“growing up in patriarchy had severed me from parts of myself”

Amy is joined by Alicia Galbraith & BreAnna Larson who turn the table and interview our host about her experiences with the plant medicine Mamá Ayahuasca. This episode is Part Two of Two and covers the experience of an ayahuasca ceremony and how plant medicine can offer healing and revelation.

Our Guests

Alicia Galbraith

Alicia Galbraith is passionate about mental health. With a background in neuroscience, yoga, and meditation, she is currently pursuing a Masters Degree in Social Work with the intent to become a therapist. She believes each client she meets with has the tools for their own healing within themselves. In sessions, she pulls from her varied background, clearing the path for whole-person healing, with the firm belief that each client holds their own medicine.

BreAnna Cox Larson

BreAnna Cox Larson lives in North Salt Lake with her husband and four kids. She is the Chair of the NSL Planning Commission, the Co-founder and Chair of the Davis County Women’s Caucus, and a member of the Stakeholder’s Committee for the Davis School District. She volunteers as a citizen lobbyist with a focus on empowering citizens to get involved in their communities through boards and commissions to impact municipal-level change. She and her family own a small hobby vineyard and enjoy skiing and riding motorcycles together.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In many places all over the world, all through recorded time, societies have written stories about heroes. There are many elements of the hero’s journey that occur across cultures and across centuries, and one of these archetypes is the hero’s descent into the underworld. Often, the protagonist needs information, sometimes there are demons that need to be fought, or unresolved relationships that need to be worked out and the only way forward is into some dark, scary cave, or down into the land of the shades or the spirits. These descents appear in the Epic of Gilgamesh in Mesopotamia, and in many stories within Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, apocryphal Christianity, and Norse mythology, among others. In ancient Greece, they called the hero’s descent a katabasis, from the Greek words katá, downward, and baínō, go. Famous examples of katabasis in Greek mythology include Orpheus, who enters the Underworld to save Eurydice from Hades, and Odysseus, who needs information from the prophet Tiresias and then encounters many different people in the Underworld who help him on his journey. As terrifying as it is to descend into the dark, the hero is safe and he emerges transformed and empowered to finish his quest. Or her quest, as the case may be.

On our previous episode, our guest Tlawil Castillo told us about the use of the plant medicine, ayahuasca, in helping people learn, grow, and confront difficult truths in order to become the people they are meant to be. Today I’ve decided to share my own story of descent and learning with Mama Aya. To help me tell that story, I’m joined today by Alicia Galbraith and BreAnna Larson. Alicia and BreAnna shared two episodes on Grandfather Peyote, and I’m so excited to welcome them back to the podcast today. Welcome, Alicia and Bre!

BreAnna Larson: Thanks for having us back, Amy.

Alicia Galbraith: Thank you so much. We’re so excited to be back here.

AA: I’m so excited, but I’m also a little bit nervous because the three of us spoke about doing this episode on ayahuasca, and we’re turning the tables today. So BreAnna and Alicia are going to be interviewing me and I’m just going to turn it over to you. And with great trust, I am making myself very vulnerable and you can ask me any questions you want. So take it away, guys!

BL: Well, yes, this is very exciting. I don’t even know where to start. What do I want to know about Amy? Just like you are so generous to introduce us to so many people that you interview on your podcast, I would love to hear a little bit about your history and what brought you here to this space. Tell us a little bit about you, Amy.

AA: So, my people come from lots of different places. On my dad’s side, my ancestors are mostly Scottish, with a little bit of English, and a little bit of Native American. And then on my mom’s side, my ancestors are mostly English and Swedish and Welsh. On both sides, I have multiple ancestors who joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints in their countries in Europe and then they immigrated to the United States in the 19th century and walked across the plains with the Mormon pioneers. And they settled on the land of the Shoshone, Paiute, Goshute, and Ute tribes, which they called Utah. My parents were born in Salt Lake City and they got married in Salt Lake City and had me. I was born in Salt Lake City, but when I was four, my parents and I and my baby sister at the time moved to Seattle. And I felt like I lived in a forest in Seattle and I really loved my memories of my early childhood there. And then when I was eight, we moved to a suburb of Denver, Colorado and that’s where I grew up the rest of my life. I graduated from high school there and came back to visit Denver when I was a young adult.

Some more about me, some foundational things, I’m the oldest of five kids in my family. And due to my family circumstances, my mom had a lot of chronic health problems and my dad traveled a lot when I was young, I ended up doing a lot to take care of my younger siblings. And starting from the time they were born, I loved playing with them and taking care of them, but things got hard when I was around age 11. I really love taking care of people, that’s a natural trait, I think, that I come by naturally in my genes. And I really love taking care of people and taking care of my little siblings, but it was also a lot of responsibility for a kid, and so there’s a lot to unpack there. But it made me who I am today in many ways, and my siblings are still my best friends and there’s a lot of love in the family I grew up in. I’m really grateful for that.

After high school, I went to BYU, Brigham Young University. That was the only option I even considered. And I met a guy my very first week of school who I fell in love with, and after our freshman year, we dated and then he went on a church mission to Argentina. And I overlapped with that and went on a mission to Chile. And so we dated for a year but then separated for our missions so we didn’t see each other for three years and just wrote each other letters. And when I got home after those three years, we were still in love and we got married and graduated together from college after getting married.

And then we moved around. We lived in Colorado and then Southern California, where he’s from, and Utah for a bit, and then to Northern California for a long, long time. We had four kids along the way. And I lived a very traditional Mormon woman, Mormon mom life. I loved being home with my kids, I loved my family so much. But at the same time, I also had an undercurrent of deep, deep pain, and discontent, and incessant questions. And that kind of erupted, in slow motion to be honest, but really came to a critical point in a full fledged feminist awakening. And that led to me going back to school for my master’s degree at Stanford while we were living in Northern California. And that in turn led to this podcast. So, I guess that’s the short version of my story, and here I am now.

BL: It’s such a treat to hear a little bit of your backstory because we so often hear about your guests. So it’s nice to be able to hear a little bit of how your path brought you here. And on that same note, we would love to know what brought you into the path of ayahuasca.

AA: Again, here I have to say how vulnerable I feel! Do my guests feel like this? Being in the other chair is so weird. What got me interested in ayahuasca was that I have a really good friend, and we would take walks sometimes and she would talk about her childhood trauma which is different from mine, but she had had a journey. That’s one of the words that people use to describe doing ayahuasca. And it was profoundly healing for her, and I was so interested in it. It didn’t make me want to do it myself, but it kind of planted the seed. And then later, I really like Michael Pollan, whom I quoted in the first episode on peyote, and he wrote a book and had a Netflix series called How to Change Your Mind all about psychedelic plants. And I’ve read a couple of things, and I think maybe we’ll get into it a little bit later in more detail, but those were the seeds that were planted for me that led me to think that maybe I want to have that experience too.

