“being ‘feminist’ or ‘liberated’ does not always look like ‘being American.'”

In this episode I’m joined by phenomenal guests—Liz & Cami—two Americans who have lived in Saudi Arabia for the past several years and are ready to speak about their experiences navigating Saudi patriarchy as foreign women. Their conversation is fascinating and funny, discussing dress codes and driver’s licenses and the shadows of colonialism in this unique peek into one of the world’s—allegedly—most patriarchal societies.

Our Guests

Liz & Cami

Liz (she/her) & Cami (she/her) are decades-long friends who live in Saudi Arabia. Both are busy pursuing degrees (Liz in Global Public Policy, Cami in Sociology), taking Arabic classes, and trying to decide what to make for dinner. Liz loves subversive cross-stitching, thunderstorms, and lemon-flavored desserts. Cami loves reading, listening to podcasts, and cuddling her dog.

a discussion with

Liz & Cami

Cami: Hi, my name is Cami, and my pronouns are she/her.

Liz: And my name is Liz, and my pronouns are also she/her.

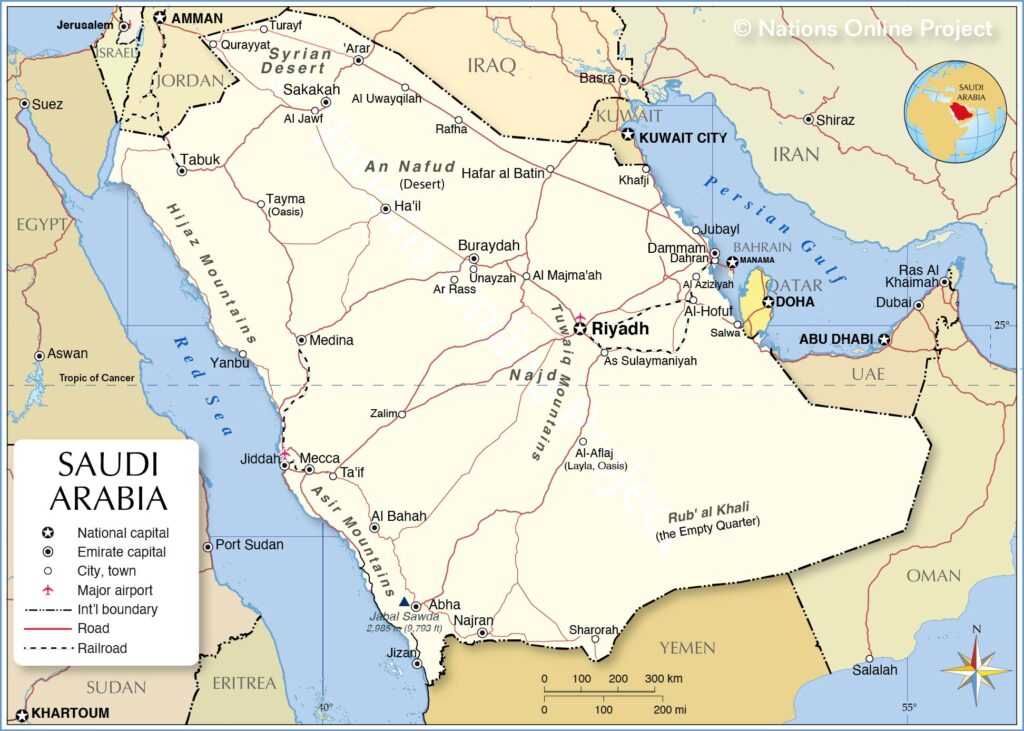

Cami: And we are talking to you from where we live, in Saudi Arabia. Which is a hot, sandy, culturally rich, fascinating place that is much more fun and complex than you probably think.

Liz: Yes! I think people have some strong assumptions about Saudi Arabia, given what they often see or hear in the media, and I certainly did before we moved here. And living in Saudi Arabia as American women is an especially interesting experience. But before we get into it, why don’t we tell you a bit about ourselves.

Cami: I’ll go first! I’m Cami. I was born in Tucson, Arizona, but spent most of my childhood in Washington state (Seattle area). I am number four out of eight children; six girls with two bookend brothers. We were a traditional Mormon family and growing up I never actually thought about how others thought we were totally weird, until my mom and dad bought our family a 15-passenger van. That’s when I felt like I had to explain our situation to kids at school. It was the party bus for sure. I have a lot of fond memories of my childhood, and as much as I sometimes wished I was the only child, I liked being a part of a big family. From my family I learned values like responsibility, gratitude, service, forgiveness, and other essential skills like how to negotiate at the table for the last breadstick. As we will talk about more later, my family also had a profound impact on my ideas about womanhood and feminism, and my personal development as a woman.

