“my mother’s voice was a rocketship”

In this episode it was my honor to be joined by poet Robert Lashley, who shares a stunning story about the books of Toni Morrison, American literature, and a son’s unyielding love for his mother.

Our Guest

Robert Lashley

Robert Lashley is a 2016 Jack Straw Fellow, Artist Trust Fellow, and nominee for a Stranger Genius Award. Robert Lashley has had work published in The Seattle Review of Books, NAILED, Poetry Northwest, McSweeney’s, and The Cascadia Review. His poetry was also featured in such anthologies as Many Trails to The Summitt, Foot Bridge Above The Falls, Get Lit, Make It True, and It Was Written. His previous books include THE HOMEBOY SONGS (Small Doggies Press, 2014), and UP SOUTH (Small Doggies Press, 2017).

His latest book THE GREEN RIVER VALLEY, was released from Blue Cactus Press on June 17th, 2021.

The Essay

If, as Oscar Wilde said, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars,” my mother’s voice was a rocketship. Graduating from The University of Washington in 1973 with a major in African American studies and a minor in Latin American studies, Glennis Wilson was one of the finest literary minds I have ever heard or will hear. As an intellectual, she was a great misanthrope, and like all great misanthropes, a broken-hearted idealist underneath. My mother carried the scars of being excommunicated from progressive antiwar, black power, civil rights, and socialist movements for the sin of her occasional skepticism. Yet it was in literature, in the writers and like-minded people who represented democracy better than founders and most fortunate beneficiaries, where she found her true exemplars of the human condition.

I remember her sentences: rapid, clear, crisp, and so elegant that I wanted to record them. She modulated her kinetic tone to create particular moods. She could be rueful when telling how people mistook Hemingway’s suicide notes for boasts and instructive when talking about the best and worst of William Faulkner. She could be erudite when talking about Margaret Atwood and eager to listen to others and learn about Alice Walker and Gloria Naylor. She could be gentle when talking about the women in the novels of Ernest Gaines and John Edgar Wideman and respond with fury when the subject turned to Saul Bellow. In every aspect of my formative years, her voice dominated my inner life and gave me the idea of the written word having meaning.

In the mid 70’s she shelved her aspirations as a literary critic to support my father’s landscaping business, and for a time, she was highly rewarded for that financially. By the time I was schooling age, my father’s crack habit had left her destitute. In between Section 8 facilities with my brother and me, my mother read and talked about literature as solace in her life and a way to pass on what she knew. In walks to and from food banks, in her new-old Chrysler, in the break room where she sold jewelry, in my aunties’ house, and at my grandmother’s, my mother gave me American literature at a very young age.

I was too young to know all she was talking about, but was reading at college level in the 1st grade. What I knew more than anything was that no writer meant more to my mother than Toni Morrison. My mother taught me that she and Atwood were America and Canada’s answer to the boom writers (Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez), phenomenally schooled novelists influenced by Faulkner, Franz Kafka, and James Joyce whose inventiveness was as distinct as their brilliant prose styles. She also taught me that Morrison was the most evident heir to the tradition of Zora Neale Hurston in bringing more of the vernacular, myth, ritual, ceremony, and interrelationship dynamics of African American life to the page.

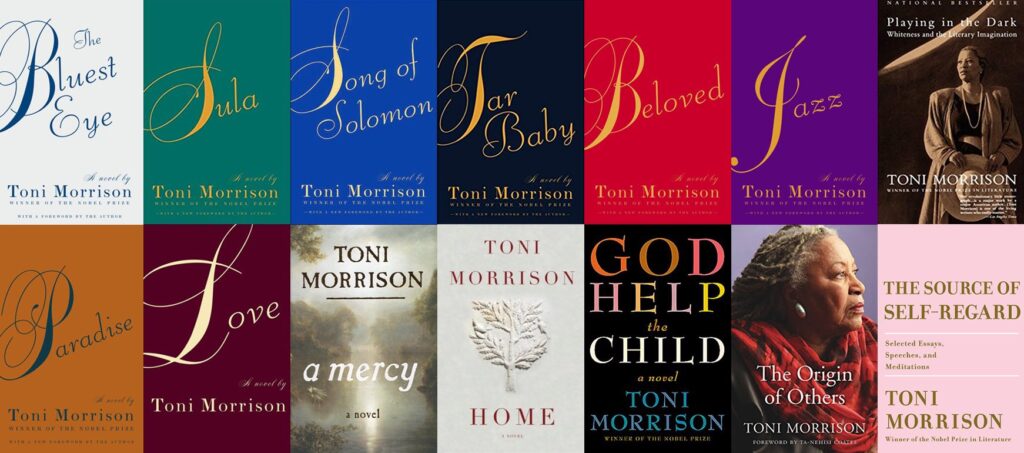

Her three greatest novels: 1974’s Sula, 1977’s Song of Solomon, and 1984’s Beloved made her the singular figure in American literature until she died. Also important to my mother, grandmother, and aunts were that she did it while being one of them. She was a single mother raising two boys. She worked her ass off micromanaging her time. Writing brilliant books and being a dutiful editor, she showed a work ethic that they could relate to. To my mother, grandmother, and aunts, Toni Morrison wasn’t their hero. Toni Morrison was their secular north star.

