“Interspersed within this colossal fortress of patriarchy in Africa is the injection of equal, but opposite resistance by women”

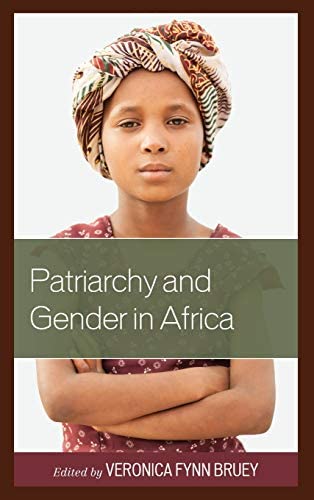

Amy is joined by academic and advocate Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey to discuss her book, Patriarchy and Gender in Africa, and discuss the impacts of patriarchy on the African continent.

Our Guest

Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey

Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey is a multi-award winner and a passionate academic and advocate. Holding six academic degrees from four continents, she has researched, taught, consulted, and presented at conferences in over thirty countries. She’s authored five books, several book chapters, and journal articles. She’s the founder and editor in chief of the Journal of Internal Displacement, the co-lead of Law & Society’s collaborative research network, she is the lead of Law & Society Association’s international research collaborative, Disrupting Patriarchy and Masculinity in Africa, the founder of The Voice of West African Refugees in Ghana at the Buduburam refugee settlement in Ghana. She is also the Australian National University International Alumna of the Year in 2021, and the president of the International Association for the Study of Forced Migration, and a co-chair of Africa Interest Group American Society Of International Law. Currently she is an Action Canada Fellow, from 2022 to 2023, and the director of The Flower School of Global Health Sciences and an assistant professor of legal studies at Athabasca University. Veronica is a born and bred indigenous Liberian War survivor.

The Discussion

Amy McPhie Allebest: Welcome, Veronica.

Veronica Fynn Bruey: Thank you, Amy, for having me! I am very honored and appreciative of this very special invitation to be a part of your amazing podcast. So, thank you.

AA: Thank you for being here, I’m so excited! I was just thrilled when I found the book and I read the book and then contacted you. And it’s been such a joy to get to know you, and I’m really excited to have this conversation today. I’d like to start by reading your formal biography and then in a minute I’ll ask you to introduce yourself more personally. But first we’ll just start with your professional bio: Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey is a multi-award winner and a passionate academic and advocate. Holding six academic degrees from four continents, she has researched, taught, consulted, and presented at conferences in over thirty countries. She’s authored five books, several book chapters, and journal articles. She’s the founder and editor in chief of the Journal of Internal Displacement, the co-lead of Law & Society’s collaborative research network, she is the lead of Law & Society Association’s international research collaborative, Disrupting Patriarchy and Masculinity in Africa, the founder of The Voice of West African Refugees in Ghana at the Buduburam refugee settlement in Ghana. She is also the Australian National University International Alumna of the Year in 2021, and the president of the International Association for the Study of Forced Migration, and a co-chair of Africa Interest Group American Society Of International Law. Currently she is an Action Canada Fellow, from 2022 to 2023, and the director of The Flower School of Global Health Sciences and an assistant professor of legal studies at Athabasca University. Veronica is a born and bred indigenous Liberian War survivor. So I mean, we can tell, listeners, from just that biography how lucky and honored we are to have Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey with us here today. And that’s your official biography, Veronica, but I wonder if you could share a bit more of your personal story as well.

VB: Yeah, thank you, Amy. I really like to introduce myself personally whenever I’m given the opportunity because for me, that’s the real me and that’s what has actually propelled me to get to where I’m at at this moment in my life. So, I want to say thank you once again for the opportunity to share part of my personal experience. And in honoring the title of the podcast, please permit me to dwell on aspects of my personal experience that actually relate to breaking patriarchy. So I grew up with a– I call her a feisty disciplinarian single mother. My mom had eight children and she was left to raise us on her own. We grew up very poor in Liberia, in the capital city which is Monrovia, and instances of where I remember stark poverty were living in a mud house and living in a house without a floor. My mom didn’t have money to cast cement on the floor so we had to live on a dirt floor and had parasites and insects boring into our skin for years because of living on a dirt floor and not having shoes to wear on a dirt floor. Another instance of growing up on Duport Road in Paynesville, Monrovia, Liberia is not having a bed to sleep on. So, my mom couldn’t afford a proper bed and a mattress– she had gone to borrow, or not borrow but ask someone to give a used bunk bed frame. And my sisters and I slept on a bunk bed frame with a wooden cover. And the wooden cover actually came from an armoire that had a curvy door, you know it looks like this really expensive armoire… Because I remember it, it was covering up the wooden side of the door of this armoire. But it wasn’t square, it was in the shape of a beautiful woman or something. So we put that on the bed and we covered it with cloth. No mattress to sleep on. So at this curvy end there was a hole in the mattress, so when we slept bad, our feet would just go and sink. [laughing]

AA: Ah, oh my goodness.

