“I feel like with this revitalized ceremony, we have changed the world.”

Amy is joined by Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy to discuss her book We Are Dancing For You as well as the violent legacy of settler colonialism in California and how Indigenous women are reclaiming their traditions.

Our Guest

Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy

Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy is an Associate Professor and Department Chair of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University. Her research is focused on Indigenous feminisms, California Indians and decolonization. She received her Ph.D. in Native American Studies with a Designated Emphasis in Feminist Theory and Research from the University of California, Davis and her M.F.A. in Creative Writing & Literary Research from San Diego State University. She also has her B.A. in Psychology from Stanford University. She has published in the Ecological Processes Journal, the Wicazo Sa Review, and the Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society journal. She has also published creative writing in the As/Us journal and News from Native California. She is also the author of a popular blog that explores issues of social justice, history and California Indian politics and culture.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: As many listeners know, I spent fifteen years of my life in Northern California. Two of my kids were born there, and honestly, no matter where I live for the rest of my life, it’s my favorite place on earth. And if I can figure out how to be buried under an oak tree in Rancho San Antonio in the Los Altos Hills, then that is where I want to be. So Northern California really does feel like home to me. And yet, one day, as my daughter Lindsay and I were taking a walk along the oak and eucalyptus lined streets by our home, she started talking about some indigenous North American authors that she was reading in high school. And she started to cry, and she said to me, “Mom, we live on stolen land.” And I remember exactly where I was standing when she said that. It wasn’t that I didn’t know that, I had always felt really sad and I felt conflicted, for example, when I was little I read the Little House on the Prairie series. And I learned a little bit of Native American history in classes here and there as I grew up in Colorado.

But when Lindsay said it like that, “we live on stolen land,” for some reason, everything shifted for me. And our family began talking about it a lot and asking questions specifically about the original occupants and inhabitants of the land that we were then living on. Thankfully my kids had learned more than I had learned as a child. They learned about the Ohlone tribe during their California history units, but these units also kind of glossed over those topics and mostly talked about the California mission system, the rancho system, and the gold rush. And really for all that we could tell, where we lived all traces of indigenous lives and culture were gone as far as we could see when we were talking about it. And to my knowledge, we didn’t know any Native American people there in the heart of what has become known as Silicon Valley.

So, when I saw the title of the book, We Are Dancing for You: Native Feminisms and the Revitalization of Women’s Coming of Age Ceremonies by Cutcha Risling Baldy, I knew I wanted to read it. But I didn’t know that it was about the indigenous people of Northern California, not the Ohlone where we lived, but farther North, the Hoopa Valley tribe. And I want to start this episode with a quote from the book as we begin.

“Our histories as indigenous peoples in California are real, lived, and continuing, yet not enough people know about what happened in California. There are no public memorials to the hundreds of thousands of people killed in order to claim their land, their children, their homes, and their resources. History books erase the brutality of the missions, rancho system, and gold rush.”

And that hit me deep. And I can attest from personal experience, having had kids grow up there, that is true. And this book opened my eyes not only to the past, but to an incredibly hopeful and beautiful vision of the present and future in indigenous lives. I am so grateful I read it and I highly recommend to listeners that you buy it. And I’m thrilled to welcome to the program today the author of this book, Cutcha Risling Baldy. Thank you so much for being here, Cutcha!

Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy: Thank you for having me.

AA: I’ll start out by quickly reading your official, professional bio and then you can introduce us to you a little more personally. Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy is an Associate Professor and Department Chair of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University. Her research is focused on indigenous feminisms, California Indians, and decolonization. She received her PhD in Native American Studies with a designated emphasis in feminist theory and research from the University of California, Davis, and her MFA in Creative Writing and Literary Research from San Diego State University. She has her BA in Psychology from Stanford University, and she has published in the Ecological Processes Journal, the Wíčazo Ša Review, and the Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Journal. She’s also published creative writing in the As Us Journal and News from Native California. And she’s the author of a popular blog that explores issues of social justice, history, and California Indian politics and culture, which can be found at cutcharislingbaldy.com/blog.

So again, I really recommend that listeners check all of that out. Dr. Baldy, I was also going to read the next section about your background and your affiliation with the tribes in Northern California, but I’d actually love you to tell that part of your story yourself. Can you tell us where you’re from, a little bit about your family, and what has brought you to the work that you do?

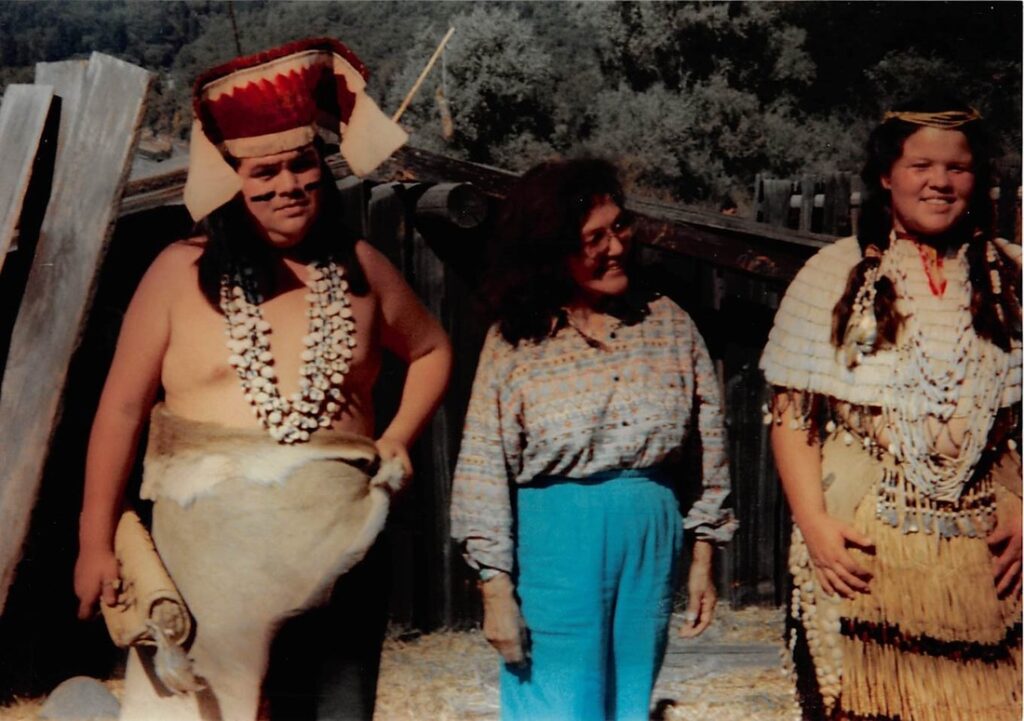

CRB: Yeah, of course. He:yung, kileh. Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy ‘a:whólye. I am Cutcha Risling Baldy, I’m Hupa, Yoruk, Karuk and enrolled in the Hoopa Valley tribe. They’re the three largest tribes in Northern California, and I was born and raised in the Goudi’ni area of Wiyot Territory, which is out on the coast about an hour and a half from our reservation. Regular people drive it, but when we drive it, it takes about 45 minutes. That’s what we always tell people. Our reservation is located somewhat inland in our aboriginal territory. I think what’s really beautiful about the Northern California region, the far Northern California region, where they say we live behind the redwood curtain, is that most of our tribal peoples in this area are still in their aboriginal territories.

I grew up in the aboriginal territory of the Wiyot peoples, that includes the Bear River Rancheria, the Blue Lake Rancheria, and the Wiyot tribe. The Hoopa Valley tribe is still in their aboriginal territory. Our valley is where we say we came into being, it’s where the world was made, and then we were made from the space there. And you get a real sense up here of the fact that we have our unbroken connections to land and culture and ceremony. And I think that has been really powerful to grow up in a space with the peoples of this region and to really learn from indigenous knowledges in a place that we have very, very long connections to. I went to school here, graduated from high school here, then went to college. I think my ultimate goal in life was always to return home. It was really important to me that we were able to continue to grow the future generations of people that wanted to work and do ceremony and cultural practices.