AG: You were hearing your friend’s stories and her experience, and so what about her experience led you to want to seek out more with ayahuasca for yourself personally?

AA: One thing that my friend had shared with me was that she felt that a lot of her trauma was stored not in her conscious mind, but in her body. If you think of the title of that famous book, The Body Keeps the Score, it’s the concept that even if we’re not consciously thinking about things that have happened to us, our bodies store those memories. And I’ve read studies that show that somehow our experiences get recorded even in our DNA, and that can get passed down to our descendants. She had experienced trauma in her childhood so she had sought plant medicine as a way to get at those wounds from earlier in her life and bypass that conscious part of the brain. You know, the part of your brain that reads psychology books and goes to therapy and knows all the right answers and makes a lot of progress. But in some ways, sometimes you can still feel stuck even after making all of that progress. It can feel like there’s a control panel in our brains and it’s locked in a room that we can’t access. Like the conscious part of us doesn’t have access to get at those levers and buttons that we need to push in order to make progress. And so, that’s kind of what my friend had talked to me about, and that’s why she had sought ayahuasca.

And specifically for me, as I started thinking about it, I felt like growing up in patriarchy had severed me from parts of myself. And particularly severed me from my body. I felt like when I was really, really young, I had a very healthy and happy, natural sexuality that got severed by the sex shame of the patriarchal institution that I was raised in. And, you know, there’s all these different ways that I felt severed from my body. If I look back to when I was a little kid, I wasn’t self conscious of my body, but then society’s beauty standards came in and that really sets in hard right around puberty. And being raised in an environment that was so hard especially on women’s bodies, and I particularly was raised in an environment with really disordered eating and extreme fatphobia. And kind of loathing for the body, and fear of sexuality and I had really absorbed that. And I do think that my parents’ generation being raised as they were in the 50s and 60s and 70s got a really, really toxic version of the beauty myth and obsession with weight and thinness. And so the women of my generation who were raised by those women, I was raised in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s, I think that women of my generation who were raised by those women had a really, really hard time with body image, maybe more so in some ways than the generations before us.

And so many times, when my body had communicated with me the way it did when I was little and it was organic and natural and I listened to my body, as I got older and especially around puberty, I started overriding it, ignoring it or saying no. My body would say “I’m hungry, I want to eat,” and I would say no. And all these different ways of neglecting it and also negating the messages that it was telling me. So eventually my body just stopped trusting me. And to be honest, one of the most painful parts is that I ended up being an agent in severing myself. Other people and other institutions taught me what to do and started that process of cutting, but then they handed me the knife and I finished the job myself.

So, now at this stage of my life, knowing that and understanding that… A couple of years ago I went to some really wonderful therapists, and read a bunch of books, and did a lot of work that really did help me. But still, no matter how hard I tried to will myself to feel differently, I felt like I couldn’t reach that part of myself that had been severed anymore. Or if you want to go back to the other analogy, I couldn’t get access to that control panel in the locked room because the thinking part of my brain didn’t have connection to that, if you want to call it trauma or those past experiences, the past training that was stored not in the thinking part of my brain, but in my cells somehow, in my actual body. So those were the things that I was struggling with that led me to think that maybe I would seek plant medicine as part of healing or a solution.

BL: I’m curious what your emotional landscape was like as you were thinking about doing ayahuasca, and what were your feelings about ayahuasca before going into it?

AA: Totally nervous. And I was not only nervous because it was a new experience, it’s also a different identity to do a mind altering drug. I know they don’t call them drugs, but a substance that alters your mind. I don’t even drink coffee. I’ve never had alcohol before. I still haven’t and I never will. As an LDS person, that’s really outside of my experience in a way that was very hard for me to get over. To make that decision that I would do that meant that I was a different person in some ways. And so that was a big barrier. I’ve also seen addiction in my life close up and it terrifies me. I don’t drink Diet Coke. I don’t do anything that might make me need any substance. I don’t judge people who drink Diet Coke, by the way, or drink alcohol. I’m just saying that for me, from my personal experience, I was like, “nope.”

But once I started reading more, again Michael Pollan’s books, and talking to people and hearing that it’s plant medicine, and that it’s called that for a reason. It’s not addictive and it’s more of an experience and more of a therapy and a journey where you learn things. And so I had to make that shift to do that, because I am not the kind of person who seeks a party drug or something. I don’t seek that at all. In fact, it’s very scary and threatening to my identity for me. So anyway, I was super nervous. And then as the time was getting closer, I just wanted to back out. It just felt so scary.

sometimes you can still feel stuck even after making all of that progress

I will say also, I was nervous about cultural appropriation. That was something that I needed to do a lot of reading and thinking about, too. Because even though, I mean, I have Native American ancestors, and that’s really sacred to me, but that’s something that I keep very personal. And I know the Elizabeth Warren phenomenon, and I’ve even heard other people talking about it, like checking “Native American” on scholarship applications when they have lived as a white person their whole life. Taking advantage of that, I think, is morally repugnant, to claim that when you haven’t lived that experience. I was really nervous. I also wanted to make sure I was doing it the right way that wasn’t going to take in an inappropriate way. So I was worried about cultural appropriation too and whether it was okay for me to even do it in the first place. But I got to a point once I talked to the people there and was kind of exploring that I felt like it was appropriate and it would be okay. So, we signed up. My husband and I signed up together.

BL: How long was that process for you, roughly? From when you started thinking about it to working through all of that emotional shifting in the idea like “this changes my identity a little bit” and “I’m the kind of person who never has done this.” How long was that for you to be able to get your mental landscape okay with moving forward with plans?

AA: Like a year, probably. And I wasn’t thinking about it constantly, but when it came up I was like, hmm, and then it kind of gathered more momentum. And once I talked to the people, I went to the same organization where my friend had done it, which was in California. And just because of their scheduling, they said they didn’t have any openings when it would work for me, so I could go to Washington. So there was a lot of time where I was like, I would actually have to buy a flight. I would have to go to Washington. You know what I mean? So it gave me time to really think about it. But probably a period of months after that, once the ball got rolling.

BL: Yeah, it takes some time to really sit with some of those big changes and see how you really think about them. And then shift some of your perspective on that and take some time to sit with that.

AG: It is interesting for those who were raised in a conservative religion or high-demand religion, that oftentimes they will go through really large scale ceremonies or rituals that represent a new birth or shedding the old self, or taking on a new persona. Whether that’s baptism, or for LDS people, going through the temple or going on a mission. And then to be going through them in midlife and think, you know, “Oh yeah, I’ve been through a baptism,” and then all of a sudden be taking that on in midlife, it feels really big. It’s a loss in some ways. You’re letting go. It’s a true baptism or resurrection in a way of really letting go. Like a trapeze artist where you have to let go of the one bar and before you’ve reached the other one, there’s that moment of full letting go. And, that’s not insubstantial. That’s a big decision, a big journey. So it’s really beautiful to hear and I applaud you for it.

