“Singing our own songs, telling our own stories, enjoying them for what they may become.”

Amy is joined by Channel Achenbach to discuss Daughters of Anowa by Mercy Amba Oduyoye and explore history and gender relations in Ghana.

Our Guest

Channel Achenbach

Channel Achenbach hales from San Antonio, TX and is an advocate for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” She is a seeker of freedom, justice, accountability, love, compassion, mercy, diversity and awareness. She pursues opportunities to discuss racial disparities and the achievable resolutions for unity, diversity and solidarity within the membership in and out of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Channel has been a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints for more than 30 years, leaving following her mission. Channel is married with seven kids and one grandson.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy, I’m Amy McPhie Allebest. If I were to ask you to take a pre-test on African religion, what would you guess about the historical timeline and the current religious affiliations of the population of the African continent? Make a guess in your mind and now I’ll set the scene for today’s episode.

Like human beings everywhere, for thousands upon thousands of years, the people of the African continent practiced Animism, which is a religion that focuses on nature and on deities that represented different strengths. It’s a religion that honored ancestors and imagining possibilities for an afterlife. There was almost an innumerable diversity of these religions on the whole African continent, but in the year that Western civilization retroactively labeled the year 1, Christians believe that Jesus was born in Israel, and soon after that, his family fled to Egypt to escape the King Herod’s murder of all the Hebrew baby boys. This story is told by Egyptian Christians to this day, and legend has it that Christianity first officially arrived in North Africa when St. Mark arrived in Alexandria, Egypt in the year 60 CE. So Christianity has been on the African continent for a long, long time.

Once in North Africa, Christianity spread slowly west from Alexandria and east to Ethiopia. Through North Africa, Christianity was embraced as the religion of dissent against the expanding Roman Empire. In the 4th century, the Ethiopian King Ezana made Christianity the kingdom’s official religion. In the seventh century, Islam arrived from the Arabian Peninsula and began to gain converts very rapidly. Large swaths of the continent became Muslim, and others Christian, and still other regions retained their traditional religions. In the 15th century, Christianity came to sub-Saharan Africa with the arrival of the Portuguese. And in the south of the continent, the Dutch founded the beginnings of the Dutch Reform Church in 1652. In the interior of the continent, most people continued to practice their own religions undisturbed until about the 19th century. At that time, Christian missions to Africa increased. However, where people had already converted to Islam, Christianity had little success. As of 2020, 62% of the continent’s population was Christian. Muslims followed, accounting for 31.4% of the total population, and 3.2% of the people in sub-Saharan Africa practiced traditional African religions, and 3% of the population reported that they were unaffiliated.

Okay, so that was much more Christian than I expected. 62% of the continent of Africa is Christian as of 2020. And as I learned from the book that I read for this episode, these numbers are much more complicated than they look because traditional religion and story and local culture interact with Christianity and with Islam in very unique ways, as they do all over the world.

So, the book we’ll be talking about today is called Daughters of Anowa: African Women and Patriarchy, and it’s by the revered African Christian feminist author, Mercy Amba Oduyoye. And to discuss this text, I’m thrilled to welcome to the show my friend Channel Achenbach. Welcome, Channel!

Channel Achenbach: I’m glad to be here!

AA: Okay, so Channel, can we start out by you telling us just a little bit about yourself, where you’re from, and some of the things that make you you?

CA: Yes. I am originally from San Antonio, Texas, and I’ve been in Utah since 1997. I am married and I have seven children, and I have a grandbaby that I love spending time with. I do spend a lot of time just absorbing information about women, about marginalized groups, and I’m telling you, my mind is absolutely blown, because you hear misogyny and you hear patriarchy and you think, “okay, it’s just when men are mean to women.” It is so much more than that. It is so deep-rooted from centuries ago, especially throughout Christianity, which I did not realize. So that’s a new thing for me. I mean, race I can tell you about that all day long because it’s something I experience every single day of my life. Patriarchy is a little bit different. It’s different because it affects so many women differently. So, race I understand as a Black woman, but now understanding patriarchy and misogyny, that’s a different thing.

AA: Thanks, Channel. Okay, so one question I wanna ask too before we dive in, is that when we were talking about doing an episode together this season, I set out a ton of books and said you could pick a different book that you want or you could pick one of these, and you were the one who chose Daughters of Anowa. Can you tell us what drew you to this book?

CA: Yes. One of the things that drew me to the book is that it referenced African women and patriarchy. And I was fascinated with reading what it was like for women globally to experience patriarchy, especially women from a region my family descended from, which I think is important because then it, I guess, foreshadows what’s happening now.