VB: You know, I love to tell these stories not in a negative way, because people think what you have acquired, whatever it is society expects you to have acquired, they think it just comes so easily and people tend to forget that part of their lives that honestly brought them to where they are. Because without those experiences, I’m not sure I would be here. And it was a tough experience, and because a lot of people were poor around us, we didn’t necessarily see it as poor. So, growing up was really harsh and you know my mom has so many experiences, but I won’t go into… Like I said, I want to highlight some of the aspects of my life that just show my mom as a woman, her bravery, her strength, and her ability to raise her eight children. She built a house on her own, it was her land, and we all built that house together. It was a mud house infested with termites and no floor, but we built it. And then between 1979 to 1986/87, I was in elementary school at the time, my mom just struggled. She struggled so much, even though she was a civil servant, that she had to ask me as her first girl to help bring income into the house. So my mom would wake us up at 2:00am and we would make pastries. And I would take these pastries to school, so while my friends are playing I’m the one who is selling the pastries during recess or during break. And we were not allowed to sell in school, of course teachers didn’t like that because they felt it was an abuse, but the reality is how do you expect to put food on the table so I can come back to school tomorrow if I don’t help my mom get some income? So I would hide and I would sell during break and I would come back home with good money that my mom could use to buy us food. And during the weekends, especially on Saturday and Sunday – my mom is quite religious, she’s quite Christian so we didn’t do any of that kind of selling or working on Sunday, we went to church– but on Saturdays she would send me out into the town. You know, put the bread box on my head or the meat pie on my head and I’d go around and sell just so that we could get our extra cash for us to be able to find food.

I’ll fast forward to the war in Liberia. It started in 1989. So, as if we hadn’t gone through enough poverty, and difficult life experiences acquiring education, walking for miles to go to school every day, as tiny as we were waking up at two in the morning for the dough to rise and then 4:00 am bake it and get ready for school… It was just crazy. Then the war started in 1989 which also sent us into a completely different direction. We were internally displaced in the country for about three years, from 1989 to 1992. And then we left, and I’m not going to go into details, but it’s just the reality of my mom putting on her best self in the midst of deadly conflict, war, violence, all kinds of violence including rape against little girls, to make sure she protected me and my siblings. But then my mom got sick during the war, and she was really sick that she didn’t have much strength to do the things that she would normally do for us. And so that made it really, really challenging for me as the first girl because then I had to grow up really quickly. I had to take my mom’s place to look after my younger siblings, who at that time were between the ages of three years old and nineteen years. So we were pretty young! [laughing] And looking after my mother and making sure that she didn’t die, because she did have a deadly disease that could have killed her anytime during a war, but I’m happy to announce that my mom is not dead, she’s still alive! And then making our way on the deck of the Ghanaian peacekeeping vessel to go to Ghana as refugees. So we left in 1992 and then lived in Ghana for about one and a half years. And life became so difficult for my mom in Ghana, my mom decided that she was going to go back to Liberia because she’d rather die in Liberia than to have an unnamed grave in Ghana. That’s how proud she was of her country. She would rather go back to Liberia and die where there will be a gravestone or tombstone than to die in Ghana where most people were just being put in a hole at the time of the war. There were just too many bodies to have individual graves. So my mom left and went back with my siblings, but I stayed in Ghana. And I remember at a young age telling my mom, “you always told us that education was most important, you always value your education, so Mama, why is it that you are going back to Liberia when we have the opportunity to go to school here?” But after the fact, as an adult, I now play back those experiences and realize that my mom was in the worst phase of her life. I think she was probably in early menopause. And it was just a difficult time for her. I still have very painful memories of my mom’s suffering and just feeling so worried and stressed. She had lost so much weight, she couldn’t provide for us, we had no food– I mean life was hard in Ghana, to say the least. So my mom went back, I stayed in Ghana, and that exposed me to a lot of vulnerabilities. Yes, we grew up poor, we didn’t have anything, but Mama being around as our protector, as our guardian, as our as our parent and our everything, leaving was an opportunity for me to be vulnerable. So I became vulnerable to a lot of abuse after Mama left and went back to Ghana. I ended up staying– Yes?

AA: Well, I was just going to say – I didn’t want to interrupt you – but how old were you when your mom left and you were on your own in Ghana?

VB: I was about fourteen, fifteen years old.

AA: So who did you live with?

…my mom decided that she was going to go back to Liberia because she’d rather die in Liberia than to have an unnamed grave in Ghana.

