“hope was the only thing that sustained me”

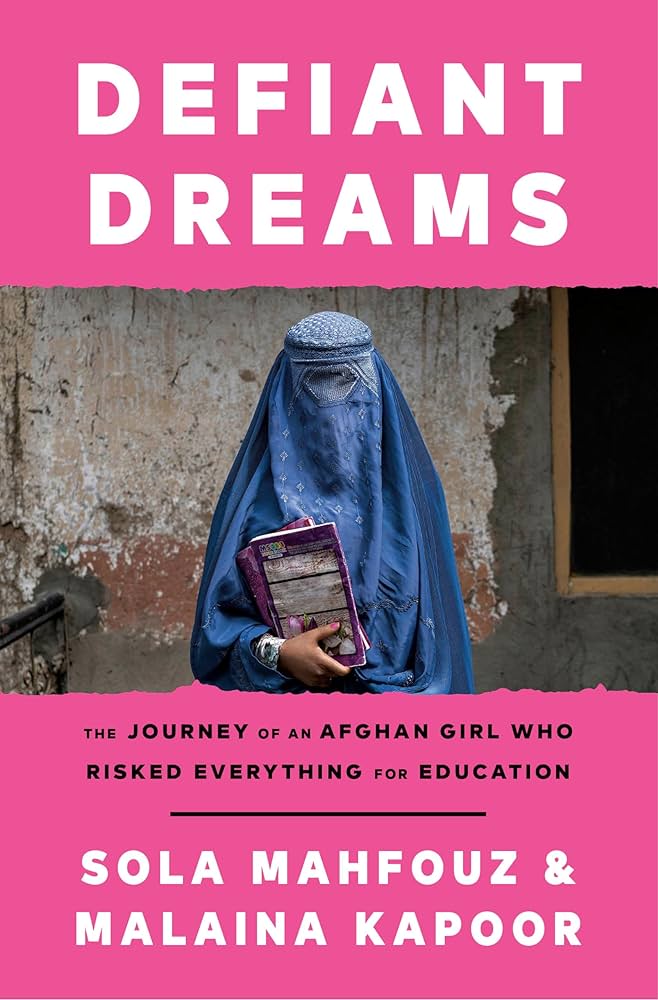

Amy is joined by Sola Mahfouz & Malaina Kapoor to discuss their book, Defiant Dreams: The Journey of an Afghan Girl Who Risked Everything for Education, and explore the ongoing struggle for women’s education in Afghanistan as well as Sola’s remarkable journey from Kandahar to quantum computing.

Our Guests

Sola Mahfouz & Malaina Kapoor

Sola Mahfouz was born in Afghanistan and immigrated to the United States in 2016 to attend college. She is currently a quantum computing researcher at Tufts University Quantum Information Group. In her free time, she is focusing on reading and studying different styles of fiction, as well as writing about the rugged homeland he’s left behind.

+++

Malaina Kapoor is a writer from Redwood City, California. She previously served as a fellow at PEN America, where she advocated for international hu man rights, press freedom,. and election integrity. Kapoor served on the management team of a refugee resettlement organization an was the producer of In Deep, a nationally syndicated public affairs radio broadcast program. She as received national awards for her poetry, personal essays, and short stories, and will graduate from Stanford University in 2025.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: During season three of this podcast, we aired an episode on the history of Afghanistan with Dr. Bahar Jalali. I learned so much during my research for that episode, so if you haven’t heard it yet, you may want to queue it up after this one. Dr. Jalali talked about long periods of thriving prosperity and advancement in Afghanistan. She talked about international meddling that destabilized her country over and over again. She talked about the tensions between conservative religion and progressive values and between diverse rural tribal cultures and urban centers. And above all, she talks about the dramatic back and forth of women’s civil rights, sometimes granted and sometimes violently taken away. Today I am so excited to zoom in on one woman’s story through the book Defiant Dreams: The Journey of an Afghan Girl Who Risked Everything for Education by Sola Mahfouz and Malaina Kapoor. I’m thrilled to welcome to the podcast the authors of this book. Welcome, Sola and Malaina!

Malaina Kapoor: Thank you for having us!

AA: I’m so excited to jump into the discussion. First, as I always do in the episodes, I’ll read your official biographies and then I’ll let you tell your personal stories after that. Sola Mahfouz was born in Afghanistan and immigrated to the United States in 2016 to attend college. She is currently a quantum computing researcher at Tufts University Quantum Information Group. In her free time, she is focusing on reading and studying different styles of fiction, as well as writing about the rugged homeland she’s left behind. She lives in Boston.

Malaina Kapoor is a writer from Redwood city, California. She previously served as a fellow at PEN America, where she advocated for international human rights, press freedom, and election integrity. Malaina served on the management team of a refugee resettlement organization and was the producer of In Deep, a nationally syndicated public affairs radio broadcast program. She’s received national awards for her poetry, personal essays, and short stories. Malaina will graduate from Stanford University in 2025. Congratulations to both of you on amazing work! Malaina, I’ll just throw out that my husband and I are both Stanford grads from graduate school, and two of our kids were born at Sequoia Hospital in Redwood City.

MK: Oh, wow, I was born there too!

