“let’s actually use the principles of Buddhism to come at feminism”

Amy is joined by Marissa Lila and Rachel Lam to discuss Buddhism After Patriarchy by Rita Gross and begin our exploration of patriarchy in East Asia.

Our Guests

Rachel Lam

Rachel Lam is a professor of psychology and integrative medicine caregiver in Salt Lake City, Utah. She identifies as a biracial-female educator, healer, and advocate for social justice and mental health.

Marissa Lila

Marissa Lila (she/they) is a Thai-American documentarian who grew up in Hong Kong and Thailand and is now based in Salt Lake City. As a multicultural filmmaker, she directs and produces projects with characters who cross boundaries set by dominant cultures or identities. Marissa’s projects have been selected to play at international film festivals (DOC NYC, Camden, IFF, Big Sky Documentary FF, and MountainFilm). Two projects she produced, Transmormon and Oxygen to Fly, went viral with over 160 million total views. These projects were featured in The Huffington Post, New York Times, The Atlantic, People Magazine, and Dazed. Marissa is co-founder of OHO Media, a creative content agency for which Marissa creates documentaries and documentary-based branded content. Marissa directed, produced, and wrote for the docu-reality television series The Generations Project, for which one of the episodes she produced won a Regional Emmy. Marissa also spent six years creating educational content to increase equitable outcomes for students inclusive of race, ethnicity, language, cultural, sexual orientation, or ability.

The Discussion

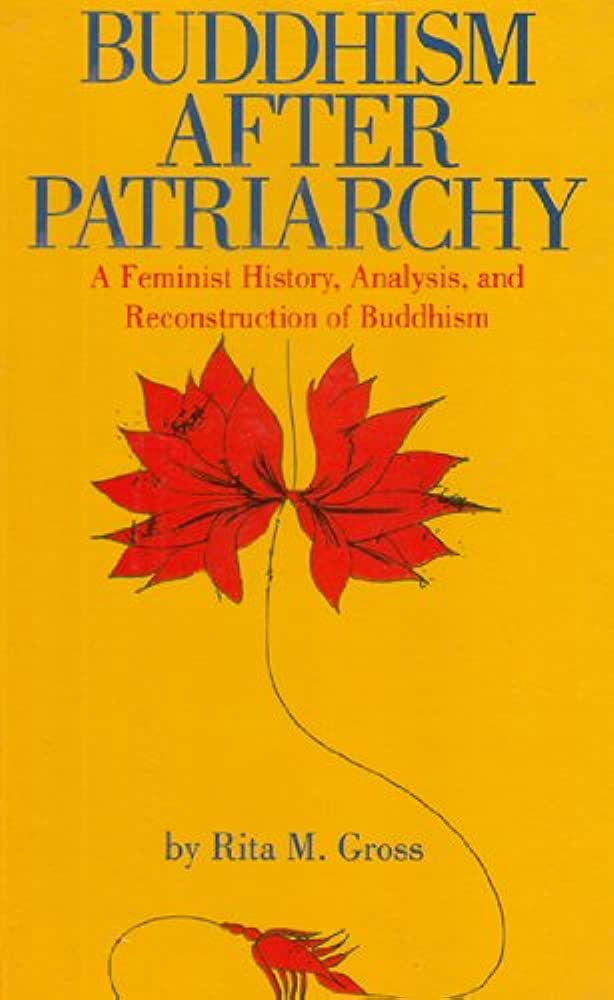

Amy Allebest: Today we begin our series on patriarchy in East Asia. And to lay the foundation for the next few episodes, we’re going to begin with a study of Buddhism. Several months ago I discovered the book Buddhism After Patriarchy by Rita Gross, and this turned out to be one of my very favorite books to read. It was informative, fascinating, thorough, and written in such a smart but accessible style that I would recommend it to anyone who’s interested in this topic. And I’m so, so excited to discuss this book with Marissa Lila and Rachel Lam. Welcome, Marissa and Rachel! I’m so excited that you’re here.

Marissa Lila: Thank you for having us.

Rachel Lam: Yeah, thanks so much. Happy to be here.

AA: So, let’s begin by having you introduce yourselves. I’d love to have you talk about where you grew up, your families of origin, your professional work, your education, and just a little bit about what makes you you.

