“I am just as human as the man, just as worthy of acknowledgement.”

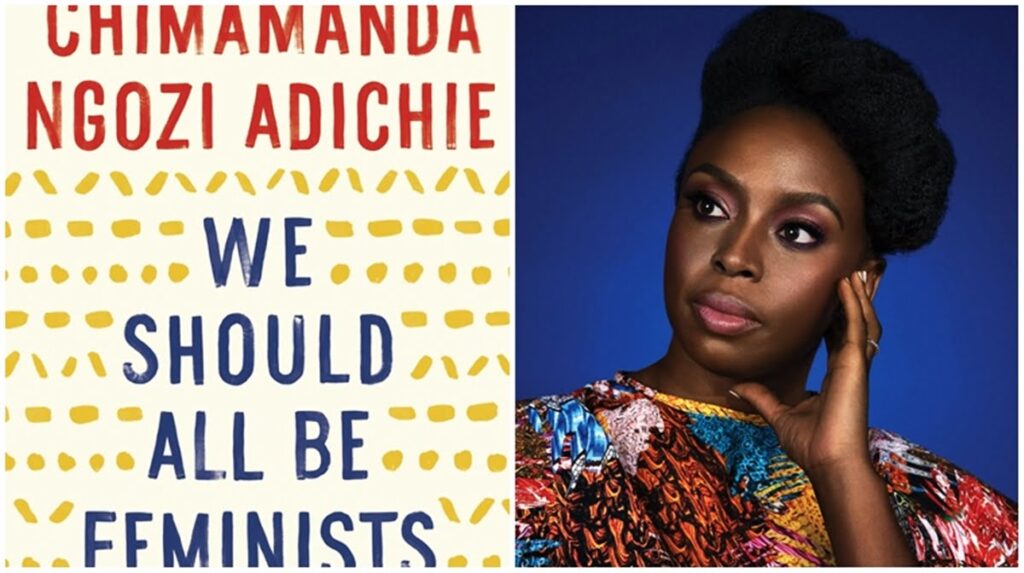

Amy is joined by Kylee Shepherd to discuss We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi as well as Womanism and Feminism on the African continent.

Our Guest

Kylee Shepherd

Kylee Shepherd is a bi-racial student from Bakersfield, California. She is currently a psychology major at Brigham Young University and plans to be an elementary school teacher. She is a founding member of The Black Menaces, an activist group interviewing students and faculty on college campuses with questions that start conversations about racial issues, biases, stereotypes, and more. In her spare time, Kylee likes to the movies, play with her dog, and take naps.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy, I’m Amy McPhie Allebest. For those of you who love Beyonce’s 2013 hit “Flawless” you may remember a clip from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s iconic TED Talk, “We Should All Be Feminists”. Adichie then published a short book with the same title. And this book, We Should All Be Feminists, is a staple in women’s studies and a wonderful resource because it’s so concise and it’s so accessible for any reader. And to discuss the book today I’m excited to welcome back to the podcast Kylee Shepherd. Welcome, Kylee!

Kylee Shepherd: Hi, I’m so happy to be here!

AA: So let’s start out by getting to know you a little bit, Kylee. Can you tell us where you’re from and a little bit about what makes you who you are?

KS: I am from Bakersfield, California. I’m biracial, so my mom is white and my dad is Black. So, growing up there was kind of some confusion on what I really was, if that makes sense. I knew I was Black, but my family just saw me as Kylee, and that’s how I saw myself as well. I am the oldest of three. I have two little brothers, one is eleven and the other is two, so lots of babysitting! I graduated high school in 2019 and started BYU in the fall of the same year. My first year at BYU was pretty rough. I cried every single day and wanted to go home, and called my mom begging to let me come home. I am a psychology major, but after a lot of thought, I do want to be an elementary school teacher, so that will be my focus after I graduate. I probably will go to grad school and maybe have education as my focus…We’ll see. I change every single day. I am a founding member of an activist group called The Black Menaces. We interview students and faculty on college campuses with questions that start conversations about racial issues, biases, stereotypes, all of that good jazz. It is kind of out of my comfort zone, but I do enjoy activism and participating in social movements. And in my spare time, I go to the movies, or play with my dog, or take naps.

AA: That’s great. So would you say, was it Black Menaces that helped you turn a corner and feel more comfortable at BYU? Or what helped you kind of get used to it at BYU?

KS: Oh yeah, so it was definitely Black Menaces. I went home after my freshman year for almost a year and a half because of Covid, and it definitely changed my life. I think I went through depression, I had a new baby brother born, and I was home again so having my mom tell me what to do again was really hard. And so coming back was a complete change again. And so it kind of felt like freshman year all over, like I started over new friends, everything, and then I came out of my shell. And so in that year of like, my depression, I really had to focus on who I wanted to be and who I was. So then I got with my friends and we started it, and my boyfriend is very into political movements in activism and all of that, and so he kind of pushed me along too, which helped. But Black Menaces definitely has made my BYU experience a lot better and more durable, and it’s not as awful.

