“all of us play different roles in this fight for collective liberation”

Amy is joined by Leatha Udayabhanu of Essentially Awake to discuss the daily work of anti-racism, de-colonialism, and holding ourselves accountable with self-compassion.

Our Guest

Leatha Udayabhanu

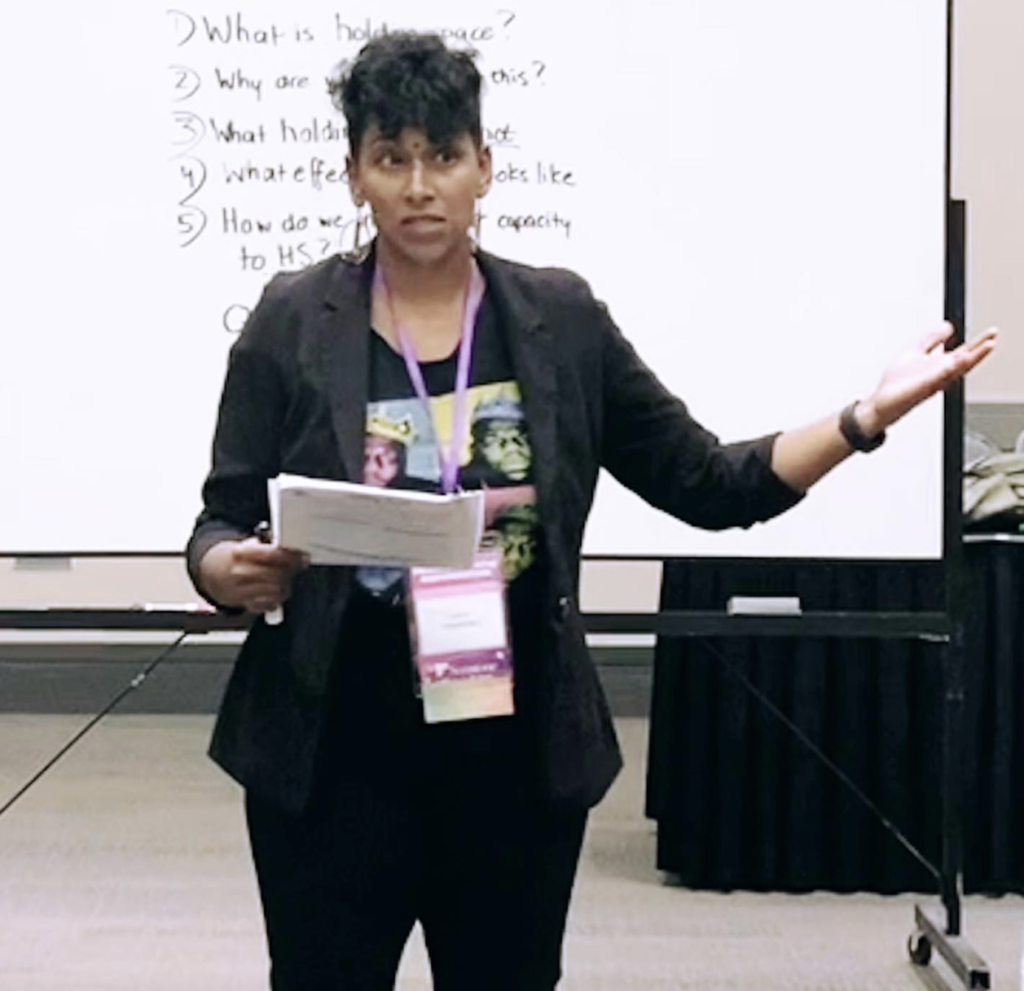

Leatha Udayabhanu is a de-colonial life coach, public speaker, and educator who guides people in healing the internalized legacies of colonization—in particular burnout, exhaustion, and shame—so they can show up in the world and fight for the collective liberation we need. She’s an expert at distilling provocative and overwhelming topics down into fundamental and simple truths so folks can take practical and sustainable action in creating a more just and equitable world.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: When I started Season Three, I was really excited to learn all about how patriarchy functions all around the world and to show up in sisterhood for my fellow women in different countries, and the solidarity with other women truly has been life changing for me, especially during our first episode on women in Iran. However, one theme that emerged from countless books and countless women that I talked to is that an even worse problem than sexism in their lives is racism and colonialism. These women have been telling me all year that if I really want to be a sister, then I need to make sure I’m engaged in anti-racist work and let them worry about their own fathers and brothers and husbands.

So, how do we engage in truly intersectional anti-racist work? One podcast that I really love that I’ve learned a ton from is First Name Basis with Jasmine Bradshaw, and I also want to recommend the work of Leatha Udayabhanu who is joining me for today’s episode. Welcome, Leatha.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Thank you for having me. I’m excited to be here.

Amy Allebest: So excited to have you. Well start today like we usually do, with me reading your professional bio, and then after that I’ll have you introduce yourself more personally. So Leatha Udayabhanu is a de-colonial life coach, public speaker, and educator who guides people in healing the internalized legacies of colonization—in particular burnout, exhaustion, and shame—so they can show up in the world and fight for the collective liberation we need. She’s an expert at distilling provocative and overwhelming topics down into fundamental and simple truths so folks can take practical and sustainable action in creating a more just and equitable world.

What a fabulous bio and Leatha, honestly, I was thinking as I was getting ready for this episode this morning, how I feel like my strength and what I bring is I’m always interested in history and like diagnosing the problems, like how we got here. And then sometimes when I’m doing a speaking engagement, when it gets to Q&A, what people inevitably ask is “Well, what are the action items? What do we do?” And I have some ideas and some things that I’m learning and working on, but sometimes I’m like, Oh. all day every day reading books and like talking to people about how we got here, but I’m not an expert in actually what to do about it. And so I am so excited to have you teach us today.

So if you can just start us out now with your personal story so that we know a little bit about who you are, like where you’re from and your family of origin and just some things that have brought you to the work that you do.

Leatha Udayabhanu: I grew up an Indian-American, South Asian, woman, oldest daughter of an immigrant family, which has its own kind of identity and kind of baggage that comes with that. And I had the experiences that I had from a really young age. When I graduated from college, I went and worked on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation for three years and I taught high school there and the experiences I had there really opened my eyes, not just about the genocide and the literal torture that so many Indigenous people have experienced on Turtle Island, on this continent, but it also opened my eyes specifically about how white people engage in social justice work, and I had a very upfront view of how harmful that can be.

