“there should be a hundred words in our language for all the ways a Black boy can lie awake at night.”

Amy is joined by Stacey Harkey to discuss How We Fight for Our Lives by Saeed Jones and focus on the experience of being Black and queer in America.

Our Guest

Stacey Harkey

Born in Dallas, Texas, Stacey Harkey considers himself to be a Southerner to the core. After graduating with a degree in public relations from Brigham Young University, he was a writer and actor for the sketch comedy TV show, Studio C. He is currently a personal trainer, a corporate DEI consultant, and owns a media company called JK Studios. Stacey is a firm believer in the power of an embarrassing moment, a burnt meal, and an extremely difficult challenge.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: This month in honor of Black History Month in the United States, we’re staying right here on American soil and focusing on the experience of Black Americans. And today we’ll be talking about the Black queer experience. We’ll spend most of our time in the realm of personal experience, both from the memoir, How We Fight for Our Lives by Saeed Jones, and from our guest today, the incredible Stacey Harkey. Welcome, Stacey!

Stacey Harkey: Howdy, howdy!

AA: So great to have you here. And I have to say really quick, as a disclaimer, Stacey and I recorded this episode last month when I was getting over being really sick so my voice was really low. And we recorded the whole conversation, it was awesome, and then I went to edit it and something happened with the microphone and I lost like a quarter of the episode. So we are re-recording today.

SH: I think I actually sound a little sicker today, so…

AA: If you notice a little change in our voices, that’s why. So I just wanted to give that disclaimer. Okay. For listeners who don’t know who Stacey Harkey is, I’ll read a little professional bio for you, Stacey, and then you can introduce yourself personally in a second.

Born in Dallas, Texas, Stacey Harkey considers himself to be a Southerner to the core. After graduating with a degree in public relations from Brigham Young University, he was a writer and actor for the sketch comedy TV show, Studio C. He is currently a personal trainer, a corporate DEI consultant, and owns a media company called JK Studios. Stacey is a firm believer in the power of an embarrassing moment, a burnt meal, and an extremely difficult challenge.

That’s awesome, Stacey. I’d love it if you could just introduce us to you a little bit more, where you’re from and some of the things that make you you.

Stacey: Of course. So I am from Dallas, Texas, I actually grew up from a place not too far from where Saeed grew up, which I absolutely loved, and we’ll jump into that a little bit later. I am just a big old extroverted nerd. I just wanna get in people’s brains and see their feelings and be challenged in the process. I don’t know, that’s me in a nutshell. I just love people and I love the rawness that comes from unfiltered experiences, which we’ll see a lot of in this book and we’ll talk a lot about. And so this felt like a very good choice for me to be a part of this podcast. I’m excited.

AA: Yeah, it’s been a really neat experience for me. Because we each read the book, Stacey and I read this book, How We Fight For Our Lives, and then we texted each other what we liked as we were reading it. And I was learning so much through the book, but then being able to converse with you was a really neat, profound experience for me. And so I’m really grateful for that and the experience that we had even in preparing for the podcast, too. It’s actually quite a serious book, but I thought it was really heartwarming sometimes too, and life-affirming and beautiful, even though hard to read sometimes. But let’s start by learning a little bit about the author, Saeed Jones. Stacey, could you introduce Saeed?

SH: I’d love to. Saeed Jones was born in 1985 in Memphis, Tennessee. He was raised as the only child of a single mother in Louisville, Texas, and attended college at Western Kentucky University, then earned an MFA in creative writing at Rutgers University-Newark. His debut poetry collection, Prelude to Bruise, was named a 2014 finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry. His second book, a memoir, How We Fight For Our Lives, won the Kirkus Prize for non-fiction in 2019, as well as ecstatic reviews from every publication imaginable. And I’m just gonna say, I absolutely loved this book. I used the colloquial slang term, I was shooketh. I think I might have texted you that a couple times. I was just shooketh by not only how brilliant Saeed is, but how much I could relate. I was like, he’s writing experiences that I’ve had directly. We will warn listeners right now that there are very explicit sexual scenes and some of it’s kind of hard to read. It isn’t gratuitous sexuality for the sake of sensationalism, it’s important in understanding his experience in particular, and broader social patterns in general. He tells the truth in all its detail, but if you’re not used to that, as some of us aren’t, it can feel kind of raunchy. But yeah, that’s my take on the book. It was just beautiful, and relevant, and ugly, but in the sense of like, it’s real.

