“Authority is our daughter’s birthright”

As this second season of the podcast approaches a close, we want to spend a little more time discussing the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints—not to dwell in the pain which the Church’s patriarchy has caused, but rather to imagine some possible steps forward. To start envisioning a new Church for the future, a Church with regard, respect, and opportunity for all of its members, and to explore some of the potential steps that will lead us there.

To help us illuminate these paths forward, it’s my delight that in this episode we’re joined by Kajsa Berlin-Kaufusi who shares a stunning vision for the Church’s feminist future.

Our Guest

Kajsa Berlin-Kaufusi

Kajsa Berlin-Kaufusi (she/her) is, what you might call in French, a “flaneuse”—that is, a woman who enjoys the process of wandering and exploring, whether it be a local bookstore or a new international destination. She completed her BA at Brigham Young University, followed by an MA in Biblical Studies from Regent University. Her research focuses on feminist/progressive theologies, early Christianity, Medieval Judeo-Islamic philosophy, world religions, and women’s narratives of the religious experience. Today, Kajsa is devoting her time to writing, with a book forthcoming, and spending time with her family. She is also the proud owner of a Great Dane named Freja, who is one of the loves of her life.

The Essay

A few years back, I attended a Priesthood ordination for a nephew of mine. As a Latter-day Saint, this is a very big thing in our culture; Priesthood ordination prepares our young men to eventually become leaders in the church, holding keys of authority and administration. The room was packed with supportive uncles, male cousins, and grandfathers who surrounded this young man in the act of ordaining him to a Priesthood office. The scene was beautifully powerful, and yet, as I was scrolling through the photos of the event, looking at the dozen or so men surrounding my nephew in the photos, the reality stared me starkly in the face that none of my nieces who had attended in support of their cousin/brother would ever experience such a matriarchal presence in recognition and confirmation of their spiritual progression. Such an occasion simply doesn’t exist in our church. Had any of the men present made that connection as they gazed in the vibrant and intelligent eyes of their daughters–of my nieces? Were they aware of this imbalance in church culture, and if they were, did they care?

I had forgotten the bittersweet feelings of that memory until, recently, another nephew was advanced to the Priesthood and the same ceremonial rituals occurred. Once again, the women took a backseat as “the brethren” celebrated this young man. My mother’s heart felt heavy as I thought, “what message is this sending to my nieces? What message will this send to my daughter when she is old enough to understand that this world of celebratory Priesthood progress is exclusive, and she will never be a part of it?”

