“patriarchy is a terrible relic of our past”

As we’ve discussed in Season 1 of the podcast, there is a strong and encouraging history of men aligning with feminist causes and contributing to feminist movements. This is a history that dates back at least 175 years to Frederick Douglas speaking in favor of suffrage at Seneca Falls and to John Stuart Mill advocating for women’s rights before British Parliament. From the very beginnings of First Wave Feminism, there have been men of integrity standing alongside our foremothers, and that tradition of male feminism continues to this day. Which is good, because we need them.

We need people of all genders working together if we’re going to create the future feminists envision, but we especially need men to consider how they can play an active part in promoting change and in encouraging others to do the same. Fundamentally, this work we are asking of men involves examining their motivations and assumptions, it means admitting difficult truths, questioning deeply held beliefs, and having the courage to share this work with others – and I couldn’t be prouder to say that today we’ll be joined by two phenomenal men, Jon Ogden and Erik Allebest, who are stepping forward to lead the way.

Our Guests

Jon Ogden

Jon Ogden (he/him) is founder of UpliftKids.org, a lesson library and curriculum that gives families a foundation after a faith shift.

.

Erik Allebest (he/him) is the husband of Amy McPhie Allebest. He is a huge supporter of Breaking Down Patriarchy and of Amy. They have 3 daughters and a son. Erik is the CEO of Chess.com. He also loves playing any kind of game and doing almost any kind of physical activity.

Erik Allebest

Jon Ogden

Him Him Him: How I Know the Patriarchy Still Exists

I didn’t really notice the patriarchy until the day my wife proposed a simple thought experiment: Take our experience in our Mormon faith tradition and invert the genders.

Imagine, for instance, that local congregations were led by women, imagine that all but a handful of the speakers at the Church’s semi-annual worldwide gathering were women, imagine that the first prayer offered by a man at this gathering was in 2013 — nearly 200 years after the Church was organized.

It’s such a simple thought experiment, one that should be applied to all organizations we belong to. And it shifted my worldview so much that when a leader in our congregation spoke up during a meeting a short time later and said that our church was the most sexist organization he belonged to, I couldn’t argue otherwise. The data — and my new realizations about patriarchy — bore it out. I’d just been swimming in the waters for so long I hadn’t noticed.

Around the same time, I read Amy’s viral article “Dear Mormon Man,” and it cemented everything for me.

My initial reaction to all of this was to stretch my religion, make it modern and progressive, to double down on my belief that God loves all people. I viewed my theology as metaphor and pulled wisdom from around the world rather than just my tradition. I was hungry to create a more expansive and inclusive view of spirituality.

This view has widespread adoption from people I admire in broader Christian circles, including Rachel Held Evans, Rob Bell, Richard Rohr, and more. These progressive faith leaders have expanded the scope of Christian spirituality, sometimes at a cost to their own comfort in the face of a hostile crowd of literalist and nationalistic Christian believers. For instance, after the pastor Rob Bell wrote the book Love Wins, which argues that hell is a metaphor and God loves everyone on earth without stipulation, so many of his congregants left his church, he had to shut it down. Such is the risk of carving out a more expansive view of Christianity.

For my part, I adopted this more expansive view of religion, and for the first time in years things started to feel clear and settled.

But lately I’ve felt a new tension rising — a tension that has to do with teaching my own kids about spirituality. I’m putting together a wisdom library of the most transformative ancient religious texts, and I’m feeling the pinch around pronouns.

It’s like this: I’ll encounter an expansive view of the divine in a book like Rachel Held Evan’s What Is God Like? — a book that doesn’t use gender or pronouns for God. And then I’ll read a Bible story to my kids and find myself dancing around the references to deity. It’s all him, him, him.

Do I want my kids to see God exclusively as a male figure who killed millions of people according to the Old Testament? Or would I rather have them see that this character was created by an ancient tribe that experienced life as brutal and so patterned their god in that fashion?

How do I teach my kids that God is loving and expansive beyond the limits of any pronoun and then read to them a text that says God is the opposite?

And it’s not just Old Testament brutality that I’m wrestling with. The New Testament carries this same problem of pronouns. To illustrate, the progressive Latter-day Saint theologian Adam Miller has worked to make our religion more expansive by offering a metaphorical reading of Christ’s resurrection — a reading that is about experiencing inner transformation not just in some eventual afterlife, but right now.

