“you can celebrate women…but it is nearly always through a male lens that you’re doing it”

Amy is joined by Dr. Sue Blundell to discuss her book Women in Ancient Greece and explore the roles of women in ancient Grecian society as well as representations of female deities.

Our Guest

Dr. Sue Blundell

Sue Blundell is a playwright and lecturer in Classical Studies. Many of her plays have been inspired by ancient myths, ideas, and objects. More recently she’s been exploring the lives of artists and composers, such as Auguste Rodin and Benjamin Britten. Interaction between actors and musicians has become a vital element in her work. Sue wrote her PhD thesis on Greek and Roman philosophy; more specifically, on Epicurean ideas about biological and cultural evolution. She has been a lecturer in Classical Studies at the Open University, Goldsmiths, and Birkbeck, University of London, and has given regular lectures at the British Museum. She also taught for a number of years on the Conservation course at the Architectural Association School of Architecture. Her main area of research is the history of women in ancient Greece, and their representation in drama and the visual arts. Her other writings include work on Greek and Roman theories of evolution, Emma Hamilton’s ‘Classical Attitudes’ and their place in the 18th century Grand Tour, and the symbolism of shoes in Greek art and thought. She has presented conference papers at universities in the UK, Europe and the US, and has been a keynote speaker on Greek footwear.

Sue is currently working on a book provisionally titled Finding her Feet: Female Footwear and its Stories

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: If you open the book, The Second Sex, to the very first page after the title, you will find that Simone de Beauvoir opens her famous treatise with a quote from the Greek philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras. The quote says, “There is a good principle that created order, light, and man, and a bad principle that created chaos, darkness, and woman.” Here in the Western world, we can trace the ancestry of our philosophy and our government and our art and our psychology, and in many ways, the way in which we see ourselves and our world largely to ancient Greece. I’m very excited to discuss the classic text, Women in Ancient Greece, with the author Sue Blundell. Welcome to the podcast, Sue! I’m so excited to have you here.

Dr. Sue Blundell: I’m very pleased to be here. Thank you for inviting me.

AA: I’d like to start with your professional bio and then have you introduce yourself a little more personally. Sue Blundell is a playwright and lecturer in classical studies. Many of her plays have been inspired by ancient myths, ideas, and objects. She wrote her PhD thesis on Greek and Roman philosophy, more specifically on Epicurean ideas about biological and cultural evolution. She has been a lecturer in classical studies at The Open University, and Birkbeck, University of London, and has given regular lectures at the British Museum. Her main area of research is the history of women in ancient Greece, and their representation in drama and the visual arts. She has presented conference papers at universities in the UK, Europe, and the US, and has been a keynote speaker on Greek footwear, which was so interesting to me. I’d love to hear a little bit more about that, Sue. So, if you could introduce yourself to us on a more personal level, where you’re from, your family of origin, and what got you interested in women in ancient Greece.

SB: I’m from Manchester, which is in the north of England, but I’m in London now. I went to college in London, and I’ve been here ever since. And it is a wonderful city, I have to say. I did Latin at school, we call them A-levels, and I decided to apply to do classics at university because, this is terrible, but my best friend was better at English than I was, but I was better at Latin. So, that’s why I chose classics. Isn’t that terrible? But I have never, ever regretted it. Because the alternative was for me to study what in those days we called English, they call it other things now. But I’ve never regretted it because the classics took me into all kinds of areas that I may not have got into otherwise: philosophy, art, architecture, history. And because it’s a multidisciplinary subject, it covers so much. It’s been great.

AA: Your book, Women in Ancient Greece, how did that come about? How did you get interested in women specifically?

SB: I was a 1970s feminist, as so many of us were. I’d left college in the 1970s and was working, and I started teaching at some point in the 1970s, and a lot of people started writing about women’s history. And in the classics at the time, lots of other people, certainly here and in the States, I know, were writing women’s history. But there was very little of it in the classics. And I was giving lectures at the British Museum at the time, and I was talking about women in myth in particular, and so it must have occurred to me then that I should ask the British Museum to publish a book, which they did do. They have their own press. That’s how it started.

AA: I’m looking at my copy and it says it’s published. My copy is published by Harvard University.

SB: Yeah, they had a deal with Harvard. They published it jointly, basically.

AA: Fantastic. My point of reference is Dame Professor Mary Beard. We read Women in Power on the podcast and reviewed that a couple seasons ago, and I learned a lot from that too. Was she already speaking about women in classics at that point as well?

SB: She wasn’t, because she must be about 10 years younger than me. Her career must have only just been starting at the time, I think. But she’s great. No doubt about that.

AA: Yes. Well, you’re great too. I enjoyed this book so much. I was just telling Sue, right before we started, that my oldest daughter, Lindsay, just graduated from college with a minor in classics. And I’m going to hand your book to her first and then make all my kids read it. It was so fun to read. So, so very interesting. I just loved it.

SB: Thank you.

