“we’re human, we’re all capable of this”

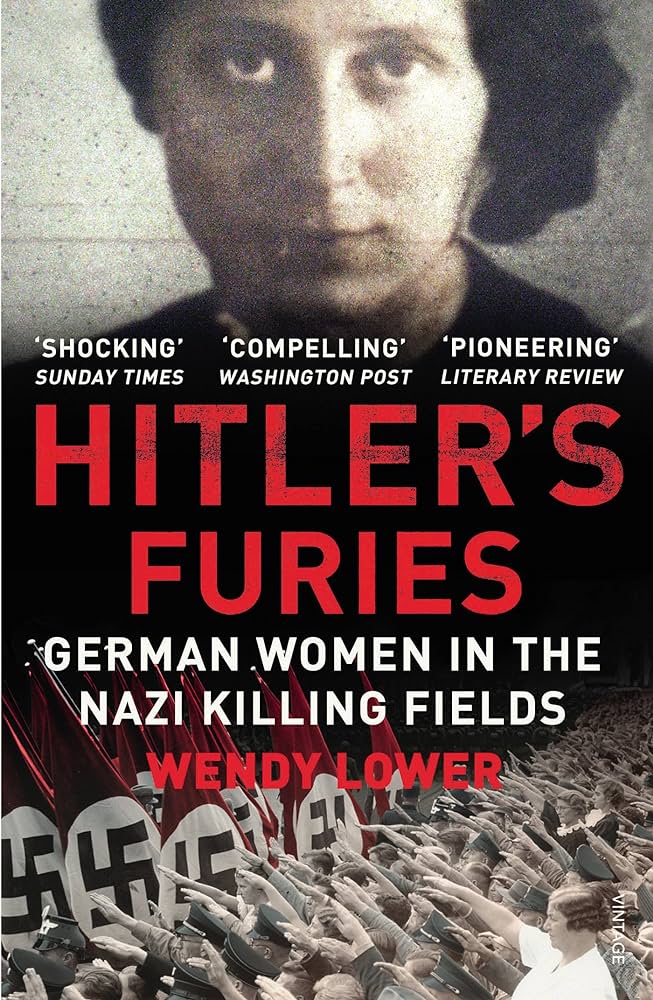

Amy is joined by Dr. Wendy Lower to discuss her book, Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields, and begin unpacking the complicated history of women’s involvement in the Third Reich.

Our Guest

Dr. Wendy Lower

Wendy Lower is an American historian and a widely published author on the Holocaust and World War II. Since 2012, she holds the John K. Roth Chair at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, California, and in 2014 was named the director of the Mgrublian Center for Human Rights at Claremont. As of 2016, she serves as the interim director of the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

Lower’s research areas include the history of Germany and Ukraine in World War II, the Holocaust, women’s history, the history of human rights, and comparative genocide studies. Her 2013 book, Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields, was translated into 21 languages and was a finalist for the 2013 National Book Award in the nonfiction category and for the National Jewish Book Award. Lower’s The Ravine: A Family, A Photograph, A Holocaust Massacre Revealed (2021) received the National Jewish Book Award in the Holocaust category and was shortlisted for the Wingate Prize, and longlisted for a PEN.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Groundbreaking women’s historian Gerda Lerner wrote a lot about the exclusion of women from humanity’s official history. She says,

“Women are and have been central, not marginal, to the making of society and to the building of civilization. Women have also shared with men in preserving collective memory…

History-making, on the other hand, is a historical creation which dates from the invention of writing in ancient Mesopotamia. From the time of…ancient Sumer on, historians, whether priests, royal servants, clerks, clerics, or a professional class of university-trained intellectuals, have selected the events to be recorded and have interpreted them so as to give them meaning and significance. Until the most recent past, these historians have been men, and what they have recorded is what men have done and experienced and found significant. They have called this History and claimed universality for it. What women have done and experienced has been left unrecorded, neglected, and ignored in interpretation. Historical scholarship up to the most recent past has seen women as marginal to the making of civilization and as unessential to those pursuits defined as having historic significance.

Thus, the recorded and interpreted record of the past of the human race is only a partial record, in that it omits the past of half of humankind, and it is distorted, in that it tells the story from the viewpoint of the male half of humanity only.”

I had always imagined these unwritten, unexamined women’s histories as being enlightening and inspiring. Never had it occurred to me that perhaps some of these overlooked histories would include accounts of women’s violence and sadism. And yet, this is precisely what happened in the history of the Holocaust.

Gerda Lerner herself was a survivor of the Holocaust, a Jewish Austrian who fled the war as a refugee. And I know she would be fascinated by the book Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields by Dr. Wendy Lower. This book brings to light the fact that women were much more involved in the Holocaust than is widely known, and I’m so honored to be able to talk about this book today with the author, Dr. Wendy Lower.

Welcome, Wendy — it’s so great to have you here today.

Dr. Wendy Lower: It’s great to be here.

