of a patriarchal culture. It is insidious, often almost invisible, constant and has far-reaching effects on our thinking and so also affects both our conscious and subconscious lives.

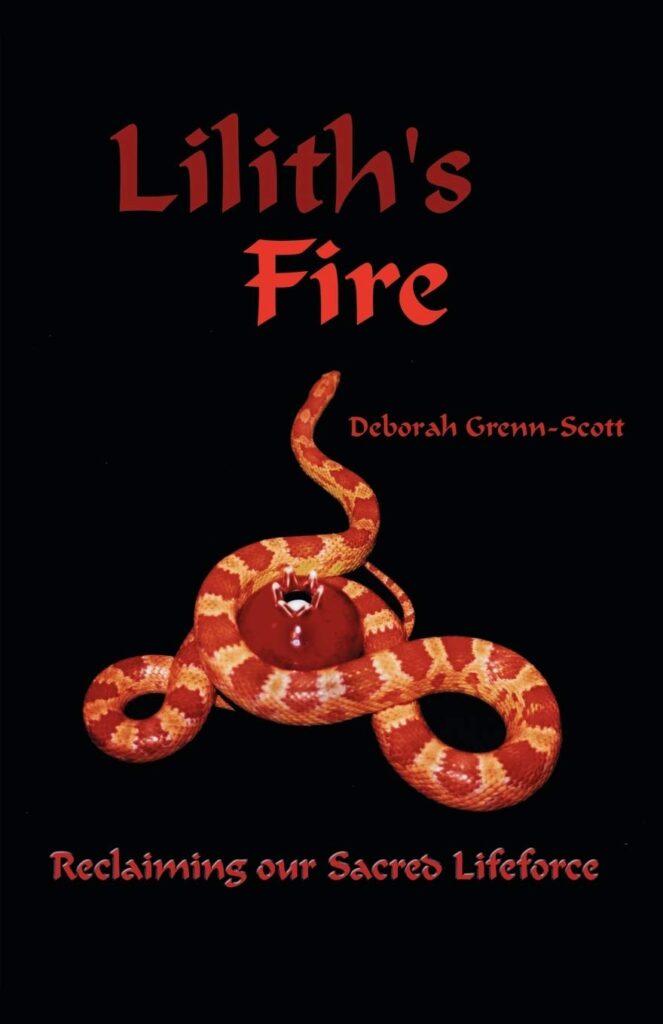

I recently wondered about these effects — although of course I read, talk and teach about them every day — for a piece I was writing. Patriarchy is a toxic thread that runs throughout and underneath all our social, cultural, political and religious institutions and systems. Anyone who listens to this podcast or watches the news knows that—or at least has the evidence of it in front of them, if they haven’t yet recognized it for what it is. It runs throughout our consciousness and informs most of our decisions until we wake up from what Monica Rodgers of The Revelation Project calls ‘The Trance’, or what I termed as a collective coma in my own book, Lilith’s Fire. The essay I was writing as I was thinking about this, however, was for Girl God Books’ Re-Membering with Goddess on the patriarchy’s perpetuation of trauma, and I wrote: “When did I begin to pray freely, openly, unencumbered, unafraid, un-self-conscious, without shards and shreds of imposed guilt and patriarchy running through my consciousness?”

What did I mean by that? As examples, the guilt and shame that a male-dominated, male-directed system instills and constantly reinforces to silence our voices, take away our choices and shut down our ideas. A socially constructed system that insists beauty and sexuality be defined only one way, in ways that fit the status quo and don’t rock the proverbial boat.

When I started hearing about the female face of G’d, that there was, as Patricia Lynn Reilly wrote, A God Who Looks Like Me, She became an organizing principle, and more: my very lifeblood, a vital affirmation of all the things I was and am. I only started to realize in my 40’s how many parts of me were never allowed to surface, never given support or encouragement because of the imposition of patriarchal values, mores, expectations.