AA: Yeah, that is so interesting. I’m curious too, Channel, have you done DNA tests or are there family stories so that you know which region of Africa your ancestors came from?

CA: Yes, I did 23andMe I believe, and I learned a lot about our family history. That’s what drew me to the book because I knew where I was from, and Ghana is part of it. And so when I saw the book, I definitely wanted to know more.

AA: Okay, well let’s dive into the book and to introduce, as usual, we’ll talk about the author. And today we have a little bit longer of an author intro because when we went to her website, there were some amazing stories about her. So we’re gonna get to know her a little bit before we start talking about her book. So the author’s name is Mercy Amba Oduyoye, and she was born on her grandfather’s cacao farm in Ghana in 1934. She’s the oldest of nine children. Oduyoye attended a prestigious Christian boarding school in Accra, where she obtained an excellent education. As a young adult woman in 1952, Oduyoye grappled with limited career choices. Women were either trained to be teachers, nurses, or secretaries. And here in the bio, I thought, I think it was that way everywhere. It was definitely that way in the United States too at the time, in 1950– It’s still that way! Women are totally funneled into those careers: teachers, nurses, and secretaries. Still, I mean, it’s improving but…or they married and worked various jobs to support their families. So Oduyoye decided to attend the teacher’s training college at Kumasi College of Technology in Kumasi, Ghana. After completing her post-secondary certificate of education, she taught at an all-girls middle school, and during this time, she also cared for three of her siblings while her father, accompanied by her mother, pursued a Bachelor of Divinity degree in London. So they left her with her younger siblings to take care of.

When her parents returned, she entered the University College of Ghana, and in 1961 she received the Intermediate Bachelor of Divinity from the theology department of the University of London. And in 1963, she became the first woman to graduate with the Bachelor of Arts Honors Degree in the study of religion from the University of Ghana. Amazing accomplishment. And in 1964, she graduated from Cambridge in the UK with a degree in Theology. She went on to receive a Master of Arts, also from Cambridge. She returned to Ghana in 1965, not to teach at the university as she had expected, but to teach at a girls’ high school for two years. And through her mentoring and exceptional teaching at this school, she inspired numerous girls to pursue Christian theological studies and world religion. In 1968, Oduyoye married a Nigerian-born man, who was a renowned linguist, writer, publisher, and Yale graduate. Oduyoye had grown up in the Methodist Church and in an Akan matrilineal context – and we’ll talk about the Akan for most of the episode – this was a different ethnic group from her husband. Her husband was a member of the Anglican tradition, and he was a Yoruba of patrilineal descent. So these differences would play an important role in shaping her work on women’s rights, and it comes up in the book a lot. She also had experiences at work that developed her gender consciousness. She taught in many different capacities at many different schools, and when she joined the religion department at one university, she had two experiences that made a big impact. And I do wanna share them because I thought they were so interesting. She said that first, she was the only woman on the faculty of the department of religion, and she was asked during her first faculty meeting to make tea for the faculty. And she was really stunned by this and not happy. She got up from her seat, she picked up the phone on the professor’s table and called the administrative secretary of the department, who happened to be a man. The administrative secretary is normally in charge of refreshments, and in front of all of these men in the meeting, she said, “Hi, the professor says the staff is ready for their tea.” And so don’t you love that story? I love it so much! Instead of going and getting the tea but fuming about it, she didn’t do it. She called and said, nope, that’s not my job. She soon realized that the men thought it was her responsibility to make the tea, but she said that by calling the person in charge of refreshments, she asserts “I gave him his job back.” I love it. I love her.

Another incident at this same university involved a discrepancy between the allowances that were given to male and female faculty and staff. For example, the man with whom she was appointed at the time appeared to be receiving a vacation allowance that was double the amount of hers. She asked why that was, and she was told that the man was married. “So am I,” she responded. “Well, he has to pay for his wife,” they argued. She came back with, “Who told you that I don’t have to pay for my husband?” And with that, she joined the Women’s Staff Fight Association and she began fighting for equal rights and pay equity for the women. From these and other experiences, she learned quickly that men were afforded certain privileges and preferences. And she responded, “I don’t think I should live under patriarchal male dominance.” So, I mean, what an amazing woman. And she has more accolades than we could even list here, but she was a research associate at Harvard Divinity School, she was a visiting professor of World Christianity at the Union Theological Seminary during the 1980s. We’ll end with one more story, that when she was offered a really, really prestigious international position, during the interview a colleague and a friend on the panel that was deciding if she was gonna get this job said, “I don’t think this is a good image for African women. An African woman who’s gonna leave her family to come and do this kind of work (the job was in Geneva), I don’t think it speaks well and we don’t know what Dupe thinks,” which referred to her husband. So in support of his wife and in protest of this policy, Oduyoye’s husband physically took his letter of support to the Methodist church office in Lagos and demanded a note saying they had received the letter. He agreed with his wife’s decision and supported her moving to Geneva and taking the job. So good for him, too.