AA: So cool! Okay, we’ll have to chat after. I’m so excited to have you both here. I’m wondering if you could take turns telling us a little bit more about your personal life, where you’re from, and then what brought you together to produce this book.

Sola Mahfouz: Yeah. I was born in Afghanistan in 1996, the first time the Taliban was in power. So there was no school for girls, but I was a kid then. But in 2001 the Taliban was ousted by the US and its allies and schools reopened and I started going to school. But, you know, once I went through such a dark time of civil war and then the Taliban time, the schools were not an intellectually thriving environment, but that too came to an abrupt end in 2006. When I was 11 years old, a group of men came and threatened my family if I continued going to school, and so that was the end of my formal education. And from that day on, the restrictions on my life continued to increase. I got to leave home only a couple times a year, and whenever I did I had to wear the suffocating burqa that covered me from head to toe.

Meanwhile, my brothers were going to school and they were thriving and I began to feel jealous of their life. They seemed to have this purpose and they were advancing every day. And my life, meanwhile, was like dancing to the rhythm of the outside world. The political situation was getting worse and worse, suicide bombing, exploding, and fighting. And so I asked and searched for the meaning of my life. I was 14 and I thought about my grandfather who was self-taught and said, “If you know English it’s like opening a window to the world.” And I felt the world outside me was dark and I needed that light to come in. In Pashto we have a saying that light equals education, that they’re synonymous. So I started learning English and then I went on to study math and physics using Khan Academy. In three years, I was able to go from not knowing how to add and subtract to studying college-level calculus and physics, and all because I wanted to understand the world. And so Defying Dreams is my story in Afghanistan and how I overcame all of the challenges to be here in the US as a quantum computer researcher.

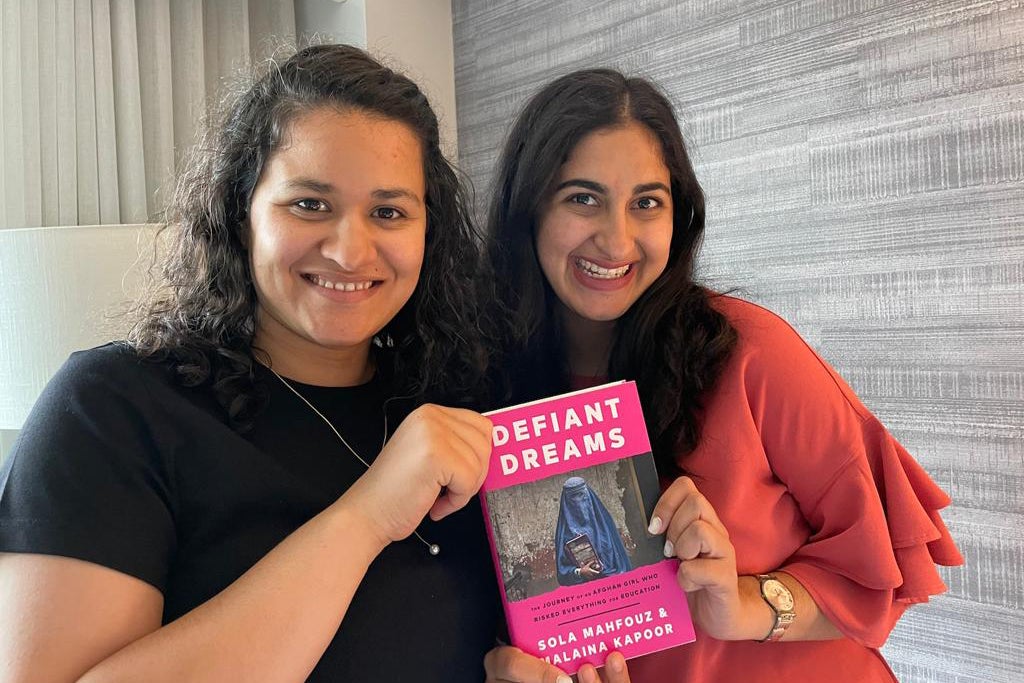

MK: My background is that I was first introduced to Sola in 2020 in the middle of the pandemic. At that time I had just graduated from high school and I was taking a gap year before starting at Stanford. And I knew very clearly that these issues around education and women’s rights were really important to me, and Sola and I really connected immediately on that. She knew that she was looking to tell her story, but she was looking for someone to do that with. So we initially met over Zoom, you know, we couldn’t meet in person, but Sola started telling me these incredible stories from her life and I started writing them. And over that COVID year, that became the basis for this book, Defiant Dreams. Eventually, Sola and I were able to meet in person and develop this close friendship that I think came out of the process of writing the book, because someone can’t tell you the stories from their life just in a vacuum, right? It has to be a give and take, and we really formed our relationship, I think, based on our long conversations, based on our very similar cultural backgrounds, and based on our shared values and goals and dreams for what came next.

And initially, this book was supposed to be Sola’s life story of how she was secretly educating herself in Afghanistan, the danger she faced in trying to escape, but how she made it to the United States. But during the process of us writing, the US withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021 and then the Taliban subsequently took over the country again. And I think that the book and our partnership feels much more urgent today because now there are millions of girls in Afghanistan who are living Sola’s story, who are forced to stay within the walls of their home and are unable to access education or even go out without a man accompanying them. And so that really has become the focus of what we’re trying to do.

