“a patriarchal system is inherently anxiety-provoking”

Amy is joined by Dr. MaryCatherine McDonald to discuss her book, Unbroken, exploring the ways we talk (or don’t talk) about trauma, the wear and tear of patriarchy on our nervous systems, plus exercises for responding to trauma, grounding, and empowering ourselves.

Our Guest

Dr. MaryCatherine McDonald

MaryCatherine McDonald, PhD, is a research professor and life coach who specializes in the psychology of trauma, stress, and resilience. She has been researching, lecturing, and publishing on neuroscience, psychology, and the lived experience of trauma and stress for over a decade. She’s passionate about destigmatizing trauma, stress, and mental health issues in general, as well as reframing our understanding of trauma in order to better understand and treat it. After receiving her master’s degree at The New School, where she researched traumatic loss and mourning, she went on to complete her PhD at Boston University. She has published several research articles and book chapters, as well as three books on trauma. Her most recent book came out in March 2023 with Sounds True Publishing and is called Unbroken: The Trauma Response Is Never Wrong, and Other Things You Need to Know to Take Back Your Life.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: If you look at the word “trauma” online and scroll down to see its usage, you’ll see that the word was almost never used in the 19th century. It picked up more usage in the early 20th century and then increased dramatically after the World Wars. And then, again, increased exponentially around 2019. It’s now so ubiquitous as to be heard nearly every day, sometimes in its technical, psychological context, and sometimes overused as slang, as in, “I just opened an expired yogurt from the fridge and was traumatized.” I have to say, even though the term trauma is overused now, I am so glad that we are talking about trauma more as a society. And I’m so grateful to have discovered the work of Dr. MaryCatherine McDonald, who is an expert on trauma and talks about the ways that patriarchy can cause and exacerbate trauma. I just finished Dr. McDonald’s book Unbroken: The Trauma Response Is Never Wrong, and I’m so excited to welcome her to the podcast today. Welcome, MaryCatherine!

MaryCatherine McDonald: Hi, thank you so much for having me! I am so excited to be here. I can’t wait to dive in.

AA: Awesome. I’ll read your professional bio. MaryCatherine McDonald, PhD, is a research professor and life coach who specializes in the psychology of trauma, stress, and resilience. She has been researching, lecturing, and publishing on neuroscience, psychology, and the lived experience of trauma and stress for over a decade. She’s passionate about destigmatizing trauma, stress, and mental health issues in general, as well as reframing our understanding of trauma in order to better understand and treat it. After receiving her master’s degree at The New School, where she researched traumatic loss and mourning, she went on to complete her PhD at Boston University. She has published several research articles and book chapters, as well as three books on trauma. The most recent book came out in March 2023 with Sounds True Publishing and is called Unbroken: The Trauma Response Is Never Wrong, and Other Things You Need to Know to Take Back Your Life and that’s the book that we’ll be kind of centering our discussion on today.

In addition to her academic work, Dr. McDonald has a thriving life coaching business. She’s worked with many different populations, including combat veterans, victims of sexual assault and childhood trauma, previously incarcerated folks, those suffering from the loss of a loved one, people going through career transitions, dealing with burnout, working to fix family dynamics, and more. She’s coached individual clients and corporations since 2010 and created trauma-based curriculum for nonprofit organizations in New York, Virginia, and California. MaryCatherine, that’s incredibly impactful and important work. And reading that list of people who are affected by trauma, I was just really moved hearing it, and then realized, I mean, I would think that almost everyone either has experienced something like that or knows and loves someone who has, so just the magnitude of the need really hit me and I just feel so, so grateful for your work.

MCM: Thank you so much. Thank you. It’s always held a special place in my heart, so it’s kind of a surreal, amazing thing when I see that echoed in other people and people see the importance of it.

AA: For sure. Well, let’s start out by having you introduce yourself to us a little more personally. Tell us where you’re from, some of the things about your education and your life experience that have led you to do the work that you do.

MCM: Yes. I grew up in Western Massachusetts in a tiny little town, and I was always interested in the way things work, whether that’s the universe, people’s minds, the whole of it. When I went to college, I started studying loss and things that kind of shatter our worldview. I was looking at identity, and then when I went on to my master’s degree, I really dove into the study of loss. I was looking at psychoanalysis and sort of the history of the study of loss, and then a lot of different case studies in literature and in psychology, trying to understand, why is this universal human experience so hard for us to talk about and grasp, and why do we make it so much harder on ourselves when it’s something that we all face?

When I switched to my PhD program, I kind of thought I was shifting gears entirely because I wanted to go back to the study of identity. What makes someone a self? What sorts of things form the self? How does the self get challenged through life? And there was this debate going on at the time about the extent to which the human psyche is a story, and there was this one very loud argument on one side that said we are not stories, our lives are not stories, and we do harm when we try to get our life to conform to story form. That seemed to me to be very problematic, and at worst, a sort of dangerous line of thinking, so I was looking for case studies that would show that even if you don’t necessarily know that you’re telling a story, that your life is a story, that it’s unfolding in story form. So I reached for trauma stories because trauma stories, one of the things I kept seeing out in the world is that people who’ve been through a trauma will often say “everything shattered and I had to pick up and start telling the story all over again.” So I reached for a case study and I wanted to write my dissertation on this debate. So I thought, okay, I’ll go to the International Trauma Conference and I’ll talk about trauma and I’ll figure out, how are we conceptualizing trauma right now?

