“renovating the house and that we’re a guest in”

Amy is joined by comedian and activist Stacey Harkey to discuss the history of race and gender in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee of the 1960’s, diving into the nuances of how white women and Black men can each hold the roles of both oppressor and oppressed.

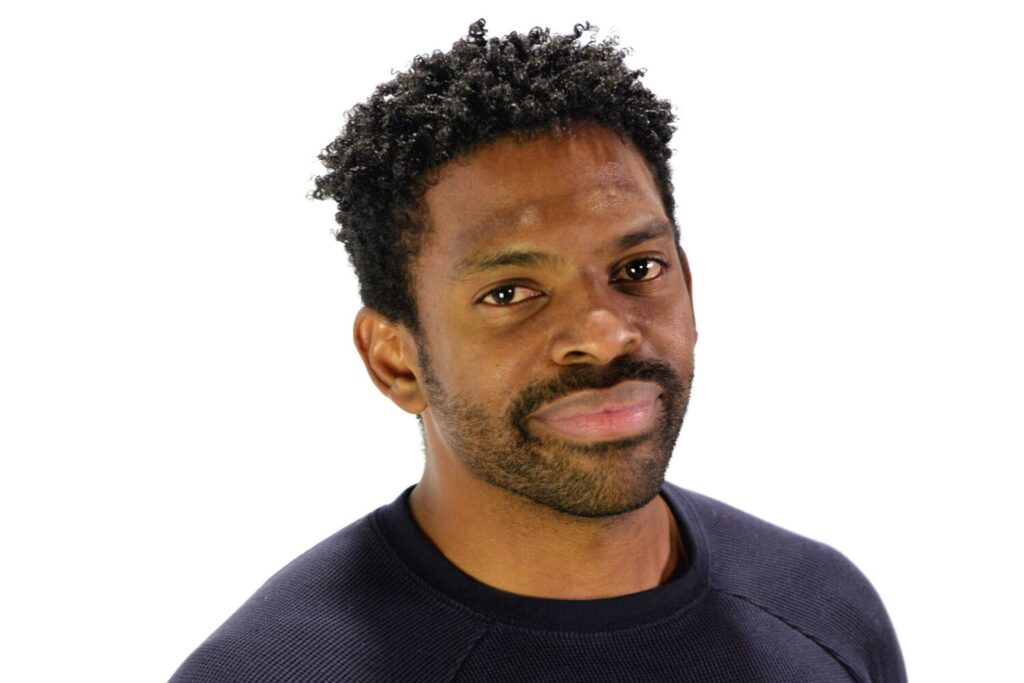

Our Guest

Stacey Harkey

Born in Dallas, Texas, Stacey Harkey considers himself to be a southerner to the core. Always curious and ever annoying he somehow graduated with a degree in Public Relations from Brigham Young University and wrote/acted for the sketch comedy tv show, Studio C. He currently owns a media company with his friends called JK! Studios. He loves playing soccer and the guitar while being equally bad at both. He also believes in the power of an embarrassing moment, a burnt meal, and a extremely difficult challenge.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy, I’m Amy McPhie Allebest. Today I am joined by my amazing friend, you are so dear to me, Stacey!

Stacey Harkey: Keep going!

AA: The one, the only, the incredible Stacey Harkey.

SH: My name is Stacey Harkey. I was part of a sketch comedy group called Studio C, I own a company called JK! Studios. I do comedy but I also have the utmost privilege of being Black and gay in America, living in Utah. And I do personal training things, so I’ve been working with Amy and her family. We’ve had the chance to grow really close and share a lot of experiences like this one. I feel so honored that you have invited me to talk so vulnerably about the topic we’re talking about today.

AA: I’m so excited.

SH: Don’t judge me!

AA: No, me neither. Actually, all the stuff will come up right in the conversation. But I’m so excited. So, we met initially because we were on the same panel about racism and sexism and homophobia, so this is a full circle moment for a right.

SH: Are we talking about homophobia too?

AA: We did, a little bit.

SH: Are we talking about it today?

AA: No, but we were talking about sexism and racism and that’s what we’re going to be talking about today. But yeah, we met maybe two years ago in that context and then just kind of emailed after that. And then I was like, “Wait, you’re a trainer!” And he started training my family. We call you Uncle Stacey, my kids do.

SH: Aw, and I love your kids. I guess I should say that I’m very involved, to the degree I can be, in social activism. I speak at different places. I work with Equality Utah, which is a LGBTQ+ non-profit that’s working for the rights of queer community in Utah and creating connections and building bridges. And so I’m not just like, “I work out and crack jokes.” That is a huge part of my life though.

AA: No, you’re a Renaissance man and you’re involved in so many different things. It’s true. And we talk about all that stuff when we hang out, and we hang out a lot, which is great. And our conversations are often super lighthearted and funny, and then sometimes really deep.

SH: We oscillate between them, which I think it’s going to happen today.

AA: Yeah, I think it will if all goes according to plan. But one of those conversations led to this, because we were talking about the intersections of sexism and racism and how bell hooks has a quote that says that white women and black men both find themselves in a position of oppressor and oppressed, depending on the context.

SH: Wow. Yeah, I think that’s kind of tricky sometimes because especially in the social activism field, we’re always like, okay, who’s oppressed? And it sometimes feels like it needs to be black and white, pun intended. So I think it’s really interesting to wade into this nuance. And it feels a little scary, because what is that going to say about me? Or how is that going to reflect on me, you know?

AA: And there are all the levels politically, and then that’s hard in really close relationships because when an offense happens, there’s so much on the line. There’s so much to lose. And actually, I wasn’t even planning it, but that is the topic today because as we were talking about these white women and Black men being in the role of oppressed and oppressor, I realized that’s literally the topic of my master’s thesis that I wrote. And so then we’re like, “What if we talked about that on the podcast?”

SH: And it was great because I know so little about so much in the civil rights movement, which is embarrassing to say but also honest. I know so little but this has been really interesting and I’m learning so much. Which helps me, like now I show up.

AA: Me too. I didn’t know anything about any of this until I was lucky enough to take a class on it, then wrote a paper, and then in that paper wanted to dig deeper. So now I know a lot about it, but it’s only been in my forties. I didn’t learn this stuff in school. We’re not taught it and so we can’t blame ourselves for not knowing it, but this will hopefully give listeners and viewers some inroads and some points of contact to learn more about this. And maybe we’ll list some additional books and resources for people who want to dig in more.

SH: Yeah, I think it’s good to note too that it wasn’t just like you were taking a fun class and wrote a quick paper. You worked on this paper for over a year. A year of intense research, deep diving, digging. I can’t even imagine what you felt. So this is a thoroughly researched topic that you’ve approached. You’re not in high school writing a paper, you uncovered documents that at least to me seemed lost.

AA: Thank you, I did! It was a lot of work and it was super gratifying and personally meaningful. Thank you. So yeah, we’ll use this story that I think is so important and that I had not heard anything about. We’ll use this story as the frame of our conversation and like a chronological timeline that we’ll follow, but then we’ll drop into whatever issues that come up for you. Just say them and we’ll talk about them.

SH: Good, because they’ll come up. Even the teeny bit, I was feeling it.

AA: Oh yeah. I cried as I was rereading it.

SH: I’m so nervous and excited.

AA: Nervous?

SH: Is there a plot twist?

AA: Yeah, there will be a plot twist. We should stay from the outset, like Stacy said, I researched this for maybe more like two years, and so I do know a lot about it. But you dropped in and read a bunch on some different topics, but then you asked me to not give all the spoilers, right?

SH: Yeah, I wanted to be surprised. It’s history and I’m like, Martin Luther Who did what?

AA: Martin Luther Who, oh my gosh. Well, I’ll start telling the story and then you ask questions.

SH: And if you’re like, “Okay, let me finish the sentence.” I’m already excited.

AA: And vice versa. If I start going too deep or too long then just tell me to come back.

SH: We’re gonna get sucked in. It’s gonna be a screen still of us just…

AA: We could start this story in so many different places, but I think an interesting way of starting it is at the end and then we’ll circle back to the beginning. How’s that?

SH: It’s very Christopher Nolan.

AA: Yeah.

SH: I love it.

AA: Exactly. Okay, so I’ll paint this picture for you. It’s 1964, we’re in Waveland, Mississippi. So picture segregation and super, super, very, very heightened tensions. It’s really dangerous to be a social activist fighting for racial justice at the time. There’s a group that is one of the major groups of the civil rights movement called the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. SNCC, like “snick.” SNCC has gotten together to have a conference, and SNCC is a super democratic branch of the civil rights movement. And it’s the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, so these are young people.

SH: Young adults.

AA: Young adults. Some are teenagers and some in their mid-twenties. And they’re getting together for this conference because they’re at a crossroads. Things are not going very well. And because they’re so democratic, they invite people to write grievances or like, “Here’s what’s going well, here’s what’s not going well,” and suggestions.

SH: Like a little suggestion box.

AA: Kinda, yeah. Totally. They could be short or they could be whole essays, and you can put your name on it or you can write it anonymously. And then the whole group reads it and discusses.

SH: Out loud.

AA: Out loud.

SH: Okay, cool.

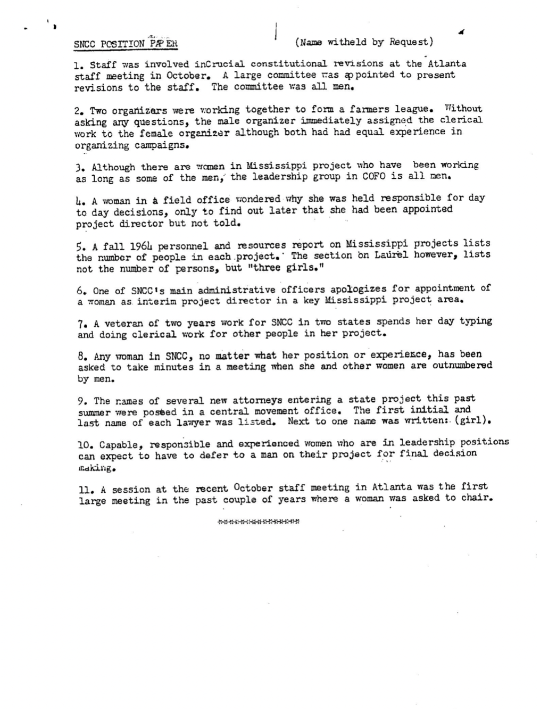

AA: Exactly. The night before the conference starts, everybody’s working on their papers or they’re chatting by the campfire or whatever, four women get together. And we have the records of this, so we know some of the details. They’re sneaking to go into the place where the mimeograph machine is. I did not know what that was. It’s like a Xerox machine but from the sixties. So before Xerox was invented it was to make copies quickly. So there’s this little room that they were using, and they sit at a typewriter and they type out this manifesto of sorts. All these papers were called “position papers”. Like, “Here’s my position on this topic.” They title it “Position Paper #24” and they don’t sign their names. It’s anonymous. And they write a list of grievances of the way that they were being treated as women in SNCC. They slip it into the pile of papers and then they run back to their beds so no one would know. And then the next day–

SH: It’s giving “Who put Harry Potter’s name in the goblet of fire?”

