“If Taiwan is considered a country, its Gender Inequality Index score would have placed it first in Asia”

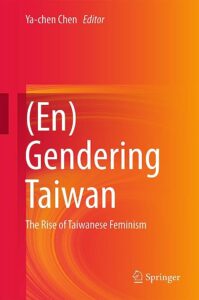

Amy is joined by film-maker Jenn Lee Smith to discuss Patriarchy in East Asia: A Comparative Sociology of Gender by Sechiyama Kaku and (En)gendering Taiwan: The Rise of Taiwanese Feminism, and to explore patriarchy specifically within Confucianism and Taiwan.

Our Guest

Jenn Lee Smith

Jenn Lee Smith was born on the friendly, vibrant island of Taiwan. She is a filmmaker who focuses on women-led stories of underrepresented people. In a previous life, she worked on a PhD in feminist geography. She began her producing career focused on stories at the intersection of religion and sexual/gender orientation, and has since collaborated on BIPOC and environmental films. She welcomes your recommendations for live comedy and films of all genres @bewilderfilm

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Women all over the world find ways to resist systems of patriarchal oppression. For this episode, my reading partner and I read two different books: Patriarchy in East Asia: A Comparative Sociology of Gender by Sechiyama Kaku, and (En)gendering Taiwan: The Rise of Taiwanese Feminism, which is an anthology edited by Ya-chen Chen. And to discuss these works I’m so happy to be joined by my friend and podcast favorite Jenn Lee Smith. Welcome back, Jenn!

Jenn Lee Smith: Hi Amy, thanks for having me!

AA: It’s so great to have you back and I’m super excited for this conversation. For listeners who don’t remember Jenn, she is a writer and film producer. She’s produced lots and lots of films, and Jenn, please feel free to mention some of the projects that you’re working on right now. But at least in the circles that I run she’s best known for the film Jane and Emma and the film Pray Away, both of which I highly recommend to listeners, and many other films. So Jenn, if you want to introduce yourself personally, again you can talk about projects you’re doing but also remind us where you’re from and the things that have brought you to the work that you do today.

JLS: I am a cisgender female, my pronouns are she/her. I also want to mention that the two books that we’re reading, the first being published in 2013, is often used at universities and they’re both pretty technical. And so the first book edited by the Japanese sociologist is the first comprehensive study of Taiwan, China, North Korea, South Korea, and Japan. I enjoyed reading the Afterword, titled ‘A Man Concerned About Gender Equality?’. I think it’s a reflection on how often he is asked why as a man in Asia would he be concerned with gender studies. And we can circle back to that when we talk about his book.

And the second book I chose because I wanted to understand more about my own place of birth. I was born in Taiwan, I emigrated to the US as a child. And some of my earliest memories involved questioning adults on why girls had to be more obedient while boys could be more free to do what they wanted. They could wear pants and climb trees. Climbing trees in a dress is not as ideal, and I understand not all girls want to climb trees but I did. So my questioning and wanting to be more free was problematic for my grandparents and for other family members who practiced a Confucian patriarchal authoritarian tradition. And so as a young child I was labeled bad, like a bad child. In my mid twenties I went to graduate school and I stumbled on these ideas beyond good and bad, you know the binary. And I learned about words and concepts that illuminated ways in which belief systems empowered one gender over another. And so it ignited the feminist in me that I never knew existed.

So for example, in contemporary China it’s well documented that more females are aborted and abandoned than males. And so my master’s thesis dealt with this question of sex ratio at birth. It was done in the field of geography and I looked at where this imbalance was happening the most in China, and I found that places that were less strict on the one-child policy were more likely to have more balanced male to female ratios at birth, specifically. And the education of a woman or her level of income didn’t necessarily impact her valuing sons over daughters, this was surprising to me. Ultimately, it’s the narratives and cultural norms that devalue women and girls in all areas beginning at her birth or non-birth, sadly. So what this has resulted in is tens of millions of boys who won’t have a mate, and this is an ongoing issue in China. But you can understand why when there are Chinese sayings like “It’s better to own a goose than a daughter, you know, the goose you can eat.” Or another saying, “Eighteen daughters as beautiful as goddesses are not as good as one crippled son.” Or more to the point, “nánzūnnǚbēi” (男尊女卑) which means men are in charge and women are basically inferior to the men. There will be more of these idioms in this episode, sadly and interestingly, we need to know our history. On the other hand, today parents are noticing that daughters take care of them just as well if not better than their sons so things are changing, especially in China’s coastal cities.

