“How do I love this person and still help them break free?“

Amy is joined by adrienne maree brown to discuss her latest book, Loving Corrections, and learn about improving our accountability practices, plus what it takes to live in right relationship with the friends and family with whom we most disagree.

Our Guest

adrienne maree brown

adrienne maree brown (she/they) is growing a garden of healing ideas. Informed by decades of movement facilitation, somatics, science fiction scholarship and doula work, adrienne has nurtured Emergent Strategy, Pleasure Activism, Radical Imagination and Loving Correction as ideas and practices for transformation. adrienne is the NYT-bestselling author/editor of several published texts, a ritual singer-songwriter, co-generator of the Lineages of Change Tarot Deck, and co-creator/host of How to Survive the End of the World podcast with Autumn Brown. adrienne’s latest book Loving Corrections is now available from AK Press.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: I’d like to begin today’s episode with a couple of questions. “If we understand that we cannot cancel other living beings from the world, then how do we find dignified ways of being in communities that face, address, and evolve beyond harmful patterns? If we can accept that each of us has some responsibility for holding the massive changes needed for our survival, then how do we hold each other close enough to learn our hardest lessons?” These are just two of many insightful questions that the author adrienne maree brown asks at the outset of their most recent book, Loving Corrections. These are questions that I’ve asked myself as well. Long-time listeners know that part of the core mission of breaking down patriarchy is to deconstruct patriarchy intelligently and compassionately, being hard on systems, but soft on people. So, I was so excited to discover this book, which talks about living in right relationship with one another and how even across wildly divergent bubbles of information, we can still honor each other’s humanity, and we can still learn from each other and cultivate compassion, justice, and love. To talk about all of these things today is the author of Loving Corrections, adrienne maree brown. Welcome, adrienne!

adrienne maree brown: Hi, Amy. Thanks for having me.

AA: I am so excited for this conversation today. adrienne maree brown – she/they, are their pronouns – is growing a garden of healing ideas. Informed by 27 years of movement facilitation, somatics, science fiction scholarship, and doula work, adrienne has nurtured emergent strategy, pleasure activism, radical imagination, and loving correction as ideas and practices for transformation. adrienne is The New York Times bestselling author and editor of several published texts, a ritual singer, songwriter, a co-generator of The Lineages of Change Tarot Deck, and co-creator and host of the How to Survive the End of the World podcast with Autumn Brown. adrienne’s latest book, Loving Corrections, is now available from AK Press, and that’s the book that we’re going to be discussing today. That’s the official bio, adrienne, and now maybe we can start by having you tell us a little bit about yourself, where you’re from, and what brought you to do the work that you do today.

amb: Well, I was born into a family that was rooted in the Deep South. Both of my parents were born in South Carolina and my dad joined the military, and so I grew up moving around in a very male-oriented and -centered landscape. I think my mom and my dad, they were rebellious to a certain degree as an interracial couple, you know, they knew that they wanted to do things differently than what they had grown up seeing normalized, but I think that gender was a slower shift than race for both of them. And I think having three daughters, even our dog was a girl, I think growing up with that set-up in the household really created some shifts over time. I went to college in New York, I always said I came of age there, and I’m really grateful. I had time and space to be there where there were so many ways that people carried identity and culture. And it helped me to understand, in addition to growing up having been around the world, it was just like, there are so many ways to do this. And what matters most is that everyone has dignity and agency in how they’re choosing to live into identity, be it gender, be it race, be it ethnicity, religion, et cetera, sexuality, of course. Yeah, that’s a little bit more about where I enter.

I’m very interested in love-based organizing and love-based work. So when I come across a system that feels like it doesn’t love me or love the people that are participating in it, that’s where my antennae go up and I start doing my scientific method and experimenting and trying to figure out what would have to shift. And all those years of facilitation and observing people and holding people, being a doula, all of that, it really has shaped my worldview where I’m like, “Oh, everybody needs to transform. Everybody needs to cross some thresholds in their lives and everyone needs help to do that.” So that’s a little bit more. And I recently returned back to the South– or it feels recent, but about three years ago, I moved back down South, never thinking that I would live as an adult down here, but it feels like home and feeling home feels really important right now. Finding land that you can love and that wants to love you back feels really important to me right now.

AA: That’s beautiful. Thank you for that introduction. I’m wondering, as I’m thinking about your professional bio and the published texts that you’ve done, all of the work that you’ve contributed to the world already, why the need to write this book particularly, Loving Corrections?

