“Women, wake up! You have a voice in the peace process.”

Amy explores the history of Liberia and Women’s Mass Action for Peace through the written words of one of her heroes, Leymah Gbowee.

Women’s Mass Action for Peace

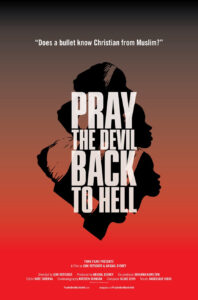

I first heard about Leymah Gbowee through a film called “Pray the Devil Back to Hell.” I had been interested in Liberia for several years already because we have friends who ran an orphan home in Liberia that we helped support by donating money and supporting one of the kids there by sending emails. So we had learned a little bit about Liberia and the devastation that had happened during the wars of 1989-2003. But I didn’t know the details, and when I saw “Pray the Devil Back to Hell” it absolutely floored me. I highly, highly recommend this film to listeners – you can watch it for just a few dollars in lots of places online. After watching the film I was so moved by the topic that I read several books on the war, including the book that I’m going to discuss today. It’s a memoir called Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War, and again, it’s by Leymah Gbowee, whose work for peace in Liberia won her the Nobel Peace Prize. I recommend buying her book, because I’ll only be able to share a portion of it today.

So let’s begin, as usual, with some historical background.

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West coast of Africa, along the Atlantic Ocean. To the north it is bordered by Guinea, to the Northwest it’s bordered by Sierra Leone, and to the East is Cote d’Ivoire, a.k.a. the Ivory Coast.

But it’s important to remember that so many times when we talk about the African continent, the borders and the names of the countries are recent inventions of European colonizers. So if we back up, before that, historians believe that many of the indigenous peoples of Liberia migrated there from the north and east of the continent between the 12th and 16th centuries CE. That’s really quite recently compared to other areas of the continent. Then in 1462, Portuguese explorers arrived, and they named the area Costa da Pimenta (Pepper Coast), because of the abundance of peppers, which became desired in European cooking.

In 1602 the Dutch established a trading post at Grand Cape Mount but destroyed it a year later. In 1663, the British installed trading posts on the Pepper Coast. No further known settlements by non-African colonists occurred until – and if you have never heard this history before, this might blow your mind – in 1821 an influx of free Black Americans returned to their African homeland, after their ancestors had been abducted and taken to America in the transatlantic slave trade.

How did this happen? Well, in 1816 in New Jersey, a white Presbyterian minister named Robert Finley founded the American Colonization Society. Of course this was right in the middle of America’s practice of enslavement, and even in New Jersey, which we think of as a Northern state, Robert Finley had grown up seeing plantations and enslaved people all around him. In 1816 there were about 1.5 million African Americans who were held in bondage (and by the way, that number would grow to 4 million by 1860). But some Black Americans had been freed, and they were having children who were free, and Robert Finley and others believed that these Black people would face better chances for freedom and prosperity in Africa than in the United States.

So when I first learned this I wondered, “is that because they were racist and they didn’t want to integrate Black citizens into white society? Or was it because they recognized the horrible sin of the slave trade and wanted to try to make things right by helping people resettle in their ancestral homeland?” Importantly, what did Black Americans want? So I did some research, and I discovered that of course it’s complicated and there are many different points of view. There were many white slaveholders who supported Black migration only because they worried that the presence of free Black Americans would inspire enslaved people to revolt. There were other white enslavers who said they might grant manumission (or freedom), except that then where would the formerly enslaved go? Their racism was so ingrained that they couldn’t imagine full citizenship and integration. Some white abolitionists thought that if there were a colony available in Africa where recently freed people could be resettled, enslavers might be willing to grant manumission and end the institution of slavery. And then there was another group of white abolitionists who were adamant that their Black fellow citizens could and should be integrated into American life and there was no reason for them to leave.

What did Black Americans want? On one hand, living in a brutally white supremacist country was not easy, and to some, it was appealing to start a new life in a new place, and especially in a majority-Black environment. On the other hand, many Black families had been in America for generations and had deep roots in their communities. It was home. And some cities and towns had thriving Black communities full of opportunity and joy that were relatively safe from white supremacists. So there was a huge spectrum of experiences and points of view.

In the end, between January 1822, and the American Civil War, more than 15,000 freed and free-born Black Americans, and 3,00 Afro-Caribbeans, relocated to a settlement in the Costa de Pimenta that was established by the American Colonization Society. These settlers suffered extremely high mortality rates in the early years from the journey all the way across the Atlantic, to new diseases that their bodies had no immunity to, to lack of sanitation and infrastructure in their new home.

The settlers carried their culture with them, which was an African-American culture. They named their new country “Liberia,” which as we mentioned last week, means “freedom,” (think of “liberty”). The Liberian constitution and flag were modeled after those of the U.S. and they named its capital city after American Colonization Society supporter and U.S. President James Monroe. The capital of Liberia is still called Monrovia, after James Monroe. The ACS asked the US government to make Liberia an American colony or to establish a formal protectorate over Liberia, but it declined to do that. It did consider itself a “moral protectorate,” intervening when European powers threatened its territory or sovereignty, which they did. This was at the height of a land grab at the African continent by England and France and other European countries. Soon though, the ACS encouraged Liberia to declare its independence, and it did. In 1847, it became the first country on the African continent to declare its independence. So it is Africa’s first and oldest modern republic. They elected Joseph Jenkins Roberts as the nation’s first president. Roberts was a freeborn Black man from Virginia, whose father was a Welsh farmer and whose mother was a fair skinned biracial Black woman who had previously been enslaved. I cannot even imagine what a life, and what a fascinating story that would be to learn more about Joseph Jenkins Roberts.

However, let’s back up and imagine how this whole thing felt for the people living in this region who had never been to the United States, and suddenly 18,000 people are showing up, saying “the American government says we can live here.” One important factor that caused huge, ongoing tensions is that the religions of the people living in the Costa Pimenta at the time were indigenous religions and Islam. And the religion of the incoming immigrants was Christian (specifically mostly Methodist).

So now we’ll jump into Leymah Gbowee’s book. She talks about this history, and writes that in addition to the people coming from America and the Caribbean, there was also an influx of African people from other parts of the continent who had been abducted during the slave trade but had managed to escape, and they were coming into Liberia as well. She explains that even for her, as she grew up a century later in the 1980s and ‘90s, she says,

“Your ancestors’ origins determined your place in the social order. Settlers who came from the slave boats – called “Congo people” – and those from America, many of them mixed blood and light skinned, called “Americo-Liberians” – formed a political and economic elite. They saw themselves as more “civilized” and worthy than the tribes of Africans who already occupied the land: the Kpelle, Bassa, Gio, Kru, Grebo, Mandingo, Mano, Krahn, Gola, Gbandio, Loma, Kissi, Vai, and Bella.”