And so in about 2009, I founded a nonprofit organization with one of my very good friends called the Native Women’s Collective. And our goal was to create a supportive space where we could help to revitalize Native arts and culture practices and really support people who have been doing that work. I think that our area has always been really a powerful place for people because it’s demonstrative of indigenous peoples constantly trying to make sure that we were carrying on our culture and our practices, but also really thinking about what that meant for the future of not just us, but the whole planet all together. And now I live here in the spaces where what they say is that the river that runs through our valley. It builds us, it’s like the water that runs through our veins, it’s what made us into the people we are.

And I’m able to really connect the work that I do in academia with the work that I want to do in my communities, and empower, hopefully, all peoples to be able to say that there’s work that we can do to make sure that we’re pushing back against a settler colonial system that would have us believe that there’s nothing beyond colonialism and capitalism and patriarchy. As if there’s no way to actually build a world where we can all breathe and drink the water and feel safe. And I think that indigenous peoples really are the peoples who have envisioned that from the very beginning. We’ve always been thinking about what’s the best world that we can build for everyone. And how does that come from reconnecting and building a responsibility to each other are more than human relatives on the planet.

AA: Can we start with history, Cutcha, and have you walk us through a little bit of what happened in Northern California? You just beautifully introduced the people’s connection to the land, so it sounds like they were never displaced as so many indigenous communities were. But then what happened when settler colonialists arrived? When did they arrive and how did they interact with the Hupa and Yurok and Karuk peoples?

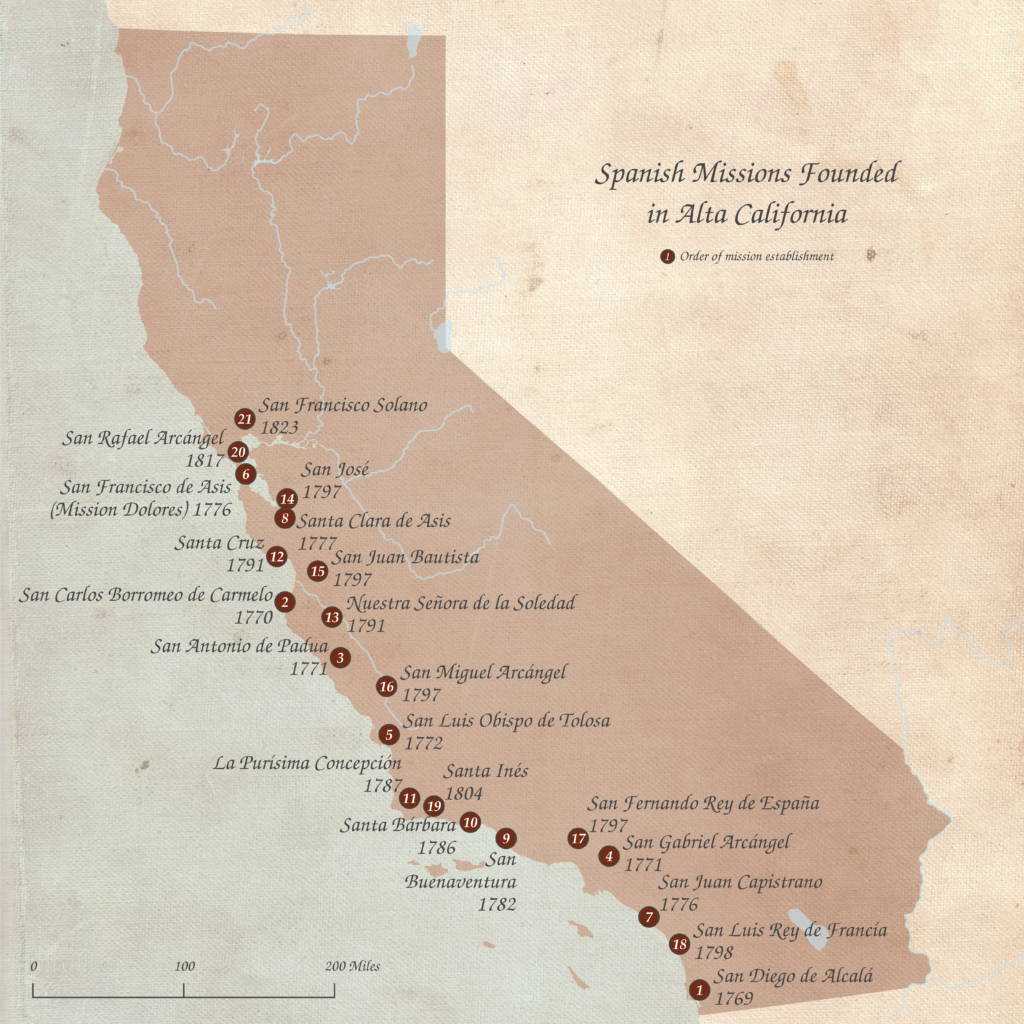

CRB: When we’re talking about what is currently called the state of California, we’re talking about a very large area and there’s a lot of eras of history that take place. What I like to say about California as a state is that we are in an amalgam of history all converging into the same place. Any sort of big era you can talk about in history, something happens here in California. So you’ve got the first invasion by the Spanish, with the Spanish mission system moving all the way through the Mexican rancho system and the change over to Mexico. Then here comes the United States with their interest, and that primarily gets pushed into what becomes the gold rush. You’ve got the post-gold rush assimilation policies. So California as an experience, I think, is sort of demonstrating how settler colonialism converges on an area to try to completely displace and destroy and dismantle a population of people. So everything that happens in California historically is about the genocide, removal, and displacement of California Indians.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, who wrote a great book called An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, says that everything comes down to land. And what really is happening in history is trying to figure out who owns the land, who has the rights to the land, and who gets to keep the land. And everything comes down to that. And in California, they want the land and first and foremost, they want the resources. They’ll do whatever it takes to get it, and they will push whoever they need to out of the way, and they will kill anybody who gets in the way, and that’s California Native people.

everything that happens in California historically is about the genocide, removal, and displacement of California Indians.

There are instances in California history where the United States had been expanding for several hundred years, and when they got to California, the question that people asked, there are actual public records of people saying, “Why can’t we just run them into the ocean? Why can’t we just push them off cliffs?” And there are also instances where people did that, where they were rounding up California Native people, and they would make them do marches, kind of like Trail of Tears but within California. And they would forcibly make them jump off the cliffs into the ocean. And so you’re seeing that the actual goal is to just take everybody out of the situation so that they don’t have to do the same type of work that they had to do in other parts of the country with treaty negotiations and agreements.

So the mission system kind of stops around San Francisco, they build their last mission there. They don’t come into Northern California. So what they say about us up here is that we are relatively late in the colonization cycle, so we are actually able to maintain a number of years where we do have visitors that come to the area. The Spanish come in at a certain point, which is why we have some Spanish names in different parts of the region where we live. The Russians come to trade, but you don’t get the massive influx and attempt to settle the area until the gold rush. And so what we have to deal with is the violence and genocide of the gold rush.

I always try to explain to students in my class that you have to understand California history as being about violence. It takes violence to build what they were trying to build, because they did not want to have to be beholden to indigenous rights. And if you’ve learned about an era of California history where you’re supposed to believe that somehow it was less violent. It was always violence. What Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz says is that no group of people gives up their land, their children, and their futures without violence. So to be told that they just moved forward, or they made this decision, they didn’t want this anymore, there’s always some kind of violent story behind that.