AA: So, we’re gonna take turns sharing important passages from the book. And Stacey, I’d love it if you could share your thoughts and experiences as it brings up different issues. The first topic that we wanted to talk about, that’s a major theme in the book, is racism. And there’s a passage that we wanted to highlight that talks about the murder of a Black man that really impacted Saeed, I think he saw it on the news. So Stacey, if you could read that passage and then just talk about it.

SH: Yeah. “After a long day of work, James Byrd Jr., a Black man, accepted a ride home from three white men. Three white supremacists, he realized a moment too late. They beat him, chained him to the back of their truck, and dragged him for more than a mile down a desolate country road. Jasper, where Byrd lived and died, is just a four hour drive from the living room where my mother and I sat that evening. I was a Black boy in America, curled fetal in his twin bed, ears ringing with the rattle of chains. Just as some cultures have a hundred words for snow, there should be a hundred words in our language for all the ways a Black boy can lie awake at night.”

Man, just like he said, there should be a hundred words in our language for all the ways a Black boy can lie awake at night. I remember begging, praying to God, begging him to fix me for being gay. To fix my life because of poverty, or loneliness, or just being treated differently because of my skin. Truly I could relate to that. And it brought those feelings back. Stung.

AA: It was devastating to read that when I read it, too. And one thing that really struck me was that image of him curled fetal, lying awake. And when it says “ears ringing with the rattle of chains,” just the legacy. Yeah, so poetic, but also that concept of intergenerational trauma and the legacy of slavery still for this kid, it’s still there. That’s what’s ringing in his head, is ancestors and what happened. That doesn’t go away just because it’s not happening anymore. And on this topic too, once I started studying history and I started drawing timelines, it really struck me how recent it was. There’s no way for the practice of enslavement to have worked itself out and gone away, especially because it was followed by Jim Crow and segregation and ongoing racism, of course, but just the connection to slavery. It’s still there.

SH: Oh, for sure. I actually spoke shortly after George Floyd was murdered. I feel like we saw this different America, and it was actually in some ways very heartening to see everyone rally behind that, for everyone to see that and be so disgusted and to feel the weight of knowing that happened in our backyard, you know, in our country. And I remember talking to some people, I spoke at a thing and I just wanted people to understand that while people were rallying for the first time and awake to this thing, especially a lot of white people, I wanted them to know that while this was a new battle for them, for some of us, this was like a family heirloom we’d inherited. This has been a constant battle that not only we fought, but our parents have fought, and our grandparents have fought. Do you remember the exhaustion of being like, can we ever do anything? The frustration with things not being able to change, that’s generationally been inherited. And it’s so oppressive and frustrating. And oppressive in the sense of emotionally, creatively, it’s like this cloud, this smog that hangs over all the time. And Saeed kind of talked about this in the aspect of belonging and how tough it was being Black and gay and a nerd. And I could relate to that so much. When you think about, okay, what do white people like? You might have a hard time because you’re like, “oh, well there’s so many different types of white people.” I mean from sports to trivia, there’s just such a range. And I don’t feel like Black people are often afforded that, even within our own community sometimes.

And so Saeed talks about how just because he was gay, Black, and a nerd, he literally had nowhere to belong. Because if you don’t look like a stereotype to people, they question your very Blackness, which is so frustrating. You know what I mean? It’s like, “oh, you don’t have gold teeth and baggy pants and love hip hop? You must not be Black.” And it’s so frustrating when your very identity that you’re fighting to have pride in is stripped away from you if you don’t satisfy the very demands of whatever community or groups you’re trying to associate with. And I totally relate to that. I mean, over time, identity for me has been shaped by those experiences because I felt like I was never quite welcome. But I embraced these identities. And so my definition now is that like… What does it mean to be Black? Whatever I do is a Black thing, because I am Black and I define the identity and not the other way. What is a gay thing? It’s whatever I’m doing. If I’m arm wrestling someone, it’s a gay thing because I am gay. You know what I mean? I define my identity and the box doesn’t define me.