AA: Yeah, this is really incredible. I got chills and tears in my eyes already, Sola, with you telling your story. One thing that really struck me is that when you said you learned on Khan Academy, like so many people across the world, I thought about the incredible democratization that has happened because of internet access. That people can have access to education even if they can’t go to a schoolroom. So that brings up a lot of questions, one of which is: how did you have internet access? Did your family have a computer? And maybe more broadly, can you tell us some more details about what that self-education process was like for you?

SM: Yeah. First of all, there were not a lot of learning materials. I started learning English and I would be watching for hours and hours on BBC and CNN and I would understand a word or two. And that felt like I was in the dark and there were just flashes of light once in a while. But I still kept doing it. And then, yes, at that time we had internet, but it was slow dial-up connection. It would sometimes take an hour just to connect. I would always compare myself to my grandfather. I was like, “If he could do it at that time, when he only had a radio or a dictionary, I can do it now.”

And then after two years of learning English, I wanted to study something more because I was watching news all the time and on TV there was war outside and I didn’t want to be surrounded by war all the time. My brother was going to Pakistan and I asked him to bring me anything that’s in English. So he brought me this TIME magazine and I found out about Khan Academy, and immediately I felt like this is what I needed. And I did have a laptop because my sister was living in England so she sent me one. I opened up Khan Academy and I saw the first advertisement for algebra, and I felt like this was too hard for me because I’d overheard conversation from my brothers and cousins when they talk about, like, “this one-line equation, it takes pages and pages of proofs and then at the end you just get one answer.” And I was so intrigued by how that could be, but I was like, “This is not for me. I just don’t know anything.” So, I was disappointed.

And then I asked my brother what comes after addition and subtraction, and he told me that it was fractions, and when I searched, I found fractions. And I also learned that I actually didn’t really know my addition and subtraction really well, so I went back to study that and I was just obsessed with it because it was like entering a different space of my mind. It was like building something in my head and it felt really freeing and empowering. And I think that even though it was really hard, that feeling of freedom that I’m able to do something by myself kept me going.

MK: I think too, something important for us, to your earlier question, to represent in the book was this fact that there is a plurality of experiences in Afghanistan. Sola was fortunate to come from a family that had access to the internet even if it was this incredibly slow dial-up connection that was something we experienced decades ago in the United States. But still, her family had enough money where she could have access to a laptop. I think the point remains that even someone with a few opportunities that not everyone in Afghanistan had, even given that, she still faced so many obstacles. The fact that even though she had that internet connection, when she would go on Khan Academy she would have to log on in the middle of the night because that was the only time that she wasn’t required to cook and clean as a girl in her household. She would have to download these videos one by one, incredibly slowly.

And then there were these mental blocks, too, that we’ve talked about a lot. This idea that in Afghanistan, most girls are raised to believe, or conditioned by the environment around them to believe that somehow girls are not built to gain an education. Sola has told stories about how she would study for hours at night and then she would get a headache, like we all do if we’re looking at a screen or trying to work on something. But she would see that initially as proof that girls are not meant to study. You know, “I’m getting sick because I’m a girl and I’m studying.” And there were so many of those kinds of things to overcome, but I think the fact that she continued to seek out that education really proved how essential it was to her at that time.

If he could do it at that time, when he only had a radio or a dictionary, I can do it now.

AA: Wow. That’s really powerful. I’m so glad you talked about the plurality of experiences because even in my very limited experience, I’ve been working with Afghan families of refugee backgrounds where I live. I now know four families and all of them are roughly the same age but they’re from various places in Afghanistan and extremely different circumstances. A couple of the women don’t read in their native language, they speak Pashto and they don’t read and can’t sign their names. But then other women, again, of the same generation, were teachers in Afghanistan. So I know not to reduce people to a single story and to reduce people to what you see in the news, but even for me, I was like, “Oh!” and it shouldn’t have been surprising, but it was. I’m just so glad to have you highlighting the different experiences that people have and how, I mean, I know there are even microcultures within families everywhere in the world, about how you approach education and gendered expectations and stuff. So interesting. Would you be able to tell us a little bit about your parents’ experience? What were your mother’s opportunities like in her life?