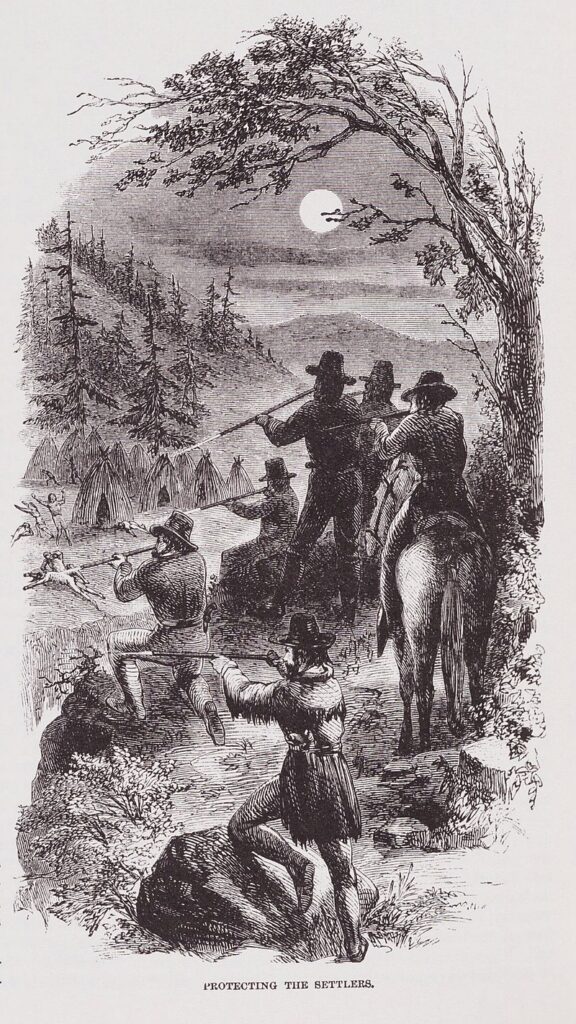

The violence of the gold rush was palpable, I think as a California Native person. I do a lot of work in the archives, so I have to read about and engage with the gold rush. What I often tell people is that these were human beings. I want people to remember that when they read these stories about what it was like to try and maneuver and survive this time. It was an incredibly violent time. It was also sanctioned by the state of California. I can tell you stories about what happened, and just know that none of those people were arrested or tried or put in jail or told that they were doing something wrong. This was sanctioned by the state of California.

California came into existence as a state, and one of the first things it passed in its legislature was the California Volunteer Militia, in which they were trying to hire average citizens to kill California Native people. They passed laws that said that you would get paid per scalp or per head that you turned in. They passed laws that said that you could enslave California Native people through what they called an apprenticeship program. So if a Native person was arrested, they would go before the Justice of the Peace, they were not allowed to testify. They actually passed a law that said Californians cannot testify in court. But then the Justice of the Peace would determine their bail, and if they couldn’t pay it, which they often couldn’t because they weren’t able to get jobs, anybody who was in that space could pay that Native person’s bail, effectively buying them from the Justice of the Peace, and then say that they work for them now as an apprentice because they paid for their bail.

This enslavement system was foundational to how the state of California is built. Indians could be arrested for vagrancy, meaning for standing around. They could be arrested for not owning property, which they legally were not allowed to do. They actually then sanctioned the enslavement of California Native children. What they said was that if you found a Native child with no parents, you could take them to the Justice of the Peace and register them as your apprentice. The easiest way to find an Indian child with no parents is to kill their parents, and people were very open with this. You can see letters that were written from people. There was one soldier who wrote a letter to his commander and he said, I came upon this guy and he had a wagon full of Native kids and he named where they’re from. Some of them are from Hoopa. And he said that he asked him, “What are you doing?” And he said, “I’m going to the Justice of the Peace because they don’t have parents and I want to register them as apprentices.” And then he says that he asked him, “How do you know they don’t have parents?” And he said, “Because we just killed all their parents.” So there was a massive system of child enslavement during this period of time.

When they look at the records, what they determine is that in Humboldt County, for instance, which is where Hupa is from and where I’m from, most of the people who were taken into slavery under this law were children. Most of them were ages 7 to 12, and most of those were girls. And so I often tell people that what they were really trading in was young Native girls. That’s who got the most money paid for them, that was who was the most wanted. When they would take people, they would target young Native girls. And so really what the state of California created was a sex slave industry. They were trading in young Native girls, ages 7 to 12. And they know this, they know that this happened, and you can actually read the records of which families had apprentices and how old they were when they went into the system.

And so to think about that way that you have to exist, and what we talk about in terms of what that meant for us as native peoples, is that while we had been a culture and a society that really centered the egalitarian features of what it meant to have a feminist culture, which meant that women and men and actually all genders were treated equally and that everybody needed to have representation and space and that they were given the ability by which to navigate our society in multiple ways. And women held high political status and high social status. They could choose if they wanted to marry or divorce, they could choose where they wanted to live. These are things that in a settler colonial culture were actually not available at the time and women were actually considered bad people if they tried to vote. And in the indigenous space, they got to vote and they got to represent themselves politically.

And then what happened was that there was a targeting of our indigenous girls and women. So in historical records, what you find is that when they would go to commit a massacre, for instance, they would often kill men outright, and they would often kill elders as well. They considered men a liability, they couldn’t really use them for labor because they could run away. Elders were not used for labor, so they would kill them. They would take the women and children because that’s who was the most wanted within the slavery system. And then they would massacre the babies because nobody wanted to take care of them. And they would do this in the most violent and public way. There are a lot of personal stories about people having to hide and sit through listening to them take babies and swinging them around and smashing them against rocks until they died, or smashing their heads in with axes and hatchets. There’s one story of a child who hid in a tree because she was trying to not get caught, and she watched as they cut the heart out of her little baby sister and threw it onto the side of the road. And she couldn’t cry, she couldn’t scream, she couldn’t make a sound because then they would have caught her. And after they left, she talks about climbing down from the tree and holding her little baby sister in her arms.

I always tell people, I don’t know if I could have survived that. I don’t know if I could have lived through that and come out the other side. But you have these people who did. And they were just like, “We have to do whatever it takes.” And when it came to our women’s ceremonies and practices, and what it meant for our women, we suddenly were like, oh no, we have to protect them and we have to make sure that we’re protecting them from these people. And so there are a lot of really important stories around how we maneuvered that moment. I think things that people don’t understand about that period of time is that when you look at the records, you’ll notice that they registered these young women, 7 to 12, into the system, but they have taken all of the women. So what happened to the adult women? What happened to teenage women? Generally, they were put into a concubinage or into prostitution, so they didn’t have to be registered. And so they just disappeared into this system and were sold to people.

And so we recognize as California Native peoples that there was a period of time where it was really dangerous for us to have a women’s ceremony, to celebrate women, to have women in upper leadership positions because those are the women who would be targeted. And so what you start to see is our foundational way that we approach what it means to have a culture that really values all genders. We change that positionality. We change how we approach things. Some people will tell the story that we learned or we adapted and we became more advanced, but it really was the threat to our people.

I think the most important thing, though, that I always tell people about this period of time, this attempted genocide of us, is that we were human beings navigating that. And through that, we demonstrated a type of strength, an ability to think about our future. I often think about it because I could not imagine having enough strength to do what they did. And what I demonstrate for people is that there was all this time where people were trying to stop everything about who we are and kill us at every chance that they got. We could walk outside and be shot, we could be taken up off the street and never return. And yet we’ve made these decisions to pass on these stories. I have to remember these things. I have to carry this forward. Because someday we’re going to need this record, this document, this story, this thing. And they were always thinking, “What are we going to do for this future? How are we going to heal this land, this space?” They were like, “Five hundred years from now, how do we come back from this?”