She’s still living, she is 88 years old and she’s the director of the Institute of African Women in Religion and Culture at Trinity Theological Seminary in Ghana. So really quite a hero, and we’re so excited to feature her work today. We’re gonna take turns sharing parts of the book that we thought were really illuminating about specifically the Akan culture in Ghana and the Ivory Coast. So Channel, why don’t you take it away and share some of the parts that you thought were the most important.

CA: Well, first I wanted to address the title of the book, Daughters of Anowa. So, this is actually a play that Oduyoye references. And in the play, Anowa rejects the men that her parents want her to marry. She marries a man of her choice because of love. But the marriage ends tragically, and also in the death of her and her husband, his name’s Kofi. Now, the marriage is frowned upon and discouraged because the suitor isn’t chosen by either parent. And we’ll learn later how significant that is, especially when it comes to the father choosing as opposed to the mother, and correlation to the parents both choosing together. But she starts having trouble with her husband, Kofi, because she’s independent and because she thinks for herself and she’s not following a line of submission for him. She questions him because he’s a slave trader, and she’s against slavery. He doesn’t like it very much, and he’s annoyed and bothered by her asking him about it. He finally tells her to leave, but they start arguing and then she confronts him about not being able to have children because she really wants children. And the interesting thing is, in her wanting children, she even suggests that he go outside the marriage to, you know, have children and he’s kind of like, mm, no. What she realizes is that he can’t have children, and he doesn’t like that because he feels emasculated. And so they’re fighting and he tells her, “just go away!” And she’s like, “no, I don’t wanna go away.” So then feeling emasculated, he goes and he takes his life. And her being so distraught and pained, she takes her life.

And the reason why this is very important, especially in the Akan, is that they say that if you don’t listen to your parents and who they’ve chosen for you to marry, especially your father, then your marriage is doomed no matter what you do, or no matter how happy you think you are. So this is very important because think about it, she dies by her own hands and he dies of his own hands. And if she would’ve just listened to her parents, she would’ve never married him and she’d be happy right now. And so that is huge throughout the vibe of this book.

AA: I’m really glad that you pointed that out. So that the daughters of Anowa, she’s kind of saying, are like the women at least of Ghana where she’s from, right? Kind of like this curse of: just remember, if you depart from what your dad tells you to do – which is literally what patriarchy is: the rule of the father, the rule of the man – you’ll have bad consequences. And that that’s hanging over them all the time. So the next thing we wanted to talk about actually, is to give some more context about the Akan people. I had never even heard of the Akan people, had you, Channel?

CA: Well, not in this context, but I know a man who is from that tribe and he talks to me a lot about what they still believe.

AA: Oh, that’s so cool! Wow, I didn’t realize that. Okay, so let’s take turns talking about things that we learned in the book about the Akan. So the Akan, as I mentioned before, is an ethnicity. It’s technically a meta-ethnicity, which just means more broad than ethnicity and nations. So it incorporates lots of different ethnicities and nations. But the Akan live primarily in the countries of present day Ghana and the Ivory Coast in West Africa. The Akan subgroups all have cultural attributes in common, and most notably, one of those is the tracing of matrilineal descent. And we’ve talked about that on many episodes of the podcast in the past. But the Akan has a really interesting way of practicing matrilinearity. There’s a quote in the book that says, “the priority of matrilineal groups is the birth of female infants. For without them, no blood can be transmitted and no ancestors can return to life, dooming the clan to extinction. Male children are accepted and welcomed because there are trees to fell and wars to fight.” But they actually truly do prefer girl babies, and I think that’s the first time I’ve ever heard of that. I mean, everywhere on earth has historically tended to prefer male children, even killing girls babies in lots of different cultures. This is the only one where they really, not only would they welcome both, but they do prefer girls. And I also thought it was an interesting feature of the Akan that they really do believe that ancestors are being reincarnated, coming back to life through the children. I thought that was so interesting.

if you don’t listen to your parents and who they’ve chosen for you to marry, especially your father, then your marriage is doomed no matter what you do

CA: Yes, my friend that I talked to is Akan and he talks about that. And when he was saying that, I was like, “What?” He’s like, “No, we are reincarnated.” And he brought up like on the skin, he’s like, “I have a mark that my grandfather had, and my aunt has a mark that her mother had and they’re reincarnated.” And I was like, “What?!” And so I just thought it was amazing to listen to him describe what that means.