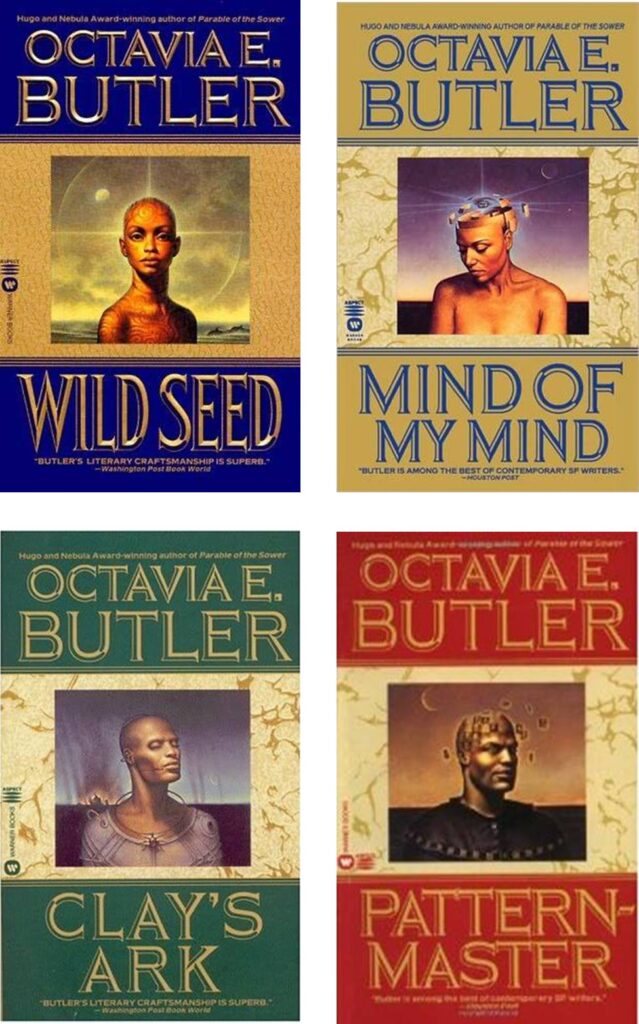

amb: Well, one of my favorite authors is Octavia Butler, and one of her series she actually wrote backwards. She wrote Patternmaster first, and then she was like, “Well, let me pull the thread. How would we get there? And then how would we get there?” So she ended up writing the set of four books backwards. And I felt a little similarly about coming to this book because I feel like Emergent Strategy, you know, I introduced it at the framework of Transformative Justice as I was learning it and practicing with it in that book, and then I kept pulling that thread and it keeps being a place where people are like, “Okay, but how do we actually do it?” So Holding Change was a book that I wrote that was how to facilitate. So, Emergent Strategy was like, here’s a framework on being in right relationship with the world, which means being in right relationship with change and learning from nature and reclaiming our nature and like all these things. Holding Change was like, “Okay, so you got that framework. Here’s how you actually facilitate space and mediate space from that place.”

Then We Will Not Cancel Us was like, “Let me try to go more directly, straight up.” The thing I keep seeing happen, which is that we’re all really frustrated, angry, hurt by these systems of oppression that often function through identity and they’re designed to make us feel less than, and designed to make us turn on each other, so we’re trying to break ourselves out of these systems. And for some reason in this moment in history, the main way we’re doing that is by tearing each other apart and just being like, “I see this system in you, know that I see this system in you,” and just tearing each other apart and very publicly trying to assert our dominance over each other. And I was really like, as someone who’s been in movement and who sees the most beautiful potential for humans, how can I dive into this moment and offer something that feels like, “What would love say? And what would the mushrooms say?” Mushrooms are like, “Listen, we can compost anything. If you think it’s toxic, spill it over here and we will process that into something edible,” you know? So I was like, “Okay, what do we need to learn?” And so that led to We Will Not Cancel Us. And still people are like, “But what about with my dad? What about with my friend who hurt my feelings? What about with this person who agrees with me on every single issue, except Israel. What about this person? What about that?” And people were coming with these very specific questions, which I heard as, “How do I love this person and still help them break free from the system that is holding them, even though I’m still breaking free from these systems?” So this book kind of came together organically. I realized that I was answering those questions one at a time.

The first essay, which is about relinquishing the patriarchy, was originally, I wrote that, I think in 2019. I wrote ‘A word for white people’ in 2018 or 2019. Some of the pieces were, like, I had been writing it and people had been sharing it with each other and being like, “Okay, here’s something useful.” And then I had been writing this column for YES! Magazine where I was really deep-diving into accountability because something that’s always been a concern to me is how do I stop pointing outward and start really taking accountability and saying, “If I can’t change this in me, I can’t demand it from anyone else.” I really have to be willing to be rigorous about my own accountability. And it all came together as like, this text, all these interventions, these loving interventions by identity or by focus are connected to this bigger arc of accountability that I’m developing. So I got really excited when that clicked and I was like, this is Loving Corrections. This is the thing that I do as a facilitator, as a mediator, as a doula. It’s like, “We’re going to hold hands. I’m not letting go of you. We may need new boundaries, we may need to have some hard conversations, but we can still be on this earth together and I can still respect you even if we hold this difference and even if you’re ahead or behind me in your analytical development,” which is a lot of what’s happening.

And then working with my publisher, the timing landed as an August release date for this election season and this year and this moment. And I’m really grateful that this is the text I have out right now because I got to tour it, and I had some sense of what was coming with this election from that touring process. Because people, inside their familial structures, people who want things to change are feeling like the minority. And we have let go of being in some of those hard conversations with our families. I think that’s how we end up here. A lot of what I think is happening is that men who are not able to win the dinner table conversation are trying to legislate it. Right?

AA: Oh my gosh. Wow. Yeah.

amb: Like, “I can’t make my kids not be gay or trans, I can’t make my daughters not have abortions. I can’t make this, I can’t make that. No one’s respecting me. No one’s treating me like the boss and the head of the household by default anymore. I’m taking it to Congress.” You know what I mean?

AA: Yes.

amb: No one gives up power just like that. We have to recognize that for some people, their whole identity is power over. And what we’re trying to offer them is belonging with. I think we’re in a long journey of change. And I don’t think we’re losing, I think we always win and it’s an inevitable thing because humans want to be free and connected, but I do think we have some massive hurdles.

men who are not able to win the dinner table conversation are trying to legislate it

AA: For sure. Wow. Yeah. That just blew my mind. I think that’s really true. And I agree with you. The two steps forward and then big steps back.

amb: Mudslides back.

AA: Mudslides back. But we’re not giving up. You’re making me really emotional just hearing you talk, adrienne. I just think the message is timeless and will be needed forever. But it is so, so of the moment right now and I think on so many people’s minds, like, “What can I do?” And like you said, this is actually something that I say too sometimes. Sometimes I get into theory, and I’m a historian so it’s really useful and helpful to see these big chronological timelines and, “Oh, this is when this happened. This is when this happened.” And understanding how to deconstruct systems. But then when it comes to my dad or when it comes to a really good friend of mine, then it hurts and then it’s tangly inside–

amb: And it feels very personal.

AA: Yes. And then how to hold what bell hooks talks about, fierce love and fierce accountability, right?

amb: That’s right.