AA: Okay, so the second topic that we wanted to talk about is homophobia, and obviously racism and homophobia are woven through the whole book. But there are a couple of quotes that we wanted to share and then I wanted to hear your thoughts on these, Stacey. Can you read that second quote that we identified?

SH: “You never really forget your first. Where and when and who you were. 16 years old at the football game. 26 outside the bar. 12 on the playground. Or who they were, all the boys with mouths shaped like knife wounds. The men in the scuffed boots, the ones who look like your father or brother. You never forget when the word was first hurled at you or whether a fist or a baseball bat came swinging right behind it. Whether it was whispered, spat, or graffitied. You never forget your first ‘faggot.’ Because the memory in its way makes you. It becomes a spine for the body of anxieties and insecurities that will follow. Something to hang all that meat on. Before you were just scrawny. Now you’re scrawny because you’re a faggot. Before you were just bookish. Now you’re bookish because you’re a faggot. Soon, bullies won’t even have to say the word. Nor will friends, as they start to sit at different lunch tables, without explanation, there will already be a voice in your head whispering ‘faggot’ for them.”

if you don’t look like a stereotype to people, they question your very Blackness

Whoo, very intense. And honestly every time I read a passage I would dive into my own experiences. And I don’t ever remember being called a faggot. That’s an interesting word too, because in the gay community, I don’t know how common it is, that’s a word that’s being reclaimed. Like the term queer, which had a negative connotation and now we’re reclaiming it. We could call it the f-slur if you want. I’m unsure how to refer to it right now, actually. But anyways, that word is getting reclaimed. I think about times though, where I immediately was taken back to where people called me veiled names, right? Like I was called things like ‘sugar foot’ or ‘sugar tank’ or ‘Philly boy’. So I really resonate with that, because those things stick. And it’s true, it’s like your whole identity now. Like, of course you like that musical, you got a little sugar in your tank or something. You can’t just exist. There’s always some qualifier about it. And he talks about in the beginning, I don’t know if you remember this, he talks about – of course you remember, you have a great memory – watching his mom celebrate Prince. He’s singing in this high pitched voice, wearing makeup, all these like gaudy colors and sparkles. And she is just swooning. And I was like, yeah, my mom loved Prince and Michael Jackson! These very, almost what we would call feminine men who were just icons. And it’s really interesting and unfair. I remember being scolded as a child, I would wear my sister’s shirt, or a skirt or something, or put it on my head and dance. And I remember being chewed out for that, and in like the same space that like our, you know, lord and savior Prince is dancing around gloriously. And I’m like, what? It feels like an interesting catch-22. But it all comes down to sexuality, right? Like how it’s presented. Prince was seen as…like women wanted him. He was seen as a very sexual being, very straight. And while my actions were contextualized in a very queer sense, or very not masculine sense.

AA: One of the lines from that passage you read that was really interesting to me and really heartbreaking, is the last one where he talks about how once you’re called those slurs, bullies don’t even have to use the word anymore, it gets in your head. And that internalized homophobia starts to take root, which is the same as all of those awful labels and oppressive labels, I guess like internalized racism, internalized misogyny, and we start to bully ourselves with those voices. Do you have anything that you wanted to say about that, Stacey?

SH: Yeah, actually just super spot on. I remember at a young age knowing that certain behaviors were wrong and bad. And this is from a young age until like college, well, adulthood when I came out. But so much mental energy goes into self-policing or self-analyzing. Like, I would check my fingernails a certain way to ensure that people didn’t think I was gay. If I stepped in something, I consciously would be like, don’t look at your shoe that way, look at it a different way. Walk a certain way, talk a certain way. So much energy goes into trying to hide that as a kid. Or an adult, especially in spaces that have made that clear or even implied that that’s not welcome.

And I think you see it with different cultures, too, especially being Black. There was a big debate going around online not too long ago with women wearing bonnets, which are generally worn to protect their hair at night, out in public. And I think the only scorn came around because it was perceived as a very Black thing in white spaces. So it’s like policing ourselves that internalized homophobia, racism.

