“We have more power than we realize in this world.“

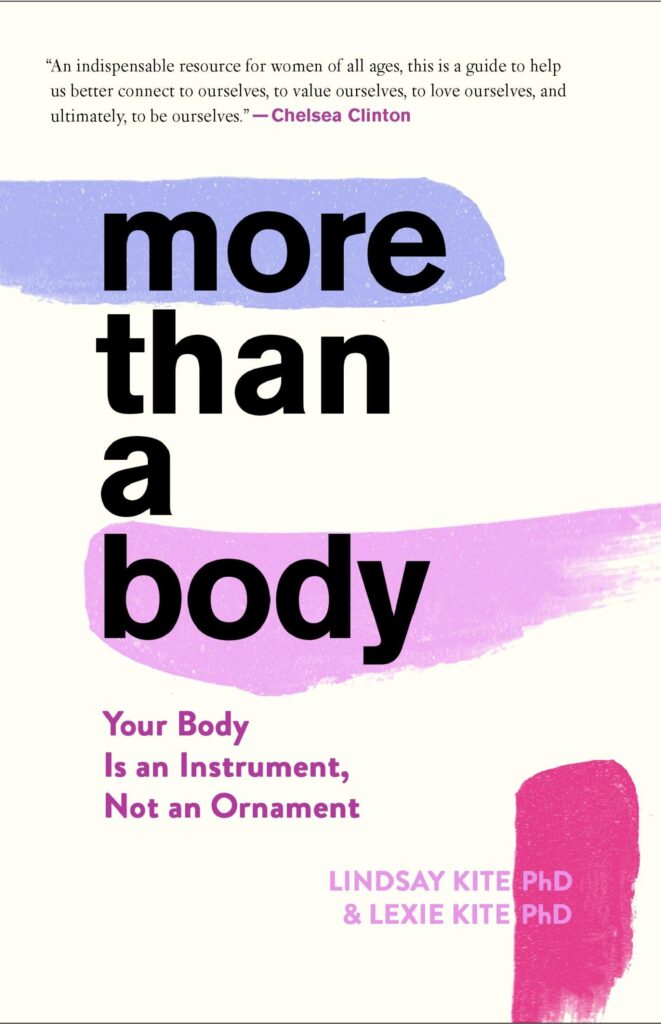

Amy is joined by Dr. Lexie Kite to revisit her book, More Than A Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament, exploring the ways women and girls are looked at, predatory practices of the beauty industry, plus how to escape the sea of objectification and come home to your whole self.

Our Guest

Dr. Lexie Kite

Dr. Lexie Kite is co-author of the book More Than a Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament and co-director of the nonprofit Beauty Redefined, along with her twin sister Dr. Lindsay Kite. They both received PhDs from the University of Utah in the study of female body image and have become leading experts in body image resilience and media literacy. Authors of numerous studies and books have cited Lindsay and Lexie’s original research and they have been featured in a variety of national media outlets, including The New York Times, CNBC, the Boston Globe, Slate, Shape, Glamour, Teen Vogue, and more.

Lindsay and Lexie help girls and women recognize and reject the harmful effects of objectification in their lives through their significant social media reach, online Body Image Resilience course and facilitator program for dieticians and therapists, their popular book (More Than a Body), and regular speaking engagements for thousands of people of all ages. Lexie lives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