RL: This is Rachel, I’ll get started. I am a biracial Asian woman. My father is an immigrant from China, he came to the US in the ‘70s and met my mother, who was a blue-collar white American lady. And so I did grow up with certainly some Asian influence, Buddhist influence, because my father came out of the Cultural Revolution and was a complete 100% atheist. My Chinese grandmother, however, was Buddhist, and so as I became older and my dad took her in to live with her, which is very cultural, I did almost absorb by osmosis some of her practices that have become visible to me, that I’ve become aware of lately in my life. I grew up in the Midwest and Arizona, and then ended up in some different places around the world in my career. I was in Singapore for three years, I was in Switzerland, and then here in Salt Lake City, and we landed here about five years ago. So I am currently a professor of Psychology, I work at Weber State University, and I’m also director of a ketamine assisted therapy clinic here in Salt Lake City.

AA: Awesome, thanks Rachel.

ML: I’m Marissa. I am also biracial, my father is from a Danish-British Utah Mormon stock who immigrated to Utah as homesteaders. And my mother is Thai and her whole side of the family are all Buddhist and have been in Thailand since forever so, I’ve come from a very inherently multicultural background. And I’m a filmmaker by trade. I was born in the US but have lived in several different countries including Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Thailand. Most of the core of my growing up was in Thailand, which is primarily a Theravada Buddhist country.

AA: Okay, awesome. And we’ll talk about Theravada Buddhism and the different denominations of Buddhism in a minute. As another introduction before we start, I’ll just say another word about the author because I thought this was really interesting. I’ve encountered Rita Gross in other books that we’ve read on the podcast and have kind of been piecing together like, oh she did this too! So it was really interesting to me.

Rita M. Gross was born in 1943 in Wisconsin. She was raised Lutheran, but converted to Judaism in her 20s, and then to Buddhism in her 30s. In 1974, Gross was named the head of Women in Religion, which was a newly created section of the American Academy of Religion. She earned her PhD in 1975 from the University of Chicago in the History of Religions, writing the first doctoral dissertation ever on Women’s Studies in Religion. And when I read that in the book, I did a double-take and thought that can’t be right, I did not read that right. But I did, I looked it up, and it was 1975 and Women’s Studies programs were not established yet in universities. It was actually Gerda Lerner who was responsible for a lot of the establishment of Women’s Studies programs. So yeah, Rita Gross did the first doctoral dissertation ever in Women’s Studies in Religion.

Then in 1976 she published her groundbreaking article, ‘Female God language in a Jewish context’ and that was published in the anthology Womanspirit Rising, which we covered in Season One of the podcast. In 1977, Gross became a Tibetan Buddhist, and in 2005 she was made a Senior Teacher within Tibetan Buddhism. Gross wrote several influential books during her lifetime. The two most well-known of which are Buddhism Beyond Gender: Liberation from Attachment to Identity and the book we’re going to discuss today, Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism. And I just really loved this book. I thought the content was fascinating, and the writing was incredibly clear and clean. And I found myself thinking a couple of times, “Okay, this is the product of a mind that meditates.” She really is so incisive in her thinking.

And I want to start with a passage where she describes her personal journey. She says, “I was a feminist long before I became involved in Buddhist practice. Quite frankly, I checked very carefully using feminist criteria before committing my energies to Buddhist practice. I was not interested in another trip through a religion so sexist in its symbol system or hierarchical structure that I would inevitably be damaged by it. Somewhat wearily, I committed. But I fully expected feminism and Buddhism to be two separate and parallel tracks in my life. It was unnerving and unsettling when the tracks began to merge and intersect. I believe that Buddhism can make a significant critique of feminism as usually constituted, and that Buddhist thought and practice could have a great deal to contribute to feminists by helping feminists deal with the anger that can be so innervating, while allowing them to retain the sharp critical brilliance contained in the anger. Buddhist meditation practices can also do wonders to soften the ideological hardness that often makes feminists ineffective spokespersons on their own behalf.”

I mean, that was utterly new thinking to me when I read that, the intersection of feminism and Buddhism. And Rachel, I’m imagining as a psychologist you have things that you could comment about those thoughts. But I thought that was a really great way to get into the book, to get into her way of thinking of these things. But let’s start taking turns highlighting the most important parts of the book. And I think we were going to start with kind of a crash course in Buddhism first, for listeners who haven’t had an opportunity to study Buddhism. Marissa, maybe you can walk us through some of the basics of the religion.

