“I would not like to have to obey another.”

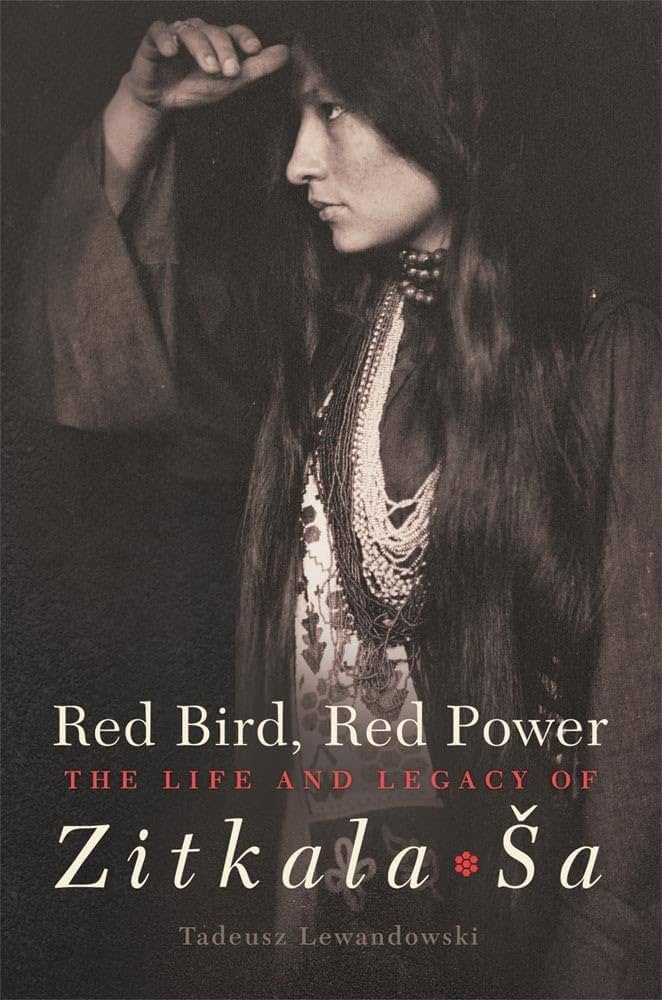

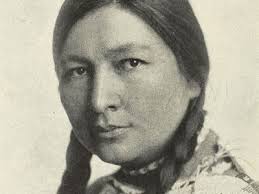

Amy is joined by Dr. Julianne Newmark to discuss the book Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkala-Ša by Tad Lewandowski and dive deep into the story of author, activist, and artist Zitkala-Ša.

Our Guest

Dr. Julianne Newmark

Dr. Julianne Newmark is the Director of Technical & Professional Communication and Assistant Chair for Core Writing at the University of New Mexico. As a researcher, she focuses on usability/UX/UCD and TPC pedagogy. She also teaches, conducts research, and publishes in Indigenous Studies, particularly concerning early-20th-century Native activist writers’ rhetorically impactful bureaucratic writing, particularly in Bureau of Indian Affairs contexts. In recent years, she has received multiple grants to fund archival research for this project, including grants from CCCC/NCTE and the American Philosophical Society. Her second monograph is provisionally titled “Reports of Agency: Retrieving Indigenous Professional Communication in Dawes Era Indian Bureau Documents.” Her 2015 book The Pluralist Imagination from East to West in American Literature was published by University of Nebraska Press. She is Editor-in-Chief of Xchanges, a Writing Studies ejournal.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Today we’re going to start with a story that will take a couple of minutes to tell before I introduce our guest. The story is told in the book Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkala-Ša by Tad Lewandowski. “In the early spring of 1896, a young woman from the Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota ascended the stage of the English Opera House in Indianapolis to represent Earlham College in the 22nd Annual Indiana State Oratorical Contest. She assumed that she had very little chance of winning, but still she spent the night before rewriting and reformulating her thoughts. During her harried last-minute alterations and the racial slurs she heard shouted at her as she took the podium, she delivered a remarkable speech. ‘America is a nation of free men and free institutions,’ she said. ‘Among its rivers, mountains, and lakes, in its stately forests and on its broad prairies, millions of toiling sovereigns have established gigantic enterprises, great factories, commercial highways, and have developed fruitful farms and productive mines. The ennobling architecture of its churches, schools, and benevolent institutions, its municipal greatness, keeping pace with social progress, its scholars, statesmen, authors, and divines giving expression and force to the religious and humanitarian zeal of a great people. All these reveal a marvelous progress.’ Yet, just as soon as she had constructed this triumphant vision of America, the young woman erased it.

‘But see,’ she entreated, ‘the tide of time rolls back 400 years. The generations of men of all nations who have developed this civilization in America return to the bosom of the old world. Myriad merchantmen, fleets, and armaments shrink and disappear from the ocean. The Fleet of Discovery, bearing under the flag of Spain, the figure of Columbus, recedes beyond the tractless sea. America is one great wilderness again. They heard the Great Spirit’s voice in the wind, frown in the storm cloud, and smile in the sunbeam. Magnanimous by nature, they welcomed their eventual persecutors. The invasion of his broad dominions by a paler face brought no dismay to the hospitable Indian,’ the young woman reminded her audience. ‘Yet this fraternal attitude could not be sustained. Civilization had brought vice, alcohol, and broken treaties, fueling the red man’s degradation and forcing him into pure desperation. The white man’s bullet decimates his tribes and drives him from his home. What if he fought? His forests were felled, his game frightened away, his streams of finny shoals usurped. He loved his family and would defend them. He loved the fair land of which he was rightful owner. He loved the inheritance of his fathers, their traditions, their graves. He held them a priceless legacy to be sacredly kept. He loved his native land. Do you wonder still that in his breast he should brood revenge when ruthlessly driven from the temples where he worshiped? Do you wonder still that he avenged the desolation of his home? Is patriotism only a virtue in Saxon hearts?