The Discussion

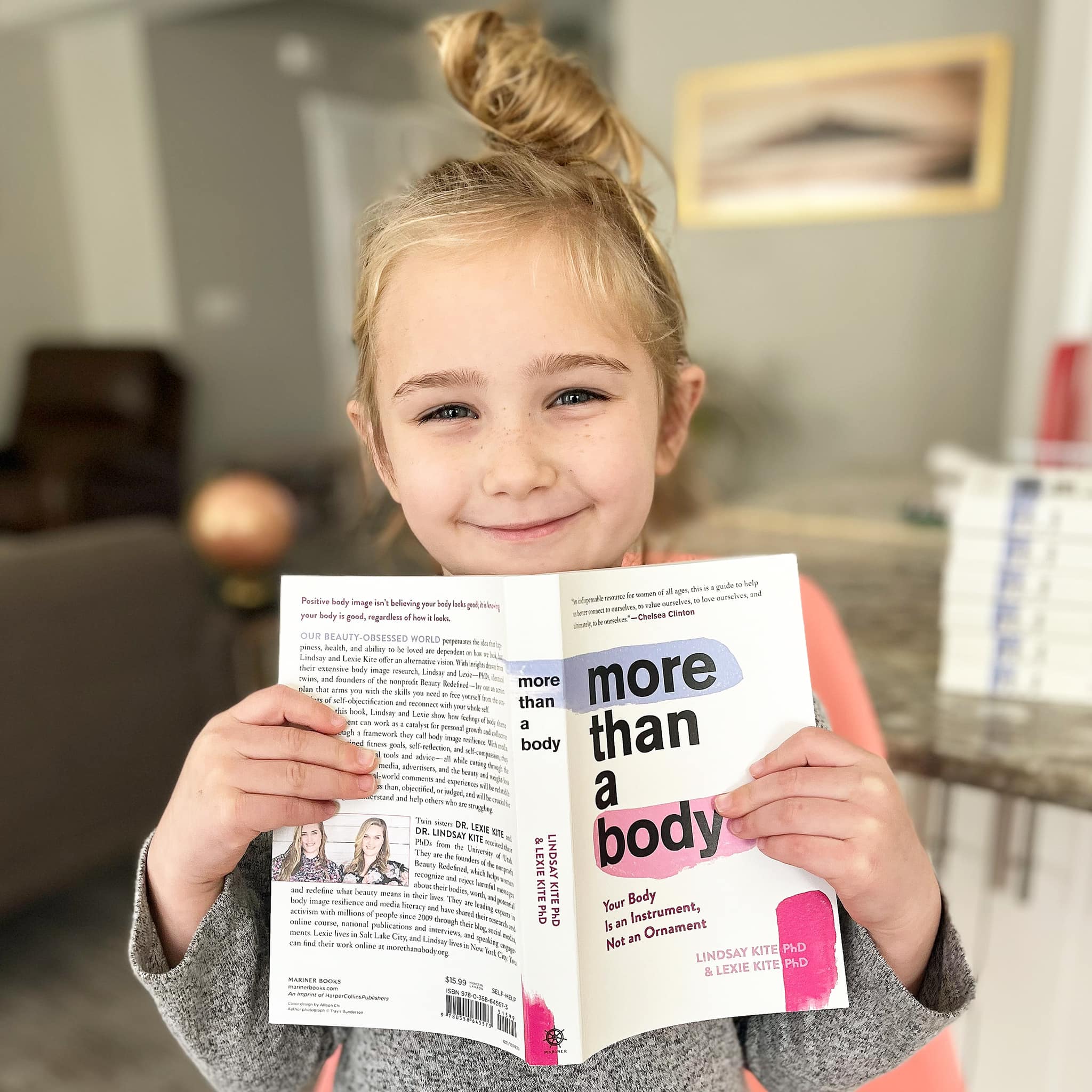

Amy Allebest: The other day I was looking through my YouTube channel, analyzing my videos to see what lighting I liked best. And as I looked at these videos of myself, I’m going to share with you some of the thoughts that went through my head, in no particular order. “Oof, what was up with my hair that day?… Oh my gosh, do I really have a double chin? I need to remember to hold my head out more… Oh my gosh, I need more makeup in that one. Yikes, I need less makeup in that one… Look at my forehead. Should I do Botox? Oh my gosh, shame on me. I don’t believe in Botox. But really, should I get Botox?… That scar is more noticeable than I thought. Should I get plastic surgery to get that fixed? I’m proud of that scar. It tells a story, and I’m ashamed I even thought about plastic surgery.” Okay, that’s the tip of the iceberg. Those are just a fraction of all of the things that went through my head as I was just trying to look at the lighting of the videos. I was scrutinizing every detail of my image. This is still a really massive struggle for me, and I think I might be living with that probably for my entire life. However, when I catch myself in this swirling vortex of self-criticism, I do have a few tools that I use to snap myself out of it, and those incredibly effective tools are from a book that I talked about on Season 2 of the podcast called More Than a Body: Your Body is an Instrument, Not an Ornament by Drs. Lexie and Lindsay Kite. I interviewed Lindsay Kite in Season 2 and I’ve always wanted to revisit the book to discuss some of the other critically important points that we didn’t have time to get to in that episode. So I am super excited to do that today with the other author of More Than a Body, Dr. Lexie Kite. Hi, Lexie!

Lexie Kite: Hi, Amy. I’m such a big fan and so happy to be here.

AA: Oh, I’m such a big fan of you and I’m so happy that you’re here with me, too. I’m really excited for this always relevant conversation. Dr. Lexie and Lindsay Kite are identical twins, co-authors of two books, More Than a Body and The Official Workbook for More Than a Body, and they are co-directors of the nonprofit Beauty Redefined. They both received PhDs from the University of Utah in the study of female body image and have become leading experts in body image resilience and media literacy. Authors of numerous studies and books have cited their original research and they’ve been featured in a variety of national media outlets for the last fifteen years. Lindsay and Lexie help girls and women recognize and reject the harmful effects of objectification in their lives through their books, their significant social media reach, and speaking engagements for thousands of people of all ages. And again, I just have to say, thousands of people of all ages, including me, I cannot overstate how valuable your research and your work has been in my life personally, Lexie. I just want to thank you personally for it.

LK: Thank you. It means the world.

AA: Well, I’d love you to introduce yourself more personally now, if you can tell us kind of why you are who you are, what got you to where you are today in your work and in your personal life. What makes you you, Lexie?

LK: Yeah. Big question there, still working on that at now 39 years of age. Outside of my professional endeavors with my twin sister, Lindsay, who lives in Manhattan and I live in Salt Lake, I have another professional endeavor. I work at the University of Utah. I oversee alumni and help raise money, and I love my work there and really believe in higher education. It’s where Lindsay and I did our master’s and our PhDs and it holds a special place in our hearts. It has allowed us to do this public intellectual work that I know you value and do as well.

AA: I do.

LK: I am, at the time of this recording, due to have my third baby in just a few weeks.

AA: Congrats! So exciting.

LK: Oh my gosh. Yeah, we’re like a month away at this point. This is my third girl, and as you know, I’m very partial to girls and feel like I’ve been training for this my whole life. I have an almost nine year-old daughter, a five year-old, and now a new little one on the way. Outside of that, Lindsay and I write in our book about our journey to becoming body image experts. And it all started as identical twins that grew up and grew older in the ‘90s in a diet-intensive, looks-intensive, sexist world that, you know, we all grew up in, whether it was in the 2000s or the 1900s. And we had a wonderful, loving family and community and culture and an absolutely wonderful childhood, and yet could not escape all of those really objectifying ideals that hit all of us, regardless of how we look or how we think we look. So, Lindsay and I growing up were very identical. We were constantly looked up and down and compared. And when you’re being compared or comparing somebody, there’s always a winner and a loser, no matter what, even with the most minute of differences, and so we grew up not only seeing other people look at us and judge us and try to figure out our differences, but we learned from an early age to do that to ourselves, to become our own critical onlooker, to have that voice in my head that would say the same things people would say about me out loud, even more negatively. We all learn to grow up in that way.