VB: I went to the church, I lived with someone who was in a church because I had to go to the same church my mom was in. I had to go to the church to ask for assistance. I already gotten some assistance from the church, so the head of the welfare department in the church at the time, Mr. Millican, was the one who literally took care of me for those years that I was in Ghana. But it happened afterwards. Mama left at a really difficult time. It was hard for her to make that decision to go back, and so when she decided to leave and I said I really wanted to listen to what she had said that we should value education because it was going to change the intergenerational poverty in our lives, I wanted to stay. I’ve always loved school as a little child and I’ve always done well in school. So I think my mom knew that. She was worried I was staying by myself with no family. But I think she had hope; I think my mom had given me what it takes or what it took to survive in life at that young age. So, deep down in my mom’s heart I think she knew I would be okay. But it was the worst pain because she’d never been separated from any of her children like that. And suffice to say her first girl– like, my mom did everything she could so that my life would be far better than hers. I won’t become teenage pregnant, I will go to university, and all that happened for me. But at the cost of being both physically and sexually abused and not seeing her for thirteen years, she and my siblings, being on my own… Yes! So, talking about women power, right? [laughing]

AA: I just– oh, the heartbreak! I’m just imagining for you and for her… oh my gosh, Veronica I can’t even imagine.

VB: Thirteen years not to see her. Yeah, so that was what happened in Ghana, but at the same time it was the life changing moment. 180 degrees. Literally, Mama left; I became vulnerable. I had a lot of challenges in Ghana, living there for the rest of the eight and a half years after she left. But I had the opportunity to finish my secondary school, I had the opportunity to finish my first university degree, and then I had the opportunity to leave and come to Canada. And because of that sacrifice I became the only person to have this amount of educational exposure in my family. If I had gone back, I would have definitely ended up like my sisters and my brothers who didn’t have any school to go to because there was the war, who then were kind of coerced into getting married and having children at a much younger age compared to me, who had a child when I was literally 39! Like, come on… [laughing]

So, when I was in Ghana and just about to finish my first degree from the University of Ghana, I had an opportunity whereby a friend came to me and told me about this World University Service of Canada Refugee Sponsorship Program. And I refused to apply for the program because I was angry that they didn’t value education from the global south, that I would come to Canada and have to repeat my studies and do another bachelor’s. And my friend Lawrence believed in me more than I believed in myself, and he applied for me, literally, and I got the program and I came to Canada and I actually did a second bachelor’s degree. [laughing]

AA: Oh my goodness! Because they really didn’t recognize your bachelor’s because–

VB: Because it was from Ghana!

AA: No way. Oh my goodness. So you started over!

VB: So I was able to transfer all my credits from University of Ghana and it took that into the first and second years, and so I did two more years and I got a second bachelor’s in psychology.

AA: Amazing.

VB: Yeah, and the rest is history. Since I came to Canada it’s been a great experience of adding five additional university degrees. And you know, milestones for me are getting married and having a child at a very late stage in my life because I just really wanted to spend time enjoying my education and I did not want to have 8 children. I didn’t want to be weighed down like my mother was, the sacrifice she made, and now that I have a child of my own I really appreciate how much sacrifice she actually made to give us the life that we have today, you know? So, I listened to her. Whatever she said, I listened to her. And it was a lot of violence that I experienced along the way in trying to tread that course and create that path for myself, a brand new path that has never been traveled in my family before. But it has brought me to a point where, you know, I feel very opportune and I feel very grateful that my mom was able to lay down those sacrifices and those disciplines and those encouragement and support regardless of the fact I was separated from her since I was literally 13, 14 years old, technically. Coming to Canada and acquiring all this education has opened a brand new door of opportunities for me, but honestly it has also predisposed me to a new form of discrimination and racism that I live every day. But I don’t want to sound sad and discouraging. You know, there are two parts of this journey that I want to highlight before I close on this session. One is marrying a husband who has respect for equal partnership in a relationship. He honestly blew my mind when we had our son and he said he would resign his job and stay home to look after our child. So we reversed roles, where he became the stay-at-home dad and I was the breadwinner for the family. And that was honestly a remarkable experience because that’s not what I saw in my mother’s life. She was everything: she was both mother and father all through my life. So to have a stable relationship in my life now is unexpected, and to have one where my husband can stay at home and look after our child was remarkable for me.

Another part of the experience that I want to highlight in light of this podcast, Breaking Down Patriarchy, is the fact that I respect motherhood a lot. The best part for me being a mother was breastfeeding. I mean, I’m still a mother, but when my child was really young breastfeeding was my most memorable experience, and being able to breastfeed my child from birth to when he was three and a half years old for me was making a statement to the world about women’s place, women’s role and the role of children in our so-called society we have created, where children are back home and mothers are back home looking after them. So our son, before he was eighteen months old, we had traveled to five continents and ten countries around the world, literally breastfeeding him. He’s been to conferences, workshops, he’s been to meetings with Vice Presidents, with University Presidents, faculty meetings and airports, on the streets, running, playing… I just breastfed him anywhere and anytime and I did not care what people thought about my nipple. I’m just like, I’m sorry but my breast wasn’t created as a sexual symbol, it was created to feed a child. And I didn’t care. So it was an empowering moment for me and experience, and just walking down the podium with my young eighteen-month-old son in my hand to receive my PhD was a statement to the world that women do not acquire these things on their own. They acquire it with their children and looking after men, and men all the time, I mean we care for men. We love men. We look after our sons, we look after our boys, we look after our colleagues. So, it was an inspiring moment for me.