For generations, the elite clustered in and around Monrovia or in suburbs like Virginia and Careysburg, where they built expansive plantations that recalled the American South. And they held onto power with a tight grip. The awful irony was that they did to the indigenous people exactly what had been done to them in the US. They set up separate schools. Separate churches. The indigenous became their servants. The social inequality, the unequal distribution of wealth, the exploitation – and the desire of the indigenous to take back what was theirs – are some of the reasons we had so many problems.

She continues with her story, saying “My father was a Kpelle, a poor rural boy from …Bong County, in Central Liberia. For a time, his father worked as a virtual slave in the Spanish colony on Fernando Po Island. …[he] went to the Booker T. Washington Institute, where ambitious indigenous boys could learn a trade. He became a radio technician.

Mama, also Kpelle, was born in Margibi County. …Ma had her own story. In the recent past, Americo-Liberians often went into rural villages looking for fair-skinned children to foster and ‘modernize.’ Because Ma’s skin was light, she had been chosen and brought up in an elite house. Her adoptive mother expected my mother to marry ‘up’ to a boy with money or education. When she instead fell in love with my dad, a sweet talker who was ten years older, from a poor family and unemployed, [her mother] was furious.”

I also thought it was interesting in this part of the book that Leymah talks about how her mother gave birth to three girls in a row, and when Leymah was born, her fourth daughter, she named her Leymah because it means “What is it about me?” – as in, “Why can’t I conceive a male?” (9)

Another passage that is very telling in terms of gender dynamics is that Leymah’s grandmother, the one who adopted her mother because she had fair skin, was “quiet but very strong, [and] very respected in her village. She spoke with absolute authority; when she put her foot down, no one crossed the line.” But on the other hand, she goes on to say that when this woman’s son came home from school, he would “order her around, demanding ‘where’s my food?” And for this mom to kind of be his servant. So, men’s sense of entitlement that women will serve them is a major theme in the book. It comes up over and over again on every level of society, from sons to their mothers, and brothers to their sisters, and husbands to their wives. And especially there’s a theme of husbands expecting sex whenever they want it, and turning to violence when women push back in any way.

But back to the political story: Americo-Liberians had been ruling the country since its founding in 1847. In 1980, Americo-Liberian William R. Tolbert was the president, but then, a member of the Krahn tribe whose name was Samuel Doe, staged a military coup. And Gbowee writes about this episode in history:

“Samuel Doe, then an army master sergeant, seized power. Tolbert was disemboweled and shot, and the next day, thirteen members of his administration were publicly executed on the beach. Doe, a Krahn, was the first nonelite president of our country, and his coup was supposed to mean the beginning of a new era of fairness for the indigenous people of Liberia. ‘The native woman has borne a son, and he has killed the Congo People!’ his supporters sang. (By now, “Congo people” referred to anyone who was elite.) Doe got generous financial support from presidents Reagan and Bush, who wanted to keep Liberia as an ally during those Cold War days, and who liked that he opposed the Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi. But Doe proved corrupt and violent: he stole an election, pocketed hundreds of millions of dollars, and tracked down and killed his political enemies.

…she named her Leymah because it means “What is it about me?” – as in, “Why can’t I conceive a male?”

…It was during Doe’s rule that tribal identity began to matter. Before Doe, the split was between the elite and the indigenous. All of us had our tribal identities: our dances and traditions, our native languages. But we were equal to each other, and tribal intermarriages took place all the time. Doe changed that, awarding all the jobs that came with money and power to his fellow Krahn. Some ethnic groups, like the Gio and Mano, were excluded from politics completely. Bitterness, then opposition, grew. By 1989, the opposition was led by a man named Charles Taylor… who bragged that he was taking Monrovia and that his National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) would ‘get that boy Doe off the backs of the Liberian people.’ Taylor was a member of the Gola tribe on his mother’s side, and the Americo-Liberians on his father’s side.”

At this point in the story, Gbowee was 17 years old, and she describes that the country was in chaos and there was terror everywhere. People trying to escape would be stopped and asked where they were from and what ethnicity they were, and if the soldiers didn’t like their answer, they could be shot on site. Bombs were going off constantly, and young men calling themselves “Taylor’s boys” were roaming the streets, unchecked. These were young boys and teenagers – also called “Small Boy Units” of soldiers – who were recruited to be soldiers, given AK-47s and drugs, and told to rape and kill other ethnic groups. Gbowee and her family and a lot of their community took refuge in what they called The Compound. This was St. Peter’s Church and it also had a bunch of other buildings around it, because it was believed that soldiers would have respect for the sanctity of a religious building. She describes what happened next:

“One day, Doe’s soldiers heard that there was food at The Compound and goods to loot. They came for us. It was a Sunday morning. My mother was in the upstairs chapel at a church service and the kids were having Sunday school. I was cooking when the treasurer pulled me aside and took me to look out his bedroom window. Soldiers were pushing their way through the front gate. I came outside to look. They had already put one man staying in The Compound, the local director of police, into their pickup truck. Now they surrounded the main building. “Everyone downstairs!” the commander, a man with ceremonial markings of the Krahn tribe drawn in chalk on his face, shouted through the front door. “Everyone outside!” The children came down the staircase, frightened, but chanting the way they’d been taught to do when the war scared them, “Jesus! Jesus!” The words made me angry. God won’t help you, I thought. “Face the wall.” We lined up near the door. The wall was rough, bumpy. One of the women could not stop crying. “Jesus!” she sobbed. “Shut up,” ordered another soldier. He also had chalk lines on his face and a thin cord tied around his forehead with a piece of coral in the center. “Leave her alone!” The cry came from the woman’s sister, Mirtha. The soldier slapped her across the face. Without thinking, Mirtha slapped him back. He raised his gun, as the man standing next to my mother switched the baby he was holding to his other arm, and fired. The bullet passed through Mirtha and hit the man’s raised hand, which had just moved to block my mother’s face. “I’m shot,” he said, and Mirtha dropped. She had two children.”

Leymah goes on to describe the horror of that day as the soldiers kept threatening them with rape and murdering them, and she just kept thinking we are never gonna get out of here, we’re dead. But then, a family member showed up at the church and said “I’m here to get my sister and her family,” and the soldiers asked what tribe he was from. He told them, and for whatever reason the soldiers let him take out a few members of his family, and Leymah was among them. They took shelter in an apartment nearby and tried to get some sleep, just sleeping on the floor, and didn’t know what had happened in the church. They thought, again, that the soldiers would respect the sanctuary that’s offered by the church. And I’ll read a passage here.