ML: Yes, I’d be happy to. So, Buddhism is a nontheistic religion. And even that’s not entirely accurate, but we’ll just say that’s true for right now. But it doesn’t believe in a supreme being, or it’s separate from a supreme being. It has nothing to do with a supreme being. It’s really ultimately about how to free yourself from suffering, the suffering of life. There are four basic principles that are part of Buddhism, and that are called the Four Noble Truths. The first one is the concept that conventional existence is full of suffering. And this ties into the second Noble Truth, which is that ignorance is really about feeling attachment to things that are illusory. So, you’re attached to wealth, you’re attached to power, you’re attached to material things or temporary things in this life. And those things are not spiritually permanent. Then the third Noble Truth is that suffering can cease. So, hey good news! Buddhist teachings show you that you don’t have to be stuck in that suffering, that there are ways, there’s a method that you can utilize to release yourself from that suffering, from the attachment that causes suffering. Which leads to the fourth Noble Truth which is that the path to that liberation from suffering that will lead to enlightenment is laid out for you, and that’s called the Eightfold Path, and we don’t have to go into those details right now, but basically you can follow a path that releases you from that suffering and here’s how to do that. Those are the fundamental truths of what comprises Buddhism.

AA: I’m feeling my heart rate go down and my blood pressure go down, even just hearing and just being reminded of that. Haha. We all said as we started this episode, we’re like “How are you doing?” And we’re so busy, and I was like “I’m exhausted and stressed, how are you?” As you’re talking, Marissa, I’m like oh yeah, I’m attached to illusions, actually. And I need to be better about releasing that attachment. It’s so wise.

Buddhist thought and practice could have a great deal to contribute to feminists by helping feminists deal with the anger that can be so innervating

ML: It’s so practical. That’s what I love about Buddhism, and that you can utilize these strategies no matter what tradition you come from or that you might choose to follow. Buddhism is, at least philosophically, compatible with so many other belief systems. And I really appreciate that about Buddhism.

AA: Yeah, that’s really wonderful. Okay, Rachel, can you talk us through some of the history of how Buddhism was founded?

RL: Yes, so the start of Buddhism comes back to this Indian prince in 5th century BCE Siddhartha, who was essentially kept imprisoned by his family in the palace walls. They didn’t want him to see the sufferings and the dangers and the ugliness of the world out there, so he was never exposed to that. But he was not satisfied with all of what he was in. And he took it upon himself to step out and go into the world. And so the story that I know is that he goes out of the palace walls, he goes to be in the world, he experienced and saw the realities of suffering and death and illness and destruction and he was sort of taken by this. This is how it is out there, you know. And he sort of lived the “homeless path”, or what do they call it?

ML: Ascetic.

RL: He became an ascetic. So he basically starts to live out these principles of detachment from wealth and material things, and in this journey that he’s on he becomes the first enlightened being, essentially, to have reached Nirvana. So I’ll give a definition on that: a transcendent state in which there is neither suffering, desire, nor sense of self, and the subject is released from the effects of karma and the cycle of death and rebirth. So Siddhartha became essentially the first Buddha.

ML: So he was kind of like a Princess Jasmine character–

RL: That’s exactly what I actually was thinking about, honestly!

AA: Haha, I love that!

ML: –who lives this ritzy life, leaves the palace, is in a position to feel the deepest empathy they’ve ever felt in their whole life, and then decides that the way they’ve been living is unethical. And then swings their life pendulum to the other side, and becomes an ascetic. Like he eats this many grains of rice every day, and extreme deprivation, bodily deprivation so that you stay in a spiritual space. But, the changing point for Buddha was when he was an ascetic, he was meditating, and he heard a musician tell a story to a child on a boat. And he hears them say, “If the string is too tight, it doesn’t sound good. If it’s too loose, it doesn’t play. It has to be at the right tension.” And he realizes in that moment that a life of opulence and a life of asceticism are both extremes that are unnecessary, and that the middle path is the most ethical path to take on your journey to enlightenment.

AA: It’s a beautiful and really, really, moving story I feel like. One thing that I want to add here too, partly because we just finished our series on India and we talked about Hinduism, so this is in a Hindu context. He’s in India and so when you referred to karma, right, and the never ending cycle of death and rebirth, you’re being reborn into different circumstances with each lifetime. And so Nirvana would be that state when you finally reach the top and you don’t have to be reborn into higher levels because you’ve reached the highest level, right? Am I understanding that right?

