“as one of us speaks out, others will join”

Amy is joined by Dr. Michael Kaufman & Dr. Michael Kimmel to discuss their book The Guy’s Guide to Feminism and share the how men can overcome discomfort and guilt to become true feminist allies.

Our Guests

Dr. Michael Kaufman & Dr. Michael Kimmel

Michael Kaufman, PhD, is a writer of both fiction and nonfiction books. As an advisor, activist, and keynote speaker, he has developed innovative approaches to engage men and boys in promoting gender equality and positively transforming men’s lives. Over the past four decades, his work with the United Nations, governments, non-governmental organizations, corporations, trade unions, and universities has taken him to 50 countries. Michael is the co-founder of the White Ribbon Campaign, the largest effort in the world of men working to end violence against women. And he wrote the training program on sexual harassment used by tens of thousands of staff at the United Nations.

Michael Kimmel, PhD, is one of the world’s leading experts on men and masculinities. He was the SUNY Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies at Stony Brook University. Among his many books are Manhood in America, Angry White Men, The Politics of Manhood, The Gendered Society, and the bestseller, Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men. With funding from the MacArthur Foundation, he founded the Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities at Stony Brook in 2013. A tireless advocate of engaging men to support gender equality, Kimmel has lectured at more than 300 colleges, universities, and high schools. He has delivered the International Women’s Day Annual Lecture at the European Parliament, the European Commission, and the Council of Europe, and has worked with the Ministers of Gender Equality of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden in developing programs for boys and men. He consults widely with corporations, NGOs, and public sector organizations on gender equity issues. He was recently called “the world’s most prominent male feminist” in the Guardian newspaper in London.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: As I do the work of breaking down patriarchy, one of the questions I get most often from women is: “How do I talk about gender inequity to the men in my life? Any time I bring up the ways that I’m hurt or frustrated, they get so defensive. The conversation goes terribly and makes me not want to talk about it ever again, which means nothing ever gets better.” I also sometimes have this experience with men even when I work hard to couch my thoughts and my feelings in non-threatening “I feel…” statements, and I pour on the benefit of the doubt and offer one million reassuring caveats, I’m still quite often met with a lot of denial and defensiveness. And this is discouraging not only on a personal level, but also on a societal level. We need cisgender male allies in positions of power, because in many cases still, only cisgender males have access to the levers of power that affect the rest of us.

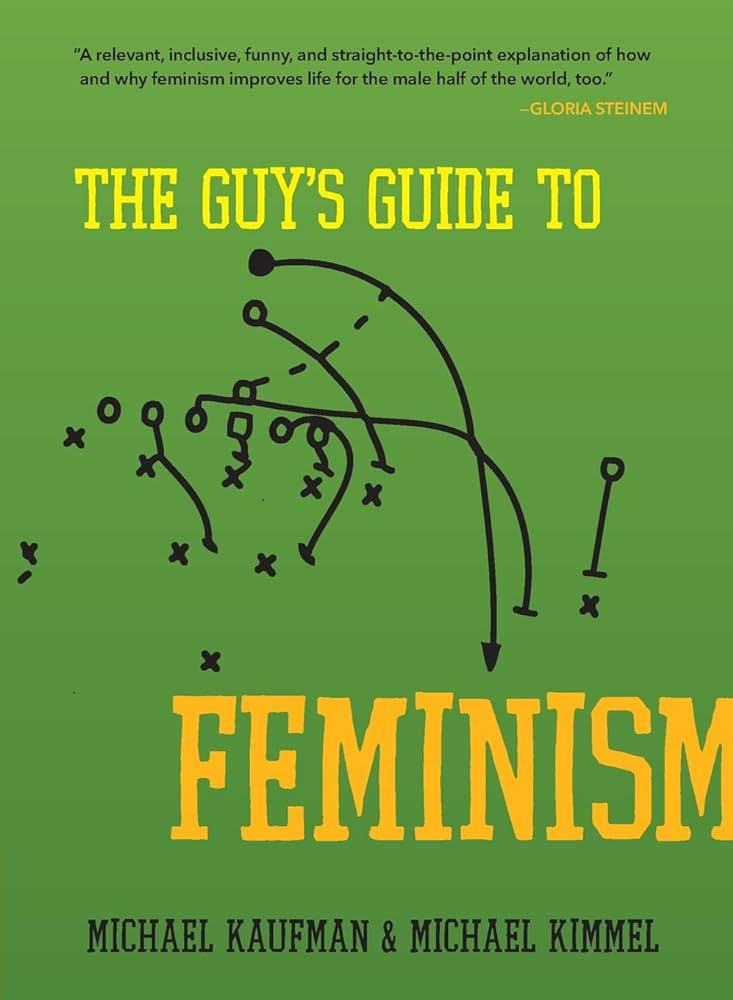

So, who are the men out there in the world trying to educate other men about gender equality? The first thing I thought of was a hugely influential TED Talk that I’ve mentioned multiple times on the podcast called “Why Gender Equality is Good for Everyone, Men Included”. This TED Talk is by Dr. Michael Kimmel, and it’s where I learned the phrase “privilege is invisible to those who have it.” You can imagine my excitement, then, when I discovered that Michael Kimmel had written a book with another hugely influential activist for gender equality, Dr. Michael Kaufman. Their book is titled The Guys’ Guide to Feminism. I read the book in preparation for this episode, I loved the book and I’m so excited to discuss it today, and thrilled to welcome to the podcast Doctors Michael Kimmel and Michael Kaufman. Hi, Michaels!

Michael Kaufman: Hello!

Michael Kimmel: Hi! Great to be here.

AA: So excited to have you here. I’ll quickly read a very, very abbreviated version of your professional bios just so listeners know who you are.