“When President Doe’s army had begun going after members of the Gio and Mano tribes, the Liberian Council of Churches made a conscious decision to offer asylum to people in danger. They believed that although the soldiers were brutal, they would fear to commit violence in a house of God. Close to a thousand men, women, and children had ultimately taken refuge in St. Peter’s chapel and the adjoining high school. But on that night, a different government battalion had carried machetes and machine guns and pushed their way inside. Among the pews where we sang and prayed, where on Women’s Day husbands and children pinned flowers on their mothers clothes, they raped, slashed, shot, and hacked. The Gio and Mano inside had pushed open the doors and run out into gunfire and there were bodies on every street corner. Men, women, babies. I saw dead and bloody pregnant women. A dead man lying with his dead child in his arms, the baby bottle still in his hand.”

She goes on to describe how mass violence was unleashed all over the country, with tribes fighting other tribes. A man named Prince Johnson became a leader, kind of a warlord, and was in opposition to Charles Taylor. Everyone was recruiting children, many of them orphaned by battles and organizing them into these special units, the Small Boy Units which I mentioned before. And they called Charles Taylor their “papi” like their dad. And she says:

“Just as it had happened elsewhere in the world, in Bosnia, Rwanda, Kosovo, some balance had shifted and decades of repressed rage poured out. Nothing would be the same.”

So people are escaping from Liberia as fast as they can, trying to get to somewhere safe. But Leymah’s family didn’t know where to go. They ended up leaving and going to Ghana, and actually stayed in the same refugee camp where Veronica Fynn Bruey had stayed, that she talked about last week. And the scenes of horrible, horrible violence that were happening in Liberia and also Ghana among the refugees is just so harrowing to read, and I’m not going to read some of the more violent and upsetting passages. But the overall sense is this horrible sense of destruction. Destruction of life, destruction of innocence, destruction of people’s peace of mind and physical, mental, spiritual, emotional health. And then just the destruction of property and the waste of time, money, and energy in this senseless destruction. And Leymah Gbowee does such an excellent job of writing this in a way that you feel this sense of tragedy. She says that,

“In the end, Charles Taylor was held off from taking the country, though neither side really won. In two months, more than 6,000 people had died, most of them civilians. The country had been destroyed by the conflict. But the fighting mostly stopped, and life went on.”

At this point in the story I want to mention that alongside the Liberian wars, Leymah also tells the story of her personal life. And I want to mention two important parts that I learned from.

First, Leymah talks about a long-term relationship she had with an abusive man, who became the father of her children. This is such an important part of the book, because Leymah had been a brilliant kid with so much promise, and she says that when this older guy showed up she knew he was trouble from the very beginning, and she doesn’t know why she allowed him to wear her down and get her into a relationship with him. He ended up abusing her in every way – mentally, emotionally, physically, sexually. And she says that as she kept getting pregnant and having these babies, whom she loved so much, she ended up destitute. She ended up impoverished with no support and she felt the shame of her family so she couldn’t ask them for help. And she also felt deep shame inside and self-loathing because she felt she had squandered her potential. And that self-loathing caused a deep depression that exhausted her and made her unable to pick herself back up for a long time. I want to mention this because I think it’s important to understand, for anyone listening who has ever been in an abusive relationship or a position like this, there is hope. And this story really follows that arc, you’re inside Leymah’s head as she’s going through all of these experiences. She writes about this terrible state that she was in for years, but she kept putting one foot in front of the other, sometimes just because she had kids and she had to be there for her kids. But she was eventually able to leave her abuser and start improving her life, and she ended up getting an education, getting her joy back, and realizing her potential, and then doing work that literally changed the world. And like I said, for anyone who has gone through this or has been through this, or for listeners who know someone who isn’t living up to their potential and is struggling in an abusive situation or with crippling depression, the book is so wonderful at giving hope. And the lesson I learned is to not give up on anyone. It can happen to anyone. And the thing they need most from us is not judgment, but unconditional love. That’s what she needed. She needed people to keep believing in her.

The second part of Leymah’s story that I want to highlight is that during the period after the first civil war, where there was a little bit of a break in the fighting, she said she learned about a program run by UNICEF that trained people to be social workers who would then counsel those traumatized by the war. She says she had never considered doing that kind of work, but her kids were little and she felt like she needed to get out of the house to do something, so she asked her pastor to write a letter of recommendation for her, and to pay the application fee, she got over her embarrassment and pride to ask her dad for money. And her dad paid the application fee and she got into this program! This was the first step toward her becoming independent and getting her life back. But I also want to highlight that she discovers through social work the power of telling your story and being met with love. She talks about how really often the women she worked with would sit and cry together and just take turns talking. And having the group validate and sometimes say “that happened to me too,” just that act of speaking and listening helped them heal. I also want to share some of the questions they asked in sessions that were intended to help communities heal after fighting, because these questions and this ethos of community healing will come up later.

She says that they would ask, “What is conflict? What is peace? How does your local language and custom define it? What are the national issues that affect your village? What do you see as the cause of conflict in Liberia? What do you have within your culture that can be used to resolve it?”

She says that they learned these tools and these questions to ask from places like Bosnia, that had undergone civil war and they found themselves on the other side of the conflict needing to forgive each other for what had happened during the war, in order to heal as families, and neighborhoods, and a nation, and as a whole. This volunteer work was her first introduction to not only doing the social work on a personal level, but being a peace-builder in a whole community. She says:

“When I use the word peace-builder, I mean something much more complicated than negotiating, brokering or signing treaties. Peace-building to me isn’t ending a fight by standing between two opposing forces. It’s healing those victimized by war, making them strong again, and bringing them back to the people they once were. It’s helping victimizers rediscover their humanity so they can once again become productive members of their communities. Peace-building is teaching people that resolving conflict can be done without picking up a gun.”

And she would use these skills again and again. So back to the story. After an interlude where there wasn’t much fighting, Charles Taylor arrived back in Monrovia in 1995 and signed a peace treaty – but it was the 13th peace treaty among the warring factions and it was just as meaningless as the previous ones. The new government “quickly splintered into yet more factions, with each warlord grasping for political power that could in turn be used to generate riches.” Soon, Leymah says they started hearing guns and rockets in the street again. And this time she had two toddlers and was five months pregnant. They ended up having to run for their lives – they couldn’t drive because there were so many soldiers on the road, and these soldiers, she describes, were terrifying and you see it in the documentary film too… sometimes they would be wearing human bones. And wearing really freaky masks, and wearing really absurd things like wedding dresses and painting their faces. Just really trying to be terrifying. And it really was. And these soldiers, again these are young boys who had been taken from their communities, they had been orphaned or often they had been given drugs, trained to use machetes on people… So you can’t take your chances meeting these people on the street. So they left everything behind as soon as they saw the writing on the wall that these soldiers were gonna be in their village – they packed up the tiny little bit that they could and they left in their pajamas. And she mentions these details like her little toddler had this pillow that he needed to sleep and they had to leave it behind, and they just ran. They had to go for seven hours, and on the way trying to get to her family’s house to safety they saw soldiers with bloody machetes and they just had to run past them. She says in the movie and in the book that she will always remember her little son crying because he was so hungry and saying “I wish I could have just a piece of a doughnut.” She was so heartbroken to say “Nuku, I don’t have a piece of doughnut to give you,” and he said “I know, I just wish I had a piece of a doughnut” with such resignation in his voice that it broke her heart.

