“this really rich intellectual tradition that has existed for 200 years”

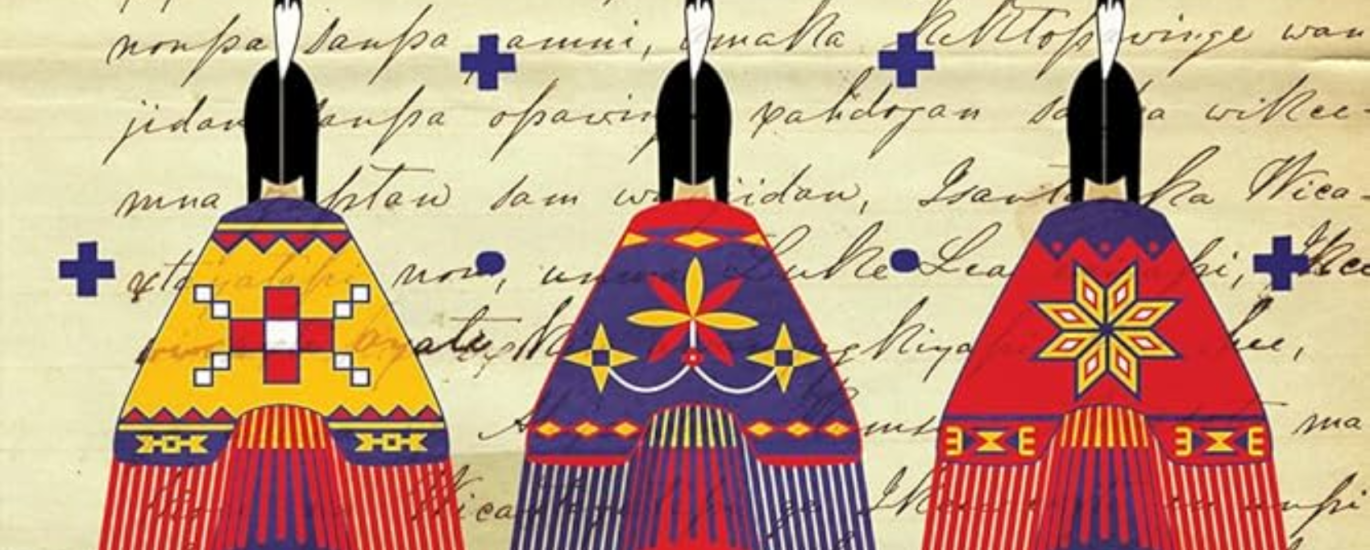

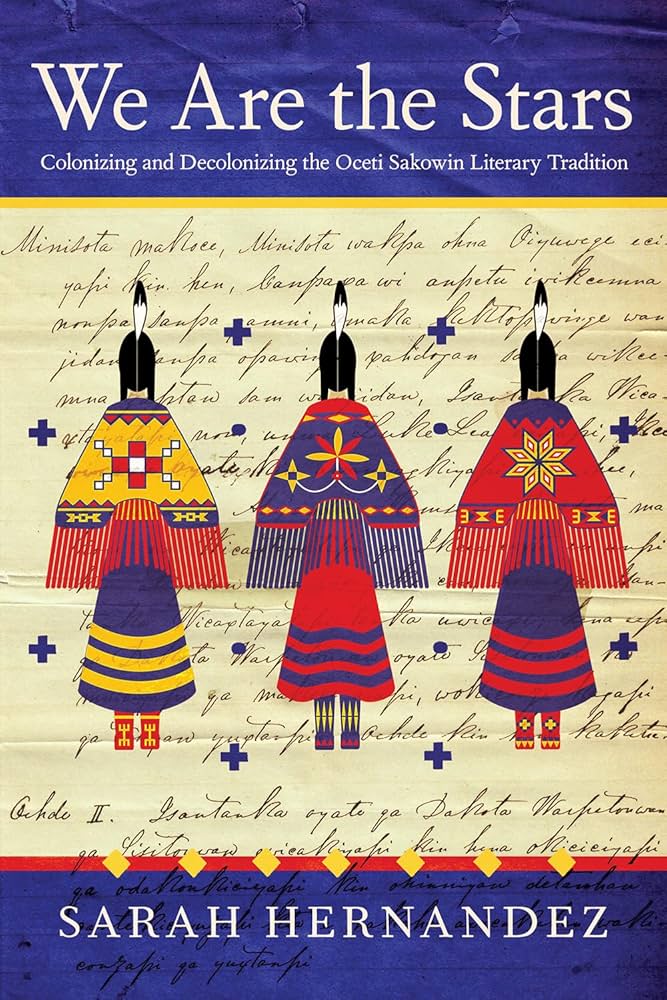

Amy is joined by Dr. Sarah Hernandez to discuss her book, We Are the Stars: Colonizing and Decolonizing the Oceti Sakowin Literary Tradition exploring the devastating affects of missionary mistranslations and the ongoing effort to reclaim sacred stories in the Oceti Sakowin tradition.

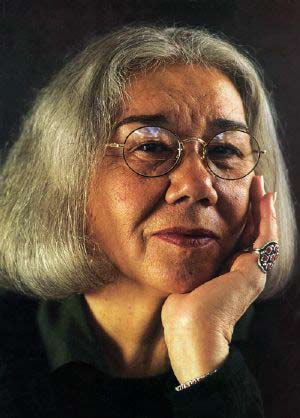

Our Guest

Dr. Sarah Hernandez

Sarah Hernandez (Sicangu Lakota) is an assistant professor of Native American literature and the director of the Institute for American Indian Research at the University of New Mexico. She is the literature and legacy officer for the Oak Lake Writers Society, an Oceti Sakowin-led nonprofit for Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota writers. Under Sarah’s leadership, the Society launched #NativeReads: Great Books from Indigenous Communities, a national reading campaign that increases knowledge and awareness of the Oceti Sakowin literary tradition. She has also published articles in the Wicazo Sa Review, Studies in American Indian Literature, English Language Notes, and Great Plains Quarterly.

