“my life is an open closet”

Amy is joined by storyteller and founder of The Trevor Project, Celeste Lecesne, to discuss his incredible life of acting and activism, plus how a story can save a life, and exciting new ways our world is changing for (and thanks to) queer youth.

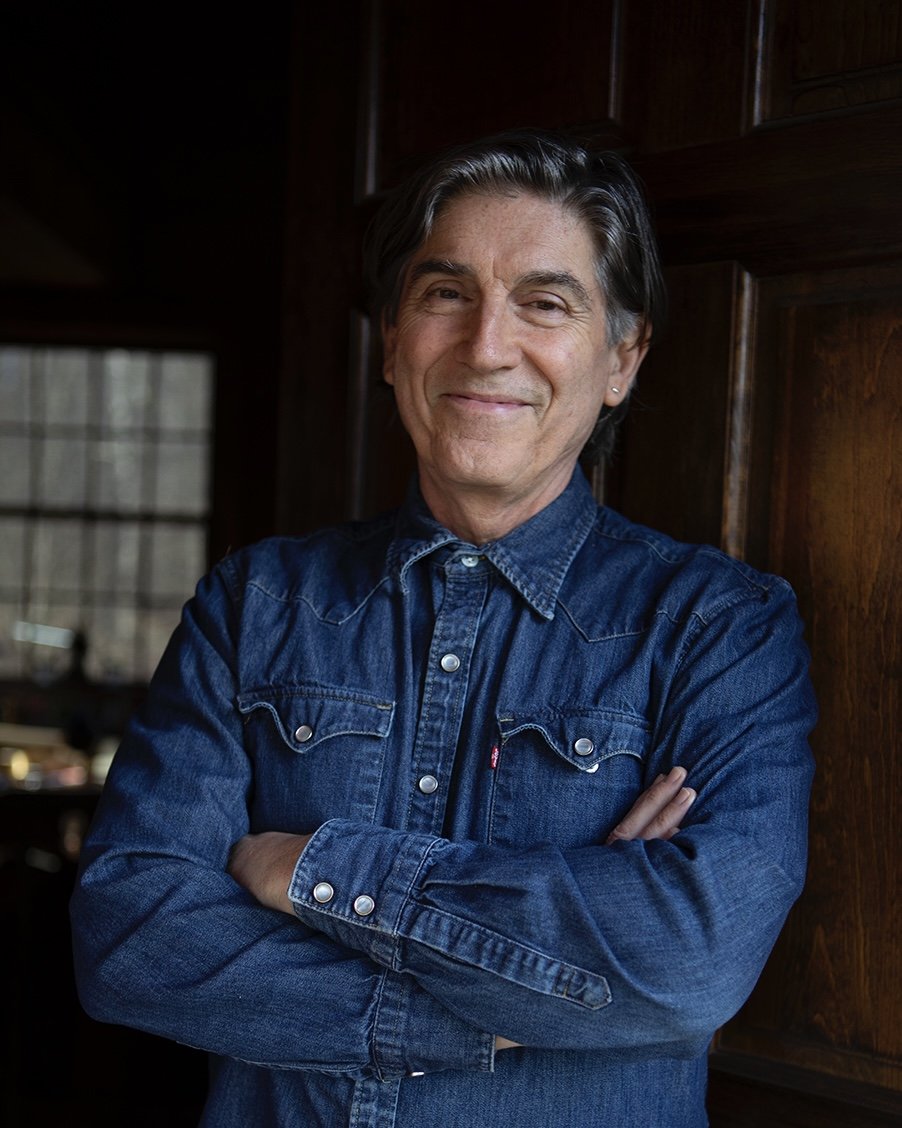

Our Guest

Celeste Lecesne

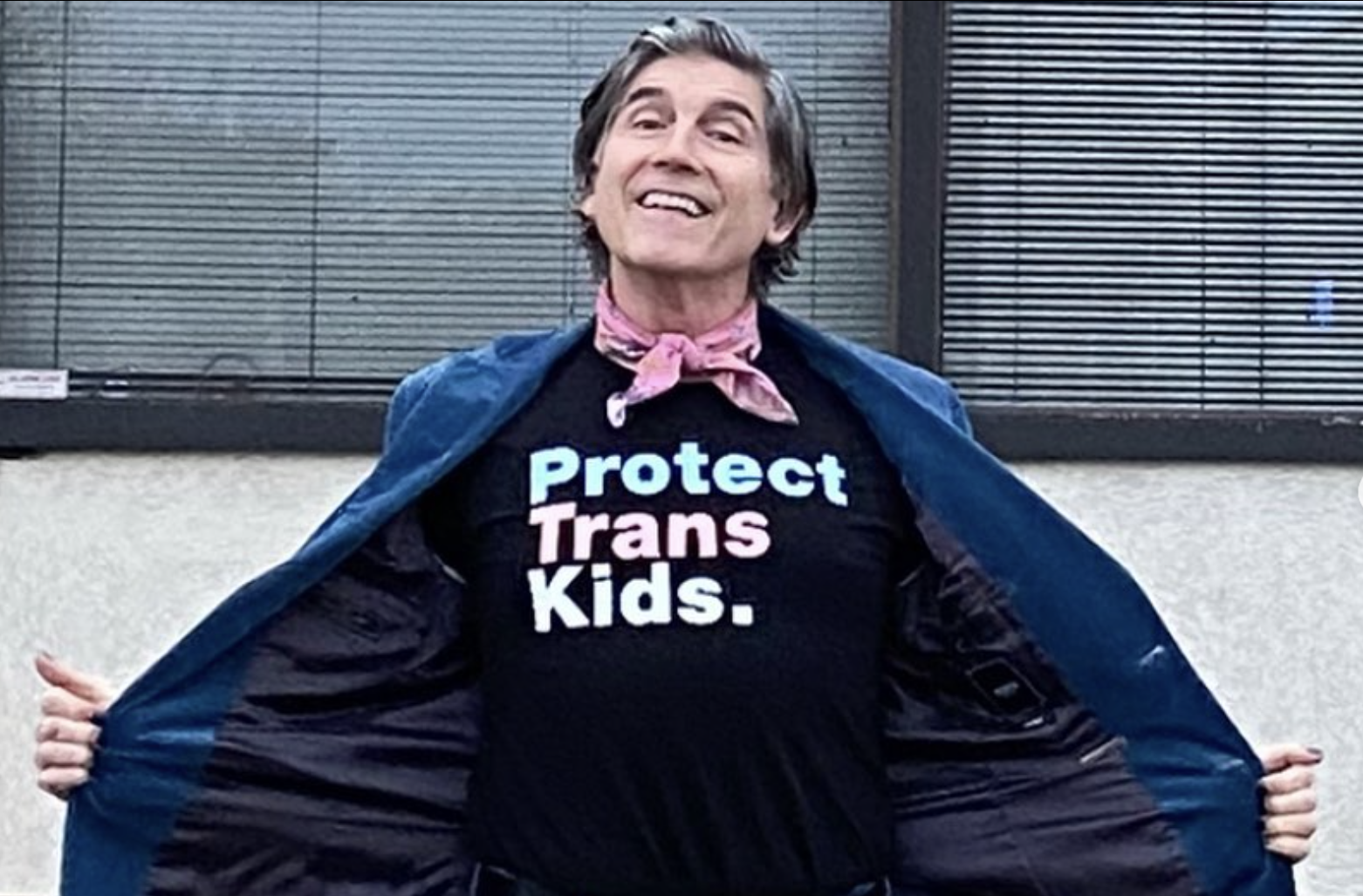

James Celeste Lecesne is an American actor, author, screenwriter, and LGBT rights activist, best known for the Academy Award winning short film ‘Trevor’. Lecesne has written several books, including Absolute Brightness and Virgin Territory, and is also active in the entertainment industry as an actor and producer. In 1998 Lecesne co-founded The Trevor Project, a nonprofit focused on suicide prevention for LGBT youth.

The Discussion

AA: As listeners may know, I grew up in the 80s and 90s in a household and community that was very deeply religious, very deeply patriarchal, and very deeply heteronormative and homophobic. I didn’t know the words ‘heteronormative’ or ‘homophobic’ as I grew up, but the message I absorbed was that it was simply a given that everyone was comfortable in their gender identity and everyone was straight. I was taught that to deviate from that at all was a very, very bad thing. And to my great sorrow, as I look back, I didn’t develop a critique of that system or even empathy for people who are struggling inside that system until I was much, much older.

So, how did I finally begin to wake up to the reality of so many of my fellow human beings? Partly, I began to wake up through people I know being brave enough to share their stories with me. And partly through some online initiatives that opened my mind and heart—one of these was the Trevor Project. Simply knowing that there was a helpline for LGBTQ folks forced me to confront the fact that queer folks needed help. which was the beginning of a growing awareness that queer youth, especially, needed help, not because there was anything wrong with them, but because there was something wrong with our society.

So I am deeply honored to be welcoming today the founder of The Trevor Project, James Celeste Lecesne.

Welcome, Celeste. I’m so excited to have you here today.

CL: I’m so thrilled to be with you, Amy. Thank you for having me.

AA: Thank you for being here. As usual, I’m going to introduce you with a tiny little professional biography, and then I’ll let you get into all of the wonderful details of your life.

But just to acquaint listeners, James Celeste Lecesne is an American actor, author, screenwriter, and LGBT rights activist, best known for the Academy Award winning short film Trevor. Lecesne has written several books, including Absolute Brightness and Virgin Territory, and is also active in the entertainment industry as an actor and producer.

So again, that’s a tip of the iceberg intro, but Celeste, I am just so honored and thrilled to have you here today. And I wonder if you can start us off by telling a little bit more of your personal story: where you’re from, your family, your education, and the factors from your history that have made you who you are today.

CL: Yeah, well, that might take us a while because there’s a lot of history. But, you know, I grew up in New Jersey, in a little bedroom community not too far from New York City. And I think from a very young age, I was always a very upbeat kid. I was always very creative and even joyful I’d say. And very early on, I realized that I was different from other people in my family and from other people in the world. And part of that was that I realized really early that I was queer.