AA: And how to hold both. Oh, that is the rub, right? Is when it’s with people we’re in relationship with. So that’ll be my next question for you. You talk about right relationship. That’s a concept that I’ve been introduced to from Native American writings and ways of knowing. Can you talk about that? What is right relationship? And then maybe give some examples of what it is not. What’s an example of what it would be and what it doesn’t look like?

amb: That’s right. I also came across this because I was doing work in collaboration with Indigenous communities and there just started to be a way, as I was listening to the world view, to this idea of the cycle of time and the relationships, the idea that everything that is around us is something we are in relationship to. And that we are out of balance right now, the way the West is developing our relationship with the world is out of balance. It’s all extractive, it’s all control, and it’s all monopolizing the world, colonizing the world, trying to make it all the same world that belongs to one person or a small group of people. So it’s actually anti-Earth, you know, Earth is a biodivergent place that thrives in biodiversity. It thrives in lots of ways of being coexisting. And so right relationship, this idea that actually everything around me is something that I can get into right relationship with. I struggled with whether you use the word “right” in the book because people are like, “right and wrong is a binary” and blah, blah, blah, but I do think that there was a need to claim the space of like, we actually do know when a relationship feels right. It feels fair, we’re both in our dignity, everyone can express themselves, no one’s needs are placed over anyone else’s fundamental needs.

And when you start to examine right relationship, I think it’s one of the most liberating ideas that you can just get a taste of, and all of a sudden it’s like, “Whoa, this is a really different lens through which to view the world.” Because then all of a sudden you’re like, “Why is it okay with me that that person is homeless on the street and that I can drive by them? How would I be in right relationship with poverty in my community?” And again, it takes it out of the theoretical poverty that exists in the world into like, “I’m in relationship, this is someone in my community. Why am I okay with there not being an indigenous presence on land that I have bought a home on? How would I be in right relationship with the people of this land?” And especially when we get involved, when I start doing international work, I’m always like, “Okay, how do I hold the duality of being in solidarity with these people, and I need to bring that home and also be in right relationship with what is my relationship to the land and the power dynamics and the colonial impacts and history and present and all that?” It just starts to feel like I have so much agency in the work of creating right relationship. And then you can also say that if everything is a relationship that can be overwhelming. How do I identify the relationships that are most meaningful to me in this time that I can really tune into? And the ones where I feel like I can make the most change? I was reflecting on this. My family has been going through a period where there’s a lot of medical stuff going on, you know, aging and all that. And my interracial family is coming together, coming towards each other in a way that has taken five decades.

AA: Oh, wow.

amb: It wasn’t just like, “Well, my parents are married.” No, first it was “we’re disowned.” Then it’s like two worlds apart. My parents are always traveling somewhere else. It’s been beautiful to watch my parents keep choosing family and keep choosing to return home, and processing the challenges of it and then choosing to continue. And to keep loving these people and finding like, “Okay, this isn’t an ideal relationship,” or “I don’t really like how this person spoke to me” or whatever, “But I love them and I’m going to show up for them.” And now that they, my parents have moved back South, that was only possible because of all that relationship building over decades. And now the idea that the families are starting to know each other and care about each other, I mean, it’s remarkable. And I raised that because relationships take time and investment over a long period of time, and I think that when we think about changing the world, we think we can set our family over in some little cave of, “You guys just stay there. I don’t feel like yelling at you anymore, but I’m going to go march in the street and be so compelling that everyone else will change, and somehow that’ll trickle down to you.”

And I understand where that comes from. I understand very intimately wanting to be, you know, this is too hard. And sometimes you do have to take a long boundary. I’ve had to have decades where I was out of touch with family members over homophobia and other things, but I learned from my parents that practice of returning home. Ursula Le Guin wrote in one of her novels, The Dispossessed, that the true journey is return. I think that that’s what’s happening to all of us right now, in whatever way, wherever your awakening is happening, it might be like, “I need to return home to Earth. I need to return home to family. I need to return home to community. I need to return home to the offline world. I need to return home to real friendship. I need to return home to accountability with my values.” But there’s something about returning to ourselves that is happening right now. It is emotional. I find myself frequently moved to tears and moved to just gasping, I can’t believe where we’ve gotten ourselves to and how far the path home feels and how willing I feel to crawl if it takes crawling. But it is a very humbling, clarifying moment around what right relationship needs to be for us.

AA: If I can share one thing from my personal life that I wasn’t planning to, but I can relate so much to this. I grew up in a context of Mormonism. I was born in Utah. My ancestors colonized Utah, they were the Mormon pioneers that walked across the plains, but I wasn’t raised here. I was born here and was raised elsewhere, and then went to college at BYU. But then I lived, I mean, the majority of my adult life was in the Bay Area in California and in a very different setting. And I never thought that I would move back to Utah. I never wanted to. And it’s a long story why we did, but we brought our family, I mean, my husband and I moved back to Utah, and it’s been stunning to me to have a lot of things come up that I did not know were inside of me. I think I kind of distanced myself from like, yes, that’s my heritage, but I didn’t want to look at a lot of things about it and I just don’t want to participate in Mormon feminism. And then coming back here, I’m like, oh, I have a lot of work, a lot of reparations to make for my ancestors, a lot of work that I can do, and this is the community I was born into. I have powerful work I can do that’s right here. And I was not expecting it and it’s super uncomfortable, but it feels so right. And yeah, I did not think this is where I would be living and the work I would be doing at this point in my life, but I feel this sense of destiny, almost, and rightness being on this land.

amb: I deeply, I mean, I keep looking around and being like, “This is not a jazz club in Paris. I am so confused.”