The summer after high school, I moved with my family to Logan, Utah where my dad relocated for work. Later that year, I met my husband, we dated for four months and then got married. I was 19 and he was 24. Looking back, we cringe…we were so young and dumb and knew nothing about life, but we still really like each other today, so thankfully it has worked out. Just after getting married, we moved to Chicago, and just after celebrating our first anniversary, had our first child . . . not intentionally, but it happened. Then, before we understood what was happening, we moved two more times (first to Indiana for my husband to attend law school, where Liz and I met, and then to Wisconsin) and had three boys. I had a really difficult time adjusting to: 1. Adulthood, and 2. Motherhood. Coming from a conservative, traditional Mormon family, the messaging I’d received from both home and church was that my worth, as a woman, was tied to my roles as a wife and a mother…it was what I was made for. Essentially it was my moral obligation to support my husband and it was his moral obligation as a man to be the breadwinner and provider. So, we prioritized his education and career while I stayed home and raised babies. During that time, I also worked as a hairstylist (an education that my parents supported me pursuing because I could do it from home and still maintain my essential wifely duties). I liked being able to spend time with my clientele, building friendships and having meaningful interactions with some really great people who I still think about today. In a lot of ways this was the place where my curiosity for people (why they do what they do and what social forces shape their lives) was sparked, which has now led to me returning to school and pursuing a Sociology degree.

Liz: I’m Liz! I am the oldest of four children and was born to two born-and-raised Mormon parents, and we moved around a lot when I was a kid. I grew up, broadly-speaking, in the southeast of the US, but when I was 12, my family moved to Mexico City and I stayed there until I graduated. After that I went to our church’s religious university, called Brigham Young University, where I got my bachelors degree in International Studies and Development. Growing up, I always felt like because both of my parents were raised in the Washington, DC area, and tended to be more politically liberal and less culturally Mormon than most people we attended church with, that I was less affected by some of the more harmful aspects of belonging to a patriarchal church. I had big dreams of studying to become a heart surgeon, I wasn’t sure I ever wanted to get married, and I for sure didn’t want to have kids. But, after a few years at BYU—which is a very, very conservative and traditional university—I got married to my husband, and at 21 I had abandoned my dream of becoming a surgeon. We eventually had our first child. Somewhere, and I’m still not entirely sure how this happened, between when I graduated from high school and when I got married at 21, I came to believe that you could either have a job as a woman, or a family, but not both, and that one choice was significantly more righteous than the other. So, after five years of marriage, I quit my work-from-home job as a social worker and we moved across the country for my husband to start law school. And a year after I got there, Cami and her family moved in next door!

Cami: Liz and I were next door neighbors in Notre Dame student family housing. Being so close in proximity and having the shared experience of being young stay-at-home Mormon moms with busy law student husbands made becoming friends easy. Supporting a husband in law school while raising a child was often a lonely experience. But we tried to keep ourselves busy with playdates, book clubs, taking care of the kids, and bringing husbands meals as they worked late in the school library. Liz was a part of my support system, and I think that was the case with many people who were in this student community who were also away from home. When I got pregnant with my second child, Liz was training to become a certified doula and I was one of her first births. She was fantastic, and through that whole experience, she saw parts of me that, I think, naturally bond people together…like watching me poop on the delivery table.

Liz: So, we were close, but…eventually, our lives diverged—Cami and her family moved away for a job, and we moved away for a job, and separately started our own journeys of discovering feminism and how patriarchy informs our lives.

Cami: The messages told to me growing up, within church and family circles, was that feminism was a sort of bad word; something I needed to keep my distance from because what “those people” were advocating for was something that would not only threaten my faith, but our way of life and how it was structured (or at least what our God and his prophets taught). My sole role and purpose was bigger than anything feminism seemed to make women want (or at least that is what I was taught….I didn’t understand what feminism was or what it really stood for outside of voting rights and equality in the workforce). In fact, we had a large print document on our wall called The Proclamation to the World on the Family, which was a church statement made back in 1995 by official Mormon church leaders outlining the official church positions on the role of family, marriage, and sexuality. Words from that document were reinforced at home and in church lessons, the belief that “Mothers are primarily responsible for the nurture of their children,” reinforcing gendered expectations and roles of women.

For a long time, I was afraid to identify as a feminist, especially out loud in my heavily patriarchal religious community. I was worried about how others would perceive me, if they would see me as less faithful, if I would disappoint my family, and if I would disappoint God. I don’t remember really when I became a feminist, but I remember being surrounded by incredibly thoughtful, smart women in a book club during our time in South Bend. Among many, I remember one book in particular that sparked something within me…it was Anita Diamant’s book, The Red Tent. This is a historical novel about Dinah, who was the daughter of Jacob and Leah in the Bible. I don’t know what it was really, but something about hearing a story about a biblical character that was a woman affected me. Through my whole life, we told and were told stories about men. My college education has helped me gain the language to articulate more of what that means to me and how that has affected me. Once I turned that part of my brain on, it didn’t turn off. I couldn’t stop noticing gendered norms and expectations within my faith community and the institutional structure that was designed in a way that kept women from participating at the same level with men in high positions of administration and authority. This led me to a very long and uncomfortable process of deconstructing my faith, and discovering new ideas and beliefs while also developing and broadening my feminist perspective through feminist writings and podcasts. My experience here has been an eye-opener to me that there is not one, but many feminisms that fit with particular cultures and traditions.