We are enveloped in the damaging structures and language of a patriarchal culture. It is insidious, often almost invisible, constant and has far-reaching effects…

These values were all too alive during my marriage. After my husband died in ’91, I began to examine what parts of me had been slowly stripped away or killed off with great intent, parts that could return once I was free and on my own. When I first learned about Lilith, the first woman created before Eve, according to Jewish folklore, I realized with great delight we had a lot in common. She was a free spirit whose mate dominated her, a sexual being whose desires were suppressed. At one point she’d had enough, and left (something I was never able to do). She flew out of the Garden of Eden for the shores of the Red Sea because, as Aviva Cantor wrote in Lilith Magazine in the ‘70s, “for Lilith Eden was more prison than Paradise.”

Some versions of this story say that she was thrown out of the Garden, but that’s not the version I am most familiar with. I will now talk about G’d sending angels after her: when she’d had enough and flew out of the Garden of Eden, Adam was lonely and complained to G’d. And so G’d sent three angels — Senoy, Sansenoy and Semangelof — after her and told her she must return to the Garden. She refused. They argued back and forth and they said “if you don’t return, either you will be barren or you will have demon children or one hundred of your children will die every night.” So, the deal she finally struck was that if people put an amulet with her name on it at a crib, near a pregnant woman, on a newborn, then she would spare that child, she would not make them sick. And we see evidence of this in amulets around the world — in the Middle East especially, but around the world — where you hear about the ‘evil eye’ and you see amulets, that’s often very connected to the fear of Lilith and the harm she might or might not do. But she is not a demon for many people, and I’ll talk about that in a bit.

A socially constructed system that insists beauty and sexuality be defined only one way, in ways that fit the status quo and don’t rock the proverbial boat.

To delve deeper into this idea of the female face of G’d, to explore my relationship to Her and to myself, I’d like to now read a few excerpts from my book Lilith’s Fire.

Several people said that the title of my book, Lilith’s Fire: Reclaiming our Sacred Lifeforce was perhaps a bit overused, but I felt no choice. Every cell in my body was calling me to reclaim my own sacred lifeforce, since I had just started identifying it — how could I not encourage other women to do the same? How could I deny them the same awakening, or not let them know they were sacred too, and that seeing themselves this way was a path to self-authorization, to agency, to a way away from living a male-constructed life?

The book focused on Lilith and drew on her as both role model and symbol. I examined why and how modern women are often demonized — identified as “bad” for actions perceived as reasonable for men, or simply by virtue of being female — through the same techniques used to silence our foremothers. I also investigated how contemporary women had started to reverse the effects of this demonization by redefining for themselves what is right and wrong.

In so doing, I tried to counter existing myths and raise new questions about behavior usually classified by our society as sinful or shameful. I’m talking here about women not being allowed to be fully sexual in situations where a man would be cheered on and called a stud; or when women are shamed for being independent decision-makers without consulting a man. Women are shamed for being too heavy or too thin, wearing too much or not enough makeup, for speaking our minds clearly and firmly without being careful not to offend men’s fragile egos, for moving ahead with the same determination as a man in a corporate career, and especially if they decide not to have children. We are still caught in the double standard, the Madonna-Whore Complex. It’s my hope that through reading my words, people will come to see how urgent it is for us to work together to change a system that equates sex with sin, things erotic with things pornographic or violent.

From the book:

As a basis for the discussion, I draw on the work of women who provide strong models for a more proud, sensual, confident way of being than that espoused by Western social and religious structures.

‘Sacred’ texts, art, mythological tales and writings, oral traditions, and ritual objects such as amulets have been among the primary vehicles used to demonize Lilith from ancient times through the Middle Ages and even today. (She started out as a goddess, who some feel was called on for protection during pregnancy or a hard or failed labor at childbirth).

Demonization, an insidious technique at best, is an effective literary, religious and social weapon, a subtle tool of social control and psychological manipulation often wielded with such dexterity as to be invisible to the very people bound by it. I think it is important to also look at current uses of this weapon in the modern workplace, in religious structures, within families and in our own neighborhoods.

I refer, for instance, to those things which are deeply disturbing but are still embedded in this society and therefore taken as ‘normal’, such as ads and movies which characterize sexually healthy women as sluts, and oral or written texts which accuse independent women of a variety of mental health problems from nymphomania to paranoia.