AA: Haha!

amb: “What is this? This is not the path I thought I picked.” But yeah, similarly, I got to tour the book around the South and I did a driving tour. So I was driving, and it makes me emotional now to just feel in myself what it means to fall in love with land. And I’ve been really moved watching the resistance in Palestine and watching what’s happening in Lebanon and in the Congo and in Sudan and in Haiti and being like, wow, I wasn’t raised to feel this way about land. Land was something you could let go of and you could be very nomadic and just root wherever you landed like a little dandelion. And I did that really well, but there’s something new emerging in me now that it’s like, “this is my Palestine, this is the land where my ancestors are buried and that means this is where they’re the strongest in terms of their ability to help me.” I believe that. And I don’t know, it does feel like there’s some destiny, and I think we’re not alone. I’ve spoken to so many healers and artists, particularly, who are like, “I feel like I’m being picked up and put where I’m supposed to be by circumstances that feel almost impossible, but somehow it’s all aligning for me to be here.” And to be more still and to have to actually deal with the people I live around. Yeah, it’s a really different way of orienting and I think it’s what we need to do right now.

I also think a lot of us are experiencing the whiplash of like our algorithm online versus reality. And feeling like, “Okay, I think I got way sucked into my algorithm and my bubble was so nice,” or maybe it wasn’t so nice, but whatever bubble it was, it did not prepare me or does not prepare me to be a part of the world. And in the world, people don’t talk to each other this way, and they will not put up with being talked to without respect, without real respect. And also, they’re different. There’s something about that. Oh, you’re you and I’m me. And whatever I feel, my job is not to manipulate you into thinking what I think. My job is to be an irresistible invitation towards what I believe to be liberation, and you can move towards that or not. But if I truly believe what I believe, I need to make sure that there’s room for you inside of my vision because we live on a shared earth. And I didn’t design it this way, you know, I might have done it a little differently where it’s like, if you’re hyper conservative, you go to this planet, if you want to live in free queer magic land, then you can go over here, but here we are.

For whatever reason, the way this earth is designed is that there are people who want to extract all of it immediately and then there are people who want to protect all of it and to listen to it and dance with it. And I’m really curious to see what happens with us as a species. I keep having a real sense of like, our species might not be compatible with earth. And that doesn’t mean it’s a failed experiment, you know, we might not last, there might just be some chicken version of us in the future that doesn’t feel quite as powerful as humans do right now, but I think that would also be okay. For those who are dinosaur scholars, the kids in my life all go through dinosaur phases and at some point they’re like, “Wait, chickens evolve from–?” you know, and I’m like, “Exactly.” Nothing disappears. It just gets the right size, it transforms, it changes into right relationship. It becomes fuel for the next phase. Who knows? We might also become the next fossil fuel and the next chickens and something else. So all things are possible, but in this moment, our job is to look at the world and say, “Okay, I’ve been put here. Who are my people? And how do I treat them really well and keep learning?”

AA: Beautiful. Well, let’s double click on the idea of, like you said, I’d love you to talk about the distinction between accountability versus calling out and kind of policing each other. What’s the difference, and why does it matter?

amb: I’ll start with policing. In this country, I mean, I think there have always been cultures of security and some forms of policing. In this country, our policing system is rooted in the system of enslavement and the system of denying people liberty, and the system of punishment. One of the first major differences is, for me, that accountability is never about punishing someone. It’s about figuring out how to help that person get back into alignment with their own highest self, with their community’s needs. And that might mean that they have to take account for something or they have to be held accountable for something. Because sometimes when we are doing wrong and we’ve been structured in a system that supports us doing wrong, we don’t even realize what we’re doing wrong, or we’re doing it and we’re just like, “The goal in life is to get away with this wrong.” So there’s a lot of healing that has to happen if that’s the framework that we’re in. And I think we’re in a moment like that where there’s a lot of people who don’t really understand the impact of their lives. I think we’re in a really scary place when it comes to the level of educational misdirection and misinformation and just lacking a common ground that we can say, “Oh, everyone at least understands this 12 years of shared information about how the world works and about history.” If I was creating the world anew, I would have groups like Movement Generation create the curriculum by which we learn the management of home and how to be on this planet and with each other.

But we’re not there yet. We’re in this world where any person you speak to might have zero idea how justice works, how the prison system works, how Congress works, how elections work, how any of the systems that are in and around their lives work. And for a lot of people, policing becomes the most common activity like, “Oh, I know that. I see police everywhere, I see what they do, I understand what they do.” And this actually comes to me as well. “I understand how to surveil, I understand how to tell on people.” For those of us who lived through 9/11, you know, the whole city was plastered with “If you see something, say something.” Everyone became part of the police, became a part of this constant surveillance. And if you’re looking through a lens that is tinted with racism, that is tinted with gender phobias, transphobias, then the thing that you’re policing, that’s going to look bad to you, is through this lens that has no real sense of what causes harm and what doesn’t cause harm. We’re not aligned on those things. So I think those are some of the big differences, and I really try to pay attention to where the intention is coming from. I try to really say, if I find myself paying attention, I want to be like, “Why are they doing that? That’s messed up. I need to tell them about themselves.” As a Virgo and as an oldest child, there’s a lot of that in me, haha. I easily could spend a lot of my day telling people how to correct everything. So I think that’s part of why I’ve spent so much time trying to learn to do this with integrity and to create healthy outcomes and healthy relationships.

One of the things I’m always checking for is like, Do I think I’m better than this person? Am I assuming that my way is the right way? Or am I saying that I have had the gift of being informed about something that this person has not received yet, and can I pass this on? Or is this something we actually know, like, we don’t want to have spinach in our teeth, and I see that you have spinach in your teeth, so I’m just going to help you out. And for a lot of these, when I think of the system– Everyone, when I say this, it’s so funny. Everyone does like–

AA: I literally just ate spinach for lunch.

amb: Is it me? Is it literally me?

