“I didn’t stop being a woman because I’m Black.”

Amy is joined by author and activist Mikki Kendall to discuss her book, Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot, and explore the lasting legacy of Jim Crow, the high expectations we place on women of color, and confront some of the ways in which white feminism has failed Black communities.

Our Guest

Mikki Kendall

Mikki Kendall is a writer, diversity consultant, and occasional feminist; she has appeared on the BBC, NPR, The Daily Show, PBS, Good Morning America, MSNBC, Al Jazeera, WBEZ, and Showtime, and discusses race, feminism, police violence, tech, and pop culture at institutions and universities across the country. She is the author of the New York Times-bestselling HOOD FEMINISM (recipient of the Chicago Review of Books Award and named a best book of the year by BBC, Bustle, and TIME). She is also the author of AMAZONS, ABOLITIONISTS, AND ACTIVISTS, a graphic novel illustrated by A. D’Amico. Her essays can be found at TIME, the New York Times, The Guardian, the Washington Post, Essence, Vogue, The Boston Globe, NBC, and a host of other sites.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: If I had to choose just a few sentences to represent the major theme of the podcast, I might choose the following passage from the book Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women that a Movement Left Behind by Mikki Kendall:

“There is no absence of feminism within Islam, the Black Church, or any other communities. The women inside those communities are doing the hard and necessary work. They don’t need white saviors and they don’t need to structure their feminism to look like anyone else’s. They just need to not have to constantly combat the white supremacist patriarchy from the outside while they work inside their communities. If mainstream white feminism wants something to do, wants to help, it is important to step back, to wait to be invited in. If no invitation is forthcoming, well, you can always challenge the white patriarchy.”

Powerful words from a powerfully thought-provoking book, again, Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot. And I’m so honored to welcome to the podcast the author of this book, Mikki Kendall. Hi Mikki, thanks for being here!

Mikki Kendall: Hi, thank you for having me on.

AA: I’m so excited to have this conversation. We’ll start out by having me read your professional bio and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourself a little more personally.

Mikki Kendall is a writer, speaker, and blogger whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Guardian, Time, Salon, Ebony, Essence, and elsewhere. She’s discussed race, feminism, violence in Chicago, tech, pop culture, and social media on NPR’s Tell Me More, Al Jazeera‘s The Listening Post, and BBC’s Women’s Hour, as well as at universities across the country.

She co-edited the Locus Awards nominated anthology, Hidden Youth, and is part of the Hugo Award nominated team of editors at Fireside Magazine. A veteran, she lives in Chicago with her family. In addition to being the author of Hood Feminism, she’s also the author of a graphic novel called Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists: A Graphic History of Women’s Fight for their Rights. And that I have to just throw in here, I know this book, Mikki, because a friend of mine and I developed a curriculum for a women’s history and gender studies class in California, and we used that book as part of our curriculum. It’s an awesome book, and I highly recommend both books to listeners. Again, I’m super excited to have you here. I wonder if you could start us off, now that we’ve established your professional bio, by telling us a little bit more about you, where you’re from, your family, and what has brought you to the work that you do today.

MK: So, I am a Black girl from the south side of Chicago. I am a regular-shmegular person 99% of the time. I just happen to have a lot of opinions and put them outside of my face. I was raised predominantly by my grandmother and some other relatives, and my grandmother would not have described herself as a feminist at all, but she also raised me to be one. So that’s always been this very funny thing to me because she was very much about, “you have to go to school, you have to have an education, you need to be able to take care of yourself financially,” and all of these things that would fit right in with mainstream feminism.

And she and I had a couple of relatively limited conversations about it when I was younger, because she would always talk about feminists as wasting their time. And I’d be like, “you vote, you want me to vote,” all of these things. And she says, “Yeah, I want you to do useful things, but I don’t want you to spend all your time arguing over whether or not bras are oppressive. Sometimes they’re just comfortable.” Because she lived through Jim Crow, oppression was very specifically for her around the ways that women, including white women, treated Black people, Brown people, right? And very specifically, she did not see herself in feminism, I think, because of white women. Because her experience– my grandmother was born in 1924, my grandfather was born in 1916. They lived through all of World War II and Jim Crow, the civil rights movement, all of that in a way that very much shaped her impression of things. And not that she was super, you know, “depend on a man,” blah, blah, blah. If you’re going to have a husband, don’t be dependent on your husband.

And I used to think how oddly complicated it must have been in her head to be raising this girl, and my grandmother kept trying to get me to wear skirts and sit nicely. And my tights were coming home with a hole in them, sometimes they were coming home more hole than tight, right? We had moments around pants, we had moments around what I was eating, how I was sitting, all of these things. And she would be trying to teach me to be ladylike but at the same time, it was absolutely unacceptable for me to be undereducated. I was a 15 year-old senior in high school and I had been off the track for a really long time, so there’s nothing less fun than being too young to drive at the end of high school. I was talking about getting a GED after I turned 16, because I was going to turn 16 in October of my senior year.

As an adult I recognize how dumb this plan sounds, but at the time I’m just going to take the GED test and be done with it. My grandmother had just had a radical mastectomy and I was telling her my plan and doing stuff for her. And I don’t know if anybody that’s listening has ever had surgery that massive, but this was back in the nineties. So they had taken the lymph nodes, a big section of breast tissue, and she really didn’t have reconstruction yet. She just had an open wound at this point. And I was talking to her about my plan and she grabbed me, and I want everyone who has never been grabbed by an old lady to understand that thing where you think they’re suddenly inexplicably strong. Yes, it’s not your imagination. All of a sudden, she could have beat Mike Tyson at this moment. And she explained to me that what I wasn’t going to do was drop out of school. What we did not do in this family was drop out of school, and that I was the result of generations of women who had fought hard to be able to be educated. Because her mother had been the first woman in our family who was legally able to read.