There’s a really beautiful story about Hupa in particular. Hupa as a group of people, we live in our valley and our valley is the center of the world. I love that about Hupa. We’re like, you don’t know where the center of the world is? It’s in Hoopa. And we came into being there. During the gold rush period of time, we negotiated a treaty to keep this area. And what happened in California, which is a really awful situation, is they decided not to ratify the treaties because everyday citizens and the people in the legislature thought the California Indians were getting too much land. Why don’t we just kill them all? Why do we have to negotiate and give them land? They pushed back and Congress decided not to ratify the treaties. They didn’t tell California Natives that that happened. They put them under an injunction of secrecy and pretended like nothing happened. So tribes were left in the position of having to renegotiate for what their land spaces were going to be.

And it was just complete chaos for most people. In the case of Hupa, we fought a five year long war against the federal government. And for three years it was just consistent war. Making that decision was really difficult for us. We are not a tribe that did war in that we would go and like war with people and kill them. That was not our value at all. To make a decision that we needed war to keep our area, because we knew that’s a threat to the government, that they would consider violence. But we held our position, which is we needed to keep the valley. We needed the valley. At the heart of everything, we wanted our valley. And we held them off for three years until they came back to the table and said, “What do you want?” And we said we want our valley. We want our place that we came into being for all time. And then we got an executive order from the president at the time, who was General Grant, who said, okay, we will sign this executive order, and you will be able to keep your land.

And I think that that moment demonstrates that Native peoples were experiencing genocide, but they’re still politically navigating what’s happening around them. They are still operating as nations, and they are still thinking about the long-term connections to land and space. So for anybody to think they gave it up, or they walked away, or it was easy for the taking. No, it was constant political negotiation, discussion, pushback. There were all these things that native peoples did. And then the response to that was often the threat of massacre and the idea that a whole group of people would rise up to still try to get rid of us and that there were no legal repercussions for that. We couldn’t sue them. We couldn’t take them before the justice of the peace. And so when we talk about stolen land, what we’re talking about is that it’s not just that the land was stolen, it’s that what it took to get that land into the possession of the peoples that have it today, it was a genocide. It was an attempted destruction. It was killing and murdering human beings. It was people.

So I talk about this in the context of what it means now to live in this land. And I think about two things. One, I always tell people that I have a daughter and I always say that there was a period of time in California history where they could have shown up to my house at any time that they wanted to, and they could have taken my daughter from me. Or we could have been at a ceremony and they would have shown up and they would have torn her from my arms. And I don’t know what I would have done. What would I have done? How do you navigate that as a person? And I want people to think about it. If I give you the statistics and I say there were this many massacres and there were this many people put into slavery during the 1800s, that’s one thing. But to think about what you would do when they tear your daughter away from you and she’s screaming and crying and you don’t know how to stop it. How do you navigate that moment?

And then what does it mean that even after that, California Natives were still fighting. They were writing letters, they were holding protests, they were demanding people show up and tell them where their kids are. They never stopped. They never gave up. They were just like, “I want my daughter back.” And what you will see is letters that are written where they’re writing to the heads of the forts, and the president himself, and the governor, and they’re like, “My daughter was taken from me, I want her back.” And to remember that we were people, I don’t know what I would have done. I swear, every day I tell people, I don’t know what I would have done if they had tried to take her from me. I can’t even imagine it. But I know that that strength carries through me.

In the case of Tuluwat, which is an island in Northern California that they recently returned, actually, to the Wiyot peoples a couple years ago, the city of Eureka made a decision to return Tuluwat, which is a sacred space for Wiyot peoples. It’s a place of world renewal for them. It’s the center of their world. And it was taken because of a massacre that occurred there in the 1800s. And this was one of the largest massacres in our region. It was committed against Wiyot peoples when they were in a world renewal ceremony. People showed up in the middle of the night to the island. The island happened to have primarily women, children, and elders there because the men would stay in a different place when they were in ceremony. They showed up in the middle of the night. They used what they called “quiet weapons”. This would be like no guns. They didn’t want anybody to know what was happening, so it was mostly hatchets and knives. I often tell people, think about what that means, what was really happening to these people as they’re awoken in the middle of the night to people mass murdering them. And that kind of killing is– people can beg for their lives. People can cry and beg and plead for their lives. Because there’s enough time where you’re having to watch that happen. They also talk about how people were running and they would get stuck in the mud, because the island is very muddy at certain times, so they couldn’t actually move.

There were two survivors of that massacre. One was a baby and the other was a woman. What they know about her is that she was stuck in the mud, that she was surrounded by the murdered peoples of her tribe that she had grown up with. The sun rose that day and they came to see what had happened and they found her stuck in the mud and she was singing. And I just think about what that took. She was singing a song and the tribal elder who talks about this, what she says is that she thinks she was singing a mourning song because what she said was, here’s this woman who has watched and experienced this horrific thing. And she looks around and says, “I have to sing my people to the next world.” And the fact that we’re having this conversation now, that I’m sitting here as someone with a PhD, if you would have told anyone during that period of time, “Don’t worry they’ll be telling this story,” I think you would have had a lot of people saying that that would be impossible. But we knew it was possible. It’s the reason why we kept telling the stories to move forward.

AA: Did you grow up knowing those stories, Cutcha? Was that kind of passed along to you from your ancestors from your, you know, your grandparents and your parents? Or were a lot of these learned as you started researching for your book?

CRB: No, it’s really something that we grew up with. If we’re fortunate enough to have family members that are constantly telling these kinds of stories, we grew up with it. I remember driving around with my mom and we would drive over the bridge in Humboldt and she would point and she would say, that’s Tuluwat. That’s a place called Renewal. She would say, they tried to massacre people there. You have to know that. What she would say and what my great-grandfather would always say are things that the history is written on the landscape. The land knows what happened. It had to experience that kind of destruction. So we see it everywhere. Everywhere around you is this genocidal, settler colonial history that is attempting to destroy. And it’s not just destroying the peoples, it’s destroying the land, the more than human relatives, like the birds and the bears. All these things that we’re seeing now are a result of an attempted genocide of California native peoples. So the land itself is scarred and needs to be able to heal.

And that starts with telling the story of understanding what happened. I think most of us grew up hearing from people about what happened in the gold rush. I think it’s important. I’ve done work with my own daughter, but I also do work in curriculum development and interventions. And what I’ll say to people quite often is that what we know from the statistics and the reports is that native children are the least likely to graduate from high school and they’re the least likely to go into higher education. They struggle the most with high rates of suspension and referrals and they get pushed into this sort of system. And then what you see is that they’re not succeeding. And we know that. And then I say, now let’s look at what we do to them in the curriculum. We teach them a curriculum that disempowers the story of what it means to have moved through this, because we take out any of the violence or discussion about what it means to live in this system today. And then we teach this sort of sanitized history and we disempower Native youth through those stories. And how can they be successful in that when they are able to learn these truths?

And I think this is for all children, but also Native kids, they suddenly recognize. Why it is that they walk around and feel a sense of this world very differently and what it is that they’re experiencing. My own daughter, when she did her California mission project, the California mission project itself is really sanitizing the mission system, also an enslavement system, also an attempted genocide. She had to do a mission project and we agreed that she would do the San Diego mission. And what she did is she built it and then originally, I said we can build it and then we’re going to set it on fire. And we’re going to turn in the ashes of this mission. Because the Kumeyaay, who are the people of San Diego, led a revolt against the mission where they set it on fire and burned it to the ground. So I was like, it’s historically accurate. Turn in like the charred remnants of this mission. Her teacher was like, we can’t just have charred remnants. So she actually built the San Diego mission and then put flames going up the side of it and made it look like it was on fire and had native people running in. And she then used her whole essay about it to talk about the Kumeyaay revolt, but never from a perspective of what happened and then it was done. She was talking about what it means for the Kumeyaay today. That they survived this mission system, that now they’re revitalizing their languages, their cultures, that now they’re really invested in their community practices. She talked about how this informs our current experience, and that’s what you need to know when you’re learning about the mission system.