I was hungry to create a more expansive and inclusive view of spirituality

Speaking of this transformation, he says, “I promised to always remember him. I promise to think what he would think and to do what he would do. I promise to pray for his will to be done. Not mine. I promise to be part of the body of Christ. I promise to let the light and life of his resurrection shine in me. In this sense,” Miller says, “the resurrection isn’t only for the next life. It’s meant all the more for my troubled present.”

It’s a beautiful idea.

But there it is: Him, he, his. As though in order to be truly transformed, we’re all supposed to be male.

In so many of my encounters with ancient holy texts, this problem stares at me. “There is no deity but Him,” says the Qur’an, coupled with a range of passages that subordinate women to men. Similarly, Buddhist texts impose heavier burdens on nuns, positioning them as lower in status than monks. And for all his talk of virtue, Aristotle bluntly wrote, “the male is by nature superior and the female inferior” influencing Western culture with such lines to this day. Even Plato, who in moments spoke in favor of equality between men and women wrote, according to one translation, “That which is dear to God is dear to him because it is loved by him.”

In other words, all my desire for expansiveness reaches a limit whenever I try to hold onto these ancient texts. There it is, always: Him, him, him.

So I ask myself, Should I just do away with reading ancient texts to my kids? It’s a possibility I entertain. And yet part of me feels that there’s a real loss in cutting our ties to ancient words.

I don’t have answers. If you do, I’d love to hear them, as I’m eager to raise my kids with an expansive view of spirituality while also helping them understand that ancient wisdom texts are an important part of the human story and experience.

…there it is: Him, he, his. As though in order to be truly transformed, we’re all supposed to be male...

One approach I’ve taken is to find all the ancient texts from women I can, so I can expand the number of perspectives my kids encounter. One such text includes Women in Praise of the Sacred by the poet Jane Hirschfield. She writes, “Spiritual experience is fundamental to human life, and the profound connection that exists between each individual and a reality larger than the narrow or personal self (and yet fully resident within that self) is at the heart of every religious tradition.” She continues, “Still the descriptions we have of this most intimate of encounters—the self meeting the Self—have come to us predominantly through the words of men. This is not because the experience of the sacred is more common for men than for women, but because until quite recently social factors have for the most part encouraged men, and not women, to record their experience.”

Then Hirschfield adds, “The numinous does not discriminate” and “infinitude and oneness do not exclude anyone.”

It’s a powerful concept — one that rings true.

And yet I see three limitations here: 1) There simply aren’t many ancient female texts to choose from 2) Many ancient female writers, from Julian of Norwich to Teresa of Avila, often focus their writing on a male god, so their works end up still being male-centric. 3) Ancient female texts often tend to be poetry rather than story, and young kids tend to be far more interested in story.

So, at some level, I’m still stuck. And maybe there’s no way around it. We can’t go back and change the human narrative, which, at least since recorded history, has been dominated by patriarchy. And because our texts have been dominated by patriarchy, there might be no way to tip the balance completely — at least for hundreds or thousands of years. As long as we read old texts we will always be encountering him him him.

Another option, and perhaps the only true option, is to include a contemporary female-centric voice alongside every ancient male-centric voice. But that’s a challenge in itself, as contemporary voices don’t have the centuries of polish that ancient voices have. We know all the shortcomings of Mother Teresa in a way that we don’t know all the shortcomings of, say, Teresa of Avila because Mother Teresa’s life and views were closely documented for many many decades. As a result, there’s plenty of legitimate criticism of Mother Teresa to go around. And still, she said things that are worth taking to heart.

If we want to keep a connection to ancient wisdom texts alive — and I believe we should — we must do the work of making them more expansive and equal.

This matters because narrow readings of these texts are still affecting how we live today. To give a final example: In her book Cassandra Speaks, Elizabeth Lesser recounts the words of a high school athletics director who, a few years ago, complained about the school’s policy of not wearing athletic shorts. “If you really want someone to blame,” he said in a video recording, “blame the girls. Because they pretty much ruin everything. They ruin the dress code. … They ruin … well, ask Adam. Look at Eve. That’s really all you really gotta do, OK. You can really go back to the beginning of time. So, it’ll be like that the rest of your life. Get used to it, keep your mouth shut, suck it up, follow the rules.”