AA: Yes! Why did I not think of that?

SH: I’m ruining this podcast. Haha! They snuck in and Dumbledore’s like, “Who did this?”

AA: Exactly right. So the next day everybody’s reading the position papers, they read each of them in succession, everybody discusses them. And when they get to Position Paper #24, we don’t know what anybody said about it except that a very sexist joke was made later about it. That’s what we have on the record.

SH: What? That’s what you have on the record?

AA: Yes. That’s what we have on the record.

SH: What a time to be alive.

AA: That’s all we have. So the women’s grievances are read out loud. We know that people didn’t know who had written it, and that’s all we know. And then it just kind of falls into obscurity and it’s not mentioned again. It is not a famous paper until–

SH: Wait, no one talked about it in the moment? They just read it?

AA: No, we don’t have a record. We have no record. We don’t know when people learned who had written it, we don’t know if it was discussed at all. All we know is that, okay, I’ll just tell the joke. I’m going to tell it now in case we forget.

SH: What if it’s funny? I’m sorry.

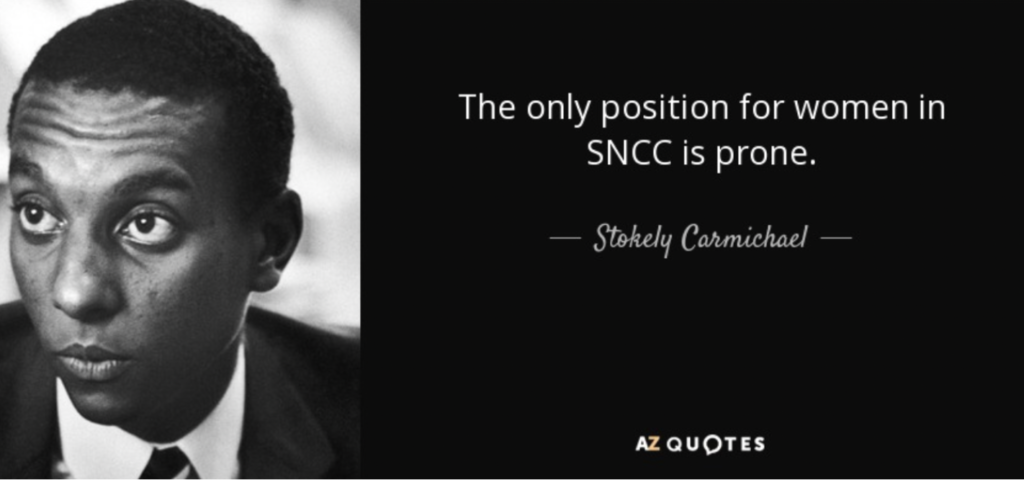

AA: No, you can be the judge, react however you want. So, Stokely Carmichael, and I don’t know if listeners know who Stokely Carmichael is, but you should look him up. He’s a very, very famous civil rights activist. He’s the first person to utter the phrase “Black Power.” He’s like the father of the Black Power movement, he’s the one who shifted SNCC from being, at the beginning their emblem, their motto, was a Black hand and a white hand clasped together. That’s how SNCC started in 1960. By 1966, Stokely Carmichael is leading a march and he says “Black Power” and the whole crowd hears him and starts saying, “Black Power! Black Power!” It shifts toward the Black Panthers, SNCC dissolved, and that comes later. That’s just who Stokely Carmichael is.

SH: Did what happened that day contribute to that?

AA: That’s one way of reading it. It wasn’t by any means the biggest thing, but it happened at a very pivotal moment where SNCC started to dissolve. We’ll get to that later. So he’s in SNCC, and this is before it shifted to Black Power. They’re still really trying to work together, Black and white together. They go out to the dock that night, everybody’s exhausted, they’ve been reading these position papers all day. So I’m just going to say what we have accounts of so we know that this isn’t just conjecture and I’m painting a picture or whatever. We know they were on a dock, we know that there were some white vigilantes nearby. I actually knew this because I got to do original interviews with some of the people who were there and they told me things. They told me things that weren’t even in books.

SH: That’s mind-blowing because the fact that you interviewed actual people in those moments, this feels like maybe my great-great-grandma was around, but this isn’t that long ago.

AA: They’re not even old. They’re not elderly, sitting in wheelchairs. Some of them have started to pass away, but no, these women are still working. They’re still making films. They’re in their early seventies, some of them.

SH: And they remember this experience. Ooh, that says something.

AA: Yes. Anyway, they’re sitting on the dock, their heads in each other’s laps. They’re like hugging, laying down together, you can picture this group of people that are so close despite the tensions that have started to arise. Stokely gets up and they’re talking about the position papers, and I guess maybe the title was like, “What is the position of women in SNCC?” It’s a position paper. So Stokely gets up and he’s like, “What is the position of women in SNCC? The position of women in SNCC is prone.” So that’s the joke. Like a sexual position.

SH: Oh.

AA: You didn’t–

SH: Yeah, I’m just always scared. Like we all have these -isms, what if I laugh?

this feels like maybe my great-great-grandma was around, but this isn’t that long ago.

AA: Yeah, it’s funny. So everybody at the time, and we live in a different time, but everybody said they laughed. Everybody died laughing. One woman who was there was like, “That’s not funny.” Everybody else, including the women, maybe because it was releasing the tension, I don’t know. I don’t need to give them the benefit of the doubt or condemn them either way. That’s what happened. If you google Stokely Carmichael, and this is somewhat not fair to him because he was such an important leader, but if you google him and click Images, that joke is what comes up more than anything else.

SH: Can you imagine being remembered…

AA: I know. It’s kind of not, again, I’m not even gonna say an opinion on it.

SH: I feel like this is a theme of nuance that we’re wading in.

AA: Totally. So basically after that, everything’s forgotten. Including the joke, for a long time people don’t even remember it. But earlier in SNCC there had been a sit-in against sexism, and people just knew that. Nobody was writing it down or anything.

SH: So, just to clarify. SNCC unified and they’re like, “We’re going to fight against sexism together” or this happened–

AA: Racism. Only racism.

SH: Oh, only racism. So the sit-in against sexual harassment was within SNCC?

AA: Oh, I see what you’re asking. Yeah, yeah.

SH: Were they like, “Hey, SNCC, get your stuff together”? Or was it like SNCC banded together and was like, “We’re taking this out.”