And it was a really powerful moment for her. I actually asked her, “Does it make you feel bad?” She had to learn these things that happened in the mission system because she wrote about it in her report. And she was only in the fourth grade, right? And I was like, “Does it make you feel bad? You had to learn about some of the horrific things that happened to the people in this mission.” And she said, “No, Mom, it made me feel like California Indians are really powerful and they’re really important. And they’re a significant part of this history. It made me feel like we are important people.” And I was like, well, that is why I think this is so important. So I always tell people that we grow up knowing it. So when you’re saying “I don’t know if we can teach this kind of history to kids,” we grew up knowing it. So really, who are we protecting when we’re saying we can’t teach it in school?

AA: Yeah. The white kids, and they need to know it. They really need to know it. They cannot be like I was, 40 years old, before someone ever says to them, “You realize you live on stolen land, right?” People need to know that from the time they’re kids. Well, Cutcha, let’s shift gears just a little bit and talk about the title and the subject of the book, We Are Dancing For You: Native Feminisms and the Revitalization of Women’s Coming of Age Ceremonies. So can we go to what these coming of age ceremonies were originally, and then the process of revitalizing them?

…who are we protecting when we’re saying we can’t teach it in school?

CRB: Yeah, I think what’s interesting about coming of age ceremonies for native peoples in general is that they’ve always been really important to the cultural, societal makeup of who native peoples are. There’s not a lot that ethnographers and anthropologists that do this kind of cross-cultural work are willing to say is universal to Native Americans in general, because we’re so diverse from each other. There are over 500 different tribes federally recognized in the United States. But what they will say is that every tribe in North America had some kind of women’s coming of age ceremony that was in particular done around a woman’s first menstruation. And so they say this is something that they viewed and valued as particularly significant to a healthy society, is being able to demonstrate the importance of the role of women within their culture.

I found that very significant because really it’s around menstruation. So a lot of times people will ask me questions like, what about people who don’t identify as women but menstruate? So, people who menstruate. And I say, I mean, we are talking about inequality across genders. And so, if you’re saying you’re a person who menstruates, then you also would have had some kind of coming of age ceremony, because it really is something important that we identify as what’s happening in your life and your body and your experience. And I think it was really cool. I always say to people, I feel like native peoples were the first developmental psychologists. We were looking at this situation and we were going, you know what is difficult? Adolescence. And you know what is really hard to navigate through? That moment when your body and life is changing. You know, we should do? Something to actually help.

So we have this entire ceremony that’s really set up to empower a young person as they’re moving through adolescence and as they’re understanding what’s happening specifically around menstruation and menstrual practices. I think also, both historically and contemporary-wise, it’s a community based ceremony. It’s a way to help a young person to understand that they have a support system, that they’re not alone, that they’re a key part of their community, that they’re going to come into different roles and that that’s okay, that they have the tools they need to navigate that. It empowers them to start thinking about how they make decisions in their own lives. It asks them to make decisions, but in a way that they’re very supported the entire time.

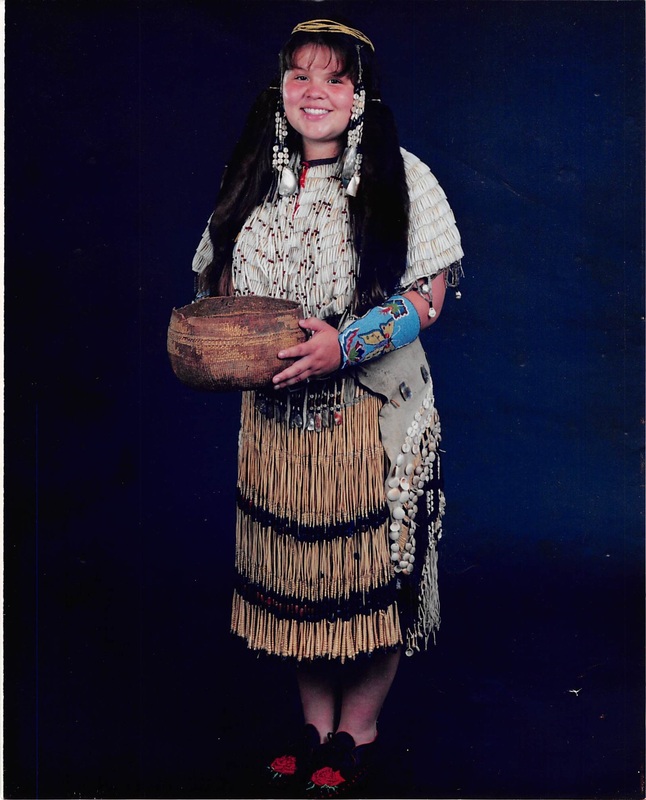

I also think it’s a really key ceremony for helping people to connect across families and cultures. Because oftentimes a young person could be coming from two different tribes. Their parents got married, but now everybody’s coming together. So politically it creates good political will amongst people. They’re able to know each other better. It creates connections to land which help you to understand your responsibility to the land and place that you come from, and how you are integral to whether or not the water is clean enough that you can actually use it. You’re integral to understanding your connection to all of the more than human relatives that are part of this ceremony through your regalia, the things that you’re wearing. It connects you to all of those things. And I feel like it does that still to this day.

There was a period of time where we didn’t do these dances publicly. One thing that they’ll say about Hupa in the literature is that we were very public about our women’s ceremonies. In fact, we’re one of the tribes that they identify as being some of the most public people. We had big celebrations. And then what you see in colonization is that patriarchy is at the heart of what needs to happen for settler colonialism to actually work. They need a patriarchal foundation to that. And not just that, they need a heteropatriarchal foundation. So they come in and they see that our society is what a lot of people are talking about now, we’re a very queer society to them because we have representation of all different kinds of genders, all different kinds of roles, all different kinds of ways people love and live with each other. And they are just like, this is unacceptable. So they decide that they have to change that about us. And that particularly becomes to them about targeting women and queer individuals for either assimilation or eradication. And so when that happens, we know that they’re targeting our women’s ceremonies in particular. There are stories in California especially about them making decisions that if we’re performing a women’s ceremony, they would show up to that ceremony. They would take that girl in particular to rape her. And they would be like, “This is because 1) you guys are doing something wrong by celebrating her, and 2) you’re advertising her as a woman now, and this is what we can do.” So at a point doing that is dangerous.

We also had a lot of menstrual customs and practices that really were about empowering women. And one of the things I do in the book, there’s a chapter where I’m specifically talking about why we believe certain things about indigenous peoples and menstruation. And that all comes from anthropology making this decision that somehow we’re supposed to be primitive and backward. But really in reality, our practices and customs around menstruation were about the power that comes from menstruation and the fact that it actually elevates your status and it makes you a really important part of a culture and society. And how are you going to navigate and maneuver this period of time, which deserves the respect of concentrated meditation and engagement, and deserves the respect of what you bring to your culture and society because of what you’re able to experience during this period of time.

And so we have these practices where women would go into what we call the minch, or the women’s house, and during their menstruation this was the time for them to be in concentrated meditation. And what that meant is that their family was taking care of them, bringing them food and drinks and doing their hair and helping them feel really comfortable. And they would engage in a lot of really important conversations. I’ve actually had people tell me that they felt like it was almost like a think tank, because you have a bunch of women in the space together and they would just talk about what the world should look like. What should we do? Because they had time to really concentrate during this period of time and they’re being taken care of. Then they could come out and say what their ideas were.

It also was considered one of the most powerful places in the village because menstruation is tied to an uptick in power and ability. So women, after they gave birth, would be in there with their newborn babies because that’s the most powerful and safest place that you can be during this period of time. Women who had miscarriages or were having particular issues would go in there because that’s the most powerful place that you can be. And that will be the place where people can heal you and help you. There are stories about medicine women. In our cultures, especially in Northern California, it’s primarily women who are the doctors. They’re the medicine people. And there are multiple different kinds of doctors. And this is one reason why you can demonstrate that we had a really important status in our culture and society. But there are stories about medicine women who are doing work to try to help somebody with whatever is ailing them, and then they feel like it’s not working and they’ll say, “Bring me the menstruating women because they are the most powerful women and they can help me to fix this situation that I’m in.”