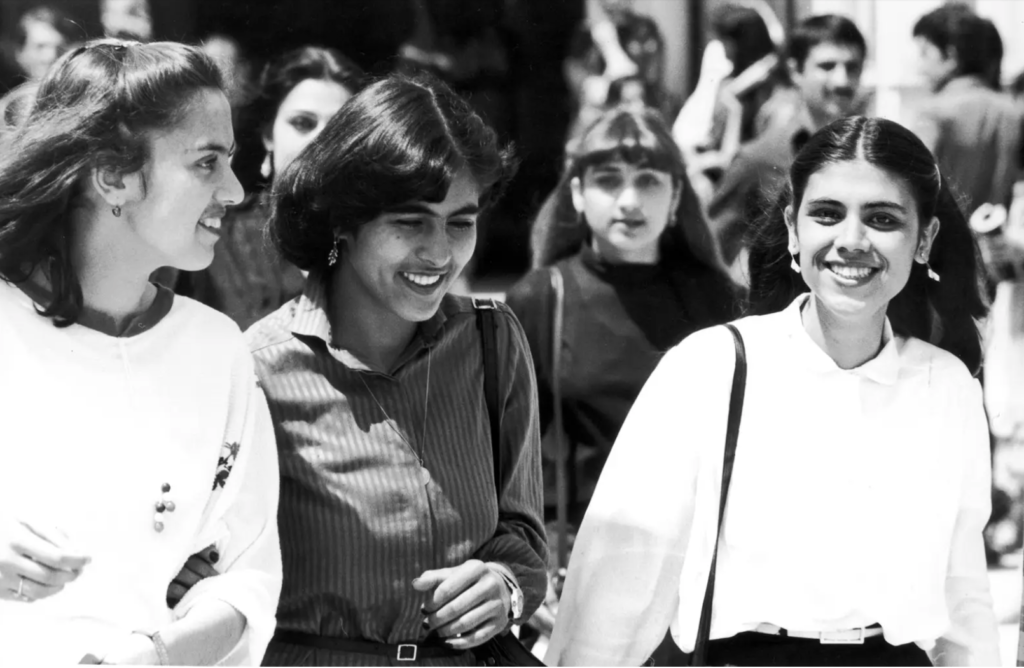

SM: Yeah, so my mom was born at a time when Afghanistan was making a new identity for itself. It was modernizing, schools were opening, universities were opening, and there were international exchange programs at Kabul universities. And when she tells me stories it feels like it’s somewhere from a fairytale. When she was telling me, I was not able to put her stories into the Afghanistan that I knew. She went to school and her whole life was all about like, “Okay, what’s next? What university, what should I study?” And all of that. And it’s also really important that the Afghan identity, especially women’s identity, is shrouded by the burqa, but it wasn’t like that all the time. She tells me stories of how, in addition to education, there was this obsession with fashion. She was from Kandahar and went to Kabul University, and she told me this one story of her friend, who one day wanted to do a new hairstyle to have volume, and it was Kabul winter, and she turned on a fan and then she got sick because it was cold, and she missed lectures for a few days. And that was what was happening. But of course, there were also, as you mentioned in the beginning, these forces that wanted to go back to the old ways. And also because it was the time of the Cold War and against the Soviets, there was international funding for these groups. There was always this back-and-forth and there were threats, but for some time Afghanistan was on its way to become a place where women and men were equal and a new nation state was being built.

MK: Yeah, I would add that Defiant Dreams is obviously Sola’s story, but we made a conscious choice to actually start with the story of Sola’s mother, about her experiences as a student at Kabul University and then as a professor, taking the bus by herself and going to concerts with her friends. Because it really shines a light on how different Afghanistan was and maybe could have been, but also I think it brought out a very central theme in the book, which is this idea of mothers and daughters and the idea that in Afghanistan there are generations of mothers who have experienced more freedoms than their daughters ever will now. You mentioned those women who were teachers and worked in big cities, and now their daughters can’t even go to school past the sixth grade.

AA: Well, let’s talk about that more. Maybe we’ll save that for the end of the episode, talking about the situation right now in Afghanistan. But first let’s continue on your life path, Sola. You can tell us from this period where you were educating yourself at home, how did you get from there to becoming a quantum information researcher? And knowing that that’s the end of the story, when you started talking about needing to learn fractions, going on that journey to where you are is just incredible and so inspiring, so take us through that journey.

SM: Thank you. For me, there were a lot of questions in my head. Why does the world work the way it does? And also the patriarchy, how it fails to convince me with logic that I can’t do things just because I’m a woman. There’s the meaning of life and then that led into more philosophical questions of the existence of not just my life, but of the world, why the world exists and all of that. So when I started learning fractions, I would start looking more at philosophy and also cosmology. I knew that for me to be able to study more of that at a higher level, I had to study more math. So that was really my motivation to do more. And also, as I said, it was the feeling of empowerment. I would study for every eight hours or something, every hour that I got I would study. And for English, I would translate vocabulary and then record in my own voice so that if I was washing dishes or anything, like, every minute of my life I wondered, “how can I learn?”

And in 2012, that’s when I started learning math and science. In 2015 I felt like I wanted to go out, and at my age there was also the societal pressure to get married. I also wanted to not get married, just to study, and that was not an easy path. I saw my brother going abroad to study, but I didn’t have a high school diploma or anything like that. I first took the English exam and something to prove my high school equivalency, so I went to a local education ministry but they denied me an exam where I could prove myself. So, that was an end. And then I looked up and said, “If there’s any other international exam that I can take…” and I found out about the GED. And again, I didn’t have the books to prepare. So I asked my sister who lived in England to send me something, and she did send me the preparation books. It took a few months, but then it arrived, so I spent a few months on that. And then finally to take the exam, when I searched, there was no exam in Afghanistan and there was also no exam in Pakistan. But I really didn’t want to give up hope because hope was the only thing that sustained me, and I didn’t want to lose that.