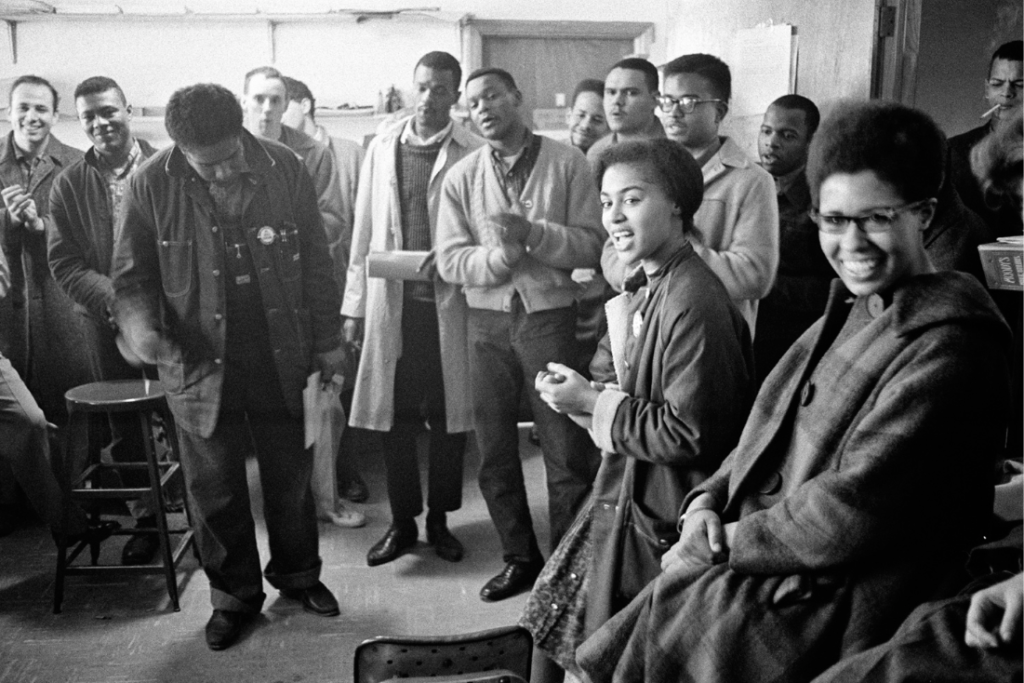

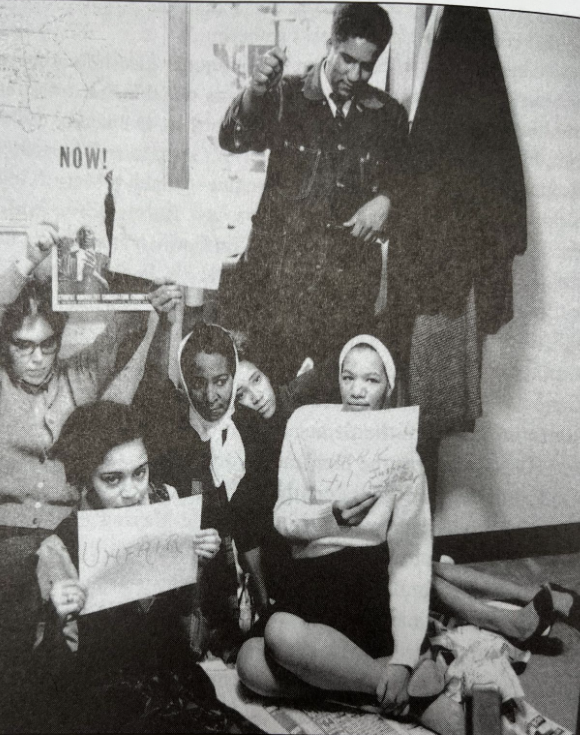

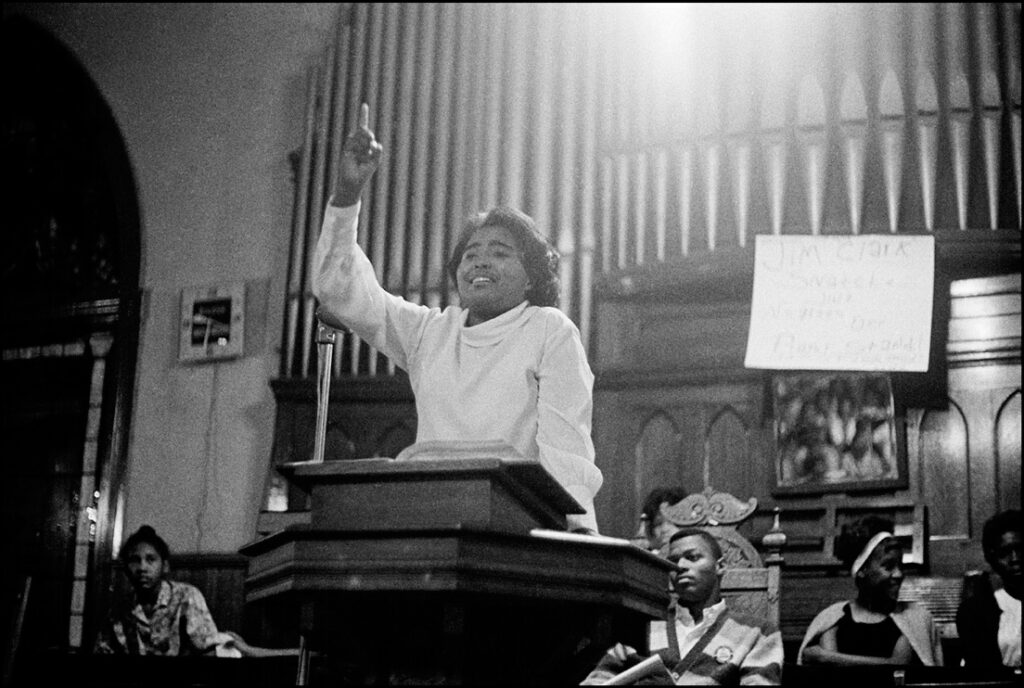

AA: Okay, we’ll pause here because this is important too. A couple years earlier, in a different SNCC office, SNCC had offices all through the South. And in one little office, I think it was their Atlanta office, there were four or five women working with the head of SNCC, Jim Foreman. And when he came back one day they were sitting there and they had made posters. And guess what else? This was such a cool moment in my research. I just happened to be reading somebody who mentioned that they had a picture of it, and I was like, “There’s a picture of this?” And there was, and I ended up finding it. So maybe we’ll put it in the video.

SH: What the heck? You were like sleuthing.

AA: Oh my gosh, I got addicted to being a historian when I was doing this process. There’s a picture of it. Somebody thought to take a picture and it’s just four or five women saying “We won’t do any work until we’re treated fairly.” Because they were having to do all the regular work the men were doing, but also typing up the notes and–

SH: Mimeographing.

AA: Exactly. Cleaning, bringing people coffee, whatever.

SH: Within SNCC?

AA: Within SNCC. Like six people were there and it was in SNCC. So here’s what I’m saying. Of the gender stuff that happened in SNCC, there was this urban legend that this sit-in had happened and that there had been a feminist manifesto written. Nobody knew what it was, there were no copies of it. But later when the women’s lib movement started kicking off in the early ‘70s, people were like, “Wait a second, what started this?” And of course, everybody thinks of The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan, and before that The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir. There were these big books that started changing culture and helping women wake up and seeing patriarchy. But a small handful of white scholars were like, “Wait a second, there was that sit-in in SNCC. And wait a second, there was a feminist manifesto.” So they’re like, it must be because SNCC was so sexist that it made the women wake up to their own oppression and they got trained in activism by being civil rights workers. Then they go north and they’re like, “Now we’re going to use our civil rights training to work for the rights of women in the women’s lib movement.” So they start digging and they find a copy of the Position Paper #24.

SH: The manifesto.

AA: The manifesto. And there was a second one that was written the next year in 1965, and they found that. And they hold it up as like, “Yeah, the Black men were so sexist.” Here’s where race comes in, right? Because it was all Black men that they were accusing.

SH: Like, “Why did this originate in SNCC? We should be fighting for the rights of people.” And so it was indicative, because obviously SNCC was such a horrible environment for women that they had to start there.

AA: Exactly.

SH: And that is true, not true?

AA: That’s kind of the topic of the whole story, so should we start at the beginning?

SH: Grab a blanket and a mug of something warm, we’re divin’ in.

AA: Haha, okay. And again, I want to hear your thoughts on this. Partly because you grew up in the South.

SH: I did, I grew up in the South. And it’s interesting because even some of the little snippets I read before, I was finding myself getting emotionally invested. I don’t want to use the term triggered, as much as I was having strong feelings. And I was like, oh, I’ve had experiences along these lines of white women and Black men, how we interact and correlate and navigate change together.

AA: So where should we start?

SH: Yeah, where do we start? I don’t even know where we’re going back to.

AA: Well, should we start at the founding of SNCC? Maybe we should do that. And this is something you know about, too, with Ella Baker.

SH: Yeah. The question that I have is, why did this happen in SNCC and what were the ramifications? What is SNCC at this time and how did this contribute to a good movement? I’m curious about SNCC and the evolution.

AA: Yeah, yeah. Well let’s start with Ella Baker then. And as you know, Ella Baker was born in, I think, 1903. So she was an older lady at the time that this was happening. And the way this happened is that she was working at the SCLC, which was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, with Martin Luther King.

SH: Martin Luther King’s thing.

AA: Exactly.

SH: That’s what we all know and hear about.

AA: Yes.

SH: The whole crew, that thing. Okay, cool.

AA: That’s that thing. And she had been hired by King and Bayard Rustin.

SH: Bayard was a queer Black activist who was fundamental to the civil rights movement.

AA: Exactly.

SH: A lot of it behind the scenes.

AA: Totally. He planned the March on Washington, he was the mastermind behind that.

SH: I relate. It’s important to see yourself represented.

AA: Totally. Exactly. Basically Bayard Rustin hired Ella Baker and Dr. King was pretty skeptical about it.

SH: Really? He didn’t know her?

AA: Yeah, he didn’t know her. And here’s the thing about Dr. King.

SH: I feel like some tea is coming.

AA: No, I mean, this is like the irony again, I actually feel uncomfortable as a white woman criticizing a Black man. I do. In the context of this paper, and I’ll stop here too and say that when I contacted these Black women to interview them, without exception, they were all very skeptical. Like, why do you want to interview me? What is the angle that you’re

SH: Like you’re going to try to besmirch the people who did all these things in the civil rights movement and all the work we did.

AA: Yes.

SH: Interesting.

AA: And specifically the work that Black men did in the movement, because they’re used to that.

SH: And it’s one thing to criticize a Black man, but Martin Luther King exists as an icon and a hero.

it’s one thing to criticize a Black man, but Martin Luther King exists as an icon and a hero.

AA: Yeah, deservedly, in my opinion. If there’s such a thing as prophets, I believe Dr. King was a prophet. I really do. But what Ella Baker said about him, because she did join the SCLC, but for example, they interviewed her and then they just put her on the books without even extending an offer to her.

SH: They weren’t like, “Hey, do you want to work with us?” They’re like, “You’re on.”

AA: Yeah, so she felt a bit patronized by that. And then there was that quote that you and I were talking about before, which was, “Who was I to them? I was old. I didn’t have a PhD.” You know, she just felt very disrespected. Ella Baker had been working the civil rights movement for decades already. She was this wise, wise woman, and she wasn’t even old either. At the time, 1960, she was in her fifties.

SH: That blows my mind that of the list of things she gives for why she didn’t feel as respected, old was one of them. I feel like that should give her more credentials or credence. But instead I feel like it figures into how we’ve been conditioned to value women and aging. That’s so interesting to me. Like you’re not cute enough to make change happen in the government.

AA: Yeah. They needed somebody to run the mimeograph machine, that was another thing that she said. So she knew her worth, it was kind of tongue in cheek, these comments. But she realized that she was being really underutilized in the SCLC. She’s like, “I’m way overqualified for this.” And they’d make decisions without her. She wouldn’t be invited to the meetings. And she talks about the “male minister’s ego” of being used to being in the front and having a whole congregation saying “Amen” and “Hallelujah” to everything you say. And he was gaining a lot of popularity and notoriety. He was a big deal. And she respected him very much, but he certainly did not treat women as equals.

SH: Interesting. And so is this one of the first accounts of this power balance or sexism in this movement that is trying so hard to create grounds of equality racially? Is that kind of where we see it enter?

AA: I mean, that’s where I saw it enter because that was the specific moment that I was studying. If you look at Pauli Murray, she’s another one to look at. She wrote a lot about this. And she was not quite as old as Ella Baker, but they were friends before, they were doing sit-ins and desegregating buses in the ‘40s before anybody was doing it. They were already doing it. And Pauli Murray didn’t get into Harvard because they were like, “Sorry, you’re a woman.” And anyway, this had been going on for a while. But this is some of the early stuff. So Ella Baker is ready to leave the SCLC. And at this moment in early 1960, you have the lunch counter sit-ins in Greensboro. So everybody can picture that, we do learn about that in school, at least.

SH: We have black and white pictures of people sitting at the counter and people yelling at them.