Amy Allebest: So we’ll just start off by reading your professional bio and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourself a little more personally afterwards. Wendy Lower is the John K. Roth Professor of History at Claremont McKenna College and a former research associate at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. A member of the academic committee of the U. S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, she has published numerous articles and books on the Holocaust and conducted research in Central and Eastern Europe since 1992.

So, that’s just a brief bio, but Wendy, if you could introduce listeners to yourself, for example where you’re from, maybe a little bit about your education, and what brought you to do the work that you do today.

WL: Great, sure. Thank you so much and thank you everyone out there who’s listening and interested in these issues and this history.

I grew up in America, I grew up in the Northeast in New Jersey and Connecticut. Actually, my dad worked in New York for Singer Sewing Machine Company (that’s a company that a lot of people probably don’t even remember). And I came to this topic actually as I was growing up in America in the eighties, late seventies, I was born in 1965. I experienced the miniseries, ‘Holocaust’, in 1978 — it kind of blew my mind. I was 13 years old at the time and I just started to kind of witness the history. I mean meet survivors studying abroad in Austria as an undergraduate, studying German and History there in Vienna…Kurt Waldheim was running for president. The scandal of his past came out, his Nazi past, this former UN Secretary General ran for president and actually won the election. And you know, going into these different environments in Europe seeing the remnants of the camps, talking to veterans of the war, realizing that their stories were not only about the front line, but also about genocide stories, and that I found very confusing. But mostly interacting with these former male perpetrators and veterans of the war…The collapse of the Soviet Union coincided with my decision to go to graduate school, and so I ventured into Ukraine and this terrain realizing that this was an understudied region for some of the worst crimes and genocides of the 20th century, including the Great Famine that Stalin inflicted on the Ukrainians in the early thirties, followed by the war and the Holocaust. And then today, of course the struggles continue there.

So yeah, it was part of the kind of progression of events in my life with this kind of deep interest in the history of Germany, the Second World War, Nazism, and the Holocaust. I also had the opportunity to work at the Holocaust Museum doing my graduate work at American University under a very eminent scholar of the Holocaust, Richard Breitman, who had just finished a biography of Himmler. I needed to pay the rent and I found a research position at the museum, and so that brought me into the world of history through various media, through artifacts, through photographs, obviously captured German records, so it was expanding my kind of sense of methodology and bigger questions. Big, big museums like the Holocaust Museum have to deal with audiences that ask those big questions like how, why, where, when and that’s really what brought me to Hitler’s Furies, because I realized that some of these bigger questions were not being posed vis-a-vis women’s history and history of genocide.

AA: Well, that’s a perfect bridge to just dive right in because as I mentioned in the intro, the stories of women in the Nazi killing fields were just not told really prior to your book. And if it’s okay, I’ll just read a sentence or two from the book. You say, “the consensus in Holocaust and genocide studies is that the systems that make mass murder possible would not function without the broad participation of society. And yet nearly all histories of the Holocaust leave out half of those who populated that society as if women’s history happens somewhere else.” So that was just a really powerful, eye-opening way to even start the book, and it leads me to the question of how German women had been depicted prior to this history that you wrote. What was the official narrative about women’s participation?

WL: When I came to this, I was building on the historiography of mostly my foremothers because most of the history was being written by women, by female historians, and they were not a large influence in that way. It was mostly a male profession, and so the profession is dominated by men, then maybe these questions are not going to arise. So the work of Claudia Koonz was really important for me, Mothers in the Fatherland, Atina Grossmann, Marion Kaplan, others working on Jewish female victims and the Jewish family.

these bigger questions were not being posed vis-a-vis women’s history and history of genocide