And so I thought, “Okay, if I can’t do this, let me just focus on the English exam, let’s take that and see what happens.” So I started preparing for that. And while I knew that my reading skills and my listening skills were good, I did not know about my spoken English. So I looked online and I found this website, conversationexchange.com. It’s a website where you put your native language and then you put out another language you want to learn. So I got connected to this American girl in the US and we started talking. And then she was like, “How do you know all of those things?” And, “I think you’re at the level that you should come to the US for university. And then she told me about the SAT, that in order for you to come to the US and apply to the universities in the US, you should take the SAT. And that’s when I found out about it and immediately I started looking at it. And again, it was not available in Afghanistan, it was only available in Pakistan. I made the decision that I was going to take it, and it was a very hard and arduous journey. But again, I kept focusing on what would come at the other end of it.

MK: Yeah, I remember when I heard this story for the first time, of how Sola really had to fight to get out once she already had her education, that she just needed a pathway out, I was amazed. And when we were writing these chapters, I remember I would call her all the time and say, “I just can’t understand, how did you go from at 16 not being able to add and subtract to at 19 doing college level calculus and physics and reading philosophy?” I think it’s something that’s hard to understand from our position in the United States. And I would call her over and over and she would try to explain. I think what I finally came to understand is that in many respects, learning is such a natural part of growing up here, of course, but for girls in Afghanistan, especially girls growing up in Kandahar, where Sola grew up, your life becomes defined first by whose daughter you are and then by whose wife you are. And in Kandahar, a sign of your daughter’s beauty or value was how young you could get her married. It was common for girls to be married at 10 years old. 14, 16, 18 is considered late. That was the life that she saw for herself.

And in light of that, I think the motivation to keep learning and keep going became something that maybe you could never even find in a place like the United States. And then there were the incredible obstacles. As she mentioned, she tried to take so many exams, she tried to have her sister send her prep books for an exam that didn’t even exist. And Kandahar didn’t even have a mail system at that time, so the books had to come from one person to the next, and they took months to arrive. And then there was that SAT journey where Sola crossed into Pakistan. The Afghan-Pakistan border is one of the most dangerous borders in the world. It’s a border where people are regularly beaten with electric cables, where men and women have to cross separately, where you have to take multiple vehicles just to get across. And that was the journey she had to take just to sit in an exam room and hope she could get a score high enough to apply to universities.

AA: That’s unbelievable. That’s blowing my mind. I’m thinking also with these conversations, I can imagine it as you’re writing the chapters and going, “Wait, how is that even humanly possible?” And Sola going, “I don’t know. I’m just really, really smart and really, really dedicated,” haha! I actually don’t even know how it’s humanly possible to make that much progress in that short of a time, even if you had every advantage, but to think of all the disadvantages. It’s really incredible. Okay, I want to know more about the journey. So then you took the SAT in Pakistan, is that right? And then how did you get to the US? What kind of visa and how did you get it? Where did you go to school? How did you end up at Tufts? Tell us everything.

SM: Yeah, so I took the SAT and I scored high enough to apply to universities, and that’s what I did. And then the next step was to apply for a student visa to come to the US as a student. And so I applied for an appointment and with my mother I flew to Kabul. And this was the first time she was also seeing Kabul after leaving it and the civil war. So I went to the US Embassy in Kabul, and in one minute my visa was denied. The officer just told me, “We can’t give you a visa.” And when I asked for an explanation, he said, “Well, I don’t think you’re going there to study. You’re just going there to immigrate.” And this was the first time I also saw how the world sees Afghans, as these desperate people who just want to immigrate and just go there to, I don’t know, work or whatever. And I just felt like I was falling into an abyss, because whatever was in my hands I did, but this was not in my hands. I was crying and asking, “Why, why are you denying my visa?” I knew that I couldn’t just go back and resume a normal life because I knew I could do this. I passed the exam and I got accepted to university. How could I just go back? That was the end of the student visa.

your life becomes defined first by whose daughter you are and then by whose wife you are

But my friend Emily, she was also very furious because over 20 years the US had been saying “we are helping Afghan women,” all those things. And it’s also this image of “Here I am. I studied, I did everything,” and in the context of what was said, I should be able to come and study but yet I was denied. Later, I was talking to some professors here in the US and they all came together and I was able to get the humanitarian parole visa, which is kind of a one-way visa. So that’s how, one month after my visa was denied, I came. And I did not know when I would be able to go back. And of course it changed how I was initially coming, and also my perception of the world. Everything that I felt like I knew about the world just broke down and I had to rethink the world and how it works. So I came to the US and I started university at Arizona State University and I was studying physics. And then I came to Tufts University because of my interest in understanding the world and also philosophical questions about the world and quantum information. Quantum computing really is a field that’s at the intersection of physics, philosophy, and trying to understand the world from entering the atom and then seeing how the whole world emerges out of it. And it’s been four years that I’ve been with Tufts.

