“You are alone

and the advertising is telling you your laundry isn’t good enough.”

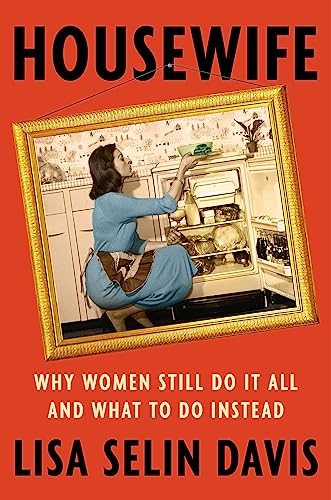

Amy is joined by author Lisa Selin Davis to discuss her book, Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All and What to Do Instead, detailing the surprisingly recent invention of the ‘traditional’ housewife, plus laundry, lobotomies, and why modern day tradwives might have more equitable lives than we imagine.

Our Guest

Lisa Selin Davis

Lisa Selin Davis is a critically acclaimed essayist and journalist whose work has appeared in major publications including the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Time, The Free Press, and many others. She is the author of Tomboy as well as two novels and she lives in New York City with her family. Her most recent book is Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All and What to Do Instead.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Growing up in the 1980s and 90s, I loved to watch reruns of TV shows that my parents had been raised on, especially I Dream of Jeannie and Bewitched. The main characters of both shows are beautiful and charming, and the plot lines were always fun and funny. But one thing I never noticed was that in both blockbuster shows from the mid 1960s, the main characters were women who had almost limitless power, and they chose to use that power in the service of the men they love. In I Dream of Jeannie, Jeannie is literally owned by a handsome young general named Tony, while in Bewitched, Samantha Stevens confines her enormous powers to a life of domesticity within the walls of her home. Or at least that’s what she’s supposed to do, which is the tension that provides the show’s hilarity. But I only thought back on the cultural messaging of those shows because they came up in a new book called Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All and What to Do Instead, by Lisa Selin Davis. This book connected all kinds of dots for me, and I am so excited to discuss it today with the author, Lisa Selin Davis. Welcome, Lisa!

Lisa Selin Davis: Thank you so much for having me.

AA: I’m really excited for this conversation. This book is brand new, it just came out, and I loved it. I highly recommend it to listeners to buy and read. Thanks for being here today to talk about it with us. I’ll introduce you professionally first, and then have you tell your own story afterwards. Lisa Selin Davis is a critically acclaimed essayist and journalist whose work has appeared in major publications, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Time, The Free Press, and many others. She is the author of Tomboy, as well as two novels, and she lives in New York City with her family. That’s just the briefest of intros, Lisa, and I’d love you to start us off with a little bit more about you. Where you’re from, how you were raised, and what kind of passions or interests brought you to do the work that you do today.

LSD: Yeah! I live in New York City and I’ve been a writer for the last twenty-something years. Before that, I worked in the film industry. I always wanted to be a writer, but I did not understand how to make the leap. I briefly went to urban planning school and then environmental psychology school, whatever that is. And then my brother said, “I don’t understand why you’re doing plan B.” So I decided to try plan A, which was writing. I initially started out wanting to write about urban planning in architecture, and was very interested in the relationship between the built environment and community. And this book is partly about that, because a lot of what happens to the American family happens during the growth of suburbia. And then I had children, so, as one does, I started writing more about parenting. And I had always been a feminist and was always interested in women’s issues, and I kept trying to bring all these disparate interests together while also cobbling together a living by writing about anything. So that’s how this book happened. And the book before came out of a similar confluence of interests and personal experiences. That book was called Tomboy and was inspired by having a very masculine daughter. And so this book, Housewife, felt in some ways like the next iteration of investigating these ideas, these words that seem outdated and seem like we’ve moved beyond them, but actually are exerting a lot of power that runs beneath our society.

AA: That’s really great. And I have to say too, just from my position and my lived experience and training, you and I are coming at this issue from opposite worlds. I was raised Mormon, and so I was very much trained to be a housewife, to only take care of children, never to work outside the home. And I’ve said on past episodes that it was like I lived under a bubble, like a force field, where the second wave of feminism never reached my family. And so it was really interesting seeing if there were a Venn diagram for your lived experience and your perspective and mine. We have a lot of differences but so much overlap, which is really, really interesting, where we come together, and see some of the problems that are afflicting women and everyone in society even though we have such different life experiences leading up to this point. It’s still affecting all of us in really negative ways. So, I’m so excited to have this conversation with you, and I so appreciate having someone with such a different perspective. Also you being from New York, and I’ve always lived in the West in the United States, which, you know, there’s a little bit of difference. Anyway, I’d love to jump into the book and ask you as many questions as we can fit in, because like I said, I absolutely loved the book.

LSD: I wanted to say, before we do that, I was just thinking that one thing we also have in common is that we were probably told there was one way that we were supposed to conduct ourselves as young women. And of course, mine was to not rely on men. My mom was a single mom and I hardly even knew married couples, which I am not romanticizing in any way. So I do think that what happened to me later was that I became much more interested in other ways of conducting lives and families, and very open to the idea that there are a lot of good ways to do it. And I think when you grow up in hardcore feminism, you look down on the kind of culture you were growing up in, and I see no reason to do that now. But also, I lived in Arizona for a while and I met a lot of Mormons and they were all very nice.