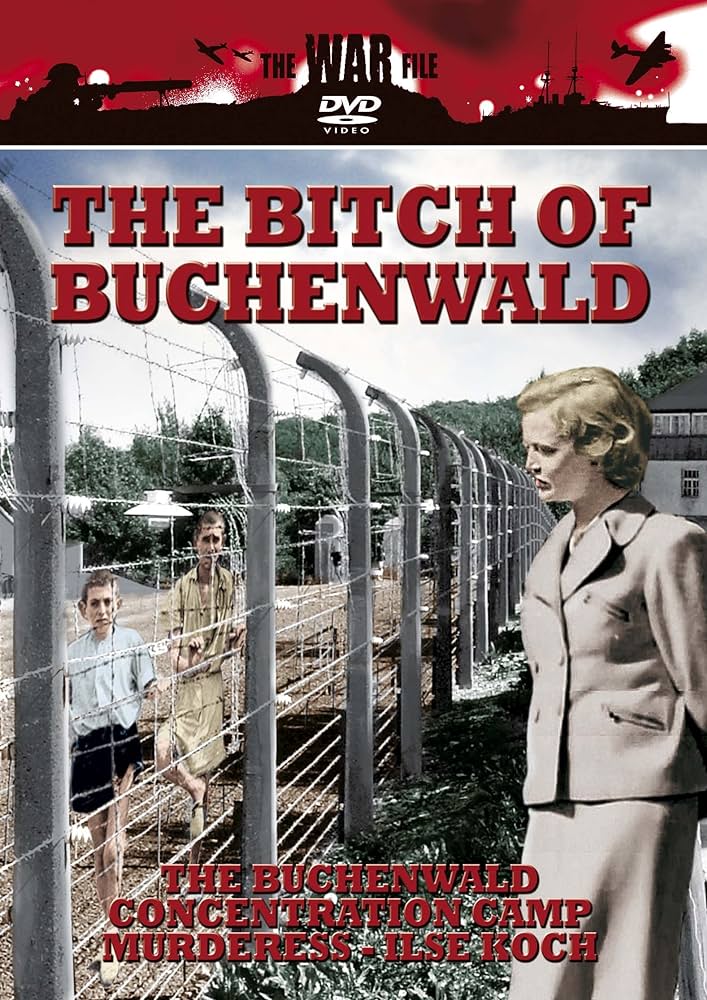

So there had been quite a bit, I think, about what was going on with German Jewish women’s history. That was one angle. But for German women as a kind of whole and interrogating to what extent they saw things, the crimes of the Holocaust, or participated in them, right? These kinds of things were not really coming out. They were seen not even as accomplices, but as kind of morally propping up their mates as being a justification for the killing in a gendered way. Or they were peripherally, even in a freakish way, consigned to these kinds of caricatures of perpetration, so their evil was eroticized. They were even in a pornographic sense, and they were subject…I mean German women became subject of these pornographic films after the war. So that was reinforced by popular culture and those representations: they were either freaks of nature which kind of put them outside of the community, of the history, or the other depiction was they were camp guards, so they were in uniform.

Again, the eroticization of their evil was part of that — The Bitch of Buchenwald — all these kinds of depictions. But in relation to your earlier comment about women being outside of history, the implications of that when you’re talking about the history of genocide are really significant because Ann Taylor Allen, whose work I really admire as well, she said that when they remain in the female sphere, when we think of women’s history as these two spheres, the private and the public they are endowed with an innocence. That’s the other projection: that they’re nurturing, they’re kind, they’re caring, they’re innocent. And when they’re endowed with that innocence then they are standing outside the crimes of the modern state and modern society where they’re clearly participating. So they’re outside modernity and then they’re kind of outside history itself. So that’s the logic, the implications of approaching them in this kind of separate way.

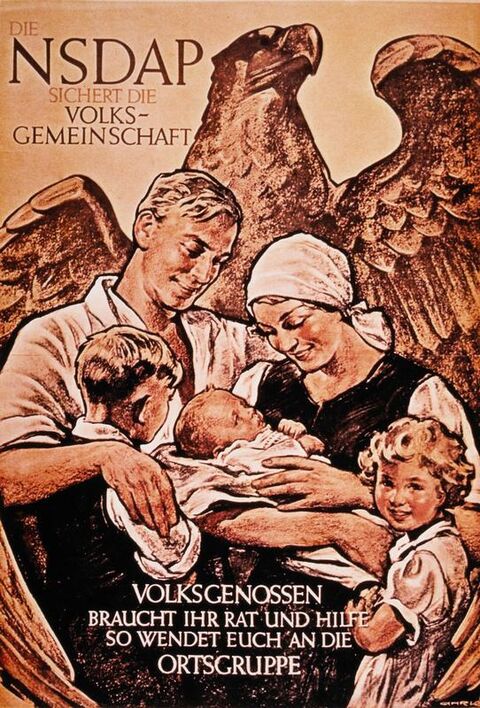

AA: So what I’d love to do is go through the book chronologically, and my first question was what you were just talking about; it was going to be how women were portrayed by the Third Reich. And my understanding is that that was very much how Hitler and the ideology of the Third Reich did portray women is the ‘angel in the house’ and you’re supposed to make babies for the Reich…and if you could just talk about that just a little bit to set the stage for us.

WL: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, we see in Hitler, in Goebbels specifically, in the way these things are rendered, these Aryan figures and these farm-like maidens. And of course they’re surrounded by the babies and they’re coddling the babies. And so it’s this notion of a procreative source for the Reich because it’s a racial regime. Remember that this is completely a revolutionary movement that is pushing for a racial regime that is considered legitimate at this time. Racism had not been fully discredited. This was the full extent of it coming out of the 19th-century of scientific racism and now racism as a state ideology. So women are going to fit into that mode in a very biological sense as a kind of procreative force and notions of purity and chastity and loyalty and devotion to the cause.