East of mainland China is the island of Taiwan, where I was born. And so this is why we’re choosing to focus on Taiwan. Another reason is they are just simply a great example of how quickly women can move into positions of power when a government chooses to implement equal and free education to all, when they encourage women to enter politics and save seats for them, and they allow for grassroots efforts by women to flourish. And in preparing for this podcast I’ve been happily surprised at the state of Taiwanese feminism and feminist contributions and ways in which Western developed countries can actually learn from them.

AA: Yeah, that was one of the really exciting and kind of a rare hopeful thing for the podcast that you really discovered was how Taiwan can be a model and things are going really well there. But again we’ll circle back to that later. So the structure of today’s episode will be first the book that we mentioned by Professor Kaku, who does not too deep of a dive in any one country, right? We’ll talk about patriarchal systems in East Asia just in kind of broad strokes. So we’ll do that first and then we’ll deep dive and Jenn, you’ll take the lead on that deep dive in the second half of the episode on Taiwan.

So I’ll start with one of the foundational principles that appeared in both books that we read actually, and that’s the ideology and philosophy of Confucianism. Buddhism and Confucianism are really huge foundational concepts, so I’m going to talk a little bit about Confucianism. Confucius was the preeminent Chinese philosopher whose ideas formed a foundation of thought throughout China and then spread all throughout East Asia. He lived from 555 to 470 BCE, and just for kind of a frame of reference of comparison, this is around the same time as Siddhartha Gautama, who became the Buddha, was living in India, and Pythagoras in Greece. And actually Confucius died one year before Socrates was born. So this is a time of incredible flourishing in lots of different countries which is really interesting to look up. But that was really surprising to me when I first learned about Confucius, that was a lot earlier than I expected actually. So just so we have our bearings, that it was about 500s to 400s BCE. Confucius is credited with writing many of the Chinese classic texts including all of the five classics. And the only book that I’ve read of Confucius is the Analects of Confucius. I read that in my master’s program and I thought it felt comparable to the gospels of the New Testament because it contains philosophical and moral teachings of the master teacher. Kind of in parables and in sayings, and “Confucius said this…” and “Confucius said this…” but it wasn’t compiled until after his death so that reminded of the teachings of Jesus, for those of us with a Christian background.

Some of Confucius’s major teachings include the golden rule, which in Confucianism is phrased, “Do not unto others as you would not have them do unto yourself.” And he also kind of codified and perpetuated the concept of ancestor worship. And in that same vein as ancestor worship, the notion of filial piety. This will come up a lot in our series on Asia. So filial piety, if you think of these words “filial” is from the Latin “filio” which means son. Like “gloria patri et filio et spiritui sancto,” or “write glory to the father, the son, and the holy ghost.” So “filio” in Latin, and Jenn’s crossing herself, haha. But yeah, so filial means son, right? And then piety, like if you’re pious you have devotion. So it’s the sense of children, I mean specifically sons but it applies to all children, should obey their parents. Don’t rock the boat, do what your parents teach you, don’t bring dishonor to your parents by doing something different than they tell you to do. You should honor your parents by doing what they tell you. So that sense of filial piety was really strong in Confucianism. And at the core of these standards is a strong sense of hierarchy. So lower people should not question higher people. And this is within society at large, and within families, and within marriages, and this extends to gender hierarchy specifically. So that’s what we’ll be talking about today.