Michael Kaufman, PhD, is a writer of both fiction and nonfiction books. As an advisor, activist, and keynote speaker, he has developed innovative approaches to engage men and boys in promoting gender equality and positively transforming men’s lives. Over the past four decades, his work with the United Nations, governments, non-governmental organizations, corporations, trade unions, and universities has taken him to 50 countries. Michael is the co-founder of the White Ribbon Campaign, the largest effort in the world of men working to end violence against women. And he wrote the training program on sexual harassment used by tens of thousands of staff at the United Nations.

Michael Kimmel is one of the world’s leading experts on men and masculinities. He’s the SUNY Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies at Stony Brook University. Among his many books are Manhood in America, Angry White Men, The Politics of Manhood, The Gendered Society, and the bestseller, Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men. With funding from the MacArthur Foundation, he founded the Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities at Stony Brook in 2013. A tireless advocate of engaging men to support gender equality, Kimmel has lectured at more than 300 colleges, universities, and high schools. He has delivered the International Women’s Day Annual Lecture at the European Parliament, the European Commission, and the Council of Europe, and has worked with the Ministers of Gender Equality of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden in developing programs for boys and men. He consults widely with corporations, NGOs, and public sector organizations on gender equity issues. He was recently called “the world’s most prominent male feminist” in the Guardian newspaper in London.

These are amazing, impressive professional biographies and I’m so grateful for your work, both of you. I wonder if you could start us off by telling us a little bit more about yourselves personally and what brought you to do the work that you do.

M. Kaufman: Michael, do you want to jump in first?

M. Kimmel: Let’s start alphabetically, man.

M. Kaufman: Okay, haha.

AA: Love it.

M. Kaufman: Well, for me, a lot of it goes back to growing up in the U.S. South. I live in Canada now, but I grew up in the U.S. South in the 1960s in the midst of racial segregation. And my parents had a basic rule. We were white, but they said we would not go to any establishments, any theaters or restaurants that were racially segregated. And as a little kid, I said, “Why, why can’t I go? All my friends are going.” And they said, very simply, “As long as everyone can’t do that, we can’t do that.” And I got beat up for my beliefs. I learned very early on that you should take sides, but I also learned early on that we had to not just think about ourselves and our own well-being, but that of others.

And I ended up at university in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, and all my women friends were feminists and they began to challenge me. They began to raise questions about things that I said, things that I did, and it felt incredibly uncomfortable at first. But by and by, I thought I was very quickly, you know, one of the good guys. And I say that sarcastically because I didn’t actually think about my life as a man. I knew that like most other men, the expectations placed on me, the demands never felt totally comfortable, but, you know, I got by pretty well.

And it all changed when I ended up by chance in a men’s discussion group. And I went into this group and I looked around at the other men and I thought I had them all pegged. This guy was the jock, this guy was a successful businessman, this and that. And I just felt I have nothing in common with any of them. As soon as we opened our mouths, we all said the same things. We all were sympathetic to the struggles that women were going through and a surprise to me was none of us felt comfortable with this sort of straitjacket, the suit of armor that men were expected to wear. And that began a process for me in the early 1980s of not only thinking about how I could support women’s rights, but also what that meant in terms of positively transforming the lives of men and boys.

M. Kimmel: I’ll jump in now with pretty much the same trajectory, having not grown up in the American South. But quite seriously, the ideas of feminism, the ideas of gender equality were swirling around colleges and universities in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, and I was swept up in some of that as well. Particularly, I was in the first co-ed graduating class at Vassar College in 1972, and I was very shaken by a lot of the feminist ideas that some of my friends were talking about. And of course, as Michael said, I didn’t think they had very much to do with me. So one could easily nod in approval and say, “Oh yeah, that’s right. That’s cool.” But it seems to me that just as Michael said for him, it wasn’t until graduate school when a bunch of men got together at Berkeley, where I was doing my PhD, and said, “Gee, these women are doing all these amazing things, and they’re having these consciousness raising groups. Maybe we should have one too.” And so we got together.

But unlike Michael, mine was a disaster. Because all we did was kvetch. You know, women would go into a consciousness raising group and say, “Gender equality affects me in this way and this way and this way,” and so it’s personal as well as political. And the men would go in and go, “Boy, nobody understands me. My wife doesn’t understand, my girlfriend doesn’t understand me. All the pressure on me. I have it so bad.” And there was something so inauthentic about that for me. I felt like, “Wait a minute, if all we’re going to do is complain about how hard it is to be men when we occupy 97 percent of all of the positions of power in the world, there’s kind of a disjunction here, and we have to start taking it on.”

So, I left that group and started thinking about how I could contribute to gender equality by talking to other men about these kinds of issues. And over the years, that’s basically what I’ve done and what Michael has done, is try to find ways that we could talk to men about these issues. Because I have to say, our experience, Amy, is exactly what you described in your opening remarks. So many of the women in our lives come to us and say, “Every time I try to talk about this, the guys get really defensive. They take it really personally. I can’t get anywhere.” So we decided to write this book for that very reason. We said, “Okay, guys. We’ve got to talk about this.” And we’ve got to talk about this in a way that is not threatening, that is not scary, but in fact makes the argument that both Michael and I spent 30, 40 years stumbling toward. Which is, as I said in my TED Talk, that gender equality is good for everyone. It’s actually good for men, good for our relationships, and politically, more gender equality, and in corporations too. And so that’s where we started. That’s why we did this book, was to precisely address that very question that you posed in the beginning.

AA: Fantastic. So I’m wondering how it was received when it was first published. What feedback did you get from men?