AA: Haha.

LSD: I once had a Mormon student write an essay about being an old maid at 18, and I think that always stuck in my head, too. I think that was on some level behind writing this book, too, of “look at all the different pressures women feel no matter where they come from.” I found that utterly fascinating because I’m in a world where people think it’s very odd if you get married before 30.

AA: Mm-hm. And like I said, we were in the Bay Area for 15 years, and people always thought I was my kid’s nanny because we did the whole Mormon thing. We got married very young, had four kids very young, but I was definitely the anomaly out there and people thought I was crazy. But anyway, I’m really glad you said that before we start. And I have to say, too, I so appreciated your approach throughout the book in having a lot of nuance and really clear-eyed curiosity about there being pros and cons to lots of different choices. And kind of what you said about how we have a tendency to look down on what other people do and go along with the training that we were raised in and think, “Oh, but there’s only one real way.” And I loved the way you brought up women’s real experiences and talked about it like, “Listen, we’re all doing our best, first of all, with the information we have, and here are some of the benefits and some of the risks of all of these different decisions that we can make.” So I really appreciated that. Okay, let’s start with a history, since everyone knows I love a historical timeline. You lay out the history of the concept of the housewife, starting with its definition, and then you start way, way back in history. Do you want to walk us through the history?

LSD: Well, I guess I started back before recorded history, only because at some point in the last couple of years I saw that there was an article that had been published about female hunter skeletons, 9,000 year-old skeletons that all the archaeologists had assumed were master hunter skeletons because they were buried with all of these weapons. And most archaeologists assume when they see that, that that means that that person was a very skilled hunter. Thanks to advances in DNA testing, they can test for the presence or absence of a Y chromosome, and there was no Y chromosome and it turned out to be the skeleton of a female. And then this archaeologist who, you know, he’s a scientist, not a feminist, he was just curious so he went back and did a meta analysis looking at a lot of other master hunter skeletons and found that 35 to 40 percent of them were women. And this is not to say that some people don’t object to his interpretation of these data, but to him, it made him reconsider the sexual division of labor. And that even though probably most early human women were breastfeeding and had a baby attached to them most of the time and couldn’t hunt, but that whenever they could, they did, and that it was more of a communal activity than we thought.

So I took that as, well, working motherhood is actually pretty standard. And in fact, when you then go on to early Western societies, those are working mothers. The housewife in the 17th and 18th centuries in America was working very, very hard, physically. And maybe the labor is divided by sex, and maybe the woman is more indoors and the man is more outdoors, not always but a lot of the time, but it’s still hard physical labor. And for women with enough wealth, they’re managing a staff in these early days of America, if they can. Or they’re doing everything themselves, and there’s no cooking that’s about making this glorious meal, it’s all about keeping people fed. And parenting in early America is about rearing children to be good citizens. The mom is not the center. The dad is the disciplinarian and the center of the family. And that really changes in the 19th century with what we call the cult of domesticity and in the Victorian era, where we start putting women on a pedestal and assigning this kind of umbrella of femininity around them of what that means. That they’re submissive, meek, compliant, and that they stay inside the home. So the more they’re relegated to the domestic sphere, the more they become the moral center of the family where they hadn’t been before.

And you see these waves over and over again. Every time there’s a war, the men leave, the women come out, we figure out that actually they can do physical labor, they can do management work, they can do all these things that are supposedly the province of men, and then the men return and find various ways of stuffing them back in to their domestic sphere. And you see it again in economic depression. For instance, if there’s a husband and wife who are both employed by the government and they need to make cuts, they lay off the wife first. And over and over again, there’s a concerted effort to determine what’s men’s work and women’s work based on the needs of the society at the time. But women never have any say in what that is. And I guess that brings us up to the Rosie the Riveter era when women went into the male workforce in droves, and all of these ways that they’ve been told that they weren’t suitable for factory work, the powers that be switched the messaging. So now your fingers are nimble from doing embroidery so you can transpose that onto the widgets in the factory. And that continues until the men come back for more again, and women are pushed back from factory work away from all of those men’s jobs.

And at the same time, you have all of that technology from the war, you have a housing crisis, you have a baby boom, and all of this leads to the growth of suburbia. And that’s really the first time that there is a complete separation between the domestic sphere and the vocational sphere, so that when you are staying home in suburbia, you are literally in another city, right? While the man gets on a streetcar and goes somewhere else, that’s the separation of the extended family. The nuclear version goes out and any kind of communal life falls away. And it’s also the beginning of this real discontent among those very women who supposedly have this new great life.

AA: One of the points that you make in the book at this point in the history, and then it’s brought up repeatedly later, too, is how America kind of latched on to this kind of renewed cult of domesticity in the 1950s and claimed that that was the way it had always been. And when we talk about it now with nostalgia, even with Trumpism and stuff, to make America great the way it was in the 1950s and always back into time immemorial, the traditional nuclear family household where the wife is at home. And you make the point that’s actually not the way it had been, it was kind of a new thing. Do you want to talk about that a little bit more?

we start putting women on a pedestal and assigning this kind of umbrella of femininity…they’re submissive, meek, compliant, and that they stay inside the home.