And what I realized very quickly was that there was still huge debate in the field of psychology about what counts as a traumatic event. And I was shocked. That sort of took everything into a different direction and I started studying trauma. What is it? Why? Again, kind of in the same vein that I studied loss, why is this thing that is unfortunately so incredibly common, so hard to talk about? Why are we still arguing about what kinds of events are traumatic and which ones are not when we’ve been studying it for over 100 years? That’s when I started pulling from neuroscience and psychology as well as philosophy and looking at the whole field critically. What are we doing right? What are we doing wrong? How can we fix it? And I like to say, I got in trouble in an interview once saying this, but I kind of fell down a rabbit hole and just moved in and was like, “Okay, this is my space now. I’m going to figure out how we can talk about trauma in a better way.” Kind of simultaneous to grad school, I was working, I had a life coaching practice that I started, and all of these things finally came together in Unbroken, which is where I was able to bring together these three disciplines that I look at trauma from, as well as all my experience with my clients.

AA: Amazing. Yeah, thank you for that. That’s so interesting. I want to ask you one question about what you said, the debate between whether our psyche is a story or not. Something that I think about a lot is that once we acquire language, it seems like we do tell ourselves stories. Our experience has words to it, right? And it seems like that is just the way we experience the world, but I can see the argument that it’s dangerous because we can’t really rely on our brains all the time to be objective narrators of what actually happened, let alone what it meant. So, how do you trust– and that even leads me into your title a little bit, The Trauma Response Is Never Wrong. When do we trust our brains and our experience, and when do we not? Maybe that’s too big of a topic to ask about, but that’s something I think about a lot.

MCM: No, I do too. It’s really fascinating. There’s this whole issue, actually I was just emailing a student this morning about this issue of truth. I don’t know if you’ve ever read The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien.

AA: It’s on my bookshelf and I haven’t gotten to it yet, but I do need to read it.

MCM: Pick it up because it’s short stories that are about Vietnam, and Tim O’Brien is a Vietnam veteran, so that’s sort of on the face of it what the book is about. But there are many, many passages throughout the book where he kind of tackles this issue of whether or not you can ever tell a true trauma story. In other words, if trauma is something that sort of explodes the recording mechanism in our brain, and it’s so extreme that it sort of defies being wrangled by language, how can we ever say that we’re telling a true story? I think the answer to that is that we are very tempted to create a binary. A story is either true or it’s false. We can either trust our brains or we can’t. And the truth is almost always in the middle of that binary, which is that a partially true story still illustrates something accurate and a brain that sometimes makes mistakes is still trustworthy. So when it comes to the question, circling back to that idea of, like, are our lives a story? I think when we make that question a binary that’s when we get into trouble.

Let’s say I’m with a partner and I say this is my soulmate and I’m telling all these stories about the magical way that we met and why we’re so well matched and all this other stuff. If that partner starts behaving in a way that’s abusive or problematic, I now have two problems. I have to deal with the person and the dynamic that’s unfolding that’s abusive and problematic, but also I have to wrangle the story about how this person was my soulmate, and that’s really tricky. I think there are lots of examples like that, where we tell too tight a story that doesn’t allow any life or breath in it. But also on the other extreme, if our lives aren’t stories, then we can’t integrate anything that happens to us. And we know neurobiologically that the things we can’t integrate pose a problem for the brain. So, how can we then strike a balance and tell stories that have a little bit of breath, but also tell a satisfying enough story that our brains can kind of put them down? I feel like I just opened 14 cans of worms.

AA: Haha yeah, we could follow those threads and talk about that the whole time. Really interesting. But let’s dive into the topic of the podcast episode today, kind of going along with that, and maybe we’ll start by having you define trauma. What is it and what is it not?

MCM: So there’s the clinical definition and there’s my definition. I’ll start with my definition and then we can talk and kind of pull apart the clinical definition and talk about why we might want to pull that apart. In my opinion, in my research, anytime you have an unbearable emotional experience that lacks a relational home, you have a potential for trauma. Neurobiologically speaking, when you have anything that is significantly overwhelming to the point that it turns on your emergency operating system, you have a potential for trauma. Things become lasting trauma when you can’t find help integrating those incredibly overwhelming experiences. I think the most critically important thing to understand about trauma, because shame is the biggest barrier to healing from trauma, is that the trauma response that we come hardwired with to Earth is never wrong. It’s always a strength response, it’s always trying to protect you. We’re designed to go in between the emergency coping system and then out. It’s when we get stuck that the symptoms occur. But if we begin with this understanding that the trauma response is born of strength and not weakness, then we can peel away the shame, become empowered knowers of our stress response system and how it works, and learn how to regulate ourselves in the presence of trauma, how to integrate trauma, and then also how to regulate ourselves in the presence of triggers. That’s my definition.

AA: That’s great. Well, that leads us into another fundamental question for the episode, and that is what trauma has to do with patriarchy. There are going to be a lot of different ways of answering this, but the first question I want to ask you has to do with what you just mentioned, and that’s the shame piece, the shame around trauma. To me, when I was reading your book, that was my first thing. This definitely has to do with patriarchy. Can you talk about that?

MCM: Yeah, I think we sometimes turn a blind eye to the history of a thing because we assume that we have this definition that we work with right now and that’s all we need to know. But if you start to peel back the layers of the history of the study of trauma you immediately get to oppression. The history of the study of trauma begins with this concept that was called “hysteria” in the 1800s. This was sort of a catch-all diagnosis for women who were misbehaving in one way or another, and these women were neglected and abused in the name of “treatment” and they were thought to be the most difficult patients. That’s not something that we ever talk about when we talk about trauma. I think it’s really, really important that we understand that the study begins with the oppression of women and then immediately turns to the oppression of men. The first population of folks that were being diagnosed with what we now call trauma, what we called hysteria then, were women who were dealing with sexual assault in their childhoods. It was studied very intently for a couple of years, and then everyone, Freud, Charcot, that whole kind of cohort of people realized that all of their clients had the similar stressor, which is that they had been abused by these higher-ups in society. What that meant was that for them to continue their work, they were going to have to call out these people in society, so they abandoned their patients.