M. Kimmel: Haha. Good question!

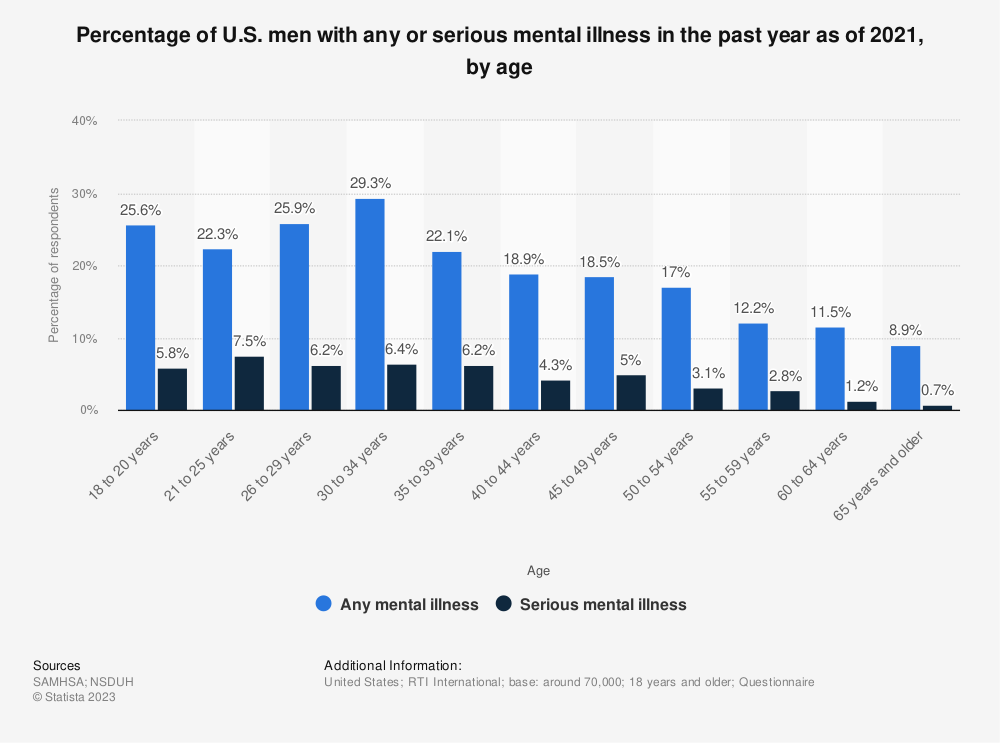

M. Kaufman: Well, I mean, there were millions of men running hysterically through the streets waving our book in total joy that finally something spoke to them. I think one of the things that we can both say, and both Michael and I continue to have the experience. Back in the days when we actually spoke to live audiences, we’d often have the experience of looking at the men coming into a hall of 100 people, 50 people, 1,000 people, and many of the men would be, you know, with their arms crossed and leaning away from us. And just the look on their face was, “Okay, I know I’m just going to be dumped on for the next hour, but I’m going to endure it.” Instead, we tell stories about both the forms of privilege and power that men enjoy, but also the ways that we’ve constructed this world of men’s power brings hardships to men ourselves. Men struggle to fit into these expectations. And that struggle we see manifested in these realities in men’s lives. Men are more likely to be addicted to alcohol and other drugs, men are more likely to take our lives by suicide. We die younger, we’re less likely to ask for help for health reasons, for mental health reasons, and on and on because we constantly have to prove that we’re real men.

And as soon as we start telling these stories about the lives of men in the framework of basically being positive about feminism, we look at those men in the audience and we watch them relax. We watch them nod in appreciation. Because for the first time in their life, they’re hearing an authentic conversation about men’s lives. It’s like we’re holding up a mirror to them. So I think that one of the things that’s been so rewarding that Michael and I have often talked about over the years has been that reception by men as they hear with openness and love in their hearts and minds to a critique of patriarchy and of the oppression of women. But also critique of the expectations placed on men and the positing of an alternative that they can embrace.

It’s actually good for men, good for our relationships, and politically, more gender equality, and in corporations too.

M. Kimmel: Amy, you asked the question of how it was received and Michael’s response was, you know, how it was received by other men. And while I wish that it would have looked like a rally for the Chinese Communist Party in the 1960s where everyone was holding up their little green book, I have to say that since about 75 percent of all books in the United States are bought by women and about 95 percent of all books about relationships in the United States are bought by women, the reaction was really interesting. What we heard anecdotally was that a large number of women were telling us that they were buying our book as a stocking stuffer for their boyfriend at Christmas time.

AA: That’s awesome.

M. Kimmel: They were buying it for the guys that they knew. It became a kind of gift like, “Here, dear, you should read this.” And I found that to be fascinating because I think that what we tried to do was to say, listen, guys, all of that stuff that you say about men’s power, the privileges that we have, the defensiveness you hear. Michael’s right! You want to say, “How’s that been working out for you, fella?” You know, we keep reading about deaths of despair, the amount of despair and pain that we hear constantly. And distress from men in the industrial world, everyone is talking about it, including the far right. And in fact, in a moment where men are beginning to be acknowledged for the distress and depression and sadness and grief and anguish that they’re feeling and all of the different symptoms of that, we have a lot of false prophets running around saying, “Okay, guys, here’s what you have to do. Follow Jordan Peterson, follow Josh Hawley, follow Andrew Tate,” you know, follow all of these false prophets of masculinity rather than listening. If you feel upset with things as they are, why not survey and take a look around and see who else is upset with it, and make an alliance with them. It’s really easy. You feel bad that you’re hemmed in by what you consider your role? Okay, who else might be feeling that way? Let’s talk. So I think that was the idea behind our book was to say, guys, this whole idea of gender equality, this is not taking place somewhere else. We are stakeholders in this conversation. This is about us.

AA: Well, that’s one reason why I was so grateful, honestly, that the book was written to men by men. Because I’ve been reading a lot too, I don’t know if you both read the article by Christine Emba in the Washington Post this past week about that very thing, right? That oftentimes in the left of center, I guess, or the centrists, are not articulating an alternative that’s appealing to men. And so these really conservative and misogynist men have an opportunity to assert their own ideas. And they’re in the vacuum so they can indoctrinate, especially youth are susceptible to that. So I appreciate the positive and proactive assertion that it doesn’t have to be this way and we can relate to all of these things, and then positing a new and better way for men.

