“What does it mean to be uniform? What happens to all these different peoples?

Amy is joined by Dr. Farina King to discuss truths of American genocide and explore the tragic history behind Native American boarding schools.

Our Guest

Dr. Farina King

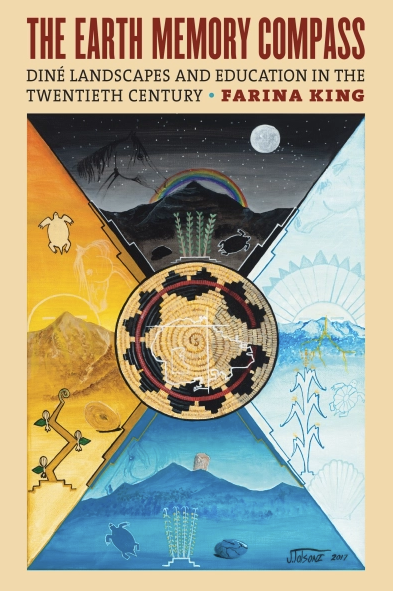

Farina King, a citizen of the Navajo Nation, is the Horizon Chair of Native American Ecology and Culture and Associate Professor of Native American Studies at the University of Oklahoma. She received her Ph.D. at Arizona State University in History. King specializes in twentieth-century Native American Studies, especially Indigenous experiences in boarding schools. She is the author of The Earth Memory Compass: Diné Landscapes and Education in the Twentieth Century, and co-author with Michael P. Taylor and James R. Swensen of Returning Home: Diné Creative Works from the Intermountain Indian School. She is one of the series editors for the Lyda Conley Series on Trailblazing Indigenous Futures of the University Press of Kansas, and she co-hosts the Native Circles podcast with Sarah Newcomb. She is the past President of the Southwest Oral History Association (2021-2022). Previously, between 2016 and 2022, she was Associate Professor of History and affiliated faculty of Cherokee and Indigenous Studies at Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, in the homelands of the Cherokee Nation and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokees. She also directed and founded the NSU Center for Indigenous Community Engagement.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In 2020, U.S. Congresswoman Deb Haaland, who is of the Laguna Pueblo Nation, and Senator Elizabeth Warren proposed the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policy in the United States Act to redress attempts “to strip American Indian and Alaska Native children of their Indigenous identities, beliefs, and traditional languages, to assimilate them into white American culture through federally funded Christian-run schools, which had the effect of cultural genocide.”

I am sad to admit that if you had asked me prior to 2020, I would not even have known what Indian boarding schools were, let alone would I have known what our country’s policies had been regarding them. Like many white Americans, Canadians, and people around the world, I only learned about the existence of Native American boarding schools when stories broke in major news outlets in 2020. And they exposed terrible abuses of Indigenous American children, even including mass graves where children had been buried.

We mentioned these breaking stories on our season one episode on Paula Gunn Allen’s book The Sacred Hoop, because these stories were so tragic and shocking to us. But they were not shocking to Native American communities, who had been subjected to the trauma of boarding schools for more than a century. And here to talk about Native American boarding schools and other related topics is Dr. Farina King. Welcome, Farina. We’re so excited you’re here.

Dr. Farina King: Yá’át’ééh, thank you. Nice to be here.

AA: So excited to have you here. I’ll read a formal, professional introduction of Dr. Farina King, and then Farina, I’ll ask you to introduce yourself a little more personally in a minute. But for listeners who haven’t heard, Dr. Farina King is a citizen of the Navajo Nation. She is the Horizon Chair of Native American Ecology and Culture and Associate Professor of Native American Studies at the University of Oklahoma. She received her PhD at Arizona State University in History. Dr. King specializes in 20th century Native American studies, especially Indigenous experiences in boarding schools. She is the author of The Earth Memory Compass: Diné Landscapes and Education in the 20th Century, and co-author with Michael P. Taylor and James R. Swensen of Returning Home, Diné Creative Works from the Intermountain Indian School. And that’s the book that we’ll be focusing on today and anchoring our conversation in that book.

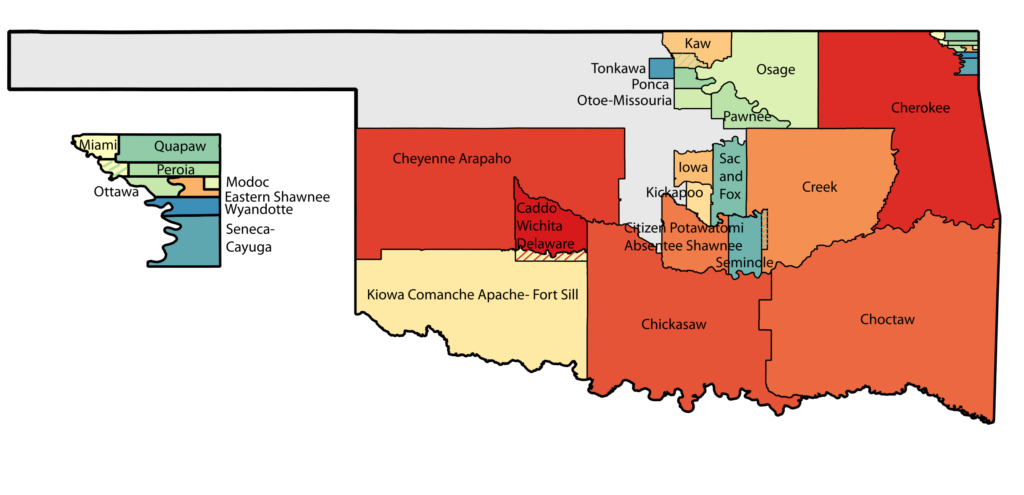

She’s the past president of the Southwest Oral History Association. And previously, between 2016 and 2022, she was associate professor of History and affiliated faculty of Cherokee and Indigenous studies at Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, in the homelands of the Cherokee nation and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokees. She also directed and founded the NSU Center for Indigenous Community Engagement. And did I say all of those words correctly, Dr. King? I hope I did.

FK: It’s the United Keetoowah band of Cherokees. Yeah, I work a lot with them. They’re wonderful and it’s an opportunity to help people. I understand their story, too.

AA: Thanks for correcting me. So if we could start by having you introduce yourself a little more personally, tell us where you’re from and some of the things that led you to the work that you do today.