Sarah’s book, We Are the Stars: Colonizing and Decolonizing the Oceti Sakowin Literary Tradition, was published February 2023 by the University of Arizona Press in the U.S. and the University of Regina Press in Canada.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Do you know the first book that was published on American soil? It was published in 1653 and it was the Algonquin Bible, as in the King James Bible translated into the Algonquin language, with the purpose of converting the Algonquin people to Christianity. Over the past three centuries, missionaries have translated portions of the Bible into 46 indigenous languages. There are only six complete editions of the Bible published worldwide in an indigenous language, and one of them is the Dakota Bible, which was translated by missionaries in what is now known as Minnesota in the 19th century. This version of the Bible was based on the incomplete and incorrect understanding, and extremely biased assumptions of white Christian missionaries. These mistranslations helped white invaders colonize the Dakota language, literature, life, and ultimately, land. Had you ever thought about the process of translating the Bible from English into indigenous languages? Had you ever thought about how the Bible was used as a tool of colonization? I had never learned about these topics before, and I was so fascinated to learn about them in the book We Are the Stars: Colonizing and Decolonizing the Oceti Sakowin Literary Tradition by Sarah Hernandez. I’m so excited to welcome Dr. Hernandez to discuss this topic today. Welcome, Sarah!

Sarah Hernandez: Hi, Amy. Thank you for inviting me to be on the podcast.

AA: I’m so excited to have you. As usual, I will introduce you first, I’ll read your professional bio and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourself more personally in a minute. Dr. Sarah Hernandez, who is Sicangu Lakota, is an assistant professor of Native American literature and the director of the Institute for American Indian Research at the University of New Mexico. She is the literature and legacy officer for the Oceti Sakowin Writers’ Society, an Oceti Sakowin-led non-profit for Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota writers. Under Sarah’s leadership, the society launched #NativeReads, Great Books from Indigenous Communities, a national reading campaign that increases knowledge and awareness of the Oceti Sakowin literary tradition. She has also published articles in the Wicazo Sa Review, Studies in American Indian Literature, English Language Notes, and Great Plains Quarterly. Sarah’s book that I mentioned earlier, We Are the Stars: Colonizing and Decolonizing the Oceti Sakowin Literary Tradition, was published in February, 2023 by the University of Arizona Press in the U.S. and by the University of Regina Press in Canada.

So, that’s a little bit about Sarah’s professional biography, and now, Sarah, if you can introduce us to who you are a little bit more personally, where you’re from, your education, and some of the factors that made you who you are today.

SH: Yeah, sure. Thank you again for having me on the podcast. Like you said, I am Sicangu Lakota. My family is from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. Even though my family is from Rosebud, I grew up in Denver, Colorado. My parents are Samuel and Cynthia Hernandez, and my dad is actually from Mexico, he’s from Jalisco, Mexico. And my mom is from Rosebud. She was born and raised in Rosebud, as were my grandparents, John Flood and Leona Cologne, who are from Oak Creek and White River. And as Lakota people, we always tell where our family is and where we come from so that the community knows us, and that’s why I give that background. But my family grew up on the Rosebud reservation, but eventually they did leave to Denver, Colorado, which was where I was raised. Growing up, every summer we would go back to Rosebud to visit family, but there’s a big difference between living on the reservation and visiting once in a while during the summer. I grew up in a very large family here in Denver, a very loving family, but we didn’t always have access to our culture or to our oral traditions. And so growing up, I really had never heard any of our oral stories. I had never read books by a writer from my tribal community. So when I went to college, I made the conscious decision to learn about writers from my specific tribal community.

Personally, I just think it’s really important for individuals to see themselves reflected in textbooks and in curriculum, and I never had that growing up. I didn’t read a book by a Native writer until I was 19 years old as an undergraduate student. And I still remember that book that I read, it was James Welch’s book The Death of Jim Loney. I remember reading that book and he was describing some of the characters, and I remember there was a point where he described his sister and suddenly my mom’s face popped into my head. And I was like, “Wow, that’s never happened where I’ve read a book and I’ve seen somebody from my own community in that description.” So, that was really powerful for me. But again, that didn’t happen until I was 19 years old. And then I didn’t read a book specifically by somebody from Rosebud until I was 25. I remember then it was Joseph Marshall’s book The Dance House. Again, it took a long time for me to see writers from my own community reflected in the literature.

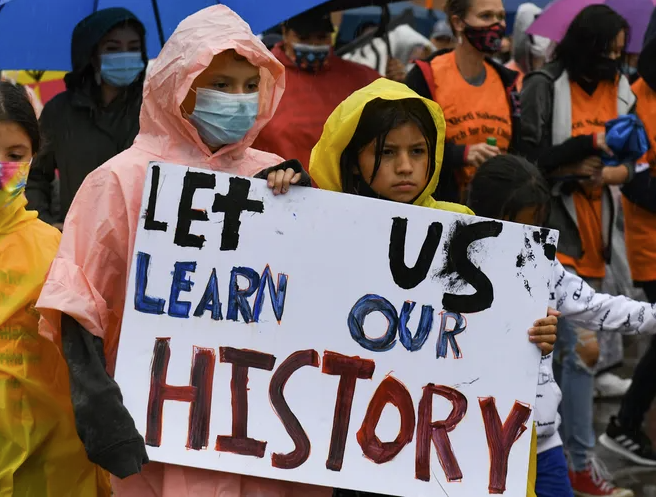

So when I did begin graduate school, like I said, I made a conscious decision to seek out writers from my own community, and I really made a decision that I wanted to make these writers and their work accessible to Native students like myself who didn’t have that opportunity. That’s really my motivation and driving force. I think that as a literary scholar, people assume I just read books and analyze texts and publish them in these academic journals, but that’s not really what drives me. I’m trying to reclaim and recover our literary tradition for future generations. Because what I’ve realized is that we have so many amazing literary ancestors who’ve left behind this great body of work for us. They’ve left behind more than 200 books, but these books aren’t being taught in American schools, right? I’m not the only person who hasn’t read a book by a Native author growing up. This happens quite commonly, quite frequently in our communities.