AA: Awful. Another passage that I wanted to ask you about, because I was so curious about this, it brought some things up that I’d never thought of before. The author talks about in high school that they were watching the play The Laramie Project. And The Laramie Project is a series of monologues that are based on interviews that were done in the weeks following the murder of Matthew Shepherd, who was a gay 21-year-old man in Laramie, Wyoming. Jones says that the hate crime murders of James Byrd and Matthew Shephard – James Byrd being the Black man who was killed, and Matthew Shephard being white but gay, and he was killed for being gay – that these murders started to swirl and converge until two truths collided. And then he writes, “Being Black can get you killed. Being gay can get you killed. Being a Black gay boy is a death wish. And one day, if you’re lucky, your life and death will become some artist’s new project.” I don’t know if you have a comment.

SH: It’s just so sad. The only way this attention can be brought to this is in someone’s death. Why did we have to wait until George Floyd was choked out to all of a sudden feel like this is an issue, right? And I’ve thought about that before, where I’m like, “I’m gonna leave and become another statistic.” And then we’re gonna be interviewing my friends who were like, “I guess he could have done that.” I don’t know. I’ve been scared about that. And I don’t know if I’ve grown up feeling like I could be killed for being gay, but I knew that I would lose relationships and I knew that I would lose connections and opportunities if I was perceived as gay. And sure enough that happened when I came out. So it kind of makes sense. It does feel kind of like, a death wish might be a little strong, but it does feel like it cuts off a lot of opportunities for you.

AA: Another part of this same scene in the book when they’re watching The Laramie Project, I wanna ask you about this because this is the part that I had never thought of before. It’s a really cool scene because I thought, this is great, the high school is having them watch The Laramie Project. That’s awesome. Yay! They’re doing some actual anti-homophobia. But then it was so interesting to read about the girls’ and boys’ different reactions as they watched this play. He talks about how the boys are all basically masculinity signaling to each other, which isn’t surprising, I guess. But then it was so interesting because he says,

“Within just a few minutes, some of the girls in my row were sobbing. A few held one another’s hands. The monologues were heart-shattering. I envied the girls who felt comfortable enough to cry. How easily they breathed. All the boys near me looked indifferent. I would think later that maybe some of them were only pretending to be indifferent. Maybe some could only sit comfortably, whisper ironically, laugh audibly with total effort. For me, it took all I had to sit still and silent.”

I mean, obviously what you just described, Stacey, right? He’s not out yet, and so he’s really monitoring every little micro-movement, is what I’m gathering. And then, as a straight person and as a girl, as a white girl, I’m the girl sobbing basically in this scene. And you and I talked about empathy, and it was really interesting for me too to read the next part. Because I think at first he’s kind of touched that the girls are crying because he’s like, oh they care. But he can’t show that he cares because then maybe he’ll out himself. But he writes,

“The girl sitting right in front of me let her head drop to her chest, as if felled. She shook her head back and forth, crying softly. It repulsed me then, her freedom. I tried to ignore a second girl now sobbing right next to me. I tuned out the words he spoke for fear that if I let myself pay attention, I would start crying too. I would start sobbing and not be able to stop.”

So I sat with that and I thought, again, I really thought about how many times I have wept about the struggles of people that I care about that aren’t my own. And it hit me in a different way as a privilege that I can cry about it openly. And also that I can cry, but then I have the privilege of walking away and it’s not my lived reality. I don’t know, Stacey, is it self-indulgent almost to cry about it? I don’t feel like these girls were being performative or anything, I feel like it was genuine. I don’t know. Help me process this part.

SH: I don’t know if I have the right answer, but I have my opinion and it’s that those girls weren’t a problem. They weren’t feeding into some terrible system by crying and feeling. They were just as much victims to homophobia as he was, in the sense of how they interact with it or the place it has in their community. Just like the straight boys who were maybe concerned to show emotion because people would think they were gay. We’re all victims of this system and it interacts and affects us differently. Like, Saeed experienced it in such a pain, and maybe the girls experienced it in hearing these horrible stories and they didn’t experience the same pain that Saeed did, but I think everyone’s victims in this. I don’t see a lot of value that comes from being like, you can’t feel because I have a right to feel more. Right? I just don’t see what benefit comes from that. I don’t know, what are your thoughts?