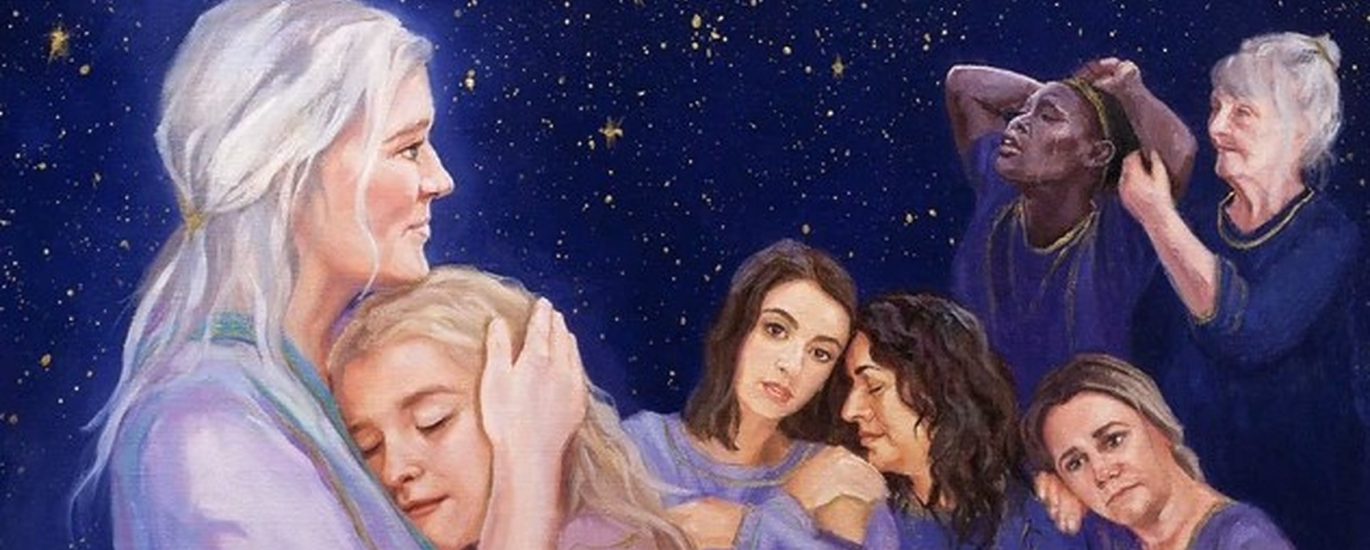

This experience and countless others have solidified, for me as a congregant, the reality that LDS orthopraxy is void of the female presence. If indeed our doctrine proclaims the existence of God the mother, why is it that LDS women are clawing at fragments of doctrine surrounding her, when surely the remaining corpus must exist? In a recent art exhibit titled Reflections on A Mother in Heaven, dozens of artworks by Mormon women displayed individual portrayals of the idea and existence of Heavenly Mother. As I wandered through the pieces with like-minded women, eyes gleaming as they toured the works, it stood out to me how many of the pieces were intentionally created in abstract. Blurs of an obviously feminine figure, but with no details, painted onto canvases in soft, heavenly colors. One specific work stood out in my mind, and I found myself coming back to it, staring. Reflective of the Rorschach approach, three framed ink blots stood in front of me, each with the words, “Oh God, where is she?” written in the middle of the ink abstracts.

Our girls must see themselves reflected in church leadership, in general conference addresses, in preparing and performing ordinances, in prayer language, and in the celebrated ritual surrounding rites of passage that we ceremoniously perform for our boys and men. Likewise, our boys need to see our girls in these capacities, standing in their deserved space of recognition and influence. This needed balancing of church structure would set our youth to a healthy path of interdependence, illuminating in ways not yet tapped the power of men and women working together.

As a woman raised in Mormonism, my soul has been frequently vexed by storms of longing, awareness, and conflict as I’ve grappled with my relationship to LDS theology, feminist awakenings, and my responsibility as a woman, as a daughter, and as a mother. I am not alone in these storms. My inbox is frequented by messages from women who share with me the expansive awakening of their own selves and their potential, of their connection to the divine, and of a raw and hungry desire, simply put, that their daughters be given “more” than what was offered to them as a girl. These emails are full of emotion and tangible energy, and I do not doubt that this awakening is happening globally, both within Mormonism and outside of it.

The women who share these experiences also express fear–fear that this energy, for them, has no sanctioned place to exist. Fear that talking about these desires will “out” them from the circle of orthodoxy, placing them within apostate territory, identifying themselves as those who “rehearse their doubts.”[1] Yet, for all these women, it seems that silence is no longer an option—that the energy burning within them must give birth to itself, to the creation of a better world, lest it be contained and become a destructive force. The heat of this energy pushes these women to MOVE–and how they move, initially, is through their words; they refuse to be silent any longer, and as we know, in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. Do our words, as women, have the potential to come straight from the divine, conceiving of a better way, paving the path for tangible changes? Our very histories whisper, encouragingly, “yes!”

I suggest that in order for this to occur, a tangible change that could act as a catalyst to this “better way” is Priesthood expansion. Priesthood expansion is the expanding of priesthood responsibilities to women with accompanying titles that are unique to women but whose purpose holds the same roles and responsibilities as the corresponding male titles. Ask any Latter-day Saint what the Priesthood is, and they might say, “the Priesthood is the gift and power of God given to men to act in his name,” or possibly, “Priesthood is God’s power and authority. Any member of the church, male or female, can minister through faith in God’s Priesthood, but only males are ordained to offices that hold authority of the Priesthood with specific functions and responsibilities, including giving blessings of healing and comfort, baptizing, blessing and administering the sacrament, and if called, bestowing Patriarchal blessings to those who seek it.”