I also noticed the tone of the book. It’s very conversational, it’s casual, it’s funny. I mean, even on the cover of the book there are kind of like football plays and I really loved that. I wondered if you debated between different approaches in terms of tone and target audience. And who were exactly the men that you were trying to reach? Why did you choose the tone you did?

M. Kimmel: Let me take this one. First of all, we never debated this. We always knew it had to be light, conversational, and as you said, funny. Because both Michael and I use humor in our work quite strategically. You remember when Michael was describing the audiences earlier and he said that these guys come in and they’re leaning way back and their arms are folded across their chest and they’re thinking, “Okay, some woman is going to come out here and yell at us that we’re the problem for an hour. I have to endure this and then I can get back to work.” And so we know that people come in as you do, Amy, as your opening comments mentioned, we know that people come in defended. They think they don’t want to hear this.

Now, what humor does, and particularly the kind of self-effacing humor that both Michael and I use– Basically, if you laugh you exhale. You don’t have to hold your breath anymore. You loosen the tension in your body, your arms unfold, you lean forward. In other words, laughter, humor is a way to engage people. It’s not scary. And then in that moment, you’re open to hearing the reality that all of the data suggests this is a good thing. This is not a bad thing. And I’ll just say one thing about this. Guys know this! This isn’t rocket science. Everybody knows this. You want to meet a male feminist? Talk to a guy whose daughter just hit puberty. Because he’s gonna say, “Oh my god, there are boys looking at my daughter the way I was taught to look at girls. This has got to stop right now.” Right? He’s a feminist at that moment. Everybody knows what it feels like to love women and want them to thrive. Everyone. All the men know this. All we need to do is remind them. It’s not a matter of teaching you something new, it’s reminding you of something you already are doing.

AA: That’s awesome. Any thoughts from you, Michael Kaufman, on this before we go on to the meat of the book?

M. Kaufman: I think just to stress to people that we wanted to write a book that was really, as Michael said, fun, that’s really accessible, that’s short, that’s pithy, that you can just jump into and jump out of the different pages. You don’t have to read it from the front to the back or the back to the front. And just to make it really accessible and light and engaged in a series of key issues and topics.

AA: Well, I thought it was completely successful on all of those points.

M. Kaufman: Thank you.

AA: I really, really enjoyed it. Oh, I’m planning to give it to so many people. I have a 15-year-old son right now and he has three sisters and he’s a budding feminist himself. But I thought there are so many issues in here that we haven’t talked about explicitly, so he’s going to be the first one to read it and then my husband. And then we’re giving it to lots of people. But I thought it was fantastic. Like you just said, I did love the format of each topic being just a couple of pages. You can skip around, you can read it in small doses or you could sit down and read the whole thing. I actually dog-eared some pages that I’d love to hear you talk about. The book is organized alphabetically by topic, and I also loved that format. I thought that was a really great, clever way to do it. Maybe I can just give you one of the main points and then you tell me why it’s important. Does that work?

M. Kimmel: Sure. I mean, the alphabetic thing was deliberate also. What we brainstormed was, okay, what are all the issues that feminist women have been trying to say to men? Like, “Hey, talk about this. Hey, deal with this.” So we made a big list and then we said, let’s do it alphabetically just to make it even more accessible.

AA: Love it. Yeah, I thought it worked great. There were a lot of A’s, I noticed, and it was really hard to choose between them because I had a lot of underlines and dog-ears in the book, but we’re going to start with Ally. That’s the very first word in the book. And you write that the dictionary definition is one, “to unite or form a connection,” two, “to enter into an alliance,” and then you write about what it means for men to be allies of women. Could you talk about that?

M. Kaufman: We’re hearing that word “allyship” used a lot, particularly in the business community there’s a lot of male ally groups springing up. One of the things that we stress is that being an ally ultimately is not what you think, it’s what you do. It’s not a self proclamation of “look what a great guy I am,” or it’s certainly not “I’m here to save the day.” It’s how we act in solidarity, whether it’s men with women, whether it’s straight people with LGBTQ+ people, whether it’s white people with Black people, and so forth. So it’s what we do and how we act. And that allyship has to start with listening, which of course is a different entry, but it really starts with listening to the experience of others. Michael, over to you.

M. Kimmel: Well, I think certainly to be an ally is based on your action, but it requires a first step, which is: “I stand in solidarity with those who have been hurt by systems of inequality.” I could promote myself as the definition of privilege, you know, white, cisgender, heterosexual male. I have a nice long list of ways in which I’m privileged, and yet it hurts me morally. It hurts me in my heart to know that there are people who are hurt by those very things that benefit me. And so I then say that that privilege that I have is unearned, unfair, and I stand in solidarity with others. Now, then comes Michael’s argument of what are you going to do about it? And to be an ally means sometimes to step back and listen to what other people have to say without correcting them, without mansplaining it to them, although that’s probably another entry. But I think it’s about a posture and then an action.

M. Kaufman: We have to be really clear that this is not an act of collective guilt. It’s not collective shame. It’s not collective blame. It’s really an active collective love for the women in our lives. That’s what being a male ally is ultimately about.

AA: I’m so glad you brought that up because I really appreciated that one of the very first sentences in the book does address guilt because that’s been something that comes up over and over again. In my observation, one of the reasons that men can respond defensively is that they’re afraid of being accused of something that they didn’t personally do, or maybe they did do but they didn’t mean to do it. And that guilt is really hard for them to process. And this is something that my husband and I talk about a lot, but he is actually very empathic and will then start to just sink into this collective man guilt. And I wonder if you have any strategy for men like that who do care so much, but then they just get bogged down in that collective shame. What would you say to them?