Women at the time of Confucius were seen as inferior to men and Confucius really kind of leaned in on this hierarchy with two concepts that he’s very famous for. One is called the Three Obediences and the other is the Four Virtues for Women. So the Three Obediences describes the stages of a woman’s life and it says that in childhood girls are to obey their fathers, in adulthood wives are to obey their husbands, and in old age mothers are to obey their sons. And then the Four Virtues for Women concern 1) feminine conduct, 2) feminine speech, 3) feminine comportment, and 4) feminine works. And if you look at the Confucian Four Books for Women, it describes these codes of conduct, speech, comportment, and works, and I won’t read a big long paragraph that I have here, but it’s basically just being quiet and safeguarding the integrity of regulations, keep the rules, keep things in an orderly manner. It says, “guard one’s actions with a sense of shame.” Things should always be done properly, be careful when you’re speaking, and speak only when the time is right so that you don’t make anyone dislike you. And it says this is what is meant by women’s bearing: no silly play or laughter and work should be done neatly and orderly to offer to the guest. So very much in that a woman is to comport herself in the service of others and always extremely modestly and quietly and always thinking of how she’s perceived by others. Again, this does not just exist in Asian cultures as we know from the podcast, this exists everywhere. But this is just highlighting the specific flavor that you get from Confucianism.

JLS: So yes, the Four Virtues of feminine conduct in Chinese is fùdé (婦德), feminine speech is fùyán (婦言), feminine comportment is fùróng (婦容) and feminine works is fùgōng (婦功). Another Chinese proverb from Confucianism (and obviously, listeners, you can probably place my accent as being quintessentially Taiwanese, Taiwan based)– so yes, a woman’s stomach is one to be borrowed is a proverb from Confucianism, because you’re raising a daughter to give away and that’s just the way that this was all structured. You’re wasting food, in a sense, when you’re giving food to a daughter. She’s going to belong to another household someday. So a woman’s stomach is one to be borrowed. Even if a woman’s responsibility is to give birth to a better child, it isn’t to do a better job of raising a child. Oof, that’s a slam. So these are some of these ideas that later changed when it became convenient to charge women with the education of their children, especially their sons.

Fast forward to the 1950s in China with the advent of Chinese communism again. Again we’re focusing on China right now, their ideal of radical equality meant that everyone was a worker. That everyone was needed to progress in this revolution. In his famous report on investigation of the Hunan Peasant Movement, Chairman Mao Zedong in March of 1927, he wasn’t chairman then, but he said that men were subjected to the domination of three systems of authority: the political, the family, and the religious. Interestingly religious at the time which would later change. Women, he said, were additionally dominated by men in the form of the authority of the husband. He said that this was not right and that liberating women from the oppression of the family and their husbands would be a key task in freeing them from the bonds of feudal patriarchy. Now this was said in 1927, so he had another couple decades of revolutionary work before he would gain power. During this revolution he put three concrete examples into place. There was a law that banned concubinage, the selling of wives and child brides. He granted freedom of choice to marry or divorce and it was all based on, of course, heterosexual monogamy. Two, he implemented a dress code with no distinctions between men’s and women’s clothing so they all wore the ubiquitous what’s called the “Mao suit” which is this gray boxy button-down thing. That I actually saw people still wearing and in the ‘90s when I visited China.

You’re wasting food when you’re giving food to a daughter. She’s going to belong to another household someday. So a woman’s stomach is one to be borrowed.

AA: Oh really? Like that quilted jacket and pants. Interesting.

JLS: Yes, oh super sexy. But very warm in the winter, I would say. Yeah, and everyone would wear a similar cap. You know, if you can picture Mao Zedong, everyone dressed like him essentially.

AA: Still in the ‘90s? Wow.

JLS: Yeah I know, it’s interesting. And then the third example was the institution of a community dining hall where women didn’t have to cook meals for their families. Everyone ate in these large halls in order to reduce women’s housework and free them up to work outside the home, primarily in agriculture. There was a huge agricultural push at that time. Yeah, so these dinners didn’t always happen at the best of times. In fact, a lot of his policies weren’t the most efficient or efficacious. You know, it’s not that Mao’s regime lived up to its stated ideals of egalitarianism either. It didn’t, and of course the Cultural Revolution caused massive devastation. Not to mention the “let a hundred flowers bloom” movement, so several of these things caused a lot of death and committed egregious human rights violations as well. But it’s still important to note that Mao and Maoists had those anti-sexist aspirations.