AA: I guess my thought is to make sure as I am examining my own reactions, to try to make sure that I wouldn’t then center myself and my own emotional response above someone whose life really was impacted more than mine. You know what I mean? Just to make sure that I’m not taking away the centrality and the real acute issue that it is for people that it does affect. It was a really good exercise for me to make sure, like, where’s that coming from? And how to be supportive and not self-indulgent in our own emotional reactions, I guess. Anyway, such an interesting scene for me, and also to be aware of how that could impact somebody else.

SH: That’s a great takeaway, right? I think so. I think it’s a great takeaway of like, feel your feels, but where’s the focus of that? Or where’s that centralizing around? I think that’s a really great way to look at that. Love it. A couple more sections where Saeed talks about living within a homophobic world, Saeed had planned to come out in college, but then on his first day of school, decided not to. He says,

“It shouldn’t have been that easy to unbecome myself. The lies and omission started to roll off my tongue and I began introducing a person who I wasn’t exactly, while smiling.” And then later he’s talking to his mom and he slips in a reference to a guy he dated. Then he sees that she doesn’t want him to go there, and he says, “She was staring at me wide-eyed, almost pleadingly, as if I’d led someone afraid of heights to the edge of a rusting bridge. And then I did exactly what I thought all people who love each other do. I changed the subject. I changed myself. I erased everything I had just said. I erased myself so I could be her son again.” Heartbreaking. Isn’t that the saddest? And it’s so true! The way I worked to become– and in reference, I don’t think about that with my Blackness. The difference between being Black and queer for me is, not only I can just hide being queer – I can just not present a certain way or something, or not kiss a boy in public or whatever people use to tell – but also I have a family system, my family’s all Black too. And so when it comes to prepping you to handle the world, you get generational information. My mom and dad can help prep me and teach me about what it means to be Black and how to navigate in a better way. That is not the case with being queer. I didn’t have someone who could sit me down and say, “hey, this is how you can navigate this world.” Or, I didn’t have someone sit me down like I did as a kid and say, the world will tell you that you’re wrong or that you’re bad for something you can’t control. And you’ve got to say, you know what? You’ve got to realize that we’re great. Black is beautiful. There is Black excellence. Like the beauty of Black History Month to show us that Black people invented things too, and built this country up, and did brave things. We just did not have that for queerness at all, for the queer community.

the beauty of Black History Month to show us that Black people invented things too, and built this country up, and did brave things…we just did not have that for queerness at all

So for me it was like navigating that by myself or trying to find ways to hide or stifle this thing that I knew was wrong. I knew at the time that being gay is wrong and I had to do everything to change myself or erase it. And it does remind me of the relationship he had with his grandmother, who was a very religious figure in his life. His mom was, I believe, Buddhist and had a very interesting relationship with religion and didn’t really talk about sexuality in that context. But his grandma did, and she would say, “hey, we don’t act this way.” She would drag him to church. And once at church, his grandmother, almost in cahoots with the pastor, prayed that her daughter would learn the ways of Christianity and have hard times to help her realize it. She kind of cursed her. It wasn’t like “I pray that good things happen,” it was like “I pray that bad things happen.” And it made me think about the role religion has played in my life as a queer person. And religion is often used in a nefarious way. For me in my life, when it comes to my identity, religion was the reason to change. Intense punishment was barely being held at bay. If I entertained any thoughts at all, religion was used to control me and cajole me, or to call curses down on me. And it kind of blew my mind that even my mom, who is very religious, talked about like, “I hope you have experiences that help you learn where to go.” You are not wishing for the best, you’re hoping I have a hard time. And like Saeed talks about this in the book, where it just played a very oppressive, life-threatening, family-dividing role. It almost feels like we would talk about black magic or something, ironically.