AA: That’s so great. Well, for listeners who haven’t heard of the Black Menaces yet because you’ve been living under a rock or on a different planet, definitely look at the Black Menaces on TikTok, on Instagram… Where else are you, Kylee?

KS: We have a podcast. Everything that we have is Black Menaces. So we have a podcast, and you said Instagram, and we have Twitter. So anything you can think of besides Facebook.

AA: Awesome. Well, it’s really important work, we’re huge fans. And if you wanna learn more about the Black Menaces, Kylee and Sebastian Stewart Johnson did an episode on season two that I highly recommend. But let’s dig into Adichie’s work and her feminism in Nigeria. We’re going to start out by just learning a little bit about her personally. She’s the author of this book, and then, like I said, her personal experiences that she shares in the book and also in some interviews are gonna give us a window into feminism in Nigeria. So Kylee, do you wanna kind of acquaint us with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie?

KS: Okay, so Chimamanda Adichie is Nigerian born. She is the fifth out of six children. Her father and mother both worked at the University of Nigeria, so most of her childhood was spent on the university’s campus. She began her college career at the University of Nigeria studying pharmacy and medicine, but at the age of nineteen she left Nigeria for the United States. She received a scholarship to study communications at Drexel University for two years, and went on to receive a bachelor’s in communications and political science at Eastern Connecticut State University. Adichie would then continue to complete a master’s degree at Johns Hopkins University in creative writing. While at Eastern Connecticut, she began working on her first novel, Purple Hibiscus, which was released in 2003. She received the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for this piece of work. She would later publish a string of short stories titled The Thing Around Your Neck in 2009. Between 2011 and 2012, Adichie was awarded a fellowship by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, and this allowed her to finish Americanah, her third novel. In 2014, she published a short essay that is based off of a TED Talk she gave in 2012 titled “We Should All Be Feminists”. Adichie has been honored with many awards, multiple honorary degrees, including Doctor of Humane Letters and honors degrees from Johns Hopkins University and Haverford College. Today she is married, has a daughter, and is continuing the work of feminism.

AA: Thanks so much, Kylee. Awesome. So we’re gonna talk about a few different themes from Adichie’s book, and again from some interviews that she’s given and ways that she’s talked about feminism. I’m just gonna dive in and talk about one really interesting topic to me which was that Adichie talks about this discussion in Nigeria about feminism being un-African. So there was a really interesting interview on the website JSTOR, which you usually use if you’re in school, right? We’re both well acquainted with JSTOR. There is an interview between journalist Hope Reese and Adichie where she explains this issue. So I’m going to read a little bit from that. The person interviewing her, Hope Reese, says:

“There’s a scene in your book, We Should All Be Feminists, where you’re giving a talk in Nigeria and someone says that feminism is un-African. What does feminism mean in Nigeria?” And Adichie says, “People say that because they want to find a way to discredit feminism. And also because Western feminism is the most documented, the most known about. So it’s seen as essentially the only feminism.” She goes on to say, “I didn’t become a feminist because I read anything Western or African. I became a feminist because I was born in Nigeria, and I observed the world. And it was clear to me very early on that women and men were not treated the same way. That women were treated unfairly just because they were women. So, I always felt this way. I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t passionate about this feeling of injustice. I started to talk about it publicly with my book called We Should All Be Feminists, which was actually initially given as a talk at a TEDx event that was focused on Africa. My audience was actually African. The people who said, ‘you can’t talk about feminism because it’s Western,’ I think for them, feminism is what they read about. Feminism is Gloria Steinem. Or feminism is the British stuff.”

So this is a really important issue to understand as we talk with African feminist scholars on the podcast, and really interesting as we talk about this book, too. So the reason that some people give why feminism isn’t African, is that feminism is Western. On one hand, Western white feminists are famous for making their own assumptions and completely misunderstanding other cultures. But on the other hand, what Adichie is saying is that she wasn’t influenced by that Western feminism. As she said, “I observed the world and women were treated unfairly.”