In college, when Lindsay and I took a required course in media literacy – and we took different sections of the same course, trying not to be such twins – and I remember hearing on that very first day, my amazing feminist professor talking about how we come to internalize profit-driven ideals about ourselves. My heart pounded faster and I thought, “Okay, so the dieting I started when I was 12, the ways I have bought that I could never be loved because of how I appear, maybe that’s not natural. Maybe I learned that, maybe I can overcome that and help other people to do that.” Lindsay, of course, had the identical experience to me, and that began a lifetime now of 20 years of doing this work, culminating in our PhDs and in our book More Than a Body, which has been the central place we put all of our ideas around objectification to help people overcome it on their own.

But I just absolutely love the way your work in breaking down patriarchy speaks so beautifully to the work of breaking down objectification, because I see them as completely intertwined and interlocking. You do not get the internalized objectification so many of us live with, of thinking about ourselves as only bodies to be looked at, judged, fixed, used — you do not get there without patriarchy, without growing up with an internalized heterosexual, male perspective of your value, your worth, and your power. So, I think that our work complements each other so beautifully. And your work, for me, I’m talking a lot, but I do want you to know that your work has been so central and pivotal in helping me to be able to articulate things that I’ve felt for so long. When you wrote that “Dear Mormon Man” essay in 2016 or so, that was when my first daughter was born. And for years prior to that, I had been disentangling my spiritual and religious beliefs from patriarchy that had been trying to make sense of that and reconcile it and couldn’t do it. And that all came to a head when my daughter was born in 2016. And 2016 being this time where I thought we were going to have the first female president, ushering in my daughter and thinking through, I get a little bit emotional thinking through not just raising myself in that world, turning 30 and trying to navigate sexism and patriarchy that I knew was so bad, so harmful and wrong, but then having to lead my daughter through that too. So reading that essay, it broke me. It put words to the things I’d been saying for years, the harms I saw in patriarchy that I could not reconcile and would not stand for anymore. And I sent it to my husband. In the years since, I’ve sent it to everybody I know and love, everybody I talk to who is going through that journey that I had done 10 years ago. So, your work is so powerful and I’m so happy to talk to you today.

AA: Thank you so much, that means the world to me. Thank you, Lexie. Well, let’s start off our conversation that’s going to be focused on the book by digging in deeper to what you just introduced us to, which is objectification, self-objectification. And I do agree that these things are interlocking, and for me discovering your work helped me put words to things that I was just trying to untangle within patriarchy. I think I encountered this concept on a very shallow level first through art history, through John Berger’s essay about how women are looked at and then we internalize that objectifying male gaze. That’s kind of what I introduced the episode with, is like I’m looking at the videos as if I were, well, and I kind of am, and that’s the hard thing about photos and video is we are objectifying ourselves. But anyway, introduce us to self-objectification. Where does it come from? And you already kind of linked it to patriarchy, but is there anything that you want to say about that?

LK: Yeah, absolutely. There’s this one quote from our book that we had shared on social media prior to publishing the book that kind of encapsulates what we’re talking about when we talk about this idea that from the time little girls are young, we decorate them in ways that we don’t for little boys. We prioritize pretty over practicality for them. When they’re climbing up the stairs or the tree, and they’re wearing little tights and frilly dresses, and have earrings in that might snag, and bows that fall down over their eyes, and their clothes are tighter, and they don’t have pockets, and they don’t have reinforced knees, and that’s when they’re two and one, you know? It continues on from there in these ways that we ask girls to prioritize how they look in the world over how they feel inside their bodies as their own. We internalize this objectifying perspective and it leads us and everybody else in the world to objectify women in ways that we don’t allow them their humanity in the same ways that we allow boys and men to have their humanity, to be full, thinking, breathing humans with power, regardless of how they look a lot of times. So I want to read this quote from our book. It’s just a little excerpt:

“Girls learn that the most important thing about themselves is how they look. Boys learn that the most important thing about girls is how they look. Girls look at themselves. Boys look at girls. Girls are held responsible for boys looking. Girls change how they look. Boys keep looking. The problem isn’t how girls look. The problem is how everyone looks at girls. Solve the problem by teaching everyone that girls don’t exist to be looked at.”

Now, that is an excerpt that I think we were talking about in terms of modesty and the sexual objectification of girls and women, but is so much more broad than that. And your listeners are experts in objectification at this point, and in breaking down patriarchy in the most literal sense. But I think that for each one of us living in a body, for those of us living in a female body, just like you introduced in this podcast, none of us are immune from that internalized gaze that we have been taught from a very young age. It’s patriarchal. It’s a heterosexual male gaze that we turn upon ourselves. Not even so much in the fact that it is your husband or a man in your life that is literally pressuring you, although that is often the case. But more so, it is that own inside critical onlooker that you have learned to view yourself through. When Lindsay and I were doing our initial doctoral research years and years and years ago, we asked people this baseline question, “How do you feel about yourself? Tell us how you feel about yourself.” And we would get a completely different answer to that question. They aren’t talking about how they feel about themselves. Girls and women respond by their worst fears of how other people feel when they look at them. They say things about the outsides of their bodies. “Oh my gosh, I can’t believe my body has changed this much in like two years. I can’t go to that high school reunion. That would be the most embarrassing thing. Ugh, does my husband or boyfriend look at me and just think I’m so disgusting? I’m not going to get that promotion because of how I look. I cannot believe that I am out right now with this acne.” A million ways we do this to ourselves, even on days when we feel good about ourselves, we’re thinking, “I left feeling good, am I still good? Do I need to adjust? Do I need to make sure I’m powdered up and adjusted and everything is in place?” It is just a constant soul-sucking thinking about how we appear.