if we begin with this understanding that the trauma response is born of strength and not weakness, then we can peel away the shame…

The next time we see the set of symptoms come into the clinic, it’s after World War I and now we have soldiers who are having these same “weak” symptoms that only used to happen to women. And this is not just sort of societally, but the way that they were treated in the clinic was to be humiliated, to be called weak. “You’re not a man.” There was all this patriarchal language built into the literal treatment modalities. They would stand these soldiers up and say things about them like, “Behave like the man that I expect you to be.” Kind of ordering them to stop their symptoms, which were assumed to be a sign of a weak character, weakness of will. So we imported this idea that to be traumatized is to be feminine, and to be feminine is to be weak and broken. We inherited that into the study of combat trauma, and we still use that language, maybe not in the treatment spaces, but we still talk about soldiers that come back from war, who are largely male, as if the ones who are suffering from trauma have something wrong with them. So patriarchy is entangled in the definition and the history of this term. And if we don’t understand that, we can easily perpetuate that into the future.

AA: Yes. That is really, really striking and really heartbreaking.

MCM: It’s so heartbreaking.

AA: It really is. And you’ve done a lot of work, like in your bio it’s mentioned that you have worked with veterans and people who’ve been through combat.

MCM: Yes, and also clinicians who are working with combat veterans and family members who are dealing with combat veterans, and I can tell you that this idea that if you’re struggling it’s a sign of weakness is still very much alive. We know now not to say it as broadly as we did before, but that’s the fear, that’s the shame, that’s the thing that brings people into the clinic. When I started working with combat veterans, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were going on and clinicians were having to hold all night hours because the soldiers didn’t want to be seen going into treatment. They would go in the middle of the night. And that’s not that long ago, you know what I mean? We’re not talking about 1820, this is like 2016. It’s very heartbreaking. And then I think there are some– I don’t know if I want to call them funny, but there are these ways that we bring old practices that were torture into present society and pretend like we’ve created them. An example of this is the cold plunge. That was something that was done to women in asylums in the 1800s where these women were, again, if they were misbehaving, plunging someone into cold water is a great way to shock their system and get them to start behaving. And so this is where that came from. Yes, it regulates the nervous system, but I’ve never heard anyone except me talk about that. It’s like we’re bringing this practice into our present and future without any mind to where it came from and what it might have done to the people that it was first used on.

AA: Yeah, that’s kind of crazy. I know that’s like a big trend right now, the cold plunging. Are you not a fan of cold plunging?

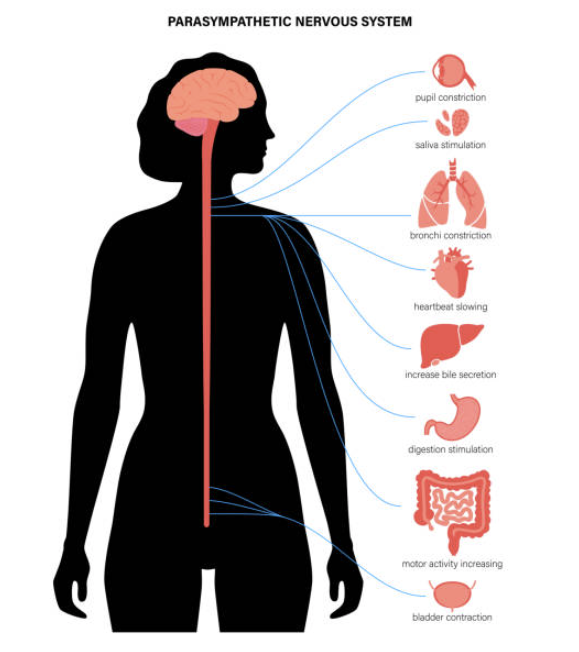

MCM: First of all, I think that people, when they want to consider it, they need to check with their cardiologist because it is a shock to the cardiovascular system. And if you have an underlying issue you don’t know about, that can be deadly. I think not enough people talk about that. But cold water does activate the parasympathetic nervous system and bring on the kind of rest-and-digest response. It can be incredibly regulating to the nervous system, I just think we need to give a nod to where these things come from.

AA: That’s fascinating. Yeah, totally. The next direction that I wanted to go was, you talk about in your book that rather than labeling the trauma symptoms and trauma response with obviously all of these minimizing and diminishing labels that people have done, you talk about how we need to reframe emotions as biological events, and the emotions that happen with trauma fall under that, too. Can you talk about that, that emotions are biological events?

MCM: I wish someone had told me this in like the second grade.

AA: True!

MCM: Because if little ones were empowered to understand that their emotions– I think we have this narrative in society, and again, this comes directly from patriarchy, that if you’re having an emotion, you must manage it. And if it is sort of escaping you, then you’re doing something wrong. You must behave. You’re not being disciplined. So we discipline ourselves and we learn how to do this in school, and then it gets perpetuated through our whole lives and then when we’re dealing with something really tough that can’t be managed, then we’re at a loss, right? I don’t know what to do if I’m having a panic attack in the subway or if I’m having a grief wave at work or if I’m triggered by something and I don’t even know how to connect the dots between the trigger and the emotion. So I think the first step is understanding that emotions are not things that we choose, they are not things you can opt out of, they are not to be managed, they are a natural biological process, just like hunger and digestion. Is hunger and digestion sometimes inconvenient? Absolutely. Is it embarrassing when your stomach is upset and you’re on a date? 100%. But you wouldn’t turn to your body and shame it for having those biological responses. It’s wild. We need to reframe that immediately.