RL: Yes, but also reaching the highest level still makes it sound like it’s within a hierarchy. And Nirvana is the act of totally transcending that cycle, that hierarchy. So you’re given this choice, like you either get bad karma or you get good karma, you’re given this kind of black and white choice. You die and then based on your positives and negatives you’re born with a certain amount of karmic privilege, and then you do it all over again during that life and hopefully you’re getting higher and higher. But the point is not to win karma. The point is to realize that you can release all of that, that whole cycle is something that you can transcend into a different reality where you understand spiritually that you can be released from that cycle. So it’s not about winning karma, it’s about leveling up yourself spiritually so that you can transcend the karmic cycle.

So there are three kinds of schools of Buddhism. There’s the original Buddhism that Buddha started, which is Theravada Buddhism. It’s like OG Buddhism, that’s the kind they practice in Southeast Asia. Then there’s Mahayana Buddhism, also referred to as the “Greater Vehicle” which is a more modern approach to Buddhism, it incorporated a lot more roles for women, it is a major form of Buddhism that became more popularized in Western countries. And then there’s Vajrayana Buddhism, which is more like the Tibetan side of Buddhism.

AA: Okay, wonderful. Well let’s dive into some of the history as Gross presents it in the book, where she starts talking about early attitudes towards women in Buddhist history. So we’ve told the story of Siddhartha, and he’s the first Buddha, and so like any religious story, the religion starts to get organized, people start to convert, and then doctrine starts to be established, praxis starts to be established. Marissa, can you walk us through some of the monasticism, the monastic tradition and those early attitudes towards women?

ML: Haha, yes. So, you have this charismatic visionary who brings this enlightenment knowledge to the people. And people are starting to understand, like, whoa this method works! I really can achieve Nirvana, I really can become enlightened if I follow this path. So at first there’s a number of male followers who are following Buddha and achieving success, and success meaning enlightenment. So fairly early on in the Buddhist organization, Buddha’s aunt, who is a devout follower of the Buddha, wants to become ordained. And she has a sizable amount of women followers who also want to become ordained and devote their lives to Buddhism and become monks themselves. And remember we are in India in the 5th century BCE, where there is a long history of a very rigid caste system, and the karmic understanding that women have inherently less karma than men. As evidenced by them being born as women, who inherently have more difficult, dangerous, less autonomous lives. So that’s the philosophical context in which his aunt is asking him for ordination. And I think at the time, it’s like all of these new things are happening, these Buddhist women are considering something that has never been done before, no one has ever considered this before. And culturally, it’s something that was completely inconsiderable. So Buddha, I guess, considers it for the first time and he is steeped in sexist culture, and also is worried politically about how the women will not be accepted, and it doesn’t make sense for them to become monks where they don’t work and they don’t serve others. And how can a woman not be in a position of servitude? Conceptually it just doesn’t compute as a possibility in the culture that they’re in, and probably in the culture that we’re in now. So, she asks and her request is denied, basically. But she’s very persistent. She keeps asking, she keeps asking, and he keeps thinking about it and keeps coming back and saying no, it’s just too much. It won’t be accepted. But eventually he relents and he ordains his aunt and he ordains her sizable following of women. So yes, there’s a feminist win. But in order to make that happen, they have a separate set of rules that are added for women monks exclusively. So they establish a sexist hierarchy where women can become enlightened, which seems like you’re winning Buddhism, right? But even if you win Buddhism, you still are hierarchically less than even the novice male monks. Like you have to bow to them, you have to defer to them, even if they’re a 12 year-old novice monk and you’ve been studying this for sixty years. There’s still this hierarchy that’s based in sexism.

RL: Yeah, they’re all subject to all males. And they’re below the lowest male.

women have inherently less karma than men. As evidenced by them being born as women

ML: So there is an ordained nun order, but they’re subordinate to all the male monks at every level.

AA: And I think they had eight additional rules. They had all the rules the male monks had, but then eight special rules. And then I remember reading too that there was this, not a punishment, but they said like “well, since women had been permitted to join the order, the dharma would last only five hundred years instead of a thousand years.” So it’s like this cosmic punishment or something for letting women in. So I would imagine that would cause this feeling of always needing to apologize for being a woman, right? Just constantly, even more so than before.

ML: Right, right. But even within this context, in some ways women are getting more power than they’ve ever had. But in other ways it’s still kind of a shame like from our modern lens that even though in some ways there were these feminist wins that were happening within Buddhism, it still wasn’t fair. It still wasn’t equitable by any means. However, one beautiful thing is that even within this context, the ordination of women, so Buddha’s aunt and all of the women followers after her, they started recording their stories in poetry. So there are all of these poems that are about the enlightenment of all of these early Buddhist women. And these poems are collected in a collection called the Therigatha, so the “Psalms of the Women Elders” or the “Psalms of the Sisters”, which is really amazing. It is canonized within Theravada Buddhism, so that’s the earliest form of Buddhism and that’s still practiced in Southeast Asia, including Thailand, where I’m from.