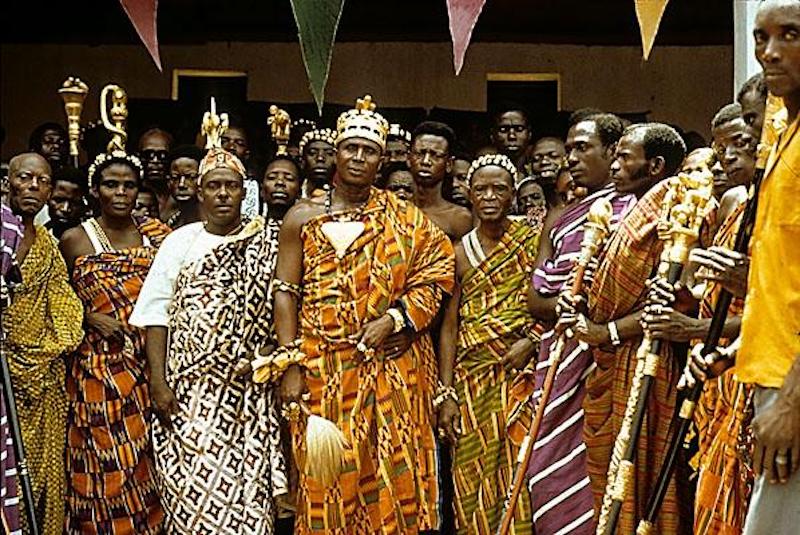

AA: Yeah, it’s really beautiful. I don’t know that I necessarily would say, “oh good, you prefer girls.” I would love to have all babies be equally wanted, right? But it was interesting to encounter a culture that truly does prefer girls. One other fun fact that I thought was so lovely and interesting is that it was the Akan culture that developed the kente cloth, this beautiful textile that was developed by the subgroup of Akan called the Ashanti. And many listeners may have seen these beautiful cloths at weddings or graduations, people of African descent often wear them at celebrations. So I thought that was really neat that that came from the Akan.

CA: Tragically, the culture was deeply impacted by the transatlantic slave trade. Roughly 10% of the ships containing enslaved people that embarked from the coast of West Africa contained the Akan people. And in the Americas the Akan captives were known for their various slave revolts and plantation resistant tactics, which I think is great.

AA: Another feature of the Akan culture is that motherhood is of paramount importance for women. A quote from the book said, “Women are not valued in themselves, but only as valuable objects or means to an end.” Again, this is so common to so many cultures worldwide throughout time. It’s so interesting too, because I remember in my International Women’s Health and Human Rights class, we studied different African communities and how it’s really hard for groups that are going in to help women advance, it’s hard to convince them to curtail their childbearing. Because there’s still so much a culture of thinking of children as your pride and joy really, and also your wealth. But especially for a woman, who you are as a woman is very connected to how many kids you have, and so that’s a real cultural difference. And so it also makes it hard in a lot of African countries and communities and cultures to use birth control. Like, why would we want to limit the number of children we have? Let alone reproductive rights or abortion. And also, Oduyoye talks about how this is why people accept polygyny so readily. And you mentioned this, Channel just now, in the play of the Daughters of Anowa, she says like, “We need to have kids. It’s okay, go find another wife if you need to. Our family needs kids.” It adds to the men’s honor as well to have as many children as they can have. And that’s a complicated issue, right? For a woman to want children but then also realize that that will definitely impact the amount that she’s able to thrive in her own life. I mean, a lot of women listening can relate to that.

Anyway, another feature of the Akan is that they are not patrilocal or matrilocal. They’re flexible, when a heterosexual couple gets married, it’s flexible whether they go to live with her family or his. It’s not designated inflexibly.

CA: So another interesting feature that was mentioned in the book is that men and women live separately. Around a hundred yards away from each other, there is a head of a woman’s quarters, like a matriarch, but she’s presided over by men who are the head of the family. Little kids could run around freely, back and forth until they get to the age where the adults start to shame boys for hanging around girls. And especially the kitchen; strong taboo around the kitchen for men. That is the woman’s domain, do not step there. That is the only place that they’re able to do their thing and be praised for it. And girls start to get told, “you’ll never learn to cook if you don’t go back to the woman’s quarters.” No strict distinction between nuclear families; you’re an adult, parent, aunt, uncle, which means you love and can discipline any child. Or you are a child, not so exclusively any one couple’s child. The author says she’s still not sure which of her cousins are the kids of which aunts and uncles. So it’s something personal I did want to say, about when they’re saying that not one person is over the children. I noticed that in my own community growing up, everybody was disciplined and chastised by everybody. It didn’t matter. Somebody’s mother from down the street could spank you or talk to you, and that’s how it was done. So that’s still being passed on. But another thing that I saw in this book is that even among the matrilineal Akan, the marriage relationship is androcentric.