FK: Sure. In Navajo, we always introduce ourselves by our clans. It helps people to know where we’re from, our relations. We call out to each other in that way, and it really is our family history. That is what we say even before we introduce our own name. Shí éí Bilagáanaa nishłí̹ dóó Kinyaa’áanii báshíshchíín. Bilagáanaa dashicheii dóó Tsinaajinii dashinálí. Ákót’éego diné asdzáá nilí.

I am a white English-American descent through my mother and born for the Towering House clan and Black Streak Woods Clan of the Diné, and I’m a citizen of the Navajo Nation. My clans are what make me a woman, is what we say. A woman or a man or how you identify. And I was born in Tonanizdizih, which means Tuba City, in Navajo Nation. My father worked for the Indian Health Service, so I grew up between the Navajo Nation and the Washington DC area, because that’s where the headquarters of IHS, the Indian Health Service, is based. And they serve Native American health throughout the country, including, of course, Alaska. And they work with Indigenous peoples throughout North America and the Pacific Islands.

And that is an important part of my background because I grew up knowing about all these diverse peoples, knowing that there’s many tribal nations and having connections with my own family and community in Diné Bikéyah, Navajo Nation. But knowing that we’re really different from other places and peoples. And in the Washington DC area, I was fortunate to meet people from all over the world. So I was recognizing from a young age that I’m not Indian, because one of my good friends is from India and her family are from India. And seeing those differences, but also similarities in human experiences. I was always passionate about learning different languages and cultures, and I loved traveling from a young age, seeing different places and building connections, making friends and family along the way in life.

So I think that has really inspired me in my work. Most importantly, everywhere I’ve gone, I’ve found myself to be an educator. Because I’m often one of the first people that many meet who identify as Native American and have the background and family ties and experiences that I have. And it often surprised people when they met me that I don’t look like the stereotyped Native Americans that they’ve been fed in Hollywood films and all kinds of misrepresentations of Native Americans, or just static images of them that they received in school or wherever in popular culture and media. So from a young age, no matter where I was, when I was explaining where I was born, where my family’s from, it was informing and educating a lot of people.

And then when I go to my family and home communities in Navajo Nation, I’m also bringing exchange with them and dialogue to them because I’m telling them about my experiences in the Washington DC area and my travels throughout the world. Where that’s taken me and what I’ve learned and shared, and how my conversations with so many different people bring new light to a lot of issues and experiences that my family have always faced. Like what you shared in the opening about boarding schools and boarding school stories, and all those complexities of it. So that’s a bit about me and how I tick, I guess.

AA: Fantastic, thank you so much. I’m also wondering if you could give us the lay of the land before we dive into your book and before we talk specifically about boarding schools. If you can give us a little bit of a bird’s eye view of the history, it could be just Navajo Nation or of even a broader Navajo scope of European contact with the indigenous peoples of North America, just so we have some context before we dive into how boarding schools came to be.

FK: Foundationally, what I tell everyone, History 101 or any beginner class introducing Native American and indigenous studies, especially in the context of the United States, is that there is not just one Native American. There’s not just the American Indian, or whatever they’ve heard. And most often, people have been misinformed and miseducated about Native Americans in the United States and all kinds of these experiences and histories. So my soapbox, if you will, or what I stand for in so many ways, is opening people’s eyes to how important Native American history is. Especially in the United States, in North America.

it often surprised people when they met me that I don’t look like the stereotyped Native Americans that they’ve been fed in Hollywood films…

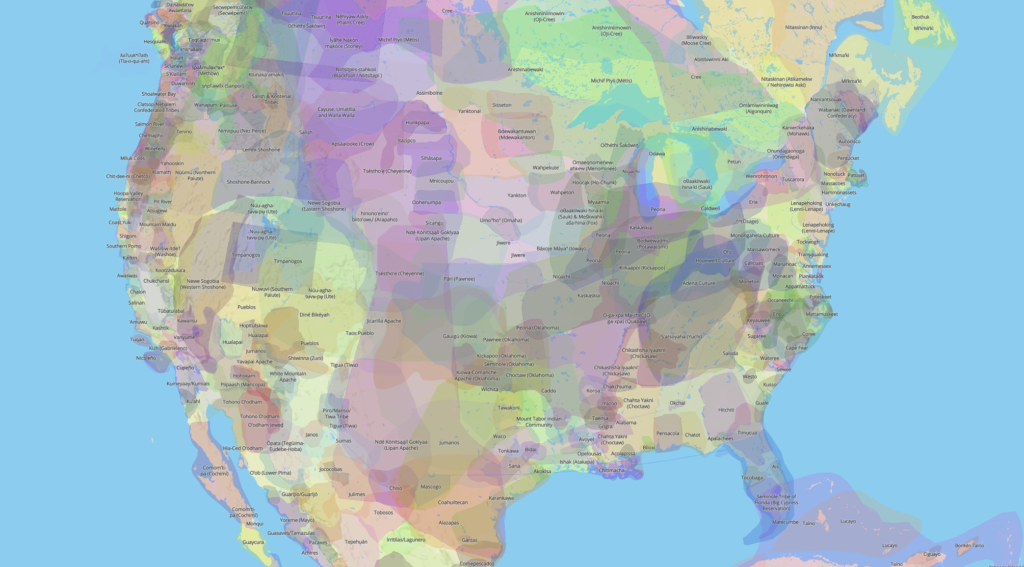

Wherever you are, there are stories that go back over generations, since time immemorial, of people who have shaped the land and the spaces where you navigate, where you dwell now. The land that we all occupy, we live, we breathe, we swim, in land and waters. And there have been people who have come and gone over all different times and generations. And that’s why, especially in the United States, everywhere what we call the U.S. is native land. It is indigenous land. That’s a basic idea that isn’t often taught, not even on a fundamental level. There are a lot of reasons for this erasure and miseducation of what I’m going to call it because of ongoing forces of colonialism. What is colonialism is a basic question, right? Because a lot of Americans think, “Oh yeah, I know about the colonial era. That was the American Revolution where Americans freed themselves from the English and declared their independence.” That’s what they think of when we bring up colonialism.