But these are projections. This is propaganda, is kind of wish fulfillment. It’s not reality. And even though Hitler said that women’s place was in the home as well as the movement, and that they were going to play this kind of secondary role to support the men, he also used a lot of the martial rhetoric of society being really important as well; kind of women in uniform now that he also calls them our most loyal, fanatical fellow combatants. So they are mobilized to be part of a revolution in a way that they feel like they’re going to fight the fight for this Nazi cause. After 1935, the birth rate declined in Germany, the divorce rate increased and statistics show that most German women were not married and they weren’t constantly pregnant and they weren’t staying at home. So the reality is quite different from these projections. And when the women are mobilized for this revolution, how far can they go? Cause this is part of a general era in the interwar period of the politicization of women. Women are getting the vote in America. They got it in the Soviet Union. They’re getting it in Germany and they’re coming out into the public sphere and being part of these totalitarian movements. So once you open that up for women and bring them into the public sphere in that way and mobilize them. They’re not just bodies to be ordered, and paraded through; they start to become very influential. They start to work in the offices, show up in the kind of war zones, literally, and be a part of the very implementation of the crimes of the regime.

AA: Another aspect of the setting of this story that was really new to me you referred to a little bit in the introduction, and that is that it takes place in Eastern Europe and Ukraine. Prior to reading your book, Wendy, I had never thought about Ukraine’s involvement in the war nor had I any idea that it was a site of such brutal genocide, really. So I wondered if you could just say a couple more words about that and just kind of describe the geographical location of what you refer to as the ‘Nazi killing fields’.

WL: Yes. And bear in mind too that this is a moment in our understanding of genocide as I’m kind of putting this book together and experiencing the 1990s experience — the Balkan crimes in the Balkans, sexual violence in the Balkans in Srebrenica, and this mass murder — that’s not industrialized Rwanda 1994, people talking about Cambodia in the seventies, and the references to killing fields. And so this is very interesting that that understanding of genocide, not as factory style (you know the way the Nazis industrialized it) but as killing fields, as mass murder in broad daylight in rural communities where the mass graves are covering the landscape, basically, and this is what happened in what Tim Snyder calls in his book, “the bloodlands of Eastern Europe” and what Father Desbois calls the “Holocaust by bullets”. One out of four victims of the Holocaust who died in Ukraine died outside the camp system. These are the people, the mobile killing units, the so-called Einsatzgruppen invaded in 1941. This was the big war. Hitler was determined to eliminate what he called Judeo-Bolshevism — the Soviet Union from the continent of Europe and beyond — and had this utopian view of Eastern Europe as a living space for Aryans, the so-called ‘Laban’s realm’. His deputy, the head of terror, Heinrich Himmler, calculated that something like 30 million indigenous kind of Slavic peoples would disappear over the course of a few decades, starting with the Jews, deemed their greatest threat.

And so this campaign in 1941, the summer of 41 invasion of the Soviet Union was when the mass murder began. And it began when the mass gassing facilities had not been established yet in Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz-Birkenau. So it raises all kinds of questions when you think about women’s participation, if they’re not formally enlisted in as camp guards in uniform, but you have this history of genocide happening in these settings where women are arriving as part of the occupation administration, they’re being mobilized. About a half a million or are circulating in these zones, like then they’re suddenly in these spaces of mass murder. They can’t be back home on the home front, innocent of the crimes, propping up their men in the traditional way that you think of war as a home front there. They’re in that space. So what do they see? What are they doing? You know, how are they responding?

AA: Yeah, so you talk about women at first in the book as three specific professions that participated in the Holocaust, and I must say, I was really surprised to see listed these three professions of women. You talk about teachers, nurses, and secretaries. Could you talk a little bit about each one of those professions?