So in the Akan household, the husband, it’s interesting that he’s supposed to have control over his wife, try to be nice to her, but still she’s like property and he’s her boss and he gets to have her do everything. She can’t make her own decisions without his permission first. He wants her to be smart, and great, and wonderful, but not challenge him with those attributes. He controls what she does and how she does it. And with this, one thing I wanted to say which was kind of mentioned in an earlier comment: when a woman is expected to have children, bear children, that’s a huge thing. There’s a lot of rivalry with the women. So if there’s polygyny and one woman can’t have a child, she’s ridiculed by the other women, and if she loses a child, then something’s wrong with her. Not only from birth is she tortured with an image of what a woman is (that’s negative), she has other women – which in the Akan is her only support – she’s now catching pain and suffering from other women. So I just think that was important.

AA: Another really interesting discrepancy between the genders was how a man and a woman in a marriage would mourn if one of them died first. So Oduyoye says, “When a man dies, his wife mourns for him for three months. She must not plait her hair, and if already plaited, she must loose it. She must not take a bath for three months. She must not change the clothes which she was wearing at the time of her husband’s death. She must sleep on rag mats. She must keep indoors for the three months, and if she cannot help going out, it must be in the evening, but such cases are very rare. In some cases, she may not be allowed to remarry.” And as I was reading that, I thought, Wow, that’s really intense, but it would be fine if men do the same thing for their wives, then I guess it’s reciprocal, but that’s not the case. She said the traditions for widowers are not as demanding or as demeaning.

CA: So in the religion of the Akan, there are women creators and women protagonists. They’re not just on the sidelines. However, Oduyoye says myths are structured to make sure that all female rebels are duly contained. These myths are society’s way of pleading with the women to put community welfare above their personal desires. Through these myths, the society demonstrates the futility of a woman’s efforts to change her destiny. The women who seek veneration as goddesses are in the end those who allow themselves to be sacrificed. Well, for me, African myths are constructions of a bygone age that are used to validate and reinforce societal relations. For this reason, each time I hear “in our culture,” or “the elders say,” I cannot help asking, “for whose benefit?”

AA: That is such a great question. For whose benefit? I feel like that’s a great question that can be applied to all kinds of policies or power dynamics that don’t feel right. For whose benefit is this? Okay, so we’ve been talking a lot about the Akan people and their indigenous culture and Oduyoye’s critique of the patriarchal structures within the Akan culture. But I want to shift gears for a minute, because Oduyoye writes a lot about Christianity, too. She is a practicing Christian, but she’s not afraid to criticize injustice wherever she sees it, and she doesn’t spare Christianity either. And she says this:

“There is a myth in Christian circles that the Church brought liberation to the African woman. Indeed, this is a myth. What actual difference has Christianity made for women other than its attempt to foist the image of a European middle-class housewife on an Africa that had no middle class? Africa finds little sustenance in the continuing importation of uncritical forms of Christianity with answers that were neatly packaged in another part of the world. These churches, which most often take the form of patriarchal hierarchies, accept the services of women but do not listen to their voices, seek their leadership, or welcome their initiatives. It is painful to observe African women whose female ancestors were dynamically involved in every aspect of human life define themselves now in terms of irrelevance and impotence. This distorts the essence of African womanhood.”

I think it’s really interesting here how she says that these “African women whose female ancestors were dynamically involved in every aspect of human life,” these are the Akan people, right? This is the Akan culture that she was just criticizing, and she isn’t afraid to call out the difficult aspects of it, but seems to imply that it was better under that system than the patriarchal Christian system that really marginalized women. And another thing in this quote that I thought was interesting is she says that “Africa finds little sustenance in the continuing importation of uncritical forms of Christianity.” And that word uncritical I think is really important because again, she’s not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. She’s not saying that Christianity is all bad, but she’s saying that we need to use our critical thinking and we need to be able to criticize the things that are not right within this religion that she still loves and practices. Okay, one more quote from this section that I wanted to share. She says:

“In assigning roles based on gender, the theory of complementarity plays a negative role for women in domestic organizations and in the Church. In practice, complementarity allows the man to choose what he wants to be and to do, and then demands that the woman fill in the blanks. It is the woman invariably who complements the man.” Woo! Those are some concise and powerful critiques. So Oduyoye points out that Christian stories and ideas made and continue to make a huge impact on Akan culture. So there’s this interweaving of Christianity with Akan culture, and she’s trying to parse them out, and again, identify the patriarchal aspects of both. But now we’ll go back to indigenous Akan narratives and we’ll talk about the folktales and proverbs. So can you talk about those, Channel?

each time I hear “in our culture,” or “the elders say,” I cannot help asking, “for whose benefit?”