Liz: I think I had a very basic idea of what feminism was prior to having kids, but it was very much a vague idea of fighting for women’s rights, and generally more applicable abroad in countries where I perceived women to be “oppressed.” I remember writing an essay about what was called “female genital mutilation” for one of my classes and being horrified by the idea of gender-based violence, but I wouldn’t say I was well-versed in how issues in feminism could and did affect my own life. But while my husband was in law school, and I was bored at home and trying to navigate being a young mother to now two young kids, I was introduced to the concept of religious feminism. I had been having a broader identity crisis after having kids—who was I, and who was I supposed to be? Was I supposed to throw my entire self into raising my kids at the expense of my own goals and interests? Or could I somehow maintain my sense of self and still be a good mother? I started reading blogs written by Mormon feminists, and listening to podcasts and hearing women put my own struggles with identity and power into words felt so liberating and I felt so heard. And so I started the very slow and very painful process of deconstructing both my faith, and how it informed my values, as well as my identity as to what it meant to be a Mormon woman. And one silver lining of my faith deconstruction was that I became very good at understanding and sitting in cognitive dissonance—I could hold two conflicting ideas at the same time, and understand that one idea being true didn’t necessarily mean the other was false. I considered myself to be a nuanced, liberal member of my faith—I didn’t believe everything that was taught (and frankly disagreed with several hot-button issues, including the church’s vocal opposition to same-sex marriage) but I believed that there was good inside of it and that I could work to make things change from the inside better than I could from the outside, because by maintaining my membership and participating, I was granted a certain level of legitimacy and soft power that I wouldn’t have if I left. So in 2014, I started blogging for one of the Mormon feminist blogs and raising my voice about what I felt could and should change inside the church.

I had a very basic idea of what feminism was….a vague idea of fighting for women’s rights, and generally more applicable abroad

Fast forward to February 2018, and my husband gets an email from a headhunter looking for an attorney at a company in Saudi Arabia. Since I grew up overseas and really valued that experience, he was always keeping an eye out for overseas legal opportunities, but within minutes of receiving this email, he responded, “thank you for thinking of me, and while I would be interested in an overseas position, Saudi Arabia is not the right fit for my family.” Ha! And then he forwarded it to me, almost as a joke, because he figured there was no way that his now self-identified feminist wife would even consider moving to Saudi Arabia, which in our minds was the poster child country for the oppression of women.

Cami: I remember when Liz announced her move to Saudi Arabia, and I thought, “Wow that is crazy! I would never do something like that.”

Liz: It was crazy, but between my husband’s work situation in Michigan not being ideal at that particular time, and a general feeling of “well there’s no harm in asking questions and looking further into it,” we asked for more information, and talked to some people who lived in Saudi Arabia, and one thing led to another. And after a lengthy application process, my husband was offered the job, and we accepted. I definitely still had conflicted feelings about the whole thing. We were told from the beginning, not only by the company itself, but also by people who worked there, that it was difficult to be a woman in Saudi Arabia. When we were applying, women still couldn’t drive. I was told I wouldn’t be able to legally work because of my visa status as a “dependent woman.” I was told I’d have to wear an abaya, which is like a loose-fitting, long-sleeved dress, whenever I left his company’s more Western compound. And Saudi Arabia was not exactly known to tolerate dissent or differing opinions—my agnostic sister said she might take up praying again just to try to keep her loudmouth feminist sister out of Saudi prison for shooting her mouth off when she shouldn’t have. Literally everybody around me was like “really?? You?!!?” But for me, I was like, “look, I have grown up in a patriarchal, conservative church, and I have made it work! I have come up with new frameworks for how to experience patriarchy without it destroying me! I have basically been training for this my whole life. Living in Saudi Arabia is like running my religious feminist marathon.”

Cami: And six months after Liz and her family moved to Saudi, we were talking to the same recruiter. I remember I was walking out of class, Steve (my husband) called me and asked what I thought of moving to Saudi Arabia. I laughed, and said we are not as brave or adventurous as the Johnsons. For context, I had never travelled outside of the United States, save one trip to Canada for a weekend, so my confidence in my ability to navigate a foreign country was nearly zero. To add to that, the only thing I knew about Saudi Arabia was what was reported in the news…which was not great. I especially didn’t know how it would be, being a woman. I had all sorts of conflicting feelings. Of course, with anxiety being my constant companion, I imagined all sorts of horrible things that could possibly happen, but also saw it as an opportunity for all of us to experience something unique that would stretch our world view. I had people say to me that they weren’t sure I could handle it. To be honest, I wasn’t sure I could handle it either. But I’ve always been interested in people who live differently, so there was a curiosity there. Even though I hadn’t traveled a lot, and my social circles were still within Mormonism, I was curious to know what that life would be like, both for other people, but also for myself. But this is also another time where I was going to have to delay my own goals, to put my own dreams and aspirations aside and follow my husband and support his career. At the time I was attending classes, working towards a degree. This was something that would be good for him, but for me, it felt like a step backward.

After months of back and forth, talking to Liz and her husband, we finally came to the conclusion that “why not?” We knew we could always make the decision to come back if we decided we didn’t like it there, and it was an opportunity that we didn’t want to pass up and regret later. We were in a phase with our kids where they were young enough that it would be a relatively easy (and I laugh at this word now) adjustment. And it was a real adjustment for all of us in different ways. For one, I think living here has provided a new perspective of how it feels to be an outsider, a foreigner. It has certainly been a humbling experience recognizing that in a foreign place, we are definitely the strange ones. This awareness of your foreignness can be uncomfortable at times when you don’t want to stick out. But I say that also with a full recognition that we live privileged lives here compared to expats from other countries. For the most part we are treated well and we are respected compared to others who face real obstacles and social barriers in Saudi society. It’s hard to describe our experiences here in Saudi…words range from wonderful and full to confusion and frustrating. All the things really, and sometimes all in the same day. Being a woman comes with another unique perspective because of the social and institutional structures in place that shape our experience in day-to-day activities.