AA: So, listeners, pick up a copy and read it. And we’ll cover some of the highlights now. So if you don’t mind, I’ll start by asking, as a historian one important question is always to know where a historian’s sources come from. And you point out in the beginning of the book that there’s a challenge in writing about women in ancient Greece in terms of what your primary sources can be. Could you talk about that a bit?

SB: With some exceptions, most notably the poet Sappho, all ancient writers that have survived are male. So we are getting a male view on women. And of course, we’ve lost so much of ancient literature that our sources are really scanty. But that’s not to say that we haven’t got some good stuff, some very good stuff to go on. But we do always have to remember that ninety-nine percent of it is from a male perspective. But we have various sources, and certainly in some of them, women are very prominent. It’s often said that, in drama in particular, in ancient tragedy and ancient comedy, women are very big. You would never know that they were such a minority, politically and socially. They weren’t necessarily a minority, but they had a very low profile politically and socially, as far as we can tell. But gosh, they’re big in drama. It’s very interesting. So our sources are scanty, by and large male, but very interesting as well.

AA: And you point out, too, that we always have to take anything, if it’s from a male source, we take it with a grain of salt. That it means that was what the men thought was important about women, right? It’s what men were thinking about women, not what women were thinking about themselves. So it’s still a really important and interesting resource, but we don’t have almost anything about what women thought about themselves. The other thing that you point out was class. Could you talk about that a little bit, like what social classes represented?

SB: I think you would have to say, there are exceptions certainly, but largely they’re educated and very cultured people who are writing, by and large. On the other hand, we do have things like law court speeches, for example. Where sometimes quite ordinary, and I will say working class people, are being taken to court. If they have a speech written for them, because speeches tended to be written by professional speech writers, then we get some very nice insights into people who are not really at all posh, one would have to say.

The other thing you have to say about ancient Greek society is that these people may come from the more educated classes, the ones we hear about, the ones who are writing, but there’s one huge group of people who we don’t know anything about and that’s slaves. And of course there are a lot of slaves in ancient Greece and that’s a big gap. They kept slaves for a reason, obviously, and most of them were working in agriculture, so most of them were men. So most slaves were male, but female slaves were obviously working mainly in the home as nurses and housemaids and so on. But I think it’s not an easy subject to know about because people don’t talk about their slaves that much. But, you didn’t apparently have to be very rich to own slaves. It seems as though most Athenians were actually living off the land one way or another. Something else I should say there, Athens is the state in Greece that we know most about. Most Athenians were living off the land, and most of them would aspire to keep at least one male slave to help him work the land and a female slave to help around the house.

Another problem with our sources is that a very large percentage come from Athenian writers. Greece, at the time that we’re talking about, I’m talking anyway about the sixth, fifth, and fourth centuries BC mainly, and Greece was not a united country. It was divided into literally thousands of independent states. But the two of the most powerful states, not by any means the only ones with power, but two of the most powerful were Athens and Sparta. Sparta was not known for its literary achievements. It was a very militaristic society. But Athens had a very sophisticated cultural output. Athens was an amazing city state. And really an awful lot of our sources come from Athens out of all these thousands of city states. So we are talking about Athenian women a lot of the time when we talk about women in ancient Greece. Not entirely, by any means, but a lot of the time we are.

With some exceptions, most notably the poet Sappho, all ancient writers that have survived are male. So we are getting a male view on women.

AA: One thing I remembered from the book just now when you were talking, that was so interesting and completely new to me, was that because people got enslaved people from their conquests of war, if you defeated another people then you would decide whether to kill or enslave the men and then bring the women in as, like you said, household servants or sometimes to perform sexual functions in society. And so women had this awareness sometimes of like, that could be me. If we lose this war, I could lose my status in society and spend the rest of my life enslaved in somebody else’s house. I’d never thought of that before.

SB: Absolutely. I think one thing I should add is that up until the fifth century BC or BCE, before the Christian era, was a time of tremendous cultural production, particularly in Athens. In many ways it was a golden age, but it was an age of tremendous imperialism as well. And there was a kind of unspoken rule amongst the Greeks that you didn’t enslave your own people. It was seen as not very nice to enslave other Greeks. So they would enslave other conquered peoples, but not people who were Greek. But the Athenians threw that out of the window in the course of their imperialist activities in the fifth century. So they did on some notable occasions enslave other Greek peoples. But, come what may, if you weren’t a Greek, you were quite likely to find yourself enslaved in the course of warfare, and increasingly you might well be Greek and find yourself enslaved. But a philosopher like Aristotle, for example, thought that, and this sounds terrible and I don’t really want to put people off Aristotle…

AA: Oh, it’s okay. I’ve sufficiently put people off Aristotle in past episodes. Don’t worry. Go right ahead.

SB: He’s a great philosopher. He really is. But he thought that foreigners were natural slaves and Greeks were not. They were naturally free people, and it was a perversion for Greeks themselves to be enslaved.