CA: I wanna talk to you all about folktales in the Akan culture, which is huge. It’s what they use to start forming images about women to the young. It’s their holy writ. So when the Akan are young, the anansesem, which is spider tales, is what’s popular and taught to the young until they’re older, more mature. Then after that, the more serious teachings like, I’m gonna foreshadow here, the proverbs. I mean, this is what they use to talk about women and paint the image of what a woman is so you’ll know how to respond to her. The folktales guide the community and they’re what teaches the whole community, not just the young kids, about what is expected of the women and their roles. And the folktales also establish a huge image of how you’re supposed to interact with them, men and women, boys and girls. And so examples of folktales, one is that gender is everything, especially for a male; self-affirmation in a male is admired and labeled masculinity. However, that same characteristic in a woman is considered selfish and egotistical. Children are taught to please and obey the father. Young boys, brothers of some of these young girls, start young dominating, belittling, and oppressing their sisters. This is preparation for misogyny and patriarchy. This next part here blows my mind. So, picture what a witch is. “Many African folktales describe old women as demons. Often they have the power of metamorphosis to alternate between human and non-human forms.” And there’s a story about Emery. There’s a king that is great at his work, physical labor, and he beats palm nuts for his wife, Emery. He does this because women are thought of as being demanding gold diggers and overbearing, so that’s why he’s doing it for her. This harsh image will be explained later as expounded in the proverbs. But his wife Emery is no exception to this harsh image. She is said to be a witch and won’t assist him while he’s working. So a god told the king what he must do with his favorite wife. The king traps her, destroys her, and then he prospers. So he has to take this wonderful woman, who’s actually great, but she’s considered a witch. And because she won’t help him, there’s so much disdain towards her, and so he traps her and hurts her, and that’s just so weird to me.

Another aspect is women in marriage. “A favorite theme in many folktales is that girls should not be strong-willed in matters of the choice of her spouse or marriage.” Sometimes a folktale gives an additional caution against leaving home to live with a husband in a place where one has no blood relations. There’s a folktale about a young girl that refuses suitors chosen for her by her parents. She runs free in the forest in search of conquest and adventures of her own volition, and stumbles upon a handsome man, falls in love, and runs home to tell her parents. She’s married and goes off to live with her husband. She realizes that he’s not as he seemed. He’s revealed to be a python that swallows the whole bridal party, but just before he’s about to swallow her… her brother shoots and kills it. She’s learned her lesson.” So this part where it says that the boy came in and he shoots and kills a python, it’s so interesting to me that her brother comes in and saves the day as if she can’t make her own decisions for herself. And then the theme of people thinking, “well, obviously the boy’s smarter and more capable than she is.” That just rubbed me weird.

AA: Mhmm. And I think that’s why we both notice with these proverbs, these are wisdom tales, right? It’s like, take note. It’s like the moral of the story is: girl, don’t doubt your parents, and then if you do get yourself into a mess, don’t worry, your little brother will save you from yourself.

CA: You can’t protect yourself! The men are gonna come in and save you because you made bad choices. And a male will have to come run and save from herself, cleaning up the mess. Ugh, that’s weird. And additionally, the message is that a good compliant girl will get a good husband. So, as we learn throughout this book, parents are considered the best judges for girls in choosing husbands. More so the father than the mother. It said that the parents cannot make a mistake; it’s taught that even with little effort or lack of concern, that even if the father gets it wrong in the beginning, it’ll work out for the best in the end.

So here’s a folktale: A father was trying to find a good husband for his daughter, but was too picky, and he refused many handsome and wealthy men. Feeling like he was running out of time, he confided in his best friend that he was gonna marry his daughter to the first man he saw. The friend disguised himself as a wolf and was the first person the father saw because he went early. The man then changed from wolf back to human. The father remembered the oath and kept it. The friend married his daughter. It’s still believed, however, that the father is incapable of choosing a wrong mate for his daughter. It’s believed that girls make poor choices with bad outcomes if they choose for themselves. So it seems to me that even in our own culture and so many others throughout the world, so much confirmation bias exists among the African people to control the women. And then the folktales in this sense are dangerous and problematic, because if something goes wrong then it’s a direct result of her choice. If something seems wrong with the choice from her father, then it has to be her perception that needs to be questioned, not the father’s.