And so I just had a couple of thoughts and then I’d love to hear your thoughts about this too, Kylee. In a way, I can relate to this just a little bit regarding the argument that people make when they say, “There’s no problem. Look around you. Women are already empowered,” right? “You have all the power you need.” And the thing that came to my mind from my life was there’s an LDS feminist scholar named Valerie Hudson Cassler, who’s done really great work and is a really respected college professor and thinker. But at least in articles that I read of hers a few years ago, she was always telling Mormon women that they already have the priesthood. She wrote an article called “Ruby Slippers on Her Feet”, which compared Mormon women to Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz, who goes on this big quest to get back to Kansas, only to realize that, oh, the magic slippers that would’ve taken her back to Kansas were on her feet the whole time. And so Cassler thus suggests that Mormon women are silly for being frustrated and sad because we already have the ruby slippers on our feet; we already have all the power we need. We have the priesthood. And for me, this article actually did a ton of damage because essentially, I felt it kind of gaslit me into thinking that the inequities that I was perceiving in my real life were because there was something wrong with me, right? Like, “Oh, I already had the ruby slippers, and so if I’m perceiving this problem”—just use the power you already have. And so I say this because I can relate a little bit to what Adichie is saying, that this argument that feminism is un-African, African culture is already matriarchal. And I have read this, that some people say “African culture is matriarchal, there’s no problem here.” It might feel similar, but maybe even harder than what I am talking about in my life, because I would imagine in Africa it adds a layer of guilt for African women if they do resonate with feminism, because then they’re aligning themselves with the white oppressor. And so it can force African women to choose between being a good African, and thus swallowing harmful gender dynamics that they experience in their real lives. Well, they don’t wanna disparage their African culture, and so then their other choice is feminism, which is viewed as white and Western and racist, which it has been historically. And so I really appreciate Adichie for carving out her own feminism that is Africa-centric so that women don’t have to choose between those two parts of their identity or between those two problems. So what are your thoughts, Kylee?

KS: I actually have a lot, as we think about it. So back to your first point of the article by Valerie Hudson, I think one thing people miss—or that white women don’t realize—is that yes, we’ve come a long way as women as a whole, we got the right to vote and all of these things, but Black women, or just Women of Color, still had and have issues and we still miss out on everything white women do. And I chuckled when you read that comparison of the slippers, it’s like you don’t really realize what you have until it’s taken away from you. So for Black women, it’s like “we all got the right to vote” but then, “no you didn’t.” And so white women got those rights, and white women could do this now, and white women have jobs and Black women, we’re still fighting for those same rights. And my friends and I have talked about this a ton. Like, we have white men who have everything and then we have white women who have just a little bit less, but still a lot. And then it’s Black men who still have kind of a lot, but basically what I’m getting at is that Black women or Women of Color are at the very bottom, and we get the very minimum: everybody else’s scraps. And so that’s kind of why I chuckle at what she’s saying. But Adichie for me is a mentor and a great influence on me because she took something that has been westernized, or in my eyes whitewashed, and taken it and made it her own. Which is why, I think you talked about it on your episode “Double Jeopardy”. And so it’s not like feminism, it’s like womanism. And I think that really stuck out to me because it includes everyone. And creating an equal space is my goal, and I think that’s what Adichie is fighting for. And that’s why she makes it hers.

AA: Yeah, totally. That makes a lot of sense to me. And one other thing that I wanted to highlight from this is that she talks about how on one hand, people say to her that feminism is un-African because in Africa it’s already matriarchal. There isn’t a problem. We already have the ruby slippers, you know what I mean? But then on the other hand, she’ll talk to other people who say that feminism is un-African because literally they say, “It’s natural and God made patriarchy.” And so it’s the actual exact opposite, right? They’ll say, “there’s no problem. Africa’s already matriarchal.” And then other people will say, “there’s no problem. It is patriarchal and that is not a problem.” And she says in the interview that some people will say “Well, Africa doesn’t support feminism because African culture says that the man is superior.” The end. And so, don’t challenge that. And again, I wanna say this is particularly an African issue for sure, but it might have broader resonance with women in other places as well. And I just wanted to ask you, Kylee, have you ever encountered this? Where on one hand people will argue that we don’t need feminism because women are already equal, but then sometimes– I have encountered this, the very same person sometimes will say at another point in the conversation, “we don’t need feminism because it’s natural that men are in charge. Maybe we don’t know why God made it that way, but women just need to accept that in order for things to function well.”

KS: Just the idea of men always being in charge does not sit well with me. Like in my house, my mom runs it, it’s her show, and we all just follow along. And so going to church, where I didn’t have the same access to things as my male peers, it bothered me a ton. And I’ve heard “Oh, you just have to deal with it. This is how God wants things. ”And I think we forget that God also created women. And so I don’t think he ever has wanted one to be better or more superior than the other. I think it’s created from this idea that men have more power and that they’re stronger and that they’re just more capable. And so the church for me is the biggest influence in that idea of “this is how it’s supposed to be, just deal with it.”

AA: Yeah, for sure. So one section that we both wanted to highlight from the book is this place where Adichie is talking to her childhood friend when she’s a teenager. Do you wanna take that part, Kylee? I think that was one that we both were like, oh, let’s make sure we talk about that.

KS: In We Should All Be Feminists, Adichie is talking to her childhood friend and he says to her, “‘You know, you’re a feminist.’ It was not a compliment. I could tell from his tone, the same tone with which a person would say, ‘You’re a supporter of terrorism.’ Because feminists are women who are unhappy because they cannot find husbands. A dear friend told me that calling myself a feminist meant that I hated men. That word ‘feminist’ is so heavy with negative baggage. You hate men. You hate bras, you hate African culture. You think women should always be in charge. You don’t wear makeup, you don’t shave. You’re always angry. You don’t have a sense of humor. You don’t use deodorant.”