And I think if we start there, then we can start diving into, okay, what are the most typical emotions that come up when you have a trigger and how can you recognize them in your body? Because I think we’re not as good as we think we are at that. And then what do you do about them so that you can have a little bit more of a say when an emotion starts sort of bucking through your body and you’re like, “Whoa, I’m in a meeting!” Because there is a lot more that we can do to bring ourselves back down to baseline when those trauma responses – fight, flight, freeze – come up and kind of get in the way.

AA: And tying these two issues together, can you tell us about PTSD a little bit? You talk about that as a constellation of symptoms that are rooted in the body. So emotions that are biological events, and that’s different from how that’s been thought of in the past, right?

MCM: Yeah, this is another place where the history of the study of trauma is so fascinating. The first thing in the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is how we diagnose PTSD, PTSD didn’t show up in the DSM until the 1980s. This is a very new designation, and it has been called many things. The thing that is most up for debate typically is the stressor, like, what counts as a trauma. Because in order to have PTSD you have to have been exposed to something that was a traumatic stressor. And this definition has shifted really starkly through the history of the DSM, which gets revised every handful of years. It used to be, I wish I could remember the language off the top of my head, it used to be that when someone was faced with something that was significantly outside the norm and it causes distress, then you have the exposure to a trauma. There’s no attempt there to kind of pin down which events are potentially traumatic and which ones are not, it was just whatever’s out of the norm. They had to switch that because unfortunately trauma is not out of the norm, so that distinction seemed like it was going to do a lot of work and then it ended up kind of falling apart.

The result is that right now we have a very narrow list of things that are potentially traumatic in the clinical spaces. Now, different clinicians can, of course, interpret the DSM based on their own experience, but right now it’s death, threatened death, violence, threatened violence, or sexual assault. Those are the three things that can be potentially counted as traumatic. And this disregards, of course, so many other things, right? Being bullied at school or work, going through a psychologically abusive relationship, having neglect in your childhood. All of these things can cause the same kinds of responses. So I think that’s a very long way of saying that we need to move, this is very clear from the science, from an event-based definition to a response-based definition. When your body is significantly overwhelmed, it has an incredibly sophisticated adaptive mechanism that turns on to help keep you alive. And that brings us to these responses of fight, flight, and freeze.

When your body sees a threat and thinks it can fight it, it makes that decision without the input of your rational mind and it will fight. What that means is that 47 different parts of your brain and body alter their function immediately, in a millisecond, to figure out how to handle this threat and stay alive. The same thing is true with flight. That’s when your body sees the threat and says, “Okay, I don’t think I can fight this bear, but I can probably get away.” And then all of your resources are sent to the parts of your body and brain that would help you get away. And freeze happens when you realize that you can’t fight and you probably can’t get away, so your body, again, adapts by shutting down pain receptors and disconnecting from consciousness a little bit. This is what gives you the symptom of feeling outside of your body, which sounds awful, feels awful, and certainly is awful as a symptom, but protects you in that moment from pain and shock and awfulness. So, these biological responses are there for a reason. And again, they’re a strength response, not a sign of weakness. They are the things that have kept us alive until this point. We should celebrate them, not call them a sign of dysfunction.

AA: That makes sense. Okay, this brings us also to a lot of the causes, since we’re talking about causes of PTSD, a lot of the causes of all the kinds of trauma that you’re listing actually do have connections to or roots in patriarchal systems, right? We talked about war, sexual violence, I mean violence of any kind, but specifically sexual violence. Can we unpack that for a minute?

MCM: Yeah, and I think this is a place where, I’m sure you get this all the time, I think it’s very important that we understand that a patriarchal system hurts everybody. It begins with the oppression of women and minorities, and then it kind of turns back on itself, and ends up hurting everybody. We’ve talked a little bit about shame, and I think one of the things that makes it the hardest to heal from trauma is that we can’t admit that we have it because it’s viewed still as a sign of weakness. But then when it comes to what causes trauma, these are almost always relational harms that come from disrupted power structures where people are either trying to wrangle back power for themselves or cope with having their power taken. If we really want to heal trauma– I haven’t gotten this question in a really long time, but I used to sometimes get this question: “Once we learn how to heal trauma, what are you going to do? Because trauma is your thing.” And I was like, “Well, I’m interested in a lot of things, I’ll be just fine.” But we’re never going to get rid of that because we don’t seem willing to dismantle the structure that it appears within. We can’t even look at it on a large scale. And until we’re able to do that, we don’t even need to think about the question of “what are we going to do when there’s no trauma?” We’re not in that universe. You know what I mean?

AA: Yeah. It brings me back to our very first episode on the podcast, Rianne Eisler’s The Chalice and the Blade, and how she identifies two different types of social structures. One is dominator culture and one is partnership culture. And unfortunately, I just don’t think, given a lot of human nature, that dominator culture is going anywhere. My family was just talking about Napoleon yesterday, randomly, we were talking about France and conquest and wanting land and wanting resources and just saying “I’m going to go in and take what I want.” And we have a culture that prizes that and militarized masculinity. Not all humans are wired that way, but a lot are.

MCM: Yeah, it’s interesting. Where does the wiring come from, and how much of it is societal? Because I think that maybe 15 years ago I would have been a lot more optimistic. Yes, we’re looking at the patriarchy, we’re looking at these structures, we’re dismantling them, there’s so much positive change. But if you just think about the pandemic, what a power grab public health became, right? Like, “We don’t know how bad this is, let’s wear masks, let’s have mandates,” and then it was immediately, “You’re taking my power, I must take it back.”

