“We’re in it for the long haul”

Amy is joined by scholar and author Dr. Karen Jo Torjesen to discuss her book, When Women Were Priests: Women’s Leadership in the Early Church and the Scandal of Their Subordination in the Rise of Christianity. This discussion covers the overlooked history of women as bishops, patrons, and more, as well as the masculinization of the church and how the struggle for women’s ordination continues.

Our Guest

Karen Jo Torjesen

Karen Jo Torjesen, Ph.D., is the Margo L. Goldsmith Chair of Women’s Studies and Religion at Claremont Graduate School in California, and an associate of the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity. She is widely regarded as a leading authority on women in ancient Christianity.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: I just finished the book When Women Were Priests: Women’s Leadership in the Early Church and the Scandal of Their Subordination in the Rise of Christianity by Karen Jo Torjesen, and we’re going to start today’s episode with a quote from that book.

“Women’s leadership in Christianity is a dramatic and complex story, one in which the radical preaching of Jesus and deeply held beliefs about gender sometimes melded and sometimes clashed. Jesus challenged the social conventions of his day. He addressed women as equals, gave honor and recognition to children, championed the poor and the outcast, ate and mingled with people across all class and gender lines, and with bold rhetoric, attacked the social bonds that held together the patriarchal family. When Jesus gathered disciples around him to carry his message to the world, women were prominent in the group. Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, and Mary his mother are women whose names survived the retelling of the Christian story in the language and literary conventions of Roman patriarchal society. Paul’s letters reflect an early Christian world in which women were well-known evangelists, apostles, leaders of congregations, and bearers of prophetic authority.”

So my question is, what the heck happened? And to answer this question, I am thrilled to welcome scholar and author of this book, Karen Jo Torjesen. Welcome, Karen.

Karen Jo Torjesen: Thank you very much.

AA: I’m so excited to have you here. And as usual, I will introduce you with your professional biography first and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourself a little more personally afterwards. Karen Jo Torjesen is a professor emerita of religion at Claremont Graduate University. Her research interests include constructions of gender and sexuality in early Christianity, authority and institutionalization in the early churches, hermeneutics and rhetoric in late antiquity, and comparative study of Greek and Latin patristic traditions. At Claremont, Torjesen founded an MA and PhD program in women’s studies and religion in 1990, and collaborated with Jean Schroedel in political science to design an MA in applied women’s studies in 1995. Torjesen taught and developed graduate courses on gender, religion, and transnational feminism. That’s just a very brief kind of tip of the iceberg intro, Karen, and I’d love it if you could introduce yourself by telling us where you’re from and some things that brought you to the work that you’ve done in your life.

KT: That may have been the most difficult assignment you gave me to put that together. But as I did I realized that I can see where the connections are, so I’ll try to tell it in a way that illuminates that. The main issue was my childhood. I had a very unusual childhood. My parents had a farm in the country in Salem, owned a printing shop, and were leading an ordinary life. And in 1952 they dropped out, long before the rush, and sold everything. And we leisurely drove across the country, sightseeing in the 50s. And in ‘66 we ended up in Florida, we bought a sailboat, and sailed in the Bahama Islands for a while, all of that was grand. Then we briefly lived in Costa Rica and Guatemala, and then finally settled in the southern part of Mexico in a town called Oaxaca, where I was off and on between ages 7 and 12. So, my background has a very powerful cross-cultural dimension to it, and it’s that dimension, I think, that shaped me into the kind of scholar I was later to become.

While I was living in Mexico our parents sent us to Mexican school, and we sat in Spanish-speaking classrooms until we could understand Spanish. And that’s how I learned Spanish. And the experiences there in those years, one of the most illuminatory, the story I like to tell the most, happened probably around the age of eight or nine. I was visiting a colonial church called Our Lady of the Sorrows, which is a church to which a lot of the indigenous people come that go all the way back to pre-Hispanic traditions, the Zapotecs there. It was also a colonial church, so it was dripping with gold and filled with figures of saints. And I was an evangelical Protestant, so I knew that this was all wrong, that this was a very wrong form of Christianity. But I remember sitting in front and I watched the indigenous people come in and make their prayers, be in their spiritual moment with the saints and the openness of the child is what I had foreseen. And I remember realizing, “Oh my, they really encountered God here!” And then I had to revise everything that I was thinking about dripping gold in a church and saints, and it’s not issues that I solved intellectually, that would come later, but it was the clash of those different paradigms and countering all this difference. And then as a child, listening for that deepest truth in things that a child sees before we see the world through a dogmatic lens, which of course as an academic I was able to develop to a high degree later on. But I always went back to that moment because I realized that almost every academic interest and pursuit, from violence against women to multi-religious to colonial encounters, all of that, I can trace back to those years in Oaxaca. And that’s what I saw when I visited that church again. So that’s an echo that I think you will hear strongly through my approach to the question of when women were priests (or were they really, as lots of people put in as they read the title).

My college education was at Wheaton College. I wanted to go back to Mexico as a medical doctor, so I did pre-med. I was pretty good in biology so I ended up majoring in chemistry. And as a result, my grades weren’t good enough to get into medical school, so that was off. I got married on graduation weekend, my husband was a philosophy student and going on for his PhD in philosophy at Claremont, actually. And so he said, “Well, what are you going to do?” And I go, “I don’t know.” Of course, I knew that what you do is support the guy who’s going to graduate school by working some job like a secretary. But he said, “You should really think about graduate school yourself.”

AA: Wow.