Such is the view of someone who deeply believes a fundamentalist reading of scripture, a view that could be echoed by fundamentalist believers in a wide range of religions around the world.

It’s a view I don’t want my sons to hold, even as they encounter ancient texts.

I want them to look around and know that the world is so much more than him, him, him.

Erik Allebest

At times in my life, I‘ve felt scared, I’ve felt frustrated, I’ve felt disempowered, and I’ve felt underestimated. But I have never felt scared because I’m a man. I’ve never felt frustrated because I’m a man. I’ve never felt disempowered because I’m a man. And I’ve never felt underestimated because I’m a man (actually, except for one time when my then future-wife Amy could not believe I was going to repair my own pants on a sewing machine. Which I did, thank you very much).

I’ve heard people say that patriarchy is an illusion because men have problems too. But being a man doesn’t mean never having problems. I have lot of problems. Being a man means never, or maybe very rarely, having problems because you are a man. And when men do, it’s often problems made by other men in power. Being a man means almost never being scared you’re going to get physically or sexually assaulted. Being a man means almost never being frustrated because you feel yourself being taken advantage of because of your maleness. Being a man means never being disempowered simply because of your gender. Being a man means never being underestimated as too dumb, too weak, too inexperienced, too unserious, or too ‘just not right’ because you don’t have a Y-chromosome. Life is hard for men, but life is almost never hard because you are a man.

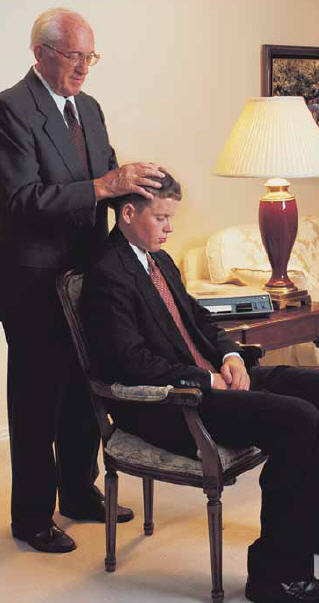

Growing up as a young man, I obviously always knew I was physically different from women and I knew that how I experienced life was different from most women in many ways, but I didn’t recognize the patriarchal structures and how they impacted women both practically and emotionally. The only thing I knew about patriarchy was that it was a blessing. Say the word ‘patriarchal’ to a Mormon and they’ll respond with the word ‘blessing’. In practice, a patriarchal blessing is a special moment when you are about 14 years old where an old man who is designated as the community’s patriarch (often someone you’ve never met) puts his hands on your head and tells you about your past, present, and future. When a teenager is receiving this patriarchal blessing, for boys they tell you that you will grow up and go on a mission and get married and provide for your family. For girls, they often tell you that you will grow up, get married, and take care of kids. Shazam! And that’s your future.

In spirit, the word ‘patriarchy’ being associated with the word ‘blessing’ made us all feel we were so fortunate to be cared for and guided by the men who were in charge – and that’s how god wanted it. Plus, the patriarchy never really seemed like an imbalanced, negative thing where men dominated women because I always knew lots of really strong women growing up. My grandma was as loud, commanding, and scary as any man I knew. And my mom was as smart, funny, and adventurous as any man I knew. So, I didn’t really see any difference in genders other than unimportant things like clothes, movie preferences, and how much time they spent getting ready for the day. And the men and women I knew were just doing their prescribed roles: men make money, women raise kids. In the suburbs of upper-class Orange County, California – and in the micro-community of Mormons I grew up with – that was true for 100% of the adult I knew. Every man was a professional making money, and every woman was staying home taking care of kids. And even when their kids were in school all day or after they’d left for college, they’d been so discouraged from pursuing their own aspirations and so conditioned to depend on men, that they continued to stay at home even though they had few responsibilities. And when I went to church, that’s what I heard everyone was supposed to be doing. That’s what the men in charge told everyone to do, so everything lined up perfectly with what god wanted. All was good.