And we’re still dealing with that. I’m really fascinated right now, this is maybe off topic, but just the way that these power dynamics have started to infiltrate everyday life in ways that are really destructive. I live in a really small suburban town that’s very peaceful, typically, but since the pandemic, I’ve recently seen two women have a traffic incident and both of them get out of the car and scream in each other’s faces. We are so aggressive right now, and I think it’s because we’ve had our power pushed on, and even the perception of that makes people turn to this rage response. That’s the fight response. What are we responding to? To our power being taken away or maybe just diminished. I just think that it’s way worse than I would have thought.

it begins with the oppression of women and minorities, and then it turns back on itself and ends up hurting everybody

AA: No, I think that’s true. And even just considering war all over the world, boy, we could talk about this for a long time about whether it’s nature or nurture. But I do think, I guess what maybe everyone can agree on is that, yes, there is this dark side of human nature that does get triggered and we are an aggressive species, we have that in us if there’s scarcity, if we feel a scarcity of power, scarcity of food, scarcity of land. But in certain cultures, if that flares up, certain cultures will say, “No, we’re going to learn how to manage those emotions so that we can be a partnership because in this culture, we value partnership.” Other cultures will reward the aggression and they’ll frame it as masculine and frame that as like, “No, that’s how you prove yourself to be a good man.” And when that happens, then heaven help everybody.

MCM: Right, right. Absolutely. I was very influenced in my master’s degree by Judith Butler, who wrote a book called Precarious Life, and one of the chapters in there is called ‘Violence, Mourning, Politics’ and she wrote it right after September 11th, and she was sort of musing about the American inability to grieve publicly. How George Bush got up – and this doesn’t need to be political, I’m trying to make a comment about something emotional – he got up like eleven days after 9/11 and said, “Okay, grief is over. We now must go to war.” What a fascinating juxtaposition, that sadness is a luxury we cannot afford, we must go to war. That was the biggest thing that had happened in our country, and to grieve was to be weak. It’s still there. Grief is just an emotion. It’s a big one and it feels like an ocean, but it’s an emotion. We can’t turn away from these things. And it’s the same thing with the pandemic. The core emotion was terror. We were afraid, but since we can’t admit that, we can’t integrate it. And when we can’t integrate it, it turns into aggression, and that has to be framed as virtuous, you know, it’s masculine, and we are fighting.

AA: Mm-hmm. Yeah, for sure. It is really, really tragic. Another one of these topics where I do feel like patriarchy is in many ways at the root is how common it is to have abuse within heterosexual relationships. Can you talk about trauma bonds and why many women find it difficult to leave abusive men, and then as well as how men find themselves in abusive roles? Because that’s the cause of a lot of trauma.

MCM: Yes, a lot of trauma. And it can be kind of invisible because of the way that we define trauma clinically and societally. We say, “Well, he never hit me,” right? If that’s the case. So it’s not a trauma bond, and we can do incredible damage psychologically without ever raising to the level of physical violence. I think it’s helpful to start with what a trauma bond is not, because I don’t know about you, but I see this misdefined everywhere, misused everywhere. Trauma bond is not when you’ve gone through a similar trauma to someone and you’re bonded because you’ve had that same awful boss or you had that same deployment. That’s not a trauma bond. And a trauma bond is not when you’ve been sort of taken against your will and you start having fond feelings for the person who has kidnapped you, that’s Stockholm Syndrome. It’s important that we define these terms again because it’s important to think about where they come from.

A trauma bond, this term came from the study of abusive marriage in America. I can’t remember if it was the 60s or 70s, but researchers were like, “Okay, we’ve got the American Dream and yet for a significant percentage of people, this American dream becomes violent. What the hell is going on?” So the researchers invited men and women into their clinics to try to understand what was going on, and they separated the men from the women. They asked the men, “You don’t have a criminal record, you’re an upstanding citizen, you have a job, you have a house, you have the white picket fence, you have a wife, what’s happening?” And the men kind of uniformly said, “I’m not a violent person, I’ve never been violent before, but my wife pushes my buttons and then she gets sympathy for it. And she knows exactly what to do, she’ll wait until it’s the end of the day,” you know, this whole thing.

The researchers wrote all that down, and then they went to the women, and they said, “What’s going on? You have the American Dream, your husband is providing for you, you have a white picket fence, you have kids, you have a dog, what’s going on?” And they were pretty silent. Notably, the researchers were men. So the researchers came away with these two pieces of data and they said, well, the men don’t have criminal pasts and they’re beating their wives and the wives seem to have the same personality: they’re cold, they’re disconnected, and according to their husbands, they seem to kind of want this drama. This assumption was termed masochistic personality disorder, and it actually entered the DSM. This was considered a mental disorder for, I think, two decades, and all of the research about abusive marriages came from this hypothesis, which is that women who end up in abusive situations want to be there, and men are pushed by these women to behave in ways they wouldn’t otherwise. That’s, of course, completely false.

There were these two researchers, Donald Dutton and Susan Painter, that came about. So, none of the interventions worked for the people. Shocking, because the hypothesis is completely wrong, right? This is what happens when we have bad science. So Donald Dutton and Susan Painter came along and they were like, “Hold on, what is going on here? What’s actually going on here? Because this structure seems problematic and flawed. Let’s see what else we can find.” And what they realized was that the nature of the relationship sometimes between two people has a power dynamic in it that causes both people to sort of splinter from themselves and start behaving in ways they might not otherwise. And then it spirals. You have one person who has more power, and that could be financial, social, it could be anything. And then the other partner feels diminished, and this cycle starts where the partner that has more power intermittently abuses the partner that has less power. Since it’s intermittent, it’s fundamentally confusing because it’s not just that the person is terrible and abusive all the time. It’s that they’re terrible and abusive and then they’re incredibly kind for six months. And then there’s a flare up and then they make up for it and they’re incredibly kind.