So that was a really difficult, and excruciatingly painful experience for me, working with other people who, like me, cared about this and wanted to do something about what the United States government has done to Indigenous people on this land. But I had this, like I said, this firsthand view of how harmful it could be, how harmful white saviorism can be, white fragility, all of those kinds of things. That was a really intense schooling for me. And recognizing and seeing upfront that…you know, I’ve worked in nonprofits and so I have seen what that legacy of that internalized shame does and how harmful it is. And because we’re in this time and in this space where people are eager, there are so many people, so many of your listeners who are like, I want to do something, right? I want to create change. I want to take this fire in me and do something with it. And I love that. And that is exciting. And that is wonderful. And it has to be tempered with your own internal work. Because one of the things that often comes about, and you kind of alluded to this right in the intro, you said that people have been telling you, “let us worry about our brothers and our fathers, and you fight racism.” And I love that that’s the message that you’ve received because that is the message that needs to be shared. That is the message that is so important. In order for that to happen, in order for white folks to really engage in anti-racism work, you have to look inside you.

I remember being a pretty shy kid, but I spoke up about things that I really cared about, and I remember getting really upset in social studies classes from a really young age, because teachers would say things like, “Charlemagne was an incredible emperor, and Winston Churchill was one of the world’s greatest leaders,” and I was like, So, one of them killed people who refused to become Christian, and the other one starved and tortured millions of my people, right?

It wasn’t in the name of white supremacy delusion, but that’s really what the base of it was, the foundation of it. And so I remember hearing that narrative, that these people that were described as great leaders actually committed some of the world’s worst atrocities.

And so I was really aware from a really young age about how dehumanizing this was. I witnessed people being dehumanized for their caste, for the color of their skin, for their faith, for their beliefs, for all kinds of things, and that really got me fired up from a young age. So I had a lot of different experiences that brought me to this place. One of the things that I really focus a lot on is I often meet people who, especially in these last few years, and I think you can probably speak to this, Amy, because of when you came out with the podcast, right? Everything that happened since 2020, right? We’ve had all of these kind of global events. We’ve had these more localized events, but people have increased their awareness. Many through your podcast, of the kinds of things that are happening in the world, of the realities, of the legacies of colonization, of oppression, right? And people are realizing all these things and they want to do something about it. They want to take action, but so often they are paralyzed. They don’t know what to do. They’re afraid to take action or they do take action and they cause a lot of harm inadvertently.

And so I can really see now how my life experience has brought me to this place where this is what I’m really good at, is telling people what they can and need to do to actually take sustainable action. And sustainable is so important because how often does somebody get up in arms about the oppression going on in the world and they get super excited and they’re really pumped and they want to do something about it and they do one thing and then crickets. They post a black square on Instagram and then nothing. They write one check to the ACLU and then nothing. And while those things may have some impact, to really create change in this world the action that we need to take, that people who care about these things need to take, has to be sustainable. Or otherwise, what’s the point?

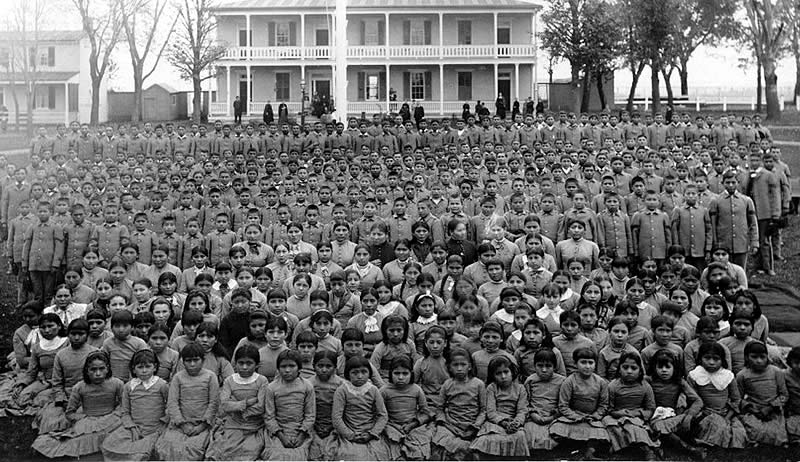

Amy Allebest: One thing that came to my mind is that you mentioned people have, sometimes, really good intentions but accidentally do things that cause harm. I’ll just share really quick. So in my classes right now, we’re in my PhD program, we’re studying Native American boarding schools. And one of the things that was so clear in a couple of the books that we read is that at the time there was a context of literal genocide, like the United States was just murdering people. And a lot of people felt really uncomfortable to very dismayed. It was primarily a Christian nation that is out of alignment with Christian values and people did know that at the time, but a lot of people were like “No, we can’t massacre them. We need to help them and save them. Thus we will put them in boarding schools so that they can assimilate and then we can save their souls and they can become Christians.” And so in contrast to literal genocide, they committed cultural genocide and they couldn’t see that there was a third option of like actually learning from another group of people and coexisting and whatever, but it just really struck this grief in my heart to see these actually really good intentioned people saying “We’ll help!” and rushing in and taking their children away from parents and putting them in boarding schools thinking—truly I think really believing, a lot of them did believe that they were helping these people—and then seeing the absolutely devastating impact of these good intentions And so maybe sometimes and maybe we can get into this a little bit later but sometimes I think that might be what is stopping people too sometimes from doing something is they’re like, I don’t want to do the wrong thing. And then 10 years later realize, Well crap, I went on an LDS mission thinking I was helping and now I feel terrible about it, just as one example. I don’t know, how do you respond to that when people ask about that?

Leatha Udayabhanu: Oh, that’s such a huge part of my work and we will dive into that, but it really is. And I love that what you shared, it is something that’s very personal to me; I’m a single mom of five kids and my children are Malayali (so they’re from my side), they are also Maori and Oglala Lakota. And so in my home and in my family, we experienced that…like my children’s great grandfather went to boarding schools and experienced the violence there, and that violence was carried on, which is what happens in every colonized society, right?

It is such a tender, painful thing to realize that the legacy is still here. People will often talk about slavery like it was 400 years ago. Actually, no, right? It was extremely recent and the legacies of that still exist. And so, you know, one thing I will say—we’ll dive into this a little bit more later—but you asked a question, like, I can’t remember exactly how you phrased it, but you said something just now about “What do we do when we’re afraid to cause harm?” and really the simple answer is there is internal work that must be done in order to minimize the harm that is caused. And there’s one more part to this, which is you cannot engage in social justice work without at some point messing up. And so rather than the goal being I’m going to enter into these spaces and never mess up, the goal needs to be I’m going to learn the skills I need to minimize the harm, to repair when I do cause harm, and to take accountability for the harm that I cause.