AA: Yeah, exactly. These are college students and they’re starting to organize all across the South. Greensboro is the one that’s most famous, but it’s spreading like wildfire. Everybody’s hearing about it. So the older guard, the SCLC, is hearing about the young people taking things into their own hands. Which we’ve seen in our lifetimes a little bit, right?

SH: It’s like that vitality, that energy, almost that youthful brashness. Cool.

AA: Yes, exactly. So they’re like, “We have to get in on this and harness this. This is so great.” Because they had already been working, but there’s this new movement and Dr. King wants to bring them in under the umbrella of the SCLC, where he’s kind of the head honcho and he’s going to be in charge.

SH: They have the structure, the organization. Like, “Come work for us. Bring that energy, let us harness it and guide you.”

AA: Exactly. And Ella Baker says, “No, I don’t think there should be a leader.” She’s an anti-hierarchy person. She’s a democracy person.

SH: Interesting. Which makes sense, because someone who had experienced hierarchy in so many platforms, whether it’s racially or through gender, through sex. You probably see the value in having everyone’s voice be heard. That would be more important to you.

AA: Yeah, that’s a good insight. That’s definitely true. So Ella Baker convenes a conference at her alma mater, Shaw University in North Carolina, and it’s on Easter weekend in 1960. She gathers all the students and says, “Listen, you guys are amazing. You’re doing amazing things. You should get organized. How do you want this to take shape?” And Dr. King gets up and talks and he’s like, “Come to the SCLC.” And we have records of students who were there and who listened to them both speak, and they said that when Ella Baker got up to talk, she wasn’t saying “don’t go with Dr. King”… but she was saying “don’t go with Dr. King.”

SH: Don’t go! The Martin Luther King?

AA: The Martin Luther King. Yeah. So she says you really have the ability to govern yourselves and you can do this with a really flat democratic structure. You don’t need a leader. Strong people don’t need strong leaders. And so the students voted and they voted to do their own thing.

SH: So SNCC stayed separate from the SCLC?

AA: Yes. They worked together, and they worked with lots of different branches of the civil rights movement. They would work in concert with one another, but they had their own branch.

SH: Got you.

AA: They had their own branch and they had an executive director. But Ella Baker was always just in the role of a mentor and she didn’t like it when people would call her the founder. She said, “I’m the godmother.” She just was not a hierarchy person. And everybody loved her no matter what happened. She was this really warm, nurturing, but very smart and very experienced. Again, not a matriarch because there’s no -archy. But she was just this resource to them. There are pictures of Stokely Carmichael and some other people weeping at her funeral. She just was so, so important to everybody.

SH: I think that’s so interesting to see that these movements, almost like the things Dr. King says, we almost regard them as scripture. We post about them for the holiday, we sit with them, they have a lot of meaning. And he did so much, but he wasn’t perfect. The movement wasn’t perfect. It wasn’t like “this is the way for us to reach harmony and perfection.” It was just a step, albeit one that still had a lot of flaws within it. Interesting. That feels almost wrong to say, you know? I don’t know, it feels like I have to be like, is it bad or good? And that is just not how people or history are. And so this is my first taste of like, “Hey, Stace, wade into the nuance. Can something be good and have problems?” Yes.

AA: Yeah. It’s hard. And again, to criticize Dr. King, I want to establish again that I do think he had incredible courage to do what he was put on this earth to do, and the movement wouldn’t have done what it did without him. So I have utmost respect for all of the good he did, and I do hold him in the highest regard. And like you said, we talk about this all the time, about nuance and about being able to hold multiple truths at the same time. They don’t negate each other. They just all are.

SH: They all are. And I think that’s a good time, if you’re looking for who’s right and wrong in the situation, this may not be the episode for you. Because we are not here to say bad or good, we are here to explore this topic and then make it relevant to us. To see how it relates to us now.

AA: Yeah. And let’s make sure to do that. Let’s remind each other at the end to at least hint at the through line that really has impacted things through to this day. Let’s not let each other forget.

SH: That’s so interesting that Ella Baker didn’t stand up and say, “We gotta stop Dr. King because he’s doing these things.” Why not?

AA: Because she didn’t believe that, at least what I am recalling. And for people who are interested in digging into this more, there’s a wonderful biography of her by Barbara Ransby. Great biography. So no, I think she definitely knew that King was so necessary and was doing what he was supposed to do, but I think she saw real potential for these students to govern them. Interestingly, when she starts SNCC, what I’m remembering is that the very first person that she brings on is a white woman, much younger, named Jane Stembridge. And so right from the very beginning, from the birth of SNCC, you have Black and white together with those hands. And they very famously had all of these beautiful songs and hymns, and they would sing “We Shall Overcome” all the time. And one of the verses that I didn’t know until I was researching this is, I’m going to get choked up. There’s lots of verses to “We Shall Overcome” and one of them is “Black and white together. Black and white together.” And if you hear it song like it’s–

SH: Like [hums tune].

AA: Yep.

SH: Oh, interesting.

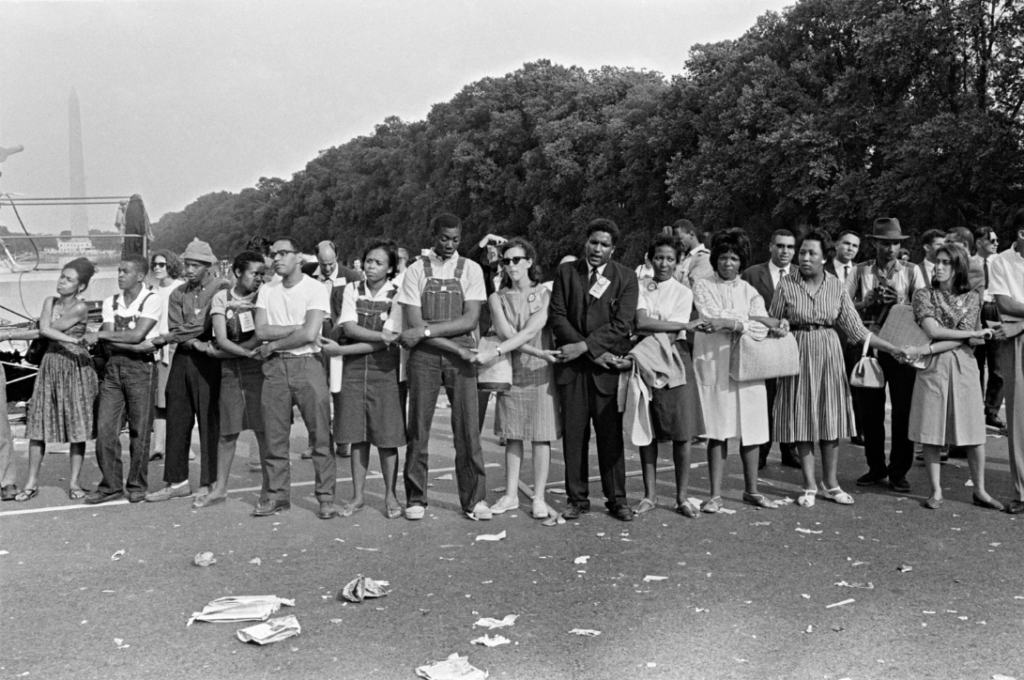

AA: Yep. That was SNCC. And so what you have is, I believe at the beginning it was 80% Black. And again, it was mostly students with a bunch of adult mentors who were helping them. And they’re organizing, doing things like desegregating buses, like the Freedom Rides where interstate buses were segregated. And to desegregate them all you do is just sit on the bus in a group.

SH: I can do that.

AA: Yeah, but when they would arrive at the bus stop sometimes there would be mobs of white men waiting for them with baseball bats.

SH: Who has time for that? Back in the day like “The negros are at the bus again, let’s get our baseball bats.” Don’t you have jobs? That’s wild.

AA: Yeah, it was really bad. And SNCC went to the places where it was the worst, like Mississippi, the rural, rural deep South. John Lewis at one point got his head smashed in, cracked his head. There are pictures of people bleeding. In fact, Diane Nash, who was this young, early-twenties woman, would stand by the buses and she had people sign their wills before they got in these buses. There was a real danger that they would be killed. It was that dangerous. Just to sit on a bus together they were risking their lives. The other danger was that you could get roughed up at the sit-in, for example, but then the other danger was that when the police showed up, these were white supremacist police who would take you to jail and they would often get beaten in jail. They would beat the women in jail.

SH: Oh my gosh.

AA: I mean, not every time.

SH: No, but there are accounts of that.

AA: Oh yeah.

SH: Is not like they’re just beating up people who are resisting. It’s everyone. Pregnant, senior citizens, young women, everyone’s getting beat up. Oh my gosh.

AA: Yeah. And you think, like, this is America. We have a right to assembly, we have a right to free speech, that’s in our constitution. So this is unconstitutional oppression. As I was reading it, I’m like, this is not legal! You can’t take someone to jail for peacefully sitting in a chair. And yet they did. They just completely, flagrantly disregarded the values that our country was founded on, of peaceful demonstration.

SH: Whoa. So that’s what we’re seeing with SNCC right now, in the midst of this movement of Black and white together, making change, taking chances. Everyone’s taking risks. Men and women, Black and white.

she had people sign their wills before they got in these buses. There was a real danger that they would be killed.

AA: Yep. All together.

SH: Wow. So SNCC is killing it in the civil rights movement. Super successful, we see the results now. It sounds like everything was perfect.

AA: Yeah. And in many ways, you see accounts that people wrote in their journals that it was as close to almost a utopia as you could have. There was really so much love. So much love. But there were little fissures that were starting to form cracks. You know what I mean?

SH: Why?

AA: Well, one thing that caught my attention was that in the essays that Black women wrote about why they got involved in the civil rights movement, they would say, “My grandmother was enslaved and my parents were sharecroppers.” And that just struck me that they see themselves as just a point on a timeline. They could have just said, “I joined SNCC in 1961 when I was at Shaw University,” or whatever. It started with their enslaved– And again, that’s as close as we are. Like, whoa, they’re not even old. We’re so close to them. That’s true. They also were so close. Ella Baker was born less than thirty years after the Emancipation Proclamation. She was raised by a woman who had been enslaved.

SH: Holy…

AA: So that’s how close we are to it.