But the United States then became a colonizing power. They stepped right into it. They were already with the early European settlers and colonizers, that’s what they were. That’s also a sensitive debate right now and something to be aware of in our own words and language that we use. When we say ‘settler colonialism’, I think historically people said that because the point was that it’s not only the force of colonizing where another particular hegemony, a power, they extend their reach and they are extracting resources or human labor or anything from another place, another people, and they’re taking that to reinforce their own power. That’s a kind of vampire/extractive relationship. It is complicated because colonialism can have reciprocity. But at the same time, even if there’s an exchange that happens in some way, whether it’s cultural exchanges that happen, or economically, the power imbalance is always there. It is a kind of vampirism, a kind of monstrosity, I’ll call it, because power is flowing more in one direction.

And with the formation of the United States, it’s not even a before and after. It’s all these layers of transitions and phases that happen, but as you have the beginnings of a lot of European movements claiming for land and power, they use the doctrine of discovery and ideas of Christianity that, again, reinforce drives and justifications for colonialism. And these power dynamics, when they start to say, “Well, we are a superior race, we are superior people because we are Christian,” this idea of racial constructs and hierarchies start to form, white supremacy starts to form and it gets entangled in all these kinds of dynamics. And so these justifications start to form and fuel these power dynamics and struggles that go on.

Because when you have a people who have lived on lands, it’s homeland to them, and they know those places so intimately that it is integral to their very identity, that’s what we mean by ‘indigeneity’: is that people who are so rooted that their very existence and being is tied to indigeneity. It’s tied to that specific place and landscapes and waterscapes. It’s a key part of the way they express, articulate, see the world, the way they know things. And so that’s why we have these kinds of dichotomies start to form of colonizer/colonized, and then that becomes synonymous or equated with settler/indigenous.

And what I was trying to get at earlier with different debates is that people started to say that settler colonialism, or this divide between settler and indigenous, and that has struck some chords with sensitivities. Because even if a settler comes into what to them is new land and they’re seeking opportunities or whatever, whether they’re conscious of it or not, they become complicit in colonialism, in invasion. Where people invade an indigenous people’s homelands, their relationships, and violence often ensues because of the conflict and contestations over land and identities and all these different aspects.

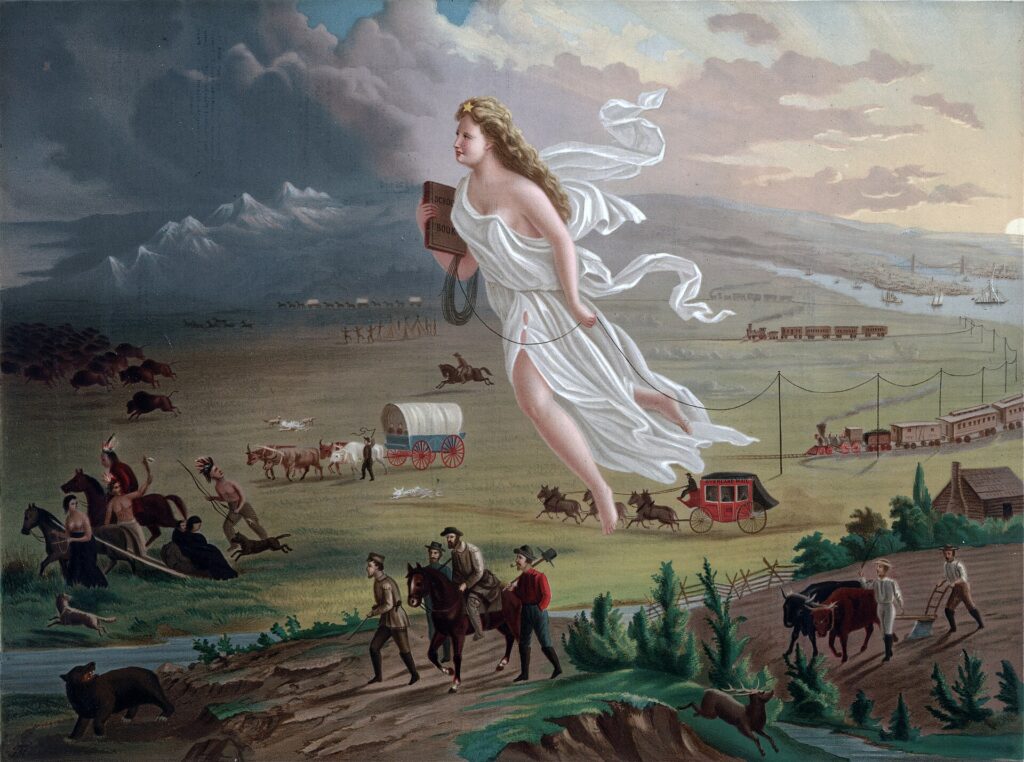

So that has shaped American history because there’s the myth, there’s romanticizing, and it’s propelled by ideas like Manifest Destiny. That is an American version of Doctrine of Discovery. Another transition is the idea that not only were Europeans justified in claiming these lands for Europe, claiming them for what they considered to be Christian nations and whatnot, but then Americans and the United States takes on this mantle, this banner of saying “We need to go coast to coast, expand and have all these territories, and unite all the land as a uniform United States.”

But what does it mean to be uniform? What happens to all these different peoples? They are people. And many Native American and indigenous peoples didn’t think of themselves– What are we talking about when we say Native and Indigenous? We’re talking about countless peoples who have very distinct identities, languages, cultures, histories, their own stories, from peoples of the marshes to peoples of the deserts, to peoples of the waterways, ice-lands, all these different places. And they are very distinct. But what happened from a bird’s eye view, as you asked, is you have this force, again of a vampire, a monster forming, of a hegemonic empire. The United States stepping into that role of an empire like England, where the sun never sets on that empire, wherever that land is. And what fuels it are these ideas and conceptualizations like Manifest Destiny, that it is destiny, it is God-given, divinely ordained, whatever have you, that this is going to happen by whatever means, and it’s supposed to happen. It is predestined.

And so these religious, even spiritual ideas and thoughts reinforce and enable these power struggles and dynamics. And the outright violence, genocide, dispossession, and what Edward Said’s work Orientalism brings into this conversation is the “othering”. That when you create these divisions of people, “these are the natives, these are indigenous,” that starts to play into the stereotypes, the myth of Native Americans as relics of the past, as if they are creatures. We recently heard on viral news, and memes shared by different Native Americans and public intellectuals, how there was a popular news channel and the newscaster had a slip-up and called indigenous creators of the popular show Reservation Dogs, she referred to them as “indigenous creatures”. And that was so triggering because even if it was a mistake, that’s what literally happened. Europeans and Americans have portrayed and called Native Americans creatures, and dehumanized them and created them as this other mystical being, something of the past that were once here but just all vanished. They’re anti-modern or what have you, all these different myths and misunderstandings about Native Americans.