And this is really important because we stopped doing a lot of those types of practices especially during the gold rush. And the story that gets told is because we figure out that it’s uncivilized or it’s backward to do that. But in reality, it’s because it’s completely dangerous to send a woman to a woman’s house, to have a house filled with women, when you’re talking about them being taken and put into these situations, right? Because of the gold rush and the ongoing massacres and genocide. And then what happens is it becomes dangerous to talk about it. And so when the ethnographers come in after the gold rush period, and they start asking all these questions about our women’s practices, a lot of people would say no, we don’t do that. Or we don’t have that. Or they sort of push it aside or they pretend like it’s not going on because they don’t know what it’s going to be used for. They don’t know what’s going to happen. And one thing that gets pointed out a lot in the records is that even though there are all these people writing about practicing these menstrual customs, nobody had actually ever seen one because they were not invited. We were still doing them, they were not invited. But also, by the time they get there, you’re talking about being after this genocidal period of time.

What that means for us today is that we’re revitalizing. We’re building a resurgence. Our current ceremonial practice is around bringing this dance back. We started that process over 20 years ago, having this discussion. I think elders have always been talking about the women’s ceremony because in Hupa we had three primary ceremonies that we do that are called the “high dances”, the dances that are done for all time in the world beyond. And two of those are rigorously researched and studied because we maintained those even through all of the genocide. So that’s the white deerskin dance and the jump dance. That’s what they’re called in English. We’ve done those consistently the way we’re supposed to, and to keep the world in balance, to keep the world healthy. It’s why a lot of ethnographers and anthropologists have written about them, because during the 1900s, they’re like, “Oh, they’re still doing this dance, this is obviously very important.”

But we weren’t doing the third dance that is done for all time, and that is the flower dance, or the women’s coming of age ceremony, called the xoq’it-ch’iswa:l. And when they came to look at what we were doing, they would say, “Oh, you guys are a very male-focused culture” because the two dances that we were doing primarily feature men dancing and singing. It does not mean that women are not integral and key to doing those ceremonies, but when you’re talking about who’s doing the dancing and singing, that’s primarily men. So they were like, “this is a male-focused, patriarchal culture.” But they’re missing that our third dance that you had to do in order to keep the world in balance, according to our first people, our K’ixinay, is the women’s coming of age ceremony. And they’re missing that the reason why we weren’t doing that at the time was because of this violence and genocide.

So when we decided to bring it back, we were looking at all these records and stories to try to build something that recreates this ceremony for us today. It took a lot of years. It took a lot of reading and outreach. But what I will also say, that is pointed out in the book, our medicine woman talks about how all we had to do was scratch the surface. All we had to do was say we want this dance back and then things just started happening for us because she said it wants to be again. It wanted to come back to us. We truly know that it exists and it says “okay, they want me now.” And part of the ceremonial practice is calling the dance down to us. Part of the ceremonial practice is that the girl herself has to sing a song to the other world and say, “Can you send this dance to me?” And then what we say is they stop and they point their sticks in our direction. Sometimes we say they even come to that dance because they’re giving us the dance. Because they’re doing it right now. They’re doing it for all time, all three of those dances. And we call it down to us when we need it here.

And what she said is that the minute we called it, the minute we were like, “let’s do it now,” things just started coming to us. People remembered things they didn’t know that they remembered. Elders had dreams and they would then call people up and be like, “I forgot! I forgot that when I was a kid, I went and did this thing and my grandma told me this.” We started to find things in people’s houses they didn’t even know were there, papers or things people had written, things people had jotted down. A bunch of information kept coming to us. Again, because our medicine woman was like, “Because we called it to us.” That’s all we had to do. All we had to do was say, “Can we have it please?” And they were like, “Oh, you want it? Here’s everything.” And now we’ve been able to take all of that information and build a ceremonial practice that I think is not just empowering for our young people, but also for all the generations that didn’t get to have a ceremony, that weren’t quite doing it yet. I think it’s also powerful for our elders because I think this is what they envisioned. They never stopped talking about it. They never stopped bringing it up. They never stopped trying to get us to do it. And now we’re doing it. And I think for them, seeing something like that come into being is really demonstrative of the fact that we can do this. We can change the world if we want to. I feel like with this revitalized ceremony, we have changed the world. So if we can do that, then it has to help us to believe that we can do that and all the things that we need to do.

AA: That’s amazing. I was going to ask you, one of the things that stuck out to me was that you talk about the first generation that was doing the ceremony after a long time of not having it been done. That they were a little more hesitant and nervous probably because they had absorbed some of the colonizing culture of embarrassment around menstruation, like, “I don’t know if I want to do this so publicly.” But that really soon, like within a few years, the next generation of young girls were requesting it and saying “I want a flower dance when it’s my turn.” Can you talk about that? And also from the point of view of the girl, what does she do during the flower dance and what does the community do? What does it look like for her?

CRB: I think the important thing that I always tell people is that it took ten years to completely intervene in the patriarchy that had been internalized by the first generation. I think it’s a primary concern about the public declaration of menstruation. But there was also the internalization of a patriarchal culture that tells you that as a woman, you’re not supposed to be at the center. You’re not supposed to be out there. You’re not supposed to be creating yourself as a leader, that there’s some other role that you’re supposed to take. So pushing back against all of that. And then pushing back against this idea that somehow we were going to do something weird because nobody had really seen it. And so they were like, well, what’s going to happen? And this idea that you’ve internalized that somehow what indigenous peoples do is weird or odd or not what you would want to do. But it took only ten years. And after that ten years, you had the first girl who was like, “I want this. This is what I want. And I’m going to do whatever it takes to get it. And I’m going to put all the stuff together.” And I think what was really beautiful about that change is what you saw. They really talked about how they had seen these girls who had done it and who had taken that opportunity and who had pushed themselves even with the hesitation. And then they’ve seen who they’ve become and they want that.

And so then they start really pushing themselves. And I can tell so many stories now about young girls who were coming from situations where their parents couldn’t help them in their situation. We had a couple of foster youth who are like, “I don’t really have a parental family situation that can actually help me put this dance together, but I’m going to do it.” And they would come to our medicine people and they would say, “This is what I want to do. And I’ve started this process.” There was one girl whose parents were going through a really difficult time and she wanted to have a ceremony. And I also know that they’re in their own situation, so she went fishing one day and caught a big fish and she walked up the hill to my parents’ house and they were like, “What are you doing here?” And she said, “I brought you a fish. I want to hire you. I want you to do my dance.” And that moment was really important because it was them seeing that they could also step into that function. I think it’s really interesting now because I wrote the book while we were going through this process. I kept telling people that my goal was to document it from our perspective because I didn’t want anybody else to be the voice to write about this. Because this is the work we did. And for far too long, we’ve had our ceremonies written about by other people. And it was our turn to tell this story, and we needed to make sure the story was ours.

But I did it through graduate school and after graduate school and then worked on the book for a couple of years. And I had always been in multiple roles. I’ve been the role of an auntie, a community member, a supporter. It was just this last year that I got to be a mom because of my daughter. And it was really interesting because I always used my daughter as an example. What I realized about her is that she’s never known a time when we didn’t do this. She was born after we had already been doing it for a number of years. So in her mind, this is just what we do. It’s not a question of the time when we didn’t do it versus now, which a lot of us carry forward. But instead this is just who we are and Hupa people celebrate young women when they start menstruating. Hupa people do these kinds of dances. She’s been planning her dress, she’s been planning her people, she’s been talking to people about her dance since she was born. And this is where I see how quickly you can push back against settler colonialism, which acts like the longest period of time is when we didn’t do it. But actually, to the world of our next generation, the longest period of time is that we only do it. That’s what we do. And I think that’s so beautiful how quickly this can become their world. And we sort of hold on to this idea that settler colonialism is forever, that it’s always going to be there. But how quickly for this group, they just said no, that’s just what we do, and this is who we are, and this is what’s important.

this is just who we are and Hupa people celebrate young women when they start menstruating.