M. Kaufman: One of the things I certainly say is that that collective guilt doesn’t help anyone. Yes, if there’s something we did and we are guilty of it then we should take responsibility for that, and responsibility for reparations or for change. But just that generalized guilt that I happen to have been born and have stayed self-defined as a man, that I’m not a certain skin color, I mean, these are these accidents of birth. And so to feel guilty about it doesn’t help anyone, it doesn’t promote change. In fact, it tends to paralyze people. And so I think that that’s one of the reasons why we really encourage groups of like-minded male allies to get together so we can embrace each other in this process of change and support it. One of the things you probably picked up a lot, you know, just hearing Michael and I going back and forth, is how much we love each other. And I think that that is partly what gives us strength to do our work and to do our writing. And it’s just that commitment to other men, you know, love your brother. And so I think that that idea of a brotherhood is really, really important to us to get beyond any sort of guilt. There’s a lot that we should feel angry about, that we should feel bad about, outraged about, but just that sort of generalized guilt, sure we feel it at times but it’s not helpful.

M. Kimmel: I just want to underscore exactly that. Amy, what’s your husband’s name?

AA: Erik.

M. Kimmel: Okay, so you’re talking with Erik, and as you just said to us, he’s very empathic and yet he’s become sort of weighed down by this guilt. It’s sort of like he’s just stepped in quicksand and he can’t get out, and it’s just going to make him feel worse. And that’s what Michael was just describing. That doesn’t do you any good. It doesn’t help you in any way achieve what you want to achieve in your life. You want him out there, you want him fighting for you, not just feeling bad about himself. So if guilt paralyzes us, then in fact, it’s almost a privilege to feel guilty. I can feel guilty because I don’t have to do anything. Some of us are not so lucky. Some of us actually have to do stuff whether we feel guilty or not. And so my feeling is that changing guilt, which is looking backward, what do you feel guilty for? Something that happened in the past. I would rather say, let’s take responsibility for changing it in the future. Now we’re not looking backward at all the bad things that were done in our name that we benefit from, but now we’re looking forward and we’re saying, it doesn’t have to be this way. One of the things that feminism is, if nothing else, is a movement of hope. It says it doesn’t have to be this way. We can make it better. So moving from guilt to responsibility is moving from looking to the past to looking to the future.

AA: Awesome. Thank you for that, that’s really helpful. A similar topic to me in that this is one that comes up a lot and is sometimes another side of this issue and kind of another facet of it is the fear of having to sit with anger. That’s one of the next A topics. And you explain why women are sometimes angry when they express their frustrations to men. And I know that it can be really hard for men to be the container that holds that anger, again, especially if they’re like, “I personally didn’t do this. Are you mad at me?” So what’s your advice to men when women seem angry about sexism?

M. Kaufman: I say this with tongue in cheek, but suck it up.

moving from guilt to responsibility is moving from looking to the past to looking to the future

AA: Haha!

M. Kaufman: I mean, be a man. Come on, you can take it. No, but seriously, when we hear anger, first of all, we just have to acknowledge that it comes from the reality of someone’s life. And it may be directed at us, that may be appropriate or it may be inappropriate. But when someone expresses their anger, it’s like we get to read this journal of their life.

M. Kimmel: I couldn’t agree more. Look, yes, women need to be very careful to say, “I’m not angry at you, I’m angry at the system,” etc. But look, what is anger? I mean, anger comes from real or perceived hurt. That’s a way we describe it. That’s a way we react to it. And in a system of dramatic inequality, which anybody could demonstrate empirically through any one of a number of measures, some people are hurt. Some people are hurting. So they can be angry about that and express it angrily. Sometimes people who are hurting, you know, I sometimes watch the reaction of people who pass by someone who’s asking for money, and it’s the people who pass by who get angry. Like, “how dare you intrude on me with your pain?” And my feeling about that is that pain is real. And anger is one of the ways, not the only way, but one of the ways we use it to try and express the pain that we feel, to somehow delegitimize it, to somehow say, “well, that anger is misplaced or it’s wrong.” It’s like telling someone their feelings are wrong. No therapist would tell you that. Feelings are feelings and everyone should have the opportunity to express them in ways that are constructive and move us forward. Sometimes it doesn’t happen. But as Michael says, we have to get used to it. People who are pushed down will be angry. And just because we say, “I stand with them,” it’s not a get-out-of-jail-free card. You still have to hear that they’re still angry about it.

AA: Well, that takes a lot of maturity and a lot of compassion, I guess, to be able to be willing to sit with that. I’m really inspired by that and grateful.

M. Kimmel: It is exactly those words. You can sit with it. You know, one of the things that I know I’m guilty of in my relationship is when my wife says to me that she’s feeling upset about something or angry about something and my first response, being a man, is “what can I do to fix it? I’m there. Tell me what to do and I’ll fix it.” And maybe sometimes what Michael was saying earlier is just sit with it. Just let me say it. Just let me express it to you. No, you don’t have to fix anything. Just sit with it and listen to me. That’s what I need now. Sometimes that’s what anger requires, not action but empathy.

AA: Yep. I know that’s been true for me, for sure. Those times, especially my husband’s really good at it, but just letting me talk it out and that active listening of repeating back and showing the care to just say, “Is this what you’re experiencing? I’m hearing you say this, is that right?” And just the care that he wants to understand me, actually, that’s all I need. So yeah, I absolutely agree. Anecdotally, that really helps me in my life. Okay, I’m going to skip a couple here and go on, is that okay?

M. Kimmel: Oh, we’re going past the A’s now?

AA: Yeah, we’ll be here for three hours if we dive in on every one! I wish we could, to be honest, but how about we go to ‘Beauty’? Does that sound okay? We’ll move to the B’s. I wrote a passage down here under the topic of beauty. I wonder if one of you could read it. Do either of you have the document up?