AA: Wow.

MK: So that’s where I come from. There is no stop, there is no quit. Because that was not available to them, it is not available to me.

AA: Wow. So it sounds like your grandmother was a really, really influential person in your life, toward your education. And then how did you start to develop your particular, I mean, I guess what you titled the book, Hood Feminism, and that intersectional sense of fighting against white supremacy but also patriarchy in there too?

MK: So, I had this very odd high school experience where I started off in the city in a majority diverse school. I moved in with my parents in high school, but they did decide to move to the suburbs. And in the suburb they ended up moving to there were 180 ethnic students, or 108, some number like that, in a school of 1800. So my world flipped. I’d always been in schools where either the people all looked like me or a significant number of them looked like me. And so even though at the time I probably wouldn’t have characterized it, it was my first real experience with the racism of the majority. I knew racism existed, but it was this sort of outside thing because I lived in a major city with lots of metropolitan people. And yes, there were neighborhoods that were problems. But by and large, I was in a place where you could get a job, go to school, all of these things without running into blatant, overt racism because there were consequences.

Moving to the suburbs changed that. And I came away from that experience, for lack of a better way of putting it, understanding better why she would not have described herself as a feminist. Because it was my first time running against teachers who did not care about me. It was my first time having classmates who could be racist and there would be no consequences to speak of. I had this fight, for lack of a better word, with a white girl who had been picking on me, all of that. And I guess in suburban lexicon we were supposed to be in some hierarchy, and I did not speak white suburban girl. I still don’t really understand all of that hierarchy. So when she started trying to bully me, I responded like a girl from the city, right? If you put your hands on me, I put my hands back on you. We ended up in the dean’s office.

And again, I was much younger, I was 15 about to turn 16. This was the era of you holding your kids back a year so they do better in school, so she was 19. So, we’re in the office and this was a school that was definitely punishing Black kids much more stringently than they did white children. And they’re doing the thing, and my guidance counselor had come in during this whole thing because they were going to expel me or attempt to expel me. And my guidance counselor was like, “She’s a minor.” And the first time she said it, they just kept talking and she was like, “She’s a minor. You can take that 19 year-old and that 15 year-old and try it, but then somebody’s getting charged and it’s not going to be the minor.” And so that was also sort of my first lesson on how this racial dynamic could break down, because she wasn’t concerned until someone said I was a minor. I wish I could describe how smug and certain she was that I was going to be the one in trouble despite her starting the fight.

And so I go through that, I join the military, I have my life, right? And that’s a weird little defining moment. There’s a bunch of other little defining moments where I’m sort of confronted with the ways white supremacy works, but I’m also confronted with the fact that the white women under white supremacy, including the ones who are sort of toeing the line, aren’t actually getting anything from it, right? The army is a great place to learn that regardless of the whole “equality in the uniform” whatever, gender plays a huge role. The US military has an almost 100% sexual harassment rate and an extraordinarily high sexual assault rate. And not that the Black girls were safer, per se, but we at least had a chance of associating with each other to look out for each other. White women were not necessarily doing the same level of being buddies and moving in groups, and they were thus bigger targets because they were alone more often. That community structure that I was used to, that other girls of color were used to, doesn’t necessarily extend itself. And so this does inform some things.

it was my first time running against teachers who did not care about me. It was my first time having classmates who could be racist and there would be no consequences to speak of

By the time I get on the internet and I’m an adult, I’ve gone through college and I’ve finally been exposed to reading all of these books about feminism, but I’m noticing in my classes and everything that they talk about girls like me, they don’t actually talk to girls like me. They don’t actually engage in any meaningful dialogue about our lives. Not that this is a criticism, but I was bothered by the fact that I had bell hooks and Alice Walker and This Bridge Called My Back, and then the field started to run dry. Even online, except for my compatriots, other Black women, I was still seeing people talk about lipstick colors and last names as though these were the most important issues. And I couldn’t understand how we were still having these conversations when the Voting Rights Act was already under attack, the Anita Hill case had come and gone. We were already seeing the consequences of ignoring misogyny, the consequences of ignoring bigotry. And so that really got me started talking about it and then thinking about it online.

Hilariously, I didn’t think I was going to write books about it at that point. I was just trying to figure my own stuff out, and I write to figure my stuff out. But then I’m in these conversations where, for lack of a better way of putting it, I start to realize that some of us have a specific set of knowledge about how the world works below a certain income level. And I could talk to lower-income white women about poverty and class and all of these things, they weren’t necessarily great about race and they weren’t necessarily bad about race. But there came a point when you were talking to middle-class and above feminists who, especially those who would say, “Oh, my parents paid my rent, my parents paid my bills.” And whatever they would want to be able to be the ones writing policy about, things like food stamps or schools, they had no experience and they were considered experts. And I’m like, “Well, if that’s the case, anyone can be an expert.” So I started talking about what I want to talk about. I did not expect it to turn into this book. But I have to say, all of my life experiences up to that point had led me to a place where I could see the value of community. I didn’t necessarily see the value of hyper-individualistic feminism, because not only was it not paying off for women of color, it genuinely doesn’t pay off for most white women. The CEOs, maybe it’s paying off for them. Everyone below that is not necessarily getting anything great.

AA: Wow, that’s fascinating. Well, that leads into the first question that I wanted to ask you to set the scene for the rest of the discussion. You write, and I’ll quote this one sentence, “For a movement that is meant to represent all women, it often centers on those who already have most of their needs met.” That the feminist movement, as you describe it, mainstream white feminism centers on people who already have most of their needs met. And the way I understood it is that the thesis of this book is that if we care about all women, all women, then there are a host of other issues that we need to be tackling first. Can we talk about that as we start the conversation?