Ancient and modern societies have used the tactic of demonization for its effectiveness in controlling, manipulating, exploiting and dividing girls and women to keep them powerless, to keep us from uniting, pitting Lilith against Eve, “good girl” against “bad girl”; its equal efficacy as a tool of keeping one group, religion, or political party dominant over another…

To step away from the book for a moment and discuss a modern day example: We see this same demonization when the press, the public, or other politicians go after women like Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, women who are smart and confident, who speak their mind, who work in the forefront, often a dangerous place, but sometimes the only place to make significant, positive social change — and to inspire others to follow suit. In her case, the demonization has gone so far off the rails, so far beyond that characterization as to be criminal, as in the recent image depicting her murder that only two Republicans in Congress had the guts to protest — something that should result in the Representative in question being thrown unceremoniously out of Congress and charged with a crime.

Throughout my work, I understand the term “demonization” to be almost synonymous with, and certainly created by patriarchy

In a related story, it’s hard not to also mention the fact that those who participated in the January 6th attack against the Capitol committed treasonous acts which should have resulted in both expulsion from Congress and legal punishments. In that whole scenario, we see the support and protection patriarchy provides, and some of the ways in which it intersects with and supports white supremacy, racism, homophobia, anti-Semitism and certainly misogyny, the hatred of women.

Back to the book:

Demonization has also been used for:

– satisfying the human need to explain frightening or tragic events through the use of myth or symbol;

– rationalizing a mistrust of those who go their own way, those who (like Lilith or AOC, both mythological and human figures) are ‘too independent’ or risk being in the vanguard of new movements — and as a means of keeping them ‘in their place’;

– as a response to the jealousies and insecurities that lead to suspicion, fear of loss and ultimately the passing of moral and legal judgments on one’s peers or perceived inferiors. This was illustrated in the extreme by the witch hunts of the Middle Ages, when healers were accused of being witches simply for growing herbs or performing the functions of a midwife; witch hunts continue today in many modified forms which may not always end lives but surely ruin them.

Often there are not modified forms, but brutal murders as are carried out in Tanzania and other parts of the world. Like in parts of Africa where elder women whose eyes are heavily bloodshot so as to appear red are killed or maimed with an axe (when, in fact, the redness comes from cooking over steaming cauldron inside a hut, for hours sometimes). And these are not isolated incidents. We read of similar stories, where women are stoned for actions for which men might simply receive a slap on the wrist, if there is any acknowledgment of wrongdoing at all.

I hope to help bring about a greater understanding that portrayals of mythical or real women as innately evil undermine the self-confidence of all women, and in turn their ability to take risks, assume leadership or claim power, from bedroom to boardroom.

As I move through this work, I look at the ‘power over’ systems first named by Starhawk (1982), and examine the use, rationale and soul-killing effects of behaviors sanctioned by the dominator model we inherited (Eisler, 1987). “Power over” is the dynamic in which one person believes themselves to be superior to another and so creates this unequal power dynamic, as opposed to “power with” another. I share the beliefs expressed by Starhawk, Eisler, and many others that the psychological patterns of domination and submission created by this model and played out daily — at home, in the workplace, within our legal system, and in relationships — distort what is beautiful, create artificial constraints and dis-color our perceptions of natural life processes.

As I prepared for this podcast, I found myself waking up one day thinking about all the times and ways I have been and am Lilith!

I was Lilith when I curled my full body of hair at age 10 or 11, had a natural curiosity about how babies were made, and probably listened with fascination to Mom’s menstruation explanation at 11. I was very acutely aware of her discomfort, as I was when I asked my Dad how babies were made and noted his discomfort as he took me to Mom so they could both tell me about the ‘birds and the bees’. I especially was Lilith when I was caught with a ballet case full of cigarettes as I prepared to go to camp one year and withstood the hyper-watchful, critical eyes of my aunt. I think it was doing something forbidden which gave me joy — not the actual smoking — but the rebelliousness of the act.