Black women or Women of Color are at the very bottom, and we get the very minimum: everybody else’s scraps.

So, this just makes me kind of laugh, the extreme idea of the things that he lists of like, you don’t wear deodorant, you don’t shave, you’re angry. And at first I think it’s funny that we associate shaving and the idea of wearing makeup with women. I think it’s patriarchal. I mean, having hair that naturally grows on your body isn’t feminine? I don’t know why that’s a thing. But anyways, it honestly just makes me laugh because I think this is the idea we get a ton, not even just from African men. I think men in general, where it’s like, you have everything. Why are you complaining? Or the idea that men only see women as things that complain, that we have nothing better to do but sit there and gossip and complain about the lack of things we have in our life. And then the way he associates her with being dirty and smelling… All of it as a whole is just ignorant, in a way. I mean, not necessarily horrible ideas, but just a lack of knowledge on really what it means to believe in women’s rights. Amy, what do you think?

AA: One thing that stands out to me is, I mean, it is totally ignorant and really frustrating. Like all of her friend’s stereotypes that he associates with feminism and then to just kind of hurl all of those things at her is really hurtful, I think, and annoying. But underneath it, I feel like there’s probably a fear. These two are best friends, right? And he’s a boy and she’s a girl. And I feel maybe there’s this fear that she hates men and he’s a man. And so I think that’s sometimes where that comes from. And it reminds me of what you shared earlier, Kylee, about the term “womanism.” And that was new to me when I discovered womanism just by doing the podcast. Alice Walker is the one who coined that term in 1983. Alice Walker is the author of the book and the play The Color Purple. And Alice Walker said:

“Many Black women view feminism as a movement that at best is exclusively for women, and at worst, dedicated to attacking or eliminating men. Womanism supplies a way for Black women to address gender oppression without attacking Black men.” And so again, like you said earlier, I just love that Adichie is claiming a space for women to address the real gender inequity that she sees in her own lived experience in Nigeria without attacking her best friend who’s right in front of her, her dad, her brother, the men that she loves in her life. It’s attacking the issue, not the person. And without attacking African culture! Because she’s not saying, “I hate African culture, or I hate you, or I hate my dad.” She’s saying “there’s an injustice in this culture that I love,” or sometimes like “I love you, you’re my friend. But some of these things that you’re saying are hurtful ideas. Hurtful ideologies. Hurtful habits.” And so she’s hard on systems, but soft on people, which I really love. We were talking a little bit earlier today about a friend that you have. Are you comfortable sharing that story?

KS: Yeah, so one thing that you kind of said that really stuck out to me really quickly is Adichie’s relationship with her dad. And she had a great relationship with him, so it is exactly what you said. She’s not attacking the person, but we are a product of our upbringing, and so when you don’t know anything else, you’re kind of prone to have bad ideas and ignorant thoughts, and that’s fine. I think it’s what you with the information once you’re given it that really makes or breaks who you are. But kind of what you’re saying about my friend… So we are very close, and he’s a feminist and he tries to kind of push for social issues and he speaks out against injustice. However, as a product of his upbringing, there are times where he doesn’t listen to what I say unless it comes from a man’s mouth, which is in this case my boyfriend. And so most of the time I tell him, and then he tells my friend. And so it can be hard sometimes where he’s so ‘for the people’, as I always say, and yet misses a few things from time to time. And so it had to be brought up and we did have a conversation. And sometimes you have to make the people you love really uncomfortable and then, like I said, it’s what they do with that information. And he has changed and he’s tried to be better with it. So the term womanism really did stick with me. That’s kind of why I brought it up earlier. And I think it creates a safe place for Black women and Black men. I think Black men are also hated and kicked and spit on constantly. And so womanism creates a space where Black women and Black men can feel safe. And so it just makes, it makes my little heart happy because I have a good relationship with my dad and my little Black brothers, and so I want them to feel like they can be—how would you say it? Womanist, is that the right word? Yeah. So we all are equal and that’s kind of what feminism and womanism are fighting for.

AA: Yeah. That’s so great, Kylee, and I’m so impressed and proud of you that you did stand up to your friend. And this is maybe silly, but we had on our wall in my house that quote from Dumbledore from Harry Potter where he says that it’s really hard to stand up to your enemies, but it’s sometimes harder to stand up to your friends. And that can be true, so thanks for sharing that example. And that is just like what Adichie is talking about too, pointing out like, sorry, I love you enough to help you grow. So that’s great.

Another thing that we wanted to share from the book that stood out to both of us is this story from her childhood. And this is where she’s talking about how she’s a feminist because of what she saw, she wasn’t indoctrinated by foreign ideology or whatever, she just grew up thinking this is not fair. And so there’s this story where she’s in elementary school and their teacher in their class had said that the highest scoring student could be the class monitor.