the internalized objectification so many of us live with, of thinking about ourselves as only bodies to be looked at, judged, fixed, used — you do not get there without patriarchy

And I connect this so closely with patriarchy that we have all grown up with, or in some way we’re tangential to. Because in spaces and places where men primarily have the power, the power to lead, to speak, to discipline or promote, to control finances, to do any number of things that are under this umbrella of power. In places where men have that power in much greater majority than women, then women’s bodies and our sexuality, our appearance, become our primary form of value. We, by default, become objectified because that is how we are useful to men, how we prove our use, whether it’s just looking pretty so that we’re treated a little bit better, or beyond. Men and women cannot be on equal footing when patriarchy is the ruling power. We try to help people understand that if you’ve internalized male as default and female as other, female as sexual and decorative, and male as everyone, then that just reinforces this patriarchal norm that exists everywhere, in the children’s books we read that are primarily “he” pronouns that I always switch. In the top 500 kids’ movies, still, the male characters greatly outnumber the female characters and speak for twice as long as the female characters. And that is improving over time, but when it starts with kids’ media and then moves all the way up to the many ways women are sexualized and nude or near nude when the men aren’t, and how the camera pans up and down bodies, and on and on, you can see how it looks so normal and natural that of course we are the objectified other. Of course I gain my power and my happiness, my feeling of normalcy and femaleness by decorating myself and constantly thinking about how I look instead of how I feel.

AA: Amen. And hallelujah. Yeah, it’s true! It’s true. And again, listeners are going to be like, “Yes, all of that!” I just have to say here, and I’ll say it at the end too, if you don’t have the book yet, go buy the book. Because I reread the entire thing just to prepare for this episode and was so glad I did because it does help so much. You just nail everything. I want to point out something else that you said about being judged for appearance, and you say in your book that it’s true that men are judged for their appearances, too. And if you talk to, for example, short men and the bias that they experience in the world, that’s real. And there are certain things that are prized in men’s appearance and not. But you say that men who don’t fit the appearance ideals “are much less likely to face the repercussions women do because our culture values men far more than their bodies or their sexual desirability. Their looks are just one part of their identity and rarely the most important part.” I’m really glad that you point that out too, that it does exist for men, but it’s not even close to the penalty that it is for women to not meet the ideal.

LK: Oh my gosh, if you think about all the examples of the ways that women are asked and coerced and begged to think about how they appear. Just running through these examples, the way women are told they need to “keep it tight” for their husbands. You know, men are “visual creatures.” Is that true? Or are women also visual creatures in all of the same ways and more? In stereotypical ways where we make sure we’re dressed well and that our male partners are too, that our house is beautiful. All these ways, of course we’re visual! It’s so silly to think about that. The way that women and girls get told to put on a little lipstick, or if you want to be in a professional setting, you do need to wear heels, and you do need to wear some makeup, and I’m sorry, that’s just part of the job in this professional setting. Or that when you are going to a formal event, a dance, a school dance, whatever, girls are still required to wear dresses and then have to make sure that the appropriate amount of skin is showing, but skin still must be showing if you’re wearing a dress. Oh, just so many ways. I think about pregnancy and childbirth, the fact that while for me, pregnancy is always helpful for my body image, it really brings home our mantra, “my body is an instrument, not an ornament.” My body is instrumental right now, and I think that for many pregnant women it goes both ways. For a lot of pregnant women, they feel like they can take a break from the objectifying ideals because you don’t have to have a flat stomach and you’re doing this work that you’re not in a lot of control over and so you’re valued still for your body doing a thing.

AA: Yeah.

LK: A different thing that’s not sexual. And on the other hand, it also propels you into the spotlight because people are looking at how your body is changing and commenting on it and they want to touch your belly and all of the ways. I think about all of the ways that the anti-aging industry is for women and not for men, and the eyelash industry is for women and not for men. They just are not asked to think about their pores, the length of their eyelashes, the thickness of their eyebrows, how pretty their armpits are. Oh, it goes on and on and on.

AA: On and on! And you write about this from head to toe, and we won’t go through all the body parts, but literally, even some things that I haven’t thought about, that I’m like, “Oh yeah!” Coloring the hair, the eyebrows, the eyelashes, the neck, we talk about the chin, and as we age, the wrinkles, really truly! Let alone the boobs, and the tummy, and the hips, and the thigh gap. It is literally head to toe. And with fingernails and toenails, and the whole thing. Anyway, yeah, it is exhausting and it takes up so much of our precious time and energy and life force and it is, it is actually really tragic. What a tragic waste.