MK: Like I was saying about my experience in these conversations, I was in conversations, I mean, looking at a kind of feminism that doesn’t prioritize hunger, or housing, police brutality– We had that women’s march with the pink hats and they were posing with the police officers like the police were going to be on their side. And maybe the police are on their side, but for how long are the police on your side? And I was looking at these issues and going, I know that we’re experiencing all of the consequences of poverty, so are white women, so are nonbinary people. Why are we talking as though the choices are CEO or non-existence? There’s all of this other stuff going on. And when I started to talk about race and how it impacts things, there was a whole thing about “you’re being divisive.” And I was like, so again, if we’re a movement for all women, and you don’t experience racism, it doesn’t mean talking about racism is divisive, it just means this conversation isn’t about you. And I really wanted feminism to sort of grow the F up. Put on your big girl panties and realize that sometimes you have to do work that does not apply directly to you. Sometimes you have to put in the effort because we’re seeing the consequences of not putting in the effort.

When COVID hits all of the people who said SNAP didn’t matter, or protecting workers’ rights at the state and federal level didn’t matter, it really sucks to want to apply for unemployment or food stamps and there not to be any workers there because they’ve been getting laid off and not replaced. It really sucks to find out that those politicians you voted for because they lowered your property taxes, lowered property taxes by cutting funding for the programs you now need. And so when you start to get into this place with feminism, the idea that we’re all in this together… we’re all in what together?

Just empowering women isn’t enough. What are we empowering them to do? Who are we empowering? What are we empowering them to do? How are we going to use that power? Because if we’re not asking those questions, we end up with Marjorie Taylor Greene. Feminism, as hard as this is going to be for some people to hear, feminism helped put her there. Feminism gave her, over to a whole host of others, access to power with no critical analysis of how they were going to use that power. And we saw this with Megyn Kelly. We’re going to see this more and more. This idea that we’re all women together, but 47% or 53% of our elections are voting for some women not to have rights, are voting for some women not to have safety, for some women not to have protections. And the bell that is ringing in Texas, in Florida, in all of these states, Georgia too, for that matter, is one where suddenly white women are being impacted by the decisions of feminism even though it’s an indirect decision.

I know someone’s going to tell me, “No feminists voted for–”. Statistically speaking, I bet that some of the people who identify themselves as feminists also voted for these politicians. The math does not lend itself to no one who thinks of herself as a feminist. Whether we love this idea or not, Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert and all of the other people that we’re talking about here, not only do they benefit from feminism, they very clearly will tell you that as far as they’re concerned, they’re feminists. And we can no true Scotsman fallacy that, but the reality is that we have to talk about what women are being empowered to do, what white women are being empowered to do. Because when we got to the point of suffrage, part of the goal of white suffragettes, and yes, not all of them, blah, blah, blah, was to uphold white supremacy. This is not a decision made after the fact. They said this in their speeches, that white women getting the vote would preserve white supremacy. Well, we’re here now, and now we have to have a different conversation for the next hundred years because the 1920s wasn’t a great decade. I didn’t really want to go back to it, but we seem to be repeating a lot of our old mistakes. I don’t want us to keep going.

AA: Yeah, thank you. One quote that really gutted me when I read it, I think it’s Rachel Cargale who said that feminism is white supremacy in heels. And that was really hard to read and has stuck in my head forever after reading that. And then after researching the history on this podcast, I discovered everything that you just talked about, that it really has been and continues to be. One other issue that you bring up right in the beginning is, you say, “Feminism as defined by the priorities of white women hinged on the availability of cheap labor in the home from women of color.” And that’s come up on our podcast several times, but I’d love to talk about that more. And that’s something that I grapple with, in asking myself, how can I make sure that in all of my actions, I’m never exploiting other women in the name of, you know, girlbossing? Can you talk about that, Mikki?

MK: So the thing with girlbossing, I get the draw of this term. But I keep coming back to the Yahoo CEO who put a daycare in her office for her child. A single space for her child to come to work with her and then remove work from home for all of her employees. And we get so focused on the boss part, the power part, the reach, the money, we ignore what that means to the people under us. There’s no duty of care being included in the girlboss rhetoric. You’re not supposed to make sure your employees are happy or healthy, you’re supposed to make sure you’re in charge. You’re supposed to be a girl in charge is the limit of that.

And so a lot of times when we’re talking about what privileged people could be doing, it could be as simple as paying a fair and living wage based off of real numbers, not off some arbitrary statistics from 10-20 years ago or what you’re comfortable with. I see people say businesses can’t afford to pay $20-30 an hour. If you’re not making nine figures as a CEO, I promise your business could afford to pay your staff a living wage and you still take home plenty of money. You could still take home high six figures and your staff would immediately make way more money if you’re in these big, successful businesses. You could even take home seven figures, as we see some CEOs do. But instead, we’re seeing right now in Hollywood, we’re seeing a $27 million a year paycheck. But you don’t want to pay people enough for them at $26,000 a year to afford their health insurance. That is an insane schism.

And we’re seeing this with the girlboss right now. People who want to make clothes or whatever, and they’re fine with the sweatshop production. Well, then you’re not doing a feminist thing here. You’re just doing the same repressive thing and calling it feminism. And so I think a lot of it is as simple as asking yourself, what do I have? What is enough? What is more than enough? And then capping this number somewhere in your brain, well south of “Ooh, I can hoard more money!” If you’re going to girlboss, I’m not recommending girlbossing, but if you’re going to girlboss, pay your employees enough to be able to pay their bills and eat. And you’d be amazed how many of your employees will stick around. If you’re going to girlboss, use that power for something good. If you want to throw your money around, buy a politician and make him or her support reproductive freedom, make him or her support rights to free and public education, make him or her support the right to vote for everyone. Because instead buying a politician so your business can do more business however dirtily, or you can get away with not paying taxes, you’re doing something, but I wouldn’t call it feminism.