…this awakening is happening globally, both within Mormonism and outside of it

Having heard that, it should be clear to the listener that Mormon culture, theology, and administration is overwhelmingly male. Within the recent memory of many LDS, the “Ordain Women ” movement and its subsequent excommunications and resignations lives on with associations of enigma, anathema, respect, scandal, and dashed hopes. Formally organized on March 17th, 2003 by Human Rights attorney Kate Kelly, Ordain Women vocally advocated for women’s ordination to Priesthood offices within the LDS church. Through online social media campaigns, organized marches, and physical presences at the male-only Priesthood session of the church’s semi-annual General Conference, Kelly’s boldness created public space for discussion on something that was previously only whispered about behind closed doors, for fear of church discipline. Indeed, formal disciplinary action didn’t escape Kelly, who was excommunicated from the LDS church on June 23th, 2014 on the grounds of apostasy and public advocacy for action contrary to church teachings.

Wise to the expansive nuance that the movement represented, and aware of the diversity of opinions on the matter among LDS women, when asked to comment on Ordain Women, former BYU Ancient Scripture professor Dr. Camille Fronk Olson stated, “I would say Kate Kelly and Ordain Women, the questions they have asked, the courage they have exhibited, the discomfort they have created, have all contributed to greater discussion–People now realize there are some women who are hurting, and men who are hurting–I would say this has contributed tremendously.”[2] Realistically, this expansion could take place in three specific areas: 1) correlated and consistent gender-inclusive language 2) inclusion of women on High Councils and Disciplinary Courts and lastly, 3) women operating in official capacity during ordinances, including administration of the sacrament, baptism, and blessings of healing and comfort. In her influential piece “After the Death of God the Father: Women’s Liberation and the Transformation of Christian Consciousness”, Mary Daly discusses with her reader the phases of the Women’s Liberation movement and then suggests, “what I am saying is that Phase One of critical research and writing in the movement has opened the way for the logical next step in creative thinking. We now have to ask how the women’s revolution can and should change our whole vision of reality.”[3] In relation to Mormon women and their push for equality, inclusion, and representation, one can clearly see that this statement also applies to our unique branch of the Judeo-Christian tradition, with the first fruits of progress paved by women such as Eliza R. Snow, Martha Hughes Cannon, Juanita Brooks, Fawn Brodie, Maxine Hanks, Lavinia Fielding Anderson, Carol Pierson, Kate Kelly, Janna Reiss, and many more unmentioned.

The pattern of feminist change within religious structure laid out by Daly in her essay is one that reflects itself on the contemporary Mormon experience. Extensive discussion, written pieces, and agitation have occurred on the subject of patriarchal deconstruction. The next step that Daly lays out, and that Mormon society finds itself swimming in, are the tides of change that come with tangible action. Consider that “as the women’s revolution begins to have its effect upon the fabric of society, transitioning it from patriarchy into something that never existed before–into a diarchal situation that is radically new–it will, I believe, become the greatest single potential challenge to Christianity to rid itself of its oppressive tendencies or go out of business.”[4] A review of Jana Reiss’s The Next Mormons makes clear that the younger generation of Mormons are passionate about reform and see it as essential for their continued interaction with the church. In light of the Ordain Women fallout, Reiss’ work and the plunging global statistics on church membership, as well as the growing number of social media groups providing safe spaces for women to express their angst over women’s spaces and experiences in the church, the need to move theology forward, specifically, expanding our priesthood, is evident.

The first suggestion I make for priesthood expansion to occur is the execution of a correlated and consistently used gender-inclusive language. Growing up, whenever the phrase “the brethren” was used to insinuate final authority, my mother would snarkily whisper under her breath, “what about the sistren!?” I found this covert rebellion funny, but I also found myself somewhat nervous of the humor, certain that God was frowning at my mother and I as we giggled, making light of the sacred. Then of course there was the occasional actual frowning coming from my good but sometimes over-conservative father, his blue eyes bright under his furrowed and focused brow.