SH: I can’t fathom.

AA: It’s unbelievable. So that’s one thing, I was like, oh, these Black women are talking like we are talking right now to their white sisters and brothers. And they’re hugging each other, but in their minds and their bodies they are carrying things that they wouldn’t know to say or say to anybody. But that’s what they’re approaching this situation with. Meanwhile, white women are coming to it with completely different lived experiences. Completely different. And I wondered if that’s one thing that contributed, is that they came to each other like, “We’re all in this together!” And then they realized, like, “Wait, why are you doing that?” Because of their different backgrounds.

SH: I can relate. I think about how in the midst of George Floyd and the notoriety of Black Lives Matter growing, I sat and thought a lot because there were so many frustrations I had with white people who were wanting to help and do the work. And I kind of settled with the concept, it’s like, my dad has stories of being rough-housed and thrown around by police. My grandma has stories of having to hide and navigate being a single mother in the South or even the Midwest. And so I think about a lot of the crap that we’re dealing with, and I kind of feel like I inherited fine china. Like it was something that was handed down and it just amasses, there’s so much pain and experience behind it, and it’s so fragile. None of my white friends could really understand that. In the meantime it felt like they were also stepping into it for the first time and I’d been sitting with this generational pain for my whole life. So I totally see that concept of like, we want the same thing but there are some big feelings and experiences that can’t be shared through a little conversation. How would people know?

AA: That reminds me, because you grew up in Texas. So your dad, when was he born?

SH: He’s like 60.

AA: Okay. Did he experience segregation?

SH: Yeah, actually he was bussed. It was in Oklahoma and his parents were educators. My grandma was a teacher, her dad was a principal, and he started the first school for Black people in this area because the schools that Black people could go to were so far away. So my dad and his siblings went to the school and then they started integrating schools. And they bussed my dad and some friends to white schools, and they said it was incredibly– My dad’s such a positive person, he was like, “We made the most of it, and once we were on the football team people are nicer to us.” But he said they had to really stick together. And that’s my dad’s lifetime. Isn’t that cuckoo bananas? It’s wild.

AA: It is. I never really realized how hard it would be for those kids. And some Black scholars at the time were like, “We don’t want our children to have to go integrate and be bussed into racist white schools. They’re going to get bullied, that’s going to be terrible. We should just stay with our own communities.”

SH: And I see that’s already a complexity, that’s a conversation to have with other Black people about integration. There is this concept, and I think it might come up as we talk more, and I realized it when I was having a conversation with a white friend about this. It was a situation that went down in pop culture, and we were going about it so passionately from slightly different angles. And what I realized is that the angle at which I was looking at it is about protecting the individual. How do we go about protecting the individual? And they were going about it like how do we enact positive change overall? But we wanted the same thing, overall safety. So when you look at bussing, for example, you’re like, we need to integrate society. How are we going to put a dent in racism if we don’t even interact with people who are different from us, if we keep it separated? And that’s from the angle of society needing to change and become better. But on one end, I look at it and I say, can you imagine the danger? Who wants to sacrifice their kid? Who wants to say, “Yes, we need to integrate so I want to put my child into the most hostile environment for the greater good of white people and hopefully black people too.”

But I think at a point Black people were like, “We want the same opportunities, we don’t want to be treated poorly.” And so I look at this thing where it’s like, yes, change society, make the world better. We need to do that. But also I’m like, what about the individuals? What about your personal safety? Thinking of my dad or a family member. I graduated in 2006 from a town called Little Elm in Texas, and my little sister was verbally tortured in school, in church. In the South, in Texas, she was made fun of for being Black. This is in our day and age. And it was probably so important for some people to have interactions with a Black woman, but also the crap my little sister went through. You know what I mean? The nuance that society needs to change, but why does the burden have to fall on already vulnerable populations?

AA: Yeah, totally.

SH: It’s complex. That was a huge tangent.

AA: No, that’s actually not a tangent at all. And that was something I learned. Again, you learned it from your lived experience, and for me it was in a book. But I was surprised to read about a lot of Black SNCC students, volunteers, whose families basically disowned them when they joined SNCC. Because they were like, first of all, you’re putting yourself in danger and also like, we worked so hard for you to go to college so that you could have a good life and just buy a house, buy a car, and carve out a good life. Things are getting better. And if they went to SNCC, sometimes they dropped out of college. And so they’re like, “We worked for you to go to college! What are you doing?” And also, “You’re getting arrested! Are you kidding me?”

SH: Keep yourself safe.

AA: Keep yourself safe.

SH: It’s like, “I’m trying to change the world” but half the world doesn’t even like you. Keep yourself safe.

AA: Exactly.

SH: I don’t know. I feel like it’s just that complexity, right? If your daughter was like, “Mom, I’m going to go do this thing where I might die.” You would probably be like, “It’s so noble,” but would you also be like–

AA: Let somebody else do that. Yeah no, sorry. It’s hard and complex.

SH: I can one hundred percent, like if one of my nieces or nephews or something… I’m like, no! What are you doing? That’s from the personal safety aspect and that’s tough. Those SNCC students… Probably helps to not have a fully formed prefrontal cortex.

AA: Yeah, right?

SH: Jumping into those situations like heroes.

AA: Exactly. They weren’t jumping in maybe as scared as they would have been if they had been older. But yeah, so, so courageous.

SH: So, you mentioned these fissures, but what are some of these experiences that Black women and white women were bringing to these? What were these tensions?

AA: One of them, like we talked about, was the legacy of enslavement. Some of them had literally come from sharecropping families and the people that they had been raised by, or at the very least their grandparents could tell stories of enslavement. So they were bringing that. Another thing was the legacy of segregation and lynching, and a lot of Black women brought up, they said “We were the Emmett Till generation.”

SH: Yes. I heard a lot of people had, I think I read in your paper that a lot of people had pictures of Emmett Till. It was a huge thing for them. Kids growing up with George Floyd and being aware, or I imagine if you’re white and you’re hearing that for the first time and you’re mobilized, or you’re Black and it feels like the final straw. You’re like, “It’s gotta change.”

AA: Yeah. That’s a good comparison, I think, to compare to George Floyd. Because it was that huge, huge moment. And I know you know this, but for listeners, when Emmett Till was murdered, his mother chose to publish the photos of his body in Jet Magazine so that it could be seen, and that was why it became such a moment. Because this happened all the time. Lynchings happened all the the time, as you know. But they said “We were the Emmett Till generation.” They were little kids. And like you said, the awareness and these were formative years of them learning how the world is. And they talked about their parents hiding the magazine so their kids wouldn’t see it because it would be so disturbing to them and so sad.

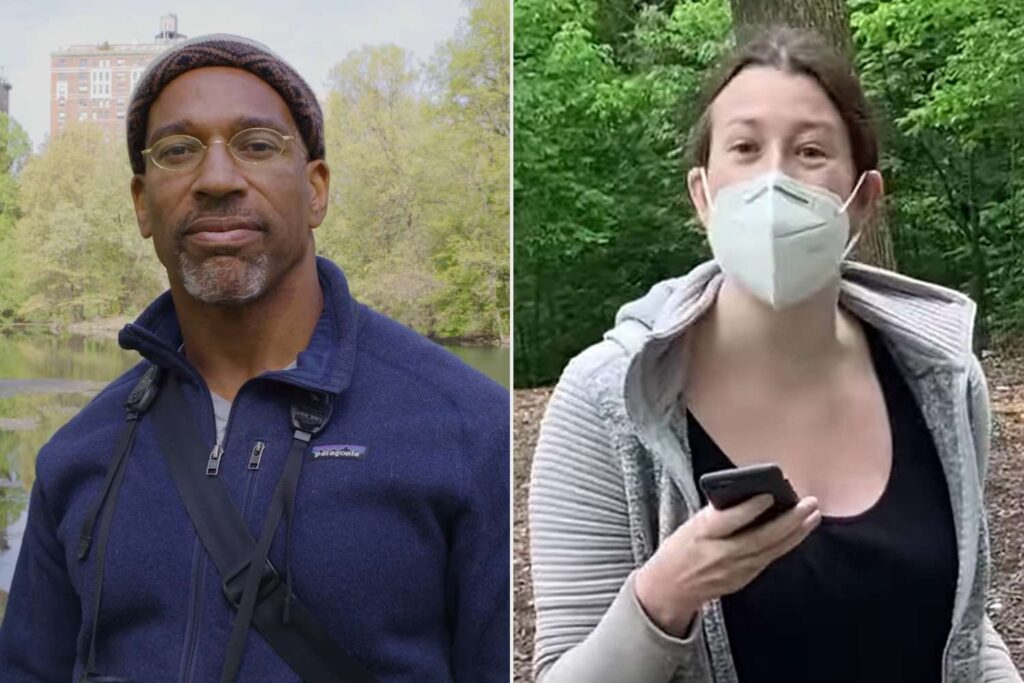

Just knowing that they had those memories and eavesdropping while all the adults were talking about it. And Emmett Till’s murder, again, obviously this was an act of violence by a white woman. A white woman got this Black boy murdered. And so I would imagine that that would impact the way they saw white women. Is anything coming up for you?

SH: I’m thinking about the power, and I feel like we see that in the news a lot. I think of the Black guy who was bird-watching at the park and the white lady had her dog running around, and he said it was the park rules for the dog to be on a leash and it was scaring the birds. And she was trying to call the police on him. It is such a tie to Emmett Till of being seen as weak and weaponizing that, and weaponizing Black men being seen as being monsters. I think I was talking about this earlier, but I was this 10-year-old gay kid growing up, no one knew I was gay back then, I assume. And I had a white girl claim I assaulted her, and it was a huge deal at my school. I was in sixth grade and she was like, “He sexually assaulted me.” And I didn’t even know what the terms were back then. My dad had to be at the school, there were conversations with the principal, and their compromise was for me to be expelled. That was the best case scenario. And that’s my history of someone just claiming something and being like, “Of course this young, Black, vagrant monster would touch you like that.” It wasn’t even a conversation. I don’t even remember being in the room, I don’t remember sharing my account.