Let it be remembered, before condemnation is passed upon the red man,’ she continued, ‘that while he burned and tortured frontiersmen, Puritan Boston burned witches and hanged Quakers, and the Southern aristocrat beat his slaves and set bloodhounds on the track of him who dared aspire to freedom. Therefore, the so-called ‘barbarous Indian’ had brought no greater stain upon his name.’ Then, in a change of tone, the young woman again invoked the virtue of the United States, asking, ‘If the United States had entered upon her career of freedom and prosperity with the declaration that all men are born free and equal, how then could consistent Americans refuse equality to an American people in their struggle to rise from ignorance and degradation? Indians could only endure with the aid of an enlightened people bound by the obligation of a brother’s keeper.’ She closed her speech by imploring a beneficent government to extend an olive branch of peace.

‘America, I love thee,’ she stated. ‘Thy people shall be my people, and thy God, my God.’ As the young woman spoke her final words that day on the stage of the English Opera House, quoting from Ruth 116 in the Judeo Christian Bible, her dream of human dignity and unity within one nation was greeted with applause. But, as she lifted her head to survey the auditorium, her eyes fell upon a large white banner unfurled by students from a rival college. It displayed the crude caricature of an Indian squaw, rudely captioned with the word, ‘Humility’.” Today we’re going to learn about Zitkala-Ša, also known as Gertrude Bonnin. And to teach us about this incredible woman, I’m excited to welcome to the podcast Dr. Julianne Newmark. Welcome, Julie!

Julianne Newmark: Thank you! I’m really excited to be here.

AA: What we normally do is I’ll read your professional biography first, and then we’ll have you introduce yourself a little bit more personally after that.

JN: Sounds good.

AA: Julianne Newmark teaches technical and professional communication at the University of New Mexico. She publishes, teaches, and conducts research in an area of indigenous studies that concerns early 20th century native activist writers’ rhetorically impactful navigations of bureaucratic writing conventions, particularly in the Bureau of Indian Affairs context. We’re going to unpack that in a minute. She received a two-year grant for her book project, Reports of Agency: Retrieving Indigenous Professional Communication in Dawes Era Indian Bureau Documents. Her 2015 book, The Pluralist Imagination from East to West in American Literature was published by University of Nebraska Press. Newmark is also the editor in chief of Exchanges, which is a writing studies e-journal. That’s a fascinating bio, and Julie, let’s unpack this not only because it’s interesting about you, but because I feel like some of these concepts that you study and research will be really important foundations for our conversation today. Can you tell us a little bit more about the work you do as a writing teacher that studies Native American writing? And also maybe define what’s the Bureau of Indian Affairs for people who don’t know?

JN: Sure. I first want to acknowledge that I am on the tribal homelands of Sandy Pueblo here in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and I also want to acknowledge the Indigenous scholars whose work is far more important than mine on this topic. As a non-Native woman, I really want to position myself relative to these larger conversations in these familial relationships. I’m going to do my best to honor those traditions and the knowledge that is accumulated over time about “Red Progressives” like Zitkala-Ša/Gertrude Bonnin.

I am the director of the technical professional communication program at UNM. I have a very eclectic background, but what the monograph that you were referring to relates to is these bureaucratic documents within the Bureau of Indian Affairs during the Dawes era, so that was the late 19th century through the first third of the 20th century. The Bureau of Indian Affairs is a component of the Department of the Interior. Up until the middle of the 19th century, the Indian Office was part of the War Department, and then it was later moved into the Department of the Interior, where it still exists today. In the period of time that my research focuses on, the Indian Bureau – it was referred to as the Indian Bureau at the time, not the Bureau of Indian Affairs – managed Native properties, funds, and many other aspects of Indigenous life in the United States. It was a huge bureaucracy. As a teacher of technical and professional communication, I’m really interested in the way people write in the workplace, and this is a huge context in which Native people were writing in the workplace. And it hasn’t really been examined as a context in which a huge number of Native people were employed by the government and were sometimes doing really mundane kinds of writing tasks, but were sometimes doing much more complicated writing tasks, like the writing of annual reports or transactional communications.

Cathleen Cahill, who’s a professor at Penn State, who used to be at UNM, she’s written about this large bureaucracy itself, as have other scholars, many of them women scholars like myself. The point that my research is focused on, I’m interested in bringing forward indigenous voices within this vast U.S. government archive. Record Group 75 is the particular place within the National Archives where this work lies. So I do a lot of archival research, which is interesting. It sort of makes me a technical communication historian in a way, even though my training is in American literary studies and the teaching of writing. That’s a little bit of a background on what I do. I’m happy to tell you more about how I got where I am and how my interest was piqued into these texts, but that’s a good place to start, I suppose.

AA: Yeah, well, that’s the exact question I was going to ask you. How did you come to do the work that you do? How did you get interested in this?

JN: When I was in graduate school in Detroit, Michigan, I was introduced to Zitkala-Ša, like many people in literary studies programs, through her American Indian Stories, which was published in 1921 as a combination of essays that she published earlier in 1900 and 1901. I was introduced to it in a class by my professor Dr. Ross Pudeloff, who was really amazing. I wrote my seminar paper in that class on the multiple valences of discourse and rhetoric that she used in some of those essays, and it was my first publication. So this has been a very long time since that happened, I think over 20 years. So, that was my first publication. Since then, I’ve published a few other articles on her and then a chapter in my book, The Pluralist Imagination, is about her and Charles Eastman, who was another very important figure in the society for American Indians and otherwise. I mean, his legacy is very important.