Those are skills that really need to be part of our kind of arsenal if we’re going to really engage in this work in a sustainable way. Because that is what happens over and over again. Somebody causes harm and they don’t know how to repair. They don’t know how to cope with the shame that they experience because of the harm, right? Or even the shame that they experience just recognizing that this is their ancestral legacy. And so people don’t know how to cope with the shame. And here’s the thing: that shame will always leak out sideways. Always, if we don’t know how to address it. And that’s so much of the work that I do. It’s showing people and teaching people how to address it.

So there’s one more piece from my personal story that I want to share before we kind of dive into the work, because it is so relevant to the work that so many of us need to do. And what that is is…a big part of what I do is I teach about burnout and exhaustion. And I teach about people pleasing. I teach about boundaries. I teach about coping with your harsh inner critic. I teach a lot about this personal journey of healing. And I do that for a few reasons. I do that one, because it is my experience. I teach about those things because I was a person who was very codependent, who had no boundaries, who had experience after experience where I was just, the martyr mom. I was all of those kinds of things and then I’ve gotten to this place in my life where I am really empowered and I have these healthy boundaries and I practice what I preach. But the specific reason that I want to share that with your viewers is this. First of all, none of that is accidental. And what I mean by that is us as a society collectively struggling with burnout, exhaustion, people pleasing, etc… is directly related to colonization. The same exact systems that we need to be fighting and dismantling and replacing with healthier, equitable systems, those same systems are why we are so exhausted and burnt out and unable to function at healthy levels. That’s not a coincidence or an accident. Those two things are directly related and that is why I wanted to share it. And that is why so much of the work I do is I teach people how to heal those internalized aspects of all of these oppressive systems, the internalized patriarchy and the internalized capitalism and all of these things that, again, lead us to a place where we are too exhausted to fight the systems, to create new systems, to uplift and serve others and to use our privilege in really change making ways. And so I think that’s such an important piece.

How often, Amy, do you hear people say, “I want to do something, but one, I don’t know what to do, but also I’m too tired to do it?”

Amy Allebest: Or don’t have time.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Yeah, “I don’t have time. I don’t have energy.” And so that’s a big part of what I do is I teach people how to have boundaries and how to heal and how to treat themselves really well, not just for the purpose of having a wonderful life, which I think is great, but specifically for the purpose of take your energy and your wonderful life and share that overflow with the rest of the world, particularly people who are more marginalized than you.

Amy Allebest: Everything you’re saying is hitting home. I don’t want to talk too much, but I’m going to tell you this thing too, because it’s like, Oh, it’s just gutting me right now. So we are helping this Afghan family that’s a refugee family. Literally, he fought the Taliban in Afghanistan and he and his family were airlifted out of the country. They were one of the lucky ones that the U.S. got out. And we’ve kind of taken them under our wing and helping…it brings so much joy to us too, to just have this new friend in our lives and we love their children so much. And I must say one thing that I struggle with is the way that they want to connect with us is to cook for us and to just sit for a long time. And I can feel this thing inside of me, partly because we also don’t speak each other’s languages and so it’s hard to bridge that. Their children are adorable and they’re learning English and they help, but it is so hard for me to just sit still and just be together and that’s what they need, actually, that is what they need. And he just texted me, the dad of the family actually just texted me like two days ago and was like, can you come to our house? And I just sat with like looking at my phone looking at the text thread thinking about all of the things that I have to get done this week. It is my primary value to connect with human beings, especially human beings who are literally in need and have been displaced because of a virulent patriarchy in this world, right? What else would be more aligned with why I’m on this earth than to make a human connection with someone who has been so harmed by patriarchal oppression? And what they need is time, and my presence of just letting the kids like do makeup on my face and letting the mom give me bangles on my arm and letting her cook for me and just sitting. Oh, it’s so hard for me, Leatha. And I could tell, Oh, this is the capitalist…I don’t have time to do the thing that would mean the very most. Sorry to take time talking about that, but what you just said hit me so hard.

Leatha Udayabhanu: I’m so glad you shared that because there’s another piece to it too. You named that what they needed was time. And here’s another piece. What they need is trust. And that is what that time and connection creates. That’s true, right? And I love that you shared that because that is parallel to so many other situations where people, again, like you, want to do something good. And this is why I have a workshop called Holding Space. And it is a prerequisite for people to take that before entering into any of my longer-term cohorts because that skill set of knowing how to hold space for other people, to create genuine, authentic relationships that are full of trust and that have depth—that’s what you’re doing when you go there and you are with them. You are engaging in that essential skill set of holding space that we, as a society and especially as Americans, we’re taught the very opposite. And so, so much of what I do is deconditioning, is helping people kind of strip away all of those layers of internalized oppression and getting to the real root of things which is depth and human connection. It’s intimacy. So I love that you shared that because I’m sure so many people can understand that exact feeling.

take your energy and your wonderful life and share that overflow with the rest of the world, particularly people who are more marginalized than you.

Amy Allebest: Well, thank you. Thank you for sharing it. Because this is amazing. That’s really, truly, literally something that I’m processing right now in my life. So I’m grateful for those tools. I need to slow myself down and build into my expectations that it’s going to take a while. Because sometimes I do, I show up and do the thing that the acute need that I see. Help the kids register for school-we go to the school, we register them. And that is the amount of time that I’ve budgeted for the day. And then it’s like, okay, I did. And then they’re like, oh, and my wife cooked this giant meal that then I know will take two hours. And I’m just learning, budget more time. Because like you, I’m so happy you pointed out, that’s what they need as much as anything else. And the trust building. And it’s just a different cultural way, like you said, Americans are not used to that, we like show up on the minute, we get the job done, and then we’re on to the next thing.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Absolutely and here’s something else too that I see in that, what you just described, right, is that as we are able to kind of heal this internalized colonization, heal this shame, what actually happens to us is that we increase in our ability to discern. Which is super important because all of us play different roles in this fight for collective liberation. You actually elucidated that right from the start because you said your role, your passion/your role is outlining the history, informing people of that, and then here you have me where my role is so different, right? Where I’m interested in the history, but my role is really about the practical and like kind of a different part of the cycle, so to speak. And that is super important because I am on the planet to do what I do. If I all of a sudden took over the podcast of Breaking Down Patriarchy it wouldn’t be the same. It wouldn’t have the same impact because that’s not the role that I’m meant to fulfill and the same thing goes for you.