It never occurred to me that many women were unhappy because of the structural limitations and societal constraints in place. I wouldn’t have even been able to understand it because I, as a young man, never felt it. There was nothing I wanted to do that I could not do because of my gender. In high school, I didn’t make the wrestling team because I wasn’t strong enough…but no women could make the wrestling team or the football team or many other sports teams because there were fewer programs for them. I also didn’t want to be a doctor when I grew up, but the young women around me were being told they shouldn’t be doctors even if they wanted to, since that would jeopardize their ability to take care of their future children. And, if I ever did hear a woman wanting to wrestle or be a doctor or do something that wasn’t ‘feminine’…there was definitely something wrong with that woman, not the system.

…men get the full spectrum of choices and opportunities, and women get to choose from a few prescribed roles…

It wasn’t until many years later that I realized how unhappy many of those women I grew up around really were. They were doing their duty at home and showing up on Sundays in perfect dresses, but many of them were depressed, frustrated, and angry. Some of them were conscious of the reasons why and kept their mouths shut, though I speculate that most of them simply did not understand that the angst they felt was caused by the limitations and the confined roles imposed by patriarchy. They didn’t know that their depression came from constantly being put in second place by men and having their entire lives dictated by men. They could never be the full person they wanted to be.

Occasionally, a woman in our church congregation would break down and we would hear whispers of addiction, rehab, or depression. Men did too, of course, and all of that was explained to me as caused by sin or a lack of faith, and that the answer was more obedience and more giving yourself over to god’s plan. The prescription was always more patriarchy.

Patriarchy means men making rules for everyone and usually choosing the best parts for themselves. Men get the full spectrum of choices and opportunities, and women get to choose from a few prescribed roles. Men get to be in charge of everything and women get some token leadership roles leading other women and children, and occasionally being asked for their opinions by male leaders…which the men have full power to accept or ignore. Men protect each other when they do bad things and women stay quiet. Patriarchy was explained to me as the solution to the evils of the world. What I didn’t understand at the time was that those evils were things like ‘individual will’, ‘freedom of self-expression’, and ‘being true to yourself’.

It’s a strange irony, to me, that America – the land of the free and home of the brave – is still so far behind in giving those freedoms to women and shames instead of celebrates the brave women who dare to question the system. Men, we can do more to break down patriarchy. Here are 7 concrete things that I think we can do to help women:

1. Accept women being whoever they want to be, just like you get to.

De-genderize all the things: dishes are not for women, motorcycles are not for men. Recognize a woman’s right to choose whatever career they want and whatever hobbies they want and live their lives however they want. Don’t comment on their choices in a gender-biased way. I once told a man about a TV show that I thought he would like, but then said to his wife that she wouldn’t like it because it was ‘all about business’. She was finance major in college. I was an idiot.

2. Don’t underestimate women.

If a woman does something typically male really well or knows something that you think most women don’t, don’t act surprised. When you do, it’s like adding ‘for a girl’ on the end of your sentence. I was once vocally surprised that a woman knew about a particular programming language, that made her feel bad and me look stupid.

3. Treat women like you treat other men.

Don’t make very encounter into something potentially sexual. And on the other end of the spectrum, don’t ignore women. Just be normal! Talk. Make eye contact. And don’t constantly flirt. I’ve been told by many women that they appreciate that I talk to them like normal people.

4. Be a good listener.

Women need to talk about their experiences, especially about patriarchy. Don’t invalidate their stories or feelings just because you don’t see it that way or know someone else who doesn’t experience the same thing. Sharing helps heal. I will admit that this isn’t always easy for me, and that I have a naturally lower desire to listen. But I recognize its importance and do my best to listen without being judgmental, defensive, or impatient.

5. Try seeing things from their point of view.

Put yourself in the shoes and experience their lives and stories from their position, not how you would see it as a man. Ask yourself if you would want to be treated the way they are. If you don’t know how to do this, I recommend you read my wife’s essay titled ‘Dear Mormon Man, Tell Me What You Would Do.’

6. Work against your biases.

It’s not enough to try to not be biased because that alone won’t undo the bias that is already there. You have to go further. If you’re hiring, don’t just try not to think of the candidate as a woman, instead, think of her as a woman who could absolutely crush this job.

7. If you see other guys doing any of the stupid stuff above, be a bro and point it out in a positive way.

Honestly, patriarchy is a terrible relic of our past. It is perpetuated by outdated views that powerful old white men know best how everyone else should live their lives and have created narrow definitions of what it means to be a man or a woman. Let’s break it down so everyone, not just men, can be who they want to be.

Life is hard for men

but life is almost never hard because you are a man

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!