The super fascinating thing is that we now know what that kind of cycle does to the brain, because the question is, well, if we all understand what a trauma bond is, why is it so hard to get away? Because I think it takes, I can’t remember if it’s an average of seven or nine times to actually get away from an abusive situation. It’s not easy like one and done. “Oh, I’ve realized this dynamic, I must get out.” And then that’s it. Because it’s so intermittent and confusing. What the neuroscience shows is that when you’re in a situation like that, you actually become detached from the structures in your brain that are responsible for knowing you, you as a self and making decisions as a self. If you’ve ever been in a situation where you’re like, “I don’t even know who I was before this relationship. I can’t get out of it because I don’t even remember what I like.” I’ve asked clients before, “Okay, let’s start really small. What’s your favorite color?” “I don’t know,” is the answer. That’s how disconnected those brain structures become, which is heartbreaking. It’s also very hopeful because the way out is to recognize that you’re in that situation and then start gradually, and you can do this even while you’re still trying to get disentangled, reconnecting to the parts of your brain that know yourself as a self. Sit and think about what your favorite colors are. Look at the color wheel, make yourself a playlist. What were the hobbies that you liked before this person was in your life? All this other stuff.

But going back to your question about how this is patriarchal is that we tend to make a binary, again, and we say we have a perpetrator and we have a victim. Perpetrator is bad, victim is good. What we need to understand is that nobody, very few people enter into a situation with an intent to abuse, and so we have to be willing to really bravely look at that dynamic and hold judgment and say what has changed about both of these people in this dynamic and why. What you see is that when a partner has less power and they’re male, for example if they make less money, they are emasculated because they’ve been told their entire lives that their one sole purpose in this world is to provide. So when their wife is making more money, then they have to wrestle with that story, that societal story that’s telling them that they’re not enough. And that when you can’t talk about it, when you can’t integrate it because we take emotion to be a sign of weakness rather than a biological event, it will come out in aggression. That doesn’t mean it’s okay, of course, I’m not saying that that’s okay. But we need to understand it if we want to fix it. And that’s, I think, what Donald Dutton and Susan Painter had started doing, and I think we can pick up that project and keep working on it.

AA: One thing that I’ve observed in some of the men that I know, and this is a way that I think patriarchy hurts men and everybody too, is that even just the title of Simone de Beauvoir’s work, The Second Sex, it creates an expectation in boys from the time that they’re little that they are the primary person. So they have these expectations that sometimes they don’t even really know they have. I’m just thinking about the men in the study that you mentioned, like, “I come home, I’m tired, and she’s just creating problems.” And I can just imagine that perhaps these men have expectations of the way things should be, and their lives have taught them that that is the default, so for this marginal person to come in and be like, “But wait, I have a point of view,” it can be infuriating because you’re like, “Wait, what? You’re messing things up. The way I want it is the default and the primary position. You’re the one who’s causing problems.” And then further, like you said, if patriarchy hasn’t given them any tools to deal with their emotions when they get upset because you can’t show that you’re upset, you can’t show that you’re sad, you can’t admit that you’re vulnerable and that you’re worried by the thing that this woman says, all you can feel is anger, then they have no tools to manage their own emotions and then it just erupts into abuse because you haven’t learned the tools and you also haven’t learned that you’re dealing with your equals. At least that’s what I’ve observed in some of the relationships that I’ve seen where patriarchy has done men no favors.

MCM: A thousand percent, and I think we need to understand, too, you just put that so beautifully, it’s like, okay, well, if we can understand that, why don’t we just change? But I think we need to understand that we inherit these power structures, they are pre-linguistic. There’s no conscious connection unless we put it there. I worked for a couple of years with previously incarcerated gang members, almost all of them were male, and there was no understanding, no connection, because they had never been taught that aggression can come from sadness, that violence can come from neglect and a lack of belonging, that they weren’t monsters. There was tons of trauma there. And that when we are left to our own devices and traumatized and in danger, of course we will fight back. Again, that doesn’t make it okay, but it makes sense. And if we can empower people to understand, okay, notice that you’re feeling aggressive. Step one. Your body is a barometer. What is it feeling? You’re feeling aggression? Okay. That’s an indicator light. Something is up. What’s up? Where is it coming from? Who can you go to to talk about it? If we can institute some of these very simple structures, then I think we can do a lot of work to prevent this kind of thing. Not all of it, of course, but a lot of it. But you’re right. It’s that these things are taught, it’s like they’re infused. I think that a lot of men don’t even have the realization that they’ve been taught that they have to provide. They just have this sort of vague, amorphous feeling that that’s their role. And if they’re not doing it, the way that shows up is “I’m a failure.” It doesn’t show up as “I’ve been taught to provide and I’m not providing.” It’s just a feeling.

AA: Yeah. That it’s so hard for them to face. And then I can imagine, too, that if they don’t have the language around that to be able to process and understand that, then maybe in some circumstances, even seeing the woman that they’re supposed to be providing for is just a reminder of their failure and she doesn’t realize that’s what she’s representing to him, and then it comes out at her and neither one really knows what’s happening. It’s just kind of a mess.

MCM: Yep, and no one has the language to unpack that. It just turns into an argument at dinner that blows up. And it can also happen the other way around. I think that it’s important to understand that even though we’re talking about a heterosexual model here, women are taught about power too. It’s not just that men inherit these structures, we also do. So when we have an expectation and we say something to our partner, like, “You’re not making me feel safe, and that’s your role, because you don’t have enough money,” that’s tapping into the same structure, you know?

AA: That’s interesting. So you say that even same-sex couples, like a lesbian couple for example, might have unhealthy structures in the relationship that actually have their roots in patriarchy, even though they’re not being enacted by a man, right?