AA: Mm-hmm. We talked in the first season of the podcast, we did an episode with a woman who’s a dear, dear friend of our family, but we met her because after I had my third baby she started cleaning our house. And she became, again, a very, very close friend. And I was shocked and devastated to learn years after she had been in our home, she knows and loves my children, I know and love her children, we would chat every time she came over. But she had been experiencing domestic abuse, she was undocumented, she had all of these private struggles that she had never shared with me in years of me thinking that I knew her really well. And I hadn’t recognized the privilege and the hierarchy that she felt, like when I would say, “How are you?” She’d be like, “Oh, great!” And not feel comfortable telling me what was really going on in her life. And that’s something that I would say to listeners too, the people who are in your home, in your yard, that we interact with as human beings, ask them real questions. And I mean, once I knew that some of these things were going on, we could help. And as friends, as people who genuinely loved each other. And it was really striking to me, and I’ll never forget how awful it felt to realize that she had been carrying these burdens without feeling like she could tell me about them for so long. And I guess I just hadn’t asked the right question. So that’s something I’ll throw out there too, is to ask the human beings in your life about their real lives, and then find opportunities to lift other people up too.

Okay, one term that I had never seen quite like this before was you talk about, we’re shifting gears here, Mikki, and I’ll ask you about this term that I’ve never seen written quite like this. You talk about the Strong Black Woman with a little trademark sign after it. Can you tell us about the Strong Black Woman™?

MK: So one of the things that comes up a lot is this expectation that Black women will be able to take care of anything, right? Black women are strong, Black women are sexy, Black women are wild, but Black women are strong is always the first part of that. And it means that Black women are not allowed to be weak, to be sad, to have a mental health crisis, to grieve in public without people dissecting whether or not their grief is real. Because Strong Black Women really traces back, to be honest, to slavery and after this idea that you could have your children taken from you every year and sold away, never to be seen again, and then you were expected to go back to work. And that was chattel slavery in America. And then in Jim Crow, we run into this thing where Black women who wanted to stay home with their children were accused of being sluggards and lazy and they would be arrested or they would be assaulted. And if they were physically assaulted, sexually assaulted, her husband might get lynched. Or she could get lynched. And so this dehumanization project is older than people sort of realize. And now we’re at a point, technically Jim Crow is over, slavery technically over, not really because the 13th amendment is still worded the way that it’s worded.

And when you get to this place, you say, “Well, why can’t you take care of me?” And people don’t even realize what they’ve picked up and that this might as well be a trademark emblem hovering above their heads. Because their expectations are that the Black women can take whatever comes their way. And even if they complain about it, they cry about it, you don’t take that seriously. They’re Black women, they’ll figure it out. And it unfortunately impacts Black women inside their community via misogynoir and other things, and outside their community via misogynoir and other things. What happens is, and we’re seeing this now with the Carlee Russell case, I have no idea what happened to this woman but I am watching people go from sympathy because she went missing and then she reappeared, to a very aggressive “Why isn’t she telling us everything? Why?” What we know is that if she’s a victim of a crime or an assault, trauma will make you silent. Fear, the investigator, who knows? But people don’t really perceive her to be human in any meaningful way. People often, when we’re talking about Black women, whether they realize it or not, that whole “Black women will save us” speech that comes up every time election cycles go bad, I’m not really sure what white women think they’re going to be able to do. There are more of you than there are of us. We can’t outvote you.

AA: Yikes. Yeah, there was a passage where you spoke about this on page 73. Would you mind reading that?

MK: No problem. “Why have Black women had to be strong? The toxic elements of Black and Brown cultures of hypermasculinity are born in part out of the impact of low wages, where the option of a woman not needing to supplement the household income was never on the table. This is a culture where women were largely in charge, not because they had fought to be, but because the men in their lives and communities were being imprisoned or killed with little rhyme or reason. Mass incarceration has damaged so many communities, removing many of the more traditional social customs around family from the realm of possibility.”

AA: You write about the notion that Black women are stronger and so they have less need of support, right? And then maybe we’ll get into the ways that we can support Black women more as we go in the conversation. Was there anything that you wanted to talk about that that quote brought up?

MK: Well, I think one of the things I wanted to talk about is that because of these obstacles, we’re now seeing a trend where people are saying that Black women are so masculine. And I can’t think of anything more bizarre to gender than being able to pay your bills and stay alive in the hyper-capitalist empire. Black women aren’t soft enough, they insist on having degrees and working. I don’t know if you’ve seen outside, but the way the bills are set up, everybody’s working. Very few people at this point can afford a life where they’re not ever going to work. And all of the people who can are largely born wealthy. The rest of us go to work. It’s not gender, it’s survival.

AA: The next topic that I wanted to talk about is the concept of #solidarityisforwhitewomen. And I would say that one of the quotes that stood out most to me from the whole book, Mikki, was where you say “Sisterhood is a mutual relationship between equals.” And so you call out a bunch of different situations where white women will invoke the cause of sisterhood and solidarity, and you have some critiques of this approach. Can you talk about that?

MK: I remember Ms. Patty Arquette’s speech where she was asking where everyone was to support white women and actors and whatever.

AA: Could you actually, if you would describe that, I had never heard of that. So if you could describe that whole thing, I think that would be really valuable for listeners to hear about.