And I think it was the beginning of my consciousness, really, was to understand how I was not like the people in my family or the people in my community. And of course I didn’t tell people. I didn’t know what it was. I had no indication in those days that anything existed other than heteronormativity. And it didn’t frighten me. I actually loved who I was. But at a certain point, I think I began to understand that my parents were disappointed at it. Of course they loved me as they do, you know, as parents do, but there was a certain level of disgust as I began to show signs of not really fitting in and not being what they had expected. And it was never said. They never expressed it except by a certain withholding of their approval and their love, which was really a tough thing to be able to bear as a young person without anybody to talk to about it. And then… I could go into the whole thing about my childhood, but I think the important part is that without my parents not accepting me for who I was and who I am, I would not have had the ability to do all that I do and did in the world.

And most significantly, yeah, I wrote the Academy Award winning short film Trevor, but I think more significantly I’m the co-founder of The Trevor Project which is the largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention lifeline in the world for LGBT and questioning young people. And I think without my parents, that would not have happened because Trevor…though Trevor has a different name than I do, it’s a fictionalized account of my story. And what happened to really jump far ahead is I grew up, I got out of my house as soon as I could possibly get out of there. Actually, I left a couple of times before it was a good idea to go. And then I would come back and then I finally left. And I made my way to New York and I became, you know, a writer and an actor. I’m a storyteller. And at some point in my New York life, I was confronted with the AIDS crisis. And what happened was that I was surrounded by people my age, friends, colleagues, who were dying in alarming numbers.

I know we just jumped into this very quickly, but I was really there on the front lines of this epidemic and this disaster, and it seemed like nobody cared. It just seemed like the community was having to deal with it ourselves. And at the same time, I heard a radio report on NPR about the suicide rates among young people. And they just, at the end of it, just casually mentioned that a third of the suicide attempts that they knew of were attributable to, at that time, gay and lesbian young people. And I thought, this is insane. Like, here’s this one generation that is dying and nobody cares. And here’s this other generation, three to four times more likely to attempt suicide than their heterosexual peers who are choosing to die. And I was like, this is insane. It just, it filled me with a kind of rage and out of that rage—at the time I was writing a solo show that I did off Broadway and I’d perform and play all these different characters and there are many stories in the show and one of the stories I wrote was really an autobiographical inspired show about me when I was 13 and my attempt to take my life.