MCM: Right, right, and we ask them, “Who’s the breadwinner? Who’s the man in the relationship? Who wears the pants? All of this stuff is so gendered.

AA: Right. Interesting. All right, we’re going to shift gears a little bit and I want to ask you a different question. I was listening to a podcast episode one time, I don’t remember which podcast it was, I don’t remember the people who were on it, but they were talking about physical symptoms that women experience frequently. They were talking about digestion and specifically constipation because that’s more common in women, I think, chronic constipation, and this woman was asking the expert, “What causes that?” And the expert said, “Patriarchy.” And I, like, guffawed. If I had water in my mouth, I would have spit out my water like “What?” I was so shocked and I laughed, I was like, “What in the world?” She didn’t elaborate on it at all. She just said that and that they proceeded to talk about the physical symptoms of digestive troubles and stuff. But you talk in your book about referred pain, and that there’s this whole fascinating world that I know nothing about in terms of how our social-emotional selves are connected to our physical selves. Can you talk about that a little bit?

MCM: Yes. I think we want to make a distinction between the mind and the body, and that makes a lot of sense because of the way that our society works and how we’ve been taught. We want to say that the mind is the seat of the soul and the body is to be managed, essentially. We detach from ourselves, which, even without any trauma at all, causes a lot of problems because your body is a barometer that’s giving you information all the time. If you’re detached from it, you are also detached from that information. Bessel van der Kolk, of course, coined this phrase that has become very famous, which is “the body keeps the score,” right? And that is true. Your body is along for the ride, no matter what you are doing. Joy, resistance, anything that you’re going through, and trauma as well. And so when we see symptoms in the body, it’s usually because we cognitively think we are “over” something or we’re not upset or we’re not stressed and our body is telling a different story. So the nervous system is broken. I mean, we could talk about the nervous system for a whole other podcast, but there are three branches of the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system is in charge of all the things in your body that are automatic, that don’t happen without your conscious input. Your breathing rate, your heart rate, your digestion, your reproductive system, all of that stuff. There are three branches of the autonomic nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system is responsible for activation. When the sympathetic nervous system is on, everything gets up-regulated. Your blood pressure will go up, your heart rate will go up, all this other stuff will go up. And that can either happen because you’ve got a stressor or a threat, or just because you’re exercising, which is also a stressor, but we think of it differently. The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for rest and digest, so we kind of toggle between these two stages, and we’re designed that way. The enteric branch of the nervous system is the part of the nervous system that’s responsible for digestion. We don’t control that consciously, though I think many of us wish that we could sort of issue a directive to our stomach and it would do what we need it to do. It is sort of at the mercy of the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches and will behave differently depending on which one is on. That can result in all manner of digestive issues, whether that’s constipation or the opposite or just nausea, any of that kind of stuff can happen. That is an incredibly common feature of trauma, anxiety, stress, anything. A patriarchal system is kind of inherently anxiety-provoking for everyone because it’s about power and the struggle for power. When you’re in an oppressed minority, that could result in a feeling in your nervous system, again, not necessarily a conscious feeling, but a feeling in your nervous system that you are being oppressed and that you’re in danger, and your nervous system is going to respond accordingly because that’s what it’s built for. And so that gives us these symptoms that are inconvenient, but may, again, make a ton of sense. So I don’t know if we can say that patriarchy equals constipation, but being sort of at the mercy of a power structure like this could certainly affect your digestive system.

AA: Very interesting.

MCM: I know, it’s crazy.

AA: It is crazy. And is there something else about referred pain?

MCM: Oh, yeah. Sorry. Yes. So, referred pain I’m fascinated with just because it’s such a mysterious thing, and I’m fascinated with it because it provides a beautiful metaphor, which is that we think we are very good at pinpointing the source of our problems consciously and physically, and the truth is that often the pain is coming from elsewhere in the system. Referred pain is the biological phenomenon whereby you have pain that shows up in one area, but the source is actually something completely unrelated. The classic example of this is when you have tooth pain, you go to the dentist and they tell you there’s absolutely nothing wrong with your tooth, you must go to the emergency room right away because the thing that it’s being referred from is your heart. It can also happen with the spleen, which can cause shoulder pain for some reason. There are all these other things.

I see this in clients all the time who come in with, and I want to be careful with this because it’s not like I’m the power in this situation to be able to be like, “No, your stressor is here.” We discover this together, but clients will come in all the time and say, “I’m really stressed at work. I think I might have to quit my job.” But then we start talking about work and it’s clear that they love it. And so it’s like, well, hold on. There’s pain in the system, there’s a symptom here, but what’s the actual source? Let’s dive a little deeper and try to figure out if the pain is being referred somewhere else before you go and quit your job. And we can see this, of course, throughout our lives. We are not that great at deciphering when we are stressed and why, whether that’s just run-of-the-mill stress or stress that raises to the level of trauma. It’s important that we understand, again, that there’s pain in the system. Here’s the symptom. I might need help figuring out where it’s coming from.

We are not that great at deciphering when we are stressed and why, whether that’s just run-of-the-mill stress or stress that raises to the level of trauma.

AA: That’s so interesting and it makes me think of so many specific women I know who interestingly defend the system of patriarchy, conservative religious women who are like, “Nope, this is the way God wants it, and I’m actually really happy with this system,” but then they have so much dysfunction in their lives and actually tons of depression, tons of anxiety. But they will not confront the possibility of what the underlying cause of that depression and anxiety might be. They’ll refer the pain to all kinds of other things. “No, it’s this, it’s that, but it’s definitely not that I have no power in my marriage because of A, B and C.” It’s frustrating.