RL: I think that it’s really lovely that there’s this body of work. And it wasn’t just noblewomen or aristocratic women, these are stories of old women, young women, widows, mothers, prostitutes, poor people, all types of women who were these early converts. And that this collection still exists and you can read their poems directly from their experience. So I think that’s pretty special.

ML: Yeah, for sure.

AA: Yeah, that was so special. It was really, really moving to read that and it made me wish that I had grown up with something like that in my faith tradition. Another really interesting thing that I thought from this section was learning about the line of ordination within Buddhism. I didn’t realize it was kind of like Catholic or Mormon ordination, or sourdough starter is the other analogy I thought of, where like you can trace it back pope to pope to pope to pope, or you know, presidents of the Church or whatever. You can trace Buddhist ordination, I did not know that, that was totally new to me. And then Marissa, you were sharing this story of the nuns’ lineage. Can you talk about that a little bit?

ML: Yeah, so, I was looking into ordination because I’m interested in being ordained myself. And in Thailand, it’s a very common practice for men to become monks at some point in their lives. It’s almost a religious expectation, whether that’s for your whole life or for a year or for a week. And as I’ve been in a place of transition and in a lot of healing in my life, I’ve been looking at Buddhist ordination for myself. And as I was researching it at first, it was very disheartening because while there are ordained Buddhist women in some traditions, on the Theravada side they’re traditionalists. The practice is, this is how things were established originally, and we should not deviate from those things because if it was good enough for Buddha, it’s good enough for us. They have more of a puritanical view of how Buddhism should be practiced. So even though Buddha himself ordained women to become monks, and fully ordained women monks are referred to as bhikkhunis. So even though bhikkhunis have existed since close to the beginning of Buddhism’s birth, there are all these rules around, like, you have to have a group of ten bhikkhunis in order to ordain a new bhikkhuni.

And since that lineage has never reached Thailand, that’s always been used as an excuse for why women can never be ordained within the Theravada Buddhist tradition. They feel like that lineage of ordination has been broken, and so the only way that a woman could become ordained is to find that line and maintain that line from the first woman who was ordained by Buddha to now. And unfortunately, those lines were lost. So there’s been a big gap in women’s ordination on the Theravada side. And when Buddhism After Patriarchy was released, they had not found the line. It got lost in Sri Lanka, there was famine and war and genocide that happened that completely killed the bhikkhuni line in Sri Lanka. And so it was thought that the Theravada bhikkhuni line was lost forever. But then more recently, they rediscovered that that line was actually carried on in Taiwan. So that’s really exciting because you have this line that’s maintained and then they were able to send Theravada Buddhists from all over Asia to Taiwan and reestablish the ordination for women. So very, very recently, I think it’s just one temple in Thailand where some women have been able to be ordained and reestablish Buddhist ordination for women in Thailand. That is very exciting.

AA: It’s incredible! So interesting.

ML: So it’s kind of an update from this book and I don’t know but I hope that Rita Gross knew that before she passed.

RL: Yeah, I mean as you were talking I was just thinking too, when you’re in places where men are already in power there’s no motivation to– well, for any of this, it’s like “oh yeah ladies that’s all gone now, it’s lost forever. You can never be what we are, so, sorry!” So I mean there’s no impetus for them to do anything unless they really, really, super care about justice for women, and even the Buddha didn’t. He was begged by his aunt “please let us”, and he was telling them “okay fine, but you have to follow all these rules and you’re still below us.” So it’s interesting, I think sometimes, and I’m sure this will probably come up, I know that it’s actually much more perhaps common is the right word or typical for Western women to want to practice Buddhism and come into it, not really knowing some of this history that’s existed. And so, as we in the West kind of hear about it, it’s like oh, that seems like a pretty egalitarian religion compared to Christianity, compared to Mormonism or whatever. But actually, embedded in the whole history is this oppression of women just all along the way. So to discover like “oh, wait, wait, you don’t have us yet.” That’s the feeling I get, I’m like m-mm, the lineage is still alive, this is still a thing. What an empowering piece of knowledge to have to go forth in this whole process if this is where your tradition lies. So yeah, just some thoughts on that.