My first job as a professor was at New Mexico Tech, and I was directing the writing program there. I kind of started to connect my experience in public relations and engineering communication, which existed before I went to grad school, to my pedagogy at New Mexico Tech, when I was teaching some technical writing. Eight years later, I moved to the University of New Mexico after having been an associate professor at New Mexico Tech. And then I was really much more immersed in technical communication and professional communication. I started being rather troubled about the opacity surrounding all of this writing that existed in the archives. Archives themselves, as I’m sure you know, are a really complex and fraught colonial domain, much like museums.

how then could consistent Americans refuse equality to an American people in their struggle to rise from ignorance and degradation?

AA: Yeah, do tell us a little bit more about that. How are archives a colonial space? And what do you mean by opacity? Tell us more.

JN: There are a lot of reasons why archives are opaque. In order to search our National Archives, of course, they belong to the people. We can do an advanced search on the web interface that the National Archives has, and it’s actually getting better and better. Many of those archives have been digitized, but the vast majority have not. And this goes for anything related to the U.S. government. This can be personnel records for members of the military, indigenous or not. I’m not just speaking to the way that these records relate to indigenous people. But there are U.S. government archives that are housed in these edifices that kind of convey an official government space. I’ve done a lot of my research in Kansas City, in Denver at the Broomfield branch, and at the St. Louis archive. And, I mean, they express this official sensibility about them. You have to be authorized as a researcher. You don’t have to be a professor, but you have to go through this training in order to get your research card. It’s a really protected space, you have to check all your belongings into a locker and you go in, all you can have is a pencil or your laptop and your scanner. They check everything on your way in and they check everything on your way out. It’s a really policed space.

And if you think about that in your head as this reflection or iteration of the way that bodies and information and stories have been policed over time, especially in my work related to indigenous people in the United States, you can understand how many people are very troubled about the protected ways in which their family’s information is held in these U.S. government spaces. So that’s a thumbnail sketch of that. And that should make sense to your listeners as it relates to the way that indigenous traditional objects and family belongings have been removed from communities and put in museums over the last several hundred years. The famous example in the British Museum about the Elgin Marbles, for example, is another way in which these important historical objects under the auspices of imperialism and colonialism have been extracted from their home communities and put in these institutions that connote an official way of arranging a story to make sense within the imperial narrative. So, archives are part of that. And especially when you think about the way that Native American histories are largely oral historically, and this is not to diminish the really important ways that Native people have been telling their stories in print, or in song, or in rich media formats, or in fashion, or whatever it may be. But I just want to make these connections for your listeners to explain how, as researchers who work in Indigenous spaces, we have to be really sensitive to those realities.

AA: Mm-hmm. That makes a lot of sense. Backing up, maybe you could answer this question quickly, but you did mention that you yourself are not a Native woman, you’re a white woman, so am I. What got you interested in general in studying these topics?

JN: So, my book is about the ways that various kinds of marginalized people have navigated American national identity, particularly from the late 19th century through the first third of the 20th century. And I look at many different communities and one of the chapters, as I said, is on Eastman and Gertrude Bonnin, otherwise known as Zitkala-Ša. I grew up in New Mexico, so I was raised in a context in which Native American presence was constant, and normal, and regular, and all of the different histories in my state are very apparent to anybody who lives here. Native voices have always been really important in New Mexico, as have Mexican-American, Chicano/Chicana histories. It is a myth that there is this tricultural harmony in our state. I think that’s been used in a sort of oppressive fashion to flatten out the discord between these communities over time, but it is true that this is a tricultural state, largely.

And because of that, I was really interested in learning more about Pueblo and Diné history in my state, which is not the state where Zitkala-Ša is from, but nevertheless, my interest was piqued in that fashion as a result of the place where I was from. I think that some of these pan-Indigenous vocalizations suggest that there’s a kind of similarity across all tribal communities. And there certainly are commonalities, you’ll see that in the Gathering of Nations that happens here in Albuquerque, where lots of tribes come together in a celebratory fashion. But I’ve also come to better understand the really important differences between sovereign nations through the over 20 years that I’ve been working in this field. That’s a little bit of a backstory about why I was interested in this work.

AA: Perfect, thank you for that. Well, let’s dive into the life and times of Zitkala-Ša. The book that we’ll be discussing is called Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkala-Ša. Can you tell us briefly who wrote it? What’s your review of the book? And then we’ll dive into the lay of the land, the time period and the location, and then we’ll get into her life.

JN: Sure. So this was written by Tad Lewandowski, a Polish-American scholar who tragically died a year ago. He was super prolific, wrote a lot about folks in this Red Progressive movement. My review of the book, I mean, I read a lot of academic book reviews and I was invited to review this because I’ve written a lot about her, about Zitkala-Ša. My review is very positive. This is the first comprehensive monograph about Zitkala-Ša. There have been lots of other books about her, different parts of her scholarly life and her artistic life. So, in terms of describing my review, I actually reread it this morning. I published it many years ago now. It was very descriptive about how the book is organized and some of the things that I think Ted did really, really well. It was exhaustively researched, which is incredible. That’s kind of one of his trademarks, is that he was a very precise, immersed scholar. Another thing that I noted in my review is that it is very chronological. That’s the way that histories are written, but that’s not necessarily in synchrony with the way Zitkala-Ša told her own story, the way some Indigenous storytellers tell a story of their community. But that’s sort of a product of squeezing into the academic publishing tradition a story that kind of exists outside of that tradition. So that is my review of this book, which has been, I think, really valuable for people. But I do want to mention that Ted’s book wouldn’t exist without the work of Jane Hafen, an Indigenous woman scholar herself. She’s written a lot on Zitkala-Ša, and this is one of her books about Zitkala-Ša that I just would love listeners to visit at their library or ask their library to order for them. It was published by Nebraska and it’s called Dreams and Thunder: Stories, Poems, and the Sun Dance Opera. There you go.

AA: Yeah, thank you. And you said that the author, her name is Jane Hafen, right?

JN: Yeah, P. Jane Hafen. First initial P.