Since we’re still on China and I’m in film, I highly recommend Hidden Letters. It’s a documentary by Violet Du Feng and it’s showing everywhere currently. If you would like to join in with her on Q&As, definitely look up hiddenlettersfilm.com to see if there’s a local showing or a virtual showing. Basically to give a little background, a secret language was created in the thirteenth to fourteenth century in Southern China, in Hunan Province. And it was created for women specifically to communicate to and with each other without the men understanding what they’re saying. So a lot of it was written on fans. If you’ve read the book Snowflower and the Secret Fan, it’s a great fiction read. Ironically, today with the increased global attention to the existence of this secret language that was discovered in the ‘80s, men are exploiting it for their own economic gain. So the film kind of shows this in a way that doesn’t antagonize the men but it really does show how men are exploiting it to make money via the development of apps and merchandise and things like that. And so the film follows two millennial Chinese women who are connected by their mutual fascination with the secret language of sisterhood, they consider it. And their desire to protect it and its original intents. I think Violet does a great job of not antagonizing the antagonist in this film. Power she does show in the film, the men taking over this language.

AA: That’s so fascinating. Someone just recommended Snowflower and the Secret Fan to me just like two weeks ago but I haven’t read it. So I’ll totally read that and that film sounds fascinating, I’m totally going to check that out. Hidden letters film–

JLS: –.com. Yeah.

AA: Okay, hiddenlettersfilm.com. Awesome, I’m totally looking that up.

JLS: Just came out.

AA: Okay I can’t wait.

JLS: Alright, let’s talk about North Korea. So post-Korean War, with a demarcation, the government built childcare centers and kindergartens in order to help women enter the workforce for the same reasoning that Mao did, to boost GDP. Traditional and patriarchal clan units were largely replaced with a nation, back to that idea of filial hierarchy. Within this nation family, the head of the household is the leader Kim Jong Un, he was known as “the father”. And North Korea is still very patriarchal, and it’s just expanded to become a bigger unit. In a 1995 article called ‘Korean Women in North Korea’ they extolled mothers who took joy in sending their sons to the front lines during the Korean war to die for the revolution, and these stories of sacrifice are still being told forty years after the war is over. And basically the message to the mothers is: you are breeders of soldiers whose loyalty is to the supreme leader and father and nation of North Korea. In an address by Kim Il-sung to a national meeting of mothers, “Mothers must bear a very important responsibility in home education. Why is the responsibility of the mother greater than that of the father? It is because it is the mother who bears children and raises them.”

So this was followed up by a subsequent women’s conference when the participants issued a declaration making the following points: Women should put up with a bad mother-in-law and serve her (oh dear); Women should be strong and tolerating a dissipated husband in order to educate or reform him; Divorce is highly unstable and not a desirable step no matter what the reason; And participation in social labor was not a reason to neglect children’s education, to do so was a sign of insufficient revolutionary spirit. So even if you were passionate within your family and social laboring, your job is still to educate children which is reminiscent of the Republican message of mothers in the household, I believe. Amy, did you want to speak to that?

AA: Republican Motherhood in the United States, you mean?

JLS: Yes, correct.

AA: Yeah, it’s a step past where women shouldn’t be educated at all. But it’s just this intermediary step where it’s like okay fine, women can be educated but only so that they can produce educated sons for the country, for the good of the country, right?

JLS: For the good of the country, yes. You’re seeing a lot of these ideals overlap.

AA: Pointing out as you did in North Korea that it’s just like on the macro level as well as the micro level, it is a patriarchy with the person at the top is a man and he gets to dole out the responsibilities, right? “And you will do this, and you will do this” to all the rest of the men for various reasons, and all the women because they’re women.