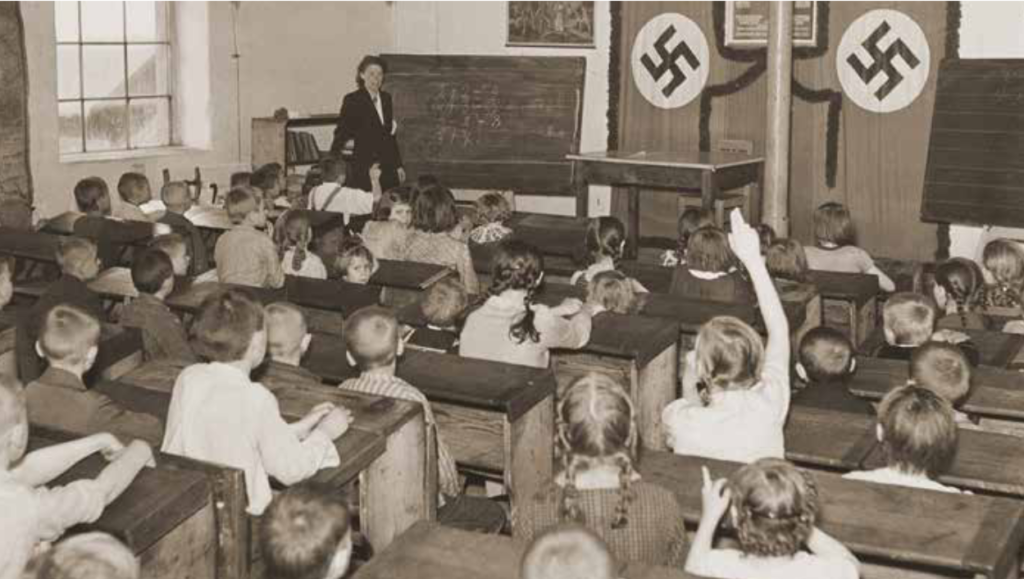

WL: Sure. I mean the teachers, of course, this is considered a female profession and it’s key to the regime as far as socializing future generations and the youth. And so education is a key feature. Women are brought in to go to the east to set up these schools for the ethnic German population. Even like one room schoolhouses that kind of set up one of thirteen biographies in the book that I think are representative of half a million women. Basically it’s like the spectrum of participation and reaction, and one of them is this teacher who’s in Poland in a kind of one-room schoolhouse. So, single women between the ages of 18 and 25 had to perform their labor service period. So it was necessary for the regime and for it to accomplish its goals, especially with all the men on the front in combat.

So that was one of the professions that women populated and was even expanded to these occupation zones. And in the case of the woman featured in the book, she encounters these Jewish laborers who had fled from the local camp trying to flee a deportation and they appear in the schoolyard and the kids — their reaction to them, to these men who are in tattered clothes, are desperately hungry, unclean and all of that are, are threatening to them — and she’s in the schoolhouse, and she hears a commotion outside, and the students are attacking these Jewish men and throwing rocks at them and acting out violently. So that’s how they respond, and there’s… I don’t have a story as far as her direct participation in the killing, it’s just an example of the presence of the women, and the society that they’re in, these kind of German-only societies and how it intersects in a daily way, in that capacity and we also have teachers who are both back in the Reich and in the school, how schools in the occupation zones who participate each day because they’ve internalized the kind of racism and eugenic movement in selections. So they’re observing the students since the midwives are doing this from the moment of birth, checking for so called racial defects — anything from epilepsy to whatever they considered kind of congenital diseases, are the parents alcoholics — so these teachers take on these roles, especially cause a lot of the teachers were Nazi party members. That was part of the program to kind of a qualification.

So yeah, this is how these regimes take root and how selection happens in this very kind of intimate quiet way. And people start disappearing. It’s incredible how much power can be wielded in these different environments, and that’s another point of the book, is to think about where genocide happens in all these different settings. Like domestic settings, killing fields, selection in schools, selection in hospitals, midwives, nurses, obviously in the euthanasia program administering lethal injections; the ways that women’s normal roles of nurturing were perverted in that way, that the trust that these children had in these women that they assumed were going to take care of them and didn’t in the end.

Yeah, as nurses, as teachers (very important) and as secretaries because this genocide, when you look at the work of people like Raul Hilberg, the machinery of destruction and the magnitude of it is we can interpret that as part of this administrative monstrosity. This machinery of deportations of selections of 10,000 police stations and tens of thousands of civil administrators and their fiefdoms and their clerks and their offices. So female secretaries played an incredibly powerful role. I would say for me, one of my biggest discoveries — because these sadistic kind of perpetrators are in the minority, and in these regimes they wield a lot of power — these marginal kind of elements can participate with impunity and their acts of violence. But I think the fuel that generated the kind of magnitude ultimately of this Holocaust of 6 million is the machinery, as Raul Hilberg put it. And that means a lot of these clerks who don’t see themselves as genociders are doing their jobs. It’s all kind of a division of labor. You check off this list, you move this document over here, you order these bullets, you make sure that the men have nourishment if they’re going to be in a killing squad all day, you sort through the Jewish property here in this bureau…and this is where women made a huge impact. And when they were in the Eastern territories they were maybe pushing paper or typing up orders. Even meeting with heads of the Jewish community in the front office, cause they were like executive secretaries.

When they were in the Eastern territories, they knew what the outcome of their work was. They weren’t back in Berlin kind of wondering what happened to the Jews who ended up in Belarus or the Baltics. They could smell, they could see, they knew exactly what moving one file into their boss’s office was going to result in. And of course, this is a continental empire. They’re not sent overseas and not at home for years, like some of our service peak personnel who were sent to Europe in ’44, ‘43 even. People are moving back and forth, and so I think this whole notion that ordinary Germans back home didn’t have a clue is also a part of a kind of post-war suppression.

They could smell, they could see, they knew exactly what moving one file into their boss’s office was going to result in.

AA: That was really fascinating to me that a lot of these episodes that you highlight in the book, for example, the one that you mentioned with the school teacher just seeing these people trying to flee, and they’ve just run, just by coincidence, run right into her schoolyard so she sees the war in her home environment, and then sometimes (and we’ll get to this in a minute) but literally in people’s homes, like outside in their yards and in the streets, or they’re looking out a window and they see these atrocities happen. That’s also something I’d never considered.

WL: I mean, even in the case in Buczacz, Omar Bartov wrote a brilliant book about Buczacz and he gave me some documents about that, about the head of that community, the German civil administrator and these administrators who came with their families. It’s also really important that they’re sent there to set up these German-only communities and take over the nicest properties in town and so forth, and they’re these colonizers and they’re self-fashioning as kind of frontiers people and drawing a lot from American history, these kinds of tropes.