AA: Perfect. Listeners should definitely check out her book and her scholarship, so thank you for highlighting that. Okay, let’s talk about Zitkala-Ša. Tell us the rough timeline, what time period are we in? What location did she inhabit? And what was going on between the white colonizers and Native communities at the time that she lived?

JN: She was born in South Dakota, she’s a Yankton woman. And I’ll say one more thing, in Jane Hafen’s introduction to this book she does an excellent job of really describing Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota linguistic histories, and she explains why she uses “Yanktons” when she’s talking about Zitkala-Ša’s home community. There are a lot of other Indigenous scholars right now talking about the Očhéti Šakówiŋ, the Dakota people, including Chris Pexa. He’s an Indigenous scholar who’s at Harvard currently. My colleague Sarah Hernandez at the University of New Mexico is also writing about Očhéti Šakówiŋ, the history and people and literary traditions, so I direct your readers to them as well. At the time when Zitkala-Ša was a little girl in the late 19th century, there was a lot of missionary presence among the Plains tribes. This was also in the Dawes period, the period of the Dawes Severalty Act, where there was a huge impact on Plains tribal land holdings. The goal was to break up tribal land holdings, community health holdings, into 160-acre individually owned allotments. One of the conditions of being allotted was that you had to exhibit that your family was living by Christian principles. One of those principles would be to get your children a Euro-American education. So there were lots of missionaries coming on to tribal homelands, encouraging children and encouraging their families to allow these children to go to boarding school.

Zitkala-Ša was kind of swept up into this movement as a little girl. Her last name at the time was Felker, that was her stepfather’s name. Later on, she changed it to Zitkala-Ša (Red Bird) herself through a somewhat complicated story that she explains herself in her autobiography. She gave herself this name, which means Red Bird. But as a little girl, she was taken to White’s Manual Institution in Wabash, Indiana on the train, and she tells this story very clearly in her autobiographical writings. The School Days of an Indian Girl is very well known for recounting those experiences. Some scholars today are referring to these essays as semi-autobiographical, which is sort of new to me, but I guess maybe anything is sort of semi-autobiographical when you’re telling it from a 20-year delayed vantage and you’re trying to make it very rhetorically impactful for the readership. I refer to them as her autobiographies, I’ll just say that.

So she moves away from home, she goes to this very strict Quaker boarding school. Her hair is cut, she’s disallowed from using her home language, and she’s inculcated in Christian, like, moralities and behaviors. If your listeners and you are very familiar with the boarding school story, you can assume how this went. One of the differences is that later on in her life, she retold these stories in a really powerful way, and that’s how she’s best known in American literary studies and in Indigenous literary studies, is for these autobiographical accounts. She does a little bit of back and forth between the “white world” of the boarding school and her home community. She goes back and forth some. And later on, she goes to Earlham College and she becomes a teacher at Carlisle, which is a bit ironic in that she herself tells of her traumas, having been a boarding school student herself. But then later on she makes a pretty dramatic break with Pratt’s ideology and she goes to the New England Conservatory of Music to study violin. It’s at that time, around the year 1899 or 1900 that she finds herself in this artistic world where there are women who are interested in amplifying her story. And she sort of gains entry into this literary space of the Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and she’s able to tell her story in autobiographical accounts. That takes us up to about 1902, and soon after, for various reasons, she returns to Yankton. She re-meets a childhood friend, Raymond Bonnin, they get married, and then they move to Utah because he’s employed in the Indian Service. He is then positioned at the Uintah Ouray agency, and that period of time while they are in Utah is really, really interesting to me. I’ve held three fellowships at BYU studying her papers, which are in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections at BYU. I’ll stop there for now. There’s so much of her story after that point, but I’ll just pause.

AA: Yeah, that’s great. That was a great way to introduce the main points on the timeline until then. I do want to drop down into a couple of those things, and I’d like to first return briefly to that speech that I opened with, because it was really interesting. I opened with that speech because it was such a vivid anecdote where so much was kind of present in that moment. The book talks about the reviews that were written in the paper, and to me, they seem to completely miss the point of the speech. Some of the reviews had titles like “Cheers for the Indian Maiden” and then they were supposed to have described her speech, but they described her appearance: her “copper color skin,” or “the slight dark-skinned girl,” and she was praised that she didn’t seem like an Indian with a quote that said, “Her voice was clear and sweet. Her language was that of a cultivated young woman, and her pronunciation was without a trace of a tongue unfamiliar with English. Her manner was real, womanly, and refined.” Oh, and then the last one, “Much better looking than the pictures of the average Indian.” So they gave her all this praise that she was, you know, not like the other Indians, and completely ignored the content of the speech. Is that pretty typical for the time? What are your thoughts?

JN: It is, it is. And I would like to connect this actually to the very title of your podcast, Breaking Down Patriarchy. Of course, we all understand that she was operating in a highly objectifying patriarchal time period on the cusp of these moments where women were gaining more power over their own stories. So she’s operating on multiple channels as a woman orator, as an artist, as a Native woman, as a kind of proto-feminist, perhaps. She’s often been categorized as this woman, and she uses this phrase herself, “hanging in the heart of chaos,” when she was neither an Indigenous girl or a white one. I know her life was very complicated and caused her a lot of personal and internal discord, but lots of people do for various reasons. So when you mention that the reviews totally missed the point, I’m absolutely not surprised that they totally missed the point. I think she didn’t miss the point. She was playing very much with those dynamics and she continued to do that for the rest of her professional life.

In her correspondence, which is in the special collections at BYU, she talks about when she’s invited to give a talk many years later, wearing her Indian costume. And, I mean, I don’t think “costume” was laden with the kinds of assumptions we have about it today. It was her outfit, but she did kind of deploy it as a kind of costume, strategically, tactically, for her audience, her Indianness, in order to hopefully move them politically so that they could advocate for the things she wanted them to advocate for, whether it was voting rights, whether it was the anti-peyote stance. So the fact that she was represented using these facets of sentimentality concerning refined womanhood and American white womanhood, the kind of angel in the house paradigm, it’s totally unsurprising, but it works within a strategy on the part of the writers of the reviews of trying to gain currency with their readership. Like, how are we going to make this woman understandable and likable to our readers? She later used those kinds of identifiers as a wedge where she’d be like, I will wear my costume, but then I’m going to hammer home these points that I want to make unmistakable. So she was not unaware of the way that she was going to be rendered, and in fact, she empowered herself through it throughout the rest of her life.