So I’ll take South Korea just briefly. Again, this is kind of like a bird’s eye view, broad brush strokes, but just as a little bit of an acquaintance and we’ll do a whole episode on South Korea later in the podcast. But I thought one of the interesting things from the book we read was that he writes that specifically in Korea there was really an emphasis on the idea that it was unfeminine to be educated. And so there’s a Korean proverb that says, “A woman who cannot count more than 10 bulls will enjoy good fortune.” So like, I mean, that you can’t count higher than 10 was idealized, the book says. I mean it’s hard to even process. Jenn and I are both, like listeners can’t see, but we’re like ugh covering our faces in horror.

JLS: Haha.

AA: So hard, it’s really hard. So thankfully that ideology didn’t last long, and like we just talked about, eventually Korean women were allowed to be educated in order that they could, you know, have a nice conversation and enjoy literary arts, and educate their children for the good of the country. So we see this happening in lots of different countries as you pointed out, Jenn. And like I said, we’ll talk more about Korea on another episode.

the message to the mothers is: you are breeders of soldiers whose loyalty is to the supreme leader and father and nation

And so I’ll quickly just touch on Japan, which also we’ll be deep diving into. But just to kind of set the stage and give a bird’s eye view of the region of East Asia. In the book one thing that I thought was interesting and that will come up later is the concept of the “good wife and wise mother”. And that’s a phrase that is repeated really often still, apparently it developed in the early twentieth century. And the author is Japanese, so this is Professor Kaku talking, and says that in the early twentieth century Japanese mothers began to revolve around their children completely. There wasn’t a concept of the primary unit of a family being – if it’s a heterosexual partnership – the man and the woman. The man really was married to work and he had his social life and his work life, that was his primary focus. And that the woman just revolved around the emotional relationship that she had with her kids. And Professor Kaku talks about how that can be smothering for the children and it’s not healthy for the woman, especially as the kids grow up and then she finds herself completely lost and with no purpose in her life. Which is probably broadly relatable no matter who’s listening to this. So we’ll talk about that more in a future episode on feminism in Japan. One thing I wanted to mention that wasn’t in the book is that all you have to do is Google “Japanese women opting out of marriage” and you’ll see tons and tons of articles in every major newspaper, international paper, on this story. Japanese women apparently, like the younger generation now who are becoming adults, are fed up with this patriarchal model and young women are choosing to not do what their moms did. And Japanese women are opting out of that patriarchal marriage, not getting married, they’re choosing work. They’re choosing not to do the double burden of working outside the home and being the primary caregiver and the housekeeper and doing all this stuff. So they’re just not having it. That’s a really interesting thing to look up if listeners are interested, too.

JLS: I think it’s fascinating that this author, Sechiyama Kaku, attributes his interest to this topic to his mother because he observed his mother navigate the workforce at a time in Japan when most women did not work outside the home. That was probably my favorite part of the book because it was so personal.

AA: Yeah, totally. Because the rest of the book was really interesting and I learned a lot but I texted you, Jenn, I was like “this is a lot of graphs” haha. It has so much data, which is important but I’m like oh my goodness this is so much interpretation of data and I always love a personal story. So I agree with you, I loved his personal reflection on why he did that work and.

JLS: Yeah, unfortunately the next book (En)gendering Taiwan didn’t have any kind of anecdotal pieces like that that we can relish in. It was a compilation of scholarly peer reviewed articles. So before we dive into chapters that Amy and I are interested in talking about, here’s a very brief history of Taiwan. It is an island off the Southeast Coast of China, it is most famous among linguists as the originator of the Austronesian language. So modern-day speakers of Polynesian languages, all of the Pacific and the Indian Ocean islands, their language can be traced back to the island of Taiwan.

AA: I did not know that.

JLS: Isn’t that fascinating?

AA: Yes!

JLS: Yeah, I would love to look more into that as well. But that is why I think Taiwan has such an interest in preserving its indigenous culture. There’s an actual amusement park that you can go to in Taiwan. It’s called the Formosan Aboriginal Culture Village, and it’s super fun.