KT: Which I hadn’t, and I thought, “Well, okay.” He said, “What would you study?” And so I thought about it, and I have to study something I really cared about because you have to care about it the rest of your life. So I thought I’d like to study early Christianity, and that’s how I set out on this degree. When I got to Claremont, I gradually enrolled in classes and then degree programs, and did early Christianity, got into the PhD program, and I studied under a professor from Germany. He was teaching the Fathers of the Church, and he was a fairly eminent scholar in that field. And one morning when I went to the mailbox, in the little mountain town called Mount Baldy, there was an airform there that invited me to become an assistant of his at the University of Göttingen, in Germany, to teach and finish my dissertation. It was an incredible offer, but I had to be able to speak German and study in German. Haha!

AA: That’s not a small detail.

KT: No. I had passed my German reading exam when I was a full-time secretary putting myself through graduate school, so I’d only memorized a thousand flashcards that I had on my desk. I didn’t even know grammar, so that was a challenge.

AA: But you did it?

KT: But I did it.

AA: Oh my gosh.

KT: I was five years there, and I learned an immense amount. I mean, to be participating in the study of religion in Germany, that was the Mecca for our field in that decade. It was an amazing experience.

AA: Sorry, I have a question. Did your husband come with you then? Did he pick up and come to Germany? How did that work?

KT: Yes, well that worked because he was writing his dissertation on Karl Barth, and so basically I’d offered him a five-year fellowship to write his dissertation for the small price of learning to cook.

AA: I love that.

KT: So it worked out. It worked out really well. I got my degree and attended conferences, and gave papers, and because of the tremendous opportunities I had, I became a fairly well recognized scholar. Because your genealogy is what counts in Europe, not so much what you’ve published but who you’ve studied under, and so that was a great asset for me. I wrote my dissertation on Origen of Alexandria, a city in Egypt, and he was the first Christian theologian, the first philosopher to actually do a systematic version of Christian ideas. When I got back to the States, and through my connections in Europe, I got a job immediately. I gave a paper at a conference– I was interested in the organizational forms of early Christianity, so I was starting to think and write on those, and then I was interested some in women. And when I finished giving that paper, it was the first time I’d given a paper in the States, I had several publishers show up and wanted to know if there was a book length version of what I was doing. And I thought, “Oh, publish or perish! Alright, I’m going to go into a new field. I’m going to go into the field of women’s studies in early Christianity.” And so I changed my direction. And what I was hitting was the beginning of that controversy over the ordination of women. And as I listened in on that, all of those who were opposed to women’s ordination were citing not just the Bible, but mostly they were citing the church fathers. The theology of the Fathers.

AA: What year would this have been, Karen? And was this a controversy over women’s ordination in the Catholic Church or were there Protestant denominations that were talking about it, too? Was this throughout Christianity? I don’t know that I’m familiar with this phase.

KT: That’s right, I realize there’s a generation between us. Well, that makes sense, I need to explain that. In the 1980s, women were for the first time being admitted to theological schools to study religion. And in the US, a PhD in religion was very problematic because secular universities didn’t want to get involved in simply catechisms. And so what that meant was there were no women scholars.

AA: Of theology?

KT: Yeah, of theology. And so when the movement began, it came out of the movement for women’s ordination, that’s why it shows up in the ‘80s, because that movement is just getting strong. And it’s across denominations, it’s women from every denomination. What the publishers told me when I talked to them, they said the women in the public are so hungry for any information about women. Liberal, conservative, doesn’t matter, there’s just a huge hunger to know. So that’s why I got that kind of response from publishers, because that’s what was happening in popular culture. And it was also going on in Europe, I know in Germany and other places as well. So that was the backdrop. And I had, for the first time, tools, and other women did too. I could do Greek, I could do Latin, I knew the church fathers. So that’s what made it such a powerful time, because it was a convergence between academic women and women in churches, women in society, women who felt like they had a calling to some larger form of service within religion that was continuously suppressed. So, that was the environment.

AA: I see. Wow. That must have been really exciting.

KT: It was very exciting. And it was very contentious. The resistance was huge, as you can imagine, because it was against tradition, against paradigms, and against the location of power at that time. And so, you can get beat up pretty badly in that process, and so it took real communities of women to stand fast as we were doing this work. So that’s the background of my own education and experience that shapes how I’ve come to the questions that I started to try and answer in the book When Women Were Priests.

AA: Well, that’s wonderful. I’ll just add one more topic really quickly, because as you and I were getting to know each other, and I knew you were at Claremont. We mentioned in our conversation that I come from an LDS background, and I said that there’s Mormon studies at Claremont, right? Can you tell the listeners what you told me?

KT: Haha, I really am coming out of the closet. Well, what I told you was that yes, I had started it myself. I was Dean of the School of Religion at the time, and it was after the political crisis of 2011. And so we were dealing with religious conflict and religious tension, and we were an academic university. What were we going to do about it? And so we decided we needed to be more than a place where you go off and study esoteric things. We needed to be a university where the various religious traditions, not just Christianity and Judaism, which were normally taught and where those religions engaged each other, and we needed to be a place that members of those religious communities could call home and could find their tradition in conversation with other traditions. And in that process, one of my Women’s Studies of Religion students who was Mormon said, “Why don’t we do a chair in Mormon Studies and a counsel in Mormon Studies.” And the more I thought about it, I thought, “Yeah, she’s right. Let’s go.” And so she and I set out, and eventually that’s where we ended up.

AA: I think it’s one of only two Mormon Studies programs in the United States, is that right? Was it the first?

KT: It was the first.

AA: Well, I really appreciate it. I know several Mormon feminists who were either educated at or have taught, or with connections to Claremont and I really appreciate that, Karen. That’s meaningful to me personally. And it’s nice because there’s a lot now that I don’t have to explain about myself to you!

KT: Haha!