AA: I trust you’ll tell me.

amb: I will tell you because I’m like, I don’t want to be in relationships where someone would be sitting and not tell me that. So, what do we do if we see systems in your teeth, right? Or instead of “your slip is showing” it’s like the system is showing. So that, to me, is the place where I’m like, “Can I lift this up to you? This way that you’re doing something is out of alignment with what you have articulated that you already know and believe.” And a lot of these pieces are like that, where I’m like, I’m not just writing to any and all men. Generally, I’m writing to men who are like, “I think of myself as a good man.” Okay, you’re the one I want to talk to. White people. “I think of myself as an ally and someone who’s trying to get the language right and show up.” Okay, then I want to talk to you. I want to talk to people who are like, “I care and I am expressing my alignment. I’m expressing that this matters to me.” Then to me, we can have a conversation about accountability because what I’m seeing is out of alignment with what you say matters to you.

Now, there are situations where you don’t have a relationship with someone. I think that’s one of the biggest struggles we’re in right now, is that we see people trying to hold someone accountable with whom they don’t have a relationship. I think that that can work at the level of corporations, at the level of institutions, at the level of government, where you’re like, “As a body, as a collective, we’re saying no to that way that you’re doing leadership.” And I love collective accountability in those practices because they’re structured that way, right? We’re saying, “You have taken on the role of being my pastor or priest or rabbi, you have taken on the role of saying you’re going to be the representative for my political well-being in the world. You have taken it on.” I don’t think it works as well when we are talking about people we’re in relationship with who we’re scared to actually have a confrontation with, so we outsource it to the public.

And I think that’s what happens with a lot of these call-outs now, where it’s like, “This person is a f*cked up boss,” and I’m like, “Okay, what process did you actually go through in community? You have this person’s phone number. What have you done?” And it’s very rare. We like to monsterify people. Most people that you meet are not like oligarchs, monstrous, wealthy, everything right? We’re “us and them”-ing a lot more people into this monster category than I think belong there. And when I talk to people, most of them don’t respond to that kind of punitive exile, but they do respond to someone who sees their humanity and says, “I’ll be in relationship with you for a long time.” And I think we’re in this weird moment right now where there’s a balance we actually need, because some people in these systems are causing so much egregious harm, and we’re trying to figure out what does accountability look like? And I had this talks with folks, friends of mine who work with sexual assault survivors, and it’s complex. A lot of what I want to invite people to do in the book is to relinquish the binary thinking of “this is good, this is bad, this is the only way to do it,” and just lean into the complexity. In real life, in real relationships, there’s complexity. “This person is kind of messed up, but they also are good in this way. This person is a part of our community in this way. This person is kind of messed up and we also know that they struggle with their mental health and here’s some of what happens with it. And how can we love this person? How could we see what they’re bringing to the community? How can we hold them accountable?” So that they can be a part of this community rather than holding them accountable so that they can never be a part of it.

We’re “us and them”-ing a lot more people into this monster category than I think belong there

AA: Yes. Yes, exactly. Oh, this is so beautiful. This is reminding me, actually, of parenting and how I have tried to respond to my children. And that’s something that I try to come home to, is that when someone is hard for me to love, seeing them as a child, seeing them as they were as a child, that really helps me to give the benefit of the doubt and see their divinity, their humanity. That’s what I want for my children. If they make a mistake because they don’t know something yet, or they haven’t been able to develop a tool that they need, then what I want to do is help them gain that tool or help them understand so that next time they can do it better.

amb: Yeah. And then sometimes they’re going to rebel because they’re like, “I need to differentiate myself from you,” or whatever is happening. And it’s like, “I have more positional power, I have more experience, it’s not going to cost me my dignity to let you differentiate and be your own person unless I step away from my dignity, unless I set it down and meet you at age 12 and start a screaming match.” And I really have watched, I mean, I’m surrounded by excellent parents. Really excellent mothers, fathers, I really am grateful that I get to witness, as a non-parent, all the excellent parents. And one of the things I love is that all of them are like, “I’m messing up.” They’re all like, “I don’t know, but I’m doing my best.” I’m like, “That’s the best thing you can offer.” My parents were human beings. They were not up on pedestals doing perfection, they were just loving me and being like, “Okay, you’re changing. We’re all changing. I just had a fit. I’m a human.” Some of the funniest memories and stories we have are of those very human moments that my parents exhibited, where we got to see that sometimes you do get mad and you lose your cool, and you say something you don’t mean, and then the repair and the recovery. I have a memory of my parents punishing me for something when I knew I had done something right, I knew that I had not done something wrong.

AA: You were unjustly punished.

amb: I knew that I was unjustly punished and they were punishing me for it. And then a neighbor who understood what had happened came over and backed my story, basically. So they came in, and I remember it was night and I was already in bed, and they came in and sat down on the edge of the bed and apologized to me. And it’s one of my earliest core memories, being like, “Oh, that’s possible.” Even in this power dynamic with me as like a six year-old, this is possible. Now I look back and I’m like, that was really a precious offering and I didn’t necessarily know it at the time. But the difference between good parents and bad parents is not the never mistaking, it’s not being able to repair and listen to what repair could look like. That’s Aikido, right? The founder of Aikido said that mastery is not that you never fall off the center line, it’s that you recover so quickly that no one can even tell that you fell. You recover and you get really good at that part. And I’m thinking about that now that I’m like, there’s no perfection to offer people about any of this stuff. There’s just being a human who is available for repair and interested in repair and interested in, like, how do we recover our species from what I hope is rock bottom?