Like I said, I grew up in a world in which homosexuality was a crime. That’s what it was when I was a young person. That’s the world I grew up in. It was a sin, and it was a mental disease. These were on the books, right? And I just thought that was crazy as a young person.

AA: You already knew? Did you ever doubt? Did you ever absorb like “it’s a crime?” Or did you…

CL: Of course! I knew I wasn’t a criminal. I knew I wasn’t crazy like that, and I knew my spirit. I knew I wasn’t a sinner. I just knew it. I don’t care what anybody said; I was not those three things. They could have that idea, but that was not me. And I don’t think I escaped the harm that those thoughts, that the world wants you dead and disappeared like… how do you grow up in an environment like that and not feel it? What I felt was there was no place for me in the world. I was going to grow up into a world and I had no future. That was the hard part to bear. Not that I was bad, but that there was no place for me.

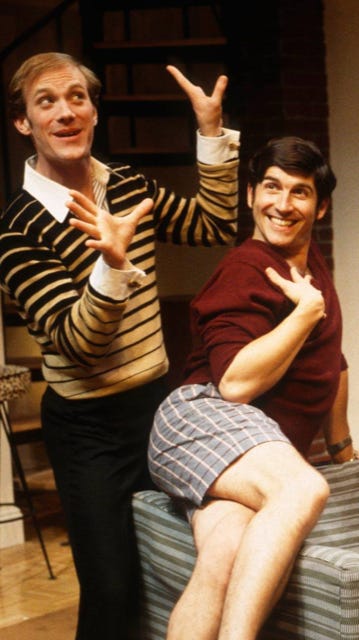

So I was able to actually go back into that experience when I was between 30 and 40 years old and write a piece that I performed on stage. It was only 10 minutes on stage in which I played this 13-year-old boy named Trevor, who through a series of diary entries realizes that he’s gay and decides that he is going to end his life, but doesn’t go through with it. And it’s really, you know, it’s a beautiful story. It’s funny, it’s poignant. And I performed that as part of a larger show that I did off Broadway.

And then Peggy Rajski, a filmmaker and her producing partner, Randy Stone came and saw the show and then reached out to me and asked me if I would adapt it as a screenplay and Peggy directed it and produced it and Randy produced it and the film came out and, incredibly, it won an Academy Award. It’s such a huge turning point in my life because the film was about 15 minutes long and what I got to see was how powerful a story could be. That this 15-minute story that came from the depths of my life touched the depths of other people’s lives. And it had happened at just the moment in the culture when people were ready to consider an alternative to suicide for young people.

AA: What year was that, Celeste?

CL: I started performing the show in 1990. And the film came out in 1994-95. And then in 1998, we made arrangements to put it on HBO. And that was exciting. But of course, Randy, Peggy, and I thought… Okay, well, it’s going to be in people’s living rooms and there are going to be young people watching it. So maybe we should do the responsible thing and put a telephone number at the end of the film. And of course there was no suicide prevention lifeline specifically for queer young people.

We raised the money. We trained people to do it. We partnered with an already existing lifeline. And that first night over 1400 telephone calls came in from young people around the country. Not all of them queer, not all of them suicidal. But each one of them represented somebody who understood what it felt like to feel different. And that was the next turning point that I had in my life, which was to understand that a story could go out and actually save a life. It could actually do something impossibly beautiful, right? So much more powerful than just getting an Academy Award, which, you know, it’s not a bad thing either, but it’s not saving a life. So, again, going back to my parents…without them, I never would have been able to tell that story, right?

AA: Because it created the heartbreak that sometimes is what fuels art.

CL: Yeah. You know, a friend of mine, beautiful V, who is my dearest friend, she’s also formerly Eve Ensler. She wrote The Vagina Monologues.

AA: Oh yeah.

CL: She said a beautiful thing once, which is that we give the thing we need the most to heal the broken parts inside us.

That’s the world I grew up in. It was a sin, and it was a mental disease.

So we made it.

And, you know, in that case I think Trevor was a really good example of that. I was able to give something that I needed, which was A. representation and B. somebody to listen. Just somebody out there who could listen, which I believe is the secret sauce to love, is just listening. Right?

AA: It is. I believe that. I think that is love for me. To have someone sit with you as a witness, with compassion, and just listen to your story, I think that that is love for me.

Okay, I have some personal questions, and you can decline if you don’t want to answer them, but…

CL: Another thing I always used to say was, “my life is an open closet.”

AA: I love it.

CL: Always has been.

AA: Okay. Well, I’m just wondering, and I mean, I appreciate that phenomenon that is true that a lot of art does come from pain and does come from grief and I’m grateful for the work that you put out into the world while, at the same time, really grieving that you did have to go through that.

I’m wondering if your parents were able to ever see the work that you were producing and kind of understand what you were doing? And actually, before that, I’m wondering too—because the homophobia that I have worked to dismantle, that came specifically from a religion because I was raised in such a conservative homophobic religion, but I know it’s not exclusive to religion. Was that a part of your upbringing at all or was it just society’s general homophobia?

CL: In answer to your first question, sadly, no, my parents never really came around. I think my mother, God bless her, said “I’m never going to be able to accept this, and I’m never going to change,” is what she told me. And she stayed true to her word. She never changed. My father, I think, was more mournful about it. It made him sad, but he never could get to the point of celebrating me and that was their own limitation. I’d like to say it was inspired by Catholicism—which is what they were, they were Catholics and I was raised a Catholic—but I think it was deeper than that. They truly could not embrace me. They couldn’t embrace me.