My goal as a scholar isn’t just to publish these literary essays for academics, it’s really to create resources for community members. And so We Are The Stars, I’m really glad that it’s been well received by the academic community, but that’s not who I wrote it for. I wrote this book for people within my own community so that we can start to learn more and really appreciate our rich literary tradition. Because for so long, we’ve been told that we don’t have a literary tradition. We’re told in schools by anthropologists and historians that we have this extinct oral storytelling tradition, but we don’t have these rich intellectual traditions. So as a literary scholar and as an educator, I’m really trying to challenge these misconceptions and show that we have this longstanding rich intellectual tradition, and we’ve had one since time immemorial, first as an oral tradition and now as a literary tradition, and as we move into the future, as this digital literary tradition. But we do have this really rich literary tradition.

AA: Wow, that’s really, really amazing. I love knowing that reading the book, now in retrospect, the dual purpose. It functions amazingly as this educational book, like you said, for the academy, but then that’s really special that that is for your community. It reminds me of bell hooks. She always said that when people would ask her who she’s writing for she would say, “My mom. People in my neighborhood.” Yeah, really neat. Well, let’s dig into the book. I enjoyed this book so much. I learned so much from it and highly recommend it to listeners and viewers who are interested in learning more. And like I said, I had never considered the way that literature can be used in colonization. That’s something that I had never learned or thought about before. Maybe we could start with you setting the stage for us and tell us who the Oceti Sakowin are, right in the title of the book. Who are they? Where are they from? Kind of orient us a little bit.

SH: Yeah, yeah. I also want to mention, I really like that you said that you never thought of literature as something that could be used in colonization. And I don’t think I ever thought of literature as something that could be used to colonize and now decolonize, but it was really Elizabeth Cook-Lynn who pointed that out to me. She said that literature has always been used to possess and dispossess people. So I really had that quote in mind when I started writing and researching this book. But before I get too much more into that, I do want to answer your question about who the Oceti Sakowin are. Historically, most people know of us as the Great Sioux Nation. We see that everywhere, right? The Great Sioux Nation, but that’s not how we describe ourselves. We describe ourselves as the Oceti Sakowin or the Seven Council Fires. Traditionally, there were seven main tribes that made up the Oceti Sakowin. Because of colonization, our tribes have been divided and split, but the Oceti Sakowin are seven tribes and were divided by dialect, by geography, by history, by language. So you’ll hear me saying the Oceti Sakowin, but you’ll also hear me saying Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota, because we also describe our communities by our dialect, right? And I’m Sicangu Lakota.

People often ask me, “If you’re Sicangu Lakota, why are you writing about Dakota people? Don’t you know there’s a difference between Dakota and Lakota?” And I do very much know there’s a difference between our different tribes, between Dakota and Lakota. But in this book, I purposely started with the Dakota because they’re our relatives who are the furthest east, meaning that they were the first of our relatives to be encountered by missionaries and by other settlers. And what I argue in the book is that these missionaries and settlers worked with the Dakota, developed this colonial blueprint to colonize our language and our literature and land. And then they applied the same blueprint to the Lakota and the Nakota people. There are a lot of similarities between Dakota, Nakota, Lakota people, but we also do have very unique languages, cultures, and histories that impact our families and our communities and individual people.

I always really try to emphasize these tribal differences, which I don’t think historians and anthropologists have always done in the past. They’ve always just referred to us as “the Great Sioux Nation” like we’re all the same, but we’re not all the same. We have different creation stories, we have different languages, we have different interactions with the United States, and we are all very unique in that way. But collectively, we describe ourselves as the Oceti Sakowin, the Seven Council Fires. Traditionally, our homelands were from the Black Hills to the Minnesota Valley, so it would be present day Minnesota, South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska, up into Canada. Those were our traditional homelands, and we were hunters, nomadic people, but we also have these creation stories that tie us to specific sites in these homelands. As I mention in the book, the Dakota people, their creation stories link them to Mni Sose, the Missouri River, to a very specific spot in present day Minnesota, which is what we call Bdote, where they believe their ancestors emerged from the water to come on earth. Lakota people have a slightly different creation story. Our creation stories tell us that we emerged from rock from hills, and that’s primarily where we live. That’s where our culture and language is all tied to, similarly with the Dakota and then the Nakota as well. Their creation stories also tell them they come from rock, but at a different site in Minnesota. So there are definitely similarities between our languages and cultures but there are also important differences that I think are important to acknowledge.

AA: Mm-hmm. Yes. Thank you so much. Talking about the Oceti Sakowin, where would they fall on the spectrum of patriarchal to egalitarian to matriarchal? Where do they fall in their gender norms and traditions?

SH: Very much a matriarchal society, and our creation stories tell us this as well. I know that in Christian creation stories it’s woman who came from man, right? But that’s not the story that the Lakota people or Dakota people tell themselves. They were created to complement each other. It wasn’t this hierarchy that exists in Western society. The male and the female genders were created almost simultaneously, but they were created to complement each other. And I think that’s the biggest difference between Western perceptions of gender and tribal perceptions of gender, is that we don’t have that hierarchy where we don’t feel like males and the work that males do is somehow superior to what women do. Albert White Hat described it really well in his book Life’s Journey – Zuya: Oral Teachings from Rosebud. He explains how these roles have always been complementary to each other. It’s necessary to survive, but we need to work together to actually have a functioning society.

that’s the biggest difference between Western perceptions of gender and tribal perceptions of gender…we don’t feel like males and the work that males do is somehow superior to what women do

AA: Totally. That’s one thing that I’ve really noticed in studying history with all different cultures all over the world, through all time, as far as I can tell, there has been gendered division of labor. Every culture has their, like, “These are the tasks that we’ve decided that men will do, these are the tasks we’ve decided women will do.” They’re different for cultures and times. Some feminists will say, “You can’t have gender roles, we’re against gender roles.” And I think for me, the more key issue is like you said, a hierarchy where it’s men assigning the gender roles and saying, “We’ve decided what you’re going to do and we’ve decided what status it has,” versus everybody coming together or at least just being like, “Yeah, nobody’s above each other.” We’re just all pitching in and there’s no gender that says, “We preside over you and tell you what you can do.” That’s how I see it. There’s no problem with humans dividing up the work, but it’s just people telling each other what they can do and can’t do.