AA: That’s really amazing, Julie, because as I’ve started on this journey of learning more about American Indian history, one of the most tragic things to me is this no man’s land that this generation of Native youth and young adults found themselves in where they were like, she says it this way, “taken out of the teepee” where they grew up with their families when they were little in traditional ways of life, and then taken to boarding school and taught in the “Christianized,” the “white man’s way,” and then they come back to their communities and they’re too white to be able to be useful. They haven’t had the training in how to live a traditional life. They can’t live a traditional life anymore, but then they can’t enter white society because they’re too Indian for white society and too white for Indian society, and they find themselves in this gap where they don’t fit anywhere. That’s been one of the most tragic things to me, but it sounds like Zitkala-Ša actually, instead of having neither one, she claimed both. She was biracial, actually, wasn’t she? Her dad was white, I think, and her mom was Native. And she was able to, like you said, deploy and take on whichever identity suited what work she wanted to do and she used it very deliberately. Is that an accurate assessment?

JN: I would say so. And I don’t think we should lose sight of the fact that she was an artist. She was an artist with words, with music, with performance, with her political strategies. So it was very conscious on her part. I mean, maybe it was a kind of recovery or even therapy, to use really present-day lingo, that she tried to use these aspects of her life to create a kind of coherence around, as she would call it, the Indian cause. She really felt, and I’m not saying this flippantly, because I have like 240 pages of notes on her archives, these are her words, she was absolutely expending her energies and her life for the Indian cause. That’s her phrase. And later on in her life, through the National Council of American Indians, which was a bit ineffectual with some things, she poured so much effort into Native American education, education of adults in tribal communities, that was her passion. So, insofar as she was stuck between worlds, which is a commonly used descriptor, I think she recognized that a lot of people are, whether from her home community or from other communities. She had a lot of epistolary confidants from other walks of life. And I know that one of the questions you wanted to explore concerned her religiosity. I think she recognized that in that realm, there were a lot of people looking for answers, too, like she was, and a lot of the women who were her correspondents throughout her life were as well. So I don’t want to diminish her Native identity or selfhood at all, which was crucially important to her in her whole story, but she was looking for ways to connect with all kinds of other people strategically to get them to benefit Native people.

I will wear my costume, but then I’m going to hammer home these points

AA: Mm-hmm. Okay, let’s dig in a little bit more to her writings. And you, as a writing teacher and someone who studies rhetoric, I’m really interested to hear what you think. Like when she was in the phase of her life when she was writing Impressions of an Indian Childhood, The School Days of an Indian Girl, Old Indian Legends, what was the message of those writings and how was it received?

JN: Well, one of its most famous commentators was Richard Henry Pratt, who thought that she was very ungrateful for all that she’d gained through the education she received in boarding school and all the fame that she was receiving. In 1901, 1902, he kind of defamed her a little bit as an ungrateful person. But these essays are really very beautifully written. They combine some of the realism and sentimentality of that era, some of those linguistic or artistic strategies. My first article that I mentioned talks a lot about her strategic play with certain words that were highly coded in the Euro-American discourse, particularly the words “wild” or “savage” or “free.” She plays with them to make them mean what she wants them to mean. And some mean something good, something empowering and uplifting. She codes the word “wild” as a beneficial aspect of her own childhood, whereas to Euro-American Anglo readers it was generally used in print at the time as a cipher for savagery, which she absolutely refuted and seized upon herself. There’s a lot of biblical imagery, there’s a lot of imagery around telecommunications and industrialization and settlement. You can do a very close sort of deconstructive reading of these essays and understand that in very few words, she’s playing with a lot of cultural meaning.

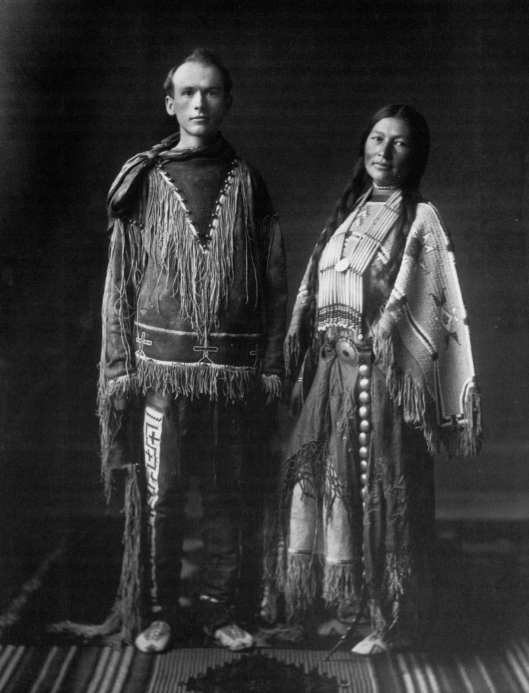

They did allow her to gain a lot of fame, but that didn’t come with much power as we would conceive of it today or financial benefit, which was very difficult for her and Raymond for the rest of their life. I was thinking about this and I wanted to mention it, one of your short videos to trad wives. I was thinking about something you said there about how it’s really important that we push against these versions of contemporary womanhood that recast the relationship as one in which the woman serves the man. The man also brings happiness to the woman’s life. You mentioned that point. She and Raymond had this marriage in which they worked so hard to lift each other up, and it is heartbreaking and beautiful to read all of their letters. I mean, when I was reading the letters that he was writing to people after she died, I felt like I was intruding on this very personal space. He was just devastated. But I wanted to get that out there that he is a really important part of her story, too. She could have married Carlos Montezuma and didn’t. She married Raymond Bonnin, and they worked together and he was her biggest champion as she was his. So that touches upon this idea that you raise, like, such a weird perversion of these domestic roles. And we see her grappling with that in her time, in the 1920s, in the 1930s, where she absolutely wanted to be the president of the National Council of American Indians on the letterhead, and Raymond was the secretary. But behind the scenes, they were very much collaborating on everything together, and I think that’s a really beautiful part of the story. And I’ve written a lot about him, too, and his part of this story. I was thinking about it last night, and I was like, “I think that needs to be included in this.”