LSD: I think that that was one of the things that surprised me the most, was all this nostalgia for the traditional nuclear family when really that was a project of public-private partnership and the result of massive government subsidies. And they subsidize the mortgages, they subsidize the highways, there’s so much that went into the creation of these separate spheres where women stayed at home and men went off to work. And that got billed as the way always was. And it’s not to say that there weren’t echoes of that, right? It’s not to say that there weren’t women maintaining the domestic sphere, but when those spheres were separated, they weren’t necessarily separated by entire towns, right? One suburb, one city, et cetera. There’s still some overlap. And the other thing that interested me about early American families was just how much communal and community support there was. The involvement of churches and the government subsidies to move west with the railroad, there was so much institutional support for early American families.

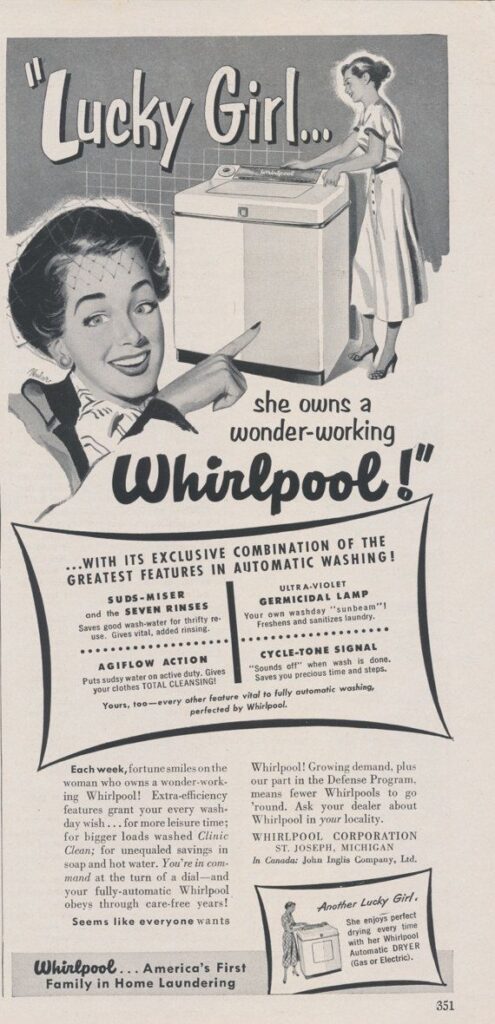

And I think part of what happens with this invention of the nuclear family, and that it should be these four people, or the married man and woman and the 2.6 children cordoned off in their little Cape Cod house, is that this really important aspect of familial life, which was that it was connected to the community, that falls away and the burden becomes more and more onerous and placed more squarely on the shoulders of the individual. You’re out there by yourself in your house, you’ve got your own washing machine, which in theory makes your life so much better. But now you’re not at the laundromat, or in harder times down by the river with a washboard and all the other women, you are alone. And the advertising is telling you your laundry isn’t good enough. Your whites aren’t white enough, your colors aren’t bright enough.

So there becomes this expectation to perform and perfect domesticity in a new way. And for this new middle class, right? So it’s not just wealthy people who have a team of underlings working for them to make everything look wonderful. It’s you in exchange for getting to live a little more comfortably, you have to somehow achieve those heights yourself. And I think it’s one of the reasons I’ve always had a visceral reaction to the suburban landscape. I’ve always felt kind of lonely in it. And this is why I was interested originally in the relationship between the built environment and architecture and community. As I thought, why do some places I feel so part of something and some places I feel so alone? I feel like the minute I step into that landscape, I pick that up. Even as I know that many people had incredible childhoods in suburban spaces and that there were lots of people who communed and that it wasn’t lonely for everybody. But certainly it was lonely and hard enough for many women that discontent became a phenomenon of its own eventually.

AA: Mm-hm. Let’s talk about that next, but really quickly I want to throw in another piece of equipment that you mentioned in the book that I’d never thought of. When you talk about every woman having her own washing machine so she’s not going to the communal laundromat, it was a lightbulb moment for me that that does just isolate her more. And then you said they’re not going to parks anymore because each family owns their own swing set in the backyard. That was really illuminating, a new thought for me in terms of, like I said, equipment. The isolated, fenced-in picket house that keeps these housewives very, very isolated and alone with husbands leaving all day. And that was the environment that I grew up in too. We lived away from both sets of extended family, we had a very strong church community, and thank goodness for that, because I think otherwise we would have just been adrift. But my mom was laboring with five kids, and my dad was gone a lot. And there is that American notion of independence instead of interdependence, and it’s not very healthy. It’s not the way humans are meant to live, right?

LSD: I don’t think it’s human at all. It is good for selling stuff, though.

AA: Haha, exactly!

LSD: I was having kids just as Amazon Prime was really gearing up, which was a terrible thing to happen at the same time. So I would just be like, “If I buy this, if I buy this…” I would never think, “Maybe I just need to buy less and spend a little more quality time, or have more boundaries, or do better at parenting.” I tried to buy my way out of it all the time because the cure for that kind of discontent is purchasing things. If your life is easier because you have this washing machine or a dishwasher, and it’s not taken up with this hard physical labor, well, then it’s a personal shame if you have spots on your glasses, right? I mean, I remember commercials like that, where the woman takes the glass out of the dishwasher and it’s streaky, and she has failed. And so she’s got to buy this thing. Because if she said, “Ah, I actually don’t really care.” If not, then there’d be nothing to sell her. So you’ve got to manufacture the discontent and then a product to solve that.