Liz: I still have trouble putting the experience of living here into words. It’s so many things, like you said, and it was an enormous adjustment. I thought that since I had grown up in Mexico and had traveled internationally, I would land in Saudi Arabia and be totally fine. I expected that things would be different, but I would adjust seamlessly. But landing here for the first time… it was a lot.

Cami: Nobody can prepare you for the shock of landing in Saudi Arabia. Some things you expect, but I didn’t expect to see women’s faces blurred out on billboards or advertisements.

Liz: I still remember the first time I saw a woman’s full face without being blurred on a billboard, probably six months after we got here, advertising that women could now apply to get driving licenses, and I was completely shocked! It’s crazy how quickly I got used to seeing them blurred out, and then to see one unblurred felt like a really big deal. And I still notice it when women’s faces are used in advertising here, because that’s pretty new. Although stores still will often use a sharpie to draw clothes on the women on packaging, like for pool floats or costumes, if they’re showing a little too much skin.

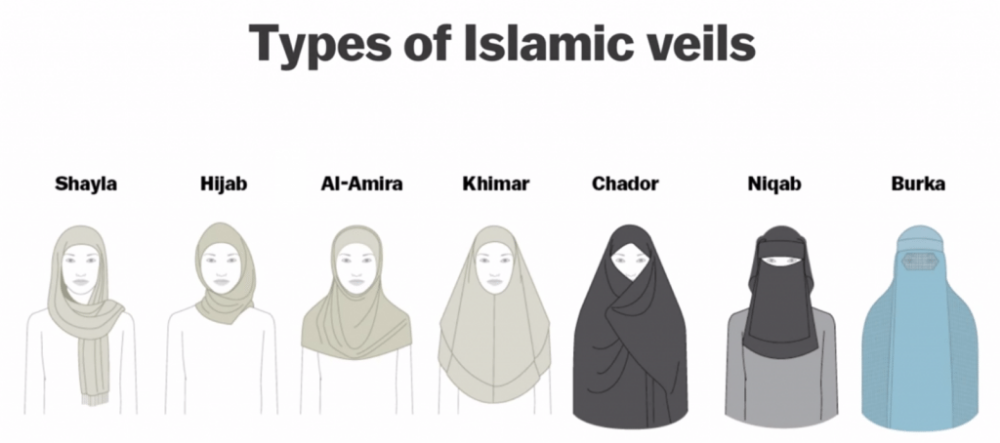

Cami: I will admit that it was shocking to walk through the airport for the first time after our family landed, and seeing women dressed in black niqabs. I felt so exposed with my face showing and looking like an outsider. I was wearing a dark grey maxi dress that covered my arms and chest, but once I saw what all the other women were wearing, I was thinking, “yeah my dress is too tight” and walked to the baggage area with my arms crossed over my chest.

Liz: And in addition to just the visual shock of landing here, I couldn’t perform the most basic tasks when we arrived because I was a dependent woman. Tasks that I would normally do for our family in the US, like setting up utilities or getting cell phone plans, were tasks that my husband had to do. Even signing my kids up for sports, or signing myself up for a community class—my husband has to do those things. When I withdraw money from our local joint bank account, he gets a text saying I have withdrawn money. Even on my company ID, it specifically says, “dependent,” which robs me of my ability to do certain things. And as somebody who has always prided herself on being capable and independent, being dependent has been a real ego hit.

Cami: And even though I have done all of these things in the US, there is something about the air we breathe here that makes me feel like I can’t do those things here. Even driving to the store off of camp or running errands; I feel like I can’t do that on my own. I need my husband for that. Even if I can legally do it, it feels almost impossible to do on my own. And it makes me feel like I truly am dependent on my husband, even for things I know I can do. There is like an added layer of being aware that if I were to be pulled over or in an accident, or if I got lost, would I be capable or would someone help me, or would the person I interact with be ok with me as a woman? And also a woman who’s not covered up, would someone have a problem with that? And a lot of people don’t, but it’s a concern I have.

Liz: Right, and it’s a legitimate thing, because there are a lot of people who don’t take us as seriously! I remember when we first moved in, and I was trying to get somebody to help us with repairs on the house, they wouldn’t take my requests until they “talked to boss.” Like for anybody here, I am “ma’am,” but my husband is “boss.”

Cami: And you know what, sometimes we reproduce this. We use it to our advantage sometimes! Like if we get someone who knocks on our door who wants something, like when we first moved here, a gardener wanted to work for us, and I didn’t know how things worked, so I told him I had to ask my husband, and he was like “yeah, no worries! I understand!” And he left. And I’ve used this several times to my advantage, because people understand that I wouldn’t be able to make a decision without asking my husband. That he has the authority. And I hate that I do this!

Liz: No, I do this too! And I also hate it! But sometimes it’s just the way to be able to get out of something because that’s how the social norms work here. And we’re playing the game with the cards we have been dealt, for better or worse. BUT we have had some feminist victories. By the time Cami moved here, women were legally able to drive. And so it felt like, for our own feminist credibility, we needed to try to get our licenses.

Cami: We should be clear that since we have valid American driving licenses, it was a different process than it is for most Saudi women. When they finally allowed women to start driving here, demand for spots in women’s driving schools exploded, and so there is still a significant waiting list for local women to get their licenses. Since we have valid US licenses, we only needed to get the paperwork attesting to their validity, and pass a simple driving test.