AA: Wow! Is it like the Polynesian Cultural Center in Hawai’i maybe?

JLS: It is similar but I would say it’s way cooler. Yes, you do have the shows that they provide but you also have very interactive activities like learning how to throw stones with their ethnic tools. And also I remember picking up a bow and arrow and going, “Do I not have to sign a waiver to use this?”

AA: Hahaha, that’s funny!

JLS: Like I could shoot this anywhere I want. It was a legit aboriginal bow.

AA: Wow, that’s so cool.

JLS: So the indigenous people were there, and then came the Portuguese. From the late thirteenth to the early seventeenth centuries, their presence was felt. However, from the late thirteenth to early seventeenth centuries, Han Chinese crossed the waters that separated Taiwan from China, especially from the province of Fujian. They started settling in Taiwan, and some of my ancestors came from that time, from that province. And they were pushed out. This would be a pushing out of migratory settlement because of famine and flooding of the rice fields. And so I would say it was mostly men who made the trek across the waters to settle on the island and create a progeny with the indigenous women there. The island was named Formosa by Portuguese explorers, and then it was colonized by the Dutch in the seventeenth century.

There were two Dutch missionaries that we have historical records from. Reverend Georgius Candidius in 1628 and from Reverend Robert Junius in 1633. Junius was writing to his boss, the Dutch East India Company and the governor there, and he was saying that marriage wasn’t as fixed as they thought it should be, through their lens, their western Dutch lens. There were no customs such as marriage. What he called marriage wasn’t necessarily marriage because they’re oral traditions meant that their customs were constantly changing. There was too much fluidity happening within their social structures of the Sinkan region for the Siraya. Men weren’t allowed to marry until they were twenty, other sources say that they can’t marry until they’re 42. Women could marry as soon as their families allowed it. When a young man wished to marry a maiden he sent his mother, sister, cousin, or someone of his other female relatives to her house with presents consisting of adornments, textiles, or Chinese import goods. Upon showing them the wedding gift, his intermediary asked the girl’s father, her mother, or other elders of her family for permission on his behalf. If they approved the proposal they could keep the presents and the marriage was considered to be settled without any ceremony or celebration. The following night, the groom was allowed to sleep with the bride.

Now Candidius reveals that newlyweds continued to live in their respective family houses instead of establishing their own conjugal household. The men valued headhunting quite a bit, so they would live in these villages where men specifically trained, they fought on the daily against neighboring tribes and when they won they would cut off the head of the defeated and there was a whole ceremony and ritual around it. And this was the reason why the men lived in their own respective spaces. Now the wife, again through the Dutch lens, had occupations of her own such as cultivating the fields for the benefit of her kinfolk and the young. And the husband kept on residing in the men’s quarter near to his parents’ house during the years he had to fulfill his duties as a warrior. Only after he served out his term in this capacity can the man finally settle down and live with his wife.

Interestingly, they mentioned very briefly that there were spiritual leaders of the Siraya. And they were women! Women were the spiritual leaders and they were also priestesses that performed ritual and ceremony and they were known as inibs. And they appeared to have been the predominant mediators in the Sirayan society between human and supernatural spheres before the Dutch missionaries arrived. So by 1640, the Dutch missionaries had reported that people of that region had converted to monogamous Christian, a.k.a patriarchal marriage. And Candidius confessed that a generation earlier, “they would rather have died than live in this fashion.” But at that moment things were changing and the priestesses who had formed such an obstacle to Candidius’s labor had lost all of their former power. I’m sure he was cheering for this, but Amy’s shaking her head.

AA: It’s so sad!

JLS: It is so sad.

AA: I hate it.