AA: Well, that’s something that Betty Friedan famously talks about in the book The Feminine Mystique, and she coined the phrase “the problem that has no name.” Do you want to talk about that phenomenon that grew out of the emotional despair of these women who are in their homes all by themselves?

LSD: Yeah. And I think one of the things that’s interesting and difficult and complex about women’s history is always, which women are we talking about? So, Betty Friedan was an upper-middle-class Jewish woman who was very smart and very well educated, and she was going to graduate school, I think in Berkeley, and doing very well. And her husband said, essentially, “You’re starting to outshine me so maybe you should quit.” And instead of divorcing him, she did quit. But then she was working on a survey for Smith, where she’d gone to school, and asked women about their lives. And she discovered all of these very well educated women who had become housewives in these suburban environments and were each miserable the way that she was. And eventually she turned that survey into the book The Feminine Mystique. And, of course, that chronicled the discontent of this particular class of women who had been educated and then had to tuck that education away. And I think to a certain extent, when you’re a housewife in that new era where you’re not doing hard physical labor or managing a staff, and you’re getting these messages that you’re doing it wrong but you’re not even sure what you’re doing, and you’re not sure why you’re feeling so bad about it, that’s a particular experience. I think a lot of women would have gladly traded to have that experience, and of course there were always women who didn’t have the luxury of not working. And I’m sure they had a problem that did have a name, which was like, “I don’t have enough money, I don’t have enough support. I’m married to a schmuck,” whatever it is.

But I think because she was chronicling the discontent of the kind of women who buy magazines, and she was a woman who wrote for magazines, and it was something that this media class could relate to, it was a very big deal. That is not what led to Second Wave Feminism, but I think it was a big part of it. Really pushing for women to have more choice about manifesting their own lives. Because these are women who in theory would have choice, who did have skills, who could have paid someone, for instance, to do childcare, and yet they didn’t feel like they had any options. And in a lot of ways, that movement accomplished a lot in that it normalized women going back to work, and it also did some important things that we rarely talk about anymore, like getting rid of marital rape laws that said it wasn’t rape if you were married, et cetera, and single women couldn’t have bank accounts in their own name. All kinds of structural ways that women could not achieve financial independence. And the women’s movement really worked hard at pulling those things back and allowing women to flood out of the domestic sphere should they choose to. And that didn’t necessarily work out exactly the way we would have wanted it to.

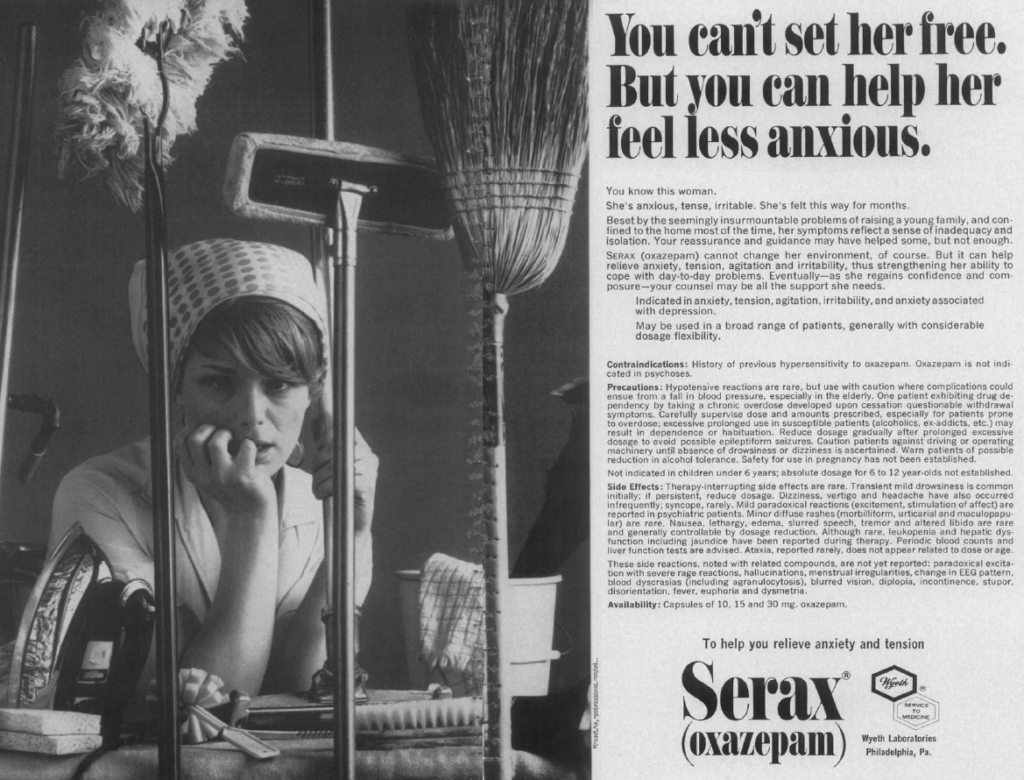

AA: True. Before we move on to that next chapter about women getting out into the workforce and then encountering a new set of problems, I want to drop in to your chapter about the medicating the housewife. Because that was another one that was totally new to me and I was riveted and also horrified. Can you talk about the ways that housewives were medicated during this era?