Liz: On the surface, this process is the same one that our husbands had to do when we first arrived in the kingdom. Just make a copy of your license, have it attested, go take the test. And actually, they didn’t even need to take a driving test. And the company organized it all for them—it was a guided process. Right? It took our husbands, what, a day and a half to get them?

Cami: Probably not even that! But for us, as women, there were several more obstacles. We had to get our licenses not only translated and certified by the Ministry of Commerce, but we also had to pay a local lawyer to attest to having seen the actual license. And we had to figure this out on our own—there was no guide to getting a license as a dependent woman. We were following social media posts where other women would share their experiences and trying to piece together the process, and it was constantly changing and everybody was always confusing so we were just praying that somehow we would check all the boxes that we needed, even though they kept adding boxes. And we also had to hope that the people we were interacting with would help us.

Liz: So after we got our licenses translated and attested in one place, then we had to take that attested copy down to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, for another attestation, I assume saying that the lawyer who attested our translations was a real attorney? I don’t know.

Cami: And then, while men could get license appointments locally, we had to take an entire day to drive to the traffic office in Riyadh, who had to view our documents and make separate appointments for the driving test back in our local area. And even in Riyadh, do you remember how lost we were? We were in a government facility, with military men everywhere, with guns, and we didn’t speak much Arabic and we didn’t know which building to go into, and I accidentally went into the men’s bathroom at one point and thought I was going to be deported! It was such a mess! And then, we found the room where we needed to go, but it was this tiny room with no sign on it, with three women inside, in this small space. I mean, it was a small miracle that we figured it out.

demand for spots in women’s driving schools exploded…there is still a significant waiting list for local women to get their licenses

Liz: And let’s not forget that going to Riyadh is not easy, because Riyadh is a four-hour drive, each way. And keep in mind, we are not legally supposed to be driving to any of these appointments. Which would theoretically mean having our husbands drive us, which wasn’t always possible because many of these offices are only open during work hours, so it meant hiring a driver to take us to each place. And that cost adds up. Unless you’re willing to just… risk it… and drive yourself… and, well, no comment there.

Cami: Anyway…once we got our appointments, we then had to go to the driving school to take our test. And before we could take the test, we had to have our documents reviewed, AGAIN, and then finally, we had to present them to the only man at the driving school for his final approval. Of course. And he was in this massive room behind a huge desk, and everything looked so official. It was so intimidating. But he stamped our papers!

Liz: And then we had to go take the driving test. I think the test was driving forward, making a U-turn, parallel parking, and then reversing into a parking spot, which I was totally not prepared for and not very skilled at! Also, there were no backup cameras.

Cami: I actually hit the curb. I was sure I was going to fail. It was nerve wracking, to have done all of this work and finally be at this last step.

Liz: Yes, and another friend was with us through this whole process, but when she got into the car with the woman who was testing us, our friend told her she was nervous. And the instructor woman put her hand on our friend’s knee, and said, “don’t be nervous, we are not in the business of failing women.”

I can’t even tell that little anecdote without getting emotional, because seriously, that felt like the first part in the entire process that wasn’t in the business of trying to fail women! We had jumped through so many hoops and it always felt so precarious, like we would miss one little thing and have to start the whole process over again.

Cami: And we had friends who tried this same process shortly after we did, and then ran into all sorts of obstacles that we didn’t face! Sometimes it still feels like a miracle that we got our licenses. It took us a full six weeks of actively working towards it. And we’re lucky, because we are American women with US licenses—the process was even more opaque and arduous for women from India, for example, or Brazil. At one point we heard that it wasn’t even possible for women from certain countries, or who looked a certain way, because their local licenses weren’t considered valid for this process.

Liz: And this brings us to the interesting place of being American women here, which is a very different experience from being a Saudi woman here, or a Filipina woman here, or even a Canadian woman here. Our US passports, our whiteness, and our economic situation afford us a level of privilege that makes our experiences here unique to us. We’re still very much affected by the patriarchal structures here in Saudi, but we are also afforded tremendous privileges and advantages. Like one thing we did after getting our licenses was go on an all-female road trip to see some archaeological sites that were several hours away. And it required us driving on our own, and booking hotels for ourselves, and trying to find clean public restrooms for women, and it felt incredibly empowering to do that kind of thing here, even though that’s something that I would do without a problem in the US. But also, it feels ridiculous to say that, because I think it feeds the notion that this place is somehow backwards or less developed in comparison to the US, and I don’t think that’s the case. It makes it really difficult to talk about our lives here, because I don’t want to feed the stereotype of women being oppressed here, but also, sometimes little victories feel really big in the face of the structural barriers.

Cami: And one thing that we have both been thinking a lot about is how Saudi women are perceived and talked about. We both came to this country assuming that Saudi women are The Most Oppressed Women in the Whole World, but we have found those attitudes to be rooted in Orientalism, a Western lens, coined by Edward Said, that perceives Eastern cultures as backwards, mystical, passive, regressive, and barbaric. This reinforces a stereotype of a Saudi woman as a passive figure, exotic, dressed from head to toe in black without voice or passions, when in reality the situation of women here is far more varied. All of this is made increasingly more complex as Saudi society continues to liberalize, norms change, and Saudi women continue taking a more active role in society (even if that role is not necessarily one that would be seen as impactful in a Western sense but aligns with their own values). Living here further emphasizes the importance of understanding that there is not one approach to feminism, but many feminist approaches that are unique to different cultures with unique historical contexts.