AA: Yeah. Let’s hope. I’m reflecting, too, on the mistakes that I’ve made before, and how grateful I am for the grace of other people, for their patience and for their willingness to not exile and cancel me when I’ve made mistakes based on things that I was taught, based on my environment and things I didn’t know yet. And people giving me space to grow enabled me to grow, enabled me to change, enabled me to become an ally where I wouldn’t have been able to, had I been punished.

amb: Exactly. This is part of where I’m able to generate compassion for those that want to be my enemy, that cast themselves as my enemy. I’m like, “You have not had space to grow your soul.” That’s the only way I can explain why you would spend your life and your time fomenting hate, fomenting phobia, fomenting harmful, control-based patterns over other people’s lives. You have not really been held in the arms of true love, love that loves you completely as you are. And you have not been a party to good repair. If you grow up in a punitive world, you think that that’s all there is. And our electoral system functions right now as a punitive device. People are like, “You won, now we won, and we’re going to treat you horribly, now we’re going to win it.” And it’s like, this is how we’re supposed to have our health and take care of our earth, and take care of our babies and take care of our homes, and have homes and make sure everyone’s okay. The whole thing has gotten hijacked away for this other purpose of punishment and control.

Decolonization is going to take us a while, I think, but that’s the way that I understand the work we’re doing right now. Which is like, if I’m not trying to take and monopolize and dominate the whole world with just my way of being, what more becomes possible. And if you can even just ask yourself that question of, “Why am I trying to be in control of everything anyway?” Especially if I can’t even run my household, you know? This has been such a beautiful, humbling process, that accountability work has really made me root into my own life and my own relationships. And suddenly I’m like, there’s plenty to do with just trying to live a life well and be in good relationships with the people around you. Not to be a celebrity and not to take over anybody else’s anything.

AA: Yeah, if we all did that it would fix a lot, right?

amb: It would.

AA: Okay, let’s zero in on gender, specifically. You mentioned that chapter ‘Righting gender,’ righting like R-I-G-H-T for people who are listening, ‘Righting gender, relinquishing the patriarchy.’ And you address this chapter specifically to men and all those who engage in masculinity.

amb: Masculinity, yes.

AA: And you write, I’m going to read one sentence that you wrote. You write, “It is absolutely possible in your lifetime, in a generation, to personally relinquish an unjust ideology, to begin to practice a more evolved way of being.” I’d love for you to talk about that a little bit. How do men dismantle patriarchy and relinquish patriarchy?

amb: Yeah, I think one piece for a lot of the men in my life, and when I was writing this I reached out to women in my life who dated straight, right? Because I was at the time, I mostly date in a queer way. And I was really like, “I’m trying to understand what’s going on with these men.” And I’ll say two things I noticed. One was that men have to be able to understand that the loneliness inside them is not the fault of the woman near them or the women near them. And I think there’s this idea that men are from Mars and they don’t know how to make friends and they only talk about sports. And I think that we let men go so far without having deep emotional connections and then they find themselves in their twenties and thirties getting lonely, being like, “I have more emotions than my network, my community, my workplace, my family, I have more emotions than I can show, or I know how to show any of those places. And it’s creating a deep loneliness or feeling like I can’t be known. No one cares for me in that way.” So I think there’s that level.

And then I think there’s another level, which is that gender is transforming very rapidly in terms of how power gets held. So even though we’re in what I’m calling “the retrograde,” because it feels like everything’s moving backwards right now, but I think it’s more illusion than reality just because so many women are like, “I already know that I’m equal. I know that you’re not superior to me. Even if you change some laws, I just know it.” But we’re in this moment, right, where so many women are coming into that knowledge, which has felt so powerful for us, has felt so disempowering for so many men. And there’s not some model or some perfect way to be like, “Here’s how you do a massive transformation of power.” But I think that what we’re facing right now is a major backlash of people being like, “Listen, my whole socialization and for all the decades, and all the centuries that have led up to this moment, the role that I was meant to play was a natural leadership role. And even if I never ran anything or accomplished anything out in the world, I was going to run this household. That’s my thing. That’s what I do.”

And now to have all these women and queer people, trans people, everyone else coming in and being like, “This is a biodivergent space. We’re all actually equal. Nobody just has a default role of being the head of anything.” We could figure that out. Maybe you do have something, you know, I think there’s some actual real beauty to divine masculinity and divine femininity. I think there is a balance in it again, beyond the binary way of understanding gender, that can really be delicious. I don’t think we attended to the fact that it’s like, if you lose your role, if you lose your sort of given supremacy or superiority, and no one has talked to you about the spiritual work you need to do to be like, “Then how do I find myself?” Then it’s like you’re stripping someone of the identity that they expected to have without replacing it with something compelling. Because it’s not compelling to just be like, “Well, you’re just going to sit at the dinner table and I’m going to tell you you’re an idiot.” I will just say, that’s what I tried to offer to my dad for some time. I was just like, “I went to college and I figured out that you’re an idiot.” And then I was like, “Oh, no, you’re not. You’re a human being and you figured out the very best way to navigate the circumstances you lived in. You actually made some really beautiful sacrifices on my behalf. You love the sh*t out of me and you’re here, you want to be in relationship with me, you just maybe don’t know how. And I’m claiming that I got all this intuitive knowledge or whatever, but I’m not treating you any better.”

So there’s something there, right? The men have to recognize their loneliness, they have to recognize that the power dynamics have shifted, and they have to want something to change. And I think that that can be a really compelling starting point for men that you already are in some relationship with. Where you’re like, “I know that you actually want more.” And then I think that those men have to help other men. I don’t try to go directly to the bros, right? I don’t try to go directly to the furthest down the masculinity path. I know that they’re not going to be able to hear me and I probably won’t be able to hear them that well. But I do go for that sort of lowest-hanging fruit of the self-defined feminist men, men who are like, “I want to be part of movements for social and environmental change. I want to be someone who’s seen as a leader and trustworthy in my community.” Men who are fathers to daughters are also, to me, a low-hanging fruit where I’m like, “You’re already in a relationship with this person who, some part of you recognizes her divinity and her power and how precious she is. So maybe that can help you start to understand yourself in a different way.”