LK: It’s tragic. And you know what? We talk about it, and we have it in the beginning of the book and in the beginning when we’re doing speaking events, we bring out the literal objectification of women from head to toe. Not to discourage people, not to just make people feel so hopeless that they must succumb to these ideals, but to say that we have got to rise up and rebel against a system that was never going to serve us. You can play by the rules of objectification. You can play by these patriarchal rules. And what will it get you? It will get you power that is handed to you by people viewing you or using you that can be taken away, and will assuredly be taken away, just as easily. It’s why as women age, they start to feel invisible, and we tell those women and have spoken about it a lot, “If you feel invisible as you age, you might want to reverse, flip that narrative on its head, and congratulate yourself for graduating out of a system that valued you for your sexuality and your body at the expense of your humanity. As you feel invisible, you actually have more power. You have more spending power, most likely. You’re older, you’re wiser, you’ve been through it, you are less inclined to be swayed and pressured by the ideals than you were in your teens and twenties and even thirties. Maybe it is the perfect opportunity to opt out, to prove your privilege and use it, to not succumb to every ideal, but instead to push back, to organize, to advocate, to help people understand that while you might not be getting all the the– whether you do or not, I’m not going to blame you, but if you don’t, if you spend your money and your energy and your pain in other ways than getting your face fixed and your body fixed at all times, you can prove to yourself and everybody else that you are still you, that you are powerful as you are, that you have work to do, and maybe you don’t turn the heads of the people you used to. And you learn to realize that that was always going to be fleeting power, that was never going to be power that did much more than help you feel like, ‘Huh, maybe I do look okay today. He was nice to me today. They were nice to me today.’” We have more power than we realize in this world.

AA: Wow, Lexie. Thank you for that. So powerful. I want to put you on top of the rooftops and hand you every megaphone to teach the world, haha. One thing that you mentioned a little bit earlier, you mentioned the word “profit,” and that a lot of these kinds of interventions that women do, and even social media presence and a lot of campaigns are still about profit. Can we talk about the beauty industry specifically?

LK: Yeah, what a powerful industry. We talk about the beauty and much of the weight loss industry as part of the same deal. When I’m talking about the weight loss industry, I’m talking about the industry that preys largely on women, and you can see it on billboards and everywhere else. The commercials during daytime TV and on radio and everywhere that ask us to confuse our health with our appearance and specifically with thinness. That is a beauty ideal. That is not a health ideal. That is how we look, not how we feel, not what we can do. That beauty and weight loss industry is a multi-multi-multi-billion dollar industry growing every year. Even when economies are doing bad, the beauty industry is doing really well. It is immune from any economic impact factors or complications, the industry is so powerful. It’s infiltrated every area of our lives. It’s even infiltrated body image interventions where companies, many companies, like Dove, many others have co-opted empowerment for profit. So they say, “You are so beautiful. You have no idea how beautiful you are. If you knew how beautiful you were, you’d get out there and change the world” while they’re selling you the products to enhance your beauty. It’s these companies that co-opt the message, but if you look beyond the surface, if you look beyond what feels like a really empowering message, oftentimes it is a facade. It is only used to sell you more products and services.

And some of that can be seen as progress, you know, I think it’s helpful to remind people how valuable they are. But so many of these messages, if you dig in just a tiny, tiny bit, you realize they’re still reinforcing beauty. They’re reinforcing objectification as the primary form of power and value we have. I want to just shout about it because it just drives me insane! We want people to know that if you’re hearing these messages that are all about girl power and “you have no idea how beautiful you are, you look so good,” whatever the thing might be, listen to that. Are they still talking beauty? Are they still talking looks? If that was a message that was delivered to boys and men who also have body image issues, who also have self-esteem issues, would it land or would they laugh? “Boys, you are so handsome. If you had any idea how handsome you were, you guys, you just go out and change the world. You wouldn’t be worried about how you’d look.” No, we laugh at that because we raise boys to believe they are more than their bodies. They are more than how they look. It sounds silly, and yet we believe that we must operate within this system, this patriarchal, sexist, exhausting system that tells us that in order to be happy, we have to look good. In order to be healthy, we have to look good. Look good according to whom? Those ideals are changing constantly. They are in a constant flux because it is supposed to be and designed to be out of reach for us.

AA: Mm-hm.

If you look beyond what feels like a really empowering message, oftentimes it is a facade.

It is only used to sell you more products and services.

LK: We’re still seeking these mirages. One thing that we really want people to know, that we reinforce so much in our book and in our work, is that focusing on the appearance of your body will not heal your relationship with your body. It will reinforce that you have to think about how you look. There are a million messages that tell you that if you fix this thing, you’ll fix your life. And it’s not true, and we all know that. If you think back on the times you were the thinnest, or when you were younger, or when you had a lot of attention from the opposite sex, or the same sex, whoever you’re attracted to, when you really look back at those times, I think most of us can realize that we weren’t necessarily our happiest. We weren’t necessarily treating ourselves the best. I know I wasn’t. At my thinnest, the times where people were complimenting me the most, that was my least healthy. I am much more healthy at a much higher weight, working out and feeling so good about working out for non-aesthetic reasons, doing it in my third trimester of pregnancy and feeling so good about it, haven’t weighed myself the whole time, way fatter than I’ve ever been, super happy. These things are all possible, but you’re not going to hear that in a profit-driven world driven by an industry that banks on the fact that women are the primary spenders in every household, that we control how funds are spent, and so they target us from the beginning of our lives to make sure that we’re thinking about how we look instead of living inside our bodies, the only bodies we’re ever going to have.