AA: Mmm, thanks.

AG: So, what was the process? Once you decided you were going to go forward with this, you’ve spoken with the people who eventually become your guides, what did you have to do in order to get there? You talked about how you hadn’t ever even had any alcohol or that you don’t drink coffee or Diet Coke. How did you go from that to being able to take this plant medicine?

AA: With no preparation, it was a cliff jump. I just cannonballed. Haha! And actually that is kind of true. I mean, emotionally and mentally, I gave it a lot of thought and I read, like I said. But in terms of doing any somatic stuff, like you talked about in your episode with peyote, doing the vitamins or doing the cold plunges… Zero. I didn’t do any bodily preparation, which actually turned out to be fine. But we joined the Church, that’s what they asked us to do, and we did that with great respect and gratitude that they were open to allowing us to do that. I mean, it’s not inexpensive, I will mention that. It was a two-day thing, and it includes paying the practitioner, you know, the guide, and it pays for the medicine itself and for the whole experience. This is Tlawil, who did the episode right before this. This is her job. And so there was some expense there, so we paid for the experience. And then we bought tickets to Seattle and flew to Seattle. And I grew up in Seattle for a few years when I was little, like I said, and looking down out of the window was huge Mount Rainier through the clouds. So we flew to Seattle and then drove, and Tlawil’s home is right by Mount Rainier. But it was funny because when we were introducing ourselves to Tlawil and to the other people in the group, they were like, “Wait, come again? This is your first experience not only with plant medicine, but–” and we’re like, yeah, you know, Mormonism and stuff. I’m like, “I don’t take NyQuil. I’m new to this!” And they could not believe it and it was quite funny. So that was the preparation, I guess.

AG: Like I talked about with that trapeze, it’s a leap of faith, but it sounds like you made quite the leap. And I think that there is a beauty to that, that you fully let go and surrendered to that experience. And I also love the imagery of your inner Little Amy that you took with you on that airplane back to Seattle to do this healing as an adult. I think that is such a great circle. That is really neat.

BL: We talk a lot in the plant medicine space about mindset and setting, set and setting, that comes up in a lot of Michael Pollan’s work and stuff like that. I am curious what the setting was like for this experience. What was the space like? How many people were there? Where was it held? What did the container look like for the group?

AA: So it was winter, it was January, and by Mount Rainier there’s tons of snow but it’s also green. Tlawil and her partner live out in the woods. And I’ve read that a lot of plant medicine retreats, particularly ayahuasca, take place in Central America or South America, and sometimes in very plush, luxury resorts. And that was not this. They live in a really modest home in the woods, and it’s beautiful. There’s a natural river running through, and that’s different for me, having grown up in Colorado where everything freezes in the winter and it’s dead. And in Washington in the Northwest, Alicia, you’re from Washington, right? You know this.

AG: I am. I’m loving every detail about this.

AA: Yes, right? I mean, you get snow, but there’s always green. So there’s life and the frozen death at the same time. So that was the visual setting, water rushing among snow and beautiful trees. So we’re driving there and I’m feeling sick to my stomach, I’m so nervous. And my husband was there too, and he’s also squeaky-clean Mormon his whole life, never done anything either. And so we got to the house and I will always remember sitting in the car and us just looking at each other like, “What have we done? Why are we here?” We were so scared. And we’re like, okay, let’s do this.

And we walked in and it was very cozy. It’s a humble home but it was spacious inside, and they had cleared a whole room. And we walked in and there were mats for each person, I would say there were maybe a total of seven people, Erik and I and then maybe five other people. Mats and bowls to purge into during the ceremony, and then there was a wood burning stove in the middle of the room. And it was kind of dark and just very cozy, with lots of Indigenous art everywhere. Tlawil is Colombian and Mexican and that was reflected in the art. And then there was quite a bit of time that Tlawil facilitated for us getting to know each other and for people talking about why they were there, sitting in a circle and saying their intentions. And everybody was different and everybody was coming to it quite vulnerable, even though they were all way more experienced than Erik and I were. And we were all seeking something deep.

BL: Coming into the experience with such little, if any, experience with substances, were you nervous to take a substance in the presence of other people? Was that something that made you apprehensive or were you able to just let that flow?

AA: No, I was nervous. And in the presence of other people is interesting because I was just reading my notes that I wrote afterwards, they’re right here and there’s a big water stain on them, but this is what I wrote right afterwards. And I had forgotten that one thing I wrote was that even as I was first beginning, once I had drunk the tea at the beginning, I was still conscious of “Am I acting weird? Do I look weird?” And I was talking to myself like, “Oh my gosh, let go, Amy, let it go.” So yeah, I guess I’d forgotten that part. Plus, nobody likes throwing up. Nobody likes throwing up in front of people.

BL: Or hearing other people throw up! All of it is a little bit uncomfortable. And it’s an interesting part of surrendering where, just like you were saying that you are conscious of some of those things to a certain point, and then you really do have to surrender to that to get into the experience or to the other side. But I think that’s a pretty common apprehension when you’re going to be in the presence of other people. That really brings up some of our awareness of how we present all the time.

AA: It wasn’t a big deal, I guess, but that was definitely there, for sure.

AG: Once you arrived and you’ve taken in the space, gotten your lay of the land, what did you do once you got there? Was there a bit of time before you sat with the medicine, or like you mentioned, you sat and spoke with people?

AA: Yeah.

AG: What did you do?

AA: We came in and met Tlawil and her partner, but other people hadn’t arrived yet. And I had just recorded my episode on the book Women Who Run With the Wolves with Bergen Hyde, and I hadn’t read the whole book at that point but I had that on my mind. I mean, prior to arriving at the house, I was like, I want to read more of that book. And when we walked in, I was walking around the house by myself, just kind of acquainting myself with the space. And I felt myself walk into this room and I looked and a copy of Women Who Run With the Wolves was right there on the table, which just felt like a really lovely introduction. I try not to attribute anything to some cosmic plan or anything, probably just from a lifetime of processing what that means and doesn’t mean for me, and I tend to be a little more skeptical now. But I took that as a lovely thing to happen. So I took it over to the couch and read that.