AA: I’m so grateful that you shared all of that and I will say too, when I was looking you up, when I had ordered your book and was going to read it, and I was just looking into your work, and there is the most beautiful photograph of you receiving your PhD with your little son on your lap. And I think it’s the moment where they’re putting the doctoral hood over your head, is that right?

VB: Yes.

AA: Oh my goodness. In fact, I think we’ll put that picture on the website so listeners can see it because it brought me to tears. It really did. I showed my whole family, I was like “get over here and look at this!” This is just the most powerful visual image of this woman as a scholar, as a professional, and as a mother, and those things being integrated in your life. So I saw that too, but now knowing the backstory and how that was very intentional, that’s really powerful.

VB: Yeah, I cried throughout. [laughing]

AA: Yeah, amazing. Well, congratulations on all of your work, and thank you again for sharing that story. So powerful, thank you. And as you shared your personal story, it struck me that patriarchy was a very strong force that was causing a lot of the struggles that you had to endure. Like, that dominator culture of the men who caused the Liberian Civil War that displaced your family, and the sexism that propels men to use sexual abuse as a weapon of war, and enables abuse in so many scenarios. So, now I’m wondering if you can talk about some more examples of how you see patriarchy manifest in everyday life.

VB: Generally, patriarchy and gender walk hand-in-hand on the continent. And it is seen every day in the way we’ve structured our society, in the blank stares you get when you sit on a bus and you go for the front seat, and it’s like, women don’t sit in the front seat, it’s men. I mean, local buses in Ghana, for instance, it’s men because it’s a tough place if the driver is driving too fast, and if anything happens we don’t want a woman to be the first one to die. So don’t sit in the front seat.

AA: Ohh, so it’s more paternal, it’s kind of patronizing and protective, but it’s not misogyny. It’s protectiveness, I see. It still doesn’t feel good, but it’s more benevolent.

VB: Yeah, sometimes it feels protective and honoring women and patronizing but still– Let me decide if I want to die! [laughing] You should do that for me! You know, in Ghana we have the same experience, like we have similar experience with cars and public transportation. Women don’t sit at the door. Women are always squashed in the middle. In Liberia, you can’t put a man in the middle because he’s going to protect you if anything happens. So not only can she not sit in a front seat in the buses in Ghana, she can’t sit at the end of the seat in the back seat, she has to be confined to the middle! [laughing]

AA: Wow, that’s so interesting! And I’m sure there’s no rule, but it’s just a cultural norm, you’re saying?

VB: Yeah, yeah, and it’s expected. That’s the norm and women know– Of course, when you come from a different culture or society or country, you don’t notice that. And when a white person, a person of a distinctly different culture from your culture appears, the norm seems to disappear. People understand that oh yeah, she’s not from here so it’s okay for her to sit at the door. But you from the culture, usually if you’re Black, they make assumptions, right? Because you’re from Liberia or you’re from Nigeria, you’re not necessarily Ghanaian but they make assumptions, because we are all Black so she must be from here and she must know the rule. Why are you sitting here? Go to the back! [laughing]

AA: Interesting. Wow.

VB: Yeah and so those experiences every day of our lives– I mean, you go to the market, the same story, you hardly see the boys or the men in the market selling. If you do, they are the cobblers doing shoes or they’re carrying really heavy clothes or stuff in a wheelbarrow. But fish, I mean, you almost never see a man selling fresh fish in a market! I mean, sometimes meat yes, because they are the ones who kill the cows and mostly the Northerners would do that, most times. Because, honestly it’s seen as an honorable thing to do, to sell meat back on the continent. But usually women are the ones spread throughout the market. Women are the ones walking if it comes to the forum, they’re the ones – I’m sure you’ve seen the image – the baby on the back and the load on the head, and they’re holding another baby on the side, and maybe an ax or a cutlass or something for the field. It’s just typical. And the men are usually walking in the back with nothing or maybe one cutlass. That’s the picture, and it’s real. So, yes, it’s very profound. And then when you come to our colonial set of governance, where we’ve copied from the Western society about the structures in the forms of government, you barely see women. You know, recently I read a story about a Kenyan MP who took her baby because she didn’t have a babysitter that day, took her baby to work, and she was literally commanded to leave Parliament because it wasn’t a place for babies. And I’m like, who raised all you men to sit here and do the things that you’re doing? A woman did it. You think she did it in a corner somewhere and that she shouldn’t be allowed to come to this space, especially when she has no one to look after her child? Yeah, so part of the reason why I constantly was making a statement with my son. I took him everywhere. And dare you tell me to leave a meeting or cover my breasts? I’ve had those experiences in a taxi or on the street or at the airport. Oh, can you cover up? No, you turn your face somewhere else, because I’m not covering up.