AA: Ah yes, you know that. Well, that was a fabulous introduction, Karen. Thank you so much, and I’m really excited to dig into your book. I learned so much from this book and I really highly recommend it to listeners. I think maybe a good place to start would be the backdrop, so I thought we could start with the time of Jesus himself. If you could acquaint us with who Jesus’s women followers were and then how their stories were recorded or weren’t recorded.

women in the public are so hungry for any information about women. Liberal, conservative, doesn’t matter, there’s just a huge hunger to know

KT: Alright, that’s a great place to start. I gave some thought to that as a category, that very early part, when it’s Jesus and his disciples. It’s in the first century, so much of our material comes from the second century. And I have a piece that I have used before, Luke 8:1-3, and Luke begins by saying that Jesus was traveling in this area with the twelve disciples and there were some women with him. That evokes an image. There you see Jesus and then you see around him a cluster of hardy working men, carpenters and fishermen, following him. And then a little bit off in the distance, you see a cluster of women. And not only that, but Luke gives an extensive introduction to this class of women by saying that these are women whose demons had been cast out and who had been healed. So he’s already defined these women, they’re morally a bit questionable, but they have received benefits from Jesus and they’re there. So that’s where we start.

Now, what I want to do is take that scriptural piece as an introduction to how do you read a text? The way that we’ve been taught to read the Bible is like reading a law book. What are we supposed to do? And I came to it, now, as a historian. I want to know the context, I have all kinds of questions. Who’s the writer and what’s the writer’s perspective? And why, and what are all the politics behind this? And so that question opens up some interesting counter views. So, the women are Mary of Magdalene, the wife of Herod’s steward, a woman called Susanna, and the King James frees and they ministered to him from their substance. What they were, is they were women of higher social classes than the disciples. And that seems pretty common in early Christianity, that women were especially attracted and especially women from the higher social classes. So what that meant was, for example, with the wife of Herod’s steward, she had connections all the way to the top of the government. So if Jesus got into trouble with the police or with authorities, there was a woman there who had the backdoor channels and could take care of the problem. These are women who had financial resources. The story that just precedes this is the woman with the alabaster ointment who anointed Jesus’s feet. And it was such a costly ointment, and that indicates her social class. And she performs this ritual and prophetic act.

So when you look a bit sideways at the context and ask more questions, what emerges is women not only being present, but women being in highly significant roles, really influential for reasons we would understand. Social wealth, social status, social mobility that these women had in traveling. If you’ve done any fundraising, you know, they’re your main members of this group and you’re most concerned about their needs and keeping them committed to the cause. They’re important in those ways. So I wanted to pick an example of the stories we inherit and other ways of reading, which we learn in graduate school. So that’s the beginning, that’s an illustration. And we can go on and then say, alright, so what’s happening with these descriptions of demons cast out and the woman with the ointment? There is always a sexual innuendo behind these. Prostitute gives you that, the woman with the ointment, that’s implied in that she’s out in public. Where’s her husband? What’s she doing here? She doesn’t belong. And that we’ll talk about later, but that organization of society into public and private, so that women who were active in the public sphere were most vulnerable to accusations and innuendos against their sexual behavior. And that’s one of the ways then that you can disempower women, and those designations you’ll find especially in Luke. Most of the women are described as influential and important, but with some flaws that undermine their authority.

AA: That’s really interesting. I think it’s so interesting that you say if you look sideways at it, or if you have the training of a historian to read between the lines of what’s there, then you can see like a whole different image emerges. But yes, what we inherit, at least what I inherited from reading the words without any of that academic training was what you talk about in the book where you get these accounts written by the men. And like in Luke, you point out that Luke reports that the women delivered their message to the rest of the disciples at one point, but Luke writes, “But these words seem to them an idle tale and they did not believe them.” It’s right there, where the men are like, “Oh gosh, so annoying.” Rolling their eyes. And then you say too that Paul talks about how when he is giving the account that Jesus had come back and was appearing to people, that Paul says, “He appeared to Peter, then to the 12, then he appeared to more than 500 brethren at one time. Last of all, he appeared to me.” And you point out Paul is omitting that the very first person that Jesus appeared to was Mary. It’s attested in all four Gospels and Paul just completely neglects that part. He’s like, “Let’s see, who did he appear to? This guy, this guy, 500 other guys, and then me.” And forgets there were even women there. Just how it was recorded is so androcentric, it’s just so masculine. But I appreciate the expertise that you bring to this and say that actually there’s also this whole other kind of subtext that you can unearth. This is fabulous.

Let’s move on to Mary Magdalene. Maybe we can zoom in on Mary, and we have done a full episode on Mary Magdalene and we could do that again right now, but maybe we’ll spend a minute on Mary Magdalene and how she was recorded and what her significance was.

KT: Yeah. It’s interesting, if you asked somebody who’s been reading the New Testament, who’s the most significant woman? It would be her. It’s easy, it’s the name you heard the most. Who’s the most insignificant man? It’s Peter. That’s the male name you hear the most. I mean, you can tell where the influence is in that simple test. So with Mary Magdalene, we have a woman who has been a witness of the resurrection, the first one who was commissioned by God, Jesus himself, to carry the message of his resurrection, the message of his gospel to the brethren and to the world. So she is now designated as an apostle, one who is sent, and she is a teacher. This is the figure that we have from The New Testament writings and variations between the various writers for their particular agendas. In the late second century, we also have a Gospel of Mary. So the traditions around Mary were so strong that there is even a gospel attributed to her, which focuses on her in those roles of being an apostle, of having been taught by Jesus, and therefore being a teacher and being a prophet. And one of the things that I like, that’s so valuable for me in the Gospel of Mary, is that you see spelled out the gender conflict. Because Peter says, “I don’t think these are Jesus’s teachings. Would he talk to a woman more than he would talk to us? I don’t think so.” And then another apostle intervenes and says, “Peter, you are always quarreling with the women. Why don’t you just listen to her, and we will go and do as she has said.” So, this is a story within the Gospel of Mary that illuminates the social context, that is the rivalry between Peter as a recognized leader, and Mary Magdalene. So, obviously, this group that used the Gospel of Mary felt that Mary’s leadership was more important. But there was a contest between those who favored Peter’s leadership and those who favored Mary’s leadership, and you see it echoed in many places. And so what I learned to see is that gender was a big issue in the early community. And precisely, I think, because so many women were attracted to it, and they played influential roles. And so you had a cultural conflict around that.