And then as other people arrived was when we did introductions and intentions sitting in a circle. And then Tlawil did some beautiful prayers and blessings from her tradition, from her family growing up that come from both her mother’s and her father’s side of the family. They used tobacco, tobacco is often used in ceremony. Sometimes it’s smoked. I wouldn’t have felt comfortable doing that, but some inhaled the tobacco in a circle. I wasn’t prepared for that. She also had a few other medicines but I was like, “I was only prepared for the one, so I’m just going to watch.” And everybody did different things, but some blessings that were really centering and really powerful for me to be in the presence of a woman who was leading that. And in that sacred, spiritual space to be looking to a woman as a spiritual leader was profound for me because of the background that I come from.

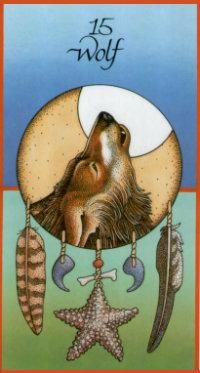

And then the most meaningful part that really struck me, and again, I tend to be quite skeptical now. So I’m just going to leave it and I’ll tell you what happened, and dear listeners and Bre and Alicia, you can come to whatever conclusions you like. So Tlawil has some, they’re like tarot cards, but they’re animal cards that come from kind of an amalgam of different Native American traditions. And she asked us to choose a card, and again, I’m sitting there with an open heart and an open mind, kind of like how I always feel when I go to Jewish friends’ bat mitzvahs or whatever. I love comparative religion and I respect it deeply, but I also am very skeptical. And so, in terms of what does this mean? I don’t know. And I don’t think anybody knows! But I had an open heart. And Erik, by the way, is such a skeptic. He was over there like, oh my goodness, we’re drawing cards, are you going to tell my fortune? So Tlawil had cards, and everyone would take a card, and then afterwards, she had a book – here’s the book, because we got it afterwards – and the card Erik drew was exactly his intention coming to the ceremony. It was exactly who he is and why he was there. So I just watched his eyes get big. It was crazy.

And I’m going to read the one that I drew. So I drew, in all of the cards, there are like 52 animals. Rabbit, turkey, ant, weasel, grouse, horse, lizard, antelope, frog, swan, dolphin. So many animals. I chose wolf. After I just found Women Who Run With the Wolves, I was like, “What is happening?” So I drew the wolf and was already like, whoa, that’s crazy. And keep in mind that this was when I was at the end of recording season one of the podcast, this huge educational project where I was choosing to share everything I was learning with the world, and people know about that process, I guess. So I drew the wolf and then Tlawil handed me the book and it says this: “Wolf. Teacher. Wolf is the pathfinder, the forerunner of new ideas who returns to the clan to teach and share medicine. As you feel Wolf coming alive within you, you may wish to share your knowledge by writing or lecturing on information that will help others better understand their uniqueness or path in life. It is in the sharing of great truths that the consciousness of humanity will attain new heights. Look for teachings no matter where you are. Wolf would not come to you unless you requested the appearance of the tribe’s great teacher.” It makes me a little emotional to read it. So that is what happened before ayahuasca. And it still means a lot to me.

AG: And understandably, that experience is so powerful. And one thing for me after deconstructing so many beliefs is to actually remove belief or interpretation from the equation of experience. That what you experience is powerful and mysterious and awe-inducing and moving, without knowing or interpreting being any part of that equation. In fact, that might even detract from your experience which is clearly so moving and powerful even now, and I love that.

BL: Thank you for sharing that reading with us, too. That is pretty intriguing to pull that card right at that time with the podcast starting and with your intentions and what you were seeking going in. We’ve talked a little bit about the external environment, and how you walked into ayahuasca and found yourself there, what the setting was like. I’m curious what the actual journey was like. What was the internal experience?

AA: Tlawil had brewed the ayahuasca with the leaves of the plant and made kind of a dark brown tea. And we all drank it and she administered different amounts to different people and she gave me a really small amount based on size and also because I had no previous experience. It was kind of bitter, but it was fine, it was just a little cup. And then we just stood by the fire, this was at about 11 pm, and we waited to see what would happen. And like I said, we each had a mat and blankets that she had set up, and Erik and I had mats next to each other. And I expected to be sick, to throw up and purge, and like you talked about with peyote, “get well.” And I was not excited for that, but I just thought it’s part of the process so I get it.

And I felt myself getting kind of warm and I felt my hands getting heavy. So I was like, okay, I’ll go lie down. And I lay down on the mat and I was just looking up at the ceiling. Also, I go to bed really early. I’m a very strict sleeper. I go to bed at 11, and my sleep is really important to me. So I also was like, “Am I just going to fall asleep and then have weird dreams? What’s going to happen?” Anyway, I was getting tired by that point. But I looked up at the white ceiling above me and I started noticing colors and shapes starting, and then it turned into kind of like a kaleidoscope. And at first I saw it with my real eyes on the ceiling, but it was kind of pop art-y, just really vivid colors like candy and cats and ice cream cones, and I saw that for a while. And Tlawil had said, like she talked about in her episode, that Mama is sentient. There is a spirit that is in the plant that will be our guide, and you can talk to her. And so I was lying there and I was like, “Mama Aya, this is not why I’m here. I’m not here to do a party drug and see kaleidoscopes of cats and candy.” I didn’t like it. Then I got the feeling like, “Just be patient. Just go with it.” And then I closed my eyes and I was still seeing them. So mostly I had my eyes closed. Then it turned into skulls. Lots of skulls. And snakes. Lots of snakes. And I do not like snakes. But it was fine, and I was open to it. It felt very much like Day of the Dead, like you might see in Mexican art. But it was still kaleidoscope-y.

there is a spirit that is in the plant that will be our guide

And then I started having the sensation of going down. My eyes were closed, and then at some point I was not aware of my body anymore, and I was sinking down, down, down into the dark. And I had a bunch of visions and experiences, but would always return skulls. And I actually don’t remember what a lot of them were. And I remember being aware, like “Oh no I’m not going to remember this! Can I write it down?” And then having the feeling that I would have to use my hand and find a pen, and there’s no way I can move my body at this point. So I was like, oh well, I won’t remember a lot and that’s okay. But I guess, to break it down into the main themes, when I was down there I would have visions and then I would realize I wasn’t breathing so I would panic and come up. Almost like a diver swimming up to the surface and I’d open my eyes and be like, oh my gosh, I wasn’t breathing. Breathe. And then I would sink back down and have another something visual, but skulls and snakes. And then, oh no, I’m not breathing. Up, up, up and gasp and oh no. And I was very scared that I was going to stop breathing when I was down there. And I did that for a long time, up and down, up and down, panicking that I would forget to breathe.