And Adichie was the highest scoring student, and so she’s all excited like, “Ooh, I got it, I get to be the class monitor!” And then the teacher switched the rules like “oh, nevermind. The monitor has to be the highest performing student who is also a boy.” And this is a woman teacher who did this. And so little Chimamanda is sitting there just incensed. It’s unjust and she says that the boy who was assigned to be the class monitor instead of her had no interest in that position, and she had really wanted it and worked for it. And so she says, “If we see the same thing over and over again, it becomes normal. If only boys are made class monitor, then at some point we will all think, even if unconsciously, that the class monitor has to be a boy. If we keep seeing only men as heads of corporations, it starts to seem natural that only men should be heads of corporations.” And so here she’s kind of giving her teacher the benefit of the doubt a little bit. Because she’s not a mean horrible person but she hadn’t even realized until a girl won that role, that oh, it can only be a boy. And Adichie is giving her the benefit of the doubt, like, “well, that’s the way she was raised, she just thought it had to be a boy.” But it doesn’t! So Adichie, from the time she was a child, was experiencing this hierarchy of gender where only boys could be in positions of authority. And yet, the next experience she shares is from her friend Lewis, who said to her, “I don’t see what you mean by things being different and harder for women. Maybe it was so in the past, but not now. Everything is fine now for women.” So that’s a little bit like what we were talking about before, but did you have a comment about that, Kylee?

KS: So I do have, it’s not right on the mark of the same idea, but I did work at a cookie shop called Crumbl. It’s really famous in Utah, but it’s kind of spread out over the United States. So obviously being at a cookie shop, we worked with a lot of things like sugar and flour, and those bags can be 50 lbs or even a little bit heavier from time to time. We had to do the runs to go pick those up, and whenever the truck would come back and we would go to unload it, the boys were always asked to help. And so I really didn’t think anything of it at first, but after a few weeks of working there and I wasn’t doing anything one shift, I was like, “okay, let’s go out and go help.” And as I did, one of my coworkers who was helping grab the bags from the truck and handing it to the other employees was like, “oh, Kylee, you need to go back inside. You need to go to the front.” And not in a way like “they need your help” or “that’s where you’re supposed to be,” but it was more exactly “you are supposed to be up front. You don’t need to be lifting these heavy bags.” And it rubbed me every wrong way possible. Especially because I played club soccer growing up, I’ve lifted weights my whole life. And so a 50 lb bag, I guess it’s heavy, but I’m not incapable of lifting it. And so I did say something like, “well, why can’t I help?” and my response was like “you just need to be up front.” And I just brushed it off and that was it. And I was upset and went home and complained to my mom.

But it is what Adichie is saying, where we associate men with certain jobs and we associate women with certain jobs. And one thing women are never really allowed to do is do the heavy lifting around the house or in any setting. And so it upset me that I wasn’t even given the chance. And so, not that I necessarily want to lift heavy bags all the time, but I don’t wanna be told that I can’t do something. And I think that’s exactly what little Adichie was facing. Like, why can’t I do something? I’m very capable and I have worked my butt off for this position. Why am I being told “no”?

AA: Yeah, exactly. The next part that we wanted to talk about is where the author talks about walking into a restaurant or a club in Nigeria. Meaning chronically, like this is how it always goes, whatever restaurant or club that you’re going into. And she noticed that whenever she would go into a restaurant or a club with a man, the server or the valet or whoever it is would just look right past her and talk to whoever she was with instead of talking to her. Which reminds me of what you just shared, Kylee, about your friend a little bit. Maybe just listening to the idea when it came out of your boyfriend’s mouth, but not yours. And so Adichie talks about this, again giving the benefit of the doubt, which I really think is lovely. But she says, “The waiters are products of a society that has taught them that men are more important than women. And I know that they don’t intend harm, but it is one thing to know something intellectually and quite another to feel it emotionally. Every time they ignore me, I feel invisible. I feel upset. I want to tell them I am just as human as the man, just as worthy of acknowledgement. These are little things, but sometimes it’s little things that sting the most.” And so I thought that was, boy, I feel like any woman listening to this can relate to that. Don’t you think? Just like, wow, I could disappear and no one would notice. People will just go around the room and ask like, “what do you do for, what do you do for work?” And skip me! It really does hurt. It really does. So another theme that she talks about is that she has some American friends who are unwilling to speak up and show anger when things like that happen. And she says that her American friends are “So invested in being liked. They have been raised to believe that being likable is very important and that this likable trait is a specific thing, and that specific thing does not include showing anger or being aggressive or disagreeing too loudly.”

That probably depends on your family culture and on your personality, but I would say overall in my life experience, that is for sure the way I was raised. And a lot of my women friends and family members can for sure relate to that. Not wanting to rock the boat, not wanting to be seen as difficult. We’re really trained to be pleasers as women. But what were your thoughts on that?