SH: And I think one of the things I’ve learned while researching this book too, is that there’s a lot of, I guess you would call it slippage between those traditional gender roles, right? There are times when women maybe took on some of what would be considered the more masculine roles and men took on some of what would be considered the more feminine roles. We talk about a third gender, about two-spirit, so we do allow for those differences. They’re not these really strict gender roles that we have in Western society. We had those before the missionaries came and colonized and said, “Women do this, men do this, and men are the head of the household.” That existed before colonization.

AA: Yeah. So important. Yes, thank you for bringing that up. I was actually just talking about it with my kids, and we said the same thing, that another really important feature if it’s going to be fair, nobody is in charge of the other one. And for people who are like, “I don’t feel like I fit in what you’re telling me I’m supposed to do,” to allow for that. That’s so great. And you just mentioned the next question I was going to ask, which is: what changed? And I know that we could spend two hours talking about the effects of colonization, but maybe just some of the main features that you want to mention. What changed in the culture once European contact happened?

SH: Yeah. So, one of the things I talk about in the book is that obviously we always talk about settlers, but I really try to emphasize that it was Christian missionaries who were among the first settlers in Dakota territory, and they really had a huge impact on colonization. As white Christian men, they had their own ideas about gender, they had their own ideas about who was in charge, as you were saying. All of this was established when the missionaries arrived, and they really forced this upon Dakota people. For instance, one of the things I mention in the book is that traditionally with treaties, women were our cultural and national leaders. Men always turned to the women for political advice, even signing these treaties. Missionaries didn’t think that women needed to play any role in signing these treaties, so they only dealt with the men and women were suddenly excluded from this important leadership role in our society. That would be one example.

The missionaries thought that women needed to be domesticated, and they would hire Dakota women to be house servants. And one of the things they really broke up was marriage. The Oceti Sakowin traditionally had polygamous marriages, at that point it wasn’t uncommon for one man to have multiple wives. And in Western society, we think of this in terms of something sexual, as if the man just wanted to sleep with a number of different women. But that wasn’t the way that they traditionally viewed it among the Oceti Sakowin. A man who took on multiple wives took them on so that he could care for them and provide a family for them. And when the Christian missionaries arrived, they said, “No, this is immoral. You have to break up these families.” And our men were really hesitant to do that.

The other way that Christian missionaries impacted the Oceti Sakowin was that missionaries took over a lot of the roles that were traditionally held by women. One, women were traditionally our oral storytellers. They were our aiders. When missionaries began translating and transcribing our stories, suddenly they became the experts on our oral stories, displacing women from that traditional role they’ve always played as our oral storytellers. And one of the reasons that’s so important is because those oral stories aren’t just stories we tell each other for entertainment, right? Those stories are educational. They tell us our tradition and our values. And suddenly, women aren’t telling those stories as much as these Christian men who are suddenly telling them, appropriating our stories and now telling us how to behave, what’s moral, what’s immoral. So they displaced women from the traditional role of storytellers.

What I also talk about in the book is that once they displaced women as our traditional storytellers and our educators, missionaries started establishing a system of boarding schools, and suddenly they started to replace our women as mothers. There’s this really great quote by Luther Standing Bear, and he talks about how after colonization, he says, “Mother power becomes weak, scattered over to many places, taken over by the teacher, the preacher, the nurse, the lawyer, and others who will superimpose their will.” And I think that’s really the main thing that Christian missionaries did, is they took over a lot of the traditional roles that women played in tribal society: educating our children and keeping our families together. Suddenly it was missionaries who took over these roles. And once they translated our stories, they were imposing Western values. These missionaries were white Christian men, and they had their own biases about women. They had their own ideas about what was immoral and what was moral, and they used literature to superimpose these ideas onto our stories so that we then begin to internalize some of these behaviors.

One of the things I talk about in this book is that we see a matriarchal-patriarchal shift. We go from this primarily matriarchal society to this patriarchal society that is very much influenced by Western culture, and it all starts when these missionaries begin appropriating our stories and changing the meaning of those stories, and changing the values and the lessons embedded in each story. They first colonize the stories, but then they start to work with the federal government to really formalize this, creating a system of boarding schools that will further strip us of our language and our culture and our traditions. They passed the Dawes Allotment Act, which suddenly takes our land, and primarily women were considered the head of the household, but when you have the Dawes Allotment Act, that power suddenly shifts to the men and suddenly the men are the head of the household. Because of these changes, you start to see a change in Oceti Sakowin Society. Again, I think Albert White Hat talks about this really well in his book, Zuya, he says that traditionally we were a matriarchal society, but because of colonization, because we’ve started to internalize some of these Western values, we start to see a shift, especially among our young people, where they adhere to these patriarchal values that tend to oppress women and see them as inferior.

AA: Yes, and you do write in your book about a lot of different ways, different wars that happened and that things shifted afterwards forever. Again, I recommend that people read the whole book and get all of the context, but maybe what I’d like to dig in on most is the literary tradition. Talk a little bit specifically about the Bible, the process of translating, and who these missionaries actually were. Because you write not just about the general missionary effort, but specific individuals. Can you tell us who those people were?

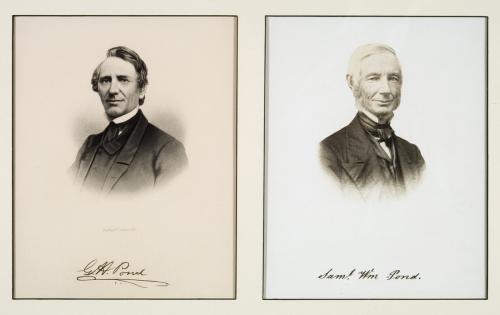

SH: Yeah. When I first started writing and researching this book, I would just say “Christian missionaries,” right? To me, they were all sort of doing the same thing. But then I really started to realize that it was three families that were really integral to the Bible colonizing Dakota language and literature. This would be Samuel and Gideon Pond, who were the first two missionaries to arrive in Dakota territory. These two men were volunteer missionaries. They grew up in Connecticut and suddenly decided that they wanted to Christianize and save the soul of what they call the “wild, savage Indians.” So they took it upon themselves to leave Connecticut, go to Dakota territory, and start to colonize Dakota people. At the same time that they arrived, another Reverend Thomas Williamson, he also arrived in Dakota territory about a year after these two men. He was part of the American Board of Foreign Commissioners, so it was more of an official missionary organization. He had received permits from the government, he went into Dakota territory, and was going to establish these mission stations among the Dakota. The Pond brothers, on the other hand, were just two volunteer missionaries who were suddenly really enamored with the idea of saving Native people, so they just kind of showed up.