AA: Yeah, that’s powerful. This is reminding me of The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf. And I remember reading her talking about how Betty Friedan had pointed out that the ad executives were purposely exploiting women’s insecurities about how clean their homes were and their laundry and their children being clean. And like, “Ooh, if we can make them feel really insecure, we can get them to buy cleaning supplies and cake mixes and all the stuff that they’re feeling insecure about.” And like you said, you never want the woman to be satisfied, you have to keep them insecure so they’ll keep buying stuff. And then Naomi Wolf later pointed out that it’s shifted. They are not getting women to spend as much money on floor wax or microwaves anymore, so they have to make us feel insecure about our bodies, our faces, our hair, all of this stuff. And that has continued unabated in the decades since it was written. They’re just exploiting our insecurities.

LK: I mean, what an incredible idea, you know? And the thing is that it is incessant and never-ending, and we can rest assured that as long as we live, advertisers and media executives and companies will continue to find new ways to exploit us, to change the ideals when we think we’re close because it is designed to be out of reach. We desperately want people to know that as you are coming back home to your body, as you are developing what we call “body image resilience,” the ability to be resilient against all of the objectifying ideals that are thrown at us from every angle, the goal isn’t to never think about your body. The goal isn’t that you are going to just feel so good, that the mean thing you think about yourself or you deciding to go on a diet or whatever the thing might be, that you’re immune to those things. You are not. We all live in this world. We are all coping with the shame and the shaming messages that we’re getting consistently. The goal isn’t to be immune to it. The goal is to be able to flex your muscles for body image resilience to become stronger so that things don’t hurt so bad. So that the things that ten years ago, if your grandma would have said that thing about how you looked you would have immediately made plans to fix the thing in whatever way, to never wear that outfit again when you’re tagged in a photo you don’t like, to go on a diet because, “Oh my gosh, these jeans don’t fit that I just wore.” All the things we do, the plans we make in the name of trying to cope with our shame and our objectification.

The goal is that instead of resorting to those really harmful coping mechanisms that we all learn to cope with, those don’t serve us. Instead, we resort to coping mechanisms that serve us, that allow us to sit back when we’re triggered in the moment, no matter what the thing is, big or small, and know that we are human, we deserve our humanity, we deserve to be home in these bodies that are nobody else’s but our own. So, how do you do that in the moment? How do you come back into your body to be able to value it as yours first, to not punish yourself, but to be able to cope with the shame in the moment, and then flex those muscles so that the next time that same disruption happens in your life, it’s easier? Over time, things that used to throw me for a loop, a comment on the internet, my weight, the pores on my face, those things… Eh, we’re good. No, we’re fine. And it just takes flexing that muscle. We want people to know that this is not a hopeless endeavor. This is a happy and hopeful endeavor. It’s an individual endeavor. It comes from the ground floor. Every single one of us that reclaims our bodies as our own, as an instrument for our own use, not an ornament to be admired. We rise up, we help everybody else around us do it, and that is the change we’ve seen over the last many years of doing this work that I know continues to be possible for us.

AA: Can I have you dig in a little bit more specifically on the methods you use? So when I experience a body image disruption, for example, if I’m looking at videos of myself, or maybe I see a picture that my husband took and he texts it to the family group chat, and I’m like, “Oh, it’s so bad” and I can feel myself plummeting to the depths of despair, what do I actually do? Because I know, like you said, we have the mental patterns like, “I’ve got A, B, and C,” what are the ones that you talk about in the book, Lexie? Fix, hide, those are some of those things.

LK: The primary coping mechanism that most people use when they face a disruption to their body image, which is big and small, it’s a photo, it’s a comment, it’s trying on jeans in the dressing room, and your body changing, pregnancy, weight loss, aging, the things that are just inevitable, they happen to us all, these are all regular disruptions to our body image. And what we found in our research is that especially girls and women cope in one of two harmful ways: they sink deeper into shame through really harmful coping mechanisms that numb you in the moment but hurt you in the long run. So we’re talking disordered eating, starving, binging, over-exercising, punishing yourself through burning calories that you just consumed. It happens through self-harm, which especially for young women is on the incline every year, on the rise. It happens through drugs, even prescription drugs, things you abuse to feel numb, to escape the shame. But when you come out the other side a few minutes later, you don’t feel any better. It’s never served you. And many of us have coped in these ways and realize that it doesn’t serve us.

The other extremely common way that people deal with these kinds of disruptions to your relationship to your body, to your body image, is through hiding and fixing. We hide ourselves, literally. You stop raising your hand in class. You don’t volunteer at your kid’s school. You can’t wear that thing that you thought you wanted to wear that seemed so cute on somebody else because you saw yourself in that reflection. You opt out. You stop working out. You don’t want to go to the gym or be outside because you don’t want people to see you. You have your partner take your kids to that event because, “Ugh, I don’t look good today. I don’t want to.” We opt out of our lives. We don’t want to speak up because we don’t want people to look at us while we’re talking. We don’t do interviews. We don’t get the job we want to have. And on and on. I could name a million examples. We’ve all been there. The other way is the fixing we’re talking about. Fixing happens, again, in big and small ways. It’s plans for cosmetic surgery or cosmetic surgery. It’s procedures. It’s how much you spend on your face and your body. We don’t want to vilify these things because we’re all doing it in some way. I just had to explain to my daughter that mascara is one of those things that is super sexist, that we don’t ask men to wear, and I’m wearing it. And explaining that we all opt into some sexist stuff, and this is that thing that I’m doing. And then I don’t wear it around her, too, so she knows I’m still me, and I know I’m still me. I’m opting in to some of that stuff.

AA: Me too.

