“when women lead they make the changes that need to happen”

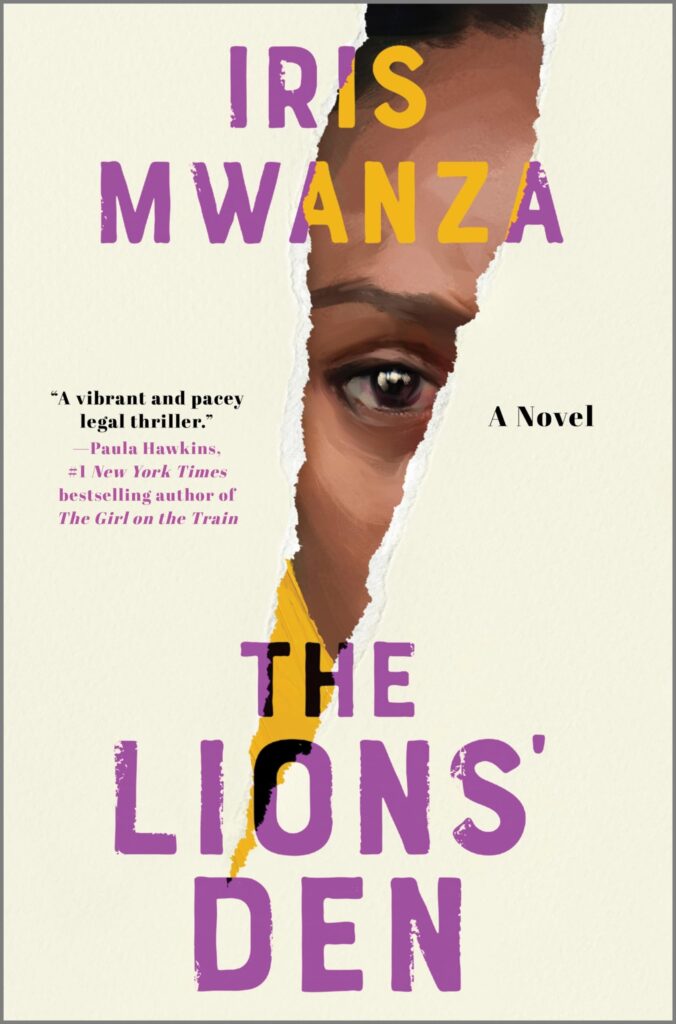

Amy is joined by lawyer and author, Iris Mwanza, to discuss her novel – The Lion’s Den – plus the status of patriarchy in Zambia, worldwide, and the critical role that books play in shaping public attitudes.

Our Guest

Iris Mwanza

Iris Mwanza is a Zambian-American author and gender equality advocate. Born and raised in Zambia, early exposure to inequality has been a driving force in her life – from becoming a lawyer, writing a Ph.D. dissertation on women and children’s rights, a career fighting for gender equality, and now a thriller with gender equality as its heart.

Iris has spent an inordinate amount of time studying and has law degrees from Cornell University and the University of Zambia, and an M.A. and Ph.D. in International Relations from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. Her day job is Deputy Director of the Women in Leadership team in the Gender Equality Division of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and her night job is to write. Her debut novel The Lions’ Den took nine years of nights and weekends to finish.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Stories give structure to our lives. From our very first picture books to our favorite novels, works of fiction form an essential lens through which we can more clearly look out at the world around us and reflect on our own experiences. Novelist Iris Mwanza writes that “Through stories, we can cast light on what baffles, haunts, hurts, and can destroy us. And good stories enable us to learn, debate, heal, and move in the direction for understanding and grace,” adding that this healing, this learning, and debate is her hope for her own recently debuted story, The Lion’s Den. This novel, following the investigations of Grace, a lawyer navigating the corrupt legal systems of 1990s Zambia, is a mystery, a drama, a romance, and I have to tell you, it is undeniably a good story. The sort that sparks thought and challenges readers to reconsider the world around us to become better people, all while being an absolute page-turner. With that in mind, I am so very, very pleased to welcome the author of this book to the podcast today. She’s a novelist, a lawyer, and a gender advocate, Iris Mwanza. Thank you so much for being here, Iris!

Iris Mwanza: Thank you for having me! I’m just absolutely delighted to be your guest.