And so that’s another piece to this is that as we heal those internalized pieces of oppression that we have, and we stop being so burned out and exhausted and rushed and overwhelmed, then we have increased discernment about this is the best way to use my energy, right? And we can trust ourselves that we will use our energy in the ways that are best for our particular purpose. Does that make sense?

Amy Allebest: It does, yep, that’s powerful. Thanks, Leatha.

Well, shall we dive into this list of questions that I wanted to ask you? I feel like we could talk for three hours with no guidelines and still have more to talk about and more wisdom from you. One thing that I did want to make sure that I ask is the first time we met and we were at lunch, one thing that you said just kind of as an aside, actually: you were talking about something else but you talked about how you had homeschooled your kids because you’re like No way am I going to send them to school where they’re going to learn Colonialist history and I wanted to ask you more about that.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Oh, absolutely. So my children, as I alluded to, they come from three powerful bloodlines All bloodlines which have been colonized. And so they have this powerful ancestral legacy running through their veins, you know? And I knew…you know, and I had taught, I actually taught high school on the reservation. And so I had experience in education already. We were living in Utah (which is where we live) and I did not want to send my kids to public school here. My children are actually all in public school this year, but we homeschooled for years and that was one of my main reasons because for me, I wanted my children to recognize how incredibly powerful they are, right? How unique and powerful and how they are literally the results of the love and resilience of thousands. That their ancestors resisted all of this oppression and they exist as a result, right? And so that is something that is really important to me.

And here’s the thing, when you go to school and you’re an Indigenous child and your history is relegated to, you know, week three of semester two, when your people were actually the original people of this land. That dehumanization, like I alluded to my experiences of being told in middle school that Churchill was an amazing leader and me fighting that and resisting that and pushing back and saying, “No, because if you say he’s an amazing leader, then what you’re saying are that my people didn’t matter. That the millions of South Asians who died as a result of his policies were negligible. They didn’t matter.” And so that’s what that was such a thing for me as a teacher on the res who taught Indigenous students for those three years, I saw up front and close and personal what it does to a child to not see themselves represented accurately and who they are. And I saw the power of being able to teach on the reservation and teach in a way that really honored their ancestry. And I knew my children would not have that experience in a Utah public school, and so that was really important for me. My decision was about giving my children this foundation where they knew from day one I am important. I am special. I matter.

And so, you know, I get emotional talking about this because I think it’s so important for children, I think it’s so important for them to realize who they are because and I firmly believe this: kids today they are here to shake things up, to change the way that we have been doing this They are a big part of how we’re going to create these new systems And so this is an important thing that I want to share with your viewers too, which is this, I often share this concept, but people ask me, “Well, I want to be more involved. I want to do more right in social justice.” And this is the thing I want to say: if you are a parent. that is your activism. There’s more you can do, absolutely. Recognize that your parenting is a significant part of your activism. If you can raise your children to be people who reflect, who look at themselves, who recognize the legacies that they’ve received, and who recognize who they are and recognize how they can move forward to create more equity in the world, right? That’s your activism, right there.

Amy Allebest: That’s powerful. And again, I want to recommend First Name Basis for that. That’s such a wonderful resource for parents to teach kids. It really is. And I have a question for you too. What was your curriculum for your anti-colonial lesson plans for your kids?

Leatha Udayabhanu: It was firsthand accounts. My big thing was you weren’t going to learn history from a history textbook. And so honestly, the public library. And I want to give a shout out to the Provo Public Library because over the course of over a decade, I requested tons and tons of books and they purchased every single one. They purchased every single book I requested because every book I requested was around decolonizing. I wanted my children to have books that…so it was both fiction that represented characters and people of all different backgrounds, but it was also historical accounts written not by the conqueror.

Amy Allebest: That’s fantastic. And then what a gift because now they exist in the Provo Library for everybody in the whole community. That’s incredible. Good for you. And you’re right. Good for them. That’s a success story. That’s fabulous.

Okay. Next question. Ready?

Leatha Udayabhanu: Yes.

Amy Allebest: We talked about this a little bit before, but I wanted to ask you specifically in your work with well-meaning white women who come to the work with good intentions, what do you see as maybe one of their big hurdles that they have to overcome in order to become real allies?

Leatha Udayabhanu: Okay, this is such a great question. And I would say the number one thing is white women need to face and learn healthy ways to cope with their internalized shame. So let me share a little bit more about this. I talked about and I’ve alluded to the legacies of colonization, right? And so when you think about it from my perspective, right, I have these legacies of colonization. I’ll share one, I’ll be really vulnerable right now. I struggle with imposter syndrome. Even being on your podcast. I struggle with imposter syndrome because that’s one of the legacies for me—as a woman, as a caste oppressed woman, as a South Asian woman—am I good enough? That’s one of the legacies and a lot of different people have a lot of different identities can relate to that. But for white women, there is one particular legacy that is really important to consider and that is the dehumanization that had to occur for you to be where you are today.