Liz: Obviously we cannot speak to the experience of Saudi women here, as we’re not Saudi women. But there’s not even a singular Saudi woman experience to be told. The experiences of women here are multifaceted and extremely complex. But even for me—an American—just trying to navigate my life here feels like I’m constantly doing this weird dance with patriarchy. Like, when I leave our compound (which was originally designed to keep Westerners and their influence outside of Saudi, but has become more integrated into the community in the last 10-15 years) the decision of what I wear off camp is fraught. Up until 3.5 years ago, there were laws about how women had to dress in public that included wearing an abaya, which again is that loose-fitting dress that is long-sleeved and goes down to the ankles. And there were actually religious police who had the authority to enforce this, and your abaya had to be long enough to cover your ankles and loose enough that you weren’t showing any of your shape, and they could issue citations or bar you from entering places like the mall or a restaurant if you weren’t in compliance. But now, the religious police are gone and the only rule is to “dress modestly” off camp, but there are no guidelines for what that means for us. So… like… what does that mean for me? The abaya is definitely the safest choice, culturally speaking. But also, it is approximately 1200 degrees here in the summer, and so wearing a black dress that covers my entire body isn’t exactly appealing sometimes. And also, sometimes it feels a little suffocating—like it’s emblematic of how difficult it is to live here. Sometimes it feels like I’m literally wearing the patriarchy when I wear an abaya.

Cami: And there are ways to make the abaya a little less hot, like maybe wearing less clothing underneath it. But even inside the camp, there are people who come here from all over the world, and many of them are coming from other cultures that value that expression of modesty, plus there are also Saudi families on camp. So even on camp, when I’m in my exercise clothes and I go for a run or on a walk with my dog, I’m conscious of my body. Like if I’m wearing something too tight, or too revealing, and whose house am I going to be walking past. I think about that more than I did in the US.

But there are some things I like about the abaya! Like if I’m wearing something really frumpy that day, I can just put an abaya over my sweatpants, and I’m covered up and appropriately dressed! And there are some really gorgeous abayas and ways for women to express themselves and their culture through the abaya.

Liz: I admit to going to more than one fancy restaurant in my pajamas, with my abaya over them. And it is the best! I love wearing my pajamas to dinner!

Cami: And here, it’s most common for women to wear a black abaya with a niqab, which is the veil that covers the nose and mouth, so only the eyes are showing. And this is something that sets Saudis apart from other cultures in a way. It’s something unique here and unique to how they perform gender here that is distinct to their culture and their identity. And there’s such an obsession about the women’s clothes here, and it’s the first thing that people ask me about living here. They want to know if I have to cover my hair (I don’t), and actually covering hair here is almost a statement of religious significance. Like that is an expression not just of modesty, but also of faith, so it would almost be inappropriate from my perspective since I’m not Muslim.

But even in our own religious community, Mormonism, there is an obsession with what women wear. And it’s something I’ve had to deal with my whole life. A woman’s clothing isn’t just clothing, it has a moral value to it. It’s almost like people can tell your values from how you dress, and your commitment to your faith shows in how you dress. But even here, there is something about wearing an abaya off camp that maybe gives me some credibility, and they see me wearing an abaya, and that says something about me. That I am willing to conform to the cultural expectations here.

Liz: Yeah, I think about that a lot, because there are times when I will go off camp in pants, and a shirt, and a long sweater that covers my bum, which is definitely meeting all of the legal criteria of dressing modestly because I’m covered in loose clothing to my wrists and my ankles, but is definitely not the norm here. And again, it’s a dance, because how do I navigate wanting to feel authentic to myself and my values and what I want to wear as an expression of myself against the desire to be respectful to the culture here, and not wanting to feel like I’m making some sort of statement that could feel like a value judgment on other women’s clothes? Like if I go out in jeans, am I saying that I think the abaya is oppressive? Or am I just saying I felt like wearing jeans that day? It’s something I think about a lot, and it’s something I will do in certain spaces and not others. Like if I’m going out to lunch with other Western girlfriends, and we’re going to a cafe that’s known for being a hotspot for Westerners or generally more progressive, then I am more likely to wear jeans and a sweater, but if I’m going into the souq, or near a mosque, I am definitely wearing an abaya.

Cami: Even the abaya feels like a political statement. I was reading an article about when the Taliban were overthrown in Afghanistan in 2001, all these people were expecting women to take off the burqa, but they didn’t! Some didn’t. For those women, wearing the burqa was an expression of femininity, and also an expression of their community that showed a set of shared values.

Liz: And also, assuming that women would take off their burqas implies that women weren’t choosing it to begin with. The expectation that women would change their dress when the rules change seems to assume that these women aren’t active agents in their own lives who make their own choices. And that feels rather paternalistic and colonialist. There is a huge conflation with how Muslim women veil themselves and an assumed lack of agency that is so problematic. Like I think that if you asked Mormon women, for example, whether their religious undergarments are proof of their oppression and a lack of agency, they would be incredibly insulted. For them, wearing their religious clothing is a choice they’ve made to signify a degree of religious devotion, belief, and commitment. Why do we assume it’s not the same for Muslim women?