AA: I’m so thrilled to have you here to talk about your book and to talk about the work you do even more broadly. Iris Mwanza is a Zambian-American author and gender equality advocate. Born and raised in Zambia, early exposure to inequality has been a driving force in her life, from becoming a lawyer, writing a Ph.D. dissertation on women and children’s rights, a career fighter for gender equality, and now the author of a thriller with gender equality at its heart. Iris has spent an inordinate amount of time studying and has law degrees from Cornell University and the University of Zambia, and an M.A. and Ph.D. in international relations from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. Her day job is Deputy Director of the Women in Leadership Team in the Gender Equality Division of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and her night job is to write. Her debut novel, The Lion’s Den, took nine years of nights and weekends to finish. Iris tries to do her part for all creatures, great and small, and is a proud member of the WWF US Board of Directors. I’ve gotta know about all of that, Iris. So if you can walk us through all those parts of your biography, but maybe start us with your childhood and some of the formative factors that made you who you are today.

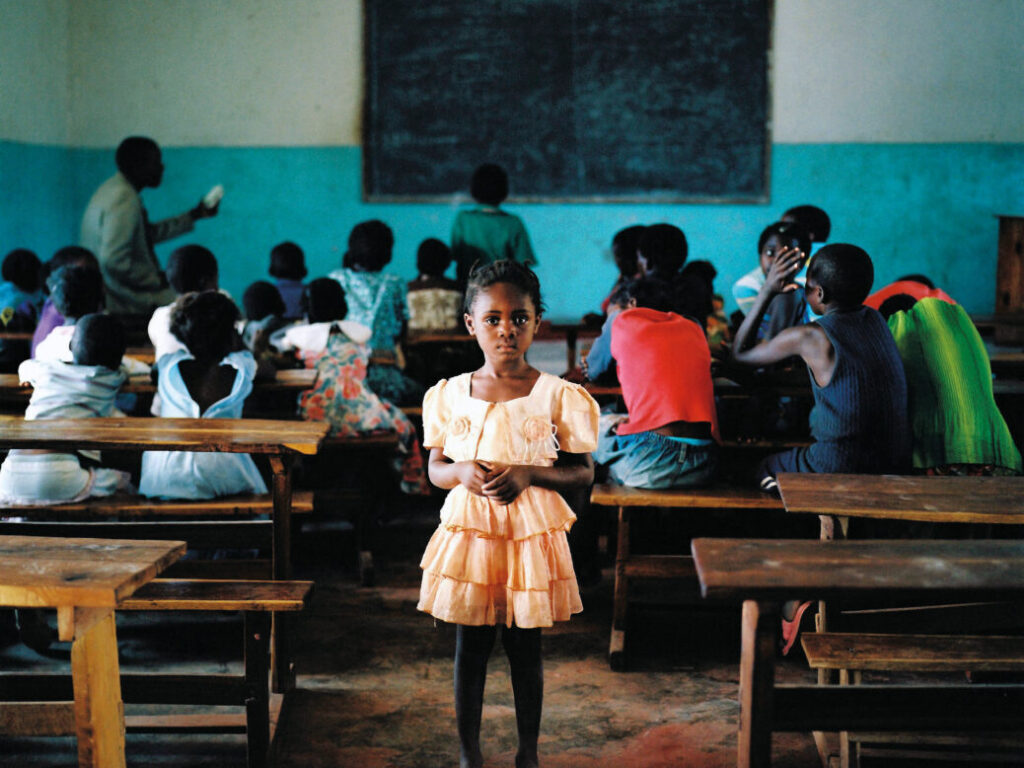

IM: Yeah, thanks. I was born and raised in Zambia, as you noted, and I think I was very lucky because my parents were academics. I had access to books, and that was such a privilege in a developing country to have good access to not just the books at home but the books in the university library. And that was very formative for me, because obviously before you become a writer, you have to be a big reader, at least I believe that. So education was really, really important for my family. And I’ll share a little story with you. In the days when my father was growing up, girls were not educated at all. There were no schools for girls, and there were very few schools for boys. This was in Northern Rhodesia, that was the name of Zambia before it became independent. So my father was educated, very well educated. Ultimately, he got a Ph.D. in economics from Cornell University. But my aunts, who were equally if not more brilliant than their brothers, did not go to school at all. They were able to read the Bible, but that was about it, and they spent most of their life as subsistence farmers. So it was really, really important to my father, who saw this, for us as well, to get a good education. And that started even before we went to school. It started with books. Books were always everywhere. And as you can see, books are behind me. I’m in my parents’ house in Lusaka right now.

AA: Oh, wow!