In that case, I remember the wife of the head administrator…this child is coming home from school and there’s a dead Jewish woman on the street, like in a pool of blood, and the mother is like, ‘get this mess out, I can’t have my child walking over from school, like stepping over this.’ And so again, the intersections of this history and kind of an everyday life and how that would be maybe an everyday question for the person encountering it, who’s not supposed to be kind of officially involved, but is confronting it and imagine that, imagine the child saying, ‘well, what is this?’ Or the other wife, saying openly ‘this needs to be cleaned up’, but what is she actually thinking, right? Where’s her moral compass?

AA: Yeah, that was something that happened over and over in the book where I would have to kind of stop and put it down and just think like, what would I do in these circumstances? And especially…so I am a teacher. My sister is a labor delivery nurse. And again, professions and situations that I’d never thought of before: like what if I were a teacher and then I were given this curriculum, this racist eugenics curriculum, that I had to implement on fear of my life, right?

And just being part caught up, I guess, in this machine that’s happening or like you mentioned, the nurses that were put in a position where they were taught that it was, humane to ‘euthanize’ children with disabilities or children who in some way didn’t meet the criteria of this racial purity anyway, but just thinking like…what would I do?

And so that brings us to the next part of the book where you divide into three categories and you do these wonderful character analyses of women who were in three different categories: witnesses, accomplices, and killers. I wonder if you could maybe bring to life an example or two in each of these categories.

WL: One of the examples that just sticks with me and is for the witnesses category (we’ll start with that) is Annette Schücking-Homeyer, the nurse who was sent to Novohrad-Volynskyy, which is near Zhytomyr and is in Ukraine, central Ukraine. And she was very educated, well educated. She came from a long line of literary figures going back to the 19th century. Her father was a social democrat, so he was more progressive and anti-Nazi, and a journalist, and he had been persecuted from the very beginning in 1933 when Hitler was appointed chancellor.

They started to Aryanize the professions and get rid of their opponents politically, but she was idealistic. She said, ‘I’m going to pursue my law degree’. And she managed to do that actually, even though there was strict quotas and women couldn’t be judges. But she did manage to do that in Münster and then, because she was so poised and educated, she was assigned to these soldiers’ homes. There were about a thousand of them, and these were places where the soldiers could stop and get German cooking and interact with cultured German women. And so, although she was nominally in the German Red Cross and wore that uniform, she wasn’t trained in medical procedures. She just had this kind of care-taking role for the soldiers. But of course, being in that place at that time, a couple of things happened. First of all, as soon as she arrived, she got a tour of the town, and this German soldier just kind of matter-of-factly pointed to the Sluch River and said, “Oh before you arrived, we shot like 500 Jewish people here on the edge of the river.” Again, the Germans are using the natural environment a lot to accomplish their goals outside the killing centers. They’re using ravines. They’re using swamps. They’re using rivers. It’s another part of the story that’s interesting too.

In any event, Annette is shocked and she’s like What? This is not what I signed up for. And then of course the men who are coming into this social environment that she’s facilitating are telling their stories, their genocide stories about rounding up Jews in one location and keeping them in a building where they’re suffocating and they’re weakening them in that way for several days before they shoot them, talking about their killing methods. Annette writes back to her mother, “What Papa says is true. There are killers here and this place, it smells of blood.” That she’s just in the midst of this bloodbath and she doesn’t know how to get out of it and she feels powerless. And when I interviewed her she was still in her elderly state, like “Wendy, I just felt so powerless.”

But what she did do, remarkably, was she collected the evidence. She was a good witness. She was a good observer. She had that law degree. She had a sense of justice. She became a judge. One of the few female judges in West Germany after the war. And she contributed to the prosecution of people within that region. She was sending material. I ended up finding it in the investigators’ offices in Ludwigsburg; there was her name. She had people come into her court as a judge after the war whom she recognized, who were genociders during the war, and she said, “I have to recuse myself.” And then she reported on them.

So she couldn’t do anything at the time, but she really dedicated her life after the war to women’s issues, and also the pursuit of justice as far as what she had witnessed…Annette Schücking-Homeyer. So, a very interesting biography.

And then for the accomplices, as I mentioned, these secretaries…Liselotte Meier is a wonderful example in Belarus in Lida, where 15,000 Jews were killed. And she not only was this executive secretary and making sure everything was all orderly and documented, but she developed a relationship with her boss, which is kind of interesting because I think a lot of her ambition and her attention to detail was also because of this relationship and she was just so enamored with her boss that she wanted to be working towards the fuhrer in that regard, that notion. And so, yeah, she helped organize those mass shootings in ‘42, ‘43, as his secretary. Then after the war, she was brought in and interrogated about the crimes of her bosses. Her immediate boss whom she was having the affair with, Hanweg, he was captured by the Red Army and disappeared. Presumably he was killed. He never came back and this story continued because her daughter, after my book came out, read about her mother and I did through a journalist… I did get their private collection of her mother’s letters and did confirm a lot of the participation of the mother and certainly the relationship she had with her boss.