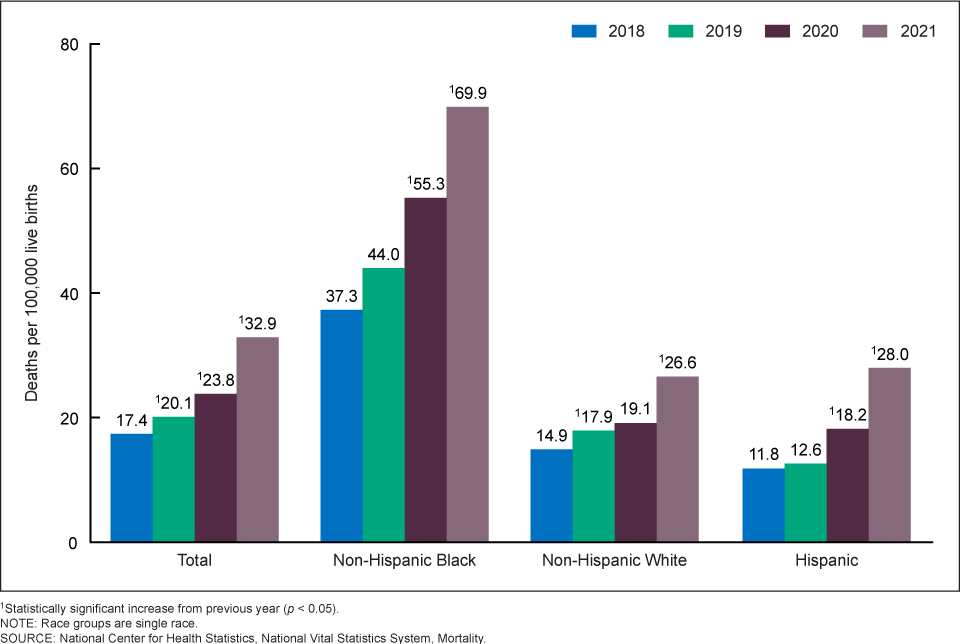

So, I’ll dive into that a little bit more. When you think in terms of epigenetics and generational trauma and how it’s passed down, we think about the trauma of enslavement, right? And how clearly the legacy of that is everywhere. The fact that Black women are four times more likely to die in childbirth in this “first world nation” that we live in is disgusting and also evidence of those legacies, of what Black people experienced in this world and in this country. And so, that’s one of the legacies.

Now, let’s take that same experience. And let’s talk about…people will say the term ‘slave owners.’ There’s another term that I think is more accurate, which is ‘torturers.’ They ran torture camps. That’s what plantations were: torture camps. What is torture if it is not ripping babies from their mothers? Beating people? Starving them? Treating them as less than human? So let’s talk about that legacy. What does it require for a human being to be that disconnected from humanity to be able to inflict those things? What did it take for a white woman–who was a mother, had her own children, had some maternal instincts and love and compassion and those things–what kind of dehumanization did she have to experience, go through, and do to other people in order to be a person who allowed that to happen around her? And not only allowed that to happen around her, but supported it and often caused the issue. Like we talk about what happened with Emmett Till and she, his accuser, she died and never paid for what she did. There’s that legacy of ‘how much cruelty can a human being inflict on another human being?’ And that legacy, I get it. It’s shameful. It’s triggering. It’s painful. Like, even while you’re listening to me talk, right? There are probably so many parts of your body that are activated right now. Like, feeling sick and has to be faced. So much of the time I see, like you said, well-meaning white people try to skip steps. You know what I think is probably an Olympic sport for most white women? Spiritual bypassing.

Amy Allebest: Oh, please explain.

Leatha Udayabhanu: So, white women tend to be very good at spiritual bypassing. “Love and light, thoughts and prayers. Let’s skip over facing the shame and really sitting with the pain. Let’s skip over that because it feels so uncomfortable.” Right? And here’s the thing. This is the thing that I want to say. Of course you’re that way. Of course you are, because we’ve been conditioned in this way. We have been conditioned to react the way that we react. And so, when we think about spiritual bypassing, and we think about why do people do it—why is it that white women in particular are so good at this—it is because you have gotten to this place and you have survived because these systems are messing everybody up, right? These systems are messing everyone up. White women are getting messed up too. So, for example, while Black women are four times more likely to die, and they have the worst outcomes in childbirth, guess what? White women don’t have great outcomes either in the United States. It’s because the system is so messed up that it impacts everybody in these negative ways.

And so, back to what I was saying, when you have this dehumanization, you don’t want to face it because instead of having a skillset of knowing how to face discomfort, most of us have the opposite skillset: we’re really good at distracting, disconnecting, sweeping it under the rug, pretending it doesn’t exist. We’re really good at that. And that is actually why I teach about people-pleasing and not having boundaries and all of that kind of stuff. Because all of those are maladaptive coping mechanisms to deal with discomfort. Discomfort comes up in the body and instead of facing it, what we have been taught to do is to disconnect, distract, to do something else entirely. And so, of course, white women are really good at this, wouldn’t you say? Really good at disconnecting and all of that.

And so here’s what the antidote to that is: the antidote to that is really sitting with and facing your shame. And in order to do that, you need to have a very different skillset. In fact, a skill set that is kind of the inverse of the skillset you’ve always had, right? So the skillset has been, I know how to sweep it under the rug. I know how to say, Oh, I don’t think they meant it that way. I don’t see color. Those are the kinds of things, right? The platitudes that kind of sweep it under the rug, but also that allow you to not look at the internalized shame. So the tool or the practice that is most needed above all that is self-compassion. That is the practice. The practice is not shaming each other, right? I always say this as an example, but it’s so true. You only have to look at any social media post about social justice that involves a lot of white people to see people engaging in this kind of shaming thing, right? You’ve seen it.

So instead of white people actually engaging in the work, some white people spend their time just shaming other white people, and then what happens? Those white people don’t want to do the work anymore, the rest of us are over here watching and we’re like, Okay, what’s the point of this? So you’re causing harm to the marginalized folks that you want to help, and all of it is because you have to deal with the legacy of your own internalized shame. And here’s the thing about it. In order to become a human being who can tolerate witnessing torture and torture is not by any means an exaggeration. We live in a country that literally lynched people; people would go to lynchings as if they were a social function, which they were. That is a legacy that you have to face and unravel. Because here’s what happens: if you don’t learn how to cope with your internalized shame, it will leak out on everyone around you. Especially the people that you’re so eager to support and help and uplift.

if you don’t learn how to cope with your internalized shame, it will leak out on everyone around you

Amy Allebest: Have you seen examples of this, Leatha? Is there like an anecdote or two that you could share of your like, Oh, that’s your internalized shame leaking out.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Absolutely. Okay. So, when we were doing homeschool co-op, there was an experience where my child called some racist behavior out. It was egregious behavior. It was ridiculous. And she wrote a letter to the mentors. And the mentors responded in different ways. One mentor literally responded by, instead of looking at my child’s points and recognizing how racist what they had done was, this woman literally printed out a photograph of her and her Black friend and handed it to my child.