Because when you know and face the truth of each, and I’m telling you, it’s waves. So many similar, parallel experiences of Diné, Cherokee, Shawnee, Cheyenne, Alaska Natives, Yupik, you can say so many different peoples and they have a lot of common ground of what they’ve been through. Of being affected by the empire of the United States seeking to expand its power, influence, and control of people. And that’s a part of the boarding school story. You have to understand that because there’s all these different tactics, strategies of that genocide. As they call it, it became a so-called “Indian problem”. That category that’s developed, the othering that happens, is they become the inconvenience. They become the problem. They’re in the way of that expansion and those claims because there’s competing sovereignties that start to form. There are people who start to reform, reshape how they view and call themselves.

That’s why we have the formation of tribal nations. When indigenous peoples met or converged with many peoples from all over the world, Europe, Africa, all these different peoples that start to converge in these spaces of North America, of what becomes the United States, when they’re starting to converge that’s where Indigenous people start to articulate in different ways, “We are a nation.” They start to shape those ideas to continue to survive. And not only survive, but seek to thrive as a people, to exist. That very existence is resistance. Because they’re standing up and saying, “We still belong to this land. It is a part of who we are. That’s what it means to be Indigenous. And we are here to remain for the many generations ahead. We will change, but we continue our traditions and have those connections intergenerationally.” And so that’s a big part of understanding all these dynamics that you’re not introduced to in the standard curriculum. And a lot of the myths are around pilgrims and Indians and the Thanksgiving story.

AA: Thank you so much, Farina. And that is true for me, certainly. I grew up in Colorado and I mean, Arapahoe Road was one of the main street names where we lived. And there were certainly indigenous words that were kind of echoes that we would hear, that would be in our vocabulary. And we learned a little bit when we would learn about state history, but almost nothing. It’s been just in the past few years. And honestly, it was a conversation that I had with my oldest daughter one time, who was way ahead of me in awareness. I went on a walk with her one time and she just started to sob and said, “Mom, do you realize that every day we live on stolen land?” And as old as I was, 40 years old or something, I had never thought that sentence before. I had lived on stolen land my whole life, and never been aware until my own daughter brought it up. And it’s become kind of a focus and emphasis in our family of educating ourselves.

We still belong to this land. It is a part of who we are. That’s what it means to be Indigenous. And we are here to remain for the many generations ahead.

How we can approach this and whoever’s listening right now, if you’re a white person who has benefited from living on stolen land your whole life, what is our responsibility? How can we make reparations for the tragedy and really the sins that our ancestors committed? But we’ll circle back to that later in the episode. I do thank you for that way to set the stage to talk about boarding schools. And if I can go into your book actually, and read a couple of quotes I thought it were really interesting as you talked about the intentions behind these boarding schools. Which were at least partly benevolent, maybe they felt benevolent to the people who are instituting these practices, though the result was still malignant.

This quote says that one of the motivations was to “cause treason to the tribe and loyalty to the nation at large, which then moves them out into our communities, [meaning into white communities] permanently disconnecting native students from their families and homelands.” And there were other quotes that I won’t read word for word, but they talked about “sterilizing Indianness” and that the goal was to assimilate completely so that Native children almost wouldn’t even know that they were Indigenous. And I was so struck at how egregious that was and how it was so purposeful. I just didn’t know. And to say that they had benevolent intentions and then read that horrifying language, to my ears it’s just incongruous. I can’t even wrap my head around it. But what are your thoughts, Farina?

FK: Yeah, I think this is a really important point. What is benevolence? What does it mean to be helpful, to be useful? Again, the language matters when we start to unpack and think about the words that we’re using and why we’re using them. Why is it so powerful to finally say out loud that this is native land and it is stolen land? What happens when that light bulb sparks in our mind? And what that can do for us, it’s eye opening and it’s so important and it’s not about guilt. I think people freak out because they think this is turning their world upside down and they’re just afraid of what all this information means. But I think it comes back, again, to when we recognize that most people want to do good. They want to make the world a better place. That’s my hope.

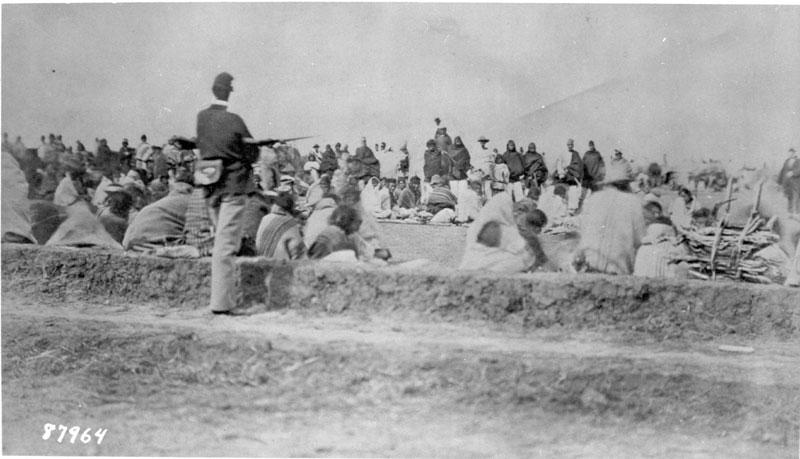

Maybe it’s naivety, maybe it’s just sheer optimism, but I think there’s a real power in that power and love and what it sparks of healing and hope and optimism and those bright aspects. So even with your question of how someone can say this is a benevolent idea, they mean well. Again you have to understand the context of where people are coming from, that individuals like Richard Henry Pratt, he is the one who said those sorts of things, who thought he truly was “saving Indians”, and he thought the way to save them was to “kill the Indian in them”. And he was a part of the military campaigns that massacred Native Americans, that massacred women and children. And there were his contemporaries who believed in that outright genocide of just wipe them out, violently, whatever way you can, starve them, burn their food, poison their waters.