And so she got to do her ceremony this past summer. And it was a real eye-opening experience in terms of understanding developmentally what it’s like to be a mom versus a community member or an auntie. I always tell people that you learn something new every time you think about and do ceremony, that’s what ceremony is supposed to be for. There’s not a standard thing I can tell you that every girl does because it’s dependent on what she needs. There are some aspects of it that we try to have them each do, but they do it in their own way. And she spends a lot of her time during the day doing multiple things that will help her to demonstrate to herself that she has the strength and fortitude to be able to navigate life. She does a long run each day. It gets longer each day that she’s in ceremony. Running, for some reason, is universal to most of the coming of age ceremonies in Native cultures. We saw the value of running and connecting both to land and yourself in multiple aspects of women’s ceremonies. In our ceremony, what we say is that how she runs is how she will live her life. And so the path is representative of the life that she’s going to live. And we want to demonstrate to her that she can do it and she can make her own decisions. So she can run as fast or as slow as she wants to. If she stumbles, she’s supposed to go back and do that same part of the path again to demonstrate that sometimes you’re going to stumble and then you’ve got to go back and try again. If she falls down, she has to pick herself up. She’s running to sacred bathing spots that we have along the river. If she wants to stop there for a while, she can. If she wants to do it for a short time, she can. We’re trying to demonstrate for her that she can do this and she’s going to be fine. This is the life that she’s going to lead and you can do it.

As a mom, it was really interesting to experience that my job was to show up and hand her over to her medicine person and her grandma. And then her aunties would come around her, but I didn’t really see her for three days of the ceremony. She was in ceremony for ten days. She was in isolation from me for ten days. And then the public part of the ceremony is three, five, or seven days, depending. But I didn’t really see her a lot. And I always tell people that when she was a kid one time she had to go on this sleepaway camp and I woke up at night and I woke up my husband and I was like, “What if she’s cold? What happens?” And he goes, “I don’t know, just put on a jacket.” I said, “We should call her and make sure she’s not cold, but they took her cell phone. So who do I call? Because I’m going to check in and make sure.” And he was just like, “No, I’m sure she’ll figure it out.” And then she came home and I was like, “So how’d it go?” And she was like, “Oh, it was fine. But one day I went to go to the bathroom. I got kind of lost in the night when I came back, but then I figured it out.” And I was just like, “You got lost?!” I was freaking out about this. And I always tell people there’s something really important about that moment of giving her over and then having to just experience as she makes these decisions on her own. I think that’s important for her that she doesn’t need me to make those decisions for her. I think it’s important for me to be able to say, “You can do it, you’re going to be okay.” All those things I see now that I didn’t. I’m thinking about those interconnections.

I think that a lot of what she does is she connects with other community members. We select for her a group of women that we know will be there for her for the rest of her life. Generally close friends, aunties, people who are sort of representative of people she can turn to. Because sometimes you don’t want to just talk to your mother or father, you need to have community. So they come and do talking circles with her, they do exercises, they do discussions, they teach her something so that she can see that she has a community around her. What my mom says, my mom is a medicine person, she says, “What does it mean when a community will stop the world for you? What does it mean for you as a young person to see that a community will stop the world for you? They will show up, they will be there each day, they will stay all night on the last night and sing for you. What does that mean for you?”

So when you start to think, “Do I matter in the world?” You can’t ever go out in the world and think you don’t matter. A whole community did everything they could to tell you, “You are important to us. And this is why we’re here for you.” So if you come to see the actual ceremony, what you’ll see is us dancing and singing at night, and she’s in the corner of the house and she has a blanket over her. She’s in a sort of concentrated meditation. She needs to be under this space so that she’s not paying attention to everything around her. It’s supposed to help her to demonstrate to herself that she can do this. She can have control over her own emotions and feelings. We’re there singing songs, we’re laughing, we’re sharing stories. Her job is to try to not laugh. I think this is great about us. We say that it’s another way of her demonstrating her own control. But we say if she laughs, she’s going to get wrinkles later.

But we tell jokes all day, we tell jokes all night. I would say we’re hilarious at four o’clock in the morning. I have no filter at that point. We’re trying to make her laugh. And what I love about interviewing some of the girls is that we were talking about this and I was like, “Well, what was that like?” And they said, “Well, sometimes it was really funny, so I laughed. But what I thought was, ‘I’m going to be a really happy, wrinkly old woman.’”

AA: I love that.

CRB: So joy is a huge part of this. We try to make it a really supportive and joyful space. What our medicine woman talks about sometimes is that the world doesn’t create joy for our indigenous youth. Moments of just feeling joy about being an Indigenous person. And we are creating joy in a world of trauma. And we’re pushing back against trauma through joy. And what does that mean as Indigenous peoples, that we value laughter and joy, in particular, of what you need to build. Because that part of the ceremony is not something we added in. It was very clear and the ways that we got instructions from our first people that we have to bring in laughter and fun and joy. This is very important. It actually is key to most of our ceremonies. We should have a time in most of our ceremonies when you’re supposed to try to make somebody laugh. It’s really interesting how important humor was to us and still is to us.

Also what you might see is that on the last day, she comes out, she’s been in ceremony, and she does a final run. She comes out in a full regalia dress that she’s usually made or that is part of her family, and then we’re able to receive blessings from her because we say that this is the time in her life when she is one of the most powerful beings that we can have in our space. All that we did for her, she’s brought into herself, and so she will take and receive blessings from us. We often give her gifts to welcome her into the world, to help her to build a foundation, because what we said is that we never wanted anybody to feel like they didn’t have enough and that they had to make compromises in their life. So we bring gifts, we bring things that she’s going to need, and then we accept blessings. And then we eat, because eating is a huge part of who we are as indigenous peoples. You have to feed people. You have to make sure that they’re eating well. And so we have a big feast.

I will say that my daughter, when I watched her come out in that moment, it was really interesting to see as a mom this young woman emerge from this space. And I remember I had to sing the final song in her ceremony with the medicine person. And I was like, “I don’t know if I’m going to be able to do this.” And then she said, “Okay, but just don’t look at her. If you look at her, you’re going to start crying. So don’t look at her.” So the whole time I’m looking down, trying to sing this song, and I would sneak these peeks. And she was confident. Confident in a world where most 14 year old girls get to be confident. And she was confident in herself and what she was doing there, and that has been carried forward in all the girls that I’ve talked to. This idea that I can take up space and I can be confident. I can be the person that leads.

And a lot of the time, people will say how important that has been for the men and the young men in our community, how important that has been to actually dismantle patriarchy. Because what she says is that when you sing and dance over a girl, you can’t think of her as an object anymore. You cannot objectify her. You have done something really important and ceremonial and sacred with her. So now she’s not an object, she’s a person. And not only is she a person, but she’s a sacred person to you. And so this is how we’re dismantling a patriarchal belief that somehow women are objects or less than. Because you can’t. You just can’t. Because you have seen her at her most powerful, you have seen her come into herself and into being. How do you then ever take that away from how you view her in the future?