AA: Yeah, I’ve put people off of Aristotle just for what he thought about women. But let’s begin by talking about myth, because that’s probably a subject that’s familiar to most listeners. We probably all had units on Greek mythology in elementary school. I always loved when it was time to study Greek mythology when I was a little kid. So tell us what we can learn about the ancient Greek conceptualization of gender by studying their myths.

SB: That’s such a tricky subject. I mentioned earlier that women have a big role in Greek tragedy, and the prominence of women in tragedy stems from the fact that women are very prominent in myth. And also I have to say, it’s a slightly different area, but women have an important role in religion as well. And that is different because women might have big roles in the worship of male gods. It’s on the level of a ritual rather than stories. But women in myth are the thing I always find most intriguing and quite difficult to get your mind around. Because in spite of the fact that women increasingly had no political power, and increasingly very little social power as well, we have these very powerful goddesses in Greek myth and they are very intriguing, I think.

On the level of the divinities, we’re dealing with some really outgoing females like the goddess Athena, the goddess Artemis, Aphrodite is powerful in a rather different area, that of sex and love, whereas Athena is a great military person and a great defender of cities. And Athena, who was the patron goddess of Athens but by no means the only place where she was worshiped, in many ways, she was masculinized. She was represented as a warrior, in the poems of Homer, for example, she’s a great friend of heroes. She loves hobnobbing with heroes like Achilles and Odysseus. So we tend to see her as quite a masculinized figure. And what we have to remember, and this is quite a different perspective on Athena, is that she was worshiped widely by women. And women would have felt a sense of closeness to her that we’re not really aware of because we get all these stories about her in Homer and in the Tragedians and many stories about her. But to sum up, the goddesses can be extremely powerful, and most of them do not present very good role models for women because they’re active in politics, they’re active on the battlefield. And this just was not true of ordinary women. It was completely unrealistic.

The other thing that intrigues me is that there are twelve Olympian deities. They’re the top gods and goddesses, six of them male, six of them female. And of those six female Olympians, three of them never get married and they’re virgins. And that’s a terrible role model to be presenting to Greek women because the one thing that was expected of them, of course, almost everywhere, almost always, was that they should get married and produce children. Virginity per se, lifelong virginity, was not seen as a good thing at all, for either sex. So it’s very strange that we should have these three powerful goddesses who are lifelong virgins. That’s Athena, Artemis, and Hestia, the goddess of the hearth. She’s more understandable. She’s very much associated with the home, Hestia stays at home, looks after the fire, doesn’t go out very much, doesn’t have any adventures. Athena and Artemis are always out, you know, fighting, hunting, mixing with men but not having sex with men. They mix with men, they like male company, but they don’t have sex.

AA: Yeah. And I remember that you talked about it in your book, and we also read it in another book called Unwell Women by Eleanor Cleghorn, that the Greek belief of menstruation was, well, they had all kinds of conceptions about why that happened. But as soon as a girl became fertile, it was like, “Quick, get her married because having sex will keep her healthy.” Basically the best thing you can do to prevent mental unwellness is to get her pregnant as soon as possible. So there’s even physical reasons that they thought they really needed to get young girls married and pregnant immediately. So you couldn’t stay a virgin.

SB: No, no, absolutely. That’s absolutely right. And that’s very true about the medical views at the time. Both physiologically and psychologically, it was thought that when they needed to get married and have children, that they might suffer a great deal of ill health that wasn’t achieved. But these three goddesses were allowed to get away with it!

AA: Yes, yes. Not realistic or attainable. Yeah, that is frustrating.

SB: No, not attainable, absolutely.

AA: And like you said with Athena and Artemis being these masculinized goddesses, you use the term “honorary males.” And I remember the myth of Athena’s birth. Wasn’t she birthed whole out of Zeus’s head? So they removed the maternity, there’s no mother involved, there’s no womb involved, and she’s just a creation of a masculine father. And then this very masculine person, which like you said, is not even attainable for women at all.

SB: No. And that thing of Athena not having a mother is mentioned, I don’t know if you know the trilogy The Oresteia by Aeschylus, but when Orestes goes on trial for murdering his mother, Athena sets up a court to try him for murder. And at the end of the trial, she gives her casting vote for his acquittal, and says, “I’m for the male in things, no mother gave me birth, so I support the male in everything.” Which is awful.

AA: Awful! What a betrayal. Oh, I would feel so hurt reading that, because you said these women had a spiritual relationship with this goddess. So to see a play, I don’t know if women went to plays but if you did–

SB: Well, we don’t know either. Yeah, that’s an interesting point, actually. You think, “God, what are the poor women sitting in the theater thinking about all this?” We don’t know whether they actually went. It’s one of those unknowable things. It’s one reason why I’d quite like to go back to ancient Greece to see if they went. But we still don’t know whether they went or not. It’s much debated, but I think we’ll never know.

AA: There’s a quote that I’d love you to read, Sue, on the bottom of page 43 that talks about boys’ relationships with their mothers. Could you read a bit of that paragraph?