And yeah, when she was interrogated by the West Germans about the crimes of her boss and was crying during the interrogation (this is now in the 70s, late 60s) the prosecutor noted that she was crying and didn’t have an explanation for that, and part of me thought when I read that that maybe she was feeling some remorse for what happened, or those were just…it was another chapter that she didn’t want to confront, and was emotionally overwhelmed, but then I realized that she was actually crying because of this lost love, because of this more emotional kind of…her first love. And so it’s just another example of the value of the Jewish life, because during her interrogation, even post war, she said they were dreck, they were the scum of the earth, she was still speaking in anti-Semitic terms. And that was a reflective manifestation of what it was like at that time. They were there to be used in the workshops to create furs and jewelry and they were part of their courtship. They were building the swimming pool. They were serving them delicacies after they made love. This was her world. They were going on recreational outings and Jews were laborers, were seen along the road one winter when they were in their carts on a Sunday afternoon. Liselotte Meier and the rest of the German community there, they were out and they saw the Jews, Jewish laborers, and they started shooting at them like they were rabbits. So that whole German-only community in the East was also part of this debauchery, this exploitation of Jewish laborers and these kinds of intimate relationships. That was their world. Those were their days, their good old days…

And then the perpetrators. Of course, Erna Petri is the most outstanding case in the book. Really one of the reasons why I wrote the book. And that is an example of someone who really, as she said, “I believed what was told to me about the Jews and the threat of the Jews. Everybody in the region was doing it. I want to prove myself to the men.” That weird, perverted sense of self-assertion, what you might say is feminism, empowerment, is now being wielded in this way. Right?

Erna Petri brings those Jewish boys who had fled the boxcars to Belzec to her kitchen, feeds them, calms them down like a nice mother. Her husband doesn’t come back. She’s got a gun. She’s on the wild frontier there and she just mimics the husband and marches them to their little killing site on a gully on their property, on their plantation as a kind of…set it up there and shot them in the back of the neck, each one of them and confessed to that after the war in 1962, ‘61.

AA: Yeah. One thing that was interesting to me was when we’re thinking about the three categories: the witnesses, like you described, this woman who thinks, I mean, I can’t stop it. And these people who would look out their windows and see people just being marched down the street to their death, and just weeping as they’re looking through the window and thinking, even if I ran out to try to stand up to them, they’d just kill me and I couldn’t save anyone anyway. There’s just nothing that they could do in the moment. And then you have the accomplices that you just described, like this woman having an affair and really just greasing the wheels, doing everything that she can to kind of help the work along. So definitely beyond a witness. But then this last category, you say, these are women who did way more than they were required to do. It wasn’t just that they had to do it or they would be killed or something like that. They went out of their way to it was like sport for them or they got a thrill out of the killing.

And that was that last category of killers that were just really cold-blooded and in a way that I couldn’t even imagine. And this is one of the things that really complicated the narrative of women because we… I mean, I do too, I think of women as more nurturing and less violent than men. And so I wanted to ask you about that and whether over the course of your research, did you change your personal view about maybe differences between men and women being…I mean, there’s always a debate about what’s biological versus what’s environmental and socialized, but this really complicates the narrative, I think, for a lot of people about women not having those violent tendencies.

WL: There are a lot of assumptions when we come to women’s history, and I don’t think those are so bad. I mean, some assumptions of nurturing, of being the caring caregivers, of maybe being ethically or morally somehow, as a result, superior to men, right? Because if you are the child bearer and from the beginning you’re socialized in that way to protect life and the life of that child and the safety of that child, and again, it’s a biological, emotional, socialized kind of experience. The assumption is that you’re going to be the force for life, right? You’re the life-force. And in fact, that assumption is why women are targeted by genociders. Because if they’re the procreative force, in order to eliminate the enemy population, you have to prevent that. So, like 200,000 German women were sterilized, so they were also victims of the racial regime too, because the Nazis didn’t want them to procreate. They were considered genetically inferior, so they’re forcibly sterilized. And for the witness who might have gone out and tried to intervene in that way, or even not even openly, but quietly sabotage, and acts of resistance…Yes, they would be persecuted. Some 8,000 female communists, socialists, pacifists were considered political enemies of the Reich and asocials. And they were prisoners in the camp system too often, block leaders and so forth. So, they wouldn’t be killed per se for resistance in that manner. They’d be considered just kind of outside the bounds of the system. So, it’s an interesting scenario for these regimes that unleash or allow for women to act out in these ways.