So, instead of coping with her internalized shame… because here’s the thing, nobody or very few people want to be racist, right? Nobody wants to be racist except maybe, you know, if you’re a proud KKK member or something, right? Most people, especially people who are listening to this podcast or in this kind of arena where being racist…that’s like the worst thing ever. I would never want to be racist. But here’s the thing, we’re all racist. We are all racist. We grow up in a racist society, breathing in racism every single day. There is no way that we are not conditioned. We’re all conditioned, right? But when we don’t sit with it, we do things like this. Instead of that woman being able to look at my child’s words and say, Oh wow, this is hurtful. This is wrong. Let me open my eyes. Let me see. She literally pulled a “I have a Black friend,” printed out the photograph, and handed it to my child. And if you’re listening to this, and particularly if you’re a white woman and you share the identities of this woman, you might be cringing. You might be cringing for a lot of reasons; cringing because of what she did, but also cringing because maybe you’ve done some similar things. The instinct, naturally, is going to be to shame yourself. The instinct is going to be like, Oh my goodness, who does that? And so, if you’re unable to shame yourself, you’re going to shame the other people. It’s just going to be a shame storm, a shame spiral, right? And it’s not going to go anywhere. That woman who printed out that picture, she did not hear a word. She had an opportunity to humble herself, to learn, to grow, to do things differently. And instead she allowed her internalized shame to run the show.

Now, if she came to me as a client, what I would teach her and what I would show her is that the important work she needs to do is to reflect, to look at herself and to pour compassion on that woman who didn’t know better. Who learned these false ideas, right? Who internalized all of these false things. Who benefited from these systems of oppression, right? And she needs to pour that compassion on herself because this is what she did. She wanted us to soothe her. She wanted us to say, “Oh, you’re one of the good ones. You’ve got a Black friend.”

Amy Allebest: Right. And she’s also using that Black friend as a prop and like as a shield. She’s using her as an object.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Exactly. Because that’s the question I asked her. “Does your friend know that you printed out this picture as some sort of proof?” When you ask for examples, I think one of the other significant kind of examples that I see is when a white person causes—let’s talk specifically about white people, but anybody with privilege, really—when you cause harm to somebody who is more marginalized than you , that internalized shame will often result in doing things where you want the people that you’ve hurt to soothe you. You want them to tell you how good you are, how allied you are. And that’s a big part of the work that I do. And a lot of the workshops that I teach, one of the core pieces is teaching specifically white women how to unpack and disengage from their appearance of goodness obsession because white women have been taught again by these same oppressive systems that your goodness, your purity will save you, but it won’t. But it won’t. That teaching prevents you from doing the work you can do to uplift your marginalized sisters.

Amy Allebest: Okay, so I’m going to get really specific. Let’s say I am confronted with something where someone comes to me and says, “Hey, the thing you said or did hurt. And it showed a blind spot and it showed some real insensitivity to me. And this is a racialized mistake.” So what I would do—what I’m hearing you say is—maybe one step I could do is say I would think in the moment to say “Thank you so much for trusting me enough to tell me that I so appreciate you pointing this out.” And then if I need to cry about it, which I definitely would if it were me, maybe I should do that privately because then if I’m crying about it to them it can seem defensive even if it’s really not. But then it is… am I understanding right, Leatha? I mean, if I’m crying to you then of course that other person is going to feel like they then need to comfort me, right? And then they’re having to do more work. It’s putting the burden on them. So maybe I go home and I cry by myself. I examine my feelings. I get Kristen Neff’s book, Self-Compassion or her Fierce Self-Compassion, she wrote two. I mean, I’m just thinking of those two books are ones that I know of to help me maybe confront and maybe forgive myself. And then I, of course, go back to the person and apologize and maybe ask if they want to talk more. I don’t know. I’m just brainstorming. I’m like, How do we do this where we do all the work?

Leatha Udayabhanu: Exactly, that’s the piece, is in each step we need to be asking ourselves, “Am I putting labor on this person?” So I’m going to share another anecdote that will kind of summarize this, but when I was on the reservation, I was as part of a group of volunteer teachers and I was one of very few teachers of color, and I was the only one who was visibly darker skinned. And I was part of this group, and there were a lot of really difficult racial experiences, racialized experiences that I had. There was a lot of racism. There was a lot of internalized oppression. And these were teachers who were supposed to be working with these Native students. And there was just a lot of problematic behavior. Anyhow, at some point, I went to the head of this organization and I said, “Hey, this is just too much there.” And I listed a bunch of different incidents that happened, racialized incidents. And this woman’s response, she was a white woman, was to come to me—and again, at that time, I did not know what I know now—and she basically came to me and said, “I’m glad you brought this to our attention. Let’s have a fireside and you explain to everybody what is so harmful.”

Now, I was young, I was in my 20s, I did not know that what she was doing was basically asking me for a ridiculous amount of emotional labor that was not mine to expend, but I didn’t know any better and I also didn’t know what to do and I didn’t have any terminology or anything like that. So I agreed because I wanted this to stop. So there were a bunch of incidents and I started talking and I’m standing in front of this group and my voice is shaking and I’m sharing these things and I’m terrified and I start telling a story of something that happened directly to me that was very… it was a story that basically summarized misogynoir, meaning the intersection of misogyny and anti-Blackness. And I’m not Black, but I was the I guess closest thing and so that’s where it was deposited, this anti-Blackness, right? Because there wasn’t anybody else to kind of receive it.

I start to tell this story and the white woman who was responsible for this behavior in the audience recognizes herself as I start to talk. I talk to this entire time for maybe 40 minutes at this point. Painful experiences. I’m shaking. I’m barely able to articulate what I have to say. Everybody’s sort of numb and doesn’t know what to say, doesn’t know what to do. When I start sharing this particular story that this woman, what she had done, and she recognized herself, she starts weeping and wailing. And do you know what everybody does? They all walk over to comfort her. Put their arms around her, pat her on the back and reassure her that she’s a good person and she’s not a racist. Nobody spoke to me. Nobody came over to talk to me. Do you know what I mean?

So, right there, do you see in that story why we talk about the weaponization of white tears? And why your tears, like I’m so glad you pointed that out, why your tears can be received as a weapon because they’ve been used as a weapon. I just mentioned a little while ago Emmett Till’s accuser; white tears kill. And so that is so important, right? It’s that accountability piece. And you said, “What do I do? Do I go home and I cry on my own? Do I figure out, do I apologize to them?” All of that kind of stuff. Again, this is where the discernment piece comes in. When we are so paralyzed by shame, our capacity to discern is very diminished. But as we can deal with and cope with our own internalized shame, soothe ourselves, then our capacity to discern what is the best thing to do in this situation expands so much more. Does that make sense? So that’s such a big part of the work I do. I don’t tell people what to do. I invite people and guide people in connecting more deeply with themselves, compassionately, so that they can figure out what to do.