SB: I should say this is a view expressed by another writer. It may well have been true, but I think you have to expand on it a bit. But anyway, this writer, who’s called Philip Slater, I’m paraphrasing him here: “Athenian boys who spent their formative years cooped up in the home with women who were frustrated and bitter would have been the object of disturbingly ambivalent feelings on the part of their mothers. Intense involvement springing from the need to find an outlet for repressed aspirations and sexual desires, coupled with tremendous hostility inspired by the knowledge that their sons would grow up into oppressive Athenian men, hence the Athenian male’s fear of sexually active women, and hence the violent mothers of Athenian myth and tragedy.”

AA: I guess that is a bit speculative, but it sure makes sense to me.

SB: I’ve read accounts of boys in the United States, going back to the 19th century, where these boys were brought up by Black nursemaids and that they would develop close relationships with these women. And then when they got older, they were taught to despise the people who had brought them up, and the kind of ambivalent feelings this would create. And you could imagine, obviously Athenian mothers were not Black slaves, they were free white women, but you can imagine something similar going on. That Athenian boys, let’s say Athenian boys brought up by their mothers in the home with them until they were seven and started to go out to school. And then when they go out into the wider world, they learn that these women are of no account whatsoever. And in them it must create very ambivalent feelings.

AA: One thing that really struck me about that passage was that it felt so familiar. I grew up in a very patriarchal religious context and I witnessed mothers who really, really loved their sons, but there was a lot of ambivalence and that feeling of jealousy and what you read, the hostility. And that comes from repressed aspirations and repressed desires, and it would truly create in these mothers a kind of mental unwellness that then the kids would think, “Oh, my mom is crazy.” Because the mom was not well, honestly, because she was so repressed, and it really poisoned the relationship for both people.

SB: Is that similar to the households that you’re thinking of in your childhood?

AA: Yes.

SB: Oh gosh, that is interesting.

when they go out into the wider world, they learn that these women are of no account whatsoever

AA: I think that’s maybe that’s why it resonated. Well, the next topic that I wanted to talk about, again this is quite familiar for people who studied this in school, are the Homeric stories. So The Iliad and The Odyssey. And I wondered if you could talk about two pairings of women. First, Helen and Briseis, and then the second is Circe and Calypso.

SB: The whole story of The Iliad revolves around Briseis, really, although she’s a minor character. Briseis had been the daughter of a minor king somewhere in the territory around Troy, and the city where she lived had been sacked by the Greeks. And Achilles had taken Briseis as his concubine, so she’s a prisoner of war. She was a high class woman, now she’s his slave and his bedmate. And Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek forces, says, “I’m going to have Briseis.” And that’s the reason why Achilles is furious. And the whole of The Iliad really is about Achilles withdrawing his support from the Greeks. He refuses to fight for the Greeks because he’s so annoyed about this. The anger, the wrath of Achilles. And Briseis is passed backwards and forwards. In the end, Agamemnon has to agree to return Briseis to Achilles. There’s a lot of interplay around her return, but she does eventually go back. And so she is passed backwards and forwards. She’s a sign of status, she’s a commodity for them.

She never really appears as a character in The Iliad except for this one occasion when she’s returned to Achilles, she sees that Achilles’s best friend, Patroclus, has been killed, and that’s the reason why he’s willing to fight again, really. But Briseis sees the body of Patroclus and she weeps and she says, “He was always kind to me.” And that’s a very moving scene. So she appears as a personality then, but otherwise she is just a commodity. And Helen is… Oh gosh. Helen is the reason why the war started. Or, not the reason necessarily, but she is a guest in Sparta, a guest of King Menelaus. He and Helen had eloped, gone back to Troy, and that was why the Trojan War started. This is all a myth, I have to say. It’s not necessarily true. But Helen is interesting as a character in The Iliad. Sometimes she’s blamed for the war as though she was the problem. Sometimes she’s made to blame herself, that she was the cause of the war. But she is also represented as a victim. So it’s very hard to know how to judge Helen. She’s a very intriguing character. She hasn’t got a huge role, but she’s clearly very important to the story.

AA: Because she’s valuable to the men, like you said about Briseis, she’s just a commodity, right?

SB: She is. Yes, absolutely. She is a commodity. And at the end of the war, I always hate this, she goes back. Menelaus takes her back and she has to settle down back in Greece after 10 years of fighting. She’s expected to become a kind of conventional wife and mother again. It’s really very strange.

AA: For sure. Okay, let’s see. Shall we talk about Circe and Calypso briefly too?

SB: Yes, one of the things about women in Homer’s poem The Odyssey is that they’re quite often monsters. And it is significant that an awful lot of monsters in Greek myth are female. Not all of them, but a lot of them are. So Odysseus is delayed by these physical monstrous females, these physical obstacles. But he’s also delayed by women who just invite him into bed, really. And am I right in remembering, is it seven years that he stays with Calypso? Which is an awful long time to be held prisoner by a woman. But he claims that he couldn’t get away from her.