AA: Wonderful. Well, let’s go to a different aspect of the gender conflict that we see. We have, obviously, Christianity emerging out of the Jewish tradition. And then one of the other huge pieces of the social context is the Greco-Roman tradition, right? The Romans controlled Judea at the time. And I think that the people living in that area of the world had actually been Hellenized for a long time, too. So the Greek tradition had really, really influenced even devout Jewish people at the time. So maybe we can talk about the Greco-Roman tradition and how this would have influenced the early church and how they saw gender.

KT: That’s a really important question, and the most significant piece to start with is that none of us were trained to ask that question. Who are the scholars who can ask questions about that? They’re anthropologists. They study gender, they study it in a systematic way, they study it in an academic way. And then the other discipline that you need to know really well is sociology. Where are you going to find sociology of first-century Judea or second-century Judea? So that’s to say two things. One is that scholars of religion were not trained at all in these ways and not able to ask those questions. When you start looking at women, you start asking those questions but there are no tools to answer them. So what I did is I started reading anthropology and I started reading sociology because that’s the only way I could have tools to answer those questions.

Now, what has happened to the field, which is really exciting, is there’s lots of other people like me who did the same thing. And so there’s been now a whole generation of scholarship that draws on anthropology and draws on sociology and brings that into the discussion of theology and of the history of the leaders, and so on. So, that’s where I started. And I looked specifically at the gender systems in the Mediterranean, contemporary, because it’s very difficult to see anything studied historically. And to make that connection to my own history, suddenly I was back in Mexico. And I understood the way the gender system was described because it was so much what I experienced as a girl child living in Mexico, because it’s a cultural system that came from Spain. And so it connected, interestingly, to early Christianity. And that was a valuable piece of my cross-cultural growing up.

So, there’s two significant pieces of the Greco-Roman gender system. One is the division of gender roles in terms of public male space and private female space. For example, for a girl to be out without being accompanied by a man or a guardian, she was already sexually indiscreet and subject to harassment. And so the streets, in a sense, are patrolled so that women are uncomfortable. They know that they don’t belong unless they have a male guardian with them. So that’s the situation we have in the ancient world, the Greco-Roman world. And that excluded women already from public spaces, just to be in them, and then more importantly, excluded them from all the realms of power. So, for women to hold office as an administrator, for women to hold church office, is to be exercising a public power, and therefore, a male power. And the role of women was the domestic space. Now, that was a wide space. It was wider than it is for the American nuclear family. The household was the center of economics, and so it was management of both agricultural production and management of crafts production, weaving and dyeing. And women heads of households managed the slaves, which were the staff. So they educated, disciplined, exercised all the kinds of powers that were exercised by male leaders, but within the households. So that’s the first major dimension.

And the second one is the role of sexuality. And that is that male honor is defined in terms of political achievements, offices held, public acts, like we would expect. A woman’s honor was her reputation for chastity. And there are lots of stories about women’s chastity and how they sacrifice their lives to prove their chastity. And so a woman’s honor is her shame. So that restricted women in public roles because of the way the innuendos of sexuality would undermine their authority and their character, and they would also have little access to the roles of power. Now, women did exercise power through patronage, which was a more private role, but it was a significant mode of power for them.

AA: And by patronage, I remember from the book, that means kind of charity work, right? They would get involved with doing good in the community. Is that right, or am I not remembering?

KT: That’s part of it, but actually I should explain it. This is now sociology. Patronage was a really important part of Greco-Roman society. The members of the upper classes would take under their wing people from the lower classes.

AA: Ah.

KT: So I tell my students, you know, your son needs a scholarship to be able to do his education, so you go to the patron and you ask for help, and it’s a lifelong relationship. And the patron says, “Yes, I’ll fund that.” And so the exchange is that the client, the one who is receiving the patronage, is the one who gives honor, and it continually burnishes the reputation of the patron. They’re there in an entourage whenever the patron is moving across town, and can call on these clients, “Come and be part of my entourage so people see how important I am.” So it’s a long-term, lifetime relationship, and it’s a form of redistribution of wealth. Because that is how you get help, how you survive, is by being a patron. And you can see it’s at all social classes within the upper classes, there are patrons that are more wealthy and more powerful than people who are in the lower social class. But that was a role that was not gendered, and women played that role as much as men did.

AA: So they maybe should have been called matrons.

KT: Yeah, but that means something different, you know what I mean?

AA: Haha, yeah.

KT: Yeah, that’s not a good word, sorry.

AA: Okay, so this was such an important and new concept for me. And especially what you said just a minute ago about women’s roles at home, I guess I had kind of associated that more with the American concept of the housewife, where they kind of kept indoors all the time and only took care of their children. Like maybe they were bored doing their embroidery like in a Jane Austen novel, or something like that. And you spend quite a bit of time talking about how it was actually a full-time job. And we have talked before on the podcast about oikos being the root word of “economy”. So these households were producing, they owned farms, they were doing agriculture, selling wares, so household management was a big responsibility that women had. They had a lot of authority but it was constrained to the home. And so that was such an important foundation for me to then understand the next piece, which was house churches. I wonder if you can tell us, I guess maybe another piece that we would need to understand is how Christianity was practiced in the early days, and then why it happened in the home.