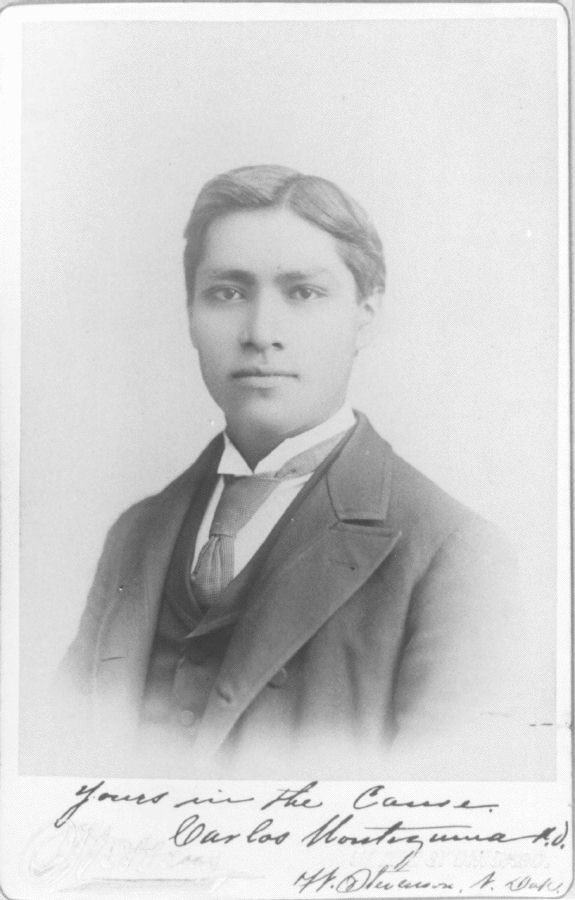

AA: I’m glad you did. I don’t know that I got such a strong sense of that in the book that I read, The Red Bird, Red Power. I don’t think that that was foregrounded very much. If anything, actually, I felt like that author focused more on her relationship with Dr. Montezuma, and I wanted to touch on it. So for listeners, we’re going to back up because before she married Raymond Bonnin, she was very seriously dating and involved with Dr. Montezuma. In fact, they were engaged to be married.

JN: They were. And the letters around the ending of the engagement and the return of the engagement ring are really highly charged, emotionally. I had a fellowship at the Newberry library many years ago, and they have Carlos Montezuma’s papers. And I will mention an excellent recent biography by David Martinez, a professor in American Indian Studies at ASU. What an amazing scholar. He just published a biography of Carlos Montezuma, so he covers their relationship in that book minimally because the rest of Carlos Montezuma’s story apart from her is fascinating and really important. So Zitkala-Ša and Carlos Montezuma would have been sort of this Red Progressive power couple had they been married, but they did not get married. At the end of the engagement, she went back to Yankton. I mean, she believed that it was in her home community that she really needed to serve. She reconnected with Raymond there, and as I mentioned already, soon after they were married, they moved to the Uintah Ouray Agency in Fort Duchesne, Utah, and lived there for many, many years, over a decade.

AA: Sorry, I do want to back up, though. I want to talk about Dr. Montezuma because this was a really important thing to dig into in terms of gender. Because the reason I feel like she broke off that engagement was because he was expecting her to take a secondary role.

JN: Yes.

AA: As women were expected to do at the time, and she refused. There are quotes from her letters: “I am too independent. I would not like to have to obey another. Never!” Right? And she’s challenging the Indian rights organization that they’re going to work for, and she writes, quote, “I do not understand why your organization does not include Indian women. Am I not an Indian woman as capable to think on serious matters and as thoroughly interested in the race as any one or two of your men put together? Why do you leave us out? Why?” That’s a whole direct quote from her letter. She’s mad! And I think they loved each other a lot, but she would have been expected to be in a more proper early 20th-century subjugated role, it seems like, and she just wouldn’t do it.

JN: Right, that’s all absolutely true. And she had such a This is so biographical, but she reminds me a lot of my grandma Rose just in that she was not going to abide by the conventions of her time in like 70 percent of the ways, but in 30 percent of the ways she absolutely wanted to. To Raymond, she was really interested in certain aspects of domesticity and being a mother and caring for her grandchildren and those kinds of things. That does not fly in the face of her autonomy or her feminism.

AA: Yep. It shouldn’t.

JN: Yeah, and it shouldn’t, right? Vis-a-vis Montezuma, you know, he did want her to move to Chicago where he had his medical practice. He did end up marrying a woman and she was absolutely his helpmate in the fashion that we’re used to thinking of. And that’s not to diminish that wife, she was beloved by Carlos Montezuma, cherished, celebrated, and really helped him in his life, and I’m sure he supported her. I don’t know as much about their relationship as I would like. But yeah, when Gertrude Bonnin, Zitkala-Ša, was a young woman and she was engaged to Carlos Montezuma, she was not going to have her goals subsumed beneath his. And she didn’t. So when she and Raymond moved to Utah, she definitely tried to carve out a space for herself to do important work among the Ute people. And then when she took a leadership role in the Society of American Indians and they moved to Washington, D.C. in the 1910s, it was so that she could further that part of her activism. And Raymond at the time was moving in a different direction. He ended up getting a juris doctorate. He did not sit for the bar, but he worked in the law field for the rest of his career. So it was advantageous to them both to a degree to move to D.C. But most people know her for her 1900, 1901, 1902 autobiographical writings, but they were later published in 1921 as a collection. And that coincides with this second flowering of her importance when she’s in D.C. and she’s speaking before Congress, and in 1926 she’s creating the National Council of American Indians. I mean, that is such an important political period of her life.