In retrospect, I recognize the sexual side of Lilith in myself as I look at the time I was accused of dressing like a ‘tramp’ because I wanted to wear ski pants in public! I wasn’t allowed to because they were, of course, skintight and in flaming orange. These pants were not even remotely as tight as today’s leggings!

In seventh grade, I wore a skirt deemed much too short by the school Administration and my mother was called to drop what she was doing and bring me a longer, “more appropriate” skirt. Whether she approved of my outfit that day or just didn’t notice how I left the house I have no idea.

I was definitely Lilith in junior college as I defended myself when my mother called me a slut on finding out I was dating two boys at the same time. She was in menopause and clearly angry, and I met her accusation with outrage, but possibly with a modicum of shame as well — a common manifestation of a patriarchal culture. Although I didn’t find anything wrong with my own desires, her judgment was a hard pill to swallow at the time and a wound that probably took 20+ years to heal.

I was left in my sexual curiosity at age 17 when I was trying to decide whether or not to have sex for the first time. I asked my father if he had had sex before he got married. He looked at me amused, knowing why I was asking and simply smiled and said, “It’s different for a man.” That was definitely not good enough for me, not the answer I wanted to hear nor the permission I had hoped for. The ‘slut’ accusation and the idea of only men being allowed to have premarital sex certainly result from the ongoing double standard created by patriarchy.

patterns of domination and submission created by this model and played out daily..distort what is beautiful, create artificial constraints and dis-color our perceptions of natural life processes.

I had Lilith’s conviction about my own values, and then outrage, when I was fired from a job tending bar at a “go-go” club — what today would probably be called a strip club —because I wouldn’t sleep with one of the bosses.

I had Lilith’s curiosity and spirit when I left the suburbs of California for the wilds of Manhattan. I fled in search of freedom, to get out from under my parents’ roof, to be able to make my own decisions and set my own course. I believed I could conquer the world and felt self-authorized to handle whatever scenarios I walked into. I wasn’t world-smart enough then to fear some of the environments I stepped into. I don’t think fear appeared in my consciousness until an attempted rape in a California hotel bathroom in the early ‘70s.

Women are trained to have fear in this culture, and with too many good reasons. This is something patriarchy relies on, and it can kill both girls’ and women’s spirits, and so opportunities for growth or development. It is critical that we continue to build a new world, that we continue working to break down patriarchy with as much passion, energy and strength as we can summon so that today’s girls, and boys, have a different, more egalitarian and much less violent life…a world in which rape is never accepted as inevitable, or domestic violence as a “private matter”. A world in which we never hear or use the expression “boys will be boys” to excuse violent behavior. These are among the reasons this podcast is so important.

I think I have always carried Lilith in me ever since and even long before I heard about her. I was always different, often a rebel, angry starting in my later teen years when my choices were not respected and I was under the patriarchal control of a loving though authoritarian father. I wanted to get away, to be my own person, to dress the way I wanted without having to fight my mother to do it, to be supported in my choices as a person and not just as a daughter, a student, or in comparison with a much quieter (and more diplomatic) sister.

I didn’t realize until my 40s that I lived in a patriarchal culture, but certainly reacted male-dominated and directed decisions and policies whenever they appeared. I think the patriarchal culture in its liturgy, in sacred texts, also separated me from my religion of birth, but I didn’t realize that was one of the reasons until much later.

One incident that stands out is when a Manhattan cab driver called me a c*nt and other curses – because he thought I was trying to beat the fare when I told him I had to get out to get change from a store across the street because I didn’t have the right change for the fare. To this day, I pride myself on having taken him to the Taxi and Limousine Commission for a hearing to report his disgusting behavior. It was inconvenient and cost me at least half a day, but I felt very vindicated when he was fined $25. Though they didn’t feel like big enough punishments. I had sought and achieved a modicum of justice, so the amount didn’t matter.

I embodied Lilith’s spirit when I took off with a girlfriend to hitchhike down the California coast, when I starred in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” at my college – having the chutzpah at 19 to play Martha, a loud, crass, often vicious, and always sexual character once so powerfully portrayed by Elizabeth Taylor.