the woman takes the glass out of the dishwasher and it’s streaky, and she has failed…

LSD: I cannot recall how I stumbled upon this information about lobotomies, somehow I was randomly poking around looking at lobotomies, and I discovered that Walter Freeman’s first patient was a housewife. Freeman did not invent lobotomies, but he imported them from the Portuguese doctor who did invent them and who won a Nobel Prize for it. And then he modified them and they eventually turned into the ice pick lobotomy, which was to stick an ice pick behind the eye and wiggle it around. The strange thing about lobotomies was that some people were quite happy with them, which we often forget. Because when they were performed on people who were truly psychotic and who had to spend most of their day in a straightjacket locked up somewhere, to be lobotomized, maybe drooling slightly in a corner, was better.

But they were also performed on people who were mildly discontented in other ways, and they were also performed on women who just weren’t doing motherhood or womanhood correctly. Who weren’t feeling affection for their children, for instance, and some of those women today we probably diagnose with postpartum depression. So they were obviously a complete inexact science, if we can even call them science, because you’re sticking an ice pick behind someone’s eye and wiggling it around and pulling out a little core of brain tissue. And they were also doled out disproportionately to women, even in mental institutions, where far more men were institutionalized than women. And there were women who were too sexual who got them, et cetera. So some of it was a kind of normalizing technique for people who were not performing their gender role properly.

And then I discovered that Freeman’s last patient ever was also a housewife, and that just fascinated me. This woman was actually on her third lobotomy, because some people had repeats, they went in for a tuneup. She ended up dying on the table and Freeman’s license was revoked, and that’s how lobotomies ended, really. It was not that they were ever banned, it was that they went out of fashion and the few people who performed them would lose their hospital privileges when things went horribly wrong. Although Freeman also drove around in a truck he called the Lobotomobile, which is so wild. I feel like somebody should be the Lobotomobile for Halloween. What a costume.

AA: Haha, totally.

LSD: What really ended the lobotomy era was not that people said, “Oh no, this is so terrible! We have to stop doing it.” I mean, there definitely were people saying that, but that’s not how it ended. It ended because of the invention of pharmaceuticals, and especially sedatives and classes of drugs that knocked people out without having to stick an ice pick in their eye. And those two, most famously Valium, were disproportionately prescribed to women and still are, you know, antidepressants are disproportionately described to women. A lot of that is for the same set of reasons. But I write in there about some other ideas about what that is and why that is. So some of it could be that we also learn to talk about our feelings a lot more than men and thus it may seem like we have more emotional problems. They may be expressing their discontent or upset in different ways or not using emotional language to describe it, so they might not get a prescription for a psychiatric medication as readily.

But I also think that there’s a long history of diagnosing women with hysteria. It was the most popular diagnosis for decades and decades. And in some cases, sure, a woman was not able to function. But in other cases, she was just too emotional for the pleasure of the people in power in one way or another. And so these drugs, especially Valium, were really heavily prescribed to these unhappy housewives, so much that the addiction was called housewife’s disease in some cases, and they became addicted in huge, huge numbers. And then there were a number of congressional inquiries and documentaries, and a generation of women who didn’t like their lives got hooked on these drugs.

AA: Yeah, it’s really, really tragic. I’m trying to remember an illustration in the book.

LSD: There were amazing ads, amazing ads.

AA: That’s exactly what I was thinking of. I just found it. It says, “You can’t set her free, but you can help her feel less anxious.” And it shows this woman with a mop, a broom, a duster, every cleaning implement, and she just looks miserable. Again, “You can’t set her free, but you can help her feel less anxious.” So this is obviously marketed to people’s husbands, the husbands of depressed wives. So, let’s not examine why she’s feeling depressed, let’s just medicate her. That’s really crazy to me.

LSD: Yeah, let’s not think about a fairer division of labor, she’s still got to scrub the bathroom, but you can make her stop complaining about it if you give her this drug.

AA: Woo! Yeah.

LSD: I feel like my husband will be like, oh wait, is there a drug I can give you to stop this thing?

AA: Haha. Oh man. Okay, well let’s move on to the next period. Because as you say, as we move into the late ‘60s and ‘70s, things do start to change. Can you talk about those changes and what that then meant for women?