And this happened to my own ancestors, and so many other indigenous ancestors, of this blatant, horrid violence. And Americans can’t say genocide. They won’t even say it. They’ll try to say ethnic cleansing, all these other things. People who are in denial of the Holocaust, you know, imagine how many people are just in denial of what happened here on these soils we call the Americas. They’re overlooking that and they can’t face that. “Oh no, you’re just trying to make us feel guilty and bad about ourselves.” It’s not. It’s the truth. Understanding the roots to all these issues and dynamics and struggles, you have to go back to these sources and understand what really happened.

Because these massacres to this day are called battles. There’s a lot of massacres that continue to be called battles, or even what I’ve seen, what has been in a lot of conversations is the Tulsa race massacre finally being called that instead of a riot. In a similar way, Wounded Knee was called a battle for so long. It was a massacre of women and children, armless, no weapons, just killed, razed down. And in the state of Oklahoma, where I currently live, there’s the Ouachita battle site. It was a massacre site. But on the plaques, everything that’s written about it still calls it a battle.

So benevolence, right? Who is saying it? What’s the context? If they’re thinking, “Oh, we were battling and actually killing the beings, dehumanizing them as animals, something to take to the slaughter, and it’s just meant to be. Then sending the children to school and raising money to get them the clothing and to set up the buildings.” That is seen as benevolence in their regard. That’s their step forward. But in the big picture, when we step back and what you’re seeing, whatever you call it, cognitive dissonance, the disconnect, I think in retrospect we can see the fuller picture. You can see the forest and the trees and be able to zoom back in and out of all this. But we understand that it’s another shape and form of genocide. It was another effort to eradicate indigeneity, to erase a people’s very being and existence, who they are as Diné, as our ancestors have called themselves.

Since time immemorial, the people and all these systems were set up to disintegrate that. And there’s still other tactics to that. That’s what we have to recognize, too, even though there has been a major shift. And finally, in the United States, as you mentioned with Deb Haaland as Secretary of the Interior, she is calling for the truth to understand what happened. Because the U.S. doesn’t even officially know or announce how many of these schools there were that were funded by the federal government. They don’t even know how many children died because of these schools, and there are over 500 that have. There are still unmarked graves. Mass graves that we don’t know about. These are children. These are people who could have been grandparents, and we’re still looking for them.

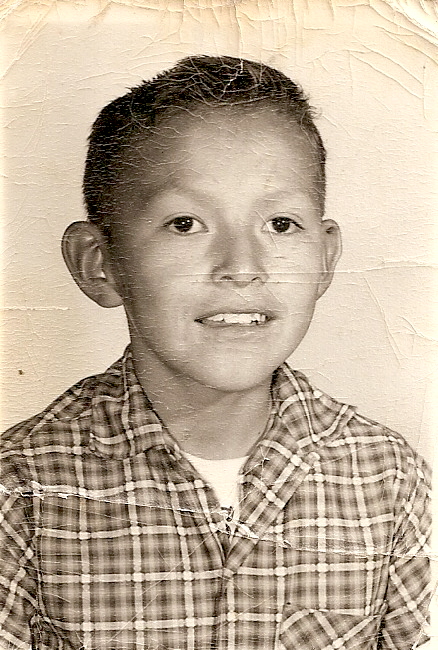

It’s very painful for me to talk about because my own dad was five years old when he was dropped off at a boarding school without warning, and immediately hit with that shock of being separated from his family, his parents, the only language he knew, Navajo language. And being punished immediately for speaking the only language he knew. And he had never even seen a toilet before, so he was curious, taking it apart. He was punished for that. And there’s just that immediate hit of that change and what that trauma was that he experienced. And he also experienced physical abuse by other boys. I’m a mother of three children, and right now I have a seventh grader. Middle school is brutal, even right now. In schools that try to support the youth, they frown upon any kind of corporal punishment. We don’t do that anymore, right? And what we hope is that it’s a more conducive learning environment and not one of fear. You can’t learn in fear. That’s a prison. That’s incarceration, is what was happening.

And my son, I’m hearing now about his experiences facing bullies and different things like that. And as someone who has heard the stories of my father, not only my father, learning those of my grandparents, my great grandparents, my first cousins, all my relatives having these parallel intersecting experiences. This has happened to whole peoples. It’s not just an exception, and this is not so long ago. This is my own father, who’s still living today, and many people who live and carry these experiences that have been happening over generations. That’s one thing too, is saying, “Oh, it just was an event. It just happened, a tragedy.” But it’s an onslaught of waves, ongoing, going and going, and still what we face as Indigenous peoples are seeking to bring the truth to light and how best to do that. Because this is so painful, triggering, and hard, but it’s worth it for us to heal and recognize the wounds. To know what to do, to know what we need to do now.

And like I was saying, my father, who went on several years after in the boarding school, tried to run away twice. And one of the times that he tried to run away, he got caught in a snowstorm and almost froze to death. I am a testament of his survival. My children are testaments of his survival. And it’s not just his survival. It’s the survival of my grandmother who was sent away to the Albuquerque Indian School. A testament of my great grandfather who was sent away to California to the Sherman Institute. It’s a testament of my great grandparents who were sent to a concentration camp in Hwéeldi, in Fort Sumner in the late 1800s when their food, livelihoods, everything just burned. And they were just living. They just wanted to live, but they couldn’t. They weren’t allowed. And they’re put like animals into a camp that cannot sustain them and dying like flies. And people don’t know this, and we don’t talk about it, and then they think we’re the Debbie downers because we’re talking about it and trying to heal.

Because that’s all I care about, is how we can reconnect when there were these efforts, just like you said, the efforts to cut off children from their very identity, from their families. We talk about human rights all the time, of basic needs, water, food. This is even deeper than that. A human right to know who you are, to know who your people are, to know your ancestors. And that remains under attack. Even right now, the Indian Child Welfare Act is under attack. As Native Americans are being framed as a race, just like every other American. This is the language, that’s the lingo. It’s a race, it’s not sovereignty, it’s not different. And they don’t take into account or know all these intricate histories. And what it means, why this is so important, why there are still Native Americans disproportionately separated from their families, placed in homes away from their cultures, their communities, their histories, and they have no idea who they are. They are lost and disconnected.