And in the book, I put a bunch of pieces in here that were like, let me give you really clear examples, because I wanted it to get as crystal clear as I could. Because I kept finding that I was talking to women who were like, “Girl, I’m so tired of trying to express this bit by bit, thing by thing, while I’m scared, while I’ve just cleaned the entire house. He doesn’t even realize how much I’m tracking,” all this stuff. So I’m like, “Oh, a lot of conversations aren’t even happening. Women are just like, “This is the best I can get, is light potty training or something,” and it’s like, “No, you can get a fully developed human being.” I think that if you’re going to be with this person and be around them, the goal has to be that you get to be peers for real. In here, there’s recognizing, just as with white people, if you have white privilege, you have to recognize that you have white privilege as a first step. In this it’s that you have to recognize that you are a part of patriarchy, you’re part of a system. And for a lot of men, that first step is the biggest one, because once you recognize that first piece, it’s like, “Oh, okay, I totally believed in this and why, and do I still believe in parts of it? Do I believe that there can be a healthy masculinity that doesn’t have to be expressed through violence or through domination or through inequality?”

And then there’s really specific stuff, you know, really thinking about sharing labor, really noticing places where inequality unfolds organically for a lot of people. One of my favorite ones, which one of my goddesses pointed out to me, was practicing equality in the workplace and really understanding what people are earning. And if you learn that a woman is earning less than you, who should be earning the same amount, you go advocate. And don’t do it as like, “Everyone look at me do this,” just go do it behind closed doors. I always tell people, I’m like, to be an ally means you do the work when none of the people that you’re allying with are around. When you’re in the locker room with the men or when you’re in the barbershop or you’re in the spaces with the men and you hear patriarchy, that’s the place where you get to be like, “Hey.” It’s not even to be like, “Y’all are all wrong.” It’s just like, “I want to offer something else to this conversation. I want to invite us to hold this a little bit differently.”

And there is beautiful work that unfolded after this was published. A lot of men formed small communities and groups and did book clubs. They read the piece together, they created a men’s group where they were just supporting each other to get in touch with their emotions. And there are a lot of men who are actually doing explicit work around this now. That always helps, too, is to be like, you’re not starting this path from scratch. Because that’s also the colonial thought process, right? It’s like, “I must do it all,” right? And then the internet supports that cause it’s like, as soon as you learn something you’re supposed to turn around and be an expert on it immediately. So, you don’t have to be an expert on this. You don’t have to make a TikTok about it. You could just practice. You can be with friends. You can be with a group of men who just say, “I had a feeling. Here’s what it is. Here’s what I’m doing with it. I had an opportunity to make a change in my life, or to talk to my wife or my daughter or my mother or my coworker. Here’s an experience that I had of being able to change my relationship with one of the women in my life, one of the queer people in my life, one of the trans people in my life.” And there’s so much about listening. So listen, listen, listen. Reading is another way of listening. There’s so much about this. There’s not a lack of material once you’re ready, but that readiness is the first thing. And I’m like, if any woman in your life is telling you that you need support around this, listen.

AA: Yeah. Amazing. I was going to ask you to do that very thing that you did, because there are so many discreet, explicit bullet points like “this, then this, then this,” and that is really, really helpful to have that in there, instead of, like we were saying earlier, kind of nebulous theoretical ideas.

amb: I was like, I don’t want to leave it out here. I want to make it very much like in every aspect of your life, here’s where this happens and what you can do.

you have to recognize that you are a part of patriarchy, you’re part of a system. And for a lot of men, that first step is the biggest one

AA: Yep. Okay. Changing subjects a little bit. You write in the book about Israel and Palestine, and you’re very clear in the book that we need to make sure that Jewish people feel safe and are safe everywhere in the world, as well as your belief that no people is deserving of genocide and erasure. So, how can Loving Corrections help us bridge that space?

amb: I think that this past year has been really remarkable in a lot of ways in this. Because it’s very hard to do educational work when people are dying, right? And it’s like, “You need a year-long process to understand what Zionism is doing and where it comes from and all this.” And during that year, all these people are dying. So I think that this has been a really humbling year to be like, “Wait, first, let’s just stop the dying and then we can have a whole conversation.” And that’s just not how it’s played out. At the same time, I have seen more people than ever before, and I think we have more institutions, more corporations, more global entities that are all speaking very clearly about this now and just being like, “Okay, we actually see what’s going on.” I think the Loving Corrections piece, especially when it comes to Israeli folks and to Jewish people, is being able to actually hear the pain that undergirds their sense of identity. And I feel blessed because I’ve gotten to have a lot of Jewish people close to me in my life, as well as a lot of Palestinian and Lebanese people and other folks. But being in close relationship with Jewish people, I’m like, “I can see the whole path. I can see what you were told from birth about your safety and that it just was never there. And what you were told about Israel and what you were told about your place in the world and that everyone wants to hurt you.” And I also know that anti-Semitism is real. And it takes nothing away from me to acknowledge that it is a real thing that happens and that there are periods when it’s really rising, and there’s no reality in which fascism is on the rise globally that Jewish people are not going to feel terrified.

And none of that justifies what’s happening in Palestine and has been happening in Palestine. And it helps to bring it home, like to me, to live in the US is to have very direct relationship to this. We live somewhere where there were entire people here who were genocided, and by miraculous, persistent survival mechanisms, there are still Indigenous people on this land who are still stepping into leadership and still offering wisdom. I mean, that there’s no gratitude we’ll be able to ever offer that’s enough for when Indigenous people are still willing to– it would make sense if they were like, “We’re not talking to any of y’all ever again.” But instead it’s still like, “No, we built community with you.” But we can’t go back in time and undo our history, and right now we’re centuries into trying to figure out right relationship.