AA: Mm-hmm. Well, let’s get into the D.C. period in a minute, but first, let’s go back to the Utah period, because that was so interesting. I had known just a little bit about Zitkala-Ša, honestly, just because she comes up in photographs all the time because she was so beautiful. She was photographed a lot, so I’d seen her like on the internet as like “most beautiful people from the 19th century.” I didn’t have any idea she had a Utah connection until I read the book. But they lived, like you said, on the Ute and Ouray Reservation, and then she was involved in all kinds of art and cultural projects. Can you tell us about those projects and specifically about the opera she wrote, which debuted in Utah? It’s so interesting.

JN: Vernal, Utah, I think is where it debuted at the opera house. And this is an area where Jane Hafen is absolutely an expert because of her graduate studies in music and being the first person to really go through those papers when she was doing her doctoral work. So while Zitkala-Ša was in Utah, she was trying to found a community center for Ute people to learn some domestic arts, to have a reading room, to just have this space at the agency headquarters. And I think she felt a little isolated in terms of her artistic opportunities. She was, as has been established, a powder keg of energy, lots of goals and dreams. I mean, very relatable, I think, to women of our era. So she and Raymond met William Hanson, who was her collaborator on The Sun Dance Opera. They had seen a Ute Sun Dance, and of course the Sun Dance was practiced by other tribes as well, but as Jane Hafen emphasizes, it was not practiced in Gertrude and Raymond’s home community. So they have this sort of amalgam version of The Sun Dance Opera.

Gertrude was trained classically as a violinist, so she collaborated with William Hanson on this opera, and it debuted in Vernal, Utah. And then the year of her death, it premiered in New York City, so she didn’t get to see it. It was like the New York Opera Guild or something that premiered it, and today we would look at it as probably a highly fetishized version of Indigenous song and dance and representation, and the lead roles were performed by classically trained Anglo-American actors and her role in the New York City production was super marginalized. She was only mentioned in the show notes in the program and Hanson’s name was front and center.

AA: Wait, wow. I did not realize that. That’s crazy. Oh my gosh.

JN: Yeah. When it was performed in New York, when she died, things had already been ramping up for its premiere in New York and there was a hope that she would go. So she was trying to express some of her artistic ambitions via this opportunity that seemed to appear to her, which was this collaboration. And William Hanson was really interested in all of this material. And again, this is where we would really want to defer to Jane Hafen. To my reading, it didn’t seem like Gertrude was feeling like the story, The Sun Dance Opera, was being constrained by a Euro-American lens. I feel like she felt at the time that she had a really important role in bringing this story forward. But that was all. There was nothing of that size or scope that she ever created in the artistic sphere after that time. And there have been a lot of questions about, “Well, why not?” And it was because her political activism really took up all of her energy.

AA: Yeah. Let’s talk about that. And that can be where we close out the episode, because she did so much important work politically. And again, I just want to emphasize at least the impression that I got from reading this and from a few additional readings about her, I feel like she was presented, again, because of her position as a biracial person and being able to exist pretty successfully in both worlds – I mean, really remarkably successfully in both worlds – that she chose to constantly do that bridge-building work of making one world legible to the other. To make them understandable to each other, and then to use her access to the white world to do work to elevate Native communities. And actually, she was quite radical, and that was, like you mentioned before, when she was writing these things where Pratt and others just called her ungrateful. “How can you criticize us in this way?” They kind of expected her to comport herself within the white world as like playing by the white rules, and she often didn’t, right?

JN: No, no.

AA: She was very, very progressive. That just really struck me. She was much more of a radical than sometimes people will remember her as, at least that’s my impression.

JN: Yeah, and that’s been a bit frustrating to me and I think some other scholars in that some people are very critical of her assimilationist bent, some scholars in Indigenous studies. But there are people who, as I was saying, Chris Pexa, Kiara Vigil of Amherst, Cristina Stanciu, another non-Native scholar who has a recent book that discusses Zitkala-Ša. There are people who don’t necessarily fault her for what may be perceived as her assimilationism. Because it’s understood in the larger context of her time and the work that she was doing. She still can be studied and understood as an important member of the Society of American Indians. And there was a wonderful hundred-year celebration, I think it was in 2011, at Ohio State, and two special issues of I think American Indian Quarterly and Studies in American Indian Literatures, and I have a chapter in this double issue. But people came together to celebrate the important work of all the members of the Society of American Indians on its hundredth year anniversary. So, like anybody, her story was really complex.

she was really interested in certain aspects of domesticity and being a mother and …that does not fly in the face of her autonomy or her feminism.

And to connect to your questions about that work that she was doing and her facility in existing or working in different communities, she did spend the rest of her life outside of the D.C. area in Virginia and would travel. They would take long car trips, she and Raymond, in the summer to go back home, to travel to tribal communities. It was difficult work because she felt like all of her expertise that she had gained being what some would call a transcultural communicator, was not so much appreciated back home. That was frustrating because she did see that people were living in great poverty and she was hoping to help move that dial in some important way. Almost like she had gone through all this pain in her own life and she was hoping to put it to some good, and she and Raymond were incredibly financially strapped at the end of their life. A lot of the letters were about hoping Raymond gets the Ute contract to represent the Utes in Washington, D.C., and it was like this constant waiting for him to get this, or that she would get little royalty payments, and those would be really important to them. They were supporting her son, and two of his children were living with her, so it was not an easy life for her.