MCM: Oh, and I love the way that you just said that because we can refer the pain ourselves. We can send it somewhere else like, “No, it’s this place. It’s this thing.” It’s not something we’re at the whim of with our body. Send it somewhere else.

AA: Yeah, totally. Interesting. Well, as we are heading for the end of the conversation, which I wish we weren’t, because there’s so much that we could talk about, I wonder if we can have you talk about some tools and grounding exercises for when we’re experiencing trauma. What can we do that can help?

MCM: Yes. One, I’m going to give you this and it’s so quick, but we can actually do it here right now. It’s always such a fun little thing. We talked about the parasympathetic nervous system and we actually have access to the parasympathetic nervous system through something called the vagus nerve, which you’ve probably heard of because it’s been kind of heralded all over everywhere, which is really exciting. I was actually researching some of these external vagus nerve stimulator devices yesterday because I’m curious. The vagus nerve is kind of in charge of turning on the parasympathetic nervous system, which is what makes you feel calm. And there are two spots, it’s called vagus because it wanders all over your body and it touches all of those organs that are responsible for the stuff that happens automatically in your body, breathing and heart rate and all that stuff. There are two spots where it has tons of nerve endings. One is in the back of your throat and the other one is right in front of your diaphragm. So we can feel a marked change in stress by taking three breaths into the diaphragm. Do you want to do this together?

AA: I do. Yeah.

MCM: So to find your diaphragm, you just put your hands kind of in the middle of your torso, it’s right underneath your ribcage. You know how sometimes in yoga they tell you to breathe way low in your belly? It’s not there. And it’s also not the kind of breaths you’d be taking if you’re going for a run, like up in your chest. You want to shoot for making your hands kind of expand out with your ribs. And then you’re going to take your ab muscles and push the air out and your hands are going to go in. So we’ll do that just three times. Ready? One. Take a deep breath in and then out. I already feel different. And two. In and hold. And then all the way out. And then three. One more. In and hold. And then push all the way out. Do you feel any different?

AA: That’s great. I need to do that more often.

MCM: I know, right? I love doing that when I’m doing a podcast or presenting because I get so excited, which is the sympathetic nervous system, right? It’s not all bad. And then I take three breaths and I’m like, “Okay, let’s land.” I love that one because you can do it in the grocery store when you’re having a panic attack, you can do it in the car when you’re stuck in traffic or someone just cut you off. Does it fix everything? Of course not. But you are three breaths away from feeling a little bit better, and I think that’s a super handy tool when you’re in conflict or you’re stressed out or anything. Other grounding exercises that I love, I have a practice called tiny little joy. I actually just wrote a book on joy and joy for folks who struggle with joy, who have a trauma history. And tiny little joys is designed as a way to reintroduce joy into your life when you’ve been dysregulated by trauma or joy or both, because we can become dysregulated by all emotions. The idea is that you just take note in your daily life, and again, we can do this right now, of one thing that sort of sparks a little bit of joy in your body. And you notice it and you sort of lean into it for a second and then you let it go. The idea is that you’re bringing joy in, but not in this huge way to make this celebration and dysregulate your whole nervous system. You’re just like, “Oh, that’s something I like.” And then you put it away. And it’s when you’re in that joy space, you’re actually by definition turning down the fear center of your brain. If you practice that and you can do it a couple of times a day, you’re actually starting to rewire your brain.

AA: I love that. I love how easy that is, yes. And like you said, how practical it is that you could do either one of those things, anywhere you are, like in a grocery store. And as I’m now tying this to patriarchal systems, thinking of the practical applications of that, if you’re walking into a space where maybe you’ve been conditioned to think of yourself as lower in the hierarchy, that I’m the one with less power and this person maybe is abusing it, whether it’s a boss or a co-worker that isn’t your boss, or a father or a husband or a church leader, where you’re like, “Oh, how do I rewire this? How do I ground myself and not feel this anxiety or feel this way that I know that I’m weaker?” And just thinking of doing the breaths, thinking of something joyful, it’s empowering too, right? Level the playing field, even in just that relationship, right?

MCM: Completely. And another one you could do is a tiny little power stance when you’re in a space like that. That’s incredibly helpful. Standing in mountain pose in yoga where your feet are right underneath your hips and you turn your arms out so your palms are out and your shoulders are back and just standing like that in church or in the kitchen or any of these spaces where you’re like, “I’m feeling really blown around by the wind of other people and I feel like I don’t have power.” You might not be able to externally resist in that moment because of safety or because of other concerns, but if you could stand in mountain pose and say to yourself, “I have power,” in your head, “I have power. I have power,” that’s going to do something to your nervous system. It’s not going to change the moment or the situation or the person that you’re in front of, but it’s going to change how you feel, which will then change how you engage. And if we all do that, then we can start shifting the system.

AA: Ah, amazing. That’s so great. Well, MaryCatherine, thank you so much for this conversation. I’d love to close by having you tell us where we can find your work because I was so impressed with your book. I know you have a fantastic Instagram account, so tell us where to find you.

MCM: Yes, so I’m @mc.phd, both on TikTok and Instagram, and my website is alchemycoaching.life. And Unbroken you can find anywhere you find books. You can get it at an indie bookstore or on Amazon, and it comes in the physical copy. There’s a Kindle copy, and there’s also an audio version that I read, which was really fun to record.

AA: Oh, I should have done that. I should have listened to it. I read the book and loved the book, but it’s good to know that you can listen to it too. That’s awesome.

MCM: I love it when authors read their own stuff cause it’s like they know all the secrets.

AA: Yes! Oh good. Well, excellent recommendation. I highly recommend it to listeners. And again, Dr. MaryCatherine McDonald, thank you so much for being here today.

MCM: Thank you. This was so much fun.

your nervous system is going to respond

because that’s what it’s built for

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!