This all happened in 1834-1835. These men decided to work together to Christianize Dakota people. Initially when they arrived in Dakota territory, that’s what they said they were going to do. They said, “We’re going to Christianize Dakota people, we’re going to save Dakota souls.” And the quickest way to do that is to teach them how to read the Bible. Missionaries assumed that the Dakota language would be really easy for them to learn. They said, you know, “We’re much smarter than Dakota people, so it won’t take us very long at all to learn the Dakota language and to translate the Bible and a dictionary so that we can communicate. It will be a lot faster for us to learn the language than for them to learn English,” which tells you what they thought of Dakota people. They just assumed that we were stupid and inferior, and that by being smarter, they would learn the language much more quickly. Well, that didn’t actually happen. What the missionaries found out very quickly is that Dakota is a very complicated language and they weren’t able to learn it very easily. I think they assumed they’d learn it in a few years, but it actually took them 40 years to learn the language, and even then, their understanding of the language was quite flawed.

But these missionaries arrived in Dakota Territory and they said that the best way to convert Dakota people is to start publishing a Bible in the Dakota language, and then we can use this Bible to teach Dakota people. A lot of anthropologists and historians regard these missionaries’ work as “the most authentic and authoritative text on Dakota language and literature.” And what I really try to prove in my book is that it’s not the most authoritative text. There were a lot of flaws in the books that these missionaries created. These missionaries created what is known as the first Dakota library. It’s 50 books, religious and secular texts that they were going to use to educate Dakota people. But what I show in the book is that they’re really flawed. They were really imbuing the language with this Christian bias. The very first thing when the Pond Brothers arrived in Dakota territory was that they decided they needed an alphabet to start writing down the words. They just adopted the Roman alphabetic script, assigned Dakota sounds to each one of those letters and said, “Okay, here’s a Dakota alphabet.” They called this first alphabet the Pond Alphabet. And I think that’s really telling, right? It tells you that they didn’t create a Dakota alphabet, they created what was really a Pond Alphabet. They named the Dakota alphabet after themselves rather than the people it was ordered to represent.

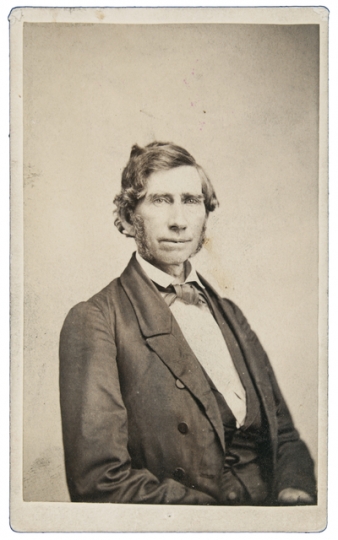

So they created this Dakota alphabet, and then Thomas Williamson decided to use this Dakota alphabet to start translating the Bible into the Dakota language. One of the things I think we have to recognize is that Williamson is already working with the flawed alphabet. The Pond brothers just assigned random letters to each one of these sounds. They acknowledged that they didn’t have all of the sounds or words in the Dakota language, but they were just going to use this flawed alphabet anyway. So Williamson decides to use this flawed alphabet to translate the Dakota Bible, and when you look at his version of the Dakota Bible, he’s also making up words and concepts that didn’t exist. We didn’t have a word for a single God. We didn’t have a word for the Holy Spirit or the Son or the Holy Trinity at all, so Williamson just started to invent words and ideas and concepts that he used to translate his own version of the Dakota Bible. And this was a huge, monumental effort. Again, the missionaries thought that they could do this in a couple years. It wasn’t something they were able to do in a couple years. Williamson called in reinforcements and he called his advisors at the ABCFM for help and they sent Reverend Stephen R. Riggs.

Now, when most people who do know about the Dakota language, they primarily know Riggs’s name. Riggs’s name ends up on a lot of these materials. Riggs was a missionary, but he was also a really shrewd businessman. He decided that he was going to take the Dakota Bible and the Dakota Dictionary and all of these other resources and he was going to publish them with the Smithsonian so that historians and, at the time, ethnologists could utilize these materials. So, whereas the Pond Brothers and Williamson were really trying to learn the language to work with Dakota people, I feel like Riggs learned the Dakota language so that he could make a name for himself publicly as an academic and as a scholar. So Riggs’s name actually appears on most of these materials. Sometimes, once in a while, you’ll find a reference to Pond or Williamson, but primarily Riggs is given all of the credit for publishing the sources. He publishes 50 books in the Dakota language, and those books are books that end up being used in boarding schools.

I talked about how these resources were flawed from the very beginning. All of these things were mistranslated, but once missionaries established boarding schools, they used this Dakota library to educate Dakota people. A lot of times what these sources are now telling Dakota is that you’re stupid, that you’re immoral, that you’re lazy, it’s all of these negative messages tied up in this translated library. So that’s suddenly what Dakota people are reading about and learning about in boarding schools. That’s what I mean when I say that missionaries displace Dakota women in their role as traditional storytellers, because traditionally Dakota women educated our children using an oral tradition and they taught them about the importance and the value of our stories and our culture and our values. But suddenly, these students are physically taken from their mothers, their families, and placed in these boarding schools with these missionaries who use these flawed resources to tell them “you’re bad and everything about your culture and community is wrong.” That has a really detrimental effect that lasts for generations.

AA: Can you talk a little bit specifically, I know in your book you wrote about the words that are gendered in the original language and that in English it strips the feminine association and especially the word for land, right? The way they translated land. Can you talk about that?