And so this is that intergenerational tie. Even when we don’t know it, we can’t see it, it’s one of ongoing pain and suffering and attacks on indigeneity, on what it means to be Native. And I say that very broadly because this is even more specific. What does it mean to be Cherokee? Jalagi. What does it mean to be Diné? What does it mean to be Nde? You know, what does it mean to be Keetoowah? All these many, many peoples.

AA: Well, thank you for sharing that. I want to really encourage listeners to read your book, also because there are so many quotes like the ones I read and topics that you just touched on as you were explaining things that you go into in a lot of detail and depth in the book and I really encourage listeners to read it. Again, it’s called Returning Home: Diné Creative Works from the Intermountain Indian School. It was so moving and enlightening and devastating to read and so, so important to read.

One of the things that I wanted to talk about a little bit more that you touched on was the connection to land. As I read your book, it became really apparent to me that I didn’t have what you were describing. And I’m actually a very sentimental person. I love nature so much that, for example, I got really, really connected to Northern California. We lived there for 16 years. We just moved from there, and I cry all the time thinking about the hills, thinking about the smells and the nature. And I was saying to my husband after I read your book, I can’t even imagine because I’m not even from Northern California. And I cry that I’m separated from it. I chose to leave. We moved because we wanted to, because we felt it was right, and we had autonomy. We chose to leave. I’m not even from there, let alone having my ancestors be from there.

And you write in your book about a different connection to the land than I had ever considered before, not just that a person is from a place, but that it’s part of their origin story, part of themselves. Like you’re connected to the mountain that you come from, and you know that your ancestors and their ancestors were connected to those mountains. Could you talk a little bit about that, Farina, because when we talk about boarding schools and this ongoing and recent separation of a person from their homeland, that’s traumatizing to a person’s psyche and spirit in a way that I hadn’t really understood until I read your book.

They just wanted to live, but they couldn’t. They weren’t allowed. And they’re put like animals into a camp…

FK: That is one of the most painful and, I mean, it’s hard for me to even find words for it. The pain and the suffering of all the forms of removal, that you can remove a person even without physically moving them. But you can also seek to physically remove them. And that’s what I meant by waves of the attacks of parallel experiences of indigenous peoples of that very deep and powerful connection that indigenous peoples have to land. That they’re not tourists on the land. They’re not visitors, it’s a part of who they are. It’s a part of what it means to be Diné that I know the origin stories of the four sacred mountains, that I know the mountains and I know they are archives, they are churches, they are so much more. They’re not just a landscape or a landmark.

It’s so multi-layered. And the journey in life is learning more and more about that connection and those deeper layers of meaning. That my ancestors carried and developed and grew in their knowledge and understandings, even just the medicinal purposes of those mountains or the spiritual meanings and practices and ways of being. That in Diné word and conceptualizations, there wasn’t religion. It was being Diné. It’s a part of who you are on a physical and metaphysical or spiritual level, and all these things were interconnected. A term that a lot of indigenous scholars are talking about lately is “relationality”, of how important relationality is to many indigenous peoples.

Again, we have to be careful of not using blanket terms and saying all indigenous peoples are this way or that way, because there are so many countless peoples that we can call indigenous in a way. But they are very distinct and have their own experiences, cultures, and languages. So I have to always reiterate that, but say that in my experience, an ongoing learning journey is that I am amazed by how many different indigenous peoples I have connected with and learned about. And there are similarities in the value of relationality and interconnectedness. When we say ecology, we think of the environment and the relationships in the environment. And you might combine human ecology, but in indigenous communities, there’s not really this divide of the human world and the environment. These are these relationships. It’s all a web and it’s entangled and inseparable.

Those ways of knowing and ways of being, that is what was so threatening to European and later Euro-American, or American imperialism and empire, and colonialism. That’s what’s so threatening, because the people cannot just be moved here or there. They cannot stand by as the land is ripped apart or used in this way. Of course they were always using the land, that’s how we sustain life and livelihoods. It’s not like they never touched the land or didn’t use it or develop it. So that’s what also I think is so important in these conversations is I often hear people say, “Native Americans never touched the trees or the earth.” They romanticize these ideas. Or they might say something like, “Protect the wilderness, keep the wilderness wild.” Well, for Native Americans, it’s not wilderness. It’s home. It is homeland. And they see that direct connection. How do you treat your home? Is that where you bulldoze? Is that where you pump the sludge and you don’t care because if it gets dirty, you can just leave it or burn it? No, these are homes that we want to prepare for the seven generations ahead that we care about.

Full interactive map available here.

So I’m really grateful you brought up this point because this is coming out in my forthcoming work. My ongoing work is connecting the dots of how my own family is from an area of Church Rock, New Mexico, Navajo Country. And there was uranium mining that started to really explode in the area after World War II, the Cold War era set in, and my family was directly affected by that. Cancer became widespread, diabetes, all kinds of health disparities, water contamination. My father, where he was born, our family doesn’t even go back to that space. Even when we are taught that you place your umbilical cord where you want to always be drawn to. Where is home? Where are you always going to be affiliated and connected to? That’s why when you ask someone “Where is your umbilical cord buried?” you’re asking them where they are from. That’s what it means to truly be from somewhere and have those intergenerational connections. And because of these colonizing forces, when people treat the land as something to take from and not the reciprocity or thinking about sustainability.

This is again, another destructive form of removal. My family is living on this land, but they can’t live on land where the water is poisoned and contaminated. And they can’t live on land when they’re dying. And they didn’t even have anything to do with that. They’re not the ones digging up the uranium. Even though there are many Navajos that were employed digging up the uranium. But in my case, many of our relatives were not. And this is happening around them, and it’s forcing our people to leave their homelands, and people are going to cities, they’re going to suburbs, finding jobs, moving for work, all these different things. So that’s another part of the conversation as well. There have always been comings and goings, movements, diasporas of peoples. But even with those movements, people know where they’re from. They know their origins. They remember, they sustain those familial ties and relationships. And it’s amazing with technologies and the possibilities of what that will mean now and into the future.

AA: Thank you for that. I’m really glad that you brought up uranium mining because you just mentioned it in your books, but it sounds like you’re continuing to write about that topic, so I’m really glad you brought it up. I’d love for you to talk about what the Intermountain School was, and if you’d be willing to share this poem that was included in your book. I feel like that poem would have broken my heart no matter what, but having that context of what the land meant, especially the trauma of leaving someone’s land, it really informed and enabled me to feel that poem differently. So tell us about the school and maybe you can tell us a little bit about this poem.