LK: I’ve also drawn the line further back than some people would. I don’t want to do anything painful, I don’t want to do anything invasive. I’m not going to, just because of the work that I do. But I know and love people that do. I would never judge. I know what it’s like living in this world. So I think that for every one of us, we cope in these ways, but over time we realize that the things we’re doing to cope aren’t getting us to a happier place. Sure, you might fix a thing, but it kicks the shame to another thing. Or you get so much attention about that thing that it makes you feel worse about yourself and your body image because so many people are paying attention to that thing and not you. In so many ways, it just reinforces our own objectification as we’re trying to break free from objectification by just feeling okay. So, the way out is through body image resilience. Body image resilience is a continuous process. It’s not a one-time thing, it’s not a one-time fix. It’s a lifelong, but totally achievable, practical, and absolutely revolutionary process to help you get back inside your body every time your body image is disrupted. The body image process is, like I said, built on this certainty that you are going to face disruptions to your body image regularly, and that’s okay. The goal here is that as you face the disruption, you can name it. You’re not just swallowing it, it is not your fault, it is not just a result of living in a female body. You’re going to name it, you’re going to call it out. “This is not a natural way of being. I don’t have to punish myself for feeling this way. I learned to feel this way. This is not who I am. I learned to feel this hate.”

It’s the nature of the human body, especially in a sexist, objectifying culture that places way too much value on how we appear, for us to succumb to these objectifying ideals and shame so much of the time. But the goal is to be able to call it out so that the shame you feel is a catalyst, a spark. Instead of coping in the ways you used to, the second the shame arises, you think about it, you feel it in a new way, and it is your opportunity to make a new choice to come back to your body as your home. In many of those instances, your husband sends a group photo of you that, oh, been there, done that. Photos are especially triggering because it is a literal, objectified picture of you and it takes you out of living in your body to seeing your body. And I’m triggered by those things too. I have been there. I wrote about one of my experiences in the book of my favorite thing being swimming, and my husband taking pictures of me swimming with my daughter and I was looking at his camera on the way home and just deleted all of them on the drive. Yeah, we went to Hawaii and I did delete some photos this time, but I wasn’t deleting photos that I was like, “I look so fat. He can’t look at me looking so fat, or he will stop loving me.” It was not that at all. This time it was just photos that we weren’t going to print.

AA: Yeah, yeah, that’s great.

LK: It wasn’t this shame that just stunted me in every way. Because I have faced this disruption before. So when you get the photo you don’t like, when you see your own photo or video you don’t like, come back in your body. Literally take a second to yourself to breathe, to feel your senses, to feel your lungs, your butt and your feet, or your feet on the ground. “What can I hear? What can I smell? What can I touch?” Get back in your body, literally. And then make a new plan. While your mind immediately races to the ways you’ve coped before, the diet you’re going to go on, the workout you’re going to get back on top of immediately out of punishment and not joy, instead, you’re going to breathe and you’re going to think about your privileges. Is your partner going to leave you? Do you feel like you are going to be alone forever with no love in your life because of how you look? These are shaming messages that you have internalized. It is not true. People love you no matter what, and if they leave you because of how you look, my goodness, thank you for leaving. What an unhealthy place to be in, a place that would cause you to hate yourself.

So whatever you can do to get back inside your body, and then you make some new choices for your life and your environment. Do you need to change what you’re looking at on social media? Do you need to retrain that algorithm for what serves you, what doesn’t hurt you? I do not look at anything that causes me to self-objectify. If I’m scrolling on TikTok and I’m seeing somebody using a filter or talking about their cosmetic surgery work or whatever the thing is, swipe. If you don’t give the algorithm your time, it learns that those are not things you want to see. We know that the algorithm prioritizes ideal-looking bodies and faces, which is racist, sexist, objectifying in every way. Swipe quickly. Mark on Facebook, on Instagram, “I don’t want to see this anymore.” Report, block, whatever you need to do. Train the algorithm to serve you. Spend less time on the screen. Help your kids to do exactly the same thing. Don’t talk about bodies. Don’t talk about your own or others’ bodies. Use your body as an instrument. Set your fitness goals for ways to move your body, to increase your endorphins, to increase your strength, that don’t have anything to do with aesthetic goals. We have a million more of these in our book and in our work, but many of them are intuitive for each person. It is the ability to think, “I can’t punish myself. I don’t deserve this. I am more than a body. How can I treat myself well, even though I’m experiencing this pain right now? How can I use this pain as a catalyst for my growth and not just to cause me to stay in that same cycle, where I’m just succumbing to the patriarchal, sexualized objectification cycle that I’ve lived in my whole life?” How can you get out of it and get back home?

People love you no matter what, and if they leave you because of how you look, my goodness, thank you for leaving.

AA: Yeah. I love that you keep referring to home. That was my big takeaway from rereading the book that kind of went past me the first time. I grabbed onto so much the first time I read it. And this time I noticed that you write, “Your body is your home, your ultimate comfort, your respite, yours and no one else’s.” That has been like a mantra to me since I re-read it a couple of weeks ago, that when I do find those disruptions, I just bring myself back home, and hug myself. And I don’t know if it’s too personal, Lexie, but you did write it in the book, I guess, but I don’t know if you want to share it today. You did talk about a really beautiful experience that you had that really deeply soothed a body image disruption that you had, and I’d love to invite you to share it if you’d like to.