And perhaps I even was Lilith when I cared nothing about convention, perhaps as some suggested went out of my way to defy it, when I married a Black man in 1975 — although I did marry him out of love. This was apparently considered so outside the fold, unacceptable and radical for many that we could find no one to marry us, until finally we found a liberal rabbi who would perform the ceremony.

By the same token, when we explored Catholic priests, as my late husband had come up Catholic, we were told we could not be married in the usual place in the Church and would not have been considered a sacrament. All these “rules” are male-invented and male-supported, as is the difficulty of leaving an abusive marriage, where in the Catholic Church, one can only do this — unless granted a special exemption such as annulment in the first year of marriage — at the risk of being excommunicated.

I struck the word obey from our marriage vows and was delightfully surprised when the rabbi had us both break the traditional glass under a chuppah, a canopy. That chuppah should have represented a safe home, a kind of Paradise as Lilith supposedly started out in, but the ceremony that happened there led me too into an imprisoned life.

I am Lilith in my desires, in my determination always to be free, to speak my mind, to not put up with constraints, restrictions or someone else’s rules, my impatience with small or narrow minds, in my rebelling against authority, in always feeling an intense pull to explore the world and willing to take risks to do so.

To conclude, I’m going to offer you all a sneak preview of my “Lilith Dialogues”, unpublished writings which I share with you for the first time:

Lilith visited me a few years ago, compassionate, laughing with me, friendly and not angry as I might have expected but at times more hurt, sad almost, pointing out the injustice of having HAD to leave Eden to be free…I wondered whether I could assume that the ‘other’ so-called demons she met at the Red Sea after leaving Eden treated her equally?

[My connection to Lilith] must be part of why I like and can so often relate to the usually dark and angry TV character Jessica Jones. I noticed that she walks, in her jeans, as I so clearly remember doing along a San Francisco beach at age 19…feeling that was my “male” energy (or at least later describing it as such). This image fits well into what Judy Grahn describes as my “out Lilith days” – but not “Out, Lilith!” as is inscribed on many amulets. (Poet and author Judy Grahn, for those who may not yet know her work, was co-founder of the lesbian feminist movement and is a cultural theorist whose work and teaching has greatly influenced my life. I recommend all her writings.)

Me speaking to Lilith: I read that you left Adam after G’d made you together (as in one primal form, as in Lilian Broca’s famous painting). How could you do that? Wasn’t he your other half?

Lilith: Right up until the day that he demanded that I lay under him during sex…I found that rather boring and way too predictable…

Me: In fact, in my own life I don’t like to get bored and I don’t like things that can constantly be predicted. I like a certain amount of stability now that I’m in my 60s but I certainly preferred unpredictable when I was younger. I do still love spontaneity.

But Lilith, they say you left Paradise—I realize it wasn’t Paradise for you…

Lilith: Absolutely not, it was a prison in effect. It started out looking like a Paradise, as many marriages in your time do. Although it started out looking that way, I realized I would much prefer to choose my own company, even if they were called demons (or strange, weird, fringe figures) by the outside world, society, by other people…

Me: I’ve been operating on the fringe…Some of my more radical friends, who in fact are pioneering thinkers might be considered demonic by others today…especially in a culture which lists “sorcery” as a caution in the Motion Picture Association warnings before a movie as innocuous as ‘Fantastic Beasts’!

Lilith: I just thought I’d explore those caves by the Red/Reed Sea! There certainly was an interesting array of people there. But the main thing was that I felt free. It was probably kind of like you escaping the California suburb in pursuit of an acting career in Manhattan.

Me: That’s true. I couldn’t WAIT to get out of the suburbs and was thrilled to be in the Big City, the Big Apple, a place where the nights held great intrigue and mystery and attraction for me, so much so that one of the first things I did was to start working in a midtown bar at night. Of course, it was part of the social life and it was part of the social life of many young people now, at least pre-COVID…. I went there late in my 20th year and had my 21st birthday there. It was pretty lonely and I remember being homesick (at least for a day or two). But I was free.

How could patriarchy be so deeply woven into human history

and yet become so fragile that one woman could jeopardize it?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!