The snide sentiments of my mother were also sincere, betraying tangible undertones of a very real problem. The reality of the Latter-day Saint experience is that the constant use of male gendered language in relation to God, church authority, and as found in scriptural passages smacks in the face of the idea of “progressing” our theology, or, to use a more recognizable phrase, “the ongoing restoration.” It has been suggested that if a defined theology of the “mother” God and her priesthood were to be brought about, it may fall on the shoulders of women to produce that theology.[5]As a Mormon woman in academia, I know well the reality of the seeming impossibility of women progressing the theology of the mother God—at least, within orthodox circles. One need only to reflect on the recent buzz surrounding Fiona Givens’ early departure from the Maxwell Institute following her suggestion that the Holy Ghost may in fact be God the Mother to understand the volatile and “tread lightly” contemporary attitude surrounding the idea and identity of a Heavenly Mother.[6] Givens, formerly employed at BYU’s Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, commented during a recent address that took place among single adult church members in Harlem, NY, that in her research she found numerous examples throughout the Biblical text supporting the idea of a “pillar of light” being connected to the presence of a female deity; as described in Joseph Smith’s first vision account, a “pillar of light” descended gradually over him, in which Smith claims to have seen God the Father and Jesus Christ. According to Givens, it wouldn’t be unfathomable to claim that the pillar of light attending the visitation was, in fact, Heavenly Mother.[7] Due to the First Vision, occurring in 1820, being a founding event Mormon History, to suggest that the Goddess was also present during that experience, no doubt, ruffled some feathers.

Eliza R. Snow is credited for formally penning creative content that reflects a mother in heaven, and yet, beyond formally declaring that “she” exists, LDS theology is void of any kind of tangible or attributed description from which one could potentially conceive of her. Instead of feeling peace about the doctrine of a Mother God, those who hunger to know more are often left feeling frustrated, silenced, patronized, and gaslighted.

Perhaps you’ve heard the quote, “before I was a wife and a mother, I was myself.” Author Sue Monk Kidd points out that many balk at the idea of a Goddess, finding the term “mother God” or “Heavenly Mother” more palatable. This, I suggest, is because in our Judeo-Christian paradigm, we are incredibly uncomfortable associating a woman with her own identity. Rather, traditionally, she has always been who she is “in relation to” a male figure. Mother, daughter, wife–all approved titles with appropriate male connections. Can you recall the last time you heard the title Goddess uttered in an LDS context? The idea of the Goddess implies that she is divine in and through herself. That her divinity exists independent of a male counterpart; she is her own authority–a powerful, independent agent. While I embrace the idea of a “Divine Mother,” in order for her potency to catch hold in society, and more specifically, in the Latter-day Saint paradigm, we must allow her to embody her own space, separate from “the Father God.” Additionally, it must follow that her identity be referred to in our regular speech. Words matter. Traditional scriptural narrative surrounding God allows both identities–one of autonomy, and one that is relational. So too must we allow such space for the Goddess.

Interestingly enough, careful reading of the Biblical text reflects not only that the title “God” is gender neutral, but it is also plural. Additionally, the Old Testament is full of feminine language used to describe the attributes of God, and in Rabbinical literature, the very presence and glory of God, “Shekinah” in Hebrew, is a female noun. One particular Hebrew name for God, “El Shaddai,” has a strong linguistic connection to breasts–thus, it is not surprising that Isaiah used such poetic language relating to lactation when describing God’s commitment to creation, as found in Isaiah 49:15.

It must be acknowledged that the LDS church has made progress in using gender inclusive phrases such as “our Heavenly Parents,” or specifically referring to Heavenly Mother herself. In October of 2019, President Bonnie D. Cordon of the general Young Women’s auxiliary announced a new Young Women’s theme, specifically replacing the former wording of “We are daughters of our Heavenly Father, who loves us, and we love him” to the updated “I am a beloved daughter of Heavenly Parents, with a divine nature and eternal destiny.” Additionally, the young men’s theme was also updated, but with an exclusive relationship to God the Father, focusing on the father/son dynamic. Two thoughts came to me when this occurred–1) does church leadership not think it important or of value for the young men of this organization to identify with a Heavenly Mother? and 2) Should the Young Women’s theme focus solely on the mother/daughter dynamic, how would the church body respond? If LDS theology affirms the existence of the mother, it is high time we give her a consistent place in our church-speak.