And Circe, who’s an enchantress, a really fascinating character, is a woman capable of turning men into swine. And that seems to be very symbolic, that she makes men bestial. So she brings out the worst qualities of men and controls them. But he manages to turn the tables on Circe. Odysseus manages to avoid Circe’s wiles. His men get made into pigs, but he is given an antidote so that he won’t succumb to her magic potions, and then he gets control over her and dominates her sexually.

AA: Yeah, it’s really interesting to think about what anxieties men felt about women, right? About keeping them from their tasks or their potential and not letting them seduce you.

SB: Absolutely. It is amazing. And these stories go on, of course. The one about Calypso– and it’s the same with the sirens, they’re female as well and they can lure him onto the rocks. And it’s always the story. You still read so many novels written by men about men who just can’t achieve their potential because they’re held back by women. There was a famous saying by an English critic of the 1930s called Cyril Connolly, who talked about “the pram in the hall.” Once there was a pram in the hall, you could say goodbye to being an artist. So it’s always women who hold you back.

AA: Yes. Never mind your role in creating the baby that needed that pram, right?

SB: Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

AA: Okay. Let’s talk about Greek society. The fundamental building block of Greek society was the home, the oikos, right? Can you talk about how ancient Greek families were structured? And specifically, I’d love you to talk a bit about bride wealth. That was a really interesting part of the book for me.

SB: We’re talking mainly about Athens here, taking Athens as an example. Something that happens in the course of, let’s say, this is in what we call the Archaic period, so before the Classical period, it’s 700s/600s BC. Athens is slowly becoming democratic, Athens and other city states as well, and previously they have been ruled first of all by kings, but that was a long way in the past, and then by clans of aristocrats. So rather like Britain in the 18th century, aristocratic families were extremely powerful. And then we gradually got democratic institutions created. Something a bit similar in Greek city states is that you’ve got more democratic institutions gradually, very gradually created. And that process means that aristocrats are losing their power.

And the oikos, the household, becomes really the linchpin of Athenian society. And the ability of that oikos to support itself is really important. And that means it’s got to have a plot of land to live off. And the inheritance of that land, passing that land on from one generation to the next, is really crucial. And that’s where women are important. You need women, obviously, to reproduce the household, but it’s also very important to have control of their sexuality, and this is done increasingly by a number of laws. And it isn’t just a question that you’re trying to control women, you’re also trying to make sure that other men don’t have sex with your wife, basically. And adultery, in the Athenian context, means having sex with an Athenian woman that you’re not married to, basically. And it’s a criminal offense to have sex with another man’s wife, another man’s daughter, a widowed mother, anyone. It’s a criminal offense. But you can have lots and lots of sex with other people: non-Athenian women, slaves, that’s not a problem. You can have sex with who you like, but you mustn’t have sex with Athenian women. And this seems to protect the oikos and make sure that you’re not bringing up other men’s children. And it’s regulated quite strictly. It’s very difficult to say whether people were having it off all the time, women and men, it’s impossible for us to know, really. But they were certainly trying to regulate the family in such a way that transmission of land from one generation to the next was accomplished.

So the oikos is not exactly a nuclear family, but it consists of husband, wife, and children. When the male children are married, the wife might come to live in the family. Similarly, the husband and wife might have a widowed mother living with them. But it’s quite a small unit. It’s not a vast extended family. On the face of it, women were not supposed to leave the home very much. And yet, there is evidence here and there that working class women, to use that expression, in particular would have to leave the home for all kinds of things. Those women who worked in the markets, women who were employed as nurses. And, I mean, some of that work was done by slaves or foreigners, but they might well be poor, free Athenian women as well. So we know of all kinds of reasons why some women would have left the home, but the ideal was still increasingly that women should stay in the home. It’s not so much seclusion for women as segregation.

One very good reason why they went out was for religious worship. Women were very important in religion. But they were expected to keep a distance from men. I think that’s why I say at some point it would appear that democracy is not all that good for women. Going back 200 years or so, going back, let’s say, to the time of Homer, around about 800 BC, aristocratic women had lots of power and lots of freedom. And increasingly, as democracy is established in Athens, it seems women are increasingly confined. I think something similar is sometimes said about the French Revolution, actually. That it wasn’t necessarily all that good for women. The creation of the bourgeois family was not necessarily a good thing. But you have to bear in mind that when you talk about women who had historically once been powerful, they have been aristocrats. They’re like any aristocrat. They have lived by different rules, really.

AA: You write that as the polis emerged and became more important, women’s status declined. And there’s this quote that you had written that said: “Once she had given birth to the requisite male child, her usefulness was over and she was regarded as a parasite.”

SB: I think that’s a bit strong, really. Isn’t it? I might want to backtrack for a bit.

AA: All right, go right ahead! Let’s talk about the polis a little bit. Why was it that women’s status declined as the polis emerged?