KT: Okay, I’ll start in the early fourth century with Constantine. Most people know about him. He converted to Christianity and he created the first Christian church building, and what he did is he selected the basilica. The basilica was a Roman hall, often a judgment hall, as you know it’s architecture because they’re modeled on this Roman model of a public building. And that expressed the power and prominence architecturally of Christianity in the Roman world in the fourth century. Up until then there were no churches, architecturally. There were no churches.

AA: For like three hundred years. You’re saying that for more than three hundred years there were no Christian churches.

KT: To understand, I was really interested in this early period and I did a lot of courses on early architecture, Roman architecture and treatises on architecture, I went to excavations. I mean, it’s fascinating. And then I incorporated that in my teaching, so that was really rich. The early Christians met, for the middle class, those who could be patrons, they met in the homes of the patrons. Their homes were large enough. But Christians in the early period didn’t belong to those classes. They were in the lower classes, and so they met in the shop. If you know a little bit about Mediterranean architecture, you know that on the ground floor of a building you’ll have a shop on the street and then living quarters behind it. That’s how the working class lived, and that was the space of the house churches. They were in those spaces that Christians lived in, and so the group that gathered there would choose their leaders. And the person who was most influential was the person who owned the house and who could provide more protection and more resources for that little house church. They would pray, they had the Old Testament translated into Greek, the teachings of the gospel were spread, there were prophets who’d come through and teach. But then it was the simple process of reading, each person giving their interpretation, a shared meal, and that was the center. And that continued up through the fourth century.

Now what happened, as a house church got more prosperous, then more rooms would be added. And eventually these house churches, when they got really crowded, the owner would move somewhere else, have another house, and then that house would be exclusively used for the Christian community. It would include a baptistry and places for people to spend the night when they were traveling. So you see that the functions of the church were really the functions within a household. And the second stage is called the domus ecclesia, which means “the house of the community”, where it’s exclusively used for Christian worship. So, what that means is that the social world of early Christianity was domestic and therefore followed the patterns of domestic gender lines. And in the household, there are ancient treatises in Greek and in Latin discussing the household and the important role of the head of the household, who is the woman who’s in management. And as the classes got higher it was a disgrace for a husband to involve himself in the matters of the household. And the same words are used. Households are ruled by the woman head of household.

AA: That was a huge aha moment for me, seeing that exact causation that you just outlined. That if the oikos is the realm of the woman and church was held in the household, it was in the realm of women. And you even say in the book that early Christianity almost had a reputation of being a women’s movement, which was mind-blowing for me that it had that association early on.

KT: Yeah. One quick comment. Celsus was a famous intellectual and very anti-Christian, and he felt so strongly about it that he wrote a treatise on it. And in his treatise, he said, “These Christians, what are they? You go to one of their meetings, and what it is, it’s women and peasants. That’s all there is.”

AA: Hmm, so interesting.

KT: Yeah. So he dismissed it. He could dismiss it that way.

AA: And this led also to what you flesh out and illustrate as where men and women had lots of different roles in early Christianity, and kind of to the point of your book and the title itself, is that women occupied positions of authority in the early Christian church and roles that we would never associate with women, right? Because we read the Bible and we read all of these positions like the bishops and pastors and prophets and teachers and evangelists, and at least when I hear all of those words, I picture men, men, men, men, men. Tell us why that’s not accurate, Karen.

KT: You can see that in the household, a woman is a disciplinarian, a woman is a teacher, a woman is an organizer. And so one of the places that was fascinating for me to get information from, we already knew that widows were a separate group. They were provided for by the community, that’s the social welfare part of early Christianity and we think of it in those terms, but the widows were also an order. They were seen as part of the clergy, especially in the texts of Eastern Christianity. And so you have the widows evangelizing, doing instruction for baptism, doing discipline, along with teaching and enjoying significant authority. Doing visitations, doing healing, and that went with their social role as widows. That had a certain power in it. It wasn’t just someone who was receiving welfare, they were recognized. And there are a couple of texts that show them at the altar with the clergy.

AA: Wow. These are things I never learned in Sunday school. Really quickly, let’s shift gears and talk about Paul, because Paul is obviously controversial, and there are passages in the New Testament from Paul that feel pretty hurtful for women. So can you tell us what he wrote and then complicate that narrative a little bit by giving us some evidence that Paul did respect women as leaders during his era?

Widows were also an order. They were seen as part of the clergy

KT: He’s such a fascinating figure in every way. He was crucial in the formation of a Christianity that was defining itself as distinct from Judaism. So he was very influential and he was very daring and courageous and zealous as he described himself. So it was a period of evangelism, you know, Christianity was spreading like wildfire through the region and carried by all kinds of people, women and men, and they were supportive of each other. They often met in prison in areas where Christians were being persecuted. They kept in touch, they formed a network with each other and encouraged each other and compared notes. I mean, it’s a missionary culture. If you’ve been exposed to one, you know what that is, and you can get the sense of the excitement and the adventure involved. So Paul had many associations, and the part that was most exciting to me was the work that Bernadette Bruton had done. In the last chapter of Romans Paul greets all kinds of friends and fellow missionaries from everywhere. But the ones that were in Rome were the ones that he was addressing himself to, greet this person, greet that person, so these are Romans that he met somewhere on the evangelistic trail. And there are, as I recall, 21 of them, and a full third are women. And I used that because I thought it makes kind of a rough sense that probably in terms of leadership it’s at least one-third women in these roles. So that became, for me, a larger framework.