So for me, my solidarity with Palestine, even though I recognize that there are a lot of differences, there are some fundamental similarities which have to be taken very seriously. And you can look at the visuals, you can read the stories, and any people who have displacement in their history can look at this and understand what’s happening. So some of it is just loving people enough to slow down and have the conversation. One thing I’ve noticed this year that has been really deep is, you know, I am in a lot of relationships with anti-Zionist Jewish people, but even the Zionist Jewish people that I’ve interacted with, very few of them have been in any denial that it is an apartheid state and that it is unjust. The issue that they come up against is, “Well, we don’t know what to do.” And I’m like, there’s got to be a better option than genocide. But there also has to be a better option than occupation and apartheid. Just in the same way that the Jim Crow South and “Separate But Equal” doesn’t work here, there are so many places in the world where these experiments have been done, where apartheid in some form was able to precursor a genocide. I think of the period of enslavement for Africans who were brought here as a long genocidal period, where people were being brought here and worked to death and being killed in numbers that we’ll never be able to fully track. And then afterwards was like, apartheid will be the way that we’ll navigate moving forward. It just never works.

And all people who know that they are not less than anyone else eventually have to push back, fight back, do something. So you can’t just have sustained apartheid and you can’t have genocide. And I think that if you can get to that place, then you’re having a real conversation. And the outcomes are maybe different for each set of people who have that conversation, but you have to at least get to that place where it’s like, “Can you agree that it’s not these two paths? That whatever we’re figuring out together has to be some third path.” And there are examples. We do have living examples of places like Bosnia, like Rwanda, places where horrific, horrific acts have happened, and then people are recovering and there’s truth and reconciliation methods, there’s sanctions, there’s different things that we do to try to right the relationships. No humans have figured this out. This is a collective problem. You can never have genocide happening in one part of the world without international permission and support, usually. Part of why I keep talking about Palestine while I’m in the US is that I’m like, what’s happening there would not be possible without our support.

AA: Not at all.

amb: It would be a really different conversation, I think, if it wasn’t the case. Okay, you may not want to pay attention to it. I think this has been a big thing with Sudan and the Congo, is trying to get people to pay attention when they’re like, “I don’t understand how to follow the financial impact and make the connections.” I’m like, it’s possible to do, we are still connected to that one. And with this, you can literally follow the checks. It’s announced every time Congress sends the money, it’s for weapons. It’s all very, very clearly documented and it’s defended by every candidate running for office. No one is hiding any of what’s happening. So I think the main thing that I keep trying to do with people is just be like, can we get to this precipice where we recognize that it’s not this or that? There’s got to be some other option here. And for people who live in the US, I think the main thing we have to figure out is what is our right relationship with Indigenous people here and with biodiversity and right relationship to land here, in addition to stopping that flow of money towards death. And then I do think that we have to leave people to their own devices, also. Like, “Y’all are going to figure it out. You’re going to figure it out.” Our job is just to stop feeding the fire. But then, like all humans, we don’t know how to do this. We’ve never figured it out. Americans, we need to be so humble right now. We do not know how to do this stuff. We are in a dumpster fire of a mess of a nation, and I don’t think we can call this a functional democracy right now. So we can’t export something we don’t have. And I think what we’re seeing right now is partially what happens when we try to do that everywhere.

AA: Yeah, absolutely. I absolutely happen to agree with you on every single point you just made. And I have to say, too, we do need to be humble and realize that we don’t know what we’re doing and we haven’t been able to figure out our own problems. And, as you’ve said at other points in this conversation, I have this hope, too. And humans are actually incredibly smart and incredibly resourceful, and we should have been able to have learned from past lessons. So if we were able to take our hearts and minds and apply what we’ve learned in the past toward the solution and come up with something more creative, and learn from, like you said, learn from other places that have done something similar and recruit our best thinkers and something that’s in line with our values. I think it can be done, but it just takes the resolve, and in the meantime, the killing has to stop, like you said.

amb: Yeah. And I think recognizing that for anyone who has experienced a wrongful death, like if you’ve lost someone that you knew, “I wasn’t supposed to lose that person.” If they were killed or they died by suicide or they died by medical mishap, you just know when you’re like, “That person is not supposed to be gone and they’re gone.” If you can just imagine what it feels like to have one death like that in your life, or if you live through an epidemic. I think of people who lost tons of people during the AIDS epidemic, things like that. What it does to your soma and your system, and what it takes to repair… Each person you’re taking, you are planting so many seeds of grief and harm. So I think that right now, the humility is that we’re going to spend a lot of time healing from this. We have to stop so that we can begin any kind of repair. And I have had to really notice that for myself that I’m like, I have to stop trying to imagine the full outcome right now. It’s just like with anything. If you’re beating me, you just have to stop beating me and then we can talk about how we get right round. That’s the thing with men. That’s what’s happening with the #MeToo movement. That’s what’s happening with the Diddys and the R. Kellys and the Harvey Weinsteins. All of it. You have to stop harming us. And I see it all as very connected, like a way of saying, “I’m going to extract and take what I want, and who cares who I hurt? And if I have to take people out in order to have my way, I’ll do that.” It’s a whole way of being that is not compatible with life on Earth. So we have to let it go and grow.

AA: Yeah. Well, we always end our episodes with a call to action. And I will just say, I’m going to offer the call to action to listeners to buy the book, Loving Corrections, because you’ve provided already in this conversation so many things, actual steps that we can take to dismantle harmful systems and to build just ones in their place. So, adrienne maree brown, thank you for this conversation. Do you want to tell people where they can find your work?

amb: Yeah. Well, I always say that if you can buy the book directly from AK Press, do. They’re a really cool, small press and it matters when you buy it directly from them.

AA: Wonderful.

amb: And then I’m on Instagram, I post memes there and I try to be a positive force in that realm. And then adriennemareebrown.net is my site, and my sister and I do a podcast called How to Survive the End of the World, that I think is a really great podcast space. We have really deep, meaningful conversations with each other.

AA: Fabulous. Well, I highly recommend it and thank you so much.

amb: Thank you, sweetie. I believe in us.

It is absolutely possible in your lifetime, in a generation,

to personally relinquish an unjust ideology.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!