MK: Sure. So, Patty Arquette gives the speech, I believe it was the Oscars, where she starts to, for lack of a better way of explaining it, to every woman who gave birth, every taxpayer, all of these things. She starts off talking about how we have fought for everybody else’s equal rights, it’s time to have wage equality in America. People were excited, people were clapping, and then she started asking marginalized people, where were they? Why weren’t they showing up? And it was the oddest turn in a speech. It’s the lines that the law enforcement tried to write. It’s time for all the women in America and all the men that love women and all the gay people and all the people of color that we’ve all fought for to fight for us now. I didn’t stop being a woman because I’m Black. Let’s start there.

On top of that, where were white women showing up for other people like this? ‘Cause I need them to roll the footage for me because I’ve never seen it. And this is one of the things about those calls for solidarity, for sisterhood; you got to show up for people before you start demanding they show up for you. So you’d have to show up at pesky things like school board meetings, sure, but also at those Black Lives Matter protests. Also at those protests around immigration. Also when it isn’t just the rights of white women and abortion that are on the table, you have to show up for those protests around disability, you have to show up for all those things. And not just at the protests, you have to show up at the voting booth. You have to show up with the politicians you elect when they don’t do what they’re supposed to. Or if you’re running for politics, you need to be putting on the table that you’re going to actually do what the people who elected you do, which is take care of people, not just pad your pockets.

And that sisterhood line drives me nuts because yes, sisters fight, but also some sisters don’t speak to each other. Some sisters are permanently and totally estranged. And part of why they are estranged is that one or more behaves badly. And you cannot, in good conscience, I know people will disagree with me, say “Black women, save us from ourselves, but also Black women save yourselves. Indigenous women save us from ourselves, but also save yourselves.” Nope. First of all, you’ve got to save yourself. The rest of us are not land troops to protect you. You’re going to have to show up at the vote. You’re going to have to argue with Uncle Barry, you’re going to have to do all of those hard things that you don’t want to do. It’s going to be messy at Thanksgiving and Christmas and all of that. Because if you don’t, if you’re not challenging Aunt Susan on how Aunt Susan thinks or votes, then you’re not showing up for the people Aunt Susan’s vote impacts. And sure, you may not be able to change her mind, but you will certainly get a lot further with her than some other person will, even if it’s awkward, even if it’s uncomfortable. Because the theme of #solidarityisforwhitewomen is that even in that original conversation, the idea seemed to be that white women were protecting each other, and everybody else that was targeted by that man whose name I generally don’t say was supposed to figure that out. If that’s the case, if that’s the situation we’re in, when we look out for us and you look out for you, don’t ring the bell for sisterhood.

You’ve got to save yourself. The rest of us are not land troops to protect you.

AA: Speaking of blind spots for white women and complete tone deafness, because I was stunned by that Patricia Arquette story and quote in the book. I’d never heard it. And I couldn’t believe it. But another story from the book was about Lena Dunham. And this is where I was kind of thinking, how would we define mainstream white feminism when you refer to that? And so it was really helpful to have some of these examples that were in the press. And could you talk about that situation with Lena Dunham and Odell Beckham Jr., because that was also a really great illustration of the kind of mainstream white feminism that you critique in the book.

MK: So, one of the things that was a big news story about nothing. Odell Beckham goes to, I believe it was the Met Gala, and he’s at a table with Lena Dunham and Amy Schumer. He was on his phone, I have no idea what he was doing, no one knows. They extrapolated from that that he was ignoring them based on their size. It’s an entire bit about how he didn’t whatever, I don’t know where we were going with this bit. We make this bit public. We’re tweeting about it, talking about it, trying to get, according to them, a laugh. Although Odell Beckham had never said a word, negative nor positive. He just hadn’t been friendly to strangers. And who knows what was going on that day. I don’t know if he got news about his contract or his mama or whatever, but he was on his phone dealing with his life. And they decided that the world revolved around them to such an extent that he wasn’t even allowed to not pay attention to them, though they were complete strangers who, as far as anyone could tell, also never attempted to speak to him. They never struck up a conversation. For all I know, even as I’m saying, he could have whatever going on, he could just be shot. And it sort of frames Odell Beckham as this horrible guy who doesn’t like fat women and all of these things.

I thought, this is how false accusations used to start. Nothing has occurred. And not to say that what Odell Beckham went through is at all comparable to what Emmett Till went through, but every once in a while, someone brings up the fact that Carolyn Bryant didn’t tell the truth and someone died because she was a liar. Emmett Till was murdered because of a stupid lie. Odell Beckham had whatever public career damage done because of a stupid loss. And then we see this because then when Aurora Perrineau comes forward and she’s talking about being sexually assaulted by someone who’s supposed to be a friend of Lena Dunham, who has made what was supposed to be the show of the century or the millennia for young white women suddenly swings out in defense of this friend and had to be visibly, publicly reminded that just because he was nice to you has nothing to do with how he treats other people. It has nothing to do with her experience. And especially when you start to consider that statistically speaking, most people who commit acts of sexual violence have friends, they have family, they have loved ones. There are people who are safe from them, whether that is because those people are not their type or those people don’t look like them. Who knows? You cannot say what they would do, you just have to fall back and let them deal with their world and their behavior with the person they engage in that behavior towards.

AA: Okay, the next topic I wanted to ask you about is the hypersexualization of Black girls and women. You mentioned the staggering statistic that 40-60% of Black girls are sexually abused before age 18 and then they’re often victim-blamed by being called “fast-tailed girls.” Can you talk about that a little?

MK: One of the things that happens, and this goes back to the Strong Black Woman thing, is that when Black girls are very young, we’re gonna go with, let’s say, as young as five. It’s actually sooner than that, according to some data, they are somehow perceived as being little adults and they are held to higher standards. They are given less protection. This is a problem, again, inside the community and outside the community. And it’s not a universal problem. But what tends to end up happening is that they are then labeled as being fast, just for developing. And it sets up a horrible dichotomy where if you are a predator, you already have the perfect target that no one will believe or care about, or even if people do, no one in authority will do anything to you unless they’re forced to. And so we hypersexualize Black girls by deciding that their body’s simply developing. “Oh, look at her butt. She’s so sexy.” And we do this in general to little girls, and then we turn it up a notch for Black girls, because somehow their skin color makes it okay to say even worse things.