SL: Because it was, again I’m talking about Athens here, the polis revolved around democratic institutions. In Athens, the democratic assembly, which all adult males of citizen class were allowed to attend. The assembly plus the executive council, which organized the business for the assembly, were all male. Of course, they were all male. And when aristocratic clans had been important, women had a certain amount of power. Now, nobody would have expected women to be included in these assemblies and executive councils, and they weren’t. So they are now completely excluded from power.

AA: And this is also the era when philosophy and mathematics and all of the intellectual pursuits were really booming, right?

SB: Absolutely booming, yeah.

AA: So it seems like a time when men were like, “What’s really the purpose of a woman but to keep the household running behind the scenes and produce male heirs?” All the higher level stuff, the intellectual, the cerebral, the masculine, could function just fine without women. Am I understanding that right?

SB: Yeah, I think that is by and large true. It’s a sad picture really, isn’t it?

AA: It is, yeah.

SB: But I think it is true. Apart from the area of religion where they are important, women have a very low profile in classical Athens.

AA: Let me ask a little bit about that too. So, women did have an important maybe ritual role in religion, but did men see it as really important, or was religion just a feminine space for them?

SB: No. That’s interesting, isn’t it? Because we now think of the church as being dominated by women. I mean, still ruled by men very often, but nearly everybody who goes to church is female. That’s what is the case here. Not that’s exaggerated a bit, but that’s not the case in Athens. Religion, Although there are, by the 5th century, the 400s BCE, the great period of philosophy and tragedy and so on, some people are beginning to question religion and the gods are questioned, you know, “How can you possibly accept a group of gods who behave like the Greek gods behave?” But even so, most people are conventionally religious, and religion is important to them. And I think that goes for men and women. And so the rituals which women performed were seen as very important. And Athens is a good example because Athena was their patron goddess, and she was served by priestesses. They have what you might construe as quite a powerful position behind the scenes, just on the level of religion. It’s not just a women’s thing, not by any means, actually.

One thing I would add about women’s rituals is that there were religious festivals which were exclusive to women. And one of them was the Thesmophoria, which was a festival devoted to Demeter and her daughter Persephone. And celebrating, amongst other things, the fact that Persephone was reunited with her mother having spent time as the bride of Hades. She was allowed to re-emerge for part of the year and be reunited with her mother. And at that point, the crops would grow again when Persephone annually came up out of the earth, et cetera, et cetera. The Thesmophoria celebrated that set of myths and it was exclusive to women. And that, just going back to one of your earlier questions, that’s an area where men were excluded. They couldn’t attend the Thesmophoria. So on one level, gosh yes, it’s really important for the fertility and prosperity of the city, it’s really important that women should have that role, but it also makes them very suspicious. They don’t know what those women get up to while they’re celebrating this all-women festival.

AA: Correct me if I’m wrong, but isn’t that a theory about where drama and theatre even came from in the first place? Was it women in the forest celebrating these Dionysian cults?

SB: Yeah, absolutely. Yes, indeed. It is one of the theories, one of the many theories, I have to say, but yes, it is.

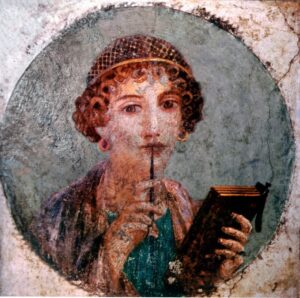

AA: Let’s talk about maybe one or two more things from the book. I’m tempted to go into every single chapter you wrote. But one thing that I was so excited to see was a chapter on Sappho, because that’s someone that I’ve always wanted to learn more about and never had. And so I was grateful that you dedicated a whole chapter to Sappho. Could you tell us about her and her significance?

SB: She’s significant now because she’s one of the few – we have fragments of other women poets, she’s not the only one – but she’s the only one whose work we have in any quantity. Obviously she wasn’t living in mainland Greece, she was living in Lesbos, in the eastern part of the Greek world on the other side of the Aegean. She wrote what on the face of it are passionate love poems addressed to women. And I think nobody now would really question that she was expressing desire for women in these poems. People have found all kinds of excuses in the past for this. One view was that these poets didn’t just write these poems for themselves, they wrote them to be performed by other people as well. They had to make a living somehow. So one theory about Sappho was that she was putting all these desires for women into the mouth of a male singer. So she’d written it for a male to sing. I don’t think anybody really believes that now. But that was an idea at one time.

But the question arises, as it always does with literature, to what extent are the feelings being described the feelings that you can attribute to the author? And you don’t know that, you never will know it. It’s always a question. But the feelings expressed in some of the poems are so powerful, and Sappho wrote them, that she must have known what those feelings were like. And it does appear from what she writes, and what other people write about her later on, that she was part of a group of young women living on the island of Lesbos who devoted themselves to poetry and music. They were like a sisterhood. And this is not a thing you can ever imagine happening in Athens. I mean, it’s quite an early period in Greek history and it’s in a different place, it’s in Lesbos. And it throws a completely different light on the way that women were organized and the way they lived their lives. It is very interesting.