And, you know, for me, I was so shocked when I came to fully understand that the church didn’t want me around, and thought I was evil, or at the very least I was damned, right? I just couldn’t believe it because that was not my relationship with Jesus. That was not my relationship with spirit. Like I was good. I was good to go, right? I was thinking about this the other day. I think one of the reasons I love, so much, these young people that I work with now in this current generation is they’ve taught me that your gender is your…it’s your experience. Nobody can decide what your gender is. Nobody has, they don’t have reach into that. They can’t tell you, nobody can tell you what your sexuality is. Nobody can get you to be gay. Nobody can get you to be pansexual or whatever. You decide that. That’s between you and your body and yourself to know what moves you.

Really, just last week, I thought to myself, Oh, and this is also true of faith. No one can stand between you and what you believe. People can hold a gun to your head and it does not change the depths, it can’t reach what you hold in your heart. It’s unknowable to anybody else. So I feel very fortunate that very early on I had a deep connection with something that I would call spirit, that allowed me to get through. It allowed me to get through whatever difficulties and harms were all around me telling me that I was worthless. It was hard, no doubt about it. But I think it’s the kind of thing that if you can get through it, then you go out and help other people.

AA: Oh, that’s beautiful. And that brings us now back to The Trevor Project, so I’d love to pick up there again.

You produced the play and then the movie. And then it was, you said, picked up by, did you say HBO? So it was broadcast in people’s homes. And that’s so fascinating, that it was just kind of this organic realization of like…Oh my gosh, we could help people if it’s going to be in their living rooms. Let’s put a phone number. Oh, a phone number to where? How are we going to help them? That’s just incredible. So how did you go from that to The Trevor Project?

CL: It really happened right away because we had to become a nonprofit. We had the date to air the film on HBO. Bless Peggy Rajski, she did all of the paperwork. Bless me, I raised all the money. And bless Randy, who set us up at HBO. So together we were the team that had different areas of expertise. But we had to really hustle. We had to make it happen because we had the air date on HBO. We also had the good fortune to have Ellen DeGeneres, who had just come out—this was 1998—she agreed to do the wraparound presentation for the film, which meant that everybody was going to see it. Right? It was going to be a cultural event. Because she hadn’t done anything since she had come out, and suddenly she was doing this amazing thing, God bless her.

And then the first few years of The Trevor Project were tough. They were tough. We had to figure out what it was, how to do it. But we were always very clear about one thing—which I really love—which was: we made a decision that we would be really good at one thing. And that one thing was listening to young people. So whatever else The Trevor Project became in later years…Trevor Text, Trevor Chat, Trevor Space (which is like a sort of Facebook for queer youth, where they can go) and as an advocate for queer youth in the government, for doing research about all those things…they came later. But really, the first 10 years, it was really about sticking to that one thing, which was we pick up the telephone, we’re there 24/7 listening to these young people.

And really got to see the culture change as a result, because what it did was it raised up a couple of generations of young people who knew that in the story of being an LGBTQ+ young person, there was another ending to that story. That story didn’t have to end in sadness or suicide. It could also end in community and communication. That was an alternative ending to a story that was, to me, untenable. And I think this is one of the beautiful things about storytelling that can sometimes happen, which is that you put a story out into the world, and it inspires an alternative ending to a story that is unbearable.

And to see the culture change as a result of having that story in it is one of the greatest miracles of my life. I mean, I just get really choked up just thinking about it, which is to be anywhere and have a young person come up to me, and I can see it in their eyes, what they’re about to say, it’s a very particular look. And they look at me, and I look at them, and then they come close and they whisper in my ear, “Thank you for The Trevor Project. I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Trevor.” And I think that’s a miracle. That’s a miracle.

AA: Well, it’s a miracle and it was created by you taking the initiative to do it. I mean, I just think like… what more meaningful work can a person do with their lives than taking, again, the circumstances of your life and then willing and working toward this project and this organization that is now literally saving other people’s lives. I mean, I’m just, yeah….

CL: I know this is about me, but I just want to ask you: you’re so passionate about this topic of patriarchy and breaking down the patriarchy. And I’m wondering how that happened. How for you personally, that you’re so passionate about turning people on to this paradigm that’s out there that is harming us all. I just wonder how that happened for you?

AA: Well, similarly, I mean, pain points—not even close to be honest, I am being sincere in this, it’s not even close to what you experienced in terms of the real harmful animus toward queer folks. I didn’t grow up in a dangerously misogynistic environment, so it was a benevolent patriarchy, so I’m not making a comparison in terms of intensity and severity of the harm. But just the little cuts and also just the cognitive dissonance throughout my life of like… I’m being told that this is either neutral or good or it doesn’t exist, but it feels like it does and it feels like it’s bad. But just the constant pain points of it just wouldn’t… I just couldn’t accept it. You know, I would try. Like you said about trying to force yourself to believe something, trying to force yourself to be okay with something when your mind and your heart knows it’s not okay. And so finally just going like, Okay, I’m going to learn about this and it just I have to really face what it really is.

I will say where our stories kind of intersect with each other is like, I approached the patriarchy project at first because of my own pain points. But what I discovered as I started to read and as I started to talk with other people—and this wasn’t entirely new to me, but it really started showing me like a mirror, the ways that I’m privileged also, and the ways that I have been part of a system and an organization that is so, racist and homophobic. And I mean, I have a podcast episode about my journey as a Mormon woman and with Prop 8 in California and really having to confront that. That was a huge thing for me. So one of the most meaningful parts of Breaking Down Patriarchy for me has been realizing how patriarchy intersects with other oppressive systems and realizing how privileged I am.

And now it’s not really about me anymore. It’s about, oh my gosh, women also oppress other people. Straight women oppress queer women and white women oppress women of color. And so it’s just so much bigger, so much bigger than that. And realizing that has been profoundly life changing for me.

That story didn’t have to end in sadness or suicide. It could also end in community and communication.

CL: I’m always amazed. In preparation for this podcast with you, I’ve really been thinking about why there isn’t more solidarity between the feminist movement and the queer movement when they’re both really under the thumb of the same oppressive system. Like you say that “it’s not so bad over there.” And I’m like, it looks pretty bad to me.

AA: I mean, it can be, there are ways that it is..