And every Black girl I know has stories from, you know, nine or ten grown adults saying absolutely atrocious things to them. And then you run into this thing where, when they complain, when they say anything, the first thing they’re told is, “Well, you were being fast. What did you have on when you were out here fanning yourself around,” or whatever. And it’s a throwback to things that happened during Jim Crow, because in America for a long time, it was legally impossible to rape a Black woman. The roots of the civil rights movement are in the Recy Taylor case where Rosa Parks attempts to get justice for Recy Taylor, a married woman assaulted on the side of the road, and then the men who assaulted her basically say, “We thought she was a prostitute. We thought she was selling it.” Or some version of that in a couple of different stories. But really all they were ever facing in terms of consequences was that they would have to pay a fine. There was nothing else, because legally they could do whatever they wanted to her still. She didn’t have any status.

And though we don’t think that we still do this, in some ways we still do this because we already question every rape victim. If you sexually assault someone, it’s very unlikely you will go to jail in general. If you sexually assault a Black woman, you are almost a hundred percent going to get away with it. And it’s not just sexual assault, it is domestic violence, it is in my city, in Chicago, it is serial killing. Black women were being found murdered and set on fire in alleys. And in any other situation, if those were young white women all being found murdered and dumped in similar ways, there would have been an FBI task force and all of these things in place after the second or third victim. It was more than 50. And the city still continued to say, despite a different serial killer being caught in Indiana who admitted to having hunted in Chicago, the city still continued to say we were being irresponsible for asking if it was a serial killer. Their answer was that they were in drugs and prostitution. That doesn’t mean they weren’t targets of a serial killer. A former FBI profiler says this is a serial killer. He believes there’s, I think, three operating in Chicago at any given moment. And as you’re getting into that data, and then you start to look at the hypersexualization of Black girls and the idea that they’re fast, they can’t be assaulted, that they bring it on themselves.

And we saw this with the R. Kelly case, where people kept insisting that girls age 14, 15, 16 knew what they were getting into. That man was in his fifties. I have a story, I have a niece who has a story, and there are more than 20 years between us. I have talked to women my age and younger, up until he went to jail, who all have stories. And the thing they have in common that allowed him to be a predator for the last 40 years almost, was that his victims were primarily Black. Not all of them, but the vast majority. And that is a Black man preying on Black women and nobody really cared except for Black women for a while.

We saw this with the Daniel Holzkopf case in Oklahoma, a police officer guilty of sexual assault. Until the internet really got on the neck of the criminal justice system down there, it sure looked like he was going to get away with it but he didn’t, he got sentenced to more than 200 years. But part of why he gets sentenced to all of that time was because on his pants was DNA from one of the people. When they picked him up, he had her DNA on his pants. He still didn’t plead, he still insisted it was a lie even though he couldn’t explain the DNA. So when you think about that and you think about how comfortable he felt because he had more than 18 victims, I don’t believe he got convictions in all of those cases, but there were many, many victims. You start to say, at what point are Black girls safe? We saw this in Vegas with the boy who lured a Black girl into the bathroom and raped and killed her. Initially, the press talked like he had just had a temporary break from reality. It took a lot for him to face any consequences because, well, why did she go in the bathroom with him? We think of Black girls as being disposable.

AA: It’s heartbreaking and infuriating. Okay, let’s talk about the next topic, and this is something that’s been on my mind a lot lately for the past few years. I wrote my master’s thesis on this topic, and that is white women trying to teach women of color about sexism. And you write a really wonderful passage here that maybe I could have you read, Mikki. Is that okay?

MK: Sure. “For many marginalized women, the men in our communities are partners in our struggles against racism, even if some of them are a source of problems with sexism and misogyny. We cannot and will not abandon our sons, brothers, fathers, husbands, or friends, because for us, they don’t represent an enemy. We have our issues with the patriarchy, but then so do they, as the most powerful faces of it aren’t men of color.”

And one of the things about this, I’m not ever going to tell you that communities of color don’t have sexism. We very obviously do have issues with sexism and gender roles, but we also have issues with racism. And I sometimes, especially when I see white feminists trying to say those men– Hollaback had this thing where they were talking about men on the street harassing them. But then the video they showed is a white woman walking through a neighborhood and simply Black and Brown men speaking to her. They weren’t even catcalling her. And then it comes out that there’s another video in which a man is catcalling her, and it is a white man in a fancy convertible. But you chose to run your story, your video frame this way, and got a lot of backlash for it.

And one of the things that’s always wild to me, because I don’t know if white women realize that we can see the things they post on TikTok or YouTube. We can see the interactions they have with their spouses in stores, in public, and the policing of our handling of sexism. I need you to turn around and look at what you’re inside the house with. Because I see white women making videos, especially right now, during the pandemic talking about how difficult it was, we’re both home working but I’m the only one taking care of our child. I had to close my business because my husband couldn’t handle our toddler three days a week. All of these things. These were white women married to white men who were fully and clearly sabotaging their careers, fully and clearly sabotaging the family’s finances because they didn’t want to have to change a dirty diaper or occupy their own child.

One of the things that made that such a bizarre thing to watch is that statistically, black men are more involved parents than white men. And the stats are there, I suspect in part because at least judging off the stories that made it to the New York Times and all of that during this, I saw white men in egalitarian feminist homes, in theory, where they wouldn’t even put the kids to bed. There’s a woman who made a video today talking about how when she was in labor, her water had broken, her husband came to ask her what was for dinner.