So, I see that history and I experienced that and I’ve seen it in other situations. I mean, even to be more clear at work. White women would, it happened twice, they would lose their cool on me. And I was villainized for it. I was villainized. This is really getting into the tea, but that’s one of the reasons why I quit. Because I was like, I can’t be safe here. There were little situations where I’m like, “What’s the schedule like?” And then someone who had been stressed out just loses it on me. And then everyone’s like, “Why are you being this and that?” And I was like, this is not a safe place for me.

AA: I did not know that.

SH: Yeah. And I told them, this was so juicy. But I just, full disclosure, they asked me to come back and do things with it. And I was like, “Is this a safe place where I can, if someone is treating me poorly, will there be a way for me to be safe here?” And they were like, “Oh, sorry.”

AA: No one stood up for you?

SH: And then when one of the ladies left they called me and they were like, “It should be a safer place now.”

AA: No way.

SH: Yeah. So for me, we talk about what’s legal and what’s not, and unfortunately, what’s legal doesn’t mean anything. Because at the end of the day I could still be hurt, I could still lose my job, I could still be villainized and the ramifications that come with that. And then the situation of Emmett Till killed. Most of the mistreatment I’ve experienced was at the hands of white women. Especially in a professional setting, which is wild.

AA: I am so, so sad to hear that. I do want to pause here for a minute and ask you, I would imagine it would be hard to not have that color in your perception. And you can say it does.

Most of the mistreatment I’ve experienced was at the hands of white women. Especially in a professional setting…

SH: Oh yeah. My experiences, of course. But I’m very fortunate and I also have a lot of amazing white women in my life who, seriously, I know would go to bat for me. And I even have times where I talk to friends that I worked with, and this is probably really interesting because I talk to friends that I worked with, white women, at that place I worked at. And they were oblivious and shocked and they didn’t want me to experience that. And I did harbor some resentment for a while about how they didn’t stand up for me or come to bat for me. And you know what helped me, was realizing that they were experiencing sexism and I didn’t stand up or come to bat for them. And I was like, why not? And I looked at my lack of awareness. I wasn’t experiencing it. And so it gave me a lot of sympathy to realize it was more complex than I realized.

AA: There’s the topic of our conversation right there.

SH: There we go. Wow. I didn’t already talk about this, did I?

AA: No, no, I did not notice. Oh my gosh. But this is the conversation. Like we said with bell hooks saying that white women and Black men are sometimes the oppressed and sometimes the oppressors. And this is what we talk about. What are our blind spots? And we can have the humility and the strength to be able to be like, “No, really, I want you to tell me.” And then be able to hear it and acknowledge them and learn, and make changes if we need to make changes. But that’s hard.

SH: And at the same time, I’m like, I was mistreated and I was also a part of a system that mistreated women. I was also a part of that. And that is so embarrassing and so shameful to claim, but I also feel like it’s really important. Because in this world, at a time when we’re trying so hard to be like “No, I’m right.” We have to sit with this.

AA: Yeah. And that’s how I feel too, in the ways that I still experience privilege too. Reading these accounts of what was happening to these people that my racial group was doing, it’s horrible, the guilt and the shame that comes up that I need to process and work through. And the privilege that I experience where, like you said, I might not even be aware of what other people are experiencing, but that’s why these conversations are so important.

SH: And once again, like we talked about with Ella Baker criticizing Martin Luther King, it’s not about who’s good or bad, right or wrong. It’s about sitting with nuance and being able to sit with your own crap, I think, and ask how we are figuring into systems. And it’s not enough, and I believe our friend Letha talks a ton about this, it’s not enough to be like, “I’m going to change the world by doing this movement.” You have to sit with your own stuff. I have to sit with the fact that I was participating in sexist organizations and systems.

AA: Yeah. And me with racist ones, too.

SH: Oof.

AA: Oof.

SH: Look at us.

AA: Look at us! Unpacking it all. I would say that there are many factors to this, but two more factors that I identified again in the journals that were written by these people, this isn’t just me guessing, but Black women talked about white-centric beauty standards and how that impacted them. That in the media, in commercials, everywhere you went, even colorism within the Black community, that it was always like “better” to have fairer skin or to have straighter hair. And so coming together with white women as a twenty-something-year-old, and they were mostly with Black men, there were some white men, but it was deeply wounding to these young Black women when Black men would choose to date white women. And Black women would talk about, like, “We’re perceived as strong, almost androgynous. Like we’re not real women because we’re so strong and we’ve always had to work and we’re super hard workers. And there’s this myth of matriarchy.” And so Black men would be like, “Oh, I totally respect you, but I would never date you.” And they would date white women instead. And this was a huge source of pain. Does that resonate at all?

SH: I hear that still to this day.

AA: Really?

SH: Yeah. I mean, especially the effect of Eurocentric beauty standards and how Black people often do not genetically fall into those standards and it affects everyone. And I think you mentioned it in your paper – book?

AA: Paper.

SH: Your academic brilliance, where a Black woman with a white man was not seen in the same regard because white men have always claimed everything. But Black men being with white women was where it really threw things off. And you hear a lot of things in the Black community, about how it feels like there are so few strong Black men that when they do marry a white woman, it’s like, what about Black women who are fighting for their lives out there, showing up boldly, very strong people. And then once again, it’s like that pedestal that black women can take anything, they can handle anything. And it sometimes almost feels like an excuse to make their burden heavier in some senses. But yeah, you see that a lot. I mean, my brother came under fire in high school for dating a white woman, but it was also the fear of like, what if she claims anything? You’re automatically in danger. And then we see that example because it would enrage white men to see Black men and white women together. And it made it so dangerous, not just dangerous for the Black men, but also felt like a slight to Black women. It was just adding on that Black women couldn’t win. And it’s no one’s fault to like who they like and love who they love, but there is a complex history behind it.

AA: Yeah. That’s so interesting that you still see that.

SH: Oh, yeah. Quick Google search, like sometimes they give celebrities a hard time. Do you remember Sister, Sister?

AA: Yeah.

SH: Two Black twins separated at birth in that show, it’s Tia and Tamera Mowry. One of them married a white man and I guess she was given a hard time for that. But it doesn’t come close to a hard time given to Black men for marrying white women. And whether it’s valid or not, which seems weird to even say, that is what you see.

AA: Well, and like you said, there are deep historical roots to this. Because like you said, white men had claim on Black women’s bodies from the time of enslavement. But then I guess the pedestalization of the white woman comes from patriarchy. Because it’s the white man saying she’s an angel, she’s delicate, she’s untouchable. So yes, don’t treat her as an equal, but we have to protect her.

SH: Isolate her…

AA: Yes, exactly. But then the racist trope of the Black man who wants to–

SH: The animal that wants to ravage–

AA: Yes. Take his property. And she’s like this pure virgin property. And that’s why a white woman–

SH: Ew property.

AA: Yeah. But that’s why the white woman can wield that. And we talk about her having access to the forces of white supremacy, like you just mentioned with Christian Cooper and Amy Cooper in Central Park. All she has to say is that a Black man is threatening her and the structural forces of white supremacy, she can just be a damsel in distress and then everybody comes to her. So that dynamic was very much at play in the ‘60s in SNCC. And because they’re in rural Mississippi, where the KKK reigned.

SH: Pervasive. Every aspect of government, law enforcement.

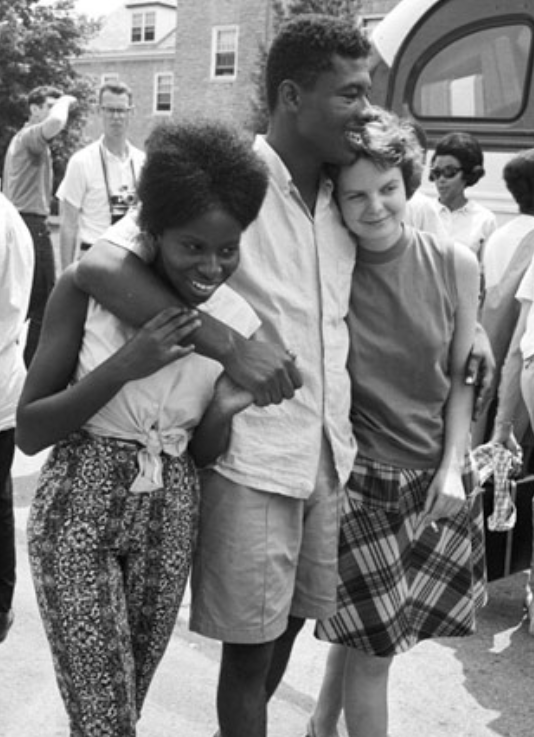

AA: Yes, and they were encountering these people all the time. So this was contributing to fissures too, because like we were saying, these are young people who are dating each other. And you get situations, I’m thinking of a specific couple, a Black man and a white woman dating, and he doesn’t want to acknowledge that he’s dating a white woman. Sometimes it was like a badge of honor.

SH: This is in the civil rights movement?

AA: Yes, this is in SNCC. Sometimes it’s a badge of honor to date a white woman. But sometimes it was like, “Ugh, I’m not supposed to be,” or it would diminish his reputation. So sometimes he would pretend he didn’t know her in the daytime, basically during the day when they’re with their friends, their co-volunteers in SNCC, he would pretend he didn’t know her, and then they would get together at night. He’s coming to that from all of the historical context that he’s coming from as a Black man, she’s coming, and this is a specific couple I’m thinking of, she’s a Northern white woman. She’s coming to it like, “You’re going to sleep with me and then pretend you don’t know me? You’re sexist.” Is there a little bit of sexism there? Maybe. But you can see how these two different people are approaching it.

SH: And their experiences are so valid.

AA: Yeah, I guess so. Yes.

SH: Of course she feels that way. Who wouldn’t feel that way? Especially without knowing–

AA: He’s using her. Right. And I should say too, there were strict rules that you were not supposed to date each other, and even showing interracial affection, especially a Black man with a white woman. I mean, white women endangered Black men anywhere they went. In fact, white women were told that if they had to ride in a desegregated car with your buddies, white women needed to lay down on the floor of the car with blankets over them because if there was a KKK member policeman who saw a Black man with a white woman, he pulls him over and that Black guy can disappear.

SH: Oh goodness. There’s a story that I read in your paper, where he talks about– who was in jail?

AA: Charles Sherrod.

SH: He was in jail, a Black man in jail.

AA: For demonstrating. Again, he was just a SNCC guy who was at a demonstration.