AA: So cool. And Marissa, you have to tell us when you’re ordained! That’s going to be such an incredible experience, wow. Okay so, we alluded to this a little bit before already, but earlier Marissa, you talked about the reincarnation cycle and that women were seen as karmically lower than men, right? Like “oh, what a shame, you must have done something kind of bad in your past lives because you were reincarnated as a woman.” I thought this was interesting, this is one of the negative aspects of Buddhism for feminists because Gross writes that this belief can be used against women who don’t have an alternative analysis to question this system and be like “wait, this feels horrible but I don’t know what to believe instead.” She says, “Not only are they told they are only reaping what they have sowed, and therefore have no basis for complaint, they can also be told that if they rebel against the system by trying to change patriarchal norms concerning the treatment of women, they are creating negative karma for themselves.” So they’re just kind of stuck, and that was really sad to me. And one other thing that I remembered from this section of the book, is that she says that in Tibetan Buddhism, the literal word, the very word for woman in the Tibetan language literally translates as “born low”. It’s not slang, it’s not just a local saying or something. She says, “The word carries a conscious social status that Tibetans everywhere recognize as low. ‘Yes,’ they say, ‘a woman is not as capable as a man. She cannot enter into new areas of development or places in the house, she lacks a man’s intellectual capacity, she’s unable to initiate new things. And finally, she cannot become a bodhisattva until she is reborn as a man.” So, Rachel, I’m wondering if you can talk about this a little bit. About this whole concept of I guess switching genders, and maybe actually first tell us what is a bodhisattva and talk about this issue a little bit.

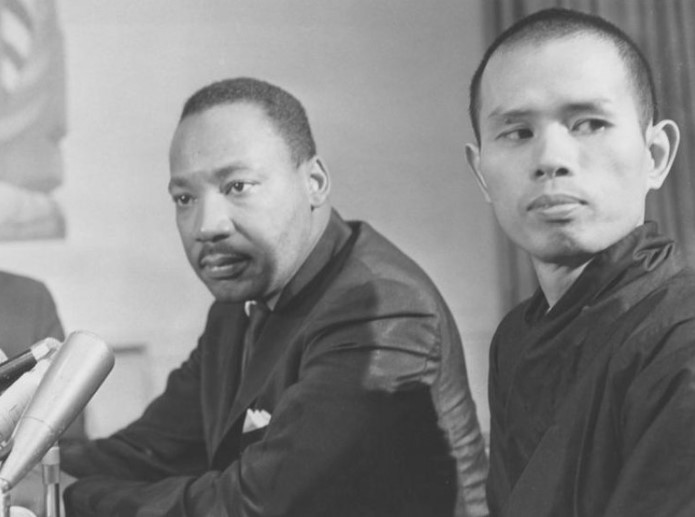

RL: Yes, sure. So what I know of the bodhisattva is a person who gets to a level of enlightenment where they have a purpose, sort of a mission or a life purpose, to specifically stay on this Earth to help people through the sufferings of Earth. So it’s like a decision, they choose this suffering as a particular level or phase of enlightenment at this place because they’re going to essentially help heal the world. So that’s kind of how I look at it. And so, just a little bit of an aside on that, this word struck me in this book because I had first learned of the word from a different book written by a Catholic priest on the friendship between Thích Nhất Hạnh and Martin Luther King, Jr. So, Thích Nhất Hạnh, who was a famous monk with lots and lots of writings who you probably see quoted in all kinds of things, who just passed away recently, like a year or so ago. He had a really beautiful friendship with Martin Luther King Jr., and was devastated by his assassination. And he believed that Martin Luther King Jr. was a bodhisattva.

So that was kind of my prior encounter with this concept and word, so as I’m reading about it in this book Buddhism After Patriarchy, and getting to this place where it’s like, you cannot become a Buddha until you are reincarnated as a man. And so it’s kind of like the best shot women had as women was to become a bodhisattva. So as I was thinking through this, for me, it just felt a little bit like this knife in the heart. Like, oh gosh, you’re limited. We’ll give you some crumbs, here are some crumbs. You know this idea of, especially as you shared Rita Gross talking about that women are inherently lesser beings. Just inherently lesser beings. So you get born into this world, named as an inherently lesser being, and you don’t even have the possibility that you might be an equal being to a man. All the way through to this idea that you cannot become a Buddha until you are reincarnated as a man. That was a powerful part I think for me as I thought through, you know, the existing oppressions we as women still face. And again, back to this idea that I think Buddhism in the West is seen as this kind of equitable space for all genders, there is this rich history of oppression, if I can say it that way, that was just threaded throughout all of everything in this society and in the Buddhist communities.