200,000 German women were sterilized, so they were also victims of the racial regime too

It’s not that they’re incapable of it. I mean, we’re human, we’re all capable of this cognitively, emotionally. I mean, it’s all there. It’s just really the way that we’re kind of socialized and what’s in the conventions and what you can physically kind of do. Because let’s be clear that these genocidal campaigns, and the way like the mass shootings and you hear this about the Rwandan case too…it was hard labor. It’s terrible to say, but it’s incredibly “difficult work” to carry these things out. So they did physically play more of these kind of secondary roles. But of course, we keep fine tuning these methods as well. That’s why women, I think as genociders, their greatest role was as nurses because that was something like…luminal pills could be administered, injections could be carried out and the murder could be accomplished in that way. It was not physically standing up with a gun. So, it definitely opens your eyes to our bias. Our assumptions.

Like I was saying, kind of inferring the beginning, sometimes those assumptions are good because you can hang onto that hope. You can say, “okay, at least there’s a segment of the population where we can invest, invest or expect that kind of behavior from.” So it might actually guard against these spiraling cases and the escalation of the violence. But in fact, it’s nothing we can really count on. Because we can see that this capability also exists and having kind of grown up in the latter part of the 20th century influenced by my foremothers — my grandmother, my mother, kind of then extending back in time of the late 19th century, as far as family history and memory the idea of feminism as something progressive, the force for equality, the force for change is more democratic, progressive, the welfare state, kind of a liberal cause — that was shattered for me as I went into this history because I realized that that is not the case.

And we see that more and more. We see women in the KKK. We see women fanatics in the Taliban and I’m sure in Hamas in various roles. And of course, here in America we have extremism on both sides, on left and right, but increasingly women very openly in the Republican party taking pretty extreme positions that we wouldn’t expect as well in the name of ‘making America great’ or what have you. So yeah, they’re found across the political spectrum. And that’s just an important reminder of we women who are essentially human.

AA: Yeah. Well, that’s been one of the major themes, I guess, as we’re talking about it, of this whole season, as I’ve talked with women all around the world and hearing so many feminists. I mean, I guess they would…well, I won’t even say feminist. They wouldn’t call themselves feminist because in a lot of places feminism is, they say, for white people. And the image that came to my mind just now is the plantation owners, wives of enslavers, right? And their cruelty. It really reminded me of some of the scenes that I read in your book where these women, like you said earlier, would have their own children. They loved and nurtured their own children, but then had so absorbed and embraced this horrible racist ideology that other people’s children didn’t consider them human or worthy of nurturing.

WL: Well, we see that the hypocrisy is all over. We see these are women too who would self-identify as God-fearing Christians and will be citing various parts of the scripture about charity and care and the Good Samaritan. So we all have this ability to split as far as what we think is within our community, how we treat one another, and be selective about that and not approach it in a universal way. Especially at this time when, again, racism had not been fully de-legitimized, it still hasn’t. I mean, it’s a very complicated history, but particularly in the Nazi history when it’s just so overtly and proudly a racial regime and a racial experiment and the extent to which they implemented that, and obviously with the Holocaust…So I just wanted to bring that up because there have been some discussions recently that there’s no connection between racism and antisemitism and questioning to what extent the Nazi regime was a racial regime and confusion about that because it doesn’t necessarily involve kind of what we think of as a Black racism, but trying to understand racism. And as you look at it more globally, how it operates…Yeah, we have a very American-centric view of the history of racism.

AA: Well, we hit all of the bullet points. It was fabulous. So is there anything else that you’d like to add or any takeaways?

WL: I guess one thing I would want to say is…because I think your podcast…I just want to credit you or just draw attention to the fact that you’ve taken this global tour. I mean, in light of what I just mentioned about racism, and it’s really important to look at women’s history in a global way, a global historical way, because many things we’ve been talking about today, as far as these biases and kinds of expectations of women are so culturally constructed. An in some ways, the lack of women’s history started with not thinking that women were fully human. And some of the earlier feminist writers pose that question, like, “are women actually considered human because of the way they’re so mistreated?” Whether mass rapes and discrimination and so forth and female genital mutilation…So the victimization of women to such an extreme that they are just kind of objectified in that way. And once we come around to the realization that they are fully human, then to raise the standards of what we expect from women as citizens of the world and what their contribution is. And they’re not apolitical. They’re not cheerleaders, secondary figures, and accept that power and think about how you wield it in the world and think about agency and in all its complicated ways that it’s not all about the public realm per se, that these realms are blurry and to be more self-critical, more self-reflective as a woman in the world. What are you doing for your community, for your sisters, for your family members? My students and obviously younger generations now who have been empowered by the Me Too movement and so forth?

So it’s not as if women don’t embrace their political activism in that way and fight for their rights in all different ways. Yeah, a little bit of self-reflection and critical analysis, critical thinking about our history and what we need to own up to, what we need to be accountable for, whether it’s the history of slavery and the role of the wife and the plantation system, but let’s go back and really take into full account our record.

AA: Hear, hear. Well, thank you so much, Dr. Wendy Lower. Again, the book is called Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields. I learned so much and thank you so much for being here for an episode of Breaking Down Patriarchy today. Really, really enjoyed it. Thank you, Wendy.

WL: Thank you, Amy.

What are you doing for your community,

for your sisters, for your family members?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!