Cami: Yeah, why do we assume Muslim women are inherently submissive? There is so much talk about what Muslim women wear, whether it’s the hijab or the niqab or the burqa or whatever, as though Muslim women aren’t making choices or aren’t active agents in their own lives. But you really don’t hear people making that same critique when Western women are ordering their salads with the dressing on the side, or excessively exercising or getting plastic surgery to fit an unrealistic body standard that makes them more acceptable to Western patriarchal norms. Like even here, at least for me, I definitely had a superiority complex when I got here, and I hate saying that, but I felt like these women would want what I have. It feels so arrogant to say now, and I hate that thought.

Liz: Yeah, it’s almost like, if these women were liberated, they would look and act and dress more like me. Which is so arrogant, and I hate that I’ve ever thought that way, but it’s definitely something I’ve felt. Living here since has made me realize that being “feminist” or “liberated” does not always look like “being American.”

Cami: And that’s what justified colonialism, too! It’s this view that these other people are backwards, and we are free and modern, and you want what we have, and so it becomes this takeover and erasure of culture. I think it’s a little bit inherent to being American; the belief that ours is the best way, and the right way. And it’s all part of neoliberalism, like we will come and open up your markets and progress will come, and you will be so grateful. But that has only worked out for a select few, and the results have been uneven at best, yet we’re still perpetuating this belief that our way is the best way.

Liz: Meanwhile American women are submissive in their own way. Like we both recently listened to a podcast with Manon Garcia, who just wrote a book we want to read called We Are Not Born Submissive, and she talks about how women everywhere, in every culture, are being submissive to patriarchal norms in their societies.

Cami: Yes! Like in the US, we wear makeup, and we remove our body hair, and carefully calculate our assertiveness so that we come off as strong, but not too strong, and attractive, but not too attractive, so we can be taken seriously! Or like, even with sex, the ways we think about sex, and how the media perpetuates this idea of the act of sex, ending at a male orgasm with little or no thought to the woman’s experience. But even with all of that, we believe that our American submissiveness is the best form of submissiveness, or the least submissive. As though there’s a hierarchy, and ours is still at the top. But it’s not!

Liz: Yes, because we still have this total white savior complex that we need to save brown women from the brown men who oppress them, and that we as white women know what’s best for them.

we believe that our American submissiveness is the best form of submissiveness, or the least submissive.

Cami: And I love to wear makeup! I do! I enjoy doing my makeup, and dressing up sometimes, but why do I like those things? I mean, it makes sense, because growing up, there was a reward to looking pretty. And so much of that shaped my preference for how I like to dress or put on makeup, or whether I wear makeup regularly. And I don’t know how much of those preferences are because I want to do those things, or because I benefit from doing those things! There are social rewards for looking a certain way! Even like the things we do, the activities we choose to do. I’m thinking about when I did Tae Kwon Do, which is something more masculine to do, as opposed to doing ballet, which is less cool and more feminine.

Liz: Yeah, how do any of us know why we do things? Do we actually prefer them and they align with our values? Or are we doing it because of the social rewards we get for conforming with patriarchy? And is that bad? Why are we sometimes ashamed of doing things that benefit us? Like I hate shaving my legs, but also, I don’t want to be that lady at Target with hairy legs that gets whispered about in the checkout line. But also, sometimes I like the way smooth, hairless legs feel! Why is this so fraught?! Why is so hard to be a woman sometimes?!

Cami: But this is what the gender binary does. Both men and women are conforming to things that don’t make sense. Like men and women, we are both hairy, but there’s a social benefit for women to shave their legs and armpits. And men do this too, they’ll hit the gym and do certain workouts to try to mold their bodies to look like what our culture has decided that men should look like. Never mind that our biology is not so binary and that we all have different bodies and they’re fine as they are and there’s actually a lot of overlap between women and men too. Like yes, the average woman is shorter than a man, but there are a lot of women who are taller than a lot of men! But many tall women feel disadvantaged for having a body type that is outside the desired norm.

Liz: And in some ways, I can see how women here might feel like they are at an advantage for not having to perform gender so obviously in public. There is an anonymity of wearing an abaya and/or a niqab that I sometimes envy. I would like to be stared at less in public, honestly, but between my pale skin and my four kids, I am sort of a walking circus. But I think women here are just performing femininity differently, and I think the men perform masculinity differently here, too. Like we know a Saudi man who wears very Western dress into the office, like slacks and a dress shirt, but when he needs to go into a government office, he will wear the traditional formal dress of a Saudi man, which is a crisp white thobe with a white or red-and-white printed headdress. Patriarchy just sort of slots us all into these roles that we need to perform for certain benefits.

Cami: And it’s about distinction, too, right? The gender binary is about distinguishing one group from the other, and there are different consequences for deviating from the gendered norms. And here in Saudi Arabia, that distinction is very pronounced. Like when my husband went to the dentist, people thought it was so odd that he was fine having a female dentist working on his teeth. They asked us over and over again if he was fine with a female dentist. But it just goes to show that gender is really a defining part of life here. It’s something that influences what you do and how you do things and what spaces you can participate in. I just recently discovered that there is an all-female boxing gym here in town! And all public exercise spaces for women are relatively new here, but there is a boxing gym where women can go and train, without the fear of the male gaze or having the expectation of covering up, because it’s only women. And they had loud music, and they weren’t speaking quietly. They were grunting and sweating and working out. And it felt like a revolutionary space, because women could go into this space and move their bodies however they wanted, and they could be loud and strong and could explore what their bodies could do without the constraints of gender.