IM: Yeah, so it was really important for me to get educated. I went to the University of Zambia, got my law degree in Zambia, and then went on to graduate school in the US. And like a bad immigrant, haha, I stayed in the US ever since. But Zambia is really my home. And I’ve had many, many jobs. I won’t bore you with all the details of the jobs that I’ve had, but I think at the center of all of them has been social justice. Social justice is really important to me, with a wee exception of the time that I was a corporate lawyer. But since then, I’ve really found my passion in fighting for social causes in lots of different ways. I’ve worked in global health, I’ve worked in gender equality, which is where I work now, and I feel so lucky and privileged to be able to bring all these different facets of my life to both my professional and my creative career. It does take a bit longer when you have a full-time job, but as you said, nine years. I didn’t think it was going to take nine years. And just to be clear, it’s nine years from beginning to publication date, so about seven years of writing.

AA: Wow.

IM: But I’m very, very proud and very delighted to have this book, this labor of love out in the world, finally.

AA: I’m so impressed by that. I mean, your entire resume is extremely impressive, but yes, to have done a creative project like you said, in the weekends and the evenings and kind of the crevices in between where the actual job happens, that’s super inspiring. I think a lot of people sacrifice that part of their lives, the creative part, and it must have been so satisfying for you through the process but also when you finished it. I’m really inspired by that.

IM: Yeah, and I hope other people are inspired to persevere, because I think anyone who’s written a book knows what it takes. It takes a lot of blood, sweat, and tears, but at the heart of it is perseverance. You’ve got to get to the end. So, if I can do it– hopefully it won’t take all of you nine years, but if I can do it, then certainly I encourage everybody to finish that project. You’re so right, Amy, we are all creative beings. If you think back to the cave people, they were drawing and painting art on the cave walls. It’s in our DNA. I really think it’s very important. But yes, I’m really, really happy that this is done. And of course, as somebody who loves extreme pain, I’ve started on my next book.

AA: Oh, wow. Amazing! That’s incredible. Good for you. That is fantastic.

IM: Yeah, a bit wild, a bit crazy.

AA: Wow. Well, congratulations. That’s wonderful. Well, let’s get into your book. I’m really excited to have you talk about it. My first question for you is for you to set the scene and talk about Zambia. The book is set in Zambia, and as you said, you’re from there, you’re recording from there right now. There are maybe some listeners here in the States who might be unfamiliar, so if you could tell us some very basic information about Zambia, where it’s located, what a reader of the book would need to know about the country as they embark on the story.

my aunts, who were equally if not more brilliant than their brothers, did not go to school at all. They were able to read the Bible, but that was about it

IM: Sure. It’s a pretty small country, I have to say, when I meet folks, they’re like, “Okay, where exactly is Zambia?” It’s South Central Africa. It’s landlocked and it’s not very populous, about 20 million, and it’s spectacularly beautiful, physically beautiful. We have lots and lots of waterfalls in the northern part of the country, we have Victoria Falls, which is pretty famous, in the southern part of the country. We have probably the world’s best safari, and I sound like I’m biased, but honestly, on the eastern part it is really beautiful. But at the same time, there is a lot of poverty. Almost half of the population is living in extreme poverty, and that’s defined by the World Bank and others as living under $2.50 a day. So you have this juxtaposition of extreme physical beauty but a lot of challenges. A lot of challenges not only with poverty, but everything that comes with that. And we’ll get into some of the ways in which poverty plays out in the story, but it definitely is an undercurrent of the life of the characters. The main protagonist, Grace, comes from a very poor, rural background and she has to really, really fight and struggle for herself to get through law school and to become this young lawyer who’s very, very passionate and determined. But also it’s not over for her when she becomes a lawyer. She still has to deal with a lot of discrimination because of her background, because she comes from a poor background, a rural background, because she is a woman, because she is young. I think many of these things are quite universal. The way that discrimination works, I think we can all identify, unless you’re maybe a white, rich male, I think you can identify with how discrimination works to keep people oppressed. Many, many different facets of discrimination, but the way in which it works and the systems that support discrimination and keep people, vulnerable people in particular, down, and we see this play out in many ways through the story.

AA: I’d love to have you talk about the opening of the book. The book opens almost immediately with Grace, the protagonist, being solicited and objectified by a man in power, who’s a police officer. Why begin the book with this imbalance of power and this example of the male gaze? A very powerful man looking at this young woman. It seems like right off the bat you’re talking about those power dynamics.