M. Kaufman: Sure. We write under Beauty: “The beauty question is complicated for straight men. We have to discover ways to allow ourselves to experience and express our attraction for women, while at the same time challenging ways that we might degrade, embarrass, discomfort, or harass the women around us. The goal is not to become a sexless creature who can’t delight in women and their bodies. It’s to discover ways not to do so at women’s expense.”

AA: Fantastic.

M. Kaufman: In other words, this is a sex-positive approach, you know, that it celebrates sexuality in all of its different forms, our attraction to others, but just to make sure that that doesn’t come out in ways that hurt others. It’s pretty simple.

M. Kimmel: Simple perhaps, but complicated as we also say. I mean, that’s one of the places where you get that defensiveness, I think, from men. Isn’t it? These men who say, “These women, they’re dressing so provocatively. What do they expect?” And for us to be able to say to each other, “This is a place where men have to talk to other men. Well, what do you expect?” I expect you to say the same thing that you say in a museum. “Wow, that’s a beautiful painting,” you say to yourself. But it doesn’t mean you’re going to grab it. It doesn’t mean you’re going to cut it out of its frame and take it home. It doesn’t mean you’re going to defile it. It means you’re going to appreciate it from a distance.

AA: Love that.

M. Kaufman: That’s a good one. I have to remember that one.

AA: Yeah, it’s fantastic. That’s so great. Well, I really appreciated that chapter because that’s something that I hear a ton. And I’m sure you know this, people talk about the changes that have happened especially since the #MeToo movement with men saying things like, “I don’t even know if I’m allowed to ask a woman on a date anymore. I don’t know if I can tell a woman she’s beautiful anymore.” And I actually have a lot of sympathy, to be honest. I think when things do change and good men are asking themselves, “What are the rules here?” and people who want to be good men and are nervous and they don’t want to hurt women. And when society changes, it’s hard for people.

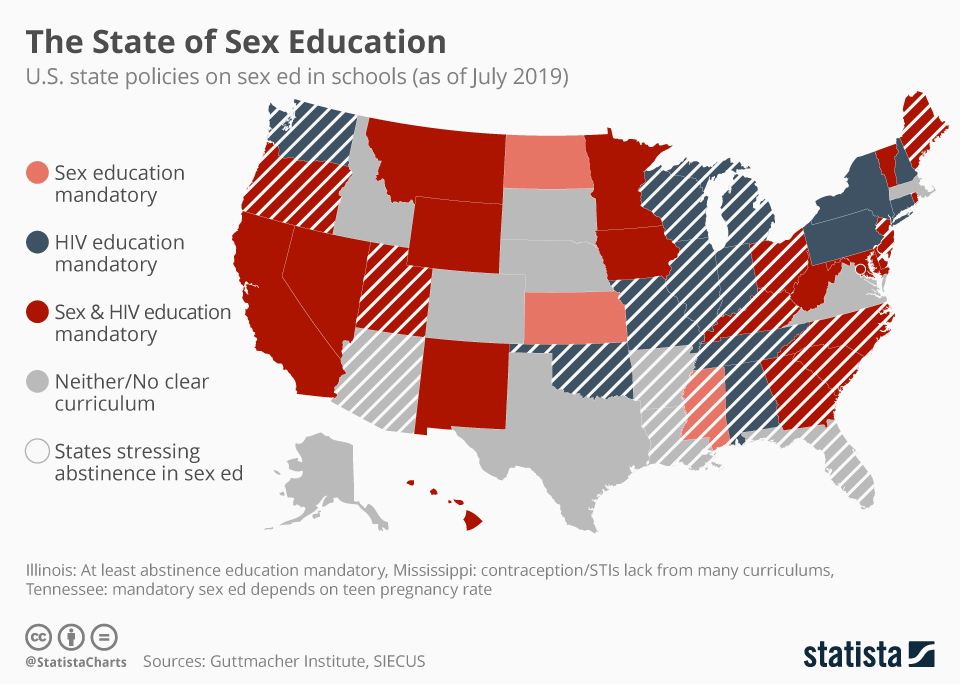

M. Kaufman: I do think we have to acknowledge that it is a difficult time. It’s a confusing time. And it is, you’re right, it’s absolutely great that men are asking these questions. It’s particularly important because sadly, for so many boys across America, their introduction to these questions is not a thoughtful, authentic conversation about relationships or desire, it’s really nasty pornography. You know, when there’s no sex education or if we have sex education that’s just our plumbing and diseases and doesn’t talk about pleasure, we’re basically seeding the territory to those who are creating violent forms of pornography to supposedly teach the young. And it’s terrible. This is why we need forms of education that include really healthy, robust sexuality education that talks about desire and pleasure, communication, connection, all those things in a very positive way. And I think some of those questions, the complicated ones, come up within that.

M. Kimmel: Let me also add something to that because here’s what I know about your son already. This is the thing that makes me so hopeful. Here’s some data. The Economist did this survey about five or six years ago in which they asked two cohorts of men in corporations a bunch of questions. And one cohort was 60 and older and the other was 35 and younger and the questions were something like, “Is it okay to call a woman ‘honey’ or ‘sweetheart’ or come up behind a woman and give her a massage in the workplace?” And of the 60 and over, 75 percent of them said, “Absolutely, perfectly okay.” And of the 35 and younger about 20 percent said “Okay” and 80 percent said, “Absolutely not, not at all.” So here’s what we know: A) Men are changing already. We know we have different rules now that we have to play by. I think if corporations were smart, they would figure out how to do reverse mentoring. Not have the older guys initiate the younger guys, but invite the younger guys to teach the older guys how to behave in today’s workplace. This is not your grandfather’s workplace, it’s not even your father’s workplace. The workplace today is completely different. And so when you say those things about how men feel, and this is so true, they feel they’re walking on eggshells. They feel that they don’t know what’s right to say anymore. Ask the young guys, they know.