AA: Was she widely read and was she respected by men as a poet at the time?

SB: She was.

AA: I thought so.

SB: Yeah. And later on as well. Quite a few people called her the tenth muse. There were traditionally nine muses and people talked about her as the tenth. But yeah, she was widely read. This raises the whole question, which is quite a fraught question, as to the acceptability of homosexual or homoerotic relations. Obviously, in some parts of Greece at some time, including 5th century Athens, though the golden age, relationships between older men and younger boys, we have to call them, were seen as perfectly acceptable. Probably there were relationships where there wasn’t that generation gap. And the male relationships are well documented. We don’t know so much because nobody bothers telling us about homoerotic relationships between women. But I think you would have to say back in Lesbos, in Sappho’s time, it probably was widely accepted.

nobody bothers telling us about homoerotic relationships between women

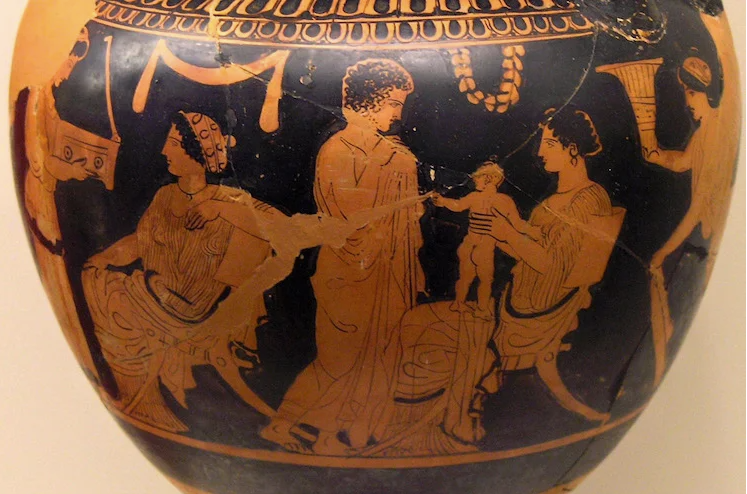

AA: Thank you. Well, there are some illustrations in the book of vases that do.

SB: Yes, there are. Absolutely. Some people were doing it because we’ve got pictures. And those were Athenian vases. So yeah, some women were doing it.

AA: Well, that’s fabulous. That was one of the most interesting parts to me. The phrase that comes to mind is “the exception proves the rule,” right? That there was one woman who was accepted as a great poet and writer and she was smart enough to produce great literature, but the fact that we know just that one woman’s name… It’s really a shame, but I guess, is it possible that there could have been more that just didn’t make it through?

SB: We know the names of a number of other women poets actually, and we do have fragments from others. Sappho was without a doubt the most famous, but there were others.

AA: That’s good.

SB: One of the debates about women, I mean, this is not to do with poetry, but one is whether they were allowed to paint pottery. There were two stages in the making of Athenian pots: one was actually making the pot and the other one was painting on it. There’s one scene on a pot which shows a woman, she is in the corner crouching down, but she is painting a pot. So, maybe they had women painters as well.

AA: Oh, that’s lovely. And she painted herself in to show that she was the one doing it! Oh, that’s amazing.

SB: That in itself is interesting because I used to specialize in vase paintings, and from about 450 BCE onwards in Athens, there are an awful lot of domestic scenes painted on pots featuring women. And why did they suddenly become so interested in what’s going on in the home? One theory is that there were more women painters being employed. I mean, that’s not to say that these are free Athenian women. If there were women painters, they were very likely slaves, or the other category of people in Athens. There are free people, there are slaves, and there are what you might call “resident aliens”. And quite a lot of this is a bit of an exaggeration, but people would emigrate to Athens because it was very rich and they knew they could get work there.

AA: Oh. So nothing’s changed.

SB: Yeah, no, exactly. It’s like London. We have always relied on people coming here because we’re quite a rich country, and the same with the U.S. as well.

AA: Yeah, interesting. One last topic is the comparison between Athenian women and Spartan women. What was daily life like for those two groups of women? Quite different, I think.

SB: Quite different. And this is what makes you kind of stop and say, “Oh, yes, but most of our source evidence is about Athens and things would have been very different in Sparta.” Though I think the most important thing that’s going on in Sparta… In Athens, women could not inherit. When the land passed from one generation to the other, when a father died, the land was divided between his sons and the women didn’t get any portion of this. She got a dowry instead. In Sparta, women could inherit. And notoriously, it seems that by the 300s women owned a very large amount of land. I think somebody tells us that about two fifths of the land was owned by women, who were obviously rich.

AA: Wow. Amazing.