My second suggestion is to implement the inclusion of women on High Councils and Disciplinary Courts. In the LDS church, a High Council is a group of men holding the Priesthood office of Elder, and thus typically experienced with ministerial responsibilities, who are consulted on various issues occurring within their region, as well as being assigned to speak in local congregations and being present during a Disciplinary Court. A Disciplinary Court is held under the direction of Priesthood authorities when the orthodoxy and/or obedience of a church member has come into question. Members of the Disciplinary Council decide the fate of the congregant in question, prescribing penitent stipulations or, in extreme cases, disfellowshipping or excommunicating the person, thus stripping them of their membership privileges.

…her divinity exists independent of a male counterpart; she is her own authority – a powerful, independent agent

In her essay, Daly admits that the belief systems we have created for ourselves become “hardened and objectified, seeming to have an unchangeable independent existence—It resists social change which would rob it of its plausibility. Nevertheless, despite the vicious circle, change does occur in society, and ideologies die, though they die hard.”[8] In light of this perspective, one need only look briefly at LDS history to see shifts in what was once unacceptable space for women, specifically the workplace, academia, and some church councils, now being occupied by women and also celebrated, if perhaps through lip service only, by the very magisterium that at one time condemned women who dared cross those lines.

In regards to High Councils, it is a simple lateral solution to conceive that the council have women appointed to its numbers, specifically, women who have occupied formal ministerial positions, such as a position in the Relief Society presidency or Stake Relief Society presidencies. The Relief Society functions as the church’s women’s organization and is administered by a president and two councilors, overseeing the spiritual and physical needs of the sisters in their stewardship. Thus, to have a woman on the High Council who has served in ministry to the Relief Society would no doubt add depth and experience to the group.

Additionally, in the case of when Elders are called into the High Council and consequently appointed as High Priest, so should sisters who are called into the council without previous stake or ward level experience also be appointed the title of High Priestess. While the title of Priestess will no doubt cause many to balk, let us not forget that in the New Testament, we have the title of Prophetess given to Anna. Surely we can expand our nomenclature to include the title High Priestess, in light of the fact that according to Paul, we are all one in Christ Jesus, who is our great and final High Priest. This change to the system would not only improve the content and quality of discussions being held and feedback being given, but it would also increase the presence of women at the pulpit, as one of the responsibilities of those sitting on the High Council are speaking assignments throughout local congregations.

In light of Disciplinary Councils, also known as “Courts of Love,” the countless numbers of women’s narratives illustrating the trauma experienced by an all-male jury is substantial and inexcusable. In addition to the intimidating and biased environment presented by a male audience, when transgressions discussed push into the realm of chastity, the inappropriate nature of such a situation is glaring and inexcusable[9]. As a suggested remedy, an equal number of women and men should sit on all councils, whether the member in question be male or female.

Lastly, I suggest and advocate that women operate in official capacity during ordinances, including administration of the sacrament, baptism, and blessings of healing and comfort. This idea is hardly novel. Countless women have suggested this before, whether it’s a blanket call for ordaining women to the priesthood or creating lateral priesthood titles and terms for women which would allow them to act in official capacity within their congregations, enhancing the overall visual presence of women within the functions of structured worship. By official definition, Priesthood power is “ the power and authority that God gives to man to act in all things necessary for the salvation of God’s children.”[10] Given that definition and the church’s approach to the word “men”/”mankind” being inclusive of both men and women, it is evident that the current approach to keys and administration being solely male is a policy that has room to grow.

This may seem in direct contradiction to the words of President Dallin H. Oaks in a recent conference address where he stated, “only those who hold a priesthood office can officiate in a priesthood ordinance–even though these presiding authorities hold and exercise all of the keys delegated to men in this dispensation, they are not free to alter the divinely decreed pattern that only men will hold offices in the priesthood.”[11] This statement seems to clearly put the kibosh on women holding offices in the priesthood. I would like to push back on this statement by President Oaks, and provide an alternate possibility made available through an episode in Mormon History. A few years back, I publicly reflected on the reality that at the time, while only those appointed to a priesthood office could witness a baptism,[12]it seemed plausible that this be a responsibility that could be expanded to include women, given that Camilla Kimball, wife of then Prophet Spencer W. Kimball, had in fact performed the part of witness during a baptism that took place when the two were on assignment in India.[13] I of course got some expected pushback and was reminded by an online commenter that, “I think this could be a nice idea but I don’t see it happening, seeing as it takes an office of the Priesthood to carry out that function.” It was obvious that not everyone was seeing the loophole I was seeing; imagine my sense of irony when not quite one year later, the church announced its updated policy that any baptized member of the church, regardless of gender, could now act as a baptismal witness.