Amy Allebest: I love this. This is so important. Thank you for pointing this out.

And I’m just thinking about people who do feel like maybe they’ve been burned by a difficult conversation. And the truth is maybe someone was maybe harsher than they needed to be, or maybe they do feel like they were misunderstood, but it’s just pointing out to me so clearly: if you really care about doing this work, would you let something so small stop you? Or, like you said, the shame of Oh, I did make a mistake, or I was just misunderstood. The discomfort of that, you’re right, it can lead people to just be like, Well, fine, I’m not doing anything anymore. And then that’s not real. How much do you actually care? How much are you really willing to be uncomfortable?

Leatha Udayabhanu: Exactly. When we live a life where our values and actions are not aligned, it drains and empties us. And so if we value fighting oppression—just as an example—if we value that but our actions aren’t aligned with that, it chips away at our sense of self and then that whole piece I talked about the legacy of that cruelty and dehumanization, right? Because here’s the thing, in order to heal that generational legacy of having to be so disconnected from your own humanity so that you can engage in cruelty. What’s the antidote to that? It’s reconnecting with self, right? It’s really fully embracing your humanity. And you can’t do that if you don’t look at the pain and the shame from the legacy.

Amy Allebest: Wow, thanks, Leatha. Okay, one more question, which is connected to this, because one area that I sometimes see a lot of defensiveness from white people especially is in conversations about cultural appropriation. I’d love to get your take on that.

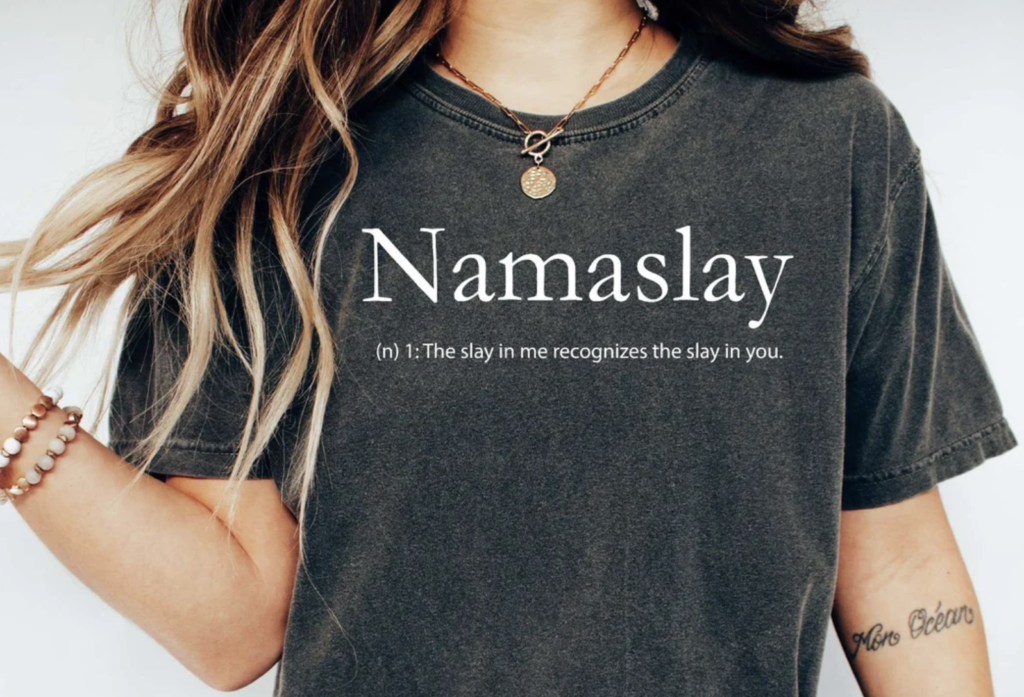

Leatha Udayabhanu: Oh, okay. I actually love talking about this, because I’m a woman of South Asian background. My culture is probably appropriated on a daily basis. Like, I see t shirts about ‘namaslay’ and whatever, you know, all the time. And so this is a topic that is really near and dear to my heart, actually. And so I will say this. Let’s talk about yoga specifically. I think yoga is an incredibly healing modality. I think that yoga in its entirety is life changing and can be life changing for so many people of any background. And I do not know of any South Asian person who actually literally thinks that yoga should be relegated to South Asians only. I don’t actually know of anyone like that. However, this is the question that I always ask when it comes to cultural appropriation and when people ask me questions about this: do you love the people as much as you love their culture? So here’s what I mean by that. You love yoga. Do you know about its history? Do you know about how it was banned as a tool of colonization. And I ask those questions because, and then do you know about what’s going on in India right now? Do you know what caste oppression looks like and how it’s being experienced all over the world? So that’s the question. Do you care about the people as much as you care about their culture?

Here’s another example: America and American music. Every genre of American music was created by Black people. People love Black culture, Black language, styles of dress all kinds of things. So that’s my question: do you love Black people as much as you love their culture? Do you fight for them? Do you care about Black lives? So that’s really what because here’s why I asked that question because cultural appropriation at its core can be another way of doing that exact practice of dehumanizing that we talked about, it might not seem on the surface as cruel. But it’s the same thing. It’s taking. It’s Columbus-ing. You know what I mean? That’s what it is. So, rather than asking questions or setting up rules and parameters like, Well, you’re allowed to take this. But you’re not allowed to take this. And you can use this, but you can’t wear a bindi, but you can do yoga. No, I don’t engage in asking those kinds of minute questions or talking about those. That’s what I really want to know. If you’re worried about cultural appropriation, that’s the first question I want you to ask yourself. Do you love the people the way you love the culture? Are you invested in learning the history? Recognizing why things are where they are. Do you fight for their posterity, do you know what people have faced in the past and continue to face? How many people out there are hugely into yoga, have changed their names to, you know, Krishna-Goddess-Whatever, right? I mean, you’ve seen this all over the place, right? I meet white people all the time that are like Oh, you’re from India. Oh, you know, whatever, right? Like you can imagine, right? The things that people say to me. And that’s the thing I want to ask them. So, do you know about caste oppression? Do you know how many trillions of dollars the British stole and looted from India? Do you call it a third world country or a developing country or do you recognize that they are a colonized nation and that it was theft that got them to this place? Do you know what I mean? That’s what I really want to know. So instead of worrying about all the minutiae of cultural appropriation, is it okay or is it not okay? Start there. Do you really care about the people? Because here’s what I’ve noticed. When people start to really dive in and start to think about the people, then all of the nuances around cultural appropriation start to sort themselves out. Because then people start to recognize, Oh, wow, this is theft. Right? They can question and ask themselves, “Am I honoring the people and the legacy and this wisdom? Or am I a thief? Am I doing the same dehumanizing practice that my ancestors did in a different form?”