And then two things happened when I finally came up. It was like I was on the surface of the Earth and there was a person sitting there on a chair. And I was in a deep, deep cave, like an opening into the Earth and I knew I had been down deep. And when I came up and gasped for breath and I looked at the person I was like, “I’m going to stop breathing.” And he said, “I won’t let her die.” And I knew, somehow, that this person was a representation of part of my body. And in retrospect, here’s my analysis, that it was somehow the part of my brain that watches over all of the automatic functions of the body, all of the involuntary stuff. And he was so gentle, he was like, I watch over you every minute while you’re sleeping, while you’re deep doing your work and six hours passes and you’re deep in mental work. I keep you breathing the whole time. And he said, “I won’t let her die.” And “her” was interesting, it wasn’t “you”. It was like, “I won’t let her die. I’ve got you. You don’t have to worry. You don’t have to keep coming up here.” And this person was a man, it was a masculine presence that was like, “I’m here all the time watching over you.” So I went back down and tried to trust.

And at that point, I did keep coming up and physically breathing, getting scared, but then going back down. And then suddenly it transformed and I came up and I had this peaceful feeling, and it’s going to sound weird, but the thought that came to me was, “Oh, this is fine. This is just like when I was a whale.” And again, it didn’t feel weird in the moment, and I realize how that sounds now. It was just this knowledge of “We were whales. I’ve done this before.” And then I was okay. Once I was like, “I’ll just keep breathing when I need to breathe.” That was really special. And obviously the whales were so meaningful to me, because we literally are connected to each other in some weird way. But then also just the katabasis, which I talked about in the intro. This deep, deep journey down and then coming up and having someone keeping me safe while I did that journey was just so special. And I loved that it was a masculine presence for me. Whatever that is in my brain, whatever that is in my body, I’ve made friends with that guy. I’ll talk about that a bit later.

But one other thing about the experience was that pretty soon I lost almost all my language. I guess I must have been operating in a part of my brain that isn’t the word part. And that was really unnerving for me because I live in words every single day, all day. I am reading, and writing, and speaking. I’m a super verbal person and my words went almost all the way offline after a little while. The only words I would hear were, like sometimes I would hear “Breathe” and I’d go up and gasp. And at that point too, that’s when I would open my eyes and be like, “Oh yeah, I have a body. I’m in a house.” And I would reach out to feel Erik and I’d feel his arm and I’d be like, okay, back down. And then I’d go back down.

BL: Could you say a little bit about how you lost your words? Were you just seeing images and pictures or was it totally outside of human cognitive understanding?

AA: No, no, only words were gone. Again, it was weird, but it was also familiar. And in retrospect, I’m like, oh yeah, because babies. I’ve been a baby that didn’t have language yet, and you actually take in a ton of meaning, and it almost just felt like you could communicate conceptually. And I’ll talk about that in a second, about people that I had conversations with without words. Almost like you were in a video game, you could direct your attention towards something and communicate your question without words and they could communicate concepts too. But honestly, it was a relief. Because I think, again, it’s my greatest strength and it’s my greatest weakness. And it makes me crazy, the chatter and the self-doubt that I experience. And also, like I said, the body image stuff, the way the negativity that my brain has picked up through my life, that verbal part of my brain directs toward my body. I’ll talk about that in a minute too, but it was scary a little bit. Who am I without words? And also, oh, what a rest. What a rest to not have that constant chatter, you know what I mean?

BL: That is so interesting.

AG: That is so beautiful.

AA: But it did get scary. Well, actually, I’ll read this. This is what I wrote the next morning: “I would try to form words, but just feel a blank space and no words would come. This was scary at first, but it came to be a huge relief as I realized that that tiny, tiny part of me, of conscious thought, is where I live almost 100 percent of the time. I’m imbalanced. My verbal, analytical, critical brain is doing such a great job writing my thesis. But it also tortures me all day, every day with, ‘Did that sound smart enough?’ Is she–” and again, I had distance from myself, “Does she seem good? Did that hurt their feelings? Are they mad? Is that what he wants? Is that young enough? Is she skinny enough? Is she smart enough? Is she wise enough?” And I wrote that all through these years, interestingly, I have these protective barriers and I’m always thinking about there’s me, and everybody goes through this, but how is she being perceived?

And then I talk about later, actually, I suddenly felt like I was so, so, so deep down there and I suddenly remembered that I had kids. And up on the surface, there was a person there who was a mother and I couldn’t remember my kids’ names. And that was the part where I really got scared. Because I was picturing them in my mind and directing my energy toward them, but “oh no, what if I can’t come up out of here, and what if I can’t find them?” Because I felt really far from them. And then I was directing or exerting, trying to remember their names, and I couldn’t remember their names. And obviously because I’m crying now too, that really, really scared me. And then I felt Mama Aya, whatever that is, without words, just calm me and tell me “They’re fine, it’s okay. You’re only going to be here for a little while longer. Let go. I have things I need to show you. It’s okay.” And then I was able to be okay, but it was really weird to not be able to remember my kids’ names.

There were two main visions that I do want to share and I’ve thought about if I should share this, and I will. As I went down, down, down deep, and again, I just kept seeing skulls and visual things. I was like, “What does this mean?” And I kept asking Mama Aya, “What are you trying to teach me? I really want to connect with my body, Mama Aya. I really want to integrate.” Like directing those concepts toward her and having her be like, “I know, I got it. Just wait.” And so finally, we went down to where I was seeing, again it was very visual, it looked like roots, like dark browns and purples. And I was looking around, and then I became aware, and again at this point it’s hard to describe it because I didn’t have access to words and I’m using words to tell a story in this other weird little part of my brain. But anyway, I became aware that I was in my body. And I started to see different systems of my body, the digestive system, and sexual organs, but from the inside, and nervous system, and skeleton, and muscles and everything.

And it was like a universe in there, and I became aware that all of the systems communicated with each other. They all knew each other like it was a huge family. All of the systems knew each other, communicated with each other, loved each other, and loved me. It was full of love in there. And it was mind-blowingly complex, and everybody was working so hard doing their job to keep her alive and functioning. And I didn’t even know that. All day long doing that stuff. And I have really struggled with body image, and I know a lot of people do. But I did surgery after I had my kids, because the weight gain of having babies was so distressing to me, I think mostly because of the way I was raised, but I just couldn’t handle it. So I did one of the mommy makeover surgeries or whatever, to just get your body back. And so I did that years and years ago and I felt inside the body like I relived what that felt like from their perspective.

And what I realized was I thought that because my conscious verbal brain had been put to sleep through anesthesia, I didn’t remember the surgery. I didn’t remember the surgery. But they did, my body did. And I experienced the ripping open and the sucking out of getting rid of fat from after the baby. They thought they were dying. The systems in my body were in full panic. It was like a war scene from a movie where they’re sending soldiers to fight infection and they’re like, what is happening? It’s as if the sky just opened up and aliens started pouring down into our world. And my body was terrified and I relived that experience from inside it. And I was devastated and sobbing and sobbing and sobbing. And it turned out that because I still had to come up to breathe sometimes, I would come up to breathe and I was like, “Oh, I have hands.” And I’d go like this and I’d feel that my body was sobbing, there were tears in my ears and pouring onto the pillow. Then I’d go back down and just relive it for a long time. And I was down there saying, “I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry I did that to you. I didn’t know. I didn’t know that that’s what I was doing to you. I didn’t know that you would hold on to it and that you would still be dealing with the trauma.”