MK: I was going to add that I think that story, you know, there’s that period where Sola was rejected. The visa officer rejected her, and then fortunately she was in touch with people here who were able to rally and help her to get that humanitarian parole visa. But that state of limbo, we write a lot in the book about just how devastating that was. And also because, as Sola touched on, she took a massive risk as well in educating herself, not just because people might’ve found out or because there was a danger inherent in going to school, but also because the knowledge she was exposing herself to and the world she was exposing herself to outside of Kandahar, Afghanistan meant that it was almost impossible then for her to ever exist in the society that she had grown up in. And in the book we write a lot about tensions around this that involved Sola’s mother. Because on one hand, she was a woman who deeply valued education, who saw it transform her life, and wanted that for her daughters. But she also realized that if she encouraged her daughters to seek that out in a place where that was not rewarded and where it was actually something that might prevent them from living a safe and secure life, there was also danger in that. And so her mother wrestled with a lot of that, on one hand, not wanting her to do some things, but on other hand, flying with her to Kabul to try and find that way out. And now, and I know we’re going to talk about the future later too, but I think we write in the book about how Sola then had to grapple with that when staying in touch with family members who are now in Afghanistan, young family members, where you want to gift them what English has to offer, you want to send them books and articles and poetry. But at the same time, you realize that if they start to vocalize the thoughts and ideas that are in those texts or start to dream of a life outside of the country, then that can be a real danger.

AA: Yeah, a physical danger, right? But I can only imagine how excruciating that would be to feel that tension that once you open it up and introduce those ideas, if they don’t have access to the path to be able to pursue it it’s almost like setting you up for a life of frustration and sorrow at something that you can’t have. That would be so hard. Okay, I have so many questions, and everyone just needs to buy the book and read it and get all these questions answered. But one thing I wanted to ask, too, is that you went to Arizona and then to Massachusetts, two extremely different places from each other and both so different from Afghanistan, did you go by yourself? Did you arrive in Arizona all by yourself or did you have anyone with you?

SM: Initially I arrived in Chicago and that’s where Emily was, my friend, and she picked me up. And after a few months of me orienting myself in this new country, she actually flew with me to Arizona State University and stayed for a few days. And, yeah, I was able to take a tour.

AA: That’s incredible! And even that, oh, that’s hard for anybody. Again, as a college freshman it is so hard to go somewhere new. This is just amazing. And now you’re at Tufts doing quantum physics and philosophy and that’s just incredible. I want to maybe broaden the conversation a little bit and talk about how your experiences shed light on the broader issues of women’s rights and education access. I have specific questions and thoughts, but I’d love you to answer that question.

SM: I think the first thing is that a lot of the time there’s not that strong feeling of how much we value education. And I’ve seen it with myself and now with so many family members, I say that if education is given, it’s taken for granted. When it’s taken away, it becomes a secret thing, and then getting it becomes the ultimate defiance. And I think that knowing that, and also when we feel that, then that will make us more aware of what Afghan women are going through. And a lot of the time it’s the thing like, “Oh, it’s the culture,” or things like that. But that’s not true. Look, my mother, back in the 1960s, that was so different. And also what’s happening right now is not an Afghan culture. And also it’s not like the women just silently accept this thing. Their blood is boiling with anger, and if you become aware of the pain there, then all of us would like to look for a solution. And also, the amount of energy the Taliban puts out every day in suppressing women, if you even put a fraction of it in helping back, we would see a very, very different result.

MK: And I also think that a real goal with the book was to humanize the situation. Because it’s easy to read in a newspaper article that millions of girls are denied education, but it’s hard to actually understand what that means. And so our hope with this book was that when readers understand the history of Afghanistan through Sola’s parents and grandparents, and when they feel like they’re on the journey with her to try and find that education and try and get out and understand the incredible obstacles she had to overcome, and then multiply that by two million, because that’s how many other girls are stuck in similar situations today and there have been even more in the past, hopefully that allows people to gain a deeper understanding of the issue. I think it was certainly true for me. Growing up in the United States, I think I had an understanding that these were serious issues in other parts of the world, but by first hearing Sola’s story and then getting to know her really personally, I think it changed my conception of just how dramatic these human rights violations are. And then what they mean on an individual level and how much progress can come if we lift those restrictions even on one girl.

AA: Yeah, for sure. That’s what I was thinking too. I just got this sense of the potential energy in each individual human being, and your potential, Sola, that you were able to just blast out once you were given an avenue for it. It was just this incredible raw intellectual potential, and that now it has an avenue and you can reach your full human potential. And just the incredible tragedy for each individual who isn’t allowed to do that, and then the loss that the entire world has experienced by not allowing all of these humans to flourish and make their contributions. We could make such progress if we just, like you said, remove the restrictions so that each individual, and then multiplied out, can reach their potential. So, what changes are necessary to address the education disparities for women and girls? Because this is obviously a huge problem in Afghanistan, but also in other countries as well.

MK: Yeah, I think that what Sola’s story really highlights is first the fact that there are really profound institutional barriers that prevent women, specifically in Afghanistan but across the world, from accessing education. So that looks like the visa officer who can reject an application in one minute even though that woman has been studying for years, but that also means a lack of access to physical schools or teachers. This is a question that Sola and I have gotten often as we’ve traveled and talked about the book and her story, and it’s a very difficult one to answer. But I think what her story demonstrates most clearly is that power of technology, and we think it’s important to invest in solutions for girls who can’t access the internet, and in the specific case of Afghanistan, build solutions with these Afghan women in mind. For example, right now there are some initiatives out of the State Department to bring online learning to Afghan girls, but those are insufficient because of their partnerships with private companies. And Sola knows from experience that you can’t even download videos from those companies in Afghanistan because the internet simply isn’t strong enough, or maybe there’s not language support, or maybe these programs are job training programs, but how will that work if there’s no infrastructure in Afghanistan for women to get a job? So, my perspective is that it’s a combination of real private sector investment in building these technological solutions, and then there is a responsibility for all of us to continue to keep the stories of these women alive in Afghanistan in the headlines so that there’s then pressure on governments and these bigger institutions to help forge pathways out for these girls.