the countless numbers of women’s narratives illustrating the trauma experienced by an all-male jury is substantial and inexcusable

This update was celebrated but also left the unanswered question in its wake, “is priesthood authority ever actually required to perform a function or is it just our policy that dictates it so?” Indeed, if the definition of Priesthood is “the gift and power of God given to man to act in his name,” would not faith alone in that power make one worthy to administer it? Social media has allowed for open discussion of this hot topic, specifically addressed by the viral podcast, “At Last She Said It” in their episode “Where’s the Priesthood in That?”[14] During this discussion, the stories of numerous women were shared that illustrate the inconsistency of what and why priesthood authority is necessary for a certain activity.

This is but one of no doubt dozens of examples that could be used to illustrate that perhaps, just perhaps, it isn’t inconceivable to imagine young women passing and even blessing the sacrament. While Old Testament imagery of male-only Priests officiating over temple sacrifices seem to justify our current policy, the truth found in the Book of Mormon that “all are alike unto God,”(2 Nephi 26:33) combined with the New Testament truth that “there is neither male nor female…for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28), opens one’s mind to consider the possibilities. This is the approach taken by a variety of Protestant denominations who emphasize a “Priesthood of believers,” its power being manifest through the faith of the individual in Jesus Christ and his authority. Additionally, it should be noted that while not embracing the idea of a Priesthood of Believers, Catholics additionally allow any believer to perform the ordinance of baptism, should death be imminent.