FK: Yeah. So as we were talking, boarding schools were a strategy to remove children away from their home, pipeline them into so-called mainstream American society, and after World War II, Navajos were being targeted specifically. Because at that point in the 1950s, very few Diné children even went to school. Most of them were still being raised by their families, speaking Diné Bizaad, the Navajo language, and knowing the culture. But it also was a time of much desperation because of the major transformations of Diné people and their economy, their ways of life. I won’t have time to get into it here, but we talk about that more in the book Returning Home.

And so it’s a part of that context that there were desperate circumstances of Diné people. There was mass starvation, lack of jobs and opportunities on the reservation, and there’s a broader context to that, like I said, that you need to look into with the book. But it pushed Navajo families, leaders, and community to look for strategies of survival. And so they began to see schools as a possibility for that survival, even if it was a place where their children could have shelter, water, and food, and the opportunities for jobs that they could be trained for.

So Inner Mountain was proposed by one of what we call a terminationist policymaker at the time. After World War II there was a big drive to relocate Native Americans, again, away from their ancestral homelands into cities, integrate and assimilate them. And so there were relocation policies being passed, and this aligned with an effort to terminate tribal nations. To disintegrate their sovereignty and break down treaties, essentially, that were made nation to nation between the United States and the tribal nations. So this is after World War II, and you have a group of politicians known as terminationists. And I tell you, when you even say that, terminator, termination, these are again renditions of attacks on indigeneity and indigenous peoplehood. Even when people frame it as benevolent, this is for the good of Native American peoples, they’re overlooking the very roots and sources of the issues to begin with.

So a terminationist, Arthur Watkins, proposed transforming a military hospital that was used during World War II into a mega federal Indian boarding school off reservation in Brigham City, Utah for only Navajos. It opened in 1950 and it became one of the largest federal Indian boarding schools, with as many as 2,000 students at a time. It opened in 1950 and ran until 1984. In its last 10 years, they transformed it into an inter-tribal boarding school. But for those first couple of decades, it was Navajo only. And that’s a big reason why our group decided to focus on it. I was already looking at and tracing Diné educational experiences in the 20th century, so I heard about a lot of Intermountain stories and connected with alumni and descendants of the boarding school survivors and alumni.

And it was really impactful and powerful for me because I learned how diverse and varied stories are of boarding schools. And I was surprised, like many people, of how active the alumni are and even nostalgic a lot of them are, that gather and they are proud of their experience. So I had to grapple with what that means that they were sent to these systems that had the outright, very blatant goal of assimilating and detribalizing them and getting them away from their homeland. But they found moments of joy and very crucial parts of their growth and upbringing.

And that made me realize actually how powerful that is that they were resilient, that they still have strong attachments to Diné Bikéyah, Navajo land. And that they are Diné, that they still speak the language and connect and heal together when they gather, and that was really amazing for me. Of course, there’s a lot of stories that are still said in the corner, off the mic, painful experiences, and so much complexity to it that I’m still working with alumni to this day on how to share these stories. How to navigate all these dynamics of boarding school experiences. And it’s not only Intermountain. Like I said earlier, we’re talking about hundreds of schools that have yet to be understood and the diverse experiences and what happened there.

AA: I wonder if you could share two poems that represent two different experiences from these children that were taken from their homes to Intermountain.

FK: I think it’s great you helped to highlight some poems, and one of them is Tacey Atsitty’s poem that we received permission to include. Tacey did not go to the school herself, but she is a descendant of boarding school survivors and she’s a Diné poet. And I think this is a really great poem to highlight how Diné reflect, through generations, what this means to them, these boarding school stories and experiences. This is what Tayce wrote:

“Dad says he remembers the first time he died. That long bus ride when they took him to Utah for school. He had been memorizing land formations. An angel the size of his hand disappeared and after that he was so empty from crying and so full of remembering rocks, he just fell asleep.”

And then I want to read to you Sammy Billy’s poem, ‘White man, poor man, beggar man, chief’. Sammy Billy was a student at Intermountain, and we were very fortunate to work together, especially with the collection at Utah State University that they’ve cared for our students. So many of these collections of student creative works, their art and poetry. We also reached out and worked with a lot of alumni and I was able to create oral histories with them, and I’m still doing that with intertribal students. So this is one from Sammy Billy:

“I came from the Navajo reservation to the government school where they’re going to educate me to the white man’s golden rules. I am learning very quickly. I have learned shame, humility, and honesty. Although they call me Sam, I have an Indian name. They think they can change me by cutting my hair to meet school regulations. Will they think I’m white, quarter-blood, half-breed, or Indian? Let me tell you, Mr. Teacher, when you say you’ll make me white, in many years of fighting, not one Indian has turned white. While you say that I knew nothing when you brought me here to school, just another empty Indian, just America’s first fool. But I can tell you stories that are dusty, dried, and old. In the shadow of their telling walks the thunder, proud and bold. Great Indian leaders of long ago who bet on Custer’s soul are dead, yet they are living with the great Geronimo. Well, you may teach me this land’s history, but we taught it to you first.”

I’m really glad you highlighted these two because on one hand, you have what Tacey Atsitty shared of her father’s death of that long bus ride, the separation, seeing the land change in front of him and disappear. And that’s a moment of physical detachment happening even when his heart and so many of those students are still tied to homeland and what it means to be Diné in this specific instance with Intermountain in those early years of only affecting Navajo students at first in that way. And then Sammy Billy, who like Tacey, is bringing in a critical voice. That’s what I love about them, is they show us, like Sammy says, he’s not a clean slate. He is not an empty Indian. And he is recalling all the traditions, the knowledge that he carries as a Diné young man and talking back and saying, “We taught you this first. Acknowledge that, see that, and know that I’m not going to turn white, and you can’t brainwash me, you can’t erase me.”