And then Paul’s writings to the churches are very specific to that particular community and to whatever was undermining the unity of the community. So you had communities that were debating gender, and he intervenes in those in different ways. So you have a lot of commentary in that sense of Paul on gender as it operates within a community and a particular community that was struggling. But that has to be read against the backdrop of how many of his colleagues were women and how and those relationships are warm, admiring, women feel supported. So who Paul was on the road I think is more supportive than the Paul that has been created by church leaders and pastors who are opposed to women’s leadership. And so they’ve made a canon, in a way, of restrictions on women’s roles that they’ve drawn from those Pauline letters. That process of sifting and shifting and changing is particularly visible in terms of what happens with the copyists.

And so my favorite story is one of the persons that Paul greets in Rome, is Junia and Andronicus. And Junia, he calls them “foremost among the apostles.” So apostles of the apostles. And that continued in that passage for several centuries, but somewhere around the 11th or 12th century it became Junius and Andronicus. So there was a sex change operation that took place with the pen of a copyist who said, “Oh, that can’t be. That must be a mistake. We’ll correct it.” And Bernadette Bruton, in her scholarship, documented that there is no Junius in any Roman text.

AA: But there is a Junia.

KT: There is a Junia.

AA: Wow.

KT: And she established that. That’s an example of several things. One is what feminist scholarship has provided. Two, it sheds light on the process of change that takes place through the simple practice of copyists. Because these texts are copied by hand until you get to the printing press. And there are changes in everything, not just issues on gender, all kinds of theological changes that take place and so on. So these are things that the historian has to account for, or can account for. It’s always more complex when you start digging.

AA: Yeah. And I can imagine that each individual person has this document in their hands and it would be so tempting. Sometimes, I’m sure, it was completely unintentional and not conscious at all. They just bring their own lens of assumptions and experience, and they’ll have that masculine lens on and bring it to their work unconsciously. And sometimes there may have even been deliberate changes made to alter it just a touch. So the next step in the chronology would be to return to that piece that you talked about before. You have the house churches, you have almost some egalitarian structures within earlier Christianity, because the house is the domain of women and Christianity is in the house, and so women are evangelizing along with men. And then you brought up that with Constantine things started to change. They build a basilica and it becomes more Roman. Is that correct? Maybe we can talk about the transition to where the church started to become more male dominated.

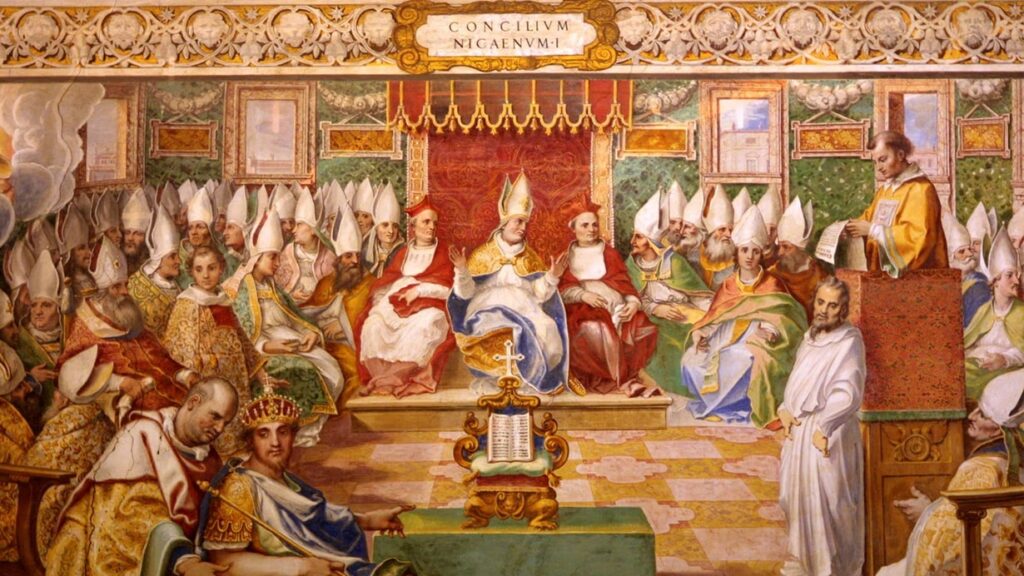

KT: Yeah. And after the question of women’s leadership, that was the question that occupied me the most when I was asking, what’s the process? How do you reconstruct the changes that took place? And we can start again with Constantine. Constantine made Christianity the state religion. And Constantine did that by getting involved in a theological controversy and inviting all the bishops from all over the Mediterranean and sending them all-expenses-paid invitations to Nicaea for them and their entourage. It was the first time an emperor had ever done that and it was a tremendous honor to the Christian churches and to the bishops. That’s a big change point, so I’m going to go back one step and say, why did Constantine do that? What made Christianity such an attractive ally in running the empire? My answer to that question, as I began exploring it, is that what was happening was the house churches were evolving in the first century and the second century, and by the second century and the beginning of the third century, you have the houses of the church that are just for the church alone. And you have a process of centralization taking place at the same time, so that there is one leader in a house church, the leader of the house church is the patron. When you have multiple house churches in a city, now you’re going to get some centralization of leadership. So there’s one influential church group, and one influential leader, and so you get the development of what is called the monarchical episcopate. So the bishop, who had once been an apostle or a teacher or a prophet, and that had been the source of authority, now develops a judicial power, and there are actually bishops’ courts. It’s on Monday. So Christians are not to not go into the secular courts, they’re to bring grievances together. And so you have a monarchical bishop who holds court and gives justice. So that’s a different kind of discipline than you had when it’s a group disciplining.

AA: Can I ask a question really quickly? When you’re talking about each little home church headed by the patron, could that have been the woman patron or a man patron or either one?

KT: Sure. We know that because we have calls addressing women and the church that’s in your house. So we know that.