The fighting continued, and she describes the devastation of the countryside. She had always been in Monrovia prior to that, except for their time that they were in Ghana. I should have mentioned that she did come back to Liberia from Ghana, if I didn’t make that clear before. So all of this is happening in Liberia. She talks about going out into the countryside after just being in Monrovia for a while, and she describes the devastation that she saw there. And I’m gonna read this passage too:

“In the countryside, civilians had been caught between warring groups, with no safety, and everyone suffered. I saw the ruins of good cement homes, schools, hospitals and clinics. Where survivors were trying to rebuild, they were constructing houses of mud. Bridges had been blown up; we crossed rivers on rough planks or got out and walked. Fields of cassava had gone fallow. At first, villages often seemed empty; the memory of fighting was so fresh that everyone hid if they heard a car, because they didn’t know who was coming and what the strangers would bring. The poverty was unspeakable – stunted, silent children; women dressed in rags.”

Again, I wanted to share that passage to illustrate the devastation and the waste of– people had spent money building those homes, building those bridges, building those schools. She says in another part of the book, her own university was completely destroyed. Charles Taylor had used it as a base for his soldiers. Hospitals were destroyed. There was a point when there was not one hospital in the country. Just the senselessness of this dominator culture moving through the country is so tragic, and it’s really infuriating to read about and to think about.

But then there was a lull in the fighting again, and during this period Leymah continued her work as a peace builder. She was able to keep growing and learning as a social worker and she read Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi. And she talks about a Kenyan author whom I’d never heard of before, he was a reconciliation expert named Hizkias Assefa. And he “believed that reconciliation between victim and perpetrator was the only way to really resolve conflict, especially civil conflict, in the modern world. Otherwise, Assefa wrote, both remained bound together forever, one waiting for apology or revenge, the other fearing retribution.” So she began working as a counselor for former child soldiers. And if you can imagine, these soldiers had raped, and maimed, and murdered. Sometimes in the people’s own communities. She writes:

“They were a frightening looking group. Scarred, dressed in ragged, filthy clothes. For years, they had looted whatever they wanted and never learned to maintain what they had, with an air of menace. Anyone with sense who saw these boys on the street would immediately know to cross it to avoid them. Some were missing arms, some legs.”

And I won’t read the way they spoke to Leymah because it is peppered with obscenities that I can’t say on the podcast, but it’s just really obscene and really, really aggressive. But she said,

“I wouldn’t let them see my fear or disgust. Taylor’s Boys. It was Papi Taylor who first brought children into the Liberian war with his Small Boy Units. Although eventually all the rebels used them. Tens of thousands fought. Some of them as young as eight, carrying AK-47s they were barely strong enough to lift. They were a nightmare vision of childhood, these soldiers, desperate to please and too young to understand what they were doing. Taken away from their families and kept high on alcohol and drugs until they became the most merciless killers of all. I heard all about them in the workshops I led in the countryside, and I never forgot the boy I’d seen covered in blood and washing his knife the day Daniel and I fled Monrovia.”

But she continues and says, “I worked with the ex-combatants for more than two years. They had nothing. Taylor had cut them loose when they were wounded and of no more use to him. Their parents, if they could find them, didn’t want them back. They lived in abandoned buildings and survived by begging. I began running workshops for them, tried to link them to social services that might help them with daily needs like obtaining food or medicine, experimented with projects like planting gardens and harvestable crops that might suggest a viable post-war future. Sometimes there would be five straight days when the boys worked well together and made plans, and I had hope that we were getting somewhere. Then I’d get hit in the face with something murderous. “You know how many women we raped? It was one of the best games for us.” A teenager sits back, watching for my reaction. “The old ones were the best. They hadn’t done it for so long, it was like f***ing a virgin.”

Sometimes she would say, “I wish you would stop doing things that would make society think that you’re evil. You’re not evil.” And sometimes they would just laugh and say “we are evil, proudly.” And sometimes people would ask her, “why are you helping these boys? There are plenty of other people that you could be helping. These are boys who killed people.” And she says there were times that she herself wondered if she was crazy, she says,

“But these young people didn’t know why they’d raped, looted, and killed, or even remembered much of it, they had been so high. They had been exploited, used up, and thrown away. The war had destroyed their childhoods the way it had destroyed mine. The ones I thought deserved our anger were men like Charles Taylor, Prince Johnson, Roosevelt Johnson, and Alhaji Kromah, who had started the war and perpetuated it, letting their selfish ambitions for power ruin the lives of an entire generation.”

The fighting started and stopped, started and stopped, and every time it started it again included the most brutal violence you can imagine. By this time, the year 2000, the country was utterly exhausted. But Charles Taylor was in power in Liberia and he kept engaging with these warlords. Or rather, the war lords kept fighting Taylor. They wanted him out of office and they wanted power in the country. So it kept erupting into this tragic, extensive senseless violence.

…these young people didn’t know why they’d raped, looted, and killed, or even remembered much of it, they had been so high. They had been exploited, used up, and thrown away…

So Leymah at this point, the year 2000, Leymah had joined an organization called the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding, or WANEP, and at one of these conference she had the thought, and she had been reading Gandhi, and she thought “Who is going to be the Liberian Gandhi?” And she had a friend named Thelma who had the idea of creating a peace-building network like WANEP, but specifically for women.

“In October, 2000, the UN Security Council had passed Resolution 1325, which noted that “civilians, particularly women and children, account for the vast majority of those affected by armed conflict,” and acknowledged the need to protect females from gender-based violence and “increase their role in decision-making with regard to conflict prevention and resolution.” But the resolution’s passage didn’t mean that anything substantial had happened.”

And we see this often with UN resolutions on the podcast, where I’ll read this resolution and it’s super inspiring and it’s the world the way we want it to be, but how does that get implemented and enforced? Sometimes it doesn’t, but it’s something aspirational, I guess. But she says, yeah that’s a really nice thought, but “women were left out of the negotiating process.”