And so that was what was so beautiful and powerful from looking into these students’ pieces. This is written in that moment where they are being drilled at school and separated physically, and they are calling forth home, memory, kinship, those values of relationality that matter. And they’re positioning and standing up saying they are not going to forget that. And to me, that helped me to understand why I exist today. And why Diné, why we are who we are today and why it’s so important to speak, to share and tell our story and teach our children. This is what matters too, because they often don’t understand why are our grandparents like this? Why are our people like this? Why do we face these kinds of challenges? And we don’t know who we are or where we are right now unless we understand this history and these dynamics. That is going to help us to be oriented and to remember to turn to the mountains and those teachings that our ancestors treasure, and we do too, and that keeps us connected and is the future. Something for everyone to recognize is that we are in the future. We’re changing, we’re growing, but we have that hope for the future and that is healing.

AA: I have one last question. If listeners go and read this book and other books and feel grief and guilt about what has happened on this land, knowing that we’re the descendants of people who caused this terrible harm, what can we do now to make reparations? To show up for Native communities, especially if we think locally where we live, perhaps starting there, what are some things that we can do now?

FK: First of all, like I mentioned, I exist because of this colonialism. We all do, right? We’re children of this world. Whether we have control over it or not, we are. We’re all shaped by these dynamics, no matter who you are. Native, non-Native, whatever background you have, if you identify white or not. I am part white, I am white-passing. So, I think about this all the time. It’s a part of me that’s inseparable from me and many of my relatives. And I also am in these societies that are predominantly non-Diné. They’re non-Native. They don’t identify in that way. So I am thinking about this all the time. And I think it’s hard to say in the snapshot, you know, this is the answer. This is what we all need to do. But at the same time, it is simple. It’s very simple.

One is to keep learning, because it is a constant learning journey. I am still learning so much about my own people, Diné and Navajo Nation, and I’m learning so much, especially where I am in Oklahoma, home to 39 federally recognized tribal nations, and then there are so many people who are not federally recognized. And why that is, what does that mean, and what are all these different identities and stories? Embrace that passion for learning, and learning takes humility. We will make mistakes, so don’t be afraid of saying I’m sorry. Don’t be afraid of flipping up sometimes, as long as you embrace that, you recognize those mistakes, you stop, and you reevaluate, you learn. And that’s a part of learning too, is that it doesn’t go in one ear and out the other, it really needs to sink in, take time, revisit, practice, talk, learn from different people, get that feedback.

There’s a lot of really great resources at our fingertips, unlike any other time before. These podcasts, books written by Native American intellectuals and scholars. And pay attention to that, because people often talk about issues of positionality. What does that mean? Issues of identity fraud, pretending to be Indian when you’re not, and what does that mean? So watch out for that, because you really want to listen to people who have strong ties with indigenous communities. They are recognized by their own people and they work with their people. So do watch for that because it is sad that it doesn’t matter who you are, everyone needs to support Native American and indigenous peoples and communities. Because these are peoples who have carried this knowledge of land since time immemorial, and that knowledge is still there. But we need to be worthy of it. We need to prove that trust, and that it’s not just like, “Oh, I’m here now to make up for the sins of the past. Trust me now. I won’t hurt you now.” No, you have to build that trust. It takes time. It takes effort.

So listen to those Native communities. They are present. They have websites. Now they have tribal offices for cultural resources. They are calling for support in legal affairs or in language revitalization. There’s the need for the resources to back up and support indigenous communities and their initiatives that are really awesome. And they already have great momentum going. Even with boarding schools right now is a crucial time. We need everyone to pay attention and get on board and to help here. Because there are bills being presented to Congress. So call your Congress people, call your representatives, hold them accountable, and ask them to pass these bills like H.R. 5444 that is to support a truth and healing commission of Congress looking into and providing those resources that are necessary to understand the truth of what happened with federal Indian boarding schools and those impacts. Pay attention to what’s happening with the Supreme Court. Look at politicians, the people you’re electing. What are they deciding with these kinds of issues? Are they voting against teaching the truth in history classes? Teaching about Native American history and intersectionality and critical race studies? People are framing those as bad and scary words when no, these are eye-opening for us to heal and to move forward and to really be anti-racist and to uphold indigenous sovereignty with respect and honor.

it doesn’t matter who you are, everyone needs to support Native American and indigenous peoples and communities.

So we need people on board, paying attention to these conversations, and helping to educate others. This is not fear-mongering, it is about understanding these dynamics and why it matters, why we need to be teaching our children from K-12, from the young ages even, the truth. And people often say it’s too traumatic, I don’t know what to say, but there are great resources out there. Debbie Reese has a wonderful blog about American Indian children’s literature. So there are ways to introduce this to your young kids, even to yourself. Baby steps are important. But there is a call with the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, it’s a long name there, but they have a website and they have really great resources about boarding schools specifically and the need right now to call representatives to encourage them to pass these bills and to support this work.

Also, I will have to plug this in, I mean, there’s just so much, but support the Native public intellectuals who are doing this difficult work. There’s not a lot of resources out there. What I mean by that is that we need to have more support for Native American and Indigenous studies programs. I’m at the University of Oklahoma. We need to encourage all students, not just Native American students, to be taking these classes. There should be ethnic studies required at not just college, but in high school, and ways to train people in curricula and support the development of resources and publications. I’m now a series editor for the new Lyda Conley series on Trailblazing Indigenous Futures with the University Press of Kansas. I’m really excited to be a series editor for that, but I have to tell you, the University Press of Kansas was on the chopping block. There was talk about even closing down this academic press.

So please go out and buy these books from the presses directly, support this production of knowledge and these conversations, because those are even at risk and not having the support of education is at risk. So we need people on the ground really backing up all these different initiatives. There’s so much, so thank you for asking me that. And I really pray and hope you all take this seriously. What are you doing at your local schools, in your local communities to actually support education and learning? It is work to learn and it takes resources and efforts, but that learning is crucial. Because we don’t even know square one without understanding what has happened in the past and what are these dynamics today, and really upholding the platforms and the initiatives that are already spearheaded by tribal nations and communities. So, thank you.

AA: Thank you so much. I’m so grateful for all of those action items, and we’ll list all of those on the website in the show notes so that listeners can take notes and then choose one or two or three things to do. So, thank you so much for ending with that. I can’t thank you enough, Dr. Farina King, for being here today. I learned so much from you. Thanks again.

FK: Thank you for inviting me and giving me this opportunity to share all these experiences, stories, and hopes that we can really come together. I believe in that synergy. And I appreciate you all, and bless you and wish all the best for you. Ahéhee’.

What is benevolence?

What does it mean to be helpful, to be useful?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!