SH: Yeah, yeah. The word for land, there are a number of different words for land. Gwen Westerman talks about this in her book Mni Sota Makoce, and she talks about the fact that there are 16 different words for land. She mentions that the word for land is very similar to the word for “mother” in our languages. So she and a number of Dakota scholars talk about the fact that women have played such an integral part in our culture, that it’s embedded in the language. Women have played the same role as land. It’s both the land and women who are the givers of life and nourishment. Interestingly, when I looked at the missionaries’ dictionaries, I realized that they didn’t have any references to “mother” in their new interpretations of land. And I’m not a fluent speaker, so I’m not going to be able to say the specific words for land, but they stripped those definitions so there’s absolutely no acknowledgement that land and women are connected in any way at all. When missionaries start translating words for land, they talk about land in terms of acres and in terms of these commodities, these resources that can be exploited. Very different from the way that Dakota and Lakota people traditionally talked about land as a mother, as this source of nourishment, as a relative. Suddenly those meanings are stripped. And again, these are the messages that young Dakota people are now getting in school. That land and women are no longer linked, that there are two very separate things. We go from thinking of land as a relative to land as a commodity, and that becomes a very Western way of thinking. I think that’s something that a lot of Dakota and Nakota people are trying to undo now, to remind us that there’s this intimate connection between women and the land.

all of these negative messages tied up in this translated library

AA: Yeah, that’s really fascinating. One other topic that you bring up in the book is the translation specifically of the Bible, not the translation of words, but more in this case the translation of ideas and adopting new ideas. You talk about the concept of Adam and Eve and the original sin in the Garden and that that’s just a completely different way of viewing mistakes than would have been like the traditional way. Could you talk about that difference a little bit?

SH: Yeah. After Riggs translates this Bible, he also starts translating some of our oral stories, and two of the first oral stories that Dakota people usually share with children and with people outside the community, are the stories about Mni Sose, which is their creation story about emerging from the river, but also the story about Fallen Star, which is about this hero who comes down from the star world and he helps tribes in peril for all of these different reasons. What Riggs does is he takes this story about Fallen Star and he retranslates it to look like the story of Adam and Eve, which it never was. This story about Fallen Star is about, first, the story begins with this young woman who marries a star, they move to the star world, the woman gets pregnant and is going to have a baby, but she starts to miss her community below. So, she starts digging into the star world, she falls, dies, and the baby is born. And this young baby who is born on what would be Earth becomes this hero who works to save the community from all of these different things that happen.

When Riggs reimagined this story, he reimagined it as Adam and Eve, like you said. He reimagined these women as somewhat, I guess, like seductress type roles, where they are these experienced women who precipitate the fall of man. And that’s never how we told the story, right? In our version of this story, Fallen Star’s mother is a young woman who marries a star and misses her community, creates this hole in the sky, and accidentally falls to the Earth and dies. But in Riggs’s version, Fallen Star’s mother is this woman who deliberately disobeys her husband, digs this hole in the sky, falls down, and dies and has this baby. But in his version, it’s very much more like Adam and Eve, right? It’s this woman who, instead of searching for a forbidden apple, looks for a forbidden turnip and is punished with the pangs of childbirth. That’s really how it’s represented in his story. He takes this tribal story and he reimagines it as this Christian parable.

And again, this is the story that is relayed to young Dakota people. This version that, you know, we have this Adam and Eve type thing where we have this hierarchy where women are supposed to obey their husbands. And if they don’t obey their husbands, they’re punished. Women are evil, they caused the fall of men, all of this is wrapped up in Riggs’s version of the story. But Lakota and Dakota people never told the story that way. It was just a young woman who made a mistake and who had this really tragic death. And despite this tragic death, her young son goes on to do all of these wonderful things to help strengthen and empower his community. But that part isn’t in Riggs’s version. I argue in the book that he does this purposefully. He takes our oral stories and he imbues them with this Christian bias, again, so he can convert our people. The idea is that once you convert our people, you force them to become Christians, they can assimilate into American society and become these upstanding citizens, and that was his only goal. He is very explicit in that. He says, “My goal is to put the word of God into their speech.” That’s all that he’s trying to do when he manipulates our language and our literature.

Yeah, it is very different from the way that we traditionally tell this story. What I think is really positive and empowering now is that you see a lot of Dakota, Lakota, Nakota people reclaiming this story and reimagining Fallen Star’s mother as this more empowering figure. I start to see a lot of Dakota and Lakota writers doing that. One of my new favorite poems is by Taté Walker, and they re-imagined Fallen Star’s mother in this more contemporary context, but again, at this time, she’s more of an empowering figure than she was in Riggs’s version. I’m happy to see that we have contemporary Dakota, Lakota, Nakota people reclaiming that story and not just following along with Riggs’s version that they’re Adam and Eve.

AA: Yeah, it was such an important and really striking passage of your book to realize what you just described, that it’s so infuriating and insulting to have someone change the story, change the plot, change the characters, but that embedded into that, it’s not just a plot change. It’s an ideology change. It’s a whole different way of looking, like I said at the beginning because it really impacted me, looking at mistakes. Well, yeah, people make mistakes, and that’s one of the ways we learn, and then you just go, “Okay, well, now what?” Now we move on having learned that, versus this Christian notion of like, “And that separated them from God forever, and now your punishment is pain in childbirth, because the first woman did this terrible thing.” It’s just not even in a person’s like mentality. And the anger I felt at that being changed and being taught to the next generation of Lakota kids and how infuriated I would feel as a parent and then grandparent and be like, “Wait, that’s not the story, and now along with that has come all of these different beliefs and that is not our way.” I’m just so grateful that that has been changed and that it’s coming back around so that’s not going to be perpetuated anymore. How was it preserved? I don’t remember, Sarah, the original story, there were women writing it down in the original, right?