In walks to and from food banks, in her new-old Chrysler, in the break room where she sold jewelry, in my aunties’ house, and at my grandmother’s, my mother gave me American literature…

My discussions with my mother about Morrison are timestamps now. Being 14, newly in the suburbs, and struggling to understand Jazz’s prose and narrative tricks (she wrote Jazz in experimental length and verbal licks, instead of her trademark lyrics sentences). Starting as a freelance writer at 25 after years of being dysfunctional, yet getting cussed out by her when I parroted the proper conservative cliff notes about the novels Paradise and Love, dedicating myself to be a serious creative writer and absorbing everything I could from my mother while we were discussing Morrison’s body of work and the later novels.

It took until I was 33 for my mother and I to even breach the subject of The Bluest Eye. She first refused to talk to me about it, saying (not without cause) that I was too young to deal with the intense subject matter.

By the time I was 15, however, the reasonings had changed. My uncles had openly expressed their suspicions about my father, and I had turned into an intensely troubled, deeply suicidal teenager, and to even mention that book was something that would make her cry. It was only when I was 33 and too close to the crossroads via a drug and alcohol overdose, where she made the trip to have the most intense conversation we would have in our lives.

I had come a significant way from being a frail ghetto nerd and an insanely troubled teenager. With the knowledge I learned from hanging around my Uncle Moe (the first poet in my family), I published my first chapbook in 2008 and developed a name in poetry scenes. With hermit tendencies to this day, I was overwhelmed by the local response I got. I didn’t know that I was supposed to write slam poems centered on talking to white people. I didn’t know I was expected to write ashy nationalist scrolls telling Black women what to do or pleasant gossamer ballads that watered-down who I was and made everything about my culture tailored for white people’s comfort. I wanted to write what I knew, what I felt, and what I understood of my history; and suddenly, I was in these places where I was this lightning rod that was pissing so many people in poetry scenes off.

To my mother, grandmother, and aunts, Toni Morrison wasn’t their hero. Toni Morrison was their secular north star.

I had also developed enough of a name to remind Black Tacoma of my father. Right when he sexually abused me, a month before I turned nine, I knew that I couldn’t tell anyone about it because of how loved Bob Lashley was by Black men. In segments of high and low, the myth of my father as the wronged man had tremendous power. He owned Lashley Landscaping, a Black business in the pacific northwest that, in its heyday, employed a lot of Black people. He won a civil rights case against a marine base that had discriminated against him and ended up a broken addict of a man because of it. Bob Lashley was a fallen Black king for so many brothers, and they did everything they could to put him back on the throne until he showed them that he didn’t want to be anything but a monster to anyone.

What broke me, and what sent me into hell, is when it became public knowledge. Five years later, in 1992, a person found out what he was doing to me and let people know, and the response was a brutal indifference. Until I came out to my mother as a survivor, she was the only one that showed concern that this was happening to me. Because I wasn’t masculine, because I stuttered and stammered, and because I was awkward, I got hell from a lot of people in the places between 23rd and Ash and 23rd and G in Tacoma. It was in a desperation move that fits the prototype of Judith Butler’s definition of Gender Performativity that I became a boxer, a profession that I would have probably made my career in if not for my burgeoning addiction to alcohol.

And when, a decade and a half later, I had got recognition for my potential as a writer and returning to the literary sphere—beginning to move along “respectable Black circles,” “good white liberal circles,” and “pleasant poetry circles”—I found that some of the voices about my father had not gotten that much better. Oh, this isn’t something that should be talked about. Focus back on what a great man Bob Lashley was and the wrong done to him. Find Jesus. Don’t be too dark. Smile. Deal with it yourself, and it will be alright. We don’t want to hear how it was that bad. It did not matter that he was that bad. It didn’t matter that I was thrust into these places that were demanding me to tell my life story dishonestly. They needed me to smile. They needed me to say to them it wasn’t that bad for their entertainment liking.

By late 2011, I couldn’t do that to their entertainment liking anymore, and these groups were all but finished with me. By 2012, I was finished with living. A downstairs neighbor had done a concern check on me in March, and if she hadn’t, you wouldn’t be reading this essay. I remember coming home from the hospital with my uncle, being woozy and dopey, telling macabre jokes until I saw my uncle in tears praying to a God he never believed in. I spent the next two days delirious with guilt in bed. I felt I had hurt my loved ones in my sad boy suicide ideations even more than when I was a troubled kid. I didn’t want to die at that moment, but I didn’t want to be a coherent, cognizant being.