So she and her friend started WIPNET, or the Women in Peacebuilding Network. There were women from Sierra Leone, Guinea, Nigeria, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Togo – almost all the sixteen West African nations. They began with a session in which all the women told their own stories. She said there was this incredible energy in those rooms as they shared their stories and then created strategies for bringing an end to the violence. They started by sharing stories because they recognized that they needed a sense of empathy and camaraderie in the group, and they needed to build the women’s self-confidence. And it really worked. They did develop this sisterhood. And they also developed a workbook that helped them recognize themselves as providers for their families, leaders at church, and peace-builders in their communities. Then they started recruiting everywhere they could; at the market, at the church, in their families, in their social networks, bringing women of all different tribes and socio-economic levels and religions into sisterhood with each other. One of my favorite scenes in the movie and the book was when Leymah went back to St. Peter’s Church, where the massacre had happened, and prepared to give a sermon that would mobilize the women in the congregation. She had emerged as a leader in several different peace-building organizations, and was doing a lot of public speaking. And she says that before every speech or sermon she would pray and ask, “God, what message do you want the people to hear?” And I should mention, too, that the passage during the massacre where she said God isn’t gonna help you, that’s another part that I really appreciated about her story. She’s very honest about times that she felt doubt, and didn’t believe in God, and really struggled to have faith, and then times that she had a lot more faith and attributed things to God helping her. She’s very candid about that process. She is a woman of faith but she had a lot of doubt a lot of times. And so she mentions this, but this is a point in her life when she felt God’s hand in a lot of the things that she was doing. And so here is what she says:

“This day, I stood at the front of a full church, men sitting with their hands clasped, women fanning themselves and their babies in the heat. Too many faces were lined with exhaustion and worry. And the words came to me:

“This is a completely terrible life to live,” I said. “We are tired.” “Yes!” women called back. “We are tired. We feel it’s now time to rise up and speak, but we don’t want to do this alone. We want to invite the other Christian churches to come, and let’s put our voices together. You’re asking, who are these women? I will say, they are the ordinary mothers, grandmothers, aunts, sisters. And for us this is just the beginning.” Applause, cheers. I looked to where the WIPNET members all sat together and saw Asatu raising her hand.”

I’ll just interject here, Asatu was their Muslim friend. This was a Muslim woman.

“And she, Asatu, rose from her seat and came to stand before the congregation. “Praise the Lord!” she said. “Amen!” several women cried out. “I have a surprise for this congregation,” she went on. “I’m the only Muslim in the church.” “Hallelujah!” the women said. “Praise the Lord!” “I was moved and impressed by the Christian women’s initiative,” Asatu said. “God is up. We are all serving the same god. This is not only for the Christian women. I want to promise you all today that I am going to move it forward with the Muslim women. We will come up with something, too, and we will all work together to bring peace in Liberia.” It was a stunning moment. Asatu’s hand reaching across a very old divide. Most of Liberia’s Muslims are from the Mandingo tribe, and to a lesser extent also Vai, Gbandi, and Mende. Before the war, before President Doe’s obsession with tribal identity split everyone apart, Christians and Muslims mostly got along. We were neighbors and friends, we intermarried, including in my family. But a lot of non-Muslim Liberians viewed the Mandingos as a group apart. Christian and Muslim women had never worked together, and certainly not for anything political. Asatu was proposing an alliance that no one had imagined before.”

So Asatu did recruit in her network a huge number of Muslim women. And Leymah writes,

“Three days a week for six months, the women of WIPNET went out to meet with the women of Monrovia; we went to the mosques on Friday at noon after prayers, to the markets on Saturday morning, to two churches every Sunday. We always went in pairs; if we set up a table at the market, we always had a two-woman team. (Sometimes, we temporarily paired women who weren’t getting along, so that was their punishment.) We gave all our sisters the same message: Liberian women, awake for peace!”

And she continues by telling how they did this work, recruiting and mobilizing the women all over the country. She’d say, “Hello, sister! I’m Leymah Gbowee from WIPNET and I’d like to tell you about a campaign we just started. This war has been going on a long, long time and all of us have been suffering. People have tried to end it, and there’ve been some big meetings, but we think the answer lies with women. We need to step forward and get involved.” They would say, you know, I don’t really know if this is my business. And Leymah says she would reply, “Why is this your business? You are the one who has been raped by the fighters. Your husband is the one who’s been killed. It is your child being forced into the army.” And the women would say yes, that’s true, we’ve just been sitting here and letting people take our children. And they would work with these women and get them to join the organization. And Leymah says it wasn’t always easy because women who have suffered for nearly as long as they can remember come to a point where they “look down, not ahead,” is the way she phrases it. But she just kept working with these women and recruiting more and more. They would hand out flyers saying “We are tired. We are tired of our children being killed. We are tired of being raped. Women, wake up! You have a voice in the peace process.”

And then she says that they knew that many of the women that they were reaching couldn’t read. So they hired a boy to do colorful drawings that explained the mission so that they could reach everyone. And one drawing showed a woman standing before a group of fighters and talking to them. “Hour after hour,” she says, “we patiently answered questions, and each week we could feel more of an awakening. We worked in a world inhabited by women and we used women’s networks to communicate. When the market-women bought fruits and vegetables from women in rural areas, they passed along our message. And when they sold their goods in the city, they shared it with the women who were their customers. We worked quietly. No news organizations noticed what we were doing or reported on our efforts and we liked it that way. We were laying a foundation, though for what we didn’t yet know. While the outreach campaign ran, the Christian women continued meeting to pray, and Asatu continued to organize her Muslim sisters. But bringing the two groups together was turning out to be difficult. The new rebel group, LURD, was predominantly Muslim, and there were muttered comments that Muslims were the ones responsible for prolonging the war. Some of the Christian women felt that praying with the Muslims would dilute their faith. They pointed to the Bible, to 2 Corinthians, that says “Do not be bound together with unbelievers, for what partnership has righteousness and lawlessness, or what fellowship has light with darkness?” And so we ran a new workshop, and together the Christian and Muslim women did the exercise Being a Woman. “Write your titles on this sheet of paper,” I told the assembled group when we were put together in one room. “Lawyer, doctor, mother, market-woman. Put them in this box.” I held up a small carton. “See? I’m locking them away. We are not lawyers, activists, or wives here. We are not Christians or Muslims, we are not Kpelle, Loma, Krahn, or Mandingo. We are not indigenous or elite. We are only women.”

And she continued by asking, “Does the bullet know Christian from Muslim? Does the bullet pick and choose?” By the end of the workshop, the women came to an agreement that the Christian and Muslim women would each have their own leadership but that they would work together.”