CL: Look, it’s all relative depending on people’s individual experience, but the oppression is oppressive for everybody. It’s there. And I’m always amazed that there’s not more solidarity.

AA: There needs to be, because once you realize… I don’t understand how people can’t have empathy and realize, oh, I know, at least a little bit, I know what it feels like.

This is where things clicked for me. And I’m embarrassed to admit it, I’m embarrassed about how old I was before I started really deconstructing my homophobia. I hadn’t known anyone closely yet who was out. I’m sure I did know gay people, but they weren’t out to me, so I didn’t know. And it took me a while before it like entered my life and I really became aware of it. But I sure did know what it felt like as an LDS woman to have a system with people in power where they had absolutely all of the power of whether they even wanted to listen to me or not, let alone take my voice into consideration, right? And so when gay marriage was being considered and when Prop 8 was happening and then it was in front of the Supreme Court and stuff, it was a lightbulb moment where I was like, Oh my gosh, I’m the one. I’m the straight person that… I remember this gay couple at my kid’s school. And I was like, do they feel when they come up to me and if this topic comes up where I’m allowed to get married and they’re not… When they talk to me, are they feeling the same way that I feel when I talk to a bunch of men and I feel like a little mouse in an arena with a huge guy. And he’s like, maybe I’ll listen to you. Maybe I won’t. You know what I mean? I don’t know if that makes sense, but…

CL: Absolutely, absolutely.

AA: That feeling of like. I know I’m right, and I know this is valid, and you can choose to dismiss me, you can choose to step on me. You have all the power. I’m like, oh my gosh, I am in the position of power here. I don’t know.

CL: Yeah, I agree. You know what’s changed it? Again, I just bring it back to story. I was just thinking that…this is a quote that I keep nearby all the time by a really fierce lesbian activist, amazing Urvashi Vaid who sadly died last year, but she said “I have long believed that what made the LGBT movement irresistible was its honesty. Truth may be unpleasant unpopular and sometimes unbearable to speak but its power is undeniable. Telling the truth about desire was and still remains revolutionary in a world built upon its control and repression.” And it was really a generation of people, my generation of queer people who told their parents, regardless of the consequences, who told their aunts and uncles and their nephews and nieces and their neighbors and their friends and colleagues, who told them the truth. That’s what changed the world.

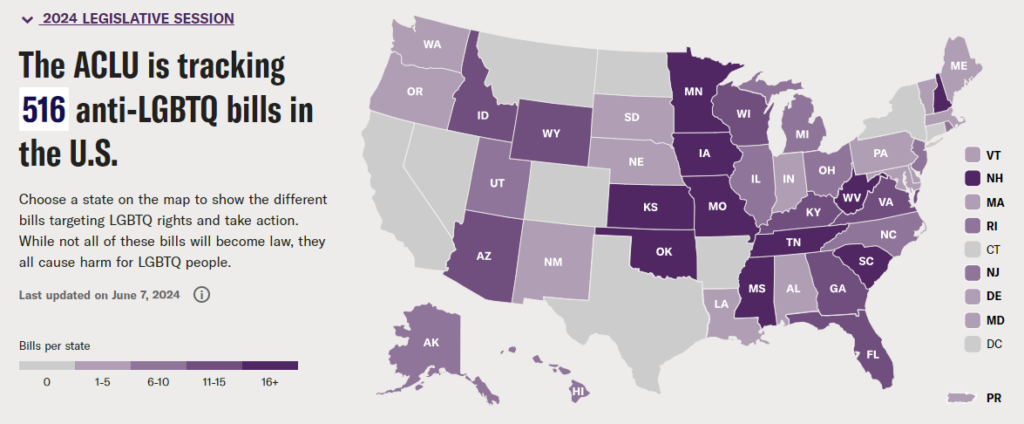

And it’s so painful to me right now to see how hard they’re working to repress a generation of young people and older people from listening to their hearts and listening to their bodies and listening to their spirit. Like, you know, this move towards making this country a Christian country, It’s so frightening to me. Not because I’m against Christianity or have anything against it at all. It’s just, that’s not what everybody believes. And you cannot legislate people’s hearts, or their bodies, or their sex. You just can’t do it. So I feel alarmed at what’s happening right now. I mean, I’m sure you’re aware of the, you know, 540 bills that have been introduced this year alone, since January, trying to really silence and disappear trans and non-binary people especially, but also, really, when it comes down to it, LGBT people and women and trying to restrict their freedom.

AA: Yeah. Yep, for sure.

CL: Not on my watch. Not on my watch.

AA: Good for you. So back to The Trevor project. I want to know, you founded this…this is just kind of blowing my mind. So it was 1998. It’s going strong still. So was there a point that you were really, really involved in it? Like were you kind of the mastermind behind like, here’s what we want to do. Here’s what we want the hotline to be. And then, are you still on the board or how did you kind of shift to the next project?

CL: You know, I was very involved in the early days of fundraising and just trying to keep it going really, to be perfectly honest, you know, as was Peggy and Randy. And in 2015, we had an amazing board. People started really coming on board after about five years and around 2015—so that was 12 years into it—I decided that it was time to make room for other people on the board. I felt like I had, I was on a lot of telephone calls with queer people, but they were all older. And I decided that I didn’t want that to be my life. I actually wanted to be in touch with the young people. So I stepped off the board and I became a lifeline counselor for a few years. And that was how I stayed in touch with the organization. And I just needed to rethink… I mean, The Trevor Project was going strong, but something else was calling me is the only way I can put it.

And so I wrote a show and I started traveling. I did it off Broadway and then I started traveling around the country. And this was like 2015, 2016. And I’d go into schools. I always made sure that I could find my way into a school wherever I traveled or get the theaters that to reach out to schools and bring the young people to the shows. And then I’d meet the young people and I’d say, what school do you go to? And can I come over there and talk to you, listen to you? And I started to hear something I’d never heard before. It was the most extraordinary thing. I’d been working with queer youth for 25 years. Suddenly I was like, Wait. The freshmen and sophomores are talking a whole other language. Wait a minute, what is that? They understood their queer history. They understood they were a part of something that had come before. No generation had ever understood that they were a part of a history. They had a consciousness that people were coming after them. That there were other queer young people that were coming up after them.