AA: I love it. I love that. And again, that requires strength, that requires humility. And that might take some processing to think back, and like we were talking about with guilt, to think that is maybe something that I’m hearing that I have maybe committed some errors in the past. And that’s kind of hard to hear, but I think men are strong and they can do the work.

M. Kimmel: But this is the part where, I mean, I’m sorry to be so North American about this, but this is how you sell it. You sell this to corporations because think of the quality of the women that you are going to be able to attract if they have a workplace where men treat them as equals. Think of the quality of the men that you’ll be able to attract and retain. So this is a win-win. The changes that are already happening, that are inevitable, that are not going to stop no matter how many books they ban. The changes that are already happening in our workplaces, in our public arena, they’re not going to stop. So the companies that figure out how to do this right are the companies that are going to thrive.

AA: Hear, hear.

M. Kaufman: I would add that the countries that figure out how to do this are the ones that are going to thrive in the years ahead and the countries that are sadly rolling back women’s rights are the countries that are not going to thrive. They’re going to see more increased inequality, more increased pain and hurt sending people backwards. That is not the future.

AA: Right. And isolation from the rest of the world. Okay, let’s move on to a sad topic. We’re going to talk about domestic violence and wife assault. Michael Kaufman, I know this is an area of expertise for you. Could you talk about this a little bit?

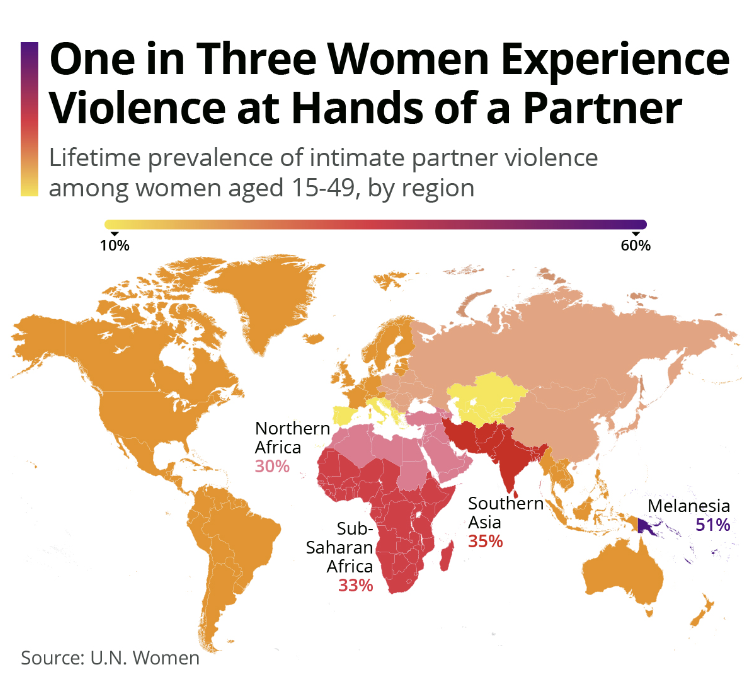

M. Kaufman: Yeah. We know that all over the world, depending on different studies, but really good studies, some studies will tell us as many as one in two, so 50 percent of women experience some form of violence at the hands of a man sometime in their life. It may be domestic violence, wife assault. It could be sexual harassment, it could be stalking, it could be sexual assault, murder. And so this is pandemic. It’s everywhere. It’s in all social classes and all societies. It is just a reality as women have told us over and over. It’s a reality of their lives. And it’s a reality that’s got to change soon and quickly. And so it’s so important that men learn to speak out. Often men don’t speak out. Most men don’t commit this violence. Even if one in two women or one in three women experience these forms of violence, it doesn’t mean that one in two men or one in three men commit those things because the same men will be multiple perpetrators of the violence. But we know that a significant minority of men do commit these acts of violence. But what we know, and this is what allows it to continue, is that the majority of men have been silent. And through our silence, we’ve allowed the violence to continue. And so part of our work has been to encourage men to end that silence. By speaking out against the rape joke that makes it seem normal to even talk about sexual violence, to speak out when a friend of ours or a family member makes a degrading comment about a girlfriend or his spouse, or verbally or physically puts down a woman. So just really encouraging men to speak out against this violence.

And to do so both interpersonally and to use the power that we have, that, as Michael said, men still disproportionately control the world. We still hold most elected positions, most senior positions in the corporate world and beyond, and in the world of religion, our religious institutions are still dominated by men. And so it’s so important that within these institutions, particularly if we have a position of institutional power, if we are the ministers, or the rabbis, or the imams, the priests, it’s so important that we use that sacred office to speak out against the violence and to say, “This is so incompatible with our ideas and ideals and beliefs. To the extent that it still exists in our communities, it must stop.” And to raise those voices and to do it out of love and compassion and passion and anger and commitment, whatever it is, but to speak strongly and to use our power and our voices as men to speak out.

AA: Thank you. Do you have anything, Michael Kimmel, on this?

M. Kimmel: No, that’s exactly right. As long as we pretend that it’s a problem of the violent guys, then we miss the point that it’s done because they assume and take for granted our silence about it. That is to say, our silence is seen as assent. It’s seen as justification. It’s seen as permission. When we withdraw that verbally, visibly, then they are acting alone. And then I think we have the possibility collectively to respond to it.

M. Kaufman: That’s so right. Most men have had the experience of hearing a joke, for example, or hearing a male friend or family member make a comment or do something and many men will feel very uncomfortable, but they won’t speak out. And part is that they think, “Well, it’s not my business.” Well, let me just say, it is your business if anyone around us is being abused or mistreated verbally or physically. But beyond that men worry about, “Well, how would the other guys see me? I want to be one of the guys,” you know, “I want to be in the club.” And so it’s this constant performance to fit into the expectations of manhood. And that’s where we just got to end it. And as soon as one of us speaks out, others will join us.