So she says that in December of 2002, they had their first public demonstration where 200 women, with Christians in their lappas – which is their traditional dress – and then alternating with Muslims with their headscarves, and they marched through the street singing a Christian hymn and a Muslim song and then a hymn again and then a Muslim song. And she says that crowds just turned to stare. This time they had notified the press, and the press was waiting for them and publicized this event. And their message was, they said, “We envision peace. A peaceful coexistence that fosters equality, collective ownership, and full participation of particularly women in all decision-making processes for conflict prevention, promotion of human security, and socio-economic development.”

So at this time, she says that Liberia had been ravaged by thirteen years of war, and they couldn’t imagine that there could ever be anything more terrible than what had already happened to them. But they said that what they didn’t know was that the worst was about to come. In 2003, yet another rebel group had split off from another one and begun capturing towns and villages in the southeast. She says,

“A new wave of violence swept through that part of the countryside, killing, looting, raping. Tens of thousands of men and women, with children on their backs and everything they owned in bundles on their heads, poured down rural roads into the brutal poverty of the Internally Displaced Persons camps near the capital or the city itself. In some areas, entire counties emptied and gunmen looted the deserted towns.”

All of these rebel groups were fighting to get Charles Taylor out of power, and meanwhile the country was just suffering. By now, 360,000 people had been driven from their homes and were living in the foul tents of twelve camps in five counties and scattered across five foreign countries. And the fighting went on, growing closer and closer to the capital. So they knew they had to do something, so the women of WIPNET got together. And I love how she described this because she says, like, “okay we need to do something, let’s go out onto the streets and put pressure on the government. Who’s got markers?” It’s just like regular people trying to figure out what to do, and it’s like this larger than life, huge problem, and they just are not backing down. “Who’s got markers? Who’s got posters?” They just wrote out slogans on posters and decided to do a mass sit-in. They also decided to make a public statement. And they scheduled a gathering at City Hall for April 11th, I believe this is 2003. President Taylor had been street marches, and said nobody would get into the street to embarrass my administration. And she said we were gonna assemble anyway. They knew that they were risking their lives. But they had a radio station, one of the women had access to a radio frequency, I guess, and they sent out word and said “if you want peace, make it your duty to come to the Monrovia City Hall at 8am. Wear white.” And they also sent three separate invitations to Charles Taylor that he show up too. And they said, “We have a statement to present to you.” And now I’ll quote from the book:

“The morning of the 11th, the steps of city hall were a sea of white. There were hundreds of women there, maybe as many as a thousand. Some of the city’s religious leaders turned out as well. Taylor supporters and soldiers mixed through the crowd, and local media was everywhere. Emotion ran high as women stood to testify what the war had done to their lives. And I got a little afraid that WIPNET would lose control of the gathering.”

But she said to the group, “In the past we were silent,” I told the crowd. “But after being killed, raped, dehumanized and infected with diseases and watching our children and families destroyed, war has taught us that the future lies in saying no to violence, and yes to peace. We will not relent until peace prevails.” The women erupted, “Peace, peace!”

And they later learned that Charles Taylor had told the soldiers to flog them if they marched in the streets, but luckily that didn’t happen. They gave President Taylor three days to respond to their demands, and if there was no answer in that time then they would stage a sit-in. And Taylor didn’t respond and so they moved ahead. And so what they did was they tried to reach every woman they possibly could to meet near the fish market in Monrovia.

She says, “On the morning of April 14th, I woke before dawn and made my way in the dark. I was the first one there. As the sky got lighter, I looked around anxiously. For the protest to succeed, we need at least a few hundred women. Finally, one group arrived. Then another. The sun rose. And then I heard the sound of diesel engines, and up the road toward me came a line of buses. Mixed in were trucks. Trucks full of women. There were a hundred on the field. Three hundred, five hundred, a thousand. I started to cry and to pray. The women kept coming. Fifteen hundred. We asked where they were from and learned that some government agencies had taken the day off. NGOs with women’s programs had required their staff to join us. University students and female professors were there. More than 2,000 women were on the field now. Market women, displaced women from the camps. Some of them had been walking for hours and wore clothing so old it barely looked white. One woman had used a curtain for her hair tie because she didn’t have anything else. WIPNET workers handed out t-shirts and placards and gathered the women to sit for peace. After a while we got word that Charles Taylor had left his home and would be driving by. It was the hour when anyone on the road was expected to turn away or risk being shot. No one actively made the decision, but the women rose, walked to the roadside, and faced the president’s convoy, holding a huge banner. “The women of Liberia want peace now.”

So, incredibly, President Taylor finally did respond after this massive sit-in. And he said okay fine, come to the mansion and you can give your speech. So you can even just look it up on YouTube. You can of course watch it in the film, but there’s footage, there’s a video of Leymah Gbowee addressing Charles Taylor. And they said that they had arranged the microphone so that Taylor would be behind her and she would be speaking to the crowd, and she turned her body on purpose so that she could speak– she was actually speaking to a woman that worked for Charles Taylor and kind of shaming her, like you’re a woman, you should be doing something about this. So she spoke to the woman and then said “please deliver this message to Charles Taylor.” And you can watch this footage of Leymah Gbowee demanding peace on behalf of the women of Liberia. It’s so powerful to watch it and to hear her voice.

Because of all of this pressure, and honestly the embarrassment because all of these events are being covered in international news and so he’s having his pride threatened, Taylor agrees to arrange a meeting with the war lords to try to negotiate peace. But the fighting didn’t stop, so the women met at the market day after day after day, in 100 degree weather, in pouring rain, always wearing white, and holding up signs. And check out the website and Instagram for pictures of these demonstrations, but it really is neat to see the footage and to hear them singing together. And you can hear that in the movie, “Pray the Devil Back to Hell!”

And there was another aspect to their activism. So you may remember part of the subtitle, “How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War.” If people do know something about the Liberian Civil War, it’s usually the sex part. It’s usually oh, that’s the war protest where the women staged a sex strike. Like the Greek play by Aristophanes, called Lysistrata. I’ve heard several people say, “oh yeah that was like Lysistrata with the sex strike.” And it is kind of like that, I guess, but here’s how Leymah tells it:

“What does it take to make those who fight listen to reason? What haven’t we tried? One day, when Asatu was talking to a journalist, she joked “maybe it will just get to the point where we deny men sex.” Everyone laughed, but it was something to think about. As a woman, you have the power to deny a man something he wants until the other men stop what they are doing. We announced on the radio that because men were involved in the fighting and women weren’t, we were encouraging women to withhold sex as a way to persuade their partners to end the war. The message was that, while the fighting continued no one was innocent. Not doing anything to stop it made you guilty. The women protesting in rural communities were more organized in their sex strike than those of us in Monrovia. They already had set aside a separate space where they sat each day and the men couldn’t come. They made their refusal religious, saying they wouldn’t have sex until we saw God’s face for peace. Bringing God into it made their men fearful of opposing them. In the capital, some of the women gave in. Some came back to the field with bruises, saying their husband hit them when they said no. The strike lasted on and off for a few months. It had little or no practical effect, but it was extremely valuable in getting us media attention. Until today, nearly ten years later, whenever I talk about the Mass Action, “what about the sex strike?” is the first question everyone asks.”