SM: Yeah, and not just pathways out but even when they’re there. And Malaina said there’s a lot of talk like, “Oh, let’s just turn away from the problem.” But if we really build something real and it’s not just like, “Oh, let’s help those poor women,” it shouldn’t be like that. Afghan women hold placards demanding their right to education, in Mazar-i-Sharif, Balkh province, on June 26, 2023 It shouldn’t be something like that, and a lot of the programs are like that. So I think one of the reasons I was able to use Khan Academy and loved it so much was because it is not a charity. It was something where immediately you went there and you felt this feeling of empowerment. And it needs to be something like that.

AA: Yeah, that makes sense. What can individuals do, people who are listening to this or watching this right now, how can we help support global efforts to improve education for women?

MK: I think the most important thing for individuals is, as I said, to continue to tell these stories. Because ultimately what we’ve seen in Afghanistan is actually that initially, there was a lot of conversation when the Taliban took over of maybe Taliban 2.0, maybe they’re different, maybe they want international recognition. And that was the story for as long as Afghanistan was in the headlines. And as soon as it faded away, that’s when the Taliban began this systematic program to strip away the core freedoms of women. That’s when they banned school for girls, that’s when they prevented women from working. And that’s continued over the last several years, where basically there are new edicts every week or every other week that continue to strip away freedoms from women. So, speaking from my own experience growing up in the United States, I think there is great power in movements that seek to bring these stories to the forefront. I remember when I was young learning about issues of girls’ education through stories of women like Malala Yousafzai, and then that grew into a massive movement among students but also among so many people in the Western world. I’m on a college campus right now, and of course college campuses were so integral to the fights against injustices like apartheid, and now there are people at the UN who are calling what’s happening in Afghanistan “gender apartheid,” right? This is something that exists at that level, and I think that continuing to talk about it and to feel angry about what’s happening and to understand the stories of individual women and girls, that’s the most important thing that we all can do.

AA: Do you think that partly, I’m just thinking about this, I struggle sometimes because I do feel so much anger and grief about what’s happening and I sometimes don’t know what to do, where to put it, what to do with it in a positive way. I don’t struggle to feel empathy, I feel lots of empathy and I’m educated about the issues, but then sometimes I’m like, I mean, writing to President Biden or writing to a senator or something, and then elevating women’s voices on the platforms that I do have are things that I’ve thought of to do. Sometimes donating to charities, but sometimes it just feels like a struggle. But I like what you’re saying, that if everybody puts that public pressure on then maybe it is something that our elected officials realize, like, “Okay, our constituents do feel strongly about this,” so that they make it a priority and it doesn’t just fall off of their agendas once The New York Times isn’t talking about it anymore, then they can forget. Is that what I’m hearing you say?

Afghan women hold placards demanding their right to education, in Mazar-i-Sharif, Balkh province, on June 26, 2023

MK: Yeah, I think that’s true. And I also really identify with that, sometimes you just feel overwhelmed with grief or anger, but like you said, it’s hard to place what to actually do with that. At least for me, I feel like that can often come from these sweeping reports that will say, you know, “millions of girls denied education,” or these kind of faceless pronouncements of how bad things are in the country. I think that what makes room for more hope, or hopefully gives people a place to put that energy, is when we start to hear more individual stories. And when, instead of in the letters referencing statistics, which of course are powerful in their own way, we also have access to stories of many, many more women like Sola. And we hear from women and their reactions to the recent Taliban announcement that stoning will now be a punishment against women, so that there’s some way for us to identify with the people who are going through this. And then also hopefully when communicating these stories to elected officials or to others, there’s again that deeply emotional individual connection.

SM: Yeah. And also, as Malaina said, when you talk to people, like I’m in touch, there’s times that they give me more hope because there’s so much there. They want to learn. Let’s say I would tell them, “Oh, I’m going to talk to you for an hour in English,” they’re so happy and for the whole week they look forward to this hour. And I was like that too once, you know, when I was there I would ask my cousin to practice English with me. And so I think that those small things might not change life on a bigger scale but they add so much meaning to life. And also, I think it’s not just that you’re helping the girls there, but they’re helping you back because there’s so much wisdom in them. And like in Afghanistan, first of all, it’s a country that has been an ancient civilization and there’s so much, even a 15 year-old had so much depth in what they say. It’s not just a one-way thing that you teach. They will teach you about life and as you teach them English. I think that just thinking in that way, well also, they’re not this all suppressed and oppressed, you know, there’s so much in there that they can offer to an individual and also the world.

AA: That’s great. I’m glad that you brought that up because that is something that people can do wherever we live, is to look at doing local volunteering. Like I said, I worked with these Afghan families and that’s just, as you say, enriched my life and my family’s life so much. Also having relationships and laughing with kids and being reminded that kids everywhere are the same. They’re funny and they’re silly, and yes, I’ve learned so much about slowing down and enjoying people’s company. Because Americans are so rush, rush, rush, rush, and having a long meal at first stressed me out and then I thought, “Oh, this is so much better! We need to adopt this way into our family.” Anyway, I’m wondering, as you were writing the book as you first conceived of it and then were writing and publishing, what were your goals specifically in writing this book? And what has your experience been as you’re talking to people who’ve read it and you’re you know doing book promotion? What is the impact that it’s having?