Amy Allebest: This is where I, as a historian, that’s why I think history is so important. One of the big reasons why it’s so important. And I’ll just say for our family, educating ourselves—partly through the podcast actually, Season One—talking to Black friends whom I’ve talked about tons of different stuff. It’s like, there are multiple Black women that I had on the podcast and we had never talked about hair. We’d never talked about Black hair. Even just hearing their stories, but then also reading about it from Audre Lorde and like sharing in the books that we were discussing, I was like I had no idea of the history of Black women being really, truly oppressed, like sent home from school or not being able to enter spaces. I didn’t know about it. And boy, once you know that and you see a white person with dreads or you see a white person with a wig, you’re like, you would never do that once you know.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Exactly. When I see a white person with dreads, that’s the exact thought that runs through my mind. Do you know the history?

Do you understand? Cause here’s the thing. When somebody says to me, like, “I want to wear a bindi.” I’m like, “Okay, well, do you want everything else that comes with it too?” That’s what I want to know. Do you want everything else that comes with it too? So, I think that’s such a vital place to start because again, it comes back to really the root, the center of all of this work is love and compassion. This is why we want to fight oppression. This is why we want collective liberation, because of love. So we don’t want to get to love by spiritual bypassing because that’s not real; real love is accountability and that piece around holding ourselves accountable is so crucial to engaging in this work, but so many people want to skip part because it’s so painful.

It’s gross I imagine, it is gross to think of your ancestors engaging in those kinds of behaviors, right? And for me, my identities are what they are, but I occupy an unusual space in the sense that I am a caste oppressed woman, but I was not the bottom rung of the ladder ancestrally, or, for example, in the United States, I’m not a Black woman. I experience privileges because of my South Asian identity. I also experience oppression because of my South Asian identity, and I also experience oppression because of the color of my skin, but I also have privilege, I’m a college-educated woman, like, I have these privileges. And so, again, in a different way, but I have to wrestle with and face the shame that I know, for example, that my ancestors—and even some of my current relatives who are alive today—have oppressed people of other castes in an effort to make us feel better about ourselves. I get that, right? But it will not do anybody any favors for me to bypass that. I need to own that. I need to own the ways in which I experience privilege. And then I need to spend that privilege. And so, it really is so, so important. It can’t even be overstated: the biggest and most important piece of doing this work is the internal work. It is facing those legacies that we all have.

holding ourselves accountable is so crucial to engaging in this work, but so many people want to skip part because it’s so painful.

Amy Allebest: Well, I cannot believe we’re already to the end of this episode. This has flown by. And again, I wish we had more time, but Leatha, tell listeners where we can find your work so that we can really benefit from all this wisdom.

But before we go, I want to ask you maybe one more question. I know you do a lot of work with white women and I’d love to know, any just kind of last maybe practical tips that you could share specifically with white women who want to engage in the work?

Leatha Udayabhanu: So, I love this question. I had an experience a couple of weeks ago where a white woman that I’ve been working with said something to me that made me really emotional. And I wept, hearing her words. But she said to me, she said, “Leatha, I’ve been searching for somebody like you for so long.” She said, “I’ve been searching for somebody who would hold me accountable compassionately.” And that made me really emotional because that sums up what I do, it’s not just that I hold people accountable compassionately, but that is what I want you to do for yourself. That is my role, is a guide in helping people to get to that place where they can decondition, especially as white women, from all of this work, all of this kind of conditioning that you’ve experienced that’s been the very opposite, which is not holding yourselves accountable, right? And if you do hold yourselves accountable, it’s in a shame-based way, not in a compassionate way.

And so, really, at its core, that’s the practical tip that I think I would share, is start here. Ask yourselves what are the ways in which I can hold myself accountable compassionately? Ask yourself honestly, what are the ways in which I’ve kind of been expecting other people to soothe my internal wounds around this? What are the ways in which I’ve been bypassing, skipping over this, not facing it because it’s just too uncomfortable? But that’s the thing that I want you to know. White fragility isn’t real. You’re not fragile. You can do this work. You are strong enough to look at yourselves with compassion, with tenderness, and with accountability and open, honest eyes to see what there is and what could be done. You’re not fragile. You’ve got this and I can help you.

Amy Allebest: Wow, that is so beautiful. And I just want to thank you. I mean, honestly, you could be forgiven and understood for just saying like, “You people are on your own.” You know what I mean? The fact that you extend your compassion to a group of people who have as a group participated in oppression and colonization and terrible real crimes against humanity. You don’t have to do this, and it just struck me. It was very touching for me to hear you speak and just think like the fact that you’re willing to build bridges and the fact that you’re willing to be compassionate about it. I mean, that’s an incredibly generous act on your part. So thank you for the work that you do. I think it’s just beautiful. So how can people find your work, Leatha?

Leatha Udayabhanu: I’m on Instagram, @EssentiallyAwake, and I’m on Teachable. I have online courses, I do private coaching, and I also do live in-person courses for those of you who are local in Utah, or I can do it anywhere. But I would love to connect with people, those who are who feel really called to do this work. If you feel aligned and connected I just invite you to pour that compassion on yourself.

Amy Allebest: Well, again, thank you so much, Leatha Udayabhanu of Essentially Awake. Thank you for being here. I learned so much from you and just admire your work tremendously. So thanks so much for being here today.

Leatha Udayabhanu: Thank you.

This is why we want to fight oppression. This is why we want collective liberation,

because of love.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!

This episode is so valuable! I’ve heard often about how we as white people need to do the work, and I’ve been trying. And I’ve also felt stuck because I can spend so much time educating myself, trying to find what I need to change, and yet not knowing if what I’ve accomplished is actually doing the work. Leatha, you are exactly right, it has been so discouraging to think that I need to be doing more, but feeling like I’m burnt out already by the life I have and also ashamed because who am I to feel overwhelmed when I’m in this position of privilege in society. What you’re talking about here is showing me real things that I can actually do and bringing hope because what you’re teaching will make things better not harder.

P.S. How can I get the list of books that Leatha requested from the Provo Library for her homeschool curriculum?