And then I relived lots of other things that have happened that have been traumatic for me in my life that they were still having a hard time with in there. And so I grieved, I grieved with my body about all of the things that had happened to it. Some of which I had subjected it to. And then I also grieved because I could also see the way that I had continued to harm myself every time I allowed that verbal part that I think of as me, to direct unkindness toward whatever part it is when I look in the mirror and I see wrinkles, or I see gray hair, or I see fat here or there, and I direct this unkindness to these systems that are literally working all day, every day, and all night, every night because they love me. And I just had a long period of grief and apologizing.

And then that’s when I felt, and again I was in a world without words, but I felt the word come to my mind from Mama Aya that just said “heal.” And it was not a voice that sounded like mine and it felt so powerful and golden and full of light. And I felt my own hands, my real hands, make a triangle and go to my womb. And I put my own hands in this triangle on my pelvis and I just felt this word “heal” and gold light flooding in. And I was even aware down there, and the context that I have for that is like in the LDS church like a priesthood blessing, but it was my own hands. And it was my own, it’s just silly to think, I was going to say authority, like whose authority, it was the Earth and Mama Aya that said “heal.” And as I would go on to different experiences, I would find that if my hands had fallen to my sides it was like Mama Aya or like this presence was coming and would take my hands and put them back on like “hold on, you forgot, heal” and the triangle of power would come back. And that kept happening for the whole rest of the journey. So that was a big deal. And then I would cry and cry and cry and apologize some more and then go through something else. And then I’d come back, heal, and cry and cry and cry, and grieve and grieve and grieve, and heal. So that was the first one.

I grieved with my body about all of the things that had happened to it. Some of which I had subjected it to.

Then the second big vision was that I was going over a landscape. And I then became aware that it was like she was guiding me and saying “We’re going to see your ancestors.” And I was like, “We’re going to Scotland!” And I was so happy because I feel very, very connected to my Scottish ancestors, actually. And that was really meaningful to me. But as we got closer I became aware that we weren’t in Scotland and I became aware that we were in North America. And it was like I was zooming down and seeing where we were and I knew I was going to see ancestors, and then we were in North America and I realized we were going to see my Native American ancestors. And I tried to pull up from it and I said “No, no, no, no, this isn’t mine.” Still, even in that state, I was like “That’s not appropriate. I’m not here to have a ‘Native American experience’ or whatever. That’s not mine.” And I kind of redirected, I was like, “No, take me to Scotland.” I was trying to go east. I’m like, “No, no, it’s over there.” And I just felt, it was kind of like the concept was “We can go to Scotland next time if you want, but right now, this is who you need to meet.”

So we went down and there was, again, I’m trying to think of how the words were. And at this point it wasn’t like I saw battle scenes or anything like that. It wasn’t played out visually, I just had knowledge come to me that I was conversing with the last ancestor. And it reminded me of when you were talking, Alicia, about your ancestor who ended up marrying into the white community. And for me, that was the person that I was communing with. And again, it was grief. Because I realized for that person that she was trying to connect with me, I’m like, “No, no, it’s not appropriate.” She said, “Listen, if you don’t know about me, no one knows about me. My story’s lost.” And she was aware that the language of her youth would not be spoken by her descendants. And the culture and everything about her entire world was disappearing into whiteness and into this colony from across the world. And she wanted me to know that she’s in me.

And my hands were on my pelvis but I felt this force bring my hands up to my face. And again, I was like bawling. But as I’m wiping tears, I felt this awareness that she’s like, “This is where you look like me. That’s why you’ve been seeing skulls. It’s because you have my face. This part of your face is from me. And I want you to know that.” And again, it was like being inside my body and I was able to be inside my DNA somehow and realize, and again, this is provable that we do inherit features from our ancestors. And she said “You do look like me. Your face looks like me.” And I thought, “Maybe I’ll have a descendant someday that will also look like her.” And that was a really powerful experience, too. She said “I’m with you, and if you don’t know about me then I am lost.” So that was really special and beautiful.

AG: Well, I have so many notes because you have said so many beautiful things that I would love to either look up or talk to you more about. One thing that I do think is interesting is that with plant medicine, we often come with an intention, but we don’t get to pick the way we get there. And so often, you are in the middle of it and you’re like, “Wait, no, no, no, this isn’t what I wanted.” And that’s where the trust and the surrender comes in. Because you asked for a destination, but they’re not just giving you a destination. You’re going on a journey to get there. And what I see in what you’re talking about is you stepping up to become the authority for yourself, in your own body, in your own healing. And when we were taught at such a young age, whether you were raised in patriarchy to look to men for those answers, or in a high-demand religion to look specifically to a man with specific authority over you for those answers, you were getting connected to yourself directly and becoming the authority for yourself. And I think that is exactly what you asked for. Maybe it didn’t come exactly as you expected, but it is very empowering and beautiful to listen to those stories.

And also something that’s coming to my mind as you’re talking is that we often think of grief as a destination. I’m in grief right now. Or healing as a destination. Oh, now I’m healed. I passed that. But both grief and healing are motion. Grief is working through all of that trauma and it has to stay in motion in order for it to clear and let everything else flow out so that you can make space for the healing and the joy. And you don’t ever really arrive at healing. You just learn to walk with healing. You learn to walk with grief. You learn to walk with all of these different experiences. And that is so, so powerful.

BL: It really is so interesting. Alicia says that we don’t know the route or some of the information that we’ll receive. And it is so interesting to see how the process took you through this idea that we are ancient, that our cells are ancient, that we carry this DNA that we can quantifiably even track at this point. And that you had come in with this idea to reconnect with your body that you felt like you’d been severed from. And then you did that work for yourself and saw that your body is your friend and that your body is taking care of you. And that even when the verbal part of your mind can be so unkind to yourself, that the body is taking care of you.

But then also with the work of that last ancestor, that she had also been severed and needed to be reconnected. And so that idea that even within your own body, you wanted to connect to your body. And through that, you also connected this last standing female ancestor who also reconnected to your story. It’s just so fascinating the way that our minds unfold some of this healing. And seeing things in a new way that when we come offline from our systems like your verbal processing, that you’re able to evaluate something. Even if we talk about today, like you were saying, you’re using words to explain this experience that doesn’t quite fit into words, but it lets us contemplate what our bodies even are, what our ancestors even are, that we are all of that together. And you don’t even have to believe any of that, that is just how evolution and DNA works. It’s just fascinating. Thank you for being so open to sharing that with us. It’s a beautiful experience.