AA: Wow! That’s amazing. Now it’s sinking into another level, because you did have a supportive husband who certainly would have– I’m guessing that you didn’t have to take your baby to all of those meetings. That’s what I’m hearing you say, is your husband would have been perfectly willing to take the baby, but you did it out of principle and to try to change the culture and bring awareness.

VB: Absolutely.

AA: Wow, that’s amazing. Yeah that didn’t quite even click when you said that at first, that it wasn’t even a necessity for you to take the baby…

VB: No.

AA: But it was activism.

VB: It was activism. It was a big statement I was making.

AA: Yeah. Well, I think a perfect way also to introduce the concept of patriarchy and gender in Africa, since that’s the title of your book, is if you could talk about your book a little bit. Why you wrote it and maybe what the main thesis is of the book.

VB: Thank you, I really appreciate that. You know, it’s very interesting that that’s the first book on patriarchy and gender in Africa when, I mean it’s part and parcel of our lives as both male and female, or whatever other gender we identify as, we have some element of patriarchy and gender. So without taking too much more time, I’d just really like to read an excerpt from the book that would give a good picture of what this interesting book is about. You know, from my lived experience and from other Africans– so it’s an edited book that has about 12 to 15 authors (because some chapters are authored by more than one person) and delve into different aspects and issues of patriarchy and gender around the continent. But I’m going to read this excerpt from the introduction of the book. So it goes, “The primacy of patriarchy and discrimination against women in Africa requires a comprehensive and holistic approach that meticulously examines why girls and women struggle to rise above entrenched misogyny, and how they can flip their socioeconomic status and leadership role in the society. The book Patriarchy and Gender in Africa is long overdue considering the autocratic and violent regime of governance of men in the public and private sectors within and across nations of Africa for centuries. Even in the modern colonial and post-colonial eras, both white men and Black men have controlled the masses in Africa without including women in leadership. It is no secret that men hold dominant leadership roles at a disproportionate rate, or that they insert power and wield control over women in diverse forms of social systems and institutions globally. Patriarchy, or androcentrism, the supremacy of fatherhood whereby women, children and other men rely totally on the rule of the father, is entrenched in many societies, cultures, systems and institutions around the world. There are few significant exceptions to this dynamic, and they are not seen in Africa. In every facet of the continent, male dominance is fierce, violent, aggressive, and unrelenting. Interspersed within this colossal fortress of patriarchy in Africa is the injection of equal, but opposite resistance by women.”

AA: Thank you, that was the perfect introduction to the African continent and to your book, which I really recommend to listeners. Again, it’s called Patriarchy and Gender in Africa, and you can easily find it online and buy it. It had such an interesting range of essays. It’s an anthology, and one that comes to mind is women not being able to go to soccer stadiums. Oh my gosh! That’s something I’ve never thought about in my life. But it’s just this academic research on this topic and this very relatable situation on something, again, that I had never heard.

And another chapter that I thought was so fascinating and so important was a chapter by, the author’s name is Verena Tandrayen-Ragoobur. And she’s from Madagascar, and she wrote a chapter called “Building the Patriarchy Index for Sub-Saharan Africa: Perceptions and Acceptance of Violence Matter Most.” And there were some really interesting and informative charts and tables that reflected her research on current gender relationships all over the continent, I think including all of the countries on the continent from Angola to Zimbabwe alphabetically. And I wanted to quote a little bit from that chapter, if that’s okay, Veronica, because I thought it was such an interesting overview. It’s particularly– this part is on the topic of violence, but she says, “Two indicators were selected to analyze the extent of patriarchy within countries and the difference in the levels of patriarchy across nations. The two indicators refer mainly to gender roles and stereotypes, and to perceptions and acceptance of wife-beating. Gender roles or stereotypes are measured by decisions in the household regarding healthcare of women, household purchases, and visits to the woman’s family. If the husband or partner is the only one who makes these decisions, then he exerts some form of control or power over the household and over the wife.” So she has done this research on who makes the decisions in the household, right? And so she looks at heterosexual couples all over these different countries, and she says, “Countries such as Burkina Faso, Cameroon, The Democratic Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, and Senegal provided data showing that more than 50% of women reported that their husbands make all those decisions. Men were also asked about the decision-making in their household across all the household matters. When men reported their participation in the decision-making process, the figure across the countries was much higher, ranging from 61% roughly to 94% of men reporting that they made all the decisions in the household.” But she then says that a much lower percentage of women said that their husbands made all the decisions. And I thought that was so interesting because it shows men self-reporting, 94% of men saying “I make all the decisions,” shows that they want to be perceived as being in charge, right? So that seems to be what is prized among men in those particular cultures, is that right, Veronica? Am I reading that correctly?