SH: In the original it was men who had told the story to Stephen Riggs. They told it to Stephen Riggs, and then Riggs had Dakota men write it down and then Riggs translated that Dakota version into English. And Riggs’s English version that keeps getting republished over and over, I think I mentioned that it was almost 10 times that his book has been republished over and over. Meanwhile, the tribal version of these stories have been silenced. Yeah, he initially recruited Dakota men to tell them these stories. And I think one thing to point out is that these stories are so important and so sacred to our people, I don’t think they thought twice about sharing them with younger generations or with sharing them with settlers who are presenting themselves as friends. I don’t think they had any issues with just being open about these stories, but then it was Riggs who took it upon himself to mistranslate these stories and to publish them, like you said, in a way that changes our ideology, the way we know ourselves and our community. In a lot of ways it’s very insidious what he did.

AA: Yeah, that’s terrible. I was just wondering, too, how the original tribal stories were preserved. Because if the misinformed, the wrong ones proliferated and perpetuated 10 different editions, how did the original one survive that so that they can be resurrected now?

SH: Well, one thing that I should probably point out is that I think that a lot of anthropologists and historians are always looking for the original or the most authentic version of the story. And one of the things that we talk about within tribal communities is that there’s not one solid, authentic story. As I mentioned, the Oceti Sakowin all have their own unique stories, culture, language, dialect. That means that some of our oral stories change a bit too, like the version that Lakota people tell themselves about Fallen Star is slightly different from the version that Dakota people and Nakota people tell themselves about this story. This story also changes from not just community to community, but family to family. Different families are going to have slightly different versions of these stories, individuals are going to have slightly different versions of these stories, and that’s okay, right?

For us, these stories are something that is living and that is changing. These stories are told to people for a specific reason at a specific time to learn a specific lesson, and that lesson is going to be different for each individual. You’re going to have this story told to you maybe to, I don’t know, teach you one specific lesson. Meanwhile, somebody else learns a different version of the story to have them learn a different lesson. I think that’s the big difference about the oral tradition is that it’s okay for these differences to exist among our stories, because they are going to differ, like I said, from community to community, family to family and individual to individual. It doesn’t mean that one version is more right or more wrong than the other version. And I think this really frustrated the missionaries and still frustrates, I think, a lot of Western academics today. They want that authentic, original version of the story. Such a thing doesn’t exist. These stories are passed down orally from family to family, community to community, individual to individual. But like I said, they can change slightly with each version.

AA: As long as it’s not some outsider exploiting the story and changing it, right? As long as it’s organic and stays within the family?

SH: Yeah, stays within the family. That was the thing I wanted to mention, is that because of the missionaries’ influence, a lot of our communities took these stories underground and they only shared them with families or with individuals after that. I think we quickly learned our lesson that when you do start sharing these stories with settlers, they can be exploited and they can be used against you. In the book I do talk about how a lot of our stories were taken underground, which may be the reason that some of us who didn’t grow up on the reservation were not going to easily have access to these stories. Like I said, I didn’t have easy access to these stories, and I’m sure my grandparents knew these stories as well, but because of the devastating effects of colonization, and because of all of the trauma associated with that, they didn’t share those stories with my mom, and they couldn’t share them with me.

There’s also that danger that when you take the story underground, there are going to be some people who don’t have as easy access to them anymore. Like I’ve said, I had to make a conscious decision to go back and learn more, and initially my journey was that I used these printed texts that people like Ella Deloria and Elizabeth Cook-Lynn and Lydia Whirlwind Soldier and all of these people published. That’s how I first started learning about the oral tradition. But then I think the way I really started learning more about that is I joined the Oceti Sakowin Writer’s Society, which is a first of its kind tribal group for Dakota, Nakota, Lakota writers. We have about 30 members, but once I joined that group those individuals were so helpful in teaching me about our oral tradition and our oral stories and how to talk about culture and language in ways that are ethical and responsible. Because I never want to be in a position where I’m like Riggs or any of the missionaries where I exploit my community or exploit any of their resources. I’m also really careful about what I talk about and what I share in this book, too. I will talk about stories that have been published and are already available for public consumption, but I never want to take any of the information that the Oceti Sakowin Writers’ Society has shared with me and use it in a book that I can publish to get tenure for myself as an academic. I want to be careful about doing that, too.

AA: Yeah, that makes sense. Well, with our last few minutes, I would love to have you highlight a couple of the women that you just mentioned. Ella Deloria and Elizabeth Cook-Lynn come up a lot in your book and are really important. Could you tell us who they are and what they did?

SH: Yeah, sure. Ella Deloria was born almost a hundred years after the missionaries first published what was called the First Dakota Library. She was born about a hundred years after them. She was in college and she was actually working with a famed anthropologist, Franz Boas, and he knew that she knew the Dakota language, so he asked her to re-translate and correct some of the Pond Brothers’, Riggs’s, Williamson’s translations. So she went through and she started correcting all of these texts and she would share with Franz Boas that there were a lot of inaccuracies in these books, primarily that people like Fallen Star weren’t properly represented. She would share this with Boas that she had concerns about the content of the story. Boas wasn’t necessarily concerned with that, he wanted to fix the grammar. He wanted to standardize the Dakota language, and so he was just really focused on looking at the actual grammar, not necessarily the content of the story. So he kind of ignored all of Ella Deloria’s concerns, and he went ahead and continued to publish Riggs’s, Thomas Williamson’s, and the Pond Brothers’ work without any real alterations. He would maybe add an accent or change the spelling of the word, but otherwise, he kept their translations the same.

I think that, like a lot of scholars, he assumed these were the earliest, most authentic translations. But Ella DeLoria said, you know, “I read these and I know they’re not right. I can’t just let these translations be circulated this way. I can’t not say something.” So Ella Deloria took it upon herself to begin translating, re-translating, and correcting Riggs’s, Pond Brothers’, Williamson’s papers. I talk a lot about that in chapter three of my book, about how she went through this process of correcting and retranslating the work. I call her translation method a literary translation method, so she’s really intent on correcting the content of the story. She went about retranslating all of this, but like I said, Boas didn’t think it was important, so he never bothered publishing any of these corrections. And Deloria spent her lifetime trying to publish these corrections on her own. But as she says, you know, “I’m a Native woman, I don’t have a Ph.D., I don’t have the money, I don’t have the means.” So nobody’s publishing what Ella Deloria has corrected or rewrote.