AA: Thanks. I hadn’t thought of it that way either of my ancestor being severed and that that was part of the integration too, until you said that. Thanks. Thank you both.

AG: I’m curious how, going forward, was that experience of having your verbal processing kind of offline and just being with your inner knowing, how has that looked going forward? Has that integrated into your life at all or changed anything for you? As well as meeting this ancestor. Maybe the way that you view yourself or the way you interact with the world or with yourself. Has that changed anything?

AA: Mm-hmm. Yeah, it has. I think it was so interesting in a lot of ways, but one thing that was so interesting was to have that guard person that’s keeping watch over all of the processes and making sure I’m okay. That he said, “I’m watching over her. She’s okay. I’m not going to let her die.” Even to me, that I am the self, like why didn’t he refer to me as “you”? And again, I don’t know, I don’t have any new dogma that I believe in now, but that connection to ancestors and all the way back to evolutionary ancestors, it did make me think that I see why people believe in reincarnation. There’s a soul, there’s some little spark of a soul that is having all of these experiences and we’re all connected. And what I think of as me is not. And so it puts that in perspective, that I’m having this experience and I’m learning here during this life and this is all I know. But it gave me more of a perspective not to take that so seriously, too. And we know this from reading anything about Buddhism. That’s one of the whole points of Buddhism, is to have some more detachment and just look at the monkey mind with benevolence and compassion. Like, “Oh, you’re having so many thoughts in there!”

But there’s something that is what I think of as me, is this eternal thing. And so with that, I do have more detachment with those thoughts. And the biggest takeaway is that when I notice those thoughts being unkind, I feel like I remember that guy on the chair sitting there. I love her. And I remember everything inside my body that was just like, “We love each other, we will protect each other. We will send in your immune system if you get cut, we will protect each other, and we love you up there!” And so if I hear that chattery part of me being mean to them, I’m like, “Oh no, you do not talk to her like that.” I feel reverence for my toes. I feel reverence for my liver and my lungs. And I check in with them. For years, when I would wake up in the morning, the very first conscious thought I would have is checking and assessing my body to see if it was basically skinny enough, you know what I mean? That’s what eating disorders do to you. “Am I worthy?” basically is what I’m checking. Feeling my body and then having unkind thoughts like, “What did I eat yesterday?” And I am so done with that.

And I had started making progress on that anyway, but now I wake up and I feel in control. I realize, I’m like, “I know what you do in there.” And I wake up, and I use that verbal part of myself to greet my body and say, “Hi everybody!” It’s like I’m a kid, but I’m like, “Hi, I love you! I love you, arms. I love you, fingernails.” I will greet my body and say, “How’s everybody doing? I see you. Thank you, and I love you.” And if I catch those old habits, I nip them in right in the bud. “You do not talk to her like that.” So that’s one of the biggest changes that I’m really, really, really grateful for.

I’m having this experience and I’m learning here during this life

AG: What a powerful, actionable takeaway. And you talked about feeling severed from yourself and from your body going into this. And again, you never know how you’re going to get there, so it was this journey that was at times confusing, you couldn’t remember your children’s names, you know. But I think what you kept having to come back to in your body was trust. And your body was teaching you to trust yourself after a lifetime of being taught to distrust yourself.

AA: Yeah, exactly.

AG: And so to be able to come out of it with so much love and gratitude is all you could ask for it. It’s so powerful, even just hearing your voice and your words. It’s making me emotional to be able to reconnect. And I think it also speaks to the power within us that you can have a lifetime of an entire global system set up for you to be separated from yourself and to go have this one experience and you are able to reconnect. I think it speaks to the power of self and the power of, again, I know I keep coming back to this, but that love as a force, that love heals. That it is not just an emotion. I think that is just so wonderful to hear your whole story.

AA: Thanks, Alicia.

AG: Do you have any other takeaways you want to share from your experience?

AA: Well, I was going to say, one thing that we talked about before that I was going to mention on that topic of trusting the body and the history of like, when it says it needs food being like, “Shush, no you don’t.” And it wants sex with this person that you love and trust but “No you don’t, you don’t get that.” And then it’s saying “No, I don’t want this sexual experience” but “No, you have to do that.” Or “I don’t want to do that.” That’s, I think, what severed the trust too. And so after this experience of going “No, I listened to you and it’s going to take a long time to re-earn your trust.” Putting my body through that surgery that didn’t even need to happen. And I should say here too that if you need to have a surgery, I’m grateful I had a C-section to save my baby’s life and save my life. Sometimes you need traditional medicine, you need surgery, so that’s not the point of this. But to subject my body to that violence and to all the unkind thoughts, it’s a process of trusting the conscious me, which is the one that makes the decisions for it.

And so one thing that came up with me and you two, one thing that we didn’t mention is that Alicia, you so beautifully and generously invited me to participate in the peyote ceremony that we talked about. And at the time I was so excited for it and I was preparing for it. And a couple of weeks beforehand I got sick and I just kept waiting. Well, obviously I’ll feel better two weeks away or whatever. And I got worse and worse and worse. Then I got better briefly and we met and I was like, “Oh no, I’m getting better. I’m just coughing sometimes.” And the day before the peyote ceremony, which I’d been so excited for, I kind of nosedived again. And I really wanted to participate for me, and I really did not want to let you two down. I’m a person who keeps commitments. If I say I’m going to do something, I do it. Even if I don’t feel well. But I knew that this ceremony was going to involve many hours in an enclosed space with fire, smoke, and that I would probably be throwing up.

Anyway, the behind the scenes conversation that was happening as I was texting with both of you that I was still really sick, and I was deciding whether to do it, I just went into my closet and what I do now, if I’m thinking “Is this going to be good for my body?” I check in with whoever that person is who sits up there in my brain and oversees all the stuff. And I had a conversation. I said, “Hey, how’s it going in there?” We have conversations now. Whatever that was, he was like “We’re taking every resource, every bit of energy to fight whatever it is that’s in here attacking your lungs. This is going to be really hard. This is going to make it really hard for us.” I wouldn’t die. It’s like, “She won’t die, but it would not be a good idea. This is really going to be bad for her.” And I was like, “Are you sure? Because I really want to do this.” And he’s like, “It’s really going to be hard on her. I would prefer that you don’t do this.” And that’s when I texted you and said I didn’t think it was a good idea.