SH: And they’d never physically hurt him, but they did have him in jail, and one day the guards came in and just beat him up, right?

AA: Yep.

SH: And he was like, “What is going on?” Then a guard came in later when he was recovering and kicked him in the stomach or head and said, “That’s what you get, you son-of-a-B, for trying to marry a white woman.” And he was like, “What?” And he found out later that one of his compatriots, who was a white woman, thought that she could get more access to him if she just told them she was his wife.

AA: Because they wanted to visit.

SH: And support him, and it in fact just endangered him.

AA: Exactly.

SH: And he still has those scars, I think later he was talking about it. That’s wild.

AA: Yep. So again, these white women who are approaching it, she thought she was doing something nice by visiting him in jail and they were good friends. And she got him terribly beaten. This happened a lot.

SH: I would never be like, “What a bad idea.” But the result… Oh my gosh.

AA: Yeah. And it was on her to know that, because they did train these kids. They did train these people and it was called the “anti-lynching code.” You’re not allowed to date because you can get your best friend or your boyfriend that you really love, you can get him killed. Just these well-meaning but misguided and uninformed things.

SH: The tensions of Black men and their lived experience coming into this creating tensions with white women and their lived experience, and then Black women, I can see how these fissures are created.

AA: Yes, exactly.

“That’s what you get, you son-of-a-B, for trying to marry a white woman.”

SH: There’s a point, did it come to that?

AA: That’s where we get to Waveland. And I’ll just add one thing about what white women were bringing, and I kind of implied this earlier, a lot of these white women were coming from the North. Some were Southern, and I will say Casey Hayden is one to look up if you want. She was a real hero, an anti-racist white woman who really got it.

SH: Is she from the South?

AA: She’s from the South, she’s Texan, so she grew up in segregation. She understood the codes of the South. And she said, like, “I took jobs behind the scenes at SNCC. I did office work. If I was ever in a situation where I was with Black men, I was under a blanket so nobody could see me.” She would never, ever endanger her fellow SNCC workers. But a lot of white women came in later for what was called Freedom Summer, and so they hadn’t had the time to train.

SH: Sounds like a good time. Like, “Yo, some people are going to Cancun. I’m going to Freedom Summer!”

AA: Yeah, yeah. Well there were a lot, and a lot that came from Stanford and from the Ivies on the East coast. Really wonderful white people, a huge group of white people came down for Freedom Summer to do voter registration. Because there were a lot of counties, especially in Mississippi, Stacey, it made me cry. Lowndes County in Mississippi was 80% Black, and guess how many Black citizens were registered to vote in 1964? It was 80% Black. Zero.

SH: Zero?

AA: Zero people.

SH: I feel like you’d see the effects of that today.

AA: You do. The voter suppression was so bad that these SNCC volunteers just needed more people and they would go door-to-door, like Mormon missionaries, and say, “Are you registered to vote?” So many of them did not even know they had the right to vote. It was so badly suppressed for so many generations, they didn’t know they had the right to vote. So they needed SNCC volunteers to register people to vote, that was one of their big initiatives. They recruited and they debated whether they wanted to bring a bunch of white kids in. It was already debated.

SH: For the same reasons.

AA: Yes, for the exact reasons we’re talking about. So a bunch of white people came down. One detail that was very touching to me was that of the, I think they had about a thousand college students come down, a thousand white volunteers flooding into SNCC, half of them were Jewish.

SH: Oh.

AA: Of those white volunteers.

SH: Why? Why do you think that is?

AA: That was my question. And then I suddenly realized that it had only been 15 years since the Holocaust.

SH: Like that generational, inheriting that fine china of oppression.

AA: Yes. Mobilized to help others. Isn’t that beautiful?

SH: That is.

AA: And if you look at the mentors of SNCC, too, a lot of them were rabbis. So there was a hugely outsized number of Jewish participation in the civil rights movement. I think the United States was like 2% Jewish and yet half the white SNCC volunteers were Jewish. Isn’t that beautiful?

SH: Go off, I love that. Showing up.

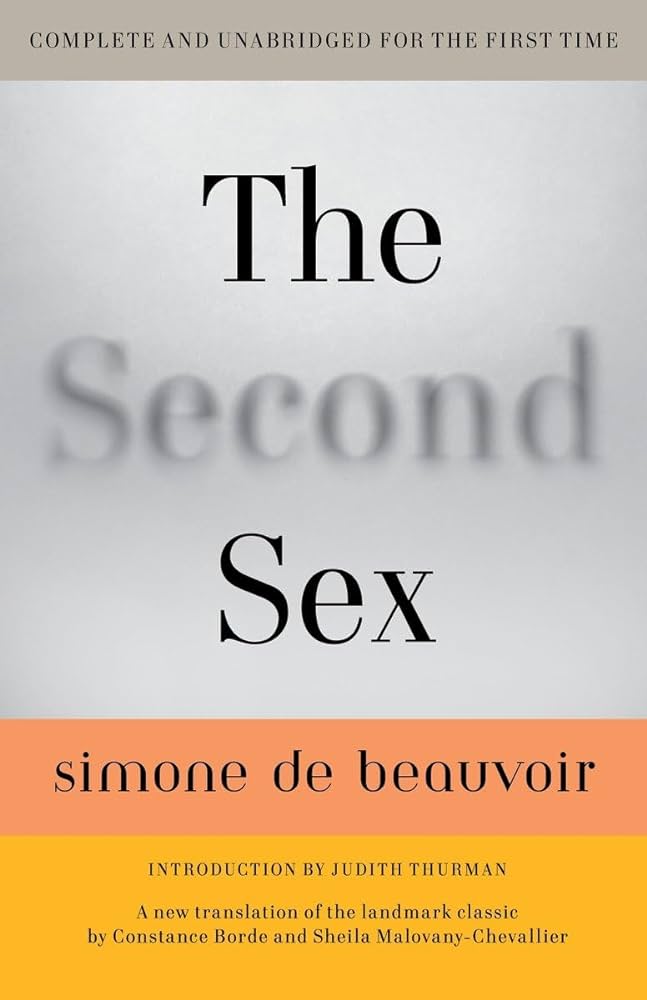

AA: Yeah, they showed up. But white women were also bringing, I mentioned those two books earlier, two books that had changed the world at least for Northern white women. That was The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir, that had been written in 1949 and published in the early ‘50s, and The Feminine Mystique came out around the time that SNCC was forming also.

SH: Interesting.

AA: Actually, The Feminine Mystique came out in ‘63 I think. But by Freedom Summer with all these white women, a lot of them had gone to Harvard, a lot of them had experienced terrible sexism. And they had read these feminist works that had just hit the scene and were causing a huge feminist awakening among white women. So they’re coming into SNCC and into their civil rights work already–

SH: Sitting in it. Stewing in it, ready for something to change.

AA: Ready for something to change. And they had the lenses on from having read feminist philosophy of like, “That’s not fair. That’s sexist. How dare you treat me like that?” to men.

SH: And where better to make a difference than in the place that’s championing equality.

AA: That’s a great way of looking at it, and it is. And for a place like SNCC, that claimed to be egalitarian and claimed to have a flat democratic structure, there’s no hierarchy. That would be the way to do it in the place where you could do it. And they did say that that was true. Of all of the organizations that existed at the time in the early sixties, that was the safest place to do it. However, here’s the thing that brings us to the conference, where the cracks are really starting to widen. We already talked about what Black women are bringing and what Black men are bringing. Women are bringing this feminist consciousness. And if you think about it, for a white woman specifically from the North, but I guess any white woman, her biggest pain point is sexism. And of course she cares enough about racism to enter the civil rights movement, but she doesn’t have personal experience with it. She hasn’t had to protect any of the men in her life. She can criticize her dad for sexism without worrying that he’ll get lynched. No white woman has ever had to fear for the men in her family, and so these white women are a little bit ignorant of what it means to criticize men. If you grow up in your life where, and again I’m thinking of actual accounts, where like “My uncle was lynched.” These Black women had members of their family who this had happened to. And white women, I think, didn’t realize that. So they’re coming in with these lenses of the biggest pain point being feminism, and we are all sisters together. We have our womanhood in common.

SH: Black and white, we’re all in this together.

AA: Right, exactly. So this brings them to Waveland, where, as I said, this paper was written, it was anonymously submitted, nobody knew who did it.

SH: The manifesto… We’re back.

AA: We’re back. We’re back to the manifesto. And I should say there’s way more context, SNCC was already really struggling because of a lot of different political things that were going on. They had thrown in their weight with white allies who said they were going to help them and in the end kind of betrayed them.

SH: Oh no.

AA: So those fissures were about way more than gender.

SH: There’s a lot of history.

AA: There’s a lot of history that we don’t even have time to go into. But they were starting to feel really betrayed by white allies and those well-meaning white volunteers were already causing a lot of problems. So when those women wrote the manifesto, what we have in the record is that they were four white women. And I actually have a copy.

SH: The four women were white.

AA: The four women were white.

SH: So it wasn’t like we got women together of all places, let’s get your voices, get your thoughts.

AA: Exactly. Oh, and one question I had that I never could answer, I looked everywhere, Stacey. And even in my interviews, nobody knew the answer for some reason. Will you find it? I really want to know! I want to know if they asked Black women to participate, because that would make it really different.

SH: That would change things.

AA: It would change everything. But they didn’t. And so the effect of it was that when it was revealed that the authors of the manifesto were all white women–

SH: Because it was anonymous.

AA: It was anonymous. These are quotes, and I’m just going to choose a couple of them. Here are a couple of points from the SNCC position paper. They said: “The SNCC staff was involved in crucial constitutional revisions at the Atlanta staff meeting in October. A large committee was appointed to present revisions to the staff. The committee was all men.” Or it would say, “Although there were women in the Mississippi project who’ve been working as long as some of the men, the leadership group is all men.” And “A fall 1964 personnel and resources report in the Mississippi Projects lists the number of people in each project. The section on Laurel Mississippi lists not the number of persons, but three girls.” So it would say, like, this man with the name, this man, this man, this man, this man by name, and then “three girls.” Or when they would list the name, they would put “(girl)” in parentheses after to designate. They didn’t do that with the men. So it seems to me that there were a lot of quite legitimate grievances that they were not being treated equally. And they compare it to race and the in the manifesto they say…

SH: I could see how all of that would already start being like, “So what side do you take?”