AA: But then when it changed to the ecclesiastical bishop, and they’re over a court, could women do that role or is that maybe one of the tipping points where the change is?

KT: That’s a very good question. We have been looking at textual evidence, right? We’ve been looking at evidence that’s written down and copied and transferred, knowledge transferred that way. There’s another form of evidence that we already have talked about, which is architecture. There’s material evidence as well. And so there are inscriptions, dedicatory inscriptions, where something in the church has been dedicated, a gift to the church by so-and-so. And there are epitaphs, which are the funerary inscriptions. This is the husband of this person, or wife of this person, and so on. So in both of those contexts, they were done in the Roman world with the titles that they held, with the offices that they held. And so there has been growing evidence, now that we’re paying attention to it, of women officeholders that we can verify through inscriptions and epitaphs. And there are women bishops.

AA: Wow, that’s so cool.

KT: They’re women bishops, women presbyters, women priests, and women deacons.

AA: Well that’s what I was going to say, actually. I think it’s worth pausing here because as we were talking through this I thought, I need to go back and ask this question really explicitly. And maybe this is me coming at this from a Mormon context where women still are not ordained and there have been controversies that have come and gone, but the male leaders of the church are sticking to prohibiting women’s ordination. So the title of your book is just so evocative: When Women Were Priests. I want to pause here and emphasize that, that you’re saying that all of these positions of leadership were held by women, including priesthood, including maybe performing saving ordinances, including overseeing councils, including standing at the front and saying, “I’m in charge.” It’s incredible.

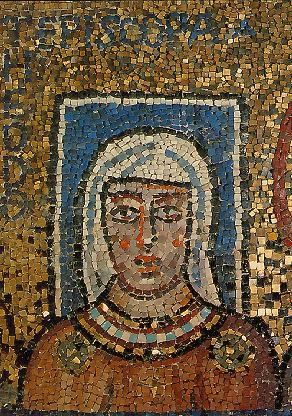

KT: There are no questions. And I’ll tell you this story, again, because it just has so many pieces in it. My editor chose the title When Women Were Priests. And in the book, I describe a basilica that I had visited where there was a mosaic of four women. One of the women had a square halo, meaning that she was still alive, and the others were saints. They had died. And the inscription around the woman was Episcopa Theodora, or “Bishop Theodora”. And so he was fascinated by that and said we should make that the cover of the book. And so he had his assistant, who was fortunately Italian, call the church and say that we have a book that we’re going to publish and we’d like to put this picture from your church on the cover and we would like to have permission. And so the priest said, “Well, what’s the book about?” And the smart, fast-thinking Italian girl said, “It’s about holy women, Father.” And he said, “Fine, that’s great.” So it got published.

So fast-forward. I’m thinking I won’t be very welcome when I go back into that church. Because a few years later, I do get back to Rome and I go into the church and a priest comes up to me. He sees I’m looking around and says, “Come let me show you something. Here is a picture that an American scholar thinks is a woman bishop, and women have been coming steadily to see it, and you probably want to see it too.” So I was thinking that what happened is that there’s no anger over the gender stuff because this little tiny church is getting attention and that’s good. Hooray, hooray. The story’s not over. So that was really fun. I come back another couple years later, and the A on bishop has been scratched. It’s a glass mosaic and it’s been scratched out, erased. And two years after that I came back, and the whole mosaic, that piece of it, had been redone. You couldn’t see anything, and it said nothing. The record is gone of Episcopa Theodora.

AA: What year would that have been?

KT: Gosh, when was the book published? The book was published in–

AA: ‘95 or so?

KT: Yeah, ‘95.

AA: Oh my goodness.

KT: So it began around 2000. But there’s the whole story.

AA: They’re still doing that?

KT: Yeah!

AA: Whoa. The iconoclasty and taking out the historical record in the year 2000. That’s insane.

KT: Yeah. Anyway, that story tells so many different things.

AA: Oh, that’s amazing. That’s tragic. Unbelievable.

KT: It is.

AA: Do you know how that happened? I wonder if the leader of that local church chose to do that himself or if he was ordered to do it by a higher up?

KT: I’m sure it was a higher up. Because he was in charge of the little church.

AA: Right, right.

KT: People came, it was getting a reputation. But it was higher up.

AA: Oh my goodness. Well, that’s amazing. That’s a great bridge to get back to this story, which was that at one point women were operating as leaders in the church and then at some point, it’s kind of like my introduction, like, what the heck happened? What happened to create– I guess, in this last portion of our conversation, we’ll talk about how the Church became so masculinized. And so that takes us back to the Council of Nicaea, right, Karen?

KT: It takes us back before that, because the question I’ve asked about Nicaea is, why was that so beneficial to Constantine? Why did he do it?

AA: Right, okay.

KT: What were the politics? What’s happening in the third century is that there are more and more members of the upper class who are converting, and they are invited to be bishops because they have connections, they have wealth, they’re patrons. It’s perfect. And they have served in public office. They’re now in the class of people who take city administrative offices or administrative offices in the empire. So they bring with them the culture of public life and the values and the gender system that underlies it. And so you begin to get conflict over women in leadership because of this model. And then as you get closer to the 4th century and they become more and more powerful, then they really do represent a block of power. If you have the bishop of a large city in your patronage, that person, that individual can command votes, authority, influence on your behalf. So it’s a smart move. The success of Christianity made it attractive for politicians like the emperor. And so you get a merger, really, between the traditions that Jesus gave and the forms of leadership that evolved first in the house churches and then more and more from public space. And that’s why there’s greater and greater pressure on women in leadership roles. And by the time you get to the sixth century, there are debates over whether women can sing in the choir. Whether women’s voices can be heard. So there’s a trajectory that’s followed, and there’s resistance all along the way as well.