And then I think it was two weeks later, I still wasn’t better, and I was diagnosed with pneumonia. I didn’t know at the time, but I mean, it is applicable in my everyday life. That I check in. “How’s she doing in there? Give me the report.” And it’s like they have a little meeting around a desk, a little conference, like, “How are you doing? And how are you doing? And how are you doing? Okay, she’s okay.” Anyway, that was kind of a funny story. But that was one of the takeaways. And then I was reflecting on this this morning, that I need to check in with my kids more often about their internal dialogue with their bodies. Because I think they absorb things from the culture that they don’t realize they’re absorbing, and they certainly don’t talk about it with anyone, and then it gets entrenched. And then they find themselves in their 20s, 30s, 40s with all of these repeated narratives that are causing real harm inside of them. So just this morning I was thinking, I’ve got to check in with my kids again about that. Are you being kind in there? Those are my big ones, I think.

BL: It’s also interesting, the experience walking towards peyote, that that was an opportunity for you to use the lessons that you had learned with Mama Aya in a very, what felt like a high stake moment of, can you be on your own side? Are you doing the healing work to be on your own side and to not continue to sacrifice yourself to the external things around you? And there are times that we have to do things we don’t want to do, but that was a really brave thing to check in with your body and realize it was not the right thing. And to choose yourself rather than some of these commitments, because that is a really hard thing for you because you made a commitment to people. And it’s interesting that even without sitting with peyote, it’s part of your peyote experience, integrating with that Mama Aya experience of checking in with my body. I’m on my body’s side. I don’t betray her anymore on behalf of anything else. That is where my root source is now, is how is she doing? That’s a pretty profound and beautiful way to walk forward in the world.

And that’s one thing I really love about plant medicine all through history was this idea that you would walk towards plant medicine and not only would you heal yourself, but that you would go back out into your community and into your families and help heal them with what you had learned, which is what you’re saying with your daughters. To talk to them about their internal worlds, that they don’t even need to sit with plant medicine to have the benefits and the lessons that you learned from the plant medicine. And so not everybody will have the opportunity to sit with medicine, but as we learn these lessons and then come back and incorporate them and help other people be kinder to themselves, to see the love within us and the love around us, and to integrate back into our bodies and to check in with with whether you are on your own side. Are you on your body’s side? That it doesn’t have to be “No, you can’t have that, you can’t do this.” And as we become gentler in our minds we become gentler to our bodies, and we become gentler to the communities around us. And we heal some of those lessons that we’ve been steeped in in our community, that there’s one way for us to be and often it’s not very kind in the internal world. So, thank you for connecting all those pieces in that story. It’s beautiful to hear the whole arc.

AA: Thanks, Bre. I’m so grateful that you said that because that was one of the things I didn’t want to forget to say. Like you said, you don’t need to fly to a different state and pay for some sort of retreat to learn these things. Ultimately, like you said, it is just grounding you in your own wisdom. And that can be done, I think most helpfully probably through meditation. But just making the space to be honest with ourselves and how we talk to ourselves and calming the monkey mind, and creating some detachment and space in there.

One more thing, that when you said Mama Aya I realized I hadn’t really come full circle to this feminine mother energy. Because you had talked about the masculine energy of peyote, but that was such a gentle masculine anyway. And I thought one other thing that I carried from it was that as the medicine was wearing off and I was coming up out of the levels, I transitioned from the heal thing, where my hands were in blessing to heal. And I want to share this because this is so applicable to any human being. I felt this motherly presence wrap around me. Through my own arms, my arms. And the way a mother would take a baby and just like we were, I was then getting my words back. I was becoming the Amy that I’m more familiar with again, coming back up. And I was kind of talking to her saying, “I’m so scared, I’m so scared. I’m not going to be able to do the podcast the way I want to. And what if I make mistakes? I’m afraid.” And at the time I was still writing my thesis. “I don’t know if I can do it. It was so overwhelming and I’m having to travel and what if I neglect my kids while I’m finishing my thesis? What if I don’t graduate?” And it was just this big mother that was somehow me. The divine mother that I needed to just hold me was me!

The divine mother that I needed to hold me was me

And it was so comforting and it is what I needed. And I kept hearing, “You can do it. You’re strong enough. You’re strong.” And I have used that since. When I feel alone, I feel like I’m quite alone sometimes on my path. And I sometimes find myself wishing I had more of a comforter or a role model or somebody who’s done this before me. And then I come back to what Mama Aya gave to me. Was that everything I needed was inside of me anyway. And so that was a beautiful takeaway that I’ve used since, too. Even just hugging yourself and being like, “I’ve got you. You’re good.” That was really beautiful and a huge, huge gift.

AG: When you were talking about peyote and that it was really difficult, again, like Bre was talking about how that integrates and ties back to your Mama Aya experience with the wolves. And that the wolf is the teacher and that you really were in very real action, teaching Bre and I, who have also lived a lifetime in patriarchy to not listen to our bodies. Like you said, asking the question, “Well, am I going to die? If I’m not going to die, I should probably go do this thing, rather than disappoint somebody else.” And you very much taught us the importance of not betraying yourself. And whether you had found out afterward that you had pneumonia or not, it was still the right choice for you. And it is very validating to find out afterward that you did have pneumonia, but either way, before you knew that, it was you listening to yourself. And then coming to your community and teaching Bre and I and giving us permission to listen to our bodies and trust ourselves. And so, I think that is such an interesting tie in, that the peyote experience for you ended up being a completely different experience. But going back to that you are the medicine. Through peyote, you learn that you are the medicine without ever sitting with peyote.

AA: Yeah, that is powerful. Thanks, Alicia. And thanks, Bre. Thank you so much for being here. Thanks for caring and for making this interview safe, and I was going to say comfortable but it wasn’t. It wasn’t comfortable. But you did everything you could possibly do, and you did such a beautiful job helping me to share those experiences.

BL: We always joke about that, actually. When people work with us, they’ll say, “Is it going to make me uncomfortable?” And we’re like, “Yeah, for sure. In so many ways it’s going to make you uncomfortable.” Even resharing it can sometimes be, you know, I’m going to have to trust myself and be on my own side.

AA: Yeah. I’m already having a massive vulnerability hangover right now. I’m like, what have I just done? But thank you for being here with me and I’ve learned so much from you in your episodes on Grandfather Peyote. And thank you for helping me to share my story about Mama Aya today. It’s been a joy, so thank you for sharing it.

BL: Thank you for being open to sharing it. And when you had that hesitation of maybe not sharing it, to do it anyway. I’m sure you checked in with yourself and felt like it was the right thing to do. But I really think that it’s going to be a great episode, and your listeners trust you. It’s really a neat experience to be able to see this side of you as not always the interviewer, but to have a little bit more of a personal dive with you on a topic that’s really meaningful to you and a very personal experience.

AG: Yeah, this felt like a gift. It was so beautiful and so wise and profound. I loved every moment.

I won’t let her die.

I’ve got you.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!