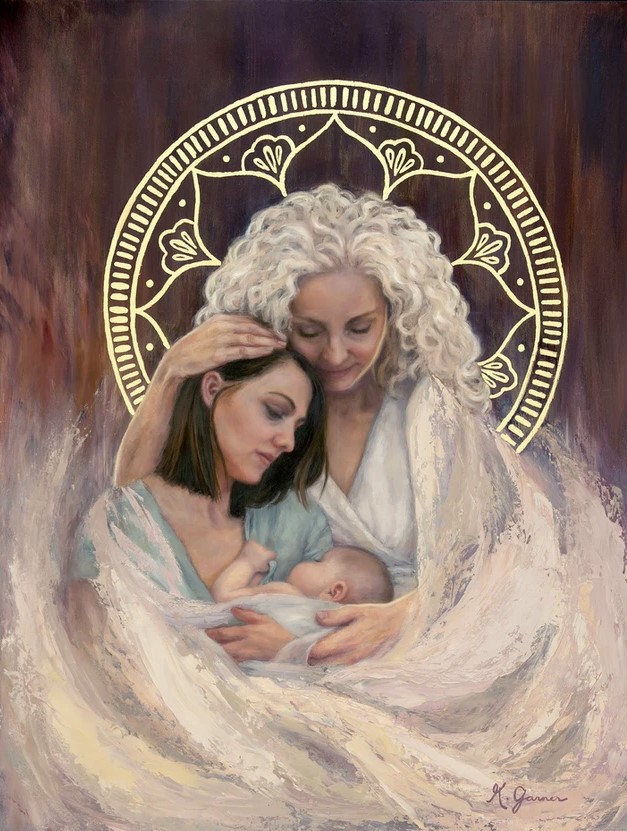

In addition to the blessing and administration of the sacrament, what about the act of blessing with the laying on of hands? Early Mormon history attests to the fact that women both anointed and blessed those who were afflicted, and our cousin fundamentalists denominations have maintained and refined that capacity into matriarchal blessings, given both to comfort, in preparation for childbirth, and to heal, being seen as a necessary administration throughout a woman’s life. In her article “The Order of Eve: a Matriarchal Priesthood,” Kyra Krakos combines both personal experience with her professional scientific background to illustrate Mormonism’s diverse usable histories in relation to women administering blessings, by virtue of their Matriarchal Priesthood line.[15] While discussing a sacred experience where she administers to her own mother a mother’s blessing, she recalls “As I spoke, I realized that it was a mother’s blessing, but also a Mother’s blessing. Just as you do not need to be a father to give a blessing on behalf of Heavenly Father, so it is with a Mother’s blessing. We are Their children, and our blessings are a chance to give voice to the blessings of our Heavenly Parents.”[16] She goes on to quote her own mother who wisely said, “Oh! Our priesthood didn’t need to be restored because it was never lost!” Krakos goes on to say, “Our matriarchal lines have never been broken. Mother to daughter, that unshuffled mitochondrial DNA handed down even when we weren’t aware of it. There is never a question of who the Mother is; she cannot be erased.”[17]

Having been raised from my youth and also trained academically in the scriptures, the reality that spiritual gifts are ours upon asking is a precious truth for all believers, though for many, an unknown reality. The gift of healing, specifically, is addressed in 1 Corinthians 12:9 and in its Greek form is actually plural, charismata iamaton, and is related to gifts of faith and miracles, which should come as no surprise. As a teen, I began to travel globally, and I remember feeling a sense of discomfort blended with awe when I would encounter indigenous traditions with their own way of doing things that were very different from my own society, and yet, seemingly, just as effective and just as real. Being immersed in the post-colonial, white tradition of being the “gazer,” as coined by Edward Said, I did plenty of gazing. Looking at other ways of doing things, judging them for what I perceived as childish, dark, supernatural, etc. All of these descriptions seemed appropriate because certainly, what I was seeing/hearing couldn’t actually be real, right?

Currently, the LDS church handbook casts suspicion on healing of a “miraculous nature,” unless it comes from a system that is our own, specifically, a male Priesthood holder. While I can appreciate the genuine concern to protect people from fraudulent practices, how do we ensure that the Priesthood holder we call upon to minister to us isn’t in fact acting fraudulently? In regards to the miraculous, isn’t that exactly the term we would use to describe a successful blessing of healing–miraculous? Additionally, the church handbook differentiates between a prayer of faith, which a woman may offer, and a priesthood blessing with the laying on of hands, by virtue of priesthood authority. The idea of “laying on of hands” is something that did not originate with Latter-day Saints. This is a global practice and can be seen used in various capacities of blessing, anointing, ordaining, comforting, etc. Indeed, is there anything more natural in ministry than to reach out and physically make contact with someone? Jesus himself modeled this many, many times. This act seems to harness the power of creation that is existent in each of us–perhaps we could call it the light of Christ–and is something that each of us utilize frequently whether we realize it or not.

Additionally, I have yet to have it explained to me what the difference is between a faithful prayer and a Priesthood blessing, which, given the church’s preference for one to call upon a Priesthood holder during times of distress, I can only assume is a push towards Patriarchal control of a very natural system that is meant to be administered organically, as prompted by the spirit, and not controlled through an ecclesiastic structure. As a graduate student, I had the unique opportunity to study with a group of mostly protestant students, who were either non-denominational, Baptist, or associated with some sort of charismatic sect such as 7th day Adventists, Pentecostal, etc. Needless to say, their worship styles were far more vivacious than what I was accustomed to–allowing outpourings of the spirit to be recognized with uplifted hands, enthusiastic affirmations of “amen!”, quiet and gentle spontaneous whispered prayers, etc.

When provided opportunities to worship together with my cohort, it took me a while to relax enough to rid myself of my self-conscious conservative “Mormon” manner and allow my body to react simultaneously with the acclimations of praise that came from within my soul. Had I been recorded during these church services, no doubt I would still have most likely been the most conservative person in the room, body-language wise, but after three years in that environment, I could comfortably raise my hands in praise, sway to the rhythm of a moving, contemporary worship song, and shout acclimations of praise when feeling so inspired. On one particular occasion, during a Spiritual Formations course, a classmate who was struggling in their personal life asked if the class would pray for them. The instructor, particularly in-tune with students’ needs as well as Christian psychology, reacted affirmingly and lovingly, encouraging the class to circle around this young woman and to “lay hands” upon her. I balked. I had never done this before. Immediately, my mind raced with the LDS association of “laying on of hands” in association with Priesthood authority–any yet, the spirit drew me forward out of love and concern for this fellow classmate.