MK: I think that the main goal, as we talked about, was this idea of shining light on the situation facing women in Afghanistan through the very personal experiences that Sola has been through. I think a second goal for both of us was, how can we paint a picture of Afghanistan that hasn’t been painted before? Because I think, especially in the United States, we have this idea of Afghanistan, maybe in a Cold War context, definitely post 9/11. But what we lack is this very detailed picture of life there that’s colored by the individual experiences of people who live there. So that meant, yes, writing about Sola’s journey to take the SAT and logging onto Khan Academy for the first time. But it also means that one of the earliest stories in the book is about how when she was growing up, Sola’s father loved to dance, and how that was so different from the cultural expectations for men at the time.

We have chapters at the end of the book that talk about how even when bombs were exploding, how Afghans find humor in those moments and what is the very unique way that people laugh in Afghanistan. That’s certainly something that we encountered, Sola and I, when we were in this process of writing. Sola would tell a joke and I would be like, “That’s not funny but it is!” You know, something that is symbolic of the culture that she comes from, and that’s something we wanted to paint. We wanted to show that Sola is this driven girl hungering for an education, but also that sometimes she would just turn on Bollywood songs in the kitchen when she was cleaning. Or the fact that she loved to bike but she could only ride her bike within the walls of her compound in Afghanistan, so when she landed in the United States, one of the first things she did was go for a bike ride where she couldn’t see where she started and she didn’t know where she would end. Those are really beautiful moments and I think they’re moments that we could all relate to no matter where we come from. And it was important to us to share that side of Afghanistan, too.

And in terms of the reception that we’ve had as we’ve traveled and talked about this book and Sola’s story, I think it’s been incredibly moving to see. Because in many respects, even though we’re co-authors, so there were the two of us, writing a book can be a very solitary experience. And you know what you want to convey to the world but you don’t ultimately know how they’re going to interpret it. But I think what we’ve seen is that the book has really touched people who have lived through similar experiences in Afghanistan, in other countries in the Middle East, and who deeply identify with the story in that way. But it’s also touched people who maybe haven’t thought about Afghanistan in years or even since the time of 9/11, who weren’t even aware of what was happening to women. You know, soccer coaches who have bought the book for their entire graduating class of girls, people who have reached out talking about how they never followed global affairs or the news but this really struck a chord in them. And that’s been so rewarding and so important because it’s so important to spread these kinds of stories that very naturally touch people. There’s a platform to get them out to the world.

AA: Sola, did you have anything that you wanted to add to that in terms of how it felt to you to put your life story in a book and have lots and lots of people read it?

SM: Yeah, for me the important thing really was for me to, again, Afghanistan is seen mostly through a journalistic view and I saw so much complexity in one moment. We would be learning a dance for a cousin’s wedding and then in the second moment a bomb exploding and my aunt coming to the room and opening the windows so that it wouldn’t break because of the pressure. And we would still feel like it was something normal. We still continued like “Yeah, okay, the window is open and we’re safe.” We continued our dancing. And so I really want this dance between life and death always intertwined in Afghanistan and how we still want to make the best out of it. And it’s not that we don’t understand it, we understand so well, and we are still doing that. So I think that it’s not always in the news, it’s just that smoke rises and that’s all you need to know about Afghanistan. There’s so much more. That’s one of the reasons I was so passionate to tell my story.

And another thing I really think is that sometimes I really wanted to understand why women, women all over the world, why there are restrictions. You come to the US, you’re in Afghanistan, and I try to understand, is there something wrong with women? What is it? And so then I finally come to understand this bigger thing of patriarchy and how that has been imprisoning women in different ways. And seeing this thread of women’s oppression being connected to patriarchy, whether it’s in Afghanistan or in other places in the world. In some places less extreme, in Afghanistan it’s the most extreme version of it. And I think that trying to look at this world in that context, I think it helps. If we help Afghan women now, it’s like we are helping ourselves as well because we are all ensnared by this one thing.

AA: Yes, yes. Thank you so much for sharing that. That’s something that I feel really strongly, and I’m sure you know the quote from Fannie Lou Hamer, who was a civil rights activist, that nobody’s free until everybody’s free. And that’s something that really resonates with me. I’m dealing with patriarchy in my own faith context, in my own community, and the ways that it’s impacted me. But I’ve felt this incredible sense of sisterhood with women all over the world as I’ve done this podcast, and including today hearing you. And I can’t think of a more inspiring story about breaking down patriarchy, right? Breaking down the unjust barriers that hold women back and then creating something brave and new and beautiful. And just the defiant act of fulfilling your human potential. I’ve been so, so inspired by your story. I’m so grateful. I can’t recommend the book highly enough. Again, it’s called Defiant Dreams: The Journey of an Afghan Girl Who Risked Everything for Education by Sola Mahfouz and Malaina Kapoor. So, Sola and Malaina, thank you again for being here. It was an honor to have you.

MK: Thank you so much.

how much progress can come if we lift those restrictions

even on one girl.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!