AA: What?

MK: He brought her the dog bowl when she was nauseous. I was very confused at every step of this. And she tells it like it’s funny and it’s a joke and whatever, but I think if you’re going to talk about sexism, you need to talk to each other. You need to leave us out of it, because some of the things that we’re seeing, again, not to say that women of color don’t have problems, but you have your own knitting to tend to. And I think that that bit of “I’m going to teach you about sexism because your culture normalizes certain things that are not a part of my culture,” fixing a plate is a big thing in Black American culture, and it’s literally just supposed to be a mark of respect to the person who has gone out and worked hard all day. I’m not going to say that it’s always the most comfortable thing within anyone’s family dynamic, everybody’s stuff is different. But sometimes the only place Black men were experiencing respect was in their home, nowhere outside. Sometimes the only place Black women are experiencing respect is in their home, because the other side of this is that the person most likely to open her doors and speak kindly and gently to her and all of these things was that man she was married to.

Now, it doesn’t always work out, but that’s the framework of a lot of these things that we will see from the outside. We will see Indigenous women braiding the hair of their children and their spouses, and it indicates certain things within their culture. We’ll see the same thing with Latinx and Black cultures. And so then when white women say, “But sexism! Why are you the one taking care of his hair?” Babe, I don’t have to worry that he won’t bathe the kid or feed the kid. We have problems, but our problems are not the same. If I am in labor, I don’t have to do all of the things that you are apparently expected to do. And I know that it’s going to be chalked up to your husband being a lone animal, except I’ve seen about 7 million versions of this. Even though studies that say that women pick up seven hours more work with marriage, I always want to ask, and this is my least helpful feminist moment, how are you picking up that much more work? How are you married to somebody who won’t start dinner? How are you not throwing things at his head? And then I have to remind myself that that is not a helpful thing to say.

AA: It might be. Yeah, that passage in that part of the book was really memorable for me. And that’s kind of why I chose that concept to start the episode with, the concept of how arrogant it is to make assumptions when we see things. Like you mentioned this plate of food, that was really moving for me to have that visual of a Black couple and a woman giving her husband a plate of food as a mark of love and respect. And when you did write that that might be the only place, in his home, that that Black man gets affection and respect. And so just the audacity, how wrongheaded it would be for a white woman to wag her finger and say, “Look at this housewife who’s serving her husband, that’s so sexist.” That was really, really thought provoking and I’m really grateful for that, Mikki.

As our last topic, I’d like to dive in a little bit to some of the issues that we brought up at the beginning of the episode and talk about some of the really critical issues that white feminists too often ignore. You list food insecurity, access to quality education, safe neighborhoods, a living wage, and medical care. Maybe you could choose a couple of those that you’d like to talk about.

MK: So, I want to talk about food insecurity because inflation is happening right now real bad, and I’m seeing people really struggle. Especially since, once again, food stamp budgets have been cut. And one of the things I would love to see mainstream feminism speaking up about more often is the role of hunger. And I know that we have activists who tackle hunger and food insecurity, but I’m not seeing that foot on the proverbial neck of politicians to make sure that women are able to eat, women are able to feed their kids, that our feminist community, whether you are nonbinary or trans, and trans women are women, but whether you’re trans-masculine, trans-femme, are able to just afford basics. Because there’s always this call of: Why aren’t more people showing up for protest marches? Why aren’t more people writing emails to combat the attacks on reproductive rights? Why aren’t they showing up? People tend to show up when they have a full belly. People tend to show up for literally everything else when they have their basic needs met. And it’s very easy to sort of blanketly go, “Well, capitalism and jobs.”

And that’s true. I’m not telling you that capitalism isn’t a major part of this, but I also recognize that many of the people who have access to power, who have access to push for other things, don’t ever mention poverty and hunger and being unhoused as baseline needs to be met. And that when certain groups do, leftists will bring it up, some of them, Black feminists will bring it up, Brown feminists will bring it up. But when we do bring it up, it’s like, “Oh, those aren’t feminist issues.” How are they not feminist issues? Do you eat? Do you need housing? Would you like your kids to be able to go to a decent school? Would you like your kids to have a school to go to with books in it? Because all of these issues really tie together. When we start talking about housing insecurity and poverty and all of these things, the fundamental basis of anything is that once your needs are met, you can pursue your wants. You can pursue higher goals, whether that is education or better healthcare or whatever. At base, if people are starving, they have to focus on surviving. And if they’re so focused on surviving, they can’t do anything to thrive. They don’t have time.

AA: Are there any more that you wanted to dig deeper into, Mikki, or should we wrap it up there?

MK: I just want to talk briefly about gun violence–

AA: Oh, good.

At base, if people are starving, they have to focus on surviving. And if they’re so focused on surviving, they can’t do anything to thrive. They don’t have time.