That had never happened before. They had realized that they were different when they were in fourth and fifth grade, as opposed to 30 and 40 years old.

AA: Yeah, wow.

CL: They had the internet. They had their phones. which gave them access to the world, which everyone was telling them was bad. And they were like, no, this is great. My friends are over here. This is giving me a window into the world as it might be. And they also had an amazing ability to understand themselves emotionally. They seemed very advanced in that way. And they also had a huge, huge amount of confidence, which I believe is the effect of this little phone being able to get the answer to everything at your fingertips 24 hours a day. It just gave them a kind of confidence that I’d never seen in people so young.

And I became obsessed. I was just like, wait. So I called up my friend, Ryan Amador, who is many, many years younger than I am —an amazing singer, songwriter—and I said to him, I think something’s happening, will you go with me to places like Arkansas, and Alabama, and Indiana, and Iowa, and South Carolina, and places I’ve never been before? And will you go with me and go into these schools and LGBT centers around the country and let’s see if it’s happening everywhere? And, like, just find out, and see if we can document it.

So we did, and we did that for like two years. We would go to a school and stay there and work with the GSA for a week. And we would go on the weekends to LGBT centers and do these workshops with the young people, getting them to sing their songs, write and sing songs, getting them to tell their stories, do true storytelling workshops and really listen to them and what did they know. And what happened for me was that I began to think about myself as a 15-year-old and I thought, Oh, I was uncomfortable because the world I was living with wasn’t my world. I was bumping up against it. It’s taken 50 years for that world to change. So maybe I was living in a future that hadn’t yet arrived.

And so then I looked at these young people and I thought, Oh, wait, they’re living in a future that hasn’t yet arrived. So I would tell them that. And then I would ask them, what do you know? Where are you bumping up against this world? Where do you feel things need to change? And there was a beautiful moment, there’s always a beautiful moment when you actually position a young person at the center of their own story. When they wake up to understanding that they are on the precipice of something brand new, and they kind of blink, and then they tell you. They tell you what needs to change, and often have ideas about how to make it change. It was really a beautiful experience, and then we started The Future Perfect Project because we really believe that the self-expression of LGBTQ+ youth—and I like the word queer because it’s not about who you’re having sex with, it’s not about how you identify as your gender, it’s how you feel in opposition to the culture. It’s how you feel like you don’t quite fit in. You feel queer, right? And it allows for young people to have access to the queer community without having to identify because you don’t know maybe.

But what happened was that we really believe that their self-expression is a declaration of a better future for everybody. Because where they’re safe, where they’re seen, and where they’re celebrated, everybody’s doing better. Everyone’s doing better. And statistics have shown that environments in which they feel free to be themselves, and my experience has taught me, where they feel free to express themselves, everybody feels better. Everybody feels free. We don’t want anybody to feel better than anybody. We want feel everybody to feel the best that they can feel.

So we started The Future Perfect Project and then started getting other people on board, other facilitators and artists who were interested in doing this and then the pandemic hit.

AA: Oh, okay. First, really quickly, before we go to the pandemic, let’s talk a little bit more about what The Future Perfect Project actually does. I was looking at the website, and it seems like it really encourages a lot of art and just expression. Can you tell us just like all the different branches of what The Future Perfect Project does?

CL: Yeah, and it does relate to the pandemic in the sense that up until then, we were traveling around and doing these cozy little workshops all over the country, right? And then suddenly we moved everything online.

AA: Okay. Yeah.