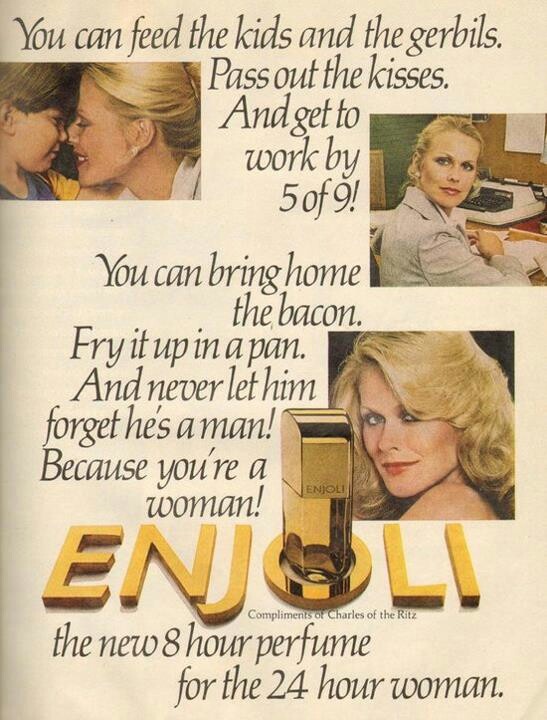

LSD: Yeah, there was massive cultural change where all kinds of women went to work, not just the women who had to, and the archetype of the career woman emerged. And from there, we kind of went to the super-mom. So, there was a massive amount of cultural change, but some big things didn’t happen through second-wave feminism and didn’t happen in the 70s, mostly in terms of not passing childcare bills and family leave bills and not really setting up an infrastructure so that both parents could go to work. So now we don’t live with our extended family and nobody’s home, right? And you either have to figure out how to pay for childcare or make a choice, and again, it’s all on the individual family. Because we’re radically changing the way we live, but not creating any more support for it. And there’s no more dominant culture, so with each iteration it’s sort of more on the individual woman to figure out how to navigate this. And I think it leads to the next wave of women feeling inadequate.

And I talk about this commercial, I think in the very beginning of the book, that is absolutely imprinted on my brain for Enjoli perfume. And it shows this woman, and they rehash this 1963 Peggy Lee tune, ‘I’m a Woman’, and it says, “I can bring home the bacon, fry it up in the pan, and never let him forget he’s a man.” So they show three of her, she’s the same woman fractured into three parts: the cooker/cleaner lady, the boss lady, and the sexy lady for her husband. And it’s perfume for the 24-hour woman. But there’s no sleeping, there’s no getting any exercise, there’s no reading a book. Where are the kids during the day while she’s at work? So it presents this model of modern womanhood, which is totally impossible to attain because nothing else has changed in our society and the women are still expected to do just as much housework. Especially in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, it’s a long time before that leaks out into men’s work and that it becomes normalized for men to do childcare and change diapers, et cetera.

So there’s this whole decade of “you have to do everything,” and then there are kids like me whose moms are gone. There’s a huge amount of divorce in the ‘70s because women were like, “I’m working and I don’t need to rely on my husband for money.” So then you’ve got these kind of unparented children, and many of them like me hardly knew any married parents. And you’ve got a world in which so much changed and so much stayed the same at the same time. And I think we never really got beyond that in some ways. I think we’ve been going around and around in the problem with no name over and over again. Because I don’t think we ever addressed what still needed to happen, and that’s largely because we fight about what the family should be and what women should do. We don’t have a country that’s unified around choice. We don’t have a country that says let’s do what we need to to have the strongest and healthiest families, whether there’s a single mom for whatever reason, or there are two parents and they’re both working, or somebody wants to stay home. We’ve left it up to the individuals to figure it out, we’ve privatized industries like childcare. It’s very hard to figure out how to navigate your own path because everything is what works for you and there are constant messages about what you should and shouldn’t be doing. I mean, our national pastime is judging people for their parenting, right?

AA: True.

LSD: You’d have to really be self-possessed to be unaffected by that, which I am not. So I kept thinking I was failing over and over again. I think the pandemic changed that in a whole host of ways, which we can talk about. But I also feel like, for me, one of the things I realized is that if my kids are okay, they’re growing up and we have enough money to feed them, we’re fine… We’re fine. And fine is great. My kids are, knock on wood, doing perfectly fine. But I’m in a culture where they’re supposed to really succeed. They’re supposed to be professionalized and really great at two to three things, have mastered the trombone and do semi-professional gymnastics by age 12. And so I actually think you have to learn to push those messages away. If those messages don’t energize you, if they just overwhelm you, then you have to get rid of them and think, what do I want for my family? And what do I think is best and healthiest?

AA: Well, you mentioned the pandemic, and let’s talk about that because I feel like that did bring up some of the issues that maybe we were all just too busy and stressed out to actually talk about it. And some, having the pandemic totally changed things, really brought to the foreground some of the inequities that were there. Do you want to talk about that for a minute? I think it’s really important.

LSD: Yeah. I think it was the first time that we admitted that moms were the social safety net, and we saw millions of women forced to drop out of the workforce to take care of their kids. And the women who couldn’t afford to do that had to give up on their kids’ education. And there was this huge reckoning, and there was space devoted to it in the media. People seemed like they actually cared. I don’t know how much that ended up being sustained, and I’m not sure it led to the structural change that we needed fifty years ago, because we don’t have universal daycare or family leave or better wages or a lot of those problems. They got a lot of attention, but they didn’t translate into policy again. I think that at the time it felt really important to a lot of us, like I’ve been walking around and feeling like I am doing everything and I’m failing at everything, and I don’t know how to enjoy my life even if I realize that my life is pretty good. And it seemed like, great, we’re going to talk about this now. And we did. And for some people, myself included, even though it was really hard and even though we knew that some people were having just unbelievable hardship, for us, in my family, it was a little bit of a reset. My husband was around more and furloughed one day a week, he could do more of the cooking and could be more involved. And we’re very lucky, it ended up being really good for my marriage. And other people were stuck in the same house and realized they didn’t want to be married, or just had terrible things happen and didn’t have enough money and didn’t have enough food. I know there was a lot of hardship, so I don’t want to gloss over that, but I think the reset was important. You said it changed your life.