IM: It’s very central to the story, power is very much a big theme. And I wanted to set the stage immediately because now Grace is a lawyer, and that theoretically puts her in a position, at least it should be, on equal footing or even in a more powerful position than a policeman. And this is not a high ranking policeman, this is sort of your basic officer doing pretty much mundane things in the police station and in the prison. I wanted to show how especially power and culture and patriarchy works in small ways and big ways. And when I say small, I don’t mean to minimize it. I mean to say in your everyday occurrences and experiences and in unexpected ways. She goes to the police station expecting to be respected as a lawyer and to be escorted to her client and have a normal client interview. That doesn’t happen because the policeman doesn’t see a lawyer, he sees a young woman, he sees a rural girl, and in his mind she’s a girl. He sees somebody who he can objectify and treat with impunity. And ultimately, I don’t want to spoil anything, but it becomes a very extreme episode very quickly. But he has zero respect for her, and that kind of theme is perpetuated throughout the story. People feel like they have the right, they’re entitled, and guess what? They’re supported. Because he’s a policeman, because he wears a uniform, he has a badge, he’s in the police station, he feels untouchable, and he can treat both Grace and her client Bessy with absolute, complete, utter disregard and disrespect.

AA: That leads me to a broader question in terms of the setting, and that is, I’m wondering if you could tell us about your own experiences as a woman in Zambia. How are your experiences like or unlike Grace’s? Maybe that’s the first part of the question. And the second part would be how the attitudes on gender in Zambia are different or similar to those in the United States?

IM: Yeah, I think those are great questions. I mean, I think there are some similarities. I did not grow up in a rural area. I grew up in an urban setting in Lusaka. I was born and raised in the city. And as I said, my parents were academics, so middle class but relatively privileged, particularly in a poorer country. So there is quite a marked difference. And I was lucky because I had in some ways a protective cocoon through my father and through my uncles, mainly through the men in the family, because it is a very strongly patriarchal society and particularly at that time in the ‘80s and ‘90s. So I think that I relate a lot. But one of the things that I did experience is sexual harassment as a young lawyer, and that has stuck with me. And I always found it very peculiar, strange, disconcerting, alarming, because I had assumed erroneously that because I was a lawyer, people wouldn’t dare. And this goes back to the scene that you were alluding to, you mentioned in the beginning, which is that Grace believes she’s a lawyer, she knows she’s a lawyer, but she believes that that gives her this protective armor. And the reality is that it doesn’t unless there is a system behind you that will protect you, that there are going to be some consequences and accountability if you sexually harass somebody, they will be held accountable.

And we see how hard that is, sort of dovetailing into your next question. It’s very difficult even in the West, even in the US, which has arguably got very strong legal protections. Yet, before the #MeToo movement and now, even up to today, we have a very good understanding. We have data which supports the fact that these things will continue to happen and they are very, very difficult to stomp out, even in the best circumstances. So where you have societies which are not fully supportive, invested, and really trying to address these problems, recognize the problems, you know, in some places even now, in Zambian society and other countries, people don’t think there’s anything wrong with it. They’re like, “So what? I gave you a compliment.” And you’re sort of like, “Well, no, that’s not a compliment. It’s very insulting. It’s offensive.” And then you have to explain to people and they’re literally confused and taken aback, and then they feel insulted. So you have this curious situation where you’re like, “No, I am the victim here. You’re not the victim.” But I do think that depending on where you are, and the US is a very big country, we’re still struggling as women to educate, to advocate, and then fundamentally to change systems so that women are taken seriously. And I think it’s particularly difficult and challenging for young women, and I wanted to capture that in the story through Grace. She has a lot of things against her but it doesn’t stop her, and I think that’s the beauty of this character. And I love her so much because no matter what the obstacles are in front of her, and their many, many challenges, she is so fierce and she’s so determined and she’s so passionate and she so believes in doing the right thing.

AA: Yeah. Okay, let’s keep talking about Grace because you’re right, she’s so inspiring and wonderful. One part of the story that I wanted to highlight was how she had had a marriage arranged for her by her mother, and her mother had encouraged her to give up her education. And there was one particularly withering statement where her mother says, “If you want to eat, you work. If you want to study, you better get full on your books.” I have to throw in here too, and because my last question was about comparing Zambia to the United States. In my life, right now, I can think of multiple friends of mine who were encouraged to drop out of college once they got married or certainly once they got pregnant, including actually my own mother. My own mother dropped out of college right when she got pregnant with me or maybe once the morning sickness set in. But her own parents also were like, “Well, why would you keep going? Why would you keep spending money on education?” And I have friends that were told that same thing. Although I will say a difference is that then they were also told not to work outside the home because of the conservative religious thing that’s like, “You don’t work, but you certainly don’t get educated either because you’re a woman. What a waste.” But returning to Grace, I wanted to say that that happens everywhere, but going back to the specifically Zambian context, what is the attitude towards women’s education in Zambia now, and what would you say to those who hold these views about women’s education?