If we keep seeing only men as heads of corporations, it starts to seem natural that only men should be heads of corporations.

KS: So my experience growing up was completely different. I have a mom who is on guard every single day of her life and will speak up against anything that she doesn’t like. And so I was raised to do the same. When I have friends who tell me to be quiet, or like priesthood authorities in my life from the church not liking my giddiness to just say, “oh no, that’s not right and you’re not going to treat me that way.” And it is funny in my life to see my friends who are super quiet and reserved and then they’re like, “Kylee, you can speak for us.” And it hasn’t changed with me being a part of Black Menaces. That’s what we do, is we speak out for people who might not want to right away. And I am naturally a little bit more reserved as well. So it is kind of cognitive dissonance where I want to speak out, and then I’m also, like you said, don’t rock the boat, but someone has to do it. Someone has to say something, and so maybe eventually we will learn to not teach women that they can’t say anything, and that disrupting the flow is okay.

AA: Yeah, that’s great. So another point that Adichie makes is she talks about masculinity. And I’m wondering if you could read this quote, Kylee, from Adichie’s book where she talks about the “hard man”.

KS: Adichie says, “Gender matters everywhere in the world, but I want to focus on Nigeria and on Africa in general because it is where I know and because it is where my heart is. And I would like today to ask that we begin to dream about and plan for a different world, a fairer world, a world of happier men and happier women who are truer to themselves. And this is how we start. We must raise our daughters differently. We must also raise our sons differently. We do a great disservice to boys on how we raise them. We stifle the humanity of boys. We define masculinity in a very narrow way. Masculinity becomes this hard, small cage, and we put boys inside the cage. We teach boys to be afraid of fear. We teach boys to be afraid of weakness, of vulnerability. We teach them to mask their true selves because they have to be, in Nigerian speak, ‘hard man’.”

AA: So, I could very much relate to this and I thought it was brilliant and super insightful about putting little boys in a cage. But I also had a question, because I had never heard of that term “hard man” necessarily in those words before. And she says it’s “Nigerian speak” and so I looked it up and I found an article called “Nigeria’s Patricidal Hard-Men” by Dennis Onakinor.

And he says, “Originally associated with hard tackling sportsmen, especially in the game of football, the concept of ‘hard man’ gained notoriety in Nigeria in the 1980s when campus cultism spiraled out of control as rival cults battled each other for supremacy, with students of cavalier character, mainly those with little or no inclination for academics stepping up to the fray. Dubbed ‘campus hardmen’ they assumed the role of hitmen in the feuding cults that had no worthwhile objective other than the production of violence. Their activities climaxed in the Obafemi Awolowo University massacre of July 10th, 1999.” They actually killed people! Isn’t that crazy? Okay, I’m gonna read a tiny bit more of this article because it was so interesting. So this author knows that in these, I mean, he’s calling them cults, but I think what he’s really describing are kind of like clubs, kind of gangs on college campuses. And so this author shows a picture of Pablo Escobar, who was a drug lord in Columbia. And so he knows that Escobar is really idolized by these boys in their cult of masculinity, and so he says, “do you know who this is?” to this college kid and this boy says “‘This is Escobar the hard man,’ replied the teenage hawker in response to my query concerning the identity of the man in the photograph, and in the typical manner of a streetwise salesman, he launched into a flattering introduction: ‘Escobar was the hardest man in the world; he was the richest bad guy …’ […] there is a resurgence of fascination for Escobar amongst Nigerian youths, especially the criminal-minded elements. What could have occasioned this renewed interest in the notorious wealthy narco-terrorist who turned his country into a drug war theater for more than a decade? Perhaps, the violent criminality (terrorism, kidnap-for-ransom, banditry, cultism, ritual killing, etc.) currently roiling Nigeria has goaded most people, especially criminals, into embracing the attributes of ruthlessness, brutality, cruelty, etc., all of which they associate with the hardihood of a “hard-man.” And in reality, Pablo Escobar epitomized the “hard-man.” In his 2001 historical blockbuster, “Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the Richest, Most Powerful Criminal in History,” Mark Bowden describes Escobar as a man of “lethal violence” who displayed “casual cruelty.” Indeed, his modus operandi was terror: intimidation, blackmail, kidnappings, assassinations, bombings, etc.”