Women were the spiritual leaders and they were also priestesses that performed ritual and ceremony

JLS: Moving on to chapter seven of the book, this one explores factors that promote women’s participation in Taiwan’s politics. And in summary, factors include 1) grassroots women’s organizations had been quite effective in upgrading the status of women in Taiwan overall, 2) the 1946 constitution law that required that women would be guaranteed a minimum representation in legislative assemblies at all levels of government. This was implemented very early on when the Chinese took over Taiwan and this also meant more laws were passed to address women’s issues moving forward. The third factor is that in the mid-1980s, Taiwan experienced a democratic transition and many new women’s organizations were formed, especially on college campuses. These autonomous groups worked to improve women’s situations such as the right to reproductive choice, prevention of domestic violence and sexual assault against women, environmental protection, equity in the workforce around pay, the civil rights of LGBTQ+ couples, and the advancement of women into leadership roles everywhere. The authors note, however, that lower class and less educated women were less impacted by these improvements over the last several decades.

Recently, in a February report this year made by Taiwan’s executive cabinet, they found that the number of female local government heads in Taiwan had reached a historic high of 56.3% after the 2022 local elections. Isn’t that amazing?

AA: Yes, it’s so amazing! It’s crazy.

JLS: So I don’t know if many people know, but Taiwan has a tricky kind of situation on the global stage. Very few countries in the UN recognize Taiwan as its own nation-state, its own governing state. So if we’re using the same metrics adopted as the UN development program’s annual gender inequality index, and by the way this index measures gender inequality based on reproductive health, empowerment, and the labor market. If Taiwan is considered a country, its Gender Inequality Index score would have placed it first in Asia. First! And seventh among 170 countries ranked in the index in terms of efforts to eliminate gender inequality. Yeah, that’s a very important note. Meanwhile, female participation in the private sector of Taiwan also improved significantly with about 586,000 small or medium sized companies, enterprises that are led by women in 2021. And that’s an increase of 20% over 2012’s numbers.

And as of today, here’s another important note, Taiwan remains the first and only place in Asia to recognize same-sex marriage. And Audrey Tang is one of four transgender high level officials in the world. And she oversees Taiwan’s tech things. I’m trying to remember what her official title is [Minister of Digital Affairs].

AA: Only four in the world and for one of them to be in Taiwan is pretty incredible. And like we talked about at the top of the episode that Taiwan really provides an example, I mean even as you were listing all of those things like the gender equity that’s written into their constitution. We’re still trying to get the ERA passed here and it’s been over one hundred years and we can’t even get the Equal Rights Amendment to the constitution passed. So Taiwan is really leading the way not just in Asia but in the world, like you said. And that kind of leads us to the end of the episode. I did want to ask you for a takeaway, Jenn.

JLS: Yeah, I think in reading these books one of my main takeaways is that globally, the education of women is the rising tide that raises all boats. And yes, we can say that Western feminist knowledge has impacted women in East Asia to question traditional Confucian structure and culture. While at the same time, those of us who are in Western culture, we can learn a lot from East Asian women and East Asian best practices, I suppose, of universally free education, when we have these organizations that are grassroots working towards raising women’s status that we give them as much autonomy as possible, and we as women individually recognize that we can be helping each other in our various roles. And I forgot to mention that in Taiwan there are several organizations that promote women staying at home and fighting for the rights of the stay-at-home mother and they are given equal voice, equal opportunity, equal platform. So another thing to learn from, right? And Taiwan is a smaller place and a little more homogenous which allows it to move more quickly I think than a larger country. However, these are things we can be looking at at all scales.

AA: Fantastic. Well I learned so much, I really didn’t know very much about Taiwan to be honest. I think the only thing that I had really known was just about the post-Mao, you know, the Mao revolution and that a lot of people fled from China and Chiang Kai-shek was there. I knew just the very tip of the iceberg and nothing about gender, to be honest. So this was a really, really interesting dive and I’m so grateful for your guidance on this and your personal experiences that you brought to the conversation. So, thank you so much for being here, Jenn. It was so fun to talk with you about this. Again, Jenn Lee Smith, thank you so much for being here.

JLS: Thanks, Amy.

parents are noticing that daughters take care of them just as well if not better than their sons,

so things are changing.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!