IM: I think overall I would say it’s a big country as well, and there is a diversity of opinions. I think that a lot has changed since my father’s generation where there was actually no possibility. It wasn’t even a choice. If there are no schools for girls, there are no schools for girls. And then you educate your boys. But I think part of the culture that builds up around that is a prioritization of boys. Boys will get educated, boys can become breadwinners of a family, girls are going to get married so, as you’ve said, why invest, especially when there are few resources, especially when you have to make choices. But one of the things I wanted to do with Grace’s mother is really bring some humanity to her. She is making, in her mind, the right decision for her daughter. And I think in a lot of families, they really truly believe in their heart of hearts that it’s the best decision that they can make for their family at the time. And Grace’s mother has suffered. Her husband has died, she has lost many children before they reached the age of one, Grace is her only surviving child, and they are starving. They are so poor that they are literally starving, so she sees this opportunity for Grace to marry a chief who is the richest man in the village. It will be a fourth marriage for him, a first marriage for her. But she really does believe that this is the best thing for Grace. This guarantees Grace a good life, and also her a good life, but education seems very remote for her. “I’m going to make a bet on my daughter to go all the way to Lusaka, spend four years, maybe she’ll flunk out, maybe she won’t. Maybe she’ll get pregnant, maybe she won’t.” But this is not a sure thing.

And Grace does struggle to get through university to get her degree. It’s a precious thing for her, but it’s hard for her to get it. And the mom understands that it’s like, “Look, we have a golden ticket right here in our hands versus a hypothetical. Maybe, maybe, maybe, and we don’t even have the money for you to go to university. So why are we even having this conversation? You will marry the chief. That is the best thing not just for me as your mother, but for you. You will have a good life, guaranteed. So stop with these foolish ideas.” And she’s a teenager and she’s of marriageable age. So from the mom’s point of view, I don’t share that point of view, but I did want to bring some empathy into it and really thinking about what is it that makes families support child marriage or sell their kids or do these really heinous things. And often, back to the early point, I think poverty is such a big driver. Poverty and desperation and a lack of choices, or at least feeling that they had no choice. There’s no better choice or no option, and we have to grab this opportunity with both hands and not think about highfalutin ideas of getting an education and being a lawyer and doing all these impossible things that I can’t even begin to imagine because I haven’t even been to school myself.

AA: I’m so grateful that you brought this out, that complexity and the importance of understanding a story within its cultural context. Something that happens so often is that Western readers or scholars, even, will see some sort of cultural practice in another place and bring their own experience and their own lens to it, forgetting that you need a very, very deep and thorough understanding of a cultural context to even understand what the motivations are. And one thing that’s come up for me over and over again that I just keep learning over and over is that most, I would say, almost all parents, to your point, are truly doing what they believe is best for their kids. And if there is a factor, like you said, like poverty or a mother trying to keep her daughter safe, it’s very easy for me to judge and say, “How could you?” For example, foot binding in China. I talked to a woman from China who was like, “If binding the feet of your child means that your daughter will be safe and protected in the world, you’re going to do it.” Even things that are so hard for us to wrap our heads around, even I think of genital cutting, sometimes that’s the motivation. “This is what my mother did, this is what my grandmother did. If I don’t do this for my child, how will they even survive in this culture?” We all just need our children to be safe. That empathy is so, so important, so I’m so glad that you highlighted that, Iris.

what is it that makes families support child marriage or sell their kids

IM: Yeah, I try to bring it to all my characters, but I think particularly the ones who are not the sweethearts and the darlings, the ones who are really complex and are doing pretty heinous things. And Grace actually doesn’t understand and Grace doesn’t forgive her mother. She considers this an ultimate betrayal, a betrayal in the sense of what her mother tried to do to her, but also a betrayal because her mother didn’t believe in her. Her mother didn’t see what she knew she was and what she could be and what she is going to become in the future. And I think that is one of the reasons why Grace just can’t forgive her mother.

AA: Yeah.

IM: So it’s not to condone at all, but just to bring a modicum of understanding of how these things can happen and how they continue to happen in the world and in the context and particularly in poorer countries, I think where it’s much more pervasive. But having said that, as you rightly acknowledged, there are things happening in every corner of the world, be it the West, the East, the North or the South. They are happening everywhere, and I think we want to interrogate the reasons why. Why is this still happening?