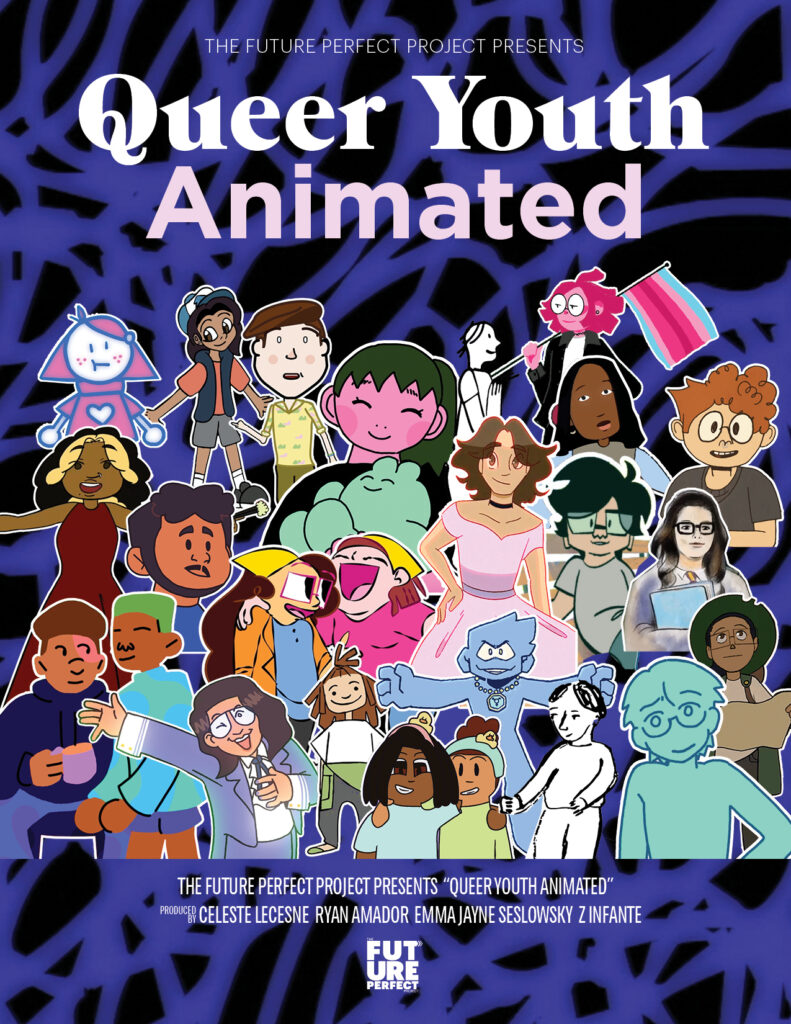

CL: And we thought, Oh, we’re not going anywhere. We’re not spending this money that we have. And maybe what we should do is turn other people on to how amazing these young people are by making content, by making media content, by becoming not only a production company, but like a broadcasting unit in whatever way we can. So we would interview young people about their experience and then edit it down to a two minute interview with an animator who identifies in the same way that they do and have them make a two minute animation in which they get to tell their story. Or work with a group of twelve young people who come up with an idea for an album and each of them write a song. We pair them up with a producer in their bedrooms where they record their songs and then we make an album. We release the album and we bring them to New York City where they meet each other for the first time. And they performed at Lincoln Center. We just released a podcast last month; we just completed our first season of six episodes in which they came up with the title, the theme song, all the segments. It’s really them. It’s really giving them the mic. And empowering them to tell us who they are.

Because, as we were just talking about before, so many people are saying so many things about them. And they do not have the agency or the space to be able to express themselves. And I truly believe that if people heard from them, and heard how happy they are, how joyful they are to be themselves, nobody in their right mind would deny a young person that. The right to be happy. And that just comes because there’s a story out there that they’re all miserable, that they’ve got mental health issues, that they’re all suicidal. They’re not all suicidal. They’re living their lives. They actually love being queer. So to be able to amplify that message so that it can live right side by side with, “Yeah, and we’ve got to listen to young people too, but you also have to listen to them, the whole world.”

AA: Two things are really standing out to me as you’re talking. The first one is how you talked about when you were younger, just that feeling that you knew there was nothing wrong with you (thank goodness), but that there wasn’t a place for you in the world and that there was no future for you. And so again, what you’ve created is this opportunity to create the future that hasn’t existed for queer folks of the past but it’s like… Okay, it’s time. So now what do we do? We create the future that everyone deserved all along, but that now there’s space and we can and you’re doing that and that’s just…

CL: More importantly the young people themselves are doing it. Because what’s really touching is that, in the podcast for instance they wanted the first episode to be about queer joy. And what their guiding principle was, was they wanted to make sure that a young person out there who is listening to this podcast, a podcast made by and for LGBTQ+ young people, would inspire young people to be themselves. That was their goal.

AA: Yeah. It’s so powerful. And actually the other thing that came to my mind is the analogy that I just used a few minutes ago where I was like, ‘it’s like a little mouse going into the arena.’ And I thought, that’s how I felt, but obviously that’s an illusion. I wasn’t a mouse, and nobody, nobody is a mouse standing up to a giant. We’re all equals. It’s just the way that we’ve been made to feel, right? That we’ve absorbed enough messaging about where our place is in the hierarchy. And so my life experience, I have been really, really reteaching myself to enter a room knowing I’m nobody’s superior, but I’m nobody’s inferior either. We’re all equal.

And so, to see that this next generation, maybe they don’t… I mean, how amazing that for them to never have bought into that. If they can just walk into a room and they don’t have that feeling that so many have had that like, Oh, I’ve been made to feel so small by this system or by this religion or by this family or by this school environment, I now think of myself as small. No, they go in and they know like, Oh no, we’re just two human beings and we are equals and we’re going to negotiate this law or this, you know, policy or just this relationship as equals. That changes the world.

CL: This is to me the greatest harm that patriarchy has done. It insists on a hierarchy, and it actually dictates where you fall in that hierarchy. It not only insists on the hierarchy, but it insists on enforcing that hierarchy. And I think what’s so beautiful about these queer young people is that they have been experimenting with living in a big tent called L G B T Q I A plus, plus, plus. We make fun of it to a certain extent, you know, it’s sort of joked about in the culture, but the fact is what they’re doing is, in that tent, they are equal. They’re trying to equalize. Like there was a period when gay men had all the power. Right? There was a period when lesbians had all the power. Now it’s like, No, this generation is experimenting with being asexual is just as valid as any other of those alphabets. And I just think that that’s a beautiful thing.

And when you say they have the confidence… They have the confidence because they have each other. I did not have anybody. I didn’t have any people of my generation. I thought I was the first queer person in the world. I thought I was the only person in the world until I was about maybe 15. And then I was like, Oh, this is the thing. But to live in that kind of deprivation from your community, right? These young people did not have to go through that. And that is progress. And I will not have that taken away.

AA: Yeah, it’s amazing. Well, how can listeners find The Future Perfect Project? It’s online. I saw the website is fabulous. How can people get involved or help with it?

CL: So, it’s thefutureperfectproject.org. I think the best advice I can say is just immerse yourself in the delight of it, of what we’re offering. The animations, the album, the podcast, like educate yourself, listen, listen to what you hear, and then turn other people onto it. Because we’re a small organization. We’re a small but mighty organization with a big mission to really change the culture and include them. So that’s one way.

I think that if you’re a queer young person, between the ages of 13 and 22, and you want to get involved, a really good way to do it is to come through our Writer’s Room, which we have twice a month, and it’s a forum where we meet, we discuss, we create a container for people to be creative using words, and it’s just a way to be able to hear what other young people are creating, to be a part of a community. It’s especially helpful for people who don’t have access geographically to a community. They can go online and do that. That’s really easy access.

And, you know, reach out to us. If you don’t see something that you like, figure out how to get in touch with us, which is basically contact at thefutureperfectproject.org and just write to us and say, “I want to be connected.” And we’ll figure out how to connect you to the work that we do.

This is to me the greatest harm that patriarchy has done. It insists on a hierarchy, and it actually dictates where you fall in that hierarchy.

AA: Fantastic. I love that.

CL: And of course, it’s always nice when people donate to help us do the work that we do. Because I think that what I have seen is that when young people see themselves reflected in the culture, they can then go out and reflect themselves in the culture and actually work for the betterment of everybody.