So, earlier I mentioned a foreshadowing of the proverbs. Proverbs is where my skin just gets goosebumps because these are very… they’re significant and they’re strong. I mean, they’re unquestionably one of the most important parts of Akan culture, creating the image of a woman and how she’s molded into that imagery. Proverbs reinforce these teachings. “The weight and effectiveness of proverbial language among Africans is attested by their continual daily use of proverbs today, and also by their current interest in collecting and documenting proverbs. It is also worth noting that new proverbs are being created all the time, while others are made obsolete by the changing times.” When it comes to proverbs being created and others becoming obsolete, keep in mind that the men can choose to use them or not. They’ll use them to their benefit. So if there is such a thing as a positive proverb, then the men probably won’t use it because it’s showing the woman in a good light. When it comes to the making of a man, one of them that stood out to me is when a man is in trouble a woman takes it as a joke. In the proverb, this man is suffering from his cruel wife that laughs at him. I just think it paints an awful image of women, but worse it paints motherhood– it’s so important in African culture that the mother influences her child, she even has her child laughing at him. The child is supposed to revere the father so much, but the wicked witch mother confused him. She beguiled him. And so now he’s making fun of his father. And this happens everywhere. Not all African men want misogyny, insufferable patriarchy, but are afraid of the shame and loss of support from the community if they don’t fall in line with what’s viewed as being a man and exhibiting masculinity. This is passed onto the children. The boys start with the treatment of their sisters. The girls receive it from their fathers, uncles, mothers, then their husbands. If the boys don’t learn to dominate when they’re young, then they will struggle to find wives.

So then you go to the making of a woman. One of the proverbs says all women are the same. Another proverb says that what you would not have repeated in the streets, do not tell your wife in the bedchambers. And then the third one I chose is: women love where wealth is. From these three proverbs is the image that all women are the same, which is: untrustworthy, wandering, gold diggers. And that just kind of sat wrong with me. And there’s a Yoruba word, an adverb, which is ‘gbayi’, which means vociferously and loquacious, which is loud…

AA: Talking too much.

When it comes to proverbs being created and others becoming obsolete, keep in mind that the men can choose to use them or not. They’ll use them to their benefit.

CA: Yeah, just won’t be quiet. Just keep talking. She just can’t be quiet. In Yoruba, they say that women are always talking very loudly, and the woman is always brawling. She’s always ready for a fight. Another thing is, as a mother this is very, very telling for me. It says, ‘the tortoise has no breast yet she feeds her young’. The proverbs are favorable when it comes to her only as a mother. I mean, a tortoise doesn’t have breasts yet she feeds her young, meaning she’s gonna find a way. You know, she’s gonna make sure that they’re okay. And if she can’t have children, she’s not good for anybody.

AA: Yeah, Channel, you and I have been talking as we’ve been preparing this episode about this very thing, right? About, you know, this tortoise which is an animal that doesn’t even have breasts, like you just said, but they’ll find a way. I mean, it kind of makes me ache to think that you’ll give what you don’t even have, somehow, as a mother. Do you wanna talk about that a little bit?

CA: Yeah. I think this is important to know, that even now I had to set boundaries with my spouse and my children to be able to have time to devote to this book that just had so much of my attention. I’m viewed as a mother, a therapist, a cook, a maid, a wife, anything but merely a woman. I feel like Cinderella that must complete her chores before she can attend the ball, yet beyond exhausted to do so when my task is complete. And I don’t think anybody understands this, I don’t wanna make this about me, but I think this is important to identify patriarchy. It wasn’t this Mother’s Day, but it was a Mother’s Day before. I had a heart attack on Mother’s Day, and it was very scary. It happened in front of my daughter. But then a few days later, I was up and nobody would leave me alone. I didn’t rest. And there I was again, just making sure everybody was okay. And that’s what you do. It’s like you’re just expected to just get up and go. I’m extremely anemic, I have all these things that happen, but I’m still expected to keep going. When my husband or my children, I love them but when they’re sick they cannot function. It’s like you run to them, you serve them, you’re there. But when you’re sick, it’s like, No, mom’s good. Mom’s got it, she’s strong. And I can relate to that because if you read through this book, in Akan culture she is supposed to be Superwoman. Even if she gets sick, she’s supposed to just buck up and still take care of everybody because that is who she is. She’s not seen as a person, she’s seen as a thing to take care of everybody, almost like a robot.