After three days of being essential vegetable, being sentient only to eat and go to the bathroom, I woke up one afternoon to see my mother at my writing desk. We hadn’t talked for a while, and she had taken the train up to Bellingham from Tacoma without telling me. She wore her usual earth-toned cardigan, mom jeans, and a scarf to cover the toxic burns she got when trying to throw away one of my father’s freebase kits. I had put my mother through enough as a teenager, and I was so frightened to tell her that I had put her through more. More than that, I knew her mental health was failing due to a lifetime of the trauma she kept in.

…the response was a brutal indifference. Because I wasn’t masculine, because I stuttered and stammered, and because I was awkward, I got hell…

I started to apologize, but she put her index finger over her mouth. She proceeded to tell me the straight story that she had only spent flashes touching on before. She talked to me of being 19 years old and coming from a house that wanted to give her away for adoption when she was three, how she tried so hard to fit in with her family, and—when she realized she couldn’t fit in—dreamed of college and writing as a refuge from what she knew. Then she told me of trying to talk books with English students and constantly trying to defend her right to live (“Bobby, Steve Cannon, Amiri Baraka, Chester Himes, and Eldridge Cleaver might have had differences with Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Jerzy Kosinski, and Norman Mailer,” she said “but the one thing they had in common was that they wanted women like me raped and murdered”). She told me that the majestic, hellraising, contrarian literary street fighter persona, the one I had bragged to my friends about to look cool, was one she developed to survive.

She paused, took a deep breath, stayed silent a few minutes, and put The Bluest Eye in my hand. “I wasn’t in her shoes, Bobby,” she said, “but when I read Toni Morrison, I read the first writer in college who didn’t want me to die.”

My mother passed away five years later due to dementia and complications from a fire. Her death was agonizing, protracted, and very painful. She lived to see my two published works—The Homeboy Songs and Up South—become small press bestsellers. Though she was infirmed, she also lived to see me be nominated for a Stranger Genius Award. She was also very proud that I became myself as a writer, a fire-breathing heretic with no bullshit barometer, a misanthrope who also happened to be a broken-hearted idealist, a ghetto nerd schooled in the classics, and willing to make every word work on the page. I am wild, creative, different, irreverent, and I am those things because my mother taught me. Did she have her flaws? Yes, but we all do. If you gave her a choice between a concert hall of people who truly loved her and a balcony of people across town who didn’t, she’d choose the balcony and try to convince them. It broke the two-decade bond with my adopted aunts, who wanted her to go to Seattle to be the next Elizabeth Hardwick.

Given the circumstances of her life, however, the hellish, hellish traumas she had to go through as a child and with my father, my mother was one of the most decent people I have ever known. When I needed her to be a mom, she was the best mom I could have had, and my only regret was that I wasn’t a better son when I was a teenager.

…when I read Toni Morrison, I read the first writer in college who didn’t want me to die.

Re-reading The Bluest Eye, I am still as emotionally gutted as I was that weekend when I first read it with her. I wasn’t in Pecola or Claudia’s shoes and wouldn’t be as possessive as saying I was them. But the aesthetic achievement of the book—of making the nightmare of a community that accepts abuse into art—made me feel less alone for reading it, and at a time when I direly needed to. I’m also kind of shocked that the book wears the crown of the scariest black book of its age. My momma was dead-ass-on about the books of the time: Morrison deals with haunting, haunting shit in it that moved me to tears, but it wasn’t as traumatically evil as Steve Cannon’s pedophile bestseller (Groove, Bang, and Jive Around), as Eldridge Cleaver’s commands to rape white women as a political act and black women as practice (in his essay collection Soul On Ice), or as the cocktail snuff works of Bellow (Mr. Sammler’s Planet), Mailer (An American Dream), and Baraka (who wrote almost too many to count).

What makes The Bluest Eye art, what makes The Bluest Eye even more of a powerhouse of a novel is that—in this environment—she alchemized all this agony into one of the most inventive structures I have ever read. Using broken fragments of sentences as transitions in her vignettes, and focusing on the internal cost that distress puts on Black women and how Black people hurt Black people, her structure reads like her saying, “this is the beauty and distress you are talking about, deal with all of it.”

Morrison’s alchemy is why I am crying as I write this, and crying much, much more than I thought I would at the passing Morrison. Writers before her have written brilliant books centered around Black life (Hurston, James Baldwin, and the recently departed Paule Marshall). Others have been remarkably gifted and innovative stylists and storytellers (Wideman, Edward P Jones, and the imposing, inescapable Lear of African American lit, Ralph Ellison). However, no writer did more or carried more weight as an artist to make black people free to express themselves freely, and to do so even if they were in the castes that—to this day—continue to be dammed in America. Toni Morrison’s novels made a strong case for her being the most gifted and inventive writer of fiction in the history of modern English. They also show that she didn’t want so many of us to die. And because of her, we didn’t. And because of her and my momma, I didn’t.

…she didn’t want so many of us to die.

And because of her, we didn’t.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!