AA: Yeah, boy, it’s really touching me in a new way, ways that I need to forgive the women in my life too and remember, just constantly remember that they’re victims of this system and they were doing their best within the system. The bad guy is the system, not the woman who’s also victimized and just trying to make a better life for her kids within this really, really damaging system that we all inherited. So yes, thank you. Thank you for that. Okay, shifting themes a little bit. Another central theme of The Lion’s Den, really rising up in nearly all of its plots, are Grace’s beliefs and feelings around homosexuality, and that is largely rejected and criminalized by the people surrounding her. And it’s worth noting, again, this book is set in the 1990s, in 1990, I think, right?

IM: Right. Late ‘80s, beginning of the ‘90s. Absolutely right.

AA: Okay. So yeah, if you could walk us through what the status was or what the feelings were at the time that the book takes place, the setting of the book, and then how it’s changed in Zambia.

IM: Since the 1980s and ‘90s, I’m really sad to say that nothing has changed. The law is still that on the books, and it’s also important to know that this is a colonial law. This was a law that came about from Britain, became part of the jurisprudence in Zambia and many other African countries, and it has not changed. The homophobia is still extremely strong and there is no– very little, I shouldn’t say no, but there’s very little desire, certainly not in government, to try to change these awful discriminatory laws against the LGBTQ community. There’s almost a denial that you hear oftentimes politicians will say, “This is brought by the West” as though it is not just a natural part of humanity. And it’s appalling. It’s appalling that we’ve not made progress. We’ve gone backwards, actually. Because the world is going forward and yet there’s a refusal. And it’s really hard even trying to market my book in Zambia, believe it or not, it has been really difficult. I’ve heard time and time again, “Oh no, this book is too controversial.” I was like, “There’s nothing controversial about this book.” But the attitudes, particularly around the LGBTQ community, have been sadly regressive. And my hope is that this book provides a vehicle for conversation and an opportunity to even have the conversation and have the discussion and begin to change people’s mind.

That’s why I love books so much, because it’s an opportunity to have a conversation. You could enjoy the book as a thriller and then at the end of it, my hope is that everybody is rooting for both Grace and Bessy. And in doing so, they start to think, “Huh. Wait a minute, maybe I can interrogate my own ideas. Maybe I can have conversations, maybe I can be more supportive and more of an ally of the community that is here.” But it’s really, really difficult for members of that community to live an authentic life. Many of them are not able to be open about who they are, who they love. They have to be in the shadows. And it really breaks my heart. That was one of the motivations for writing the story. I think it’s really important not just for people in the community to write their own stories. I love those stories. I think those are important, but also to show what an ally looks like, what a champion looks like. Grace believes in human rights. That is core to her understanding of the law and of justice and she doesn’t see a difference. And I also believe that there is no difference, if you discriminate against one, you discriminate against all. And that is a message which I don’t think has been emphasized enough. I think we see this often in the way that different vulnerable groups or minorities are divided, and I think that a lot of that is intentional. Divide and conquer, and then it becomes really, really difficult to come together and push for change. So I do hope that there will be more. And while I’m here, I will be trying very, very hard to get the book out there and have these conversations. But I will say, even just talking about a book has been tough. I have been rejected in many places where I’ve wanted to talk about the book. As soon as they find out what the book is about, it’s like, “Uh… No, no, we can’t do this book. It’s too controversial.” And you’ve read the book. It is really not controversial at all.

AA: No. Wow, well, that is all the more inspiring to me, understanding the context in which you’re putting it out there into the world. And I was going to ask earlier, because you write in the author’s note, when you talk about your inspiration for writing the book in the first place, that it came, if I’m not mistaken, it came from a specific event, a newspaper article that you read about a homophobic incident that happened in a Zambian marketplace in the 1990s. Was it that story that kind of inspired the whole idea?

IM: I would say yes, partly, not 100%, but partly. At the time I wasn’t thinking about writing a book at all. I was thinking about who would be the defender of this kid. And the story was that a kid was walking through the market, identified, well, at least the article identified him as a boy walking through the market in a dress. And he gets attacked by a mob and severely beaten up. And there was not one iota of sympathy for the kid. The article was all about how “he” had provoked the mob to attack him. And that has sat with me and haunted me for decades. And as I started to think about this story, it was really to create a character who would be that defender, who would be a protector, who sees the injustice and can see through the systems and her own upbringing and her own education to understand and see humanity, and actually see herself. She sees herself in Bessy, she understands that they’re both equally vulnerable. And there’s a part in the story, very early in the story, where the only time that they meet face to face, she recognizes herself in him. And there’s a sort of a quote where he’s on one side of the table of misfortune and she’s on the other, but just barely. There is a thin line that separates these two and she knows it, she sees it, she understands it. And I would love for all of us to see it and understand it, because we all have vulnerabilities and we’ve all suffered unfair treatment and discrimination. And if we can have that level of Grace’s empathy for others and see ourselves as humans and see others as humans who have inalienable human rights, then I just think the world would be such a better place.