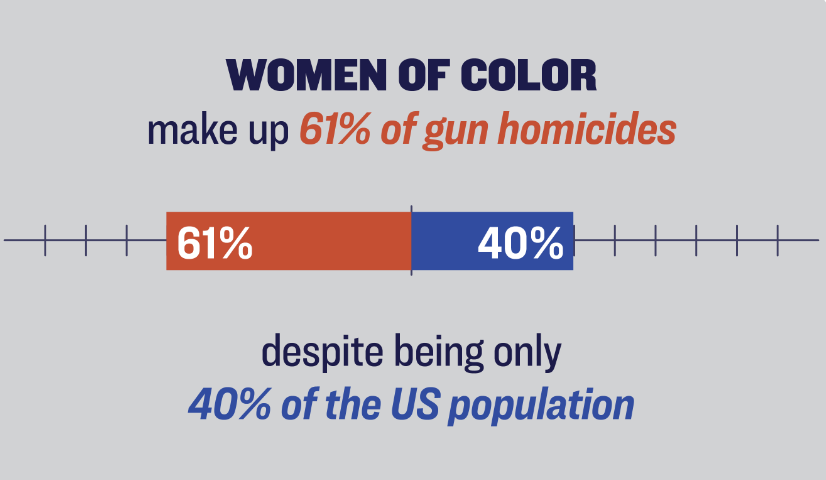

MK: Because the US is hurtling itself further down a slope. I don’t even think it’s a slope at this point, it’s just a well. We just jumped over the edge and are plummeting toward the bottom, statistically. There is a narrative that gun violence is happening in cities. That there is the most dangerous city, those lists that come out, and invariably, my city, Chicago, is always the one people expect to be on the list, and it’s never the one that’s actually on the list. And the thing about gun violence in an American context, and it’s not just in America but we are by far ahead of the pack, is that the same people who want to stop books from being in schools, who want to stop women from having the right to choose, are perfectly happy to hand anyone who wants a gun as many weapons as they can with no limits. And then they will say what has to be the stupidest sentence I’ve ever heard in my life when 10, 20, 30, 400 people are shot: “My thoughts and prayers go out to the victim.”

I want people to imagine a world where politicians spend less time trying to tell you what basic needs you can’t have met and more time actually tackling problems. Because again, we’re back to, and I’m holding my face towards the NRA’s adherence, not just the NRA proper, we’re back to this idea that because we can, we should. Yes, legally, we can own guns. I say this as someone who also has guns. Mine live in a safe, and they go to the range. Mine don’t go with me to the grocery store on the average day. Mine don’t go with me to the movie theater. One of the things, though, that’s always been so frustrating to me is that people will say, “We need those because the government–” The government is killing you in 800 other ways. The guns are not going to be the thing that saves you. We’ve had, I think, three different plant explosions, God knows how many storm events, climate change is occurring. You can’t shoot it. You can’t shoot a hurricane and make it stop, so let’s move on. You can’t shoot a virus and make it stop.

And I think that this is the thing that is very hard for people to really reckon with is that not only do I think feminism should be showing up, but the patriarchy is benefiting and also harming itself in this weird circular logic, where the fear of gun violence keeps women in abusive relationships. It keeps people from doing certain things, keeps girls out of school, all of these things, but also it bolsters the patriarchy because then someone’s got to protect you. Who’s protecting you and what are they protecting you from? Because I often see men who say, “I need a gun to protect my family.” The most dangerous person in the house to your family is you with a gun. The most dangerous person to men is other men with a gun. At some point, when we’re talking about gun violence and race and class and all of these things, we have to have a genuine conversation about why America loves guns. And America loves guns not because of hunting or any of the other stuff. I mean, yes, they’re fun to shoot, I’m not going to lie to you. But because America wants the option to do harm to other people, and then it’s woven so deeply in our culture that we don’t reckon with that.

But we want a lethal solution to a non-fatal problem. And we’re seeing it happen over and over. “I was mad at this girl who wouldn’t go on a date with me so I shot up my school.” “I’m mad my wife left me so I killed our kids and her,” or tried to. We are not just seeing gun violence happen like a storm. It’s not the rain. The story behind the mass shooters, the story behind domestic violence, it’s almost always someone who hates women, who has a history of violence against women. And we live in a culture that would give that person a gun because we live in a culture that doesn’t really value women. And so this goes back to my whole thing with mainstream white feminism. That same culture will let you be killed in your suburban home by your husband, your brother, your uncle, and he will maybe face consequences, but the system will make it possible for someone just like him to get a gun the same day. In some states, they will make it possible for the gun that was used to kill you to go back on the market to be resold. Because they don’t destroy them, they just resell them.

Gun violence is an everyone issue. It is a feminist issue, it is a poverty issue, it is a race issue. It is an everyone issue. And if we don’t tackle it, there won’t be anything else left to save. My only other last takeaway is that for everyone that is listening to this, that is thinking, “Okay, so these are problems, but they’re not my problem.” You don’t know when they’re going to be your problem. You don’t know what your future holds. And you should be planning, we’re going to call this insurance, for a safe and functional society, no matter what is happening in your life. If you don’t need a social safety net, great, but you should want a social safety net to be there for you, for people like you, and for people who are nothing like you. Because if we are not taking care of each other, then what are we doing here?

AA: Thank you so much. I couldn’t agree more. I’m so grateful for your book, Mikki, so grateful for the message that feminism, I mean, feminism the way I see it, means looking out for all women and also all of humanity. And the end goal is that everyone can thrive on this planet together. That should be what we’re all focusing on and working toward. So for anyone who’s listening, I highly recommend buying this book, Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women that a Movement Forgot by Mikki Kendall. And again, Mikki, I want to thank you for being here today. I learned so much from you and it was a real honor to have you today. Thanks so much.

MK: Thank you for having me!

AA: And that wraps up today’s episode. Before I go, I want to thank Sam Rose Preminger for editing and production and Aubrey Eyre for our social media. And as always, I want to thank you listeners for being here. Make sure to check out our YouTube channel, @breakingdownpatriarchy, which features short, super entertaining videos that were created specifically to be able to share with friends and family members. Huge thanks to Ralph Blair and Aubrey Eyre for their genius work on that series. And if you want to show your appreciation for this excellent ad-free content, the most helpful thing you can do is to forward this episode to your friends and family and leave a five star review on Apple Podcasts. These reviews really do help people find the podcast and the more people listen, the greater the impact of this grassroots movement to break down the patriarchal structures in our institutions and our relationships and build egalitarian structures in their place. Thanks again for joining me, and make sure to tune in next time for another fascinating episode on Breaking Down Patriarchy.

maybe the police are on your side

but for how long are the police on your side?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!