AA: Can I ask one quick and quite specific question? You wrote at the end of that chapter that some men might make the argument that “Women give as good as they get. There is as much violence from women against men as vice versa.” And that was on full display in the media right in the public’s reaction to the Johnny Depp and Amber Heard courtroom drama. And I wondered if you have a rebuttal or a response, and maybe not specifically commenting on that specific case, but when men say, you know, “She slapped him.” How do you respond to that?

M. Kimmel: Yes. So the data on this are pretty clear. If you were to ask people, as researchers have done, have you ever hit your partner or your spouse? An equal number of women and men will say yes. Ah, see? It’s just the same. Women hit men as much as men hit women. However, if you factor in the following things: How frequent was it? How serious was it? Did it involve any kinds of weapons? And most importantly, was the hitting in some way defensive? That is what we often find from women who hit their partners, is that they were defending their child from being hit. Or they pushed their husband away and he’s been hitting her, beating on her, she pushes him away, and it’s scored as one for him and one for her. So if you take into account severity, intensity, frequency, and the purpose of the violence, then it is extraordinarily skewed toward men as the perpetrators of the violence. And that’s why the research that suggests what we call gender symmetry is so deceptive. Because if you do count, ever in your life, an equal number of people will say yes.

M. Kaufman: And of course, there are cases of women being abusive in relationships. And we say the same thing that we say about men being abusive. We say it’s wrong. It’s got to stop. So, yes, it does happen, but the numbers are much less than the other way around.

AA: Thank you for that. Okay, we’re going to skip ahead in the alphabet and close out the conversation with the topic of religion. You also have a section on fundamentalism separately from religion, which I found really helpful. And as you both know, this is a relevant topic for me because some of the advances that secular society has made still haven’t been able to benefit the community of my faith tradition. So it’s hard to have a conversation with someone who really, truly believes that patriarchy is ordained by God. You know, who am I to question God? So anyway, this is all to say that I was really grateful that topic was in there because that’s very relevant to a lot of my listeners. Could you talk about that a little bit?

M. Kaufman: Both Michael and I feel very respectful of other people’s beliefs and the place that they play in our lives. But I think that respect, it’s not that the respect has a boundary, but I think that respect comes with an assumption. And that respect has to be mutual. And that within our religious traditions, these are traditions that human cultures created. And some would say God has imparted these to us, others would say our society has defined these traditions. But, from the dawn of humanity, we didn’t have all these different religions. These are things that emerged over the past 4,000 years. Particularly in the West we think strongly of the Judeo-Christian religions, which are called the great patriarchal religions. And they formed at a time that actually patriarchal societies were developing and codifying and strengthening. And they were all based on this idea of the role of the father. That’s what patriarchy means. And so our ideas of God were very much imbued with this notion of the father. We brought that into our religion. We brought it into our homes. We brought it into our armies and our developing state structures.

it is your business if anyone around us is being abused or mistreated verbally or physically

And I think that for many people, they bring us immense meaning and joy and connection with others, and an explanation for the mysteries of life. But I would just say that ultimately culture should serve people, people should not just serve culture. Both Michael and I were raised in the Jewish traditions, but I don’t think either of us would say, “Well, I have to do this because my religion has taught me I have to do it.” Because we have to question. We have to question the things that are in loving and wonderful parts of our religious traditions. We have to celebrate the wonderful parts and we have to say, well, other parts have not been so wonderful. Other parts have been very hurtful to particular groups. And I think partly it’s healthy, it’s exciting, and it’s part of what keeps religions alive, is actually to bring that questioning into the religious institutions.

M. Kimmel: I think that’s a great segue to what I want to say, because I was raised Jewish, as Michael said. And one of the things, I mean, in the Old Testament God smites a lot of people, right? He is vengeful and angry, but only because of what people do, not because of who they are. When they do something against him, he smites them. It’s fiery, it’s lightning and thunder, but not because of who they are. And I think it’s really important. God, in the Old and New Testament, never says anything. God doesn’t say anything because God didn’t write it. God never says anything about treating people badly because of who they are. In the beginning, male and female, he created them. Them, plural. Male and female. Created them. We are all children of God, full stop. So where we get the justification to treat some people badly, to make rules, those are the rules of men, not of God. Those are the rules that men, as Michael said earlier, consolidated power when they felt super vulnerable from attack, from mysterious circumstances, circumstances that they couldn’t figure out. But it’s not the only way to think about these issues. I think that religion can be the source of amazing solace, community, emotion, and meaning. But I also think it can be used as justification for the exact opposite of those. So I look to religion, like in the Black Church, for solace and community and understanding that there’s a better world to come. But I also feel that it can be used to justify inequalities that were never, ever intended.

M. Kaufman: That’s so well put, Michael. And sadly, right now, it’s also being politically weaponized in some incredibly scary ways.

M. Kimmel: If you’re truly religious, I think the only bright posture, the people that we have adored, the people that we have idolized, that we have felt are the messiahs, they have been the most humble people in the face of the awesome power of God. The only appropriate response is humility. Anybody who sanctimoniously tells me what I should be doing, how to interpret the word of God, and is not humble about it, I feel like they’re missing the point.

AA: Excellent. Hear, hear. Well, Dr. Michael Kimmel and Dr. Michael Kaufman, I can’t thank you enough. I’m so grateful for the work that you do in the world. I highly, highly recommend the book to listeners. Again, it’s The Guys’ Guide to Feminism. Am I missing part of the title?

M. Kaufman: Nope.

AA: Nope, that’s it. I love it. It’s short and sweet. I love it. The Guys’ Guide to Feminism. Go out and buy a copy, buy multiple copies and give it to the men in your life. And again, thank you so much for joining me in this conversation today. I learned so much from you both. Thank you.

M. Kaufman: Amy, Thanks so much. This is really fun. And thank you for your work.

M. Kimmel: Thank you.

being an ally is not what you think,

it’s what you do.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!