I just thought this was so interesting that this is what they were idolizing. This is what they thought was their way to have power and relevance in the world, right? And these were born as little babies, they were little boys, they were toddlers at one point. What happened? Why did they start to idolize this horrible behavior? And I just felt like even if these boys don’t grow up to become violent criminals, they do grow up to think that they’re always in charge and that they have to prove their masculinity with money and with violence. And they also say “the harder the man, the more fragile his ego.” Which I thought was so interesting. And Adichie says, “The harder a man feels compelled to be, the weaker his ego is.” And then she says, “and then we do a much greater disservice to girls because we teach them to cater to the fragile ego of males. We teach girls to shrink themselves to make themselves smaller.” And this is the portion that’s in Beyonce’s song, “Flawless”. “We say to girls, you can have ambition, but not too much. You should aim to be successful, but not too successful. Otherwise, you would threaten the man. If you are the breadwinner in your relationship with a man, then you have to pretend that you’re not, especially in public, otherwise, you will emasculate him. But what if we question the premise itself? Why should a woman’s success be a threat to a man? What if we decide to simply dispose of that word? And I don’t think there’s an English word I dislike more than ‘emasculation’. Because I’m female, I’m expected to aspire to marriage. I’m expected to make my life choices always keeping in mind that marriage is the most important.”

So I thought that point was so insightful that society supports, and she’s saying Nigerian society, but I think this happens all over the world. It seems like we teach boys, we don’t teach them this on purpose, but it’s baked into the society, “this is your power, this is your role.” And so underneath she’s saying their ego is so fragile because if they don’t live up to that, then they feel like they have no worth and no value, and then girls and women don’t help the situation because we’re taught to cater to that. To make sure they never feel threatened, to make sure they always think of themselves as in charge or they’re just gonna fall apart. Instead of saying to them, “it’s okay for you to be weak. I love you for who you are as a human being. You don’t have to be this tough guy, this hard man. Just be a person.” So I thought that was really interesting. What are your thoughts, Kylee?

…we do a much greater disservice to girls because we teach them to cater to the fragile ego of males. We teach girls to shrink themselves to make themselves smaller.

KS: Two semesters ago, I took a Psychology of Gender class. And one of the very first activities we did was the professor drew two boxes on the board and wrote ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ over each box. And then as a class we discussed characteristics that fell into that box of what a boy should be and what a girl should be. And then she totally erased everything and said that we put ourselves in boxes. And I think this is where this conversation is leading, where we put men in these boxes and if they step out of the box, then they’re too feminine and all of these bad things. And we associate men with aggression, and then women need to be calm and dainty. And if either two genders step out of those boxes, then there’s an issue with them and there’s something wrong. And so I think that’s where we create little boys who become really aggressive and angry men. And I think it partly is that they were never able to express their emotions as children. And so then we have men walking around with mental health issues and they have trauma because they’ve never been able to talk about it.

And then I think that’s also where we get the idea that women are so sensitive, because we’re taught that it’s okay to talk about things. And then a man is like, “oh, all she does is cry” when in reality, the man needs to cry too. And so I think we forget that we are very similar regardless of body parts. I think that’s literally the only thing that separates a man and a woman. And so, yeah, that’s what I was thinking. One last theme that we wanted to cover that Adichie talks about in some of her interviews is on race. So I’m gonna read a long quote.

“I wasn’t Black until I came to America. I became Black in America. Growing up in Nigeria, I didn’t think about race because I didn’t need to think about race. Nigeria is a country with many problems and many identity divisions, but those identity divisions are mainly religion and ethnicity. My identity growing up was Christian, Catholic, and Igbo. And sometimes I felt Nigerian in sort of a healthy way, especially when Nigeria was playing in the World Cup.” Sorry, that makes me laugh because I played soccer and I remember that. “And then I would think about my nationality as a Nigerian. But when I came to the US it just changed. I think that America, and obviously because of its history, it’s the one country where in some ways identity is forced on you because you have to check a box, you have to be something. And I came here and very quickly realized to Americans, I was just Black.”

Can I speak on that just for a second? That right there—so I’m biracial, like I said in the beginning. I don’t really fit in these boxes very well. And so there is a box where it’s like African American or Other, or something like that, and then there’s the white box. And most of the time they only want you to pick one, so that’s hard as well, because I am both. I am a product of my mother and I’m a product of my father. And so I think picking one cuts off half of who I am. And then even from Adichie’s standpoint, it says African American. She’s not African American, she’s African. And so it’s taking away her identity because Black culture in the United States is very different from Black culture in Africa because they’re not the same. And so I think we are very focused on that in the United States, where you have to be something and if you don’t want to identify as the ‘something’ that everybody sees you as, then there’s something wrong. So continuing on:

“And for a little while, I resisted it because it didn’t take me very long when I came here to realize how many negative stereotypes were attached to blackness. For me, the story that I hold onto as my defining moment of realizing what blackness meant was when I was in college and I had written this essay and it was the best essay in the class, so the professor wanted to know who had written it. I raised my hand and he looked surprised when he found out that it was me.” It’s gonna make me cry. I don’t know why, it happens a lot. “I remember realizing then that, ‘oh, so this is what it means.’ This professor doesn’t expect the best essay in class to be written by a Black person. And I had come from a country where Black achievement is absolutely normal. It wasn’t remarkable to me, the idea that Black people are academically superior. Because, you know, everybody in Nigeria was Black. So the people who were bright were Black. So I resisted it. I didn’t want to be Black. I would say to people, ‘I’m not Black, I’m Nigerian.’ Or another identity that America gives me was African, so that in college people just wanted me to explain Africa. I knew nothing about anywhere else apart from Nigeria, really. Looking back, especially my first year in the US, my insistence on being Nigerian or even African was in many ways my way of avoiding blackness. It’s also my acknowledgement of American racism. Which is to say that if blackness were benign, I would not have been running away from it. And so it took a decision on my part to learn more. I started on my own reading African American History because I wanted to understand. It was reading about post-slavery and post reconstruction, Jim Crow, that really opened my eyes and made me understand what was going on and what it meant. And it also made me start claiming this blackness. I went full circle and started identifying as Black. I think it was a political decision. I decided that having understood African American history, I was a part of it. African American history doesn’t actually start on the slave ship. It starts in Africa. So in a way we’re related. But America will label you Black anyway. So the thing that Black people experience, I experience. I remember, for example, going to the store years ago, and it was a bit of a fancy store that sold expensive dresses, and I just wanted to go and look around. I remember very acutely, you know when somebody wants to make it clear to you that you’re not welcome, but they never actually say you’re not welcome. It was so obvious to me. I just remember being a little shaken by it. I think I hadn’t experienced anything of that sort. Nigeria has many divisions, but it’s really hard to tell who is who just by looking at people. So that kind of immediate and overt discrimination just can’t happen. If I walk into a store in Nigeria, you can’t tell if I’m Igbo or Yoruba. Now, as a public figure, I’m still struck by how in the airport, and this happens very often, I’m jumping in line and I’m going to the first class line, invariably, somebody will say to me, ‘oh, that’s not where you’re supposed to be, ma’am. This way.’ And it’s just an automatic assumption, and I realize it’s because I’m Black. You’re not supposed to be there because you’re Black. The point is that I started out not identifying as Black. Now I do very happily, and also partly because I take a lot of pride. I deeply admire African American history. I think it’s just as full of resilience and I think it is under-celebrated in the US, and I find that quite sad. I think it’s important to acknowledge that to be a Black immigrant is different. To be a black immigrant from a Black majority country is to come with a certain level of confidence. Just growing up seeing Black achievement as normal. And to be African American is to have had a very different experience. There are people who have said to me, ‘oh, you’re not angry, you’re different.’ And I find that deeply offensive because it’s Americans that say this, white Americans. And the reason I find it offensive is that by saying that, what they’re really doing is that they’re denying American history. If they think that African Americans are angry, there’s a reason for that.”

I don’t even know where all my thoughts are, but it hurts to read this. It took her forever to identify as Black. And it’s kind of a joke, but it’s really not funny… one thing that the Black community, I guess what we call it at BYU, we always say that the African immigrants don’t really realize they’re black until they’re called the N-word. And it’s not funny, but we laugh through trauma. But it’s true because they come, and like Adichie said, they’re celebrated. Black excellence and all of the great things that Black people are capable of, that’s normal for her. And so they come here and you’re not African anymore, you are just Black. You’re just seen as your skin color. And so it does take them a second to realize that, I don’t want to say that they’re just like us, but they are, at least that’s how they’re seen in the States. And so I think it upset me because it puts in perspective what it really is and the battle that they have to go through when they come here.

And so the last point that stuck out to me was her identity, as she talks about in the beginning about being Christian, Catholic, and Igbo. In the United States we are forced to pick. And I kind of mentioned it earlier, but it really does create a lot of issues. I think every biracial person has probably said this in their life like “I’m not white enough and I’m not Black enough.” And then in Adichie’s standpoint, she’s not American enough or she’s not African enough if she chooses to be a feminist. And I think that’s kind of the wrap-up for me from this, is that we are so quick to put labels on things that when you don’t fit into a label, we don’t know what to do with you as a society.

AA: Oh, thanks Kylee. Thank you so much for sharing your experiences and your feelings about it. That was really powerful. That brings us to the end of the episode. So for listeners, if you haven’t yet read We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie… Do it! It’s on my coffee table at home and so we just pick it up and read little excerpts all the time. And she also has two TED Talks that are some of the most viewed TED Talks actually on TED’s featured page. And both of them are really excellent. The first might have been the very first TED Talk I ever watched, “The Danger of a Single Story”, and that is such a fantastic TED Talk too. She’s just an important public intellectual and someone that I’ve learned a lot from. So thank you also to Kylee, thanks for being here again. I’m so grateful to know you and thanks for sharing all your thoughts. And listeners again, please check out Kylee and The Black Menaces’ work on all of their channels. It’s just so important. Thanks, Kylee, again for being here.

KS: Thank you for having me.

We must raise our daughters differently.

We must also raise our sons differently.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!