And I think it’s really a powerful push against patriarchy that says that women aren’t supposed to take on roles like that. And I noticed it in my own father. When I was 12, I started menstruation and I had to call my dad, and he didn’t know how to respond to that. I remember he was like, “Okay.” He just didn’t know what to do. And I was like, “Yeah, I didn’t want to call you either, Dad, but mom made me.” Yet, now my dad is in his 70s and young girls will show up to his house with my mom, and they’ll sit down, and he’ll say, “What are you doing here?” And they’ll say, “I started my period. I started menstruating.” And he’ll go, “Congratulations! You get to have a flower dance. That’s so exciting. You should feel really proud of yourself.” And they’ll have conversations. It’s his first response. It’s his first instinct to this moment. And I think even those moments are really showing that the work that we’re doing to physically enable our older generations, our current generations, our future generations to demonstrate that we can dismantle patriarchy, we can build a world without it and how important that’s going to be to these young people growing up and being like, “I don’t accept patriarchy as something that is supposed to exist. I know what the world looks like, feels like, and functions without it.”

AA: Wow, that’s so powerful. And that was actually the next question I was going to ask you, and you already answered it. I was really surprised as I was reading about the flower dance, at the point that it did become apparent to me that the whole community is there. The brothers are trying to make her laugh and there are grandfathers. And it moved on to that section that you just spoke about, about teenage boys, and it totally de-stigmatizes menstruation. The whole community can be excited about it. And I just am so inspired. It’s really, really stunning. I’m so, so grateful but sad that we have to wrap up our conversation, Cutcha, because this has been so fascinating and instructive. I really want to thank you from the bottom of my heart. Is there anything that you’d like to leave us with as we wrap up the episode?

CRB: Yeah, now that I’ve experienced it as a mom, sometimes people will ask me if it changed my understanding of what was happening in space. And I think it extended this idea that I think everybody that’s doing this ceremony, you’re always doing it at different parts in your life. And I think you get out of the things that you’re doing what you need to get at that moment. So that’s the beautiful thing about how you teach through ceremony, because you’re never going to get the same thing twice. And the girls tell me that what they’ve learned and the moment that they take with them, they constantly go back to their flower dance and their family as a moment to refer to when they have questions like “what am I supposed to do now?” And even some of the girls I’ve interviewed, because research projects and things take a while, they’re having their own children. There are actually a number of them that had children this year. And they constantly go back to, “I know I can do this. I know I can get through this because I got through this thing when I was 12, 13, 14 years old.” And they talk about how those lessons carry through their entire life. They also talk about how it carried them through being able to feel successful in college. One of the girls talked to me about how she said the first time everybody had to pull an all-nighter, everybody was freaking out. Like, “how am I going to stay up all night and write this paper?” And she said, “I said to myself, ‘I’ve stayed up all night after having fasted all day and then did a mile-long run. And then I sat under the blanket next to a fire and I was fine. So I can do this.’” So the way in which it constantly helps to inform a foundation of them moving through all stages of their life. It’s not just that moment, but there is something about the intervention at that moment.

And I think it’s important for people to understand that what the studies say, and this is sort of across the board, is that a girl’s self esteem plummets during adolescence, while a boy’s will increase or stay the same. So we know that whatever we’re doing in this contemporary culture that we live in, is plummeting girls’ self-esteem. And then what you’re seeing in girls is that the onset of suicidal ideation is 11-13, and the onset of substance abuse-seeking behaviors is 11-13. So what we’re doing to them at this moment is causing this massive spiral of why we have the situations that we have with a number of our young people, and especially our young women.

And this particular ceremony intervenes at that moment. And it’s that you’re important, you have these tools, we are centering you here and we’re going to help you through this time. And I think that’s so important, intervening at that moment, building that foundation. What I’ve seen now, because we have fifteen, twenty years of these girls now who are doing this work, is that that foundation is important. And they have drawn from that multiple times. And so with my own daughter, when I was watching her build this foundation, people said, “Well, what did you learn?” And I said, “You know what I learned this time?” Because I learn something new every time. “What I learned this time is that I needed to figure out how to become the mother that she needed, and not the mother that I expected myself to be or the mother that anybody else expected.” So being able to pause and be like, “I have to figure out how to be her mom through this period of time.” I think it changed and adapted how we approach each other, our relationship.

I’ve stayed up all night after having fasted all day and then did a mile-long run. And then I sat under the blanket next to a fire and I was fine. So I can do this.

I also think there’s something very insightful about the Kehenai, our first people being like, “At this time you need a break from your mom. You’re a teenage girl.” And I feel like that’s a very insightful thing, because I think that that is totally true. And we got to reconfigure how we see each other. And I feel like mending and healing and building those foundational relationships again, at adolescence, I think we’re going to see that that’s a praxis that should be universalized. And I am constantly learning as we’re doing this ceremony. I’ll probably have new insights when I’m the grandma and I’ll have new insights as I’m continuing to see how this builds in our community.

AA: Oh, I also was thinking this should be universalized as well. And just for listeners again, I highly recommend the book. I would say this is something that can inspire us to come up with a ceremony that we want to do in our own family. Of course, not appropriating someone else’s culture, not appropriating someone else’s religion or practice, but think what would make sense that’s authentic to me or to my family history that goes back to my ancestors or something new that I want to do. But I totally agree to celebrate girls. And boy, the image that comes to mind from you speaking now, that didn’t stand out to me as much when I read the book, is of the girl on the run deciding for herself how fast to go, where to go, when to pause, when to go faster. And I thought that any ritual that I have undergone, different rites of passage in my life, have been all directed by men and very heavily prescribed. First do this, now do this. And even with the love that has been there for me, the messages have been like, “Don’t question, this is the way you need to do it.” And just the completely different message to give to a 12 year old girl to say, “You’re completely capable of doing this super hard thing all by yourself. We’re here to support you, but you decide. You can do it.” And just the confidence that that would give you. Anyway, I would love to see every young girl get that in their family and in their community.

CRB: Our medicine woman, when she talks to the girls, they’re like, “Well, what if I am really slow?” She says, “We’ll wait for you. Don’t concern yourself with everybody else, we’ll wait for you. That’s what we’re going to do.” And then they’re like, “Well, what if I take a lot–” She says, “We will wait for you.” That’s not something we’re going to say, like we’re walking away. But people also ask me a lot, “What about the things we can do for other girls?” And I always say that there have been a lot of studies that show that girls walk out of this period of time just completely devastated by what happens to them in adolescence. But also the messaging that they get. The studies also show that the simplest thing you can do that actually combats this is to have an open, frank, and honest conversation with them about your experiences, especially positive experiences around menstruation and adolescence, to open them up to the fact that it’s a shared experience people have. To have that moment to stop and actually have that moment with them. I was like, I wish it was super complicated in terms of what they say actually works. It’s not. It’s just to create a space to talk to celebrate and build a camaraderie around these moments. And I think even something like that is just a start.

Now, what I always tell people is that I don’t think any 12 or 13 year old girl I’ve ever met acts like they’re super excited to do that part. But you do it anyway. It’s like what we learned about this ceremony. You do it anyway. They have a lot of questions and hesitancy perhaps, but what you’re building is the foundation. And that can be a number of things for people. And that’s what I encourage people to do, is to just start by saying, I’m going to start having open, frank, and honest conversations. I also tell people, don’t be afraid to have those conversations with everybody in your life. Talk to people about what’s going on. I talk about menstruation all the time. You can ask me anything you want to about my menstruation. I also tell my students, stop hiding tampons and pads when you’re going to walk to the bathroom. Stop hiding them in your hands or digging them deep in your pockets. Those are the things that we have to destigmatize and to demonstrate to a young person as they’re going through this moment that you’re going to stop the world for them if you need to. It doesn’t have to just look like a prescriptive sort of indigenous ceremony, which I think comes from a real historical connection to what we’re doing. It can also look like, I’m going to have a real moment where I’m empowering you as a young person, and I’m going to have this conversation, and I’m going to celebrate it, and I’m going to always be open to your experience with that.

AA: Well, Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy, I am so, so grateful for this conversation. I’m grateful for your book, I learned so much from you, and I’m just so grateful that you joined me on the podcast today. Thank you so much.

CRB: Thank you!

it was our turn to tell this story,

and we needed to make sure the story was ours.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!