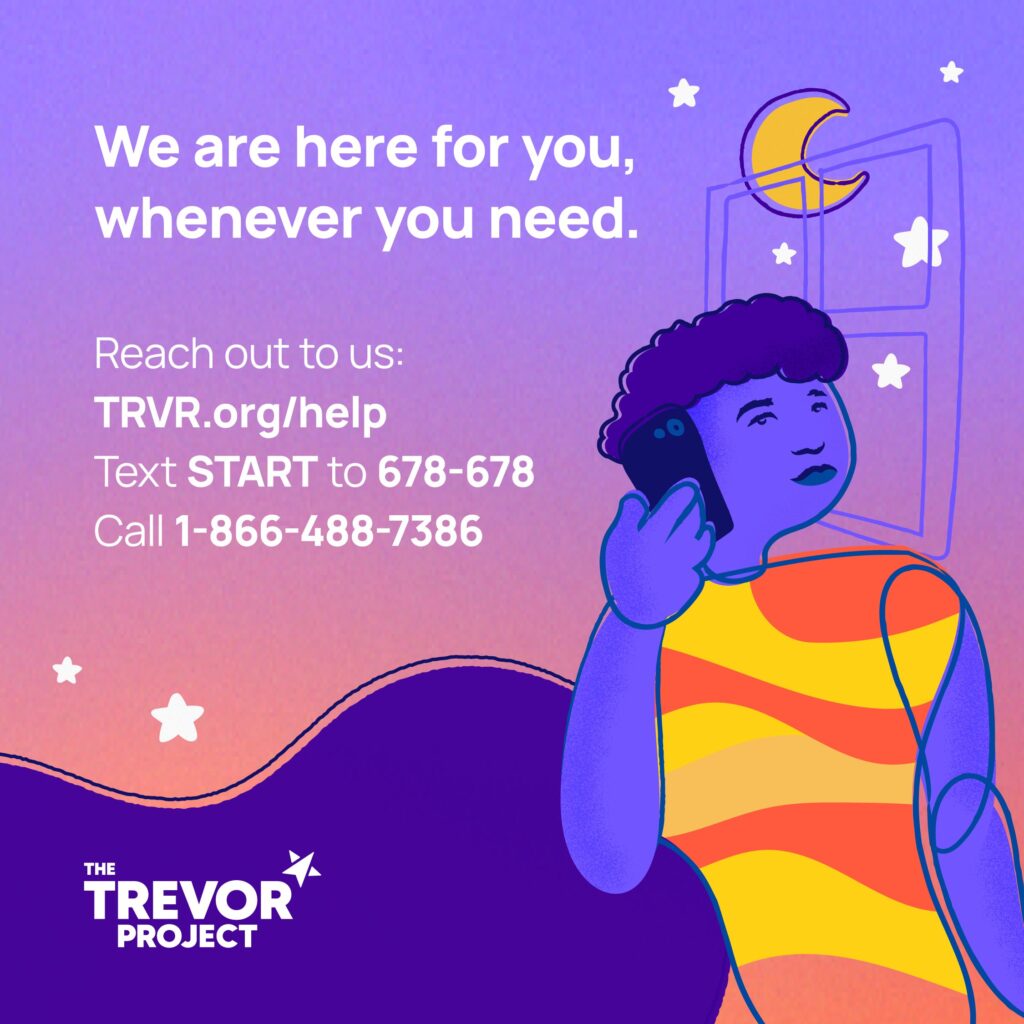

AA: I love that. And The Trevor Project also, I just want to throw in another plug for that too. That’s still going strong and I imagine it still needs volunteers and donations over there too, is that right?

CL: Oh, absolutely. I mean they have a lot of ways to participate. Like I said, there’s Trevor Space, there’s Trevor Text, there’s Trevor Chat, and then there’s really just picking up the phone.

And you don’t have to be in a crisis to call the Trevor Lifeline. You just really just need to be a human being who needs to reach out to another human being, and know that that’s available to you 24/7. Just know that it’s there.

AA: Yeah. What a beautiful, and such an important service.

Well, Celeste, as we wrap up, I just want to ask you if there are any kind of last lessons that you’ve learned or takeaways or things that you want to leave with listeners before we have to wrap up?

CL: You know, I can only speak from my own personal experience, but I think that something’s happening in the world. And young people know what it is, and they can see it. And I just want to encourage everybody out there to really take the time to sit and listen to young people.

Ask them the hard questions. Ask them if they’re okay, and let them know that you’re a safe place for them to bring their troubles to and their joys, because really it just takes one person in the life of a queer young person—and this must be true for everybody—it only takes one person to reduce the level of self-harm, even suicidal ideation, down to practically nothing. It just takes one person, one safe person in that young person’s life.

So I just want to encourage everybody to be that person and to understand that they have their own truth, their own gender that has never happened in the history of the world, their own sexuality that will never be expressed except through them in the whole history of the world, and their own faith that is looking for a community. So be that community for those people. That’s really all I can say.

And the risk, of course, is that they will change you. Like, you introduced me as James Celeste Lecesne, and the fact is, Celeste is my middle name. But because of those young people, meeting with them every day online during the pandemic, they made me understand something about myself that I didn’t know. And so Celeste, which was a source of shame to me as a child… I was so terrified as a child that people would find out my middle name was Celeste and mock me even more. So, as an adult, to be able to reclaim that part of myself, the feminine, that was hiding inside of me. They gave me that courage. They changed me. They made me see myself in a different way, after how many years?

So I think that’s the risk you take with young people, is you have to be willing actually to ask yourself the hard questions too, like, who am I? And why am I here?

AA: Hmm. That’s powerful. I love this episode for so many reasons, and one of the reasons that I’ve loved it so much is that I feel so much hope. I feel so much optimism. And sometimes when we talk about these really difficult topics, it’s true we have to get into why things are the way they are, and the history is really sad a lot of times and the state of things is really depressing and that’s really important to unpack, but sometimes I can get mired down in that and it’s been so inspiring to talk with you today, to be able to envision a future that is improving and that is full of thriving and joy for everybody. So thank you for the work you’ve done creating that world and thank you for the conversation today.

CL: Thank you, Amy. It’s really just been a joy to be with you.

AA: For me too. Thanks Celeste.

where they’re safe, where they’re seen, and where they’re celebrated,

everybody’s doing better.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!