Now, a woman in marriage: a stubborn wife needs beatings to correct her. The husband is the victim always, and women are insufferable counterparts. Assume that the problem stems from the awful, treacherous nature of women. These proverbs paint women in a really bad nature. This is what Oduyoye says: “To better understand what is happening to African women, we should pay attention to the economic factors that affect their lives, but also be aware of cultural undercurrents that determine their status.” So I’ve talked to you about some folktales and proverbs that are depressing and sad, and just really had me thinking for two days… I really had a hard time with the image of women being portrayed. But here’s a favorable folktale. It’s a poem and I just think it’s amazing: “May we have joy as we learn to define ourselves, our world, our home, our journey. May we do so, telling our own stories and singing our own songs, enjoying them as they are for what they may become. Weaving the new patterns we want to wear, we continue to tell our tales of the genesis of our participation. We gather the whole household and begin a new tale.” Now this for me was great because there’s hope. I love the part where it says, “May we have joy.” It doesn’t have to be sad. “Singing our own songs, telling our own stories, enjoying them for what they may become.” My heart is broken for the image that’s painted of women because I love women so much, but I think in her poem, this joy – we can do it, we can tell our own stories and we can sing our own songs. It’s just… There’s hope. Let’s do this. We can do this.

AA: That’s beautiful, Channel, thank you so much. I wonder if you could share some closing thoughts.

CA: I told you I was gonna be emotional. Yeah, some of the closing thoughts I have is that I see so much of what’s happened in the communities in Africa and to African women. But in my own community growing up, I mean, I witnessed so much patriarchy, and misogyny, and violence towards women, including young girls. Violence and words that were physically harming and just devastating events to see throughout the community. Women were to keep the homes clean, accept and not question polygyny, endure physical and verbal abuse. It was normal being around cousins, family, people… Nobody was shocked to see a woman pushed down, or hit or slapped or hair pulled. That was normal and we weren’t supposed to question. And also in this book, I forgot to mention that I think it’s really important: the woman is looked down upon if she is beaten in public (which is not her fault) but also if she ever tries to complain. If she complains, she’s not seen as a good woman. Women and girls were constantly used as objects. That was horrible. I saw that a lot, where a woman, a girl even, was just taken by her cousins, by her uncles, by her uncles’ friends, by her grandfathers– and these were ministers and people that are supposed to know better! And you weren’t supposed to question, and everybody knew about it. And throughout the community you’re quiet, you accept it, you take it and you be quiet. Like in the Akan, if she complains about it then she’s not a good woman, so don’t complain. And if it happens to her in public, she is shunned. And I saw that growing up too. If somebody got hit, you just looked at them like something was wrong with them instead of something was wrong with the person doing the hitting. And these young men, as they start having urges about women, to just take them and pass them around, and them not being able to fight back because if you did, you’re in trouble… is just hard. I really have so much love for Oduyoye, she brought so much to my attention that I didn’t know. And I just feel so much empathy for women, and I mean, from being little girls they come out of the womb and they’re already told how horrible they are and what they’re supposed to do. But I appreciate you listening to me tell what I thought about some of the passages and some of the things that I read.

AA: Thank you so much for sharing that with us, Channel. I am reminded as you talk about this of a piece that was shared last season by Robert Lashley. He’s Black and he came from an abusive family, and he brought up in his piece the concept of respectability politics, where marginalized communities sometimes feel like they have to present an image of perfection to the world so that it won’t confirm the stereotypes and prejudice that the outside world has about them. And so sometimes in communities of color, abuse isn’t reported because of the racism of outsiders who would use those struggles against them and say, oh yeah, this community is X, Y, and Z. And so it adds a layer of difficulty in talking about it, and I feel really honored that you would share those experiences honestly with us. And I just want to remind listeners that abuse happens in every single country, in every single community in the world, in every single social demographic. And I also want to say that I feel like this is what Mercy Amba Oduyoye was doing with this book. We shared a lot of her criticism, and the point of the book is to critique patriarchy in both the indigenous and the Christian parts of her culture. But she’s also very proud to be Akan, and she’s still devoutly Christian. And I really admire that about her. I think that some people see things in terms of all good or all bad. But in my opinion, that’s immature thinking. Oduyoye is too sophisticated and evolved for that. She sees the good and the bad in those proverbs and folktales and social norms, and she sees the good and the bad in Christianity. And she calls out what’s bad and she embraces what’s good. And I think that’s what I heard you doing in our episode today too, Channel. And I’m so grateful that you read this book with me, I’m so grateful that you joined me for this conversation. Thank you so much.

CA: Thank you. I am so glad you gave me an opportunity to read this book and learn more about patriarchy, which I am learning so much about. I appreciate what work you’re doing and the information I’m receiving, so now I’m sharing that with other people. You’re appreciated as well.

May we have joy as we learn to define ourselves,

our world, our home, our journey

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!