AA: Yeah, that part was so awful. So, so awful to hear his grandma curse her own daughter so that they could repent. Oh, so bad. And I don’t think the relationship really ever recovered after that. Thanks for sharing that part, too, where we get inside his head when he’s in that interaction with his mom. Because his mom actually is so loving and supportive, and you can correct me if I’m not interpreting this correctly, but I just feel like maybe he could sense that she probably would think it was easier if he wasn’t gay, and she didn’t necessarily want that for him. And so where he says, “I changed myself, I erased everything I had just said, I erased myself so I could be her son again.” It just broke my heart, but I’m so grateful that you shared it. For people who are straight who are listening, if we have people who we think might be queer and they might be needing to come out, just be aware. And actually, even if we’re not in a scenario where we think someone might be queer, but just to realize that people around us are, all the time, that we don’t realize. And I’ve said on other episodes, listeners, if you are religious and you’re teaching a Sunday school class to youth, somebody in your class is queer. And they’re the ones that are sitting there like, “do I need to erase myself in order for this adult to love me? Do I need to erase myself for my grandma, for my aunt, for my friend’s mom or dad to love me?” And it’s just so hard because we do live in this patriarchal, heteronormative society where we do assume that everybody we interact with is heterosexual. But to try to remember that that’s not the case, and that we can be accidentally stifling people all the time, and we wanna be a safe person for people to be who they authentically are around us. So we don’t make anyone feel like they have to erase themselves in order to be loved by us.

SH: I think you’re spot on, and I think that is an interesting thing that Saeed really explored, is how loving his mom was. And even her friends, very supportive, took him to his first drag show and gay bar, and they were lifelines for him, these people his mom loved and associated with. But one thing that I love about this experience is that’s often how– at least in my experience, I knew coming out that my parents would love me still. They did a good job of expressing that. I didn’t know if they would like me or want to be around me. And the thing is, when it’s attached to this concern or this fear you have, you are hyper-vigilant. Marking someone who is safe is not just, “oh, they are nice to me.” You have to actively mark yourself as a safe place for someone who is trying to figure out if this thing that is gonna lead to their separation from society, or from friendships, or from life, is something they can talk to you about. And so being marked an unsafe person takes no effort at all. The slightest comment, the cringe at a gay couple is enough to be like, “I can ever talk to them.” But to be marked as a safe place, you have to do more. It takes more.

And so I think about that with his mom. I mean, I don’t know if she was a safe place, he definitely didn’t feel like it. But it’s just not equal parts, you can’t do the same amount on either side and be like, we’re good. You have to really overshoot it to be safe. I was just kind of bothered, the whole grandma thing really bothered me. His mom forcing him to be around his grandma who would really put him through it, tried so hard to change him, and abused him in the sense to fight his identity. And I am very big on boundaries, and I can be pretty intense sometimes where I’m like, “if we can’t respect each other’s boundaries, we will not be in each other’s lives.” And so seeing that, I was like, oh man, grandma would not have gotten no visits from me until I knew I could be safe around her, you know?

AA: Yeah, totally. Really, really hard. I wanna go back to the thing that you just said, Stacey, to see if you could remember some examples of people who did go out of their way to make sure that you felt they were a safe place? What does that look like?

SH: I think of the friends that I knew were safe places. All my friends are great. They’re super loving and supportive people. But once again, you’re in the height of the sphere and you have no idea. It’s like cliff jumping, but you can’t see the bottom and you’re like, I could bash on a bunch of rocks. You’re really careful about that and it’s a decision you probably take a long time to make. But the friends who expressed support for queer people put me at ease. And it didn’t just take once, it took a couple times. Like I had a friend who would always talk about a friend of hers who was gay who was getting married, and she was so happy for him. And I was like, she’s a safe place. My sisters who were always very supportive to the queer community, I was like, this is a safe place. My dad and mom– my dad has been so great. I just introduced a guy I was dating to my dad and I was so impressed how warm my dad was. I was also like, “Dad, calm down. You don’t have to go this hard.” But they never expressed support for the queer community or for any queer person I knew. They’ve expressed so much love for me, and for other people and for everyone, but it wasn’t enough for me to feel comfortable talking to them. And so I think you just have to actively talk about it. You can’t just wait for it to be brought up like Saeed’s mom, or he’s guessing or reading her reactions to know if she’s safe or not. Because that’s sometimes all we’re left to, if it’s not talked about.