It is no secret that men hold dominant leadership roles at a disproportionate rate…

VB: Yes, absolutely. And this chapter is very fascinating, and the fact that she’s been able to do that data statistics, as you pointed out, across the continent…These are data that are really hard to come by, and honestly most times you have to get self-reporting to be able to get that kind of information because it’s not something people will report in a study or report within government data. The government doesn’t look for that kind of statistics or that kind of information. But yes, Verena is actually correct. In our so-called unequal society, men pride themselves on being able to have absolute control over their house. And I think that expectation honestly kills men, in my view. It overburdens men. And I can give you a good example whereby students went to a law school in Ghana. And parents, through sweat and blood struggle, sell, make all the sacrifices for their daughters to go to law school. And it will interest you to know that after their legal education in Ghana, most women tend to go back to the house. To birth and to look after children rather than practicing, because the country is entrenchedly gendered. Women have certain roles, and women can make decisions about where to work, and the choices about employment, and owning a law firm– You kidding me, I mean that’s not a woman’s place. Courthouses are filled with mostly men and few women, and in the instances where women lawyers are given opportunity to lead, they’re always silenced and told to go back to the back row and not be in the front. So yes, and that pressure to be a single-income person is overwhelming. And when you’re going to get married in Ghana– unlike Liberia, which has copied Western marriage practices and traditions – in Ghana the young man has to be able to buy a big bride price, so to speak. And that pressure scares young men. They are not able to make decisions for marriage for love because they are expected to pay so much money and buy so much stuff for the bride-to-be. And if he’s not able to do it, sometimes he’s made a shame among his peers, and he’s told “you will continue to live in your mother’s house and you can’t even take care of a woman.” You know, it’s an embarrassing and denigrating experience for young men and I think it puts too much pressure on men and too much expectation that they have to have this absolute control over everything in the house. So mothers would sit and wait for fathers to come home before decisions are made, sometimes to a deadly cause. It’s problematic. So just think about flipping the coin and thinking about men’s health and where it’s important to not just see them as patriarchs, but also see them as human beings who need relief from this strain and the stress that society puts them under.

AA: Are there any other key points of the book that you’d like to share, Veronica? There were so many amazing chapters and important parts. But if you had a couple that you’d like to share with listeners.

VB: I really like Manase’s chapter as well! I mean, I don’t want to sound favorable to some and not talk about some but yeah, his chapter on Zimbabwe and soccer is what– I still work with him because of how fascinating I find his work. There’s a whole different ball game going on at the ball stadium when it comes to cheering for football teams and how gender is relatable in that sense. You know, women can say certain things, women can sing certain songs, and it’s only when they’re at the pitch and gathered together in that – you know is the whole mob mentality kind of thing– but once people are dispersed into their homes, and they will hear some of the songs that Manase was talking about in his chapter. It’s actually horrible! I mean, talking about women’s private parts in those songs. It’s disgusting. But I had the same experience at the University Of Ghana and that’s why I could relate to him, you know. Whenever the boys or the male students from the male hall were together doing their thing, they did it as a group and they didn’t really care that they have mothers, they have sisters. But when you meet them one-on-one, I mean, they’re so passionate! They’re just really understanding and feel terrible that such a thing would be said about a woman or their sister or the mother. So yeah.

AA: Just raising awareness then, and saying, are you realizing the words that you’re singing right now? Yeah. Well I’d love it if we could talk more about your home country of Liberia, Veronica. And see if you could tell us some important features of gender relations in Liberia.

VB: Yeah, thank you for the question. I’m quite a passionate Liberian, I love my country, I love where I was born. But at the same time, there’s so many things about this country that I am personally not proud of and struggle with. First is just the immense poverty in the country for over 175 years. It boggles my mind every day. Liberia’s Africa’s oldest republic– why is it that we are so poor? And disproportionately women are more poor than men because we are a patriarchal society that favors men and boys. And so then boys and men get more opportunities and women continuously struggle through their lives. Not that boys and men– some of them don’t struggle but this is in comparison to girls and women who just struggle so much more to acquire anything. So for me, the stark point is: why is this country so old and why is it struggling with poverty and specifically poverty against the girl child? I strongly feel the worst curse anybody can get in life, and I know this is strong and profound to say but that’s my lived experience, is being born an African girl. I feel it’s a curse and I feel it’s the worst experience any young person can have in their life. Just because of all the challenges and the difficulties that a young girl child born in Liberia will have to go through, and maybe lucky if she lives to be fifty years old. This story is honestly grim, honestly grim, honestly sad in Liberia when I think of gender relations. Just basically the amount of poverty that girls experience, which make them vulnerable to all the other things: rape and domestic violence, intimate partner abuse. But women are the largest agricultural producers in Liberia and most of Africa, actually.