Liz: And I think that some people would still find it “backwards” or “oppressive” that women aren’t able to work out in the same space as men. But I think that’s very much a Western lens on this whole thing, and we have to stop assuming that any feminist act is going to look like Western, white feminism.

Cami: I think it can be hard for our white, Western brains to conceptualize what feminism would look like here. If anything, I think that would be for Saudi women to decide, because it’s their country and their values. And there is a branch of Islamic feminism that aligns with Islamic values, which values complementarianism, where essentially women and men are equal, but operate in separate spheres with different roles and responsibilities. And it’s hard for my brain to not see that as “bad,” but I also know that there are many ways for women to feel empowered, and to feel like they have influence and voice. And that’s what living here has done for me, and for us. It’s that there’s not one best kind of feminism. That there are many feminisms, with varying cultures and definitions and priorities. And mine is not the best one. Mine is going to value different things because of how I was raised.

Liz: Yeah, I once heard the phrase “hard on systems, soft on people,” and that resonates with me in a lot of ways, because women everywhere are just trying to do their best to navigate this sticky mess of a world with whatever cards they’ve been dealt. And so what might feel like an empowering or liberating act for one woman is going to be different for others. I think Manon Garcia said in that podcast that you can’t “badass your way out of patriarchy”—no amount of “woke” or “correct” or “feminist” choices is going to free a woman from the system of patriarchy that we all exist in. But what we can do is look at the ways that we are constrained by our own culture and cultural values, and examine the ways we are submissive to patriarchy, and try to reform the system. And she said patriarchy is like a hydra, it has many faces, and that it looks differently in different spaces, and there will be unique challenges in each person’s life. But when we realize that we are trying to take on a system, rather than judging who is more oppressed than the other, I think we do better in our feminism.

Cami: And that’s what patriarchy does—it pits women against women. It’s like a whole hierarchy, with women under men, and certain types of men are under each other with a hierarchy of masculinity, and within women, there’s a hierarchy there, too. Patriarchy rewards women who conform and who uphold it and who try to keep other women in their place. And this ties back into that concept of submission, that within that hierarchy, white or western women being the “right” kind of submissive woman and belittling other women is a form of upholding patriarchy. And this is where orientalism comes back in, too, because it keeps people in a fixed state. It doesn’t allow people to progress. Like when we see a Saudi woman, the way she dresses and the way she talks and performs her gender, we don’t see her as fully human. We immediately place her in that hierarchy and don’t interrogate further. We assume she is this really religious, backwards person, without her own unique experience or thoughts or goals or aspirations. We don’t really see much other than her clothing. And in an effort to not objectify her, we continue to objectify her, and assume she’s nothing but a submissive woman.

Liz: Yep. So, long story short, we all need to do better. And examine our biases and stop being so damn judgy about everything.

Cami: Agreed. If we really want to help women, we need to look in the mirror. Before we cast judgment, we maybe need to question why we’re making those judgments. And recognize, like Liz said, our own conditioning.

Liz: I think that, structurally, we can look at our own complicity in certain things. Which is obviously incredibly uncomfortable, both because we don’t like to think that we contribute to harm, but also because we feel powerless to change it. But I think that, as western women, we could think about how our habits of excess consumerism affect women globally. Or how our eating habits and consumption contribute to climate change. And I think, from my personal perspective, we need to consider how our elected officials have made decisions in international foreign policy that have been detrimental across the globe but perceived to be in the US’ “best interest.”

Cami: And also in the media! Like in movies or shows or news articles, our media perpetuates this orientalist perspective of the US being enlightened and other parts of the world being backward. Like you’ll see those tropes of the terrorist of the Middle East, or the Arab woman who needs saving. The way we talk about Middle Eastern culture. When I went back to the US, I got all sorts of comments or questions, like “why on earth am I living in a place like this” or “are you safe there,” which is funny because I have felt very safe here. Or comments that suggest that people here are stinky or harsh. It doesn’t allow for the full human story. It doesn’t see this world as anything other than a barbaric, backwards, and stinky place.

Liz: And to be clear, people do not smell here. There is a strong culture of smelling good. And people here are kind and hospitable. And yeah, I also feel very safe here!

Cami: And we also need to recognize that our world is incredibly interconnected, and the way we talk about each other matters. And I think my hope is for us to listen to women’s stories. And my hope is that as things open up after the pandemic, we can not only listen to women’s stories, but also value them and take women at their word. Believe women when they say they feel empowered when they put on a niqab. Because some women do. And some don’t. And some have very complicated feelings about it.

Liz: Yes, because when we allow for multiple stories and multiple ways of being a woman, and being a liberated woman, that’s how we escape the narrow boxes that patriarchy keeps putting us in.

Cami: I like that. And I think that is it…recognizing that there are multiple feminisms and multiple ways to push against patriarchy in its many forms.

Liz: And I have hope. Strangely, living in Saudi Arabia has made me more optimistic for women around the world, not less, because I see the many ways that women are exerting their agency and taking more control over their lives and their choices.

Cami: Same. And I hope our stories help.

Listen to women’s stories.

Value them. Take them at their word.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!