AA: Okay, that’s really helpful. And I’m just remembering from the book when you said that there were some signs that were not subtle. Like, remember when he would cut out underwear models, like I think Mark Wahlberg? Yeah, his mom would find those magazine clippings and she’d wrinkle, she’d bunch them up but then put them on the kitchen counter for him to find. So she was definitely communicating her disapproval. I had forgotten about that part.

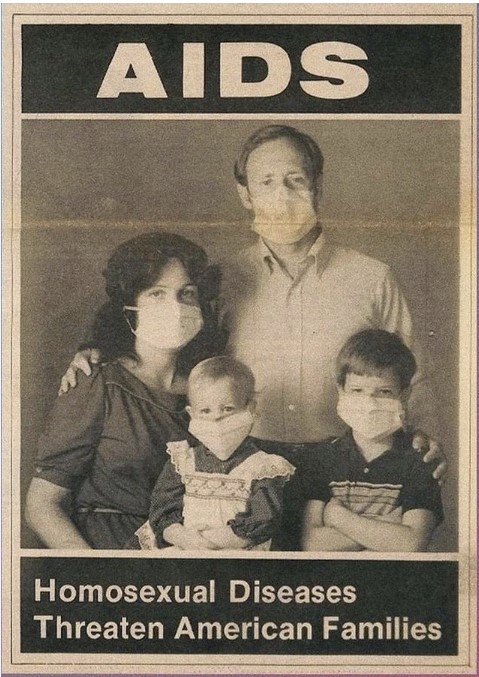

So the next part that we wanted to talk about is a few episodes from Saeed’s life where he’s trying to learn about being gay. Because he’s old enough that he’s realizing he’s gay and he’s like, okay, what do I do? And so he says that one of his first exposures to the word “gay” was when his mom said it because he was learning about a friend of hers who had been diagnosed with AIDS in the 1980s and then tragically had taken his own life. So he was really curious, he’s like “uh oh, I think that word somehow, I think that’s me.” And he needed to know what it meant. So he went by himself to the public library to read books about it. Do you wanna read that next passage?

SH: “All the books I found about being gay were also about AIDS. Gay men dying of AIDS, like it was a logical sequence of events, a mathematical formula, or a life cycle. Caterpillar, cocoon, butterfly. Gay boy, gay man, AIDS. It was certain. Mom’s friend got AIDS because he was gay. Because he was gay, he killed himself. When I sat up to put the books back on the shelf, I realized my hands were shaking. I felt like I had made the mistake of asking a fortune teller to look into my future, and now I was being punished for trying to look too far ahead.”

It is so true and gut-wrenching and heart-wrenching. The information– knowledge is power. And I know it sounds so Schoolhouse Rock and cheesy, but so much is left unsaid and this kid that knows nothing is having to fill it in with his own assumptions, with his interpretation of what is being unsaid. Like his mom’s refusal to talk about it, her disappointment, his grandmother’s attempt to change him. He is fighting for his life to understand what is happening, because all he sees now is that being gay means he will die. When you have gaps in information, you are left to make assumptions. And when you have gaps in information about your very identity and humanity, you have to find out. It’s either finding out by doing, finding out by exploring, discovering, someone teaching you. And if you don’t have that access, that process can be so dangerous. We talk about how straight kids growing up have school dances, and their parents joking about girls and asking them about boys they might be interested in, and the example of their parents or aunts and uncles or something. And gay kids are left with what? Stories about AIDS. And as we come into our sexuality, like every human being does, sometimes it’s stifled and it comes out in dangerous ways. And other times we fight for our lives to learn more information. And it comes from older men. It comes from dangerous chat rooms as we see with Saeed. And it’s such a discredit.

AA: That was the sense that I got to, even though I couldn’t relate personally, but just picturing this poor kid with his hands shaking, terrified, and there’s nobody there to comfort him because he can’t talk to anybody about it. Broke my heart. And then, yeah, I’d love you to talk more about what you just alluded to, were these sexual encounters that he had for the very reason that you just said, there’s no safe way to learn about it. There’s no steps that you can take, holding hands and then your first kiss can’t happen in public, like out in the light. So where is it gonna happen safely? And so let’s talk about that first sexual encounter again at the library.