AA: Yes, that reminds me of the quote I think right where you were just talking about, where there was this debate– and again, it’s like the men debating this, like “can a woman be enlightened or can’t she?” And they’re deciding whether they can or can’t.

RL: Even though there are hundreds of thousands of women saying “we’ve been enlightened.”

AA: Totally!

RL: We can talk about it, here’s all our poetry describing our experiences. And yet the debate continues.

AA: The debate continues. And one thing that they liked to say, and this is a quote from the book, it says: “In all of his rebirths on his way to becoming the Budda, Siddhartha had stopped being reborn as a female quite early before he stopped being reborn as an animal.” So yeah, it says “Many Mahayana texts saw Buddhahood and womanhood as antithetical to each other.” Okay, so let’s talk a little bit more about this scene that I know we were talking about before where there’s a woman I think who’s debating with a monk or someone, and she always confounds him whenever they debate. And he says, like, “If you’re so realized then why aren’t you a man? I’m confused, you should be a man by now if you’re this wise.” And then in one of the variants of this story, it says “The female then magically transforms her body into a male body.” But then in the other variant of the story, “she retains her female body, demonstrating by logic or by magic the utter relativity or unimportance of sexual differentiation.” So there’s this tradition, too, within Buddhism of like, I guess like we said before, detachment from sexual identity, I think that’s one of the titles of Gross’s book. Do you want to talk about that? Maybe does that lead to an openness even today of fluidity of gender within some of these cultures?

Buddhism in the West is seen as this kind of equitable space for all genders [but]there is this rich history of oppression

ML: Haha, I love this conversation.

RL: This is Marissa’s specialty right now.

ML: Well, I wouldn’t say that, but it’s very interesting to me. As a queer person and as a gender questioning person myself, and as a Thai human–

RL: Who is seeking the practice of Buddhism as a lifestyle too, right?

ML: Right, it’s like if gender is something that is changeable within the rounds of reincarnation, that’s established within Buddhism, you can be born a woman, an animal, a man, whatever. These are things that change. Everyone is genderfluid in a spiritual sense.

RL: If you can, as a spirit have a male form in one life and a female form in another then as a spirit, logically that would mean you’re not either…

ML: Right, you’re like gender agnostic.

RL: Exactly, yeah.

ML: So, that’s really interesting. But I feel like it’s particularly interesting within Buddhism because the main goal of Buddhism is to release yourself from the attachment to illusion. You are realizing that your attachment to impermanence, to material reality which is impermanent, to all of these things that don’t have meaning in a permanent cosmological sense. Once you let go of those things then that is part of how you obtain enlightenment and become released from the rounds of reincarnation. So it seems like part of that process is also releasing yourself from the attachment to gender.

RL: Which, what do the men all think about that, right? Who are all talking about “what do we allow women to do?” Well, now if you’re gender equal then this is a very dumb conversation. It’s been going on and on and on for thousands of years.

ML: Right. And it’s interesting because these philosophical conversations happen within cultural contexts where there are certain assumptions that are made like, women are inferior. Period. But then at the same time they’ll have these stories that are about, you know, a little girl or a woman confounding people with her Buddhist knowledge and with her understanding of lived enlightenment. So much so that the impermanence of material reality is something that she can have volition over. Right? She can change her own gender, or she can change the gender of the person she’s fighting with, and demonstrate to them that their gender is impermanent. So that conversation is kind of a silly one to have. I feel like that’s so interesting. I don’t know where else, I mean, I grew up in Thailand so there are concepts of gender that are different in a lot of different countries. What masculinity looks like, what femininity looks like. But it does make me question how visible transgender folks are in Thailand with this conversation within Buddhism with this gender agnosticism.

RL: Yeah, and it’s funny, I’m a little bit in my science mode because I teach research methods and I just finished teaching class, so we were literally talking about logical reasoning. And I’m just coming back to this, like, here’s this tradition that says “here’s the path to no more suffering, we’re going to detach from all these material and conceptual things that keep us stuck on something that’s temporary.” Well guess what else is temporary? Gender! Because you just talked about being reborn as a man or a woman. So why would it matter at the end of it all that you have to be reborn as a man if gender is fluid from the spirit sense. And, Buddhism is all about detaching from these things. So it’s kind of a crazy thing to me.

ML: It’s a little bit of a catch-22.