AA: Yeah, we moved. It totally unsettled all kinds of things. Writ large on the national scale.

LSD: Was there a shift in your division of labor and how your family ran after that?

AA: Not for us, because my husband actually has always worked remotely long before the pandemic. So it actually didn’t change our particular situation except that the kids were home, but they were also a little bit older and more independent. But it was interesting to watch all of our friends, like, “Ahh, we’re both home!” and having to make those decisions, so it was really interesting for us.

LSD: It seems to me that that moment of caring about the experience of modern motherhood faded and not much happened. And I think what you’re seeing now with my book and a few other books coming out is this kind of post-pandemic literature of looking at economic inequality, looking at structural inequality, but in a personal way. That sounds very academic, you know, but looking how we got there. I don’t want to be too negative, but I feel like we didn’t change the way that I hoped. And now we are so polarized as a nation that bipartisanship is seen as treason. So coming together to strengthen the American family, you know, I envision this whole host of policies that you put under that banner so that both sides can invest in it, but right now they just want to destroy each other instead of actually making things better for people. So, I am a little saddened that we didn’t make more changes when we could and that we still are rooting these things in the culture instead of in the structures that power the culture.

AA: Mm-hm. I agree. That’s a really good point that I hadn’t thought of in those terms. That there was more solidarity and unity especially in the early days of the pandemic, and we did kind of open our eyes and talk about structural inequities, we gained a vocabulary for it, we started noticing things, and everyone seemed to be on board. I view that as a positive. At least we have more language that’s common in the public discourse to at least describe it and know that it happens. But I think you’re right that I feel really discouraged also by the partisanship and by the tenor of the national conversation right now. We’re in a difficult moment to try to make any structural changes. I wish we could have acted on it while we were all feeling kind of on each other’s team during that minute in 2020. It would have been easier to do that.

LSD: We’re still back to fighting about who’s supposed to do what and whose responsibility is it, and not in a way that people listen to each other and think, “Interesting, let me ponder that for a minute.”

AA: Yeah, but to actually do something about it. Well, if we can shift for a second to what we were just talking about in terms of polarization, there’s a recent development that feels to me kind of like a pendulum swing and a bit of a backlash against the super-mom, and that’s the tradwife phenomenon. I was hoping when I saw the title of the book, Housewife, I thought, “I hope she talks about tradwives,” because that’s been keeping me up at night for the last few months, puzzling over this. I admit that I think part of why I get– I know the term “triggered” is way overused, but I do actually get triggered by it. And I think part of that is because that’s very much how I was raised, to be a traditional wife that is only home with the kids, loves to do all of the traditional tasks that go along with that, to always look beautiful and have a beautiful home and have beautiful, well-groomed children. And the fact that I ideologically have big problems with a lot of that, but that that’s how I was raised just leads to all kinds of internal dissonance for me when I see these tradwives’ accounts. So I’d love to hear what you think about it, but maybe also to share some of the anecdotes that you talk about in the book. Some specific examples of women making these choices and then later being like, “Oh crap, I didn’t think of what might happen.”

LSD: Well, everything I had read had already told me that they were racist, white supremacist, anti-feminist, hateful, and horrible. So I went in there expecting to find that. And of course there are people who label themselves as tradwives and who fit that bill, but I actually found quite a few other people. The most prominent tradwife is a woman named Alena Kate Pettitt, who’s British and grew up in the ‘90s, and said that she was kind of beat over the head with ‘90s girl power, which was sexpot feminism, Spice Girls. And it was kind of just another iteration of the Enjoli perfume, really, because it was like, you have to be really hot and kick ass, be a boss lady, a career woman, and maybe the only difference is you sort of prioritized friendship as much as having a boyfriend. What’s the famous Spice Girls song?

AA: If you wanna be my lover, you gotta get with my friends.

LSD: Yes. So, female friendship is kind of on par with the relationship. That’s the only big difference.

AA: That’s funny.

LSD: She was always asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” And she wanted to be a wife and a mother. That was her aspiration. She’d look around, and it was very clear that she was not to say that. That was a shameful aspiration or lack of aspiration. So when she grew up, she found someone who wanted that life too. And she gave up her career in marketing and had a child and stayed home. Her husband takes care of the money and takes care of the house, and they have a very “traditional” sex-based division of labor, and she’s very happy. Now, there are a few odd things about it, for sure. The first is that you really leave yourself incredibly vulnerable financially if you give up your job completely and you give up your future earnings. If you are not ensuring that you definitely get half of the money forever, then you could really end up being screwed over. And I did interview a lot of women who did something very similar and ended up with nothing. It was incredibly difficult.

The other thing that I think is odd is that Alena Kate Pettit in particular talked about Doris Day as her patron saint, but Doris Day was actually a full-time actress. She was married four times to often abusive and controlling men and was zero percent like the character she portrayed. So they are romanticizing a fictionalized version of traditional families, which you talked about in the very beginning. And I think they even talk about some of those shows, like I Dream of Jeannie or at least Bewitched, and it looks like this beautiful, perfect family, but really it’s about neutering powerful women. So I found that very odd that the “trad” in tradwife is mostly a fiction. However, I think that they have a much fairer division of labor than the vast majority of women, who do way too much. And this is one way to have an equitable division of labor. I think the reason it riles up so many of us is that it is a sex-based division of labor. And most of us either don’t do that or we pretend we don’t do that.