AA: Wow.

VB: Yes, because most women do the farming and they feed the continent. They feed Liberia. So that’s something to give a smile for. And despite Liberian women’s challenges, I find Liberian women to be quite feisty and resistant. They fight back. They’re constantly fighting back. Yes, society wants to box them in and put them in a hole, but Liberian women– I mean, just watching my mother fight back constantly and reclaim, and reclaim, and reclaim, her place and her role as both a male and a female raising her children is phenomenal. And also to highlight and just respect those many females, some of whom are well known and I and many other young Liberians stand on their shoulders to continue to thrive today. You know, Liberia is Africa’s oldest republic, as I said, we’ve had a total of twenty-five presidents since 1847 but we’ve had one female president who was the first female president on the continent! Elected democratically, so that’s something we are all proud of.

AA: So, how would you describe some of the features of gender and patriarchy in Liberia today?

VB: Rape is so rampant and common in Liberia. Of course, my PhD work is focused on systemic violence in a broad range of structural violence, cultural violence, institutional violence, and of course interpersonal violence where rape comes into play. But it is a complex web of the structure, the culture, the society, institution, all playing a role in sustaining and maintaining this kind of patriarchal violence in the particular form of rape. It is so common, and I think what broke my heart mostly during my research work in Liberia, was hearing experiences of young babies and children less than ten years old. Why it is so common in Liberia blows my mind. I struggled with it for the year that I spent in Liberia collecting data. And of course for those years I was also vulnerable to all kinds of violence.

…why is this country so old and why is it struggling with poverty and specifically poverty against the girl child?

Tying into rape is the experience of sex for grades. I’m baffled every day why asking our neighbor when I was about eleven years old to help me pay my school fees or buy my textbook, was invited into his bedroom. And if it wasn’t by some miraculous intervention that I have no idea what it was, he would have raped me at that young age. I just remember saying “okay, I have to go now, I think my mom is looking for me.” And that was it. Why do girls always have to be told by male teachers “before I can help you in your lesson or do anything better for you, I have to sleep with you for you to do well in your school.” I’m just always amazed. I know we always say as feminists “rape is about power and it’s about control.” I feel a great sense of power and control when I pay a young man’s school fees or I am a mentor to him and help him, guide him, and direct him in giving some leadership skills. I feel so empowered as a woman doing it for a young man. I don’t know why I would want that power to be sexual. I don’t know, I just struggle. Maybe because I’m not a man and I can never think as a man, so I have no place to have that empathy. But I just struggle with it, that I would never in my wildest dream or in any situation wish in the back of my mind or even maybe have a thought about oh, you need your tuition to be paid? Let’s go, come to my bedroom. Yeah, so anyways, because women and girls are so poor in Liberia and not given the opportunity to go to school. And you will see the trajectory; girls and boys will start in kindergarten, elementary school at the same percentage, but by the time girls start to get to puberty and start to form their breasts, they gradually drop out of school. By twelfth grade you have maybe ten or fifteen girls in a class of fifty or seventy students. And it’s so heartbreaking, and it’s that experience of transactional sex that brings women to that very low level of poverty. So they’re in school alright, and start to form, you know through puberty, and start to form their body or their shape, and then men would start to ask them “oh, come to my house and bring me some water.” Especially in rural communities. Not necessarily in the city – it happens in the cities a lot – but I’m speaking mostly to rural and isolated communities. “Come and wash my clothes, come and clean my house. Okay, you said today you don’t have money to cook. You don’t have money for food. Come over and I will do this and I will give you that money to cook.” So by the time they start the transactional sex, doing work for their teachers or men mostly in power and control, they end up getting pregnant and of course then they leave school. And of course, they become single parents. And of course, they don’t have any opportunity to go back to school. I remember growing up in Liberia and in Ghana where a young girl becoming pregnant… you are told, you are now a parent, you are not able to go back to school. But I’m glad to announce that Ghana has ripped off all those laws thanks to all the powerful women lawyers in Ghana and in Liberia who are constantly fighting to rip up those laws. Because you don’t say, “where’s the man or the boy who impregnated you?” He also doesn’t have to go to school. Why is it only the girls that never go back to school when they have babies? But now things are getting a little bit better. So girls can still go back to school. In the case of my mother, she went back to night school because it’s shameful and because she didn’t have anybody to help her with her children during the day. So she went back to night school before she could graduate from high school because she was teenage pregnant as well. So, those three aspects, you know, of my PhD research work I wanted to highlight.