AA: Absolutely. Well, again, I’m all the more inspired reflecting on what a groundbreaking and kind of provocative book this is in your home country. And what strikes me is the role of literature in changing culture. And that has always been true in all places, they say the pen is mightier than the sword. And I think part of why that happens, sometimes it’s a political treatise that’s written that changes culture, but a lot of times it is the books we read and fiction, right? I know even for myself, the characters that I read about became people that kind of inhabited my mind. So when I’m reading, I didn’t grow up Jewish, but when I read about Jewish characters, suddenly that world becomes familiar to me. So if I ever heard an anti-Semitic comment, it would be like, “Whoa, you don’t talk about people like that.” And I did have Jewish friends, but what if I hadn’t? My exposure to the Jewish world might have been just through books. Or, to this point, I have been really… I wouldn’t say transformed, but my worldview has expanded so much as I have read queer stories, both fiction and nonfiction, and my empathy, my worldview has expanded so much. So, again, I guess I’m just commending you for putting this work out into the world because whoever picks up the book is now going to have to confront the lived experience of other human beings that might have different experiences than they do, and that’s so incredibly powerful. It changes the culture at a grassroots level, I guess.

IM: Yes. And this is one of the reasons why I love books, they’re so powerful. But it’s also a reason why books get banned. Books get burned. I think most people understand, certainly governments and people in power understand that books are really critical. They’re critical to educating people, they’re critical to changing minds, they can galvanize, they can push people in different directions, they can enrage. But I agree with you wholeheartedly. Books are really, really important for change. And I really do hope. People might not want to be seen to be reading this book, but there are digital versions and there’s audio, and I think there are still ways in which people can get hold of the book and can read the book and have conversations about the book no matter where you are on the spectrum. And there are a lot of characters in the book who are conservative, and my hope, at least, is that most people reading the book will see themselves through one of the characters who is kind of either very open-minded and liberal and progressive and wanting to protect and defend Grace, but you also have Father Sebastian, who is literally a Catholic priest, and he’s very conservative in his views. He’s not an evil guy, but he is a priest in the Catholic church. And the Catholic church has certain positions still, then more so, but still, and so he will follow the doctrines of the church and the teachings of the church. And it is essentially his job to go out there, so he and Grace have these quite deep and contentious conversations because she is able to see through religion and doctrines and systems in a very, I mean, she’s highly intelligent, but beyond that, I think she’s got a very high emotional intelligence and she can kind of cut through. It takes time and she struggles, but in her heart of hearts, she can see.

And she sees the world very clearly in black and white, and maybe sometimes too much black and white. She doesn’t really do nuance very well. But she sees it very clearly, and that is what informs her belief system and how she acts. And it’s not sort of more institutional. So she has to kind of unlearn what she’s been taught, whether it is in the village and the patriarchal society or whether it is in the church growing up as a Catholic. And I grew up as a Catholic, and I am Catholic, though I obviously have some serious questions for the church, I think the church still has a lot to answer for. But I think these are all things that, as humans, we grapple with. We’ve been taught this, we understand this, we grow up as children and accept that this is what’s right. “This is my place in society, I am a second class citizen, I am a third class citizen.” And as you get older and wiser, you’re like, “Hey, wait a minute. This is profoundly unfair. Why should I be, because of the color of my skin or my gender or my immigration status, why should I be treated unfairly? Why should I be discriminated against? I just want to be treated and seen as an equal person.” And I think Grace looks at the world that way.

Why should I be, because of the color of my skin or my gender or my immigration status-why should I be treated unfairly?

AA: Yeah, for sure. Okay, well, we’ve covered a lot of the serious themes in the book, but one last thing I’d love you to talk about is the exciting thriller element of the book. Can you just talk about that as we wrap up our discussion about the book?