AA: Ooh, interesting. So it’s triggering everybody, but just in different ways based on what they’ve chosen to do and what they’ve repressed or what they’re pretending. That’s very interesting.

LSD: For instance, in my liberal Brooklyn neighborhood, no one is saying, “I do the cooking because I’m a woman.” They might say “Women, we do it all.” But they don’t understand, unless they’ve read this book, exactly how that happened. They haven’t made decisions like, “You’re going to balance the checkbook because you’re the man,” because that harks back to the idea that men are good with numbers and women can’t do math. It brings up all of these ways that women have been oppressed. So I think it’s very frightening for a lot of women. And yes, to me, it is a little bit odd. The millennials I interviewed were dividing things based on skills and interests, not on sex, and some of those things fell along sex lines and some of them didn’t. There were a lot of men who liked vacuuming and cleaning the bathroom. And my husband was the diaper-changer-in-chief and now he does the cooking. That’s post-pandemic. So we don’t make decisions about labor based on sex, but a lot of us, when we look around, it seems like it worked out the same as if we did. It still looks like the Enjoli commercial or some version of Spice Girls except not hot, you know? Not hot, not rich. I think that’s why it’s so triggering.

AA: That’s really interesting. Okay, Lisa, we’re almost to the end of our time, but I wanted to squeeze in one last question if we can. There was a chapter on the First Lady of the United States, and I had never, ever thought about it, but this is the housewife writ large, right? Could you talk about the First Lady and her role just for the last few minutes of our episode today?

LSD: The First Lady is the ultimate in unpaid labor. Officially, she’s the hostess of the nation, but she’s really the housewife of the nation. There’s no official role for her, it’s not written into the constitution. So in the early days of this country, the wife was the social lubricant. She’s throwing parties, if the person who’s running for president, like James Madison, doesn’t have a lot of social graces, Dolly Madison is doing all the behind-the-scenes stuff. Some of these eventual First Ladies are the ones who decide you’re going to be president. And Dolly Madison was really the first to associate First Ladies with a series of responsibilities. Again, it’s not written down anywhere, it just became custom. So they have their causes, like literacy or girls’ health, whatever they decide. And then they have all of these ceremonial duties and ribbon cuttings, and they have to show up everywhere, they have to stunt for their husbands. And weirdly, even though they’re married to the guy, they’re seen as kind of morally pure, and they’re not infected with the partisanship because they’re not actually politicians. So they do all of this work, they lay all of this ground for this huge political machine, and they are literally the only person in the east or west wing not paid. They often work from 6:30am to 10:30pm or even later. Even the interns are paid now.

the reason it riles up so many of us is that it is a sex-based division of labor. And most of us either don’t do that or we pretend we don’t do that.

And a lot of that rests on the fact that we expect the wives to do this work. And no one has ever figured out how to possibly compensate her because she would be tainted, she would be an employee, nor how much. But there have been some estimates that anyone who worked a job like that, where you work these incredibly long hours, you have all of these responsibilities, you have to have both vision for what could happen and manage a staff to make it happen, that you would make maybe $250,000 to $350,000. But you make $0. And in fact, you’re not even allowed to keep your gifts. I mean, you can keep them, but you have to pay the taxes. You have to either buy your own clothes, or if they’re given to you, you have to give them back or pay taxes on them, so you can’t actually accept anything free. You cannot be compensated in any way for far more than full-time work for however many years your husband is in office. It’s wild, right?

AA: Yeah, totally wild. And I also loved how you did lay out some of their duties, like they are supposed to, and it’s just custom, I guess, but they have to choose the china pattern for the different state dinners. They have to decorate the White House for Christmas, whether or not they’re interested in that stuff. But it’s so traditionally gendered. And you said, what will happen when the first woman is elected president? I think that’s going to be what it takes to change things, right? Is having the man in there and deciding whether he wants to pick the china.

LSD: Well, when Hillary Clinton was asked, you know, “Is Bill going to pick the china?” She said, “Well, I will negotiate with China and I will pick the china.” So she was basically like, “I will do both roles so that I don’t have to emasculate my husband, the former president.” So it will be very, very interesting to see what the First Gentleman does.

AA: It would, you’re right. And the public conversations, so much of it is also about what you look like. What they’re wearing, their hair, just nitpicking every little detail about their physical appearance. So yeah, that will be fascinating whenever that happens. If it ever manages to happen in this country.

LSD: I wonder. It will be interesting to see what goes on in the next couple of years and how much we consider women’s work and women’s roles. And even more importantly, how we consider creating a society that makes these strong and functional families as we go forward.

AA: Yeah. Well, Lisa, this was an incredibly informative and delightful conversation. I’m so grateful that you were able to join us today. Thank you for your book. Again, it’s called Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All and What to Do Instead by Lisa Selin Davis. Listeners, go grab a copy, read it, buy extras for your friends, and pass it around. Lisa, thank you so much for being here.

LSD: Thank you, that was really fun. I really enjoyed it.

you’ve got to manufacture the discontent

and then a product to solve that

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!