AA: Well, I think this argument is very much alive even in the modern Christian Church. We still have a debate between whether women are allowed to have authority, whether they can be ordained in certain denominations, like we talked about earlier, or even whether there should be gender equity. And I know one way of framing this is with egalitarianism versus complementarianism, which is an argument that persists today. Can you tell us a little bit about egalitarianism versus complementarianism?

KT: Yeah. My perspective is the perspective of an academic and someone who is very interested in the processes of social change. So, as I told you, once we had a chair in Mormon studies, and we also had the PhD in women’s studies and religion, I started getting Mormon feminists coming to the program for their education. So it was really fascinating to watch them, because what they’re doing, they fully understand the character of patriarchy and the way that it operates within their own world. And they have made a fundamental decision, and some of them didn’t do this but most of them did. They wanted to stay within their tradition. They felt like the challenges of feminism could mean that if I followed that, I would have to give up my tradition. And I was particularly interested in the ones who didn’t, and most of them wanted to stay within the tradition. So then they began the process of, “Okay, how can we change? Where can we change? What are the pressure points?” So I feel like we’re in good hands because of those women. And I watched them in their writing, and one of the ways they’ve created to expand, this is my interpretation, to expand the roles for women is to evolve this theological concept of complementarianism, so that it’s not a frontal attack on patriarchy but it’s a strategy for empowering women within it and expanding their roles, giving them a new voice.

For example, one of my students, a recent PhD, finished a dissertation on what was happening in the blogosphere, and it’s phenomenal. I mean, these women who are blogging, and in a way you’re doing things very similarly, they’re doing prophetic work. They’re doing theological work. They’re leaders, they have followers, they have people who listen to them and are guided by what they say. These women have immense authority and they found a way to create it. No one’s baptized them. There’s no ritual by which they have been given this power, but they have created spaces. That’s what this dissertation was saying. They have created spaces for women. They’ve created a voice for themselves and they’ve created a voice for women. So that’s what I see happening in that process. There’s a lot of pressure building, and I don’t think that’s the last station. I think that there will be evolution beyond complementarianism, but I think that’s what it does.

These women have immense authority and they found a way to create it. No one’s baptized them. There’s no ritual by which they have been given this power, but they have created spaces.

AA: Well, it’s really interesting to hear your take on Mormon feminism from the outside, and that actually was a really beautiful way to frame that. I hadn’t thought of that, you know, women not being ordained necessarily but finding a different avenue with which to have to exercise maybe even more authority, for sure more authority, than if they had been ordained to a traditional role as a bishop within the traditional structure. That’s interesting. If we have time really quickly, could I ask you about egalitarianism versus complementarianism in the Protestant world? I’m seeing a lot of people debating it right now, that there’s evidence in the Bible that because of this evidence that you just talked about, that women were priests before, that women had authority before, so Christianity is inherently egalitarian. Jesus established an egalitarian ethos and that women had authority before, versus complementarianism. I’m seeing that argument a lot online still.

KT: Yeah, that’s right. And that’s big among Evangelical Christians. And let me put it this way. When we first started this work on women’s ordination back in the eighties, I thought we were looking at 200 years. We’re in it for the long haul. So I thought that there was so much change within a short period of time, and it’s everywhere. So, for example, I also work with the Eastern Orthodox churches, and some of them are now close to ordaining women deacons.

AA: Oh, wow.

KT: Because that’s clearly an office that women helped, and it matches tradition. So it’s a return to tradition and we’ve been failing, so you can see that kind of expansion. And then of course in the Catholic Church, what you can see is really, I mean, the amount of visibility that women have in the Church is just stunning in comparison to what it was thirty or forty years ago at every level. And the Church is shorthanded. There are not enough priests, so they’re going to have to do something about that. So that’s really powering a lot of the change. And then you have moralist German scholarship that’s been going on for quite a while on the canons of ordination and of women being ordained as bishops. And within that group, this is in Germany, evidently during World War II, when so many of the men were imprisoned or died, it was done secretly, but there was a group of women who were ordained as priests so that the sacraments could continue because it was essential for the survival of the community. And so one or two of those bishops who were part of that ordination of women had the lineage and were willing to ordain women. So a new kind of movement of ordaining Catholic women to the priesthood has emerged.

I’ve been to several of these ordinations, and they are done often on a river because that makes jurisdiction ambiguous. And there are now churches that are calling these women. So I know of women here in our area who have been through the ordination process, have been called by a Catholic church, and are functioning as priests. This is within the Catholic Church. That’s how it’s working there. Now they get excommunicated.

AA: I was gonna say…

KT: Yeah, exactly. But it’s still going on and it’s spreading. So that’s a kind of underground movement of women’s ordination.

AA: Interesting. Well, that brings us to the end of our discussion, Karen. This was so fascinating. I’m so grateful for your book, for your scholarship, for all the work that you’ve done in the world. Do you have any final thoughts as we wrap up?

KT: Well, I have a final thought, which is that I think what you’re doing is amazing. I see the model that you’ve chosen of a podcast, your use of technology that way, the social model that you’ve used as a discussion conversation that makes everyone feel comfortable and connected is fantastic. I feel like the way you’ve organized it around themes and how much you’ve picked up the international is just awesome! I mean, you’re an example of what I’m talking about. I’m quite encouraged. I am not discouraged.

AA: Oh, wow. Well, for listeners, for the record, I did not know she was going to say that one! That’s so kind of you, Karen. Thank you. This has been an absolute honor and a delight to meet you and to benefit from your work. Thanks again so much for everything you’ve done and for being here for the conversation today.

KT: My pleasure, indeed.

You are always quarreling with the women.

Why don’t you just listen to her, and we will go and do as she has said?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!