AA: Yeah, for a Black woman to hear that. So they had written “We were starting to feel our Black sisters pull away from us [already before Waveland]. They were pulling away from us. The chasm was starting to grow between us and we were desperate to mend the breach.” So we wrote this manifesto about sexism, and then they were just puzzled. Because the reaction of the Black women when this was read, they expected the Black women to be like “Yeah!” And they were just silent. And after that, again, there were many reasons why SNCC started to dissolve.

SH: Was that the beginning?

AA: Yeah.

SH: This giant iceberg cracking. Because I can almost see Black men and white women, with Black women almost being the swing vote, like this deciding factor in how this will swing. And I remember doing, and you can correct me on this, it was so long ago. When I was doing my undergrad I was doing some PR research, and every now and then we would dive into different elements of race and gender. And when it comes to race, often Black people identify first by their race and then by the rest. Even in the way we talk about it, like I’m not a man who is Black, I’m a Black man. That is integral to my identity. So I can imagine Black women having to decide, “Do you stand with women or Black people?” is almost the question.

AA: And at the time, I mean it just seems so obvious, which was the greater–

SH: Battle.

I can imagine Black women having to decide, “Do you stand with women or Black people?” is almost the question

AA: Yes! Which is the bigger battle priority at the time? It’s obviously race. It’s obviously race.

SH: This isn’t the time to– And it’s so crazy because, like, were they bad grievances? Was this wrong of them to have concerns with those things?

AA: I don’t think it was wrong for them to have those concerns.

SH: I think of Ella Baker. And I don’t know, maybe this isn’t fair, but it seems like Ella Baker knew that it wouldn’t help this so important cause to start inner tensions. Yes. And I don’t even like framing it like that, because it’s not like they were trying to start drama.

AA: No, no, they certainly weren’t. Everything was on the table for discussion. The whole point of having the position papers was to air your grievances so we can talk about it. But they misjudged it. They miscalculated. And here’s a good example, because Ella Baker was Black so she’s in a different position. It’s her dad and her son or her nephew that she’s talking about. She’s in a different position to be able to make those criticisms. Here’s another one. Prathia Hall was at Waveland, she’s a Black woman, she’s young. She was a SNCC worker and she was the daughter of a minister, and she herself was an incredible preacher. And she was, years and years prior, and this will be familiar immediately when I start saying this. She was asked to give the closing prayer, but it kind of turned into a sermon, and the church had been burned down. It was a huge gathering room, this church had been burned down, and young Prathia Hall goes to the front, this Black minister’s daughter, and she starts preaching. And she starts saying, “I have a dream that–” and then she continues and then repeats the phrase, “I have a dream.” Repeats the phrase “I have a dream.” Yep. And Dr. King was in the audience that day in the congregation. This is before the March on Washington. So to your point about Black women having to make choices, she said that he acknowledged privately to her that he got that idea from her sermon, but he never credited her.

SH: You held onto that plot twist. Whoa.

AA: Yeah, he never credited her publicly. And she just said, “It’s okay, he asked me–” I don’t know if she said he asked her for permission, but he kind of acknowledged that he got that idea from her sermon. But he never credited her publicly and she chose to graciously say, “You know what? This is for the greater good. This is a movement that’s bigger than me.” And Prathia Hall was at Waveland when this position paper was read.

SH: Wow.

AA: Where these white women were like, “You put (girl) after our names and you formed a committee without us and didn’t even ask us.” And so these Black women are like, “Yeah… Why is this the priority right now?”

SH: Oh, that’s tough.

AA: Yeah, it’s tough. It’s tough.

SH: Sorry, just the nuances of sitting with it. Because of course they’re not invalid, their experiences aren’t invalid. That is so valid to feel that, to want that change, but when you look at the strategy or the goal or the focus. Oh, that’s tough.

AA: Yeah, it’s tough. And they do say in the paper later, they make the comparison that they’re both caste systems. The patriarchal caste system privileges men over women, just like the race caste system privileges white over Black. Like, “You don’t like being called ‘boy’ by a white man,” this is in the paper, “We don’t like being called ‘girl’ by men.”

SH: Hm. Interesting.

AA: So they make this one-to-one comparison that sexism is like racism, and they say it’s every bit as painful.

SH: I could see the strategy of speaking to something that you really understand, and I also see that it feels like they’ve just pinned it against each other comparing the two.

AA: Right. So then to take it through to today, SNCC, the Black and white together, it was so utopian and so beautiful but they schism. And so Stokely Carmichael with Black Power, SNCC basically breaks apart. And you get these heart-wrenching accounts of people who are best, best friends who don’t speak to each other for decades.

SH: Oh wow.

AA: People who were dating and loved each other don’t speak to each other for decades. It is a huge breach. A huge breach. And again, I’m not saying it was all because of the Waveland paper, but the Waveland paper did not help. It really did backfire. Then in SNCC, you have the Black workers saying to white people, “Go North and fight your own oppressors,” in those exact words. They dismissed all of the white workers from SNCC, just sent them back North. All of them. There were no white people allowed in SNCC. After that they allowed the Zellners, they were this older white couple that they allowed to stay on.

SH: Like, they’re cool though.

AA: Yeah. And with Casey Hayden, one of the guys said to her, “When we said white people should leave and fight your own oppressors, we didn’t mean you, Casey.”

SH: So it was noticeable that she was showing up differently.

AA: She was showing up differently. But she was one of the authors of the paper.

SH: What a plot twist!

AA: So you see her–

SH: They should make an HBO show, Amy.

AA: I think it’s so interesting! I’m so glad you think it’s interesting.

SH: Yeah, it’s so complex, it’s so nuanced. Juicy.

AA: Juicy.

SH: That would be a big end-of-season reveal.

AA: Yeah. So there you do see all of these women reacting very differently. And I followed each of these white authors to see how they talked about it afterwards, and some of them kind of doubled down on it and they’re like, “No, it was a big problem.” You can see Casey like, “I don’t even really remember writing that paper.” Which I think she didn’t, because it really did not get any attention at first. I think it was maybe awkward for a little while, but then she really tried to do repair work afterwards. But they all did go to the North and they started fighting in different ways against poverty and against racism in the North, stuff like that. But more harm was done when, like I said at the beginning, and this kind of wraps up the arc of this part of the story. When these white women historians dug up the paper, this is how I got interested in it, because the first books I found were by white women historians who told that story. There was a sit-in that happened, there was a feminist manifesto that was written, and those Black SNCC men were so sexist that that is what caused the women’s lib movement in the ‘70s. They were telling this story, and I read it and believed it. It was only when I started digging in more that I was like, wait, the more compelling story for me isn’t what happened between women and men. It’s what happened between white women and Black women. Why did that happen?

SH: Because you’d think if it was just a question about sexism, why did Black women stay on board?

AA: Right. And why did they stop speaking to the white women? Why can I not find anything that Black women said? My sources in my paper are from emails much later that were so hurt. So hurt and so angry.

SH: The Black women?

AA: Black women were so hurt by it still and so mad.

SH: It does feel really interesting, even the concept of speaking up for people but not involving people. They almost didn’t acknowledge that there could be different lived experiences.

AA: Yes. And so patronizing for white women to speak universally for “women.” And that’s why I so badly wanted to know, like, did you even ask? You said you were best friends with these Black women, why weren’t they huddled around the typewriter or the mimeograph machine with you? Why do that?

SH: It probably would have gone a little differently.

AA: It would’ve gone so differently. And we might be feeling those differences now. You know what I mean? Because then the history would’ve been written differently. And just that example of white women marching into a situation with The Second Sex under their arm, calling out situations that they don’t really understand, and vilifying men of color who are already so vulnerable in society. And they keep doing it.

SH: To think about if were they right or wrong, did that lead to a movement that has done good? Yeah…

AA: I mean, maybe. Sure. Yes and no.

SH: It feels like, “Were they right or wrong?”, that feels way more simplified, versus “What information were they lacking?” They’re presenting a manifesto about involving more people, really making it egalitarian, and they lacked involving other women.

AA: Right, right.

SH: Which even then feels kind of weird for me to be like, “Well this is how you’re not going about it right.” Oh man.

AA: And to your point, not just involving them, maybe what should have happened– Not maybe, this is where I land on this since now I’m thinking about it. I think what they could have done, because there were some legitimate grievances, is to go… It was a Black-led movement. It was Black and white together. It was a Black-led movement. So they should have gone to Ella Baker, or Prathia Hall, or Ruby Doris Smith. Or all of these women, Muriel Tillinghast, they could have gone to Gwendolyn Robinson, so many Black women who would’ve been like, “Yeah, that is a problem.” And then they could have said, “Do you think this is a priority that we should talk about?” and then followed their lead. That’s what I think should have happened instead, like, we are the supporters here, we are guests here. It’s actually not our role.

SH: Renovating the house and that we’re a guest in. I guess my question for you is, how is that relevant to us now? How do we take what happened there and apply it to us these days?

AA: Well, that’s my big takeaway. My big takeaway after this paper is to know when you’re in a supporting role. You know what I mean? And when I did season three of the podcast last year, over and over and over again, no matter where I was interviewing women, whether it was in the Middle East or Africa, or South America or Asia. No matter where it was, people were very nice to me, but there was a big dose of skepticism. Like, “Yeah, I’ll do the episode, but what’s your goal here?” Because my podcast is called Breaking Down Patriarchy. Are you just another white feminist who’s going to come in here and criticize Arab men because Arab women are so oppressed? Are you going to come in here and talk bad about my husband, my uncle, by talking about machismo, you white woman who doesn’t understand what it is to live here and be oppressed. You know what I mean? There is still that tension. I have to come in, and this is what I learned, is that I am here for you to teach me. Let me know how I can be a support to you. I’m an expert in white Mormon feminism because that’s what I know about, and I do that gently and carefully too, because a lot of people I love are white Mormon men. So I know the nuances of that, I care, I have a vested interest in that community. That’s the only context, in my opinion, in which I could be a leader and I actually know what I’m talking about. In every other context, I come in and say, “Is there anything I could do to help you?” And I don’t have the right, or I’m in no place to make any judgments in other contexts. That’s what I think. What about you? What are some points?