One thing that really helps me, which is similar, is thinking about myself the way I view my own children. My babies, when they’re babies, just celebrating them because they exist and just their essence and celebrating their tiny little fingers and their tiny little feet as just perfection. Celebrating them, their essence, their humanity, unconditionally because they are. And treating myself with that same tenderness that I want my children to think about themselves for their whole lives. And seeing myself as a child really, really helps me too. And sometimes I’ll even hug myself and just breathe, and like you said, bring myself back to my body and just hug myself and say, “I love you. I love you.” And because, like you said, sometimes it is true that people are judging us because we’re all trained to do that. So if we can have our own back and really have that unconditional love that comes from ourselves and kind of lean into that and cultivate that more, at the end of the day that’s all we have, you know, from birth to death, hopefully, we have to be our own home.

LK: I love that. Yeah, I can talk about that experience. The broader narrative that we felt was so powerful in our book is this idea that we introduced, this metaphor of splitting from yourself when you’re young. Being split from yourself as an onlooker, and a subject and an object. You look at yourself. And that starts at a young age for most of us, especially little girls at seven or eight. It did for me. It hasn’t for my nine year-old yet, and I know that eventually it will. It hasn’t yet. She’s kind of been my guinea pig in this work, you know? And it’s been amazing to watch her. But to think about the fact that we all split from ourselves. We forget that we are whole. We forget how we used to live and breathe and be as little children. And then you see it in your own babies or babies you love, that are whole still. Oh, it’s the most powerful thing in the world to bring you back home. So our book ends with this metaphor of a reunion, of how you get back home to your whole self. And in the book, my favorite part of the whole book is the last chapter in writing about how you’ve been– we talk about it as the sea of objectification, the ocean that you’ve swam in as a part of yourself this whole time. And that as you practice your body image resilience to come back home, you see yourself on the shore. And not to give too much away, but the idea is that as you come closer and closer, you recognize your whole self again, your holistic sense of self that you had forgotten existed. The you that is whole, the you that is embodied, and you can embrace her again and promise her you won’t leave again for long. And that yeah, you’ll slip away sometimes, we all do, but you know how to get back.

And for me, one of those powerful experiences was around that idea of years ago, my husband taking pictures of me with my daughter when we were swimming, and then deleting those photos. And I remember being at home and just feeling, I think some of it is that postpartum emotions are stronger and heightened, and I remember feeling so ashamed of how I looked in those photos. And speaking aloud to like a divine feminine presence. For me, I see spiritual power as a lot of people who care about me that I don’t even know. It’s like a divine feminine being, and people who have passed on that I don’t know and maybe people who haven’t been born yet, and energy and goodness that is all working for me. And I also picture my own higher self, that Lexie that I have left behind on the beach that I’m trying to return to. And in that moment of feeling so much shame and pain, I was speaking aloud to that power and in that moment of just saying, “I feel so ashamed of how I looked and I feel ashamed for feeling that way about how I look,” then I felt this vision – I have goosebumps talking about it and I haven’t thought about this in a long time, so thank you for reminding me of this. But I remember I wrote it down in the notes on my phone immediately.

I felt this vision of me. I was looking at myself, not as myself, maybe as my higher self, maybe as a divine feminine being or somebody else that loved me holistically, and I saw me in that current body. I was doing something, I don’t know what I was doing, and I just felt overwhelming love for me, for Lexie, for my whole humanity in that body that I had just felt so disgusted by. And it’s the same way I feel about my babies. And it’s the same way that Lindsay and I want everybody to feel, regardless of their gender identity. We have done this work for so long as a side gig to our full-time careers because we desperately want people, especially girls and women who are up against so much, to know how powerful they are. To know that they are more, and to take on body image resilience in whatever way they can in the moment, to just come home. Because the world needs women, the world needs girls, the world needs the leadership, the voice, the power, the determination, the resilience of girls and women who can and will do so much for a world that needs it desperately and needs our voices desperately, more than ever. So, we do this work for them. And as I do this work, it heals me. It continuously heals me, and I’m so grateful that I was introduced to this my freshman year of college to be able to make a life out of trying to help people come home to themselves.

AA: Well, I can’t think of a better way to end the episode than on that powerful story and that powerful inspiration and challenge to everyone who’s watching and listening right now to come home to yourself. It’s overwhelming to imagine the healing and the joy that individuals can experience and then the collective good also that can be accomplished in the world once we free up, even if we just take out that negative cycle and the time that we spend there and all of the time and energy and money, honestly, and resources that would now be available to use for positive things in the world. It has all positive consequences, only benefits from doing this work. Again, I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart, Lexie. This was a beautiful conversation. I’ve benefited from your work more than I can say, and I continue to even just during this hour that we’ve talked. Thank you, thank you so much. And before we wrap up, can you remind everybody where we can find your work?

LK: Mm-hm. We have a strong social media presence despite not posting anymore. We took a backseat from posting, but it is an archive of our work and we stand by every bit of it. I reviewed our Instagram before this podcast to give me some of the talking points I love the most, and I stand by every bit of it.

AA: That’s fabulous.

LK: Our Instagram handle is @beauty_redefined. You can also just search Lexie Kite and Lindsay Kite and get there. Facebook is Beauty Redefined. And our website is morethanabody.org. We also have a non profit, Beauty Redefined, that is all linked through that morethanabody.org website. And our book, the culmination of our work that we very much stand by, has been out for four years, and you know what? Today it’s an Amazon bestseller, even four years later. So, people are still finding it and it has been really exciting and hopeful for us. It’s called More Than a Body: Your body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament. It’s available in audiobook, hardcover, paperback, it’s available in a bunch of different languages like Ukrainian and Russian and Korean and Chinese. So it’s out there.

AA: Wow! Fantastic. Wonderful. Well, thank you again so much, Lexie.

LK: Thank you!

We forget that we are whole.

We forget how we used to live and breathe and be as little children.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!