RL: This is very illogical, right? But yet, who is going to be the ones to press against this? It’s not going to be the men! The people in power, the people of privilege do not know how to not take advantage of their privilege. It’s not human, it’s so much work. So I mean this is my answer to my question that this is so illogical, why does this happen? Well because it’s by the people in power, who are the men, who are saying these things. It’s so curious to me, because when I lived in Asia I visited Thailand a couple of times, and the transgender people are very visible. And I was very struck by like wow, this is really part of a culture which is interesting. 95% of Thailand is Buddhist, basically. And this conversation about gender and the importance of it or what should not be important about it maybe, you can see it in the existing cultural space. It’s visible. Gender fluidity is more visible in that space.

AA: For sure. I know I’ve been reading a lot of quotes but I want to read one more that came to mind because it kind of encapsulates this. There’s this conversation in what’s called a “goddess chapter” in one of the sutras. And there’s this man who’s having a conversation with a goddess. And the man says, “Why don’t you change your female sex?” And she says, “I have been here twelve years and have looked for the innate characteristics of the female sex and I haven’t been able to find them.” So I kind of love that conversation where it’s really important to him that there is this binary division between male and female, and if you’re a goddess then why haven’t you changed? You would want to be a higher incarnation, right? And she’s like dude, there are no differences. So I loved that part. Okay, let’s wrap up. If there’s anything that you feel like you wanted to talk about that we didn’t.

RL: I mean my message to everybody is like, be aware of what we live in. We live in a patriarchal society in America. As things are changing, which I do believe they are. I do believe there is a movement right now of I will call it the divine feminine, of women coming forth in leadership positions, of women stepping into power, at least in my lifetime, to a more visible degree. So I think sometimes what you learn, just in a very general sense, is that we have been living across the entire world in so many spaces in oppression as women. And what do we learn particularly with Buddhism? I still come back to some of the stuff that Rita Gross talks about, which is that it’s more accepted in the West and you see more women practicing Buddhism or whatever. But we have to go back to this history and recognize where it’s come from, you know, just like now, just like my particular tradition in Christianity. Good Lord, how many times has the Bible been used to oppress women? That cultural voice of oppression against women is so incredibly strong still today, and it always has been. I mean that feels like a despairing kind of message, but I think the hope is that here we are having this discussion. Here you are doing a podcast on patriarchy and how it affects everything that we live as both women and men, but it hurts us. But it’s different for us on the side of oppression.

ML: Yeah, I guess for me I’m thinking about how we’re often taking a feminist perspective and applying that feminist lens to all these various disciplines that perhaps was lacking a feminist perspective before. But I think it’s really interesting to apply a Buddhist perspective to the feminist school of thought, too. Like taking mindfulness lessons, taking lessons learned from meditation and being able to clear your mind of what isn’t important and what is not meaningful, and focus on what is meaningful and what is permanent and what is spiritually significant. I feel like that is how you move forward in Buddhism or any religion with a more feminist and equitable lens in general. And I really love this quote where she talks about the main point of Buddhism is the co-humanity of she says “both women and men” but it’s really of everyone. So understanding your co-humanity, like your co-humanity is spiritually significant, that’s one of the spiritually significant things. I feel like we can debate all day about this concept that Buddha said, or this method we utilized five thousand years ago, but the fact is that even Buddha said when women were ordained that the dharma, so Buddhist teaching, was only ever supposed to last for one thousand years. And then it suffered a little bit because they added women to the sangha, to the Buddhist body, so then the dharma, Buddhist teaching, got cut in half from a thousand years to five hundred years. So we’re already millennia beyond that saying, and no one’s having trouble with that technicality. So it seems like there’s all kinds of examples, including the existence of Buddhism itself, that is bucking the technicalities of things that Buddha said already, so let’s make it work for people! Haha.

RL: Yeah, yeah, right. Let’s actually use the principles of Buddhism to come at feminism, at all of this stuff. And I’m thinking again, this idea of transcending any and everything: male/female, material things, wealth, whatever, whatever, whatever. So yeah, that’s a good word. I think that’s a good word, Marissa.

AA: Beautiful. Well, thank you so much for being here, Marissa Lila and Rachel Lam. I so appreciate your time. And thanks for reading this book with me and having this conversation today, I really enjoyed it.

ML: Thank you.

RL: Thanks so much.

the main goal of Buddhism is to release yourself from the attachment to illusion

part of that process is also releasing yourself from the attachment to gender

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!