IM: Well, it was really important to me to be able to, yes, talk about important themes that are deep and profound, but really that the book would be exciting and thrilling and a page-turner. And before you know it, most of these ideas and themes are percolating, but the central story should be an entertaining one. Entertaining in the broad sense of the word, not that it’s a barrel of laughs, though there are some funny parts. And one of the things I love about Grace is that she’s so naive and she is funny without even realizing that she’s funny. So I think that there’s a lot to enjoy in the book and the human rights story is there, but ultimately it’s a book that I really want people to read, enjoy, and when they close it, then think about the themes.

AA: I love it. I’ve heard this referred to, well, and I’m sure this wasn’t your intention, but people talk about hiding the vegetables, haha.

IM: Haha!

AA: Like you bake a cake and they don’t know there’s spinach in there. You enjoy it so much. And as I was saying earlier about the books I read as a kid, I didn’t realize I was developing empathy for other groups of people that would make me a better human. I just was reading books because I loved the books and they were great to read. So whether it’s intentional or not, and you’re just a fantastic writer of page-turners, that’s a wonderful benefit for sure.

IM: Thank you.

AA: For sure. And I really recommend that listeners get this book and read it and give it to others and spread the word about this book. It is really fantastic for all the reasons that we just talked about.

IM: Well, thank you so much.

AA: One last thing that I wanted to ask you about before we wrap up, Iris, is your work as the Deputy Director of the Women in Leadership team at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. I’d love to hear a little bit about the work that you do there, and I’d be curious to know also if this work is reflected in your writing at all.

IM: Yeah. I’m very, very lucky to have a dream job, which is working on women’s leadership. I work in the gender equality division, and I would say 90% of the work in the gender equality division is focused on the most vulnerable populations around the world and women, mainly women, and trying to find solutions for many, many of the things and the challenges that women uniquely face. My work in Women in Leadership is trying to accelerate the progress and the numbers of women who are leading in development space, mainly, but I think it is a universal idea because we think, the technical term is hypothesized, but I like to say that I know it in my bones, that when women lead they make the changes that need to happen and not cosmetic changes around policy. These are deep changes that need to happen. We’re talking about normative changes, we’re talking about legal changes, as well as policy changes. So all of this has to happen. And the way it relates in the book is that you see how difficult it is to change culture, to change ideas, to change hearts and minds. It’s really difficult to do. And I find that in my work. Yet, despite that, you meet these incredible gender champions who are going to the ends of the earth to change things. And it’s not because they’re privileged. Most are not from privileged backgrounds, and most have been doing the work for decades before the Gates Foundation interacts or engages or supports them financially, and they are so inspirational. So it delights me to no end when I meet a Grace in the world, and there are many, and I just find that so encouraging that this character that I kind of dreamed up as almost a unicorn actually exists in the world. And I had the honor and privilege of meeting them all over the world as I do my work for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

AA: Oh, that’s fantastic. I love that. Yeah, what you’re saying reminds me so much of a conversation I had a couple of weeks ago about the interaction of policy and culture. And what he said was, “Culture eats policy for lunch.”

IM: Haha! Oh, that’s a good way of putting it. It’s true. It’s so true. And we’re seeing this play out in real time every day. And particularly now in this moment in history in the US, we’re seeing all of this play out. I have so enjoyed this conversation with you. It’s been a wonderful hour together. I’ve had to look at my clock and be like, oh my goodness, it is actually an hour. Feels like a few minutes. We’ve covered a lot of territory and it’s been so, so much fun.

AA: Well, Iris, it has been such a joy to have you on the podcast today. And as we wrap up, I’d love to hear or have you tell listeners where they can find your work aside from The Lion’s Den. And again, please buy this book. It’s wonderful. How can people follow you or learn more about your work?

IM: Online I have a website, www.irismwanza.com. One word. And I am not that great on social media, but I’m trying to be better. So my handle– I’m trying.

AA: There’s no need. Man, mixed reviews about being involved in social media. But anyway, yes, tell us where we can find you.

IM: I know, I know. But my editors and my publicists tell me I must do better. So please do follow me on Instagram @iriscmwanza or on Twitter, which is @IrisMwanza, so I have more than five people, four of which are like Mwanza, and the last one is my husband. So if you are inclined, I will try to be better and post more. The book is available in most bookstores and also, of course, on Amazon. And definitely, if you have feedback for me, I’m really excited to hear what people think about the book. And especially as I’m starting to think about starting to work on my next book, I would love, love, love to have feedback so I can do a better job in the next one.

AA: Well, 10 out of 10 from me. Thank you again, Iris Mwanza. Thanks for being here and best of luck and congratulations.

IM: Thank you. It’s been such a pleasure.

AA: Thank you.

if we can see others as humans who have inalienable human rights

I just think the world would be such a better place.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!