SB: And Sparta was having problems by this time because its population was declining and there were all kinds of things going on, which brought it to its knees, really. And some people blame that on the fact that women were allowed to inherit land. But anyway, quite apart from their ability to inherit property, they had more freedom. That’s clear. They received physical training. So, like the boys, they went out, they ran, they did boxing, and threw the javelin, and so on and so forth. And most of our sources who are not Spartan, quite a few of them are Athenian, well, Athenian writers think this is very licentious. But what they say about it, and it may well be true, is that Sparta wanted its women to be physically strong so that they would give birth to strong warriors. And there’s no doubt that allowing women to have physical exercise is going to make them into stronger mothers, apart from anything else, apart from the fact that they might have enjoyed it. They got married later as well, that’s interesting. Aristotle tells us that Athenian women seem to have gotten married very soon after puberty, so about fourteen or fifteen. Spartan women didn’t get married until they were eighteen, and that was late by Greek standards. Aristotle says they’re much more capable of bearing healthy children if you don’t make them pregnant immediately after puberty, which seems sensible.

AA: Yes, definitely. Like we said before, contrary to what was kind of an accepted medical belief about needing to get a girl pregnant right away.

SB: Yeah. The Spartans did not live by those rules. Absolutely. They thought for whatever reason that you should wait. And I think Spartan women, quite apart from being allowed to go out and throw javelins and things, were notorious for being very loud, outspoken, and bossy. The complicated thing for us is a lot of this outspokenness and vigor, and dominance of the home, they were dominant in the home because their husbands, until the age of thirty, Spartan men were living in a military camp. They never went home at all, or hardly at all. So women were definitely in control at home in Sparta, not in Athens. So, yes, they’re bound to be outspoken. But a lot of this seems to have been harnessed by the militaristic state. So that these women in the stories, we’re told a militaristic ideology. There are lots of sayings attributed to Spartan women, but the most famous one is probably when she says goodbye to her son. He’s going off to war and she says, “Come back either with your shield or upon it,” which means either fight well and don’t get captured, or come back dead. That’s the only choice, really. No room for people who flee. There are stories, not quite like that, about the First World War here, probably in the States as well, about people who deserted because they were terrified and, you know, just going crazy. And the reception when they got home was appalling. They were just shunned. And only recently have quite a few of them been pardoned. It’s terrible. Spartan women seem to be harnessed for that military machine. So in some ways great lives, in other respects you wouldn’t envy them. If you were to ask me, I think being a high class prostitute in Athens was probably the best way of being a woman.

being a high class prostitute in Athens was probably the best way of being a woman.

AA: Really? Go into that a bit.

SB: Well, I mean, most prostitutes were slaves or foreigners and didn’t have a very nice time at all. But there were some like Aspasia, who was the mistress of Pericles, one of the top generals in Athens. She was born in Miletus in what is now Turkey, so she was a “resident alien” in Athens. But she and other women like her, she was by no means the only one, were like courtesans and they made a lot of money and had very cultured lives by becoming the mistresses of famous men. And there are quite a lot of stories. Aspasia is supposed to have talked to Socrates. They used to have chats about philosophy and so on and so forth.

AA: Wow. So if you were lucky enough to be selected by a powerful man to be his private prostitute, I guess, you could eke out a pretty good life.

SB: Yeah, it’s like that. Absolutely. Not much of a fate, really.

AA: I mean, it just goes to show the difference between the structure of a society and then what individual lives look like. There’s a lot of variety, but the structure just seems so very patriarchal from top to bottom and throughout all of their eras.

SB: No, it is. It is patriarchal. There is absolutely no doubt about that.

AA: Well, is there anything else you’d like to add at the end? This has been the most delightful discussion, but is there any takeaway, or I guess not a takeaway with your own book, but is there anything you’d like to add at the end?

SB: I suppose I would just say that I became a feminist in the 1970s, when examining women’s oppression was a very big part of being a feminist. And since then, of course, a different kind of feminism has emerged where instead of looking at women as victims, we explore the strengths and the achievements of women. And I wish it were more possible to do that in Athens, or Greece, I should say. You can do it with people like Sappho. And you can celebrate women, there’s no doubt that possibility is there. But it is nearly always through a male lens that you’re doing it. So if you look at the women in Aristophanes’ comedies like Lysistrata, they’re fabulous women, and let’s hope those women existed, but it’s really hard for us to know whether they did or whether it’s just a male fantasy. Oh, let’s say they did exist. They must have done, mustn’t they?

AA: Haha! Well, I feel like that really came through in your book. I felt like you did talk about the structures that disadvantaged women so much, and that’s important to know, but you also did represent so many strong women and it was so nuanced in your approach. I really enjoyed it. And there were so many fabulous stories, too. So many interesting and wonderful stories. That really came through in your book. And again, I highly recommend it to listeners. It’s called Women in Ancient Greece. And Dr. Sue Blundell, thank you so much for being here and discussing this with me today. I enjoyed it so much.

SB: You’re very welcome. I enjoyed it enormously too. It’s good to meet you at last, Amy.

AA: You too. Thank you, Sue.

she was part of a group of young women…who devoted themselves to poetry and music

They were like a sisterhood.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!