So it was an important part of the strategy, but mostly just to gather media attention. We’ll go back to these sit-ins that were happening in Monrovia by the fish market. And back to the religious aspect of the demonstrations too, she talks about how “Monrovia’s bishops and imams stood at the edges of the fish market” supporting them. And this was a big field, it wasn’t necessarily the market, it was a big field kind of adjacent to the market. And she says, “The men in our lives, our families, offered their help. …The Mass Action for Peace got most of its funding from churches, but often ordinary men and women, even soldiers and government workers, stopped at the field and offered us food or money. ‘Thank you, mothers,’ they said. ‘Our future depends on you.” And then Leymah lists many other donors, including The Global Fund For Women! And that was so cool for me to read, I was just re-reading the book preparing for this episode– I’d read it a few years ago and at that point I didn’t know Anne Firth Murray. But the Global Fund for Women is the one that was started by my professor, Anne Firth Murray, who spoke on our episode just a couple of weeks ago! So that was so cool for me to read.

Finally, back to the story, Taylor and the warlords agreed to peace talks. After all of these sit-ins and pressure from the women, thousands of people doing this sit-in by the fish market. So Taylor and a bunch of the warlords flew to Ghana. And some international peacekeepers flew there too to oversee the negotiations. And they checked into a hotel to have those meetings together, but soon after Taylor arrived, surprisingly – kind of shockingly to everyone – he was indicted by a war crimes tribunal conducted by the UN and Sierra Leone for his involvement in crimes against humanity in the civil war in Sierra Leone (which he had, in fact, committed but it didn’t have as much to do with Liberia). So he was about to be taken in for a trial, so he fled from Ghana, he went back to Liberia. And she says that there, Taylor’s boys “roared through the streets in jeeps. If the president was arrested, they vowed, “We will kill everyone and burn everything. Liberia will cease to exist.” The forces against Taylor also were trying to seize their opportunity to get Taylor, and they stormed into displaced persons camps, sending 100,000 refugees who had already been displaced by the war back into the streets in torrential rain. The country was plunged back into conflict.

Meanwhile, Leymah and 300 other Liberian women who were working for peace had gone to Ghana to be there for the peace negotiations. And she said that they kind of staged a sit-in outside the hotel where the warlords were supposedly negotiating. Taylor wasn’t there – he was back in Monrovia, and this is a side note but important: he signed a cease-fire agreement and said he would step down. The UN announced it and said they would lend support and troops and there was dancing in the streets, and the women in Ghana heard about it and celebrated… But then Taylor went back on his promise to leave office, the cease-fire fell apart, and the anti-Taylor forces launched three separate attacks against Monrovia so horrific they came to be known as World Wars I, II, and III. Again there was a frenzy of killing, and raping, and fighting in the streets. Days of bombardment left more city blocks burned, and pavement strewn with rubble, and trash everywhere. She says, “Every house, every store, was looted and smashed. People ran on carpets of shell casings and carried their wounded by wheelbarrow or on their backs, desperately trying to reach the makeshift clinics operated by international volunteers. Not a single public hospital was open anywhere in the country.”

The women who were in Ghana trying to help the men negotiate peace, were meanwhile hearing about their family members stuck in this horrible spate of violence in Monrovia. So you can imagine how terrifying that was. Leymah says the women would call home to talk to their families and hear gunshots in the background of the phone call. One of the women talked to her teenage son and he said, “Mom, I helped dig a mass grave today.” And she said all they could do was sit and cry and cry.

In the meantime, the leaders who had gathered for peace talks were trying to figure out how to leverage the situation for personal gain. One warlord said he wouldn’t stop fighting unless he was guaranteed a lucrative job afterward. Another leader said it didn’t matter what happened – they would kill everyone in Monrovia, then go back to their own women and replenish the population. Even those of the leaders who weren’t so horrible were sitting around in a fancy hotel having drinks and talking about sports and girls. And Leymah said the women would just observe them, on vacation swimming in the pool, with the international community paying for it all. And so it dawned on Leymah and the other women, as they sat on the sidewalk at the hotel day after day while the men partied inside, that these men did not want to end the war. The war was where they got their power. And finally she snapped. She writes:

“I knew what I had to do. The negotiating hall was full that day, with representatives from all of the different warlords and different factions, and Taylor, as well as Liberian political parties and civil society groups. It was time for their lunch break. I led our women into the hallway, then dropped down in front of the glass door that was the main entrance to the meeting room. “We are sitting right here.” More women came, then more, until there were 200 of us and the hall grew hot and crowded with a sea of white t-shirts and black lettered signs: “Butchers and murderers of the Liberian people, stop.” “Sit at this door and loop arms,” I instructed them. “No one will come out of this place until a peace agreement is signed.” I tapped on the glass, and when the door opened I handed a note to a man inside. “Please give this to General Abu Bakr.” [That was the man who was in charge of the peace negotiations.] I saw the general read the piece of paper. It said “We are holding these delegates, especially the Liberians, hostage. They will feel the pain of what our people are feeling at home.”

So they had people come out to the hall and say, “this isn’t legitimate, you can’t do this, who’s the leader of this group? You have to leave the hall, you have to let the people out for lunch…” And the women just sat there. And again when they asked for the leader of the group she said:

“I’m right here,” I said, rising to my feet. “You are obstructing justice and we are going to have to arrest you.” Behind me, the door to the negotiating room opened and men’s faces peered out. Obstructing justice? Had he really just said that to me? Justice? I was so angry I was out of my mind. “I will make it very easy for you to arrest me. I’m going to strip naked.” I took off my hair tie. Beside me, Sugars [another leader in the group] rose to her feet and began to do the same. I pulled off my lappa, exposing the tights I wore underneath. “No, no!” Shouted the husband of one of our protestors, a Liberian banker who had come to the talks that day. I didn’t have a plan when I started taking off my clothes. My thoughts were a jumble. “Okay, if you think you’ll humiliate me with an arrest, watch me humiliate myself more than you could have dreamed.” I was beside myself, desperate. Every institution that I’d been taught was there to protect the people had proved evil and corrupt. Everything I valued had collapsed. These negotiations had been my last hope but they were crashing too. But, in threatening to strip, I had summoned up a traditional power. In Africa, it’s a terrible curse to see a married or elderly woman deliberately bare herself. If a mother is really upset with a child, she might take out her breast and slap it, and he’s cursed. For this group of men to see a woman naked would be almost like a death sentence. Men are born through women’s vaginas, and it’s as if by exposing ourselves, we say “we can take back the life we gave you.” Fear passed through the hall.”