AA: One thing that we talked about in our introductory episode for this season is that one of my mentors and professors from graduate school wrote a book, and one of her chapters was titled “Who’s Worth Studying?” You know, and poor women and especially teenage mothers, nobody even studied. Nobody asked them what their lives were like, they weren’t anybody’s top priority who got into power. And so we’re so grateful to you and to others who have shined a light on these really, really important topics and helped women and girls especially in these situations to feel like, “wait yeah, my life is worth something. Somebody just asked me research questions about my life and it’s going in a book?” You know, and maybe even just that simple act can help girls and women to realize that their lives are worth something. Well I guess to wrap up our episode, Veronica, I know that you and I had talked a little bit before about what it feels like for you to be a mother and a wife and a professional woman. And I’d love to hear your answer to that question, perhaps as our way to close out the episode. And maybe if you could compare and contrast these roles in some of the different places you’ve lived.

VB: Yeah, thank you. That’s a really, really good place to end because that’s where I’m at. So I’m at this junction in my life where I am struggling to balance this tripod of being a mother, a wife, and a professional. And I’m constantly, constantly struggling with the stereotypical role and I find myself questioning: why have women internalized patriarchy in a way that they raise their sons who become husbands and who become brothers who become corporate managers, why don’t women stop to actually intentionally make an effort to make sure that we are not unconsciously raising young boys to continuously perpetrate the patriarchal society that we are struggling to break down? It’s a struggle, and I find it even more difficult in Canada compared to, say, Ghana or Liberia. I think because this system– or in the US as well, so Canada, US, or Western society compared to Liberia or Ghana– I find that in the US and Canada I struggle most because I feel quite isolated. I don’t really have much community support. I struggle to make friends. I feel I’m not welcome in most instances. I don’t necessarily feel like a proud Canadian, who regardless of my skin color I can still embrace the diversity of people with backgrounds in Canada. I feel quite isolated and I’ve lost the sense of community that I would have in Ghana or Liberia. And so that makes it difficult to balance out child rearing, where you have your community honestly and literally– the village is raising the child, because everybody looks after everybody’s children. And so you don’t have to stay in a house, and if you don’t have a house help you can never be able to go out or spend time on your work or invest in your professional development. In both Liberia, Ghana, and the US I find it quite difficult for different reasons. I find it difficult in North America because I strongly believe primarily because of racism and colonial settlers constantly afraid of Black women, strong Black women taking their power away, taking their place, they’re always intimidated by that. And back in Ghana and Liberia, it’s mostly because men don’t want to give up power. You know, they love the control and they also fear that when women take on these roles they will lose the power and the control they have and society will turn into something else. They just can’t get it into their heads that a woman can be the breadwinner, a woman can lead the house, a woman can make the decision in the house. Or a woman can be the head of the university or a woman can be– and let me correct myself, the first female president of the University Of Ghana is in place, so kudos to University Of Ghana for that.

AA: Awesome, yeah.

VB: [Laughing] Since 1950-something, I think ‘57 or ‘58, I don’t know. But yes, the first female president or vice chancellor of the University of Ghana is now in office. So that’s great. But yeah, those are the main challenges, and what I want to say in closing is, saying these things about balancing these roles, I feel I have a very special and unique opportunity to have a son. And I’m constantly planning and thinking and questioning and reflecting on my role as a mother and what I’m teaching my son so that he doesn’t continue to perpetrate patriarchy. I feel it’s a very special opportunity for mothers. So I make a conscious effort for my son to observe that his dad can do the laundry, can cook, can clean the toilets, and clean the house. And I can also go to work, come and work on my computer, and when he comes to my office specifically he always likes to go for my law books which always melts my heart. I’m like, “why do you like the law books, I have so many other books here!” Why is he always attracted to law books? And I just want him to be able to have that balance. I want him to have empathy, I want him to be kind, I want him to be considerate, I want him to be a partner for whoever he decides to get married to if he decides to get married in the future. And I want him to make those choices based on the fact that his mother has gone through a lot of experiences that are not good for women to continue to go through. So, thank you.

AA: Yeah. Well, that’s a beautiful and powerful way to end. Thank you so much again, Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey, thank you for being here. Thank you for this really complicated and nuanced conversation, and I know I learned so much from your book, and from this conversation with you, and from knowing you. And I’m sure listeners just learned a ton from you today, too. So, thank you so much for being here.

VB: Thank you for having me.

Who raised all you men to sit here and do the things that you’re doing?

A woman did it.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!

This was such a wonderful episode. I am hurt for the women in Africa who are suffering from toxic and deadly practices of rape and oppression. I’m grateful Dr. Fynn Bruey for writing about this and working to make the world better for all women and men.