While I was researching this book, I went to the Ella Deloria archive, which is housed at the Dakota Indian Foundation in Chamberlain, South Dakota. I went there and I looked through all of her different archives, her different manuscripts, and what I realized is that she did begin to re-translate a lot of these stories that Riggs and his colleagues had mistranslated, but none of these stories have seen the light of day, right? They’re still housed in an archive in the Dakota Indian Foundation, and waiting for more and more people to recover them. What I will say is that progress has been made. People who do know Ella Deloria know her book Waterlily, which was published in 1988. That book is well known and widely circulated, primarily, I think, because some of Franz Boas’s colleagues helped her get it published. But there’s a lot more of her work that hasn’t been published.

I can’t just let these translations be circulated this way. I can’t not say something.

Slowly, we see Dakota Lakota people who are trying to recover and reclaim that work. Recently, The Dakota Way of Life was published. I’d like to see this manuscript with Fallen Star finally be published. I was able to publish an excerpt in an academic journal, but I would love for the whole manuscript to be published. One of the reasons I think it might not be published is that I think some people say that it’s incomplete, there are pages missing from this manuscript. But then I think about something like Beowulf, which is also an incomplete manuscript and there are portions missing and yet that’s published and studied over and over, right? That’s something I had to study as a graduate student too, so I think it just becomes an excuse. Why wouldn’t we publish Ella Deloria’s work even if it is incomplete? She’s one of the first Dakota anthropologists and writers who really tried to reclaim that work and challenge those missionaries. I think because of the time period she was born in, she wasn’t able to fully challenge those missionaries. Like I said, publishers and editors weren’t looking to publish a woman. They weren’t looking to publish a Native woman. They weren’t looking to publish somebody without a PhD. So I think because of the time and place she was born in, she wasn’t able to fully share that work in the way that she wanted.

But what I mention in the book was that she was still very innovative, still very much involved with her tribal community. Though she wasn’t able to republish these translations, she’s well known throughout South Dakota. It was so interesting that when I did research for this book, I actually ran into people who had met Ella Deloria. They would say, “Oh, I remember encountering her when I was a young kid and hearing some of these stories,” and that really blew my mind because of the big difference in time. But there are people there who still remember her. She would throw on these pageants and she would share information about our culture and language, but she would do this as an individual person going around to different communities, different schools to interact with students and with teachers and to do this. And so I feel like even though a lot of her work wasn’t published during her lifetime, she found innovative ways to still stay engaged with the community, and the community really rallied around her and supported her in those efforts. I talk about that in the book as well, how our women came together to make sure that Ella Deloria was able to share this knowledge.

One of the people who was really inspired by Ella Deloria’s work is Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, who I also talk about extensively in the book. Elizabeth Cook-Lynn was a mentor of mine, and she just recently passed away last year, actually. It’s been about a year now since she passed away, but Elizabeth Cook-Lynn was actually the person who invited me to join the Oceti Sakowin Writers’ Society and she came up with the title of this book. I had a very boring academic title for this book, and Elizabeth Cook-Lynn said, “No, you need to call it ‘We Are the Stars’ as a reference to our creation stories.” So she came up with the title of the book. She read multiple drafts of the book, and I think it was because of Liz and because a lot of the women who are part of the Oceti Sakowin Writers’ Society that I was really able to flesh out that argument about women.

Women were definitely a part of the book, but I don’t think it was until some of my elders took me aside and said, “Hey, you really need to emphasize this point about women and the land. This is the key part of your book.” So they were there, but it wasn’t something that I had focused on as explicitly until Liz and some of the other elders in our group said you really need to emphasize this point, emphasize women and the land. But yeah, Liz helped me come up with the title. I think that Elizabeth Cook-Lynn is often known as this academic scholar, this political scholar, but she’s this really amazing writer who has taken the Oceti Sakowin oral tradition and reimagined it in a more modern form as print literature. When Elizabeth Cook-Lynn published her first novella, From the River’s Edge, it was critically panned by Western critics. They said the characters were unbelievable, “these aren’t really Native characters.” She has a strategy where she includes stories within stories, which is very much part of the oral tradition, right? We never say anything just in this linear, direct way, we always have stories within stories. She would try to incorporate that into her work and they would disregard that as an inexperienced writer, a number of different things she was criticized for. So her book was initially critically panned and fell out of print really quickly after it was published by the University of Colorado Press, and is actually out of print today.

What I do in the book is I analyze this collection of stories really closely and I show that her book is very much based on oral tradition. She’s retelling stories about the Corn Wife, who was another really powerful figure in the oral tradition that was entirely ignored by the missionaries. They never translated anything about the Corn Wife, even though she played a significant role in our culture. They never translated anything about the Corn Wife, but Cook-Lynn goes back and retells stories about the Corn Wife and how important she is to our culture and community. She argues that if we’re going to decolonize, if we’re going to overcome the matriarchal-patriarchal shift, we have to remind ourselves about the Corn Wife and the lessons that she taught us. I feel like Cook-Lynn does that in her book. She reimagines this oral narrative about the Corn Wife as a modern Dakota woman who’s living with the effects of the US-Dakota War, who’s living with the effects of the dams that were built in South Dakota and completely ruined the reservation. This woman, Aurelia, who’s a modern version of the Corn Wife, she’s re-teaching the community how to live in this new colonized, culturally suppressed environment. I think Cook-Lynn does an amazing job of doing that.

But like I said, a lot of critics initially panned the book. They said it just didn’t make sense, she was an experienced writer. So I go back and I show how the content, the style, the structure of the story is all based on the Oceti Sakowin oral tradition. One of the things I really attempt to highlight in this book, again, is that we have this really rich intellectual tradition that has existed for 200 years, it’s just that non-Native society has never recognized it as such. I really wanted to make that point in this book. We do have this rich literary tradition.

AA: Well, that really came through. And like I said, it included whole concepts that I’d never even thought of in any context, as well as just fascinating history. I enjoyed it so, so much, and I want to thank you so much for your book, for all your work, and thank you for a wonderful, enlightening conversation today. I’m so grateful to have had you on the podcast. Again, Dr. Sarah Hernandez, thank you so much for being here.

SH: Thank you for inviting me. Nice talking with you.

it’s not just a plot change

it’s an ideology change

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!