No one will come out of this place until a peace agreement is signed.

And I just love this part. I mean, it’s a completely different cultural norm, so I had no idea what that would even mean for her to take off her clothes. But I love that she invokes this common belief and fear, and it actually has an impact on the men. So the men start saying “no, no, no, don’t do that, please don’t take your clothes off. We’ll listen to you.” And the women say, “okay, we are gonna sit her. You are gonna be in that room without water and food, just like our people back home in Liberia are without water and food. So you can feel what they’re feeling just a little bit.” And so they called the press, they came over and covered this sit-in, and she says, “Here is what we want: the peace talk has to move on. All of these men will attend sessions regularly. They have to pass by us and don’t ever insult us, because we are not crazy. What we’ve done today is send out a signal to the world that we, the Liberian women in Ghana at this conference, are fed up with the war. And we are doing this to tell the world we are tired of the killing of our people. We will do it again.”

The next part of this story is that, she says, “The Liberian War didn’t end on the July day we blocked the hall in Accra. On August 4th, West African Peacekeeping Troops arrived in Liberia to crowds that lined the streets, weeping and cheering. On the 7th, Nigerian Peacekeeping Troops intercepted ten tons of AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenades bound for Taylor at the Monrovia airport. If the weapons had gotten through, the president might well have continued to fight. But what we did marked the beginning of the end. The atmosphere at the peace talks changed from circus-like to somber. The talks proceeded without further delay. On August 11th, Charles Taylor resigned the presidency and agreed to go into exile in Nigeria. When we returned to Liberia, a crowd of women came to meet us at the airport. They wore their WIPNET t-shirts and were singing. Sugars and I looked at each other and laughed. Everyone nodded at us, touched us, smiled at us as we passed through security. “These are the peace women. These are the women who did great work. Thank you mothers, thank you.”

As beautiful as that is, and as much of a beautiful ending to the story as that is, there’s still just a little bit more. She says, “A war of fourteen years doesn’t just go away. In the moments we were calm enough to look around, we had to confront the magnitude of what had happened to Liberia. 250,000 people were dead. A quarter of them children. One in three were displaced, with 350,000 living in Internally Displaced Persons camps and the rest anywhere they could find shelter. One million people, most of them women and children, were at risk of malnutrition, diarrhea, measles, and cholera because of contamination in the wells. More than 75% of the country’s physical infrastructure, our roads, hospitals, and schools had been destroyed. The psychic damage was also unimaginable. A whole generation of young men had no idea who they were without a gun in their hands. Several generations of women were widowed, had been raped, seen their daughters and mothers raped, and their children kill and be killed. Neighbors had turned against neighbors, young people had lost hope, and old people, everything they’d painstakingly earned. We were traumatized. We had survived the war but now we had to try to remember how to live.”

This began the post-war period, and Leymah was still leading peace-building efforts and reconciliation efforts after the war was over. She says, “We had to ensure that what we had done had a lasting impact. We had shown women’s awesome power, but to me our actions were the foundation of a movement, not its end product.” So one of the things they did was sign a declaration emphasizing the importance of involving women in every aspect of the peace process. And back in Monrovia they held a three-day conference that helped break down the bureaucratic language of the peace agreement into information that any ordinary woman could understand. This is what the agreement promises… This is how and when you should see certain things happen in your community… This is what to do and where to go if you don’t see those things happen. And then they worked with UNICEF on a campaign to encourage kids, especially former fighters to go back to school. And then one of the really interesting parts that I would not have thought of was disarmament. And the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) was in charge of taking the guns. The country had been flooded with weapons, and they needed to get them out of the hands of these teenagers in the country. And so the UN showed up, and said “don’t worry, this is gonna go fine, we’re bringing in experts that have experience from Kosovo.” And the plan was essentially to offer money for guns. So just show up to this place, bring your AK-47s, your machine guns, your machetes, bring all these weapons and show up to this place and then we’ll pay you for these guns. So the women hear this plan of the UN and they’re like “oh, that is not gonna work. That is not gonna go well.” And so they show up, and the leaflets that the UN had given to people showing pictures of cash, of course attracted a ton of people. It attracted more than 3,000 heavily armed former fighters. Most of them Taylor’s troops. Leymah writes, “There wasn’t enough food, water, or money to go around. And after the men had stood in line for hours in the hot sun, they started drinking and smoking weed. Suddenly, that familiar terrible sound, pop pop pop. The line broke down, bullets were flying, and people were running. It was total chaos. Rioting, looting. The UN staff fled, leaving locals to clean up the mess.”

After that, she says that she and Sugars, a friend and leader, she says they approached two of Taylor’s former generals and offered their help. “We know how to work with these boys,” we told them. And so they organized an event, and again they brought these women who had come to be thought of as the mothers of Liberia. They went to the events where the boys were supposed to trade in their guns and their weapons for money, but tons of women showed up. And this wasn’t mentioned in the book but it was one of the most moving parts of the film, I think it’s just somebody’s cell phone camera panning the crowd, and there’s this woman holding a sign that says “Lay down your weapons. We love you.” And it’s so, so moving to me. Just the presence of these women saying, “we know these boys, we know these people, these are members of our community.” And they have to feel a sense that they’re still good human beings and that there’s a path forward for them without their weapons.

And the last thing I wanna share from this story is the election after Charles Taylor was ousted. In November, 2006, Liberia elected the first woman president on the African continent, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Sirleaf was a Liberian-born, Harvard-educated politician who had run against Charles Taylor (and lost) years before, and had been in dire danger during all the wars. But she was elected and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011, and served as Liberia’s president from 2006-2018. And I’m sorry, but I do have to throw in here that if you watched the show Parks and Rec with Amy Pohler, do you remember the character Donna? She’s played by an actress whose professional name is Retta, but her full name is Marietta Sirleaf, and she is the niece of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Which I’m sorry, but maybe it’s the only comic relief of the episode and there it was, right at the end. When I learned that, I thought that was just a great bit of trivia.

But it’s so inspiring that in Liberia, where this violent, malevolent patriarchal culture had really had such a hold over the country, that it was a group of women who ended the war, turned the tide, and then elected a woman as the president. And that is the story of the heroic courage of Liberian women, who used partnership to fight violent dominators… and won. I hope you have been as inspired as I have been by these women, and my hope is that the more people will know this story, and that we can learn and implement these lessons in all kinds of situations.

Butchers and murderers of the Liberian people

stop.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!