My heart racing, I joined the class, though still somewhat timid and unsure of the orthodoxy of what I was doing. Encircling her, we stretched out our hands towards her, making a full connection between our bodies and hers, with my hands being on the shoulders of my classmates whose hands were on this young woman’s head. In this manner, one student offered up a prayer to Heavenly Father that he would see her need and pour out blessings upon her. After this student ended his prayer, another student picked up, offering words of comfort and power, laced with scripture and sincerity, after which, another student followed in offering a blessing of comfort, reminding this woman of the promises God has made her. After this genuine and spontaneous act of blessing occurred, we all hugged, some with tears running down their faces, allowing the spirit within the room to engulf us all, for all had participated, and all were edified.

In conclusion, as LDS theology continues to refine itself, it is evident that there are three major wells from which we draw our resources from. These are the cannon, modern leadership, and the witness of our own conscious through lived experience. In the October 2019 General Conference, church President Russel M. Nelson asked the women and girls of the church to prayerfully study Doctrine and Covenants 25 and seek to “understand the Priesthood power with which you have been endowed and that you will augment that power by exercising your faith in the Lord and in His power…”[18] Made evident by the expansive discussions, essays, and podcasts in response to this call, it is clear that the women of the church took this challenge seriously. The question I now have is, have the leaders of the church listened to the voices of these women who are sharing their lived experiences?

As women are included not only in the nomenclature of the Priesthood but also its responsibilities, leadership will diversify and the lived experiences of women will be both heard and considered, something that up to this point has yet to effectively happen, due to the current ecclesiastical structure of the church. It is without hesitation that I admit these suggestions are flawed, requiring additional consideration, re-working, and refining. This work also requires that those in places of privilege, specifically men, take up this work and place it at the forefront of what they give their attention to. In the meantime, thousands, if not millions of women are awakening to the existent power within them, and when moved upon by the spirit, are no longer hesitating to give life to those urgings, blessing all within their reach through their God and Goddess given powers. Authority is our daughter’s birthright, evidenced through the examples of the great Matriarchs Sarah, Rebekah, Leah, and Rachel; evidenced through the judgements of the Prophetess’ Deborah, Huldah, and Anna; evidenced through the courage of Mary, mother of God and Mary Magdalene, first among the Apostles, and as the catalyst of it all, through the wisdom and courage of Eve, our great Matriarch who, as Krakos points out, did not ask permission.[19]

Sources

[1] https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2021/04/49nelson?lang=eng

[2] https://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=58353062&itype=CMSID

[3] Daly, Mary. “After the Death of God the Father: Women’s Liberation and the Transformation of Christian Consciousness.” Woman Spirit Rising, a Feminist Reader in Religion, edited by Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow. Harper San Francisco, 1979. P. 54

[4] Ibid, 55.

[5] https://faithmatters.org/women-in-the-church-a-conversation-with-valerie-hudson/

[6] https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2021/05/08/latter-day-saints-are/

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 54.

[9] https://www.the-exponent.com/church-discipline-women-disciplined-by-men/

[10] https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics/priesthood?lang=eng

[11]https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2014/04/the-keys-and-authority-of-the-priesthood?lang=eng

[12] https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2019/10/02/major-change-latter-day/

[13]https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2019/10/03/jana-riess-why-its/

[14] https://atlastshesaidit.org/episode-035-wheres-the-priesthood-in-that/

[15] Krakos, Kyra N. (Spring 2020) The Order of Eve: A Matriarchal Priesthood. Dialogue, A Journal of Mormon Thought. Vol. 53, N.1, pp. 99-106.

[16] Ibid, 105.

[17] Ibid.

[18] https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2019/10/36nelson?lang=eng

[19] Ibid, 106.

Surely we can expand our nomenclature

to include the title High Priestess

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!