SH: He’s at the library. He’s got around the firewalls on the internet because you know, internet back in the day wasn’t that widespread or fast. Anyway, he is doing that at the public library. He’s looking up, I think he’s going to like gay chat rooms or he is looking at porn or something. I don’t remember, but something like that. And an older man, like someone’s dad is like, “Hey, I’m like you. Meet me in the bathroom.” And he’s scared and excited and enthralled, but nervous. It’s like he’s experiencing all these emotions at the same time. He goes to the bathroom, has his first sexual encounter with this guy and it’s pretty gross, it’s pretty sad. He’s like a teenager. And it’s so complex, and this is gonna sound so crazy, but at the same time that I was like screaming for Saeed not to go in that bathroom, I was cheering him on. At the same time that I was looking at all the dangerous things that could happen to Saeed from this encounter, I knew that this might be his only chance. How else was he supposed to learn anything? He was so excited to be able to express himself in this way and learn a little bit more about his sexuality. And unfortunately, this experience for him was rare and really informative. And tragic and heartbreaking. And I know so many queer people who have experiences exactly like this, in the sense of almost predatory, an older person, or someone who’s like taking advantage of them. But it’s also their only chance they’ve had to embrace their sexuality, and it comes from the information gaps, right? The information desert.

When you have gaps in information, you are left to make assumptions. And when you have gaps in information about your very identity and humanity, you have to find out…

AA: Thanks for explaining what that feels like. I really honestly hadn’t thought about it until reading this and then you and I talking about it, and that’s a big thing and a big problem. Living in a heteronormative culture where everyone just assumes that everyone’s straight, and you know better than I do. But it seems to me that still, even though we’ve made a lot of progress where you can talk about it more openly than you could a while ago, it’s still not to the point that I would think that people feel just as comfortable. Again, with those first kisses or those first dances or all that stuff, it’s not there yet. At least it doesn’t seem to be to me.

SH: I think it depends on a lot, right? Depends on your community, your culture, your family, you, and your style. I think there are some people in some places that, especially Gen Z, right? They’re not experiencing this pressure to have to define their sexuality. They can just explore who they are without pressure. And that’s not in my community. I mean, I don’t experience that here in Utah and I think we’re way behind. But it seems like it’s happening in certain places, but we are very far from the ideal.

AA: Yeah, yeah. Well, and obviously different areas of the country where there’s literally Don’t Say Gay laws. Like, people freak out when there’s a gay character in a Pixar movie or something where that’s exactly what a queer kid needs to see! See themselves represented so that they can feel more comfortable just being who they are. And again, this topic of their safety, I had not thought about yet. That it does make you really vulnerable to older predators if that’s your only option. Ah! I did not know that.

SH: And isn’t that terrifying? I just think about school dances, like the idea is that we create an environment for kids to explore their sexuality in a way that is under supervision. Because if that wasn’t the case, we’d just be like, go anywhere, go hang out. No, this is a very guided thing so we can make sure that people are protected. And queer kids, at least when I grew up, did not get any of that. We were encouraged to stick to the shadows. We were, if anything, pushed to stick to the shadows. And I came out to my parents when I was 30. I’m 34 now, so not long ago, and it feels like a long time, but my parents felt really bad about it, and they were like, “I wish we would’ve known.” And I asked my parents, I was like, “what would you have done if I would’ve come out to you as a teen?” And from their answers, I was like, “Dad, you do understand how that would’ve been horrible for me.” My dad was like, “oh wait, I would’ve tried to convince you to be straight, maybe, and had you have experiences with women to help you.” And I’m like, that would’ve been terrible. My mom would’ve locked me away, just doing the best she could, but it would’ve been so bad. So it’s like we’re left in the shadows.

AA: Thank you so much for talking about that, Stacey. And that brings us to the end of the conversation. And I just want to thank you again so much for reading the book and discussing this book with me.

SH: Thank you so much for having me!

If I’m arm wrestling someone, it’s a gay thing because I am gay.

I define my identity and the box doesn’t define me.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!