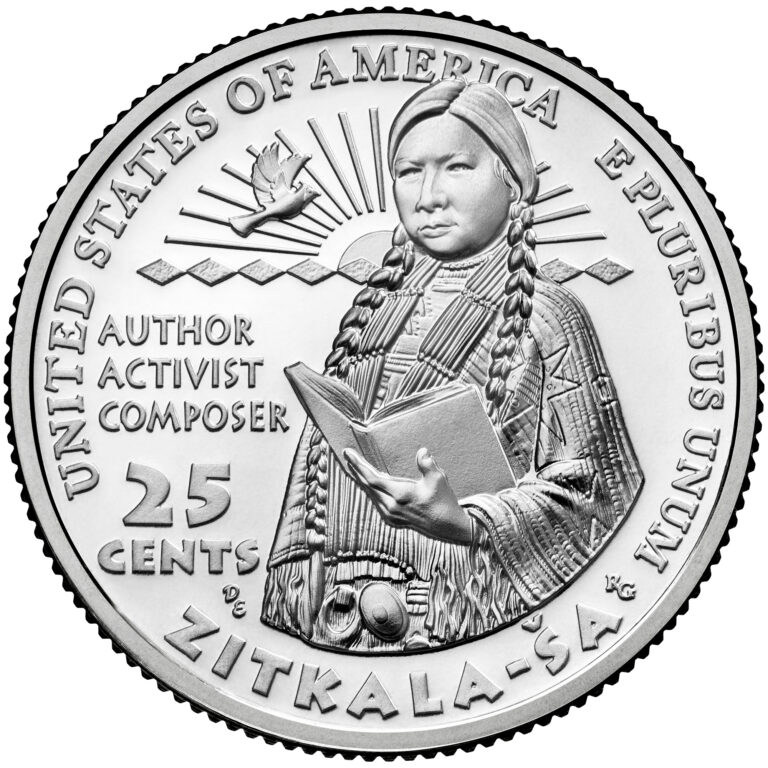

I want to just mention that in recent years, as we know, she’s become really well known. She’s on a quarter, it’s a beautiful coin. And the Diné composer, Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, Raven Chacon, has a piece for Zitkala-Ša, which is in the Whitney Biennial. So, she’s in the public consciousness, and Indigenous artists like Chacon bring awareness of her to ever new audiences and sort of the avant garde art world as well. So she has this really interesting afterlife, and it’s about family to her and relationality and really trying to form these networks. Almost like a net that’s going to be protective and uplifting at the same time, and that’s what she was hoping the National Council of American Indians would do. But it was a labor of love that exhausted her and maybe didn’t have the political power that she was really hoping that it would have. But I’ve studied a lot of the materials that she composed in that era. They’re less interesting on their face as the autobiographical writings, but as somebody who teaches professional technical writing, I’m always really interested in how these business documents come together. What are the design choices? What are the rhetorical choices that she made, and why, to reach the goal that she was trying to reach?

AA: And can you tell us quickly what those goals were? I know that one of the biggest things that she was fighting for was citizenship so that Native Americans would have the right to vote, right? That was a huge marker. What were some of those things that she was fighting for and how was she fighting for them?

JN: Right. With the Indian Reorganization Act, she was very well connected with John Collier. They had kind of an up and down relationship. There’s a lot of correspondence between them as well. She’d known him for a long time. Through the National Council of American Indians, she was trying to encourage local indigenous people in their home communities to set up these chapters. And these chapters would facilitate the communication of important political information from Washington, D.C. to local chapters. She would write up a newsletter, send it to the chapters, they’d have a meeting, they would discuss these political developments, and she thought that there was a huge lack of knowledge. Again, to return to the term I used at the beginning, opacity between everything that was happening at the level of the Bureau of Indian Affairs vis-a-vis Native peoples’ powers, money, rights, lands. And she wanted to insert herself into that space to help be the conduit of information. And of course, Carlos Montezuma wanted something similar. He had his newsletter, Wassaja, that he self-produced for many, many years in order to communicate the message that he thought was important to communicate. But she wanted to do this through her Indian newsletter, which never really took off, and these local chapters never really took off.

One of the things you see in her archives are all these like solicitations for membership, like these little membership cards. She was applying for grants, like one from the Russell Sage Foundation, which is a really interesting document in her archive that tells her story and Raymond’s story, and they’re trying to collect funds to distribute for the protection of Indigenous crafts and traditional artistic practices. So she was trying to use the NCAI as this hub of education, information, and preservation of traditional life, ways, and crafts. But she was at this pivot point between wanting indigenous people to benefit from all kinds of modern technologies, she mentions typewriters and airplanes. She doesn’t want them to be confined to some sort of antiquated past where she wants to preserve traditional artistic practices, but allow people to avail themselves of the benefits of industrial modernity. And that’s clear in her archive, for sure, to me, at least as a researcher.

AA: Wonderful. Well, thank you, Julie. This has been so informative and so illuminating. Is there anything that you’d like to share just as we wrap up as a final takeaway?

JN: I just want to invite listeners to read more about Zitkala-Ša and her history as well as other members of the Society of American Indians. I’d like to direct people to the work of some Indigenous theorists and literary historians and scholars like Chris Pexa and Kiara Vigil and Sarah Hernandez. I absolutely want to direct people to their work, and I again want to acknowledge the land where I am working from adjacent to San Diego Pueblo here in Albuquerque, New Mexico. And I want to thank you, Amy, for this podcast, which is super interesting. I hope people are inspired to read more about these important historical figures as a result of listening today. So, thanks for that.

AA: Hear, hear. I agree. So many great things to read, and we’ll have those in the show notes on the website. You can check out social media for more ideas and ways to learn more. Again, Julie Newmark, thank you so much for your work and thanks for being here today!

JN: Thank you very much.

much more of a radical

than people will remember her as

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!