“this is a world which is oppressing people in ways that are severe and systemic and interconnected”

Amy is joined by philosopher and author Kate Manne to discuss her latest book, Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia, and dig deep into issues of body image, weight shaming, correlation v. causation, and how to create a more just society for people of all sizes.

Our Guest

Kate Manne

Kate Manne is an associate professor at the Sage School of Philosophy at Cornell University, where she’s been teaching since 2013. Before that, Manne was a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows from 2011 to 2013, and she did her graduate work in philosophy at MIT from 2006 to 2011. And before that, she was an undergrad at the University of Melbourne where she studied philosophy, logic, and computer science.

Today, Manne does moral philosophy, especially metaethics and moral psychology, feminist philosophy, and social philosophy. She also enjoys writing opinion pieces, essays, and reviews for a wider audience. She has published multiple highly acclaimed and widely read books, including Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny in 2017, Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women in 2020, and Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Among all of the topics that I’ve covered on episodes of this podcast, some have resonated with certain groups of listeners, others have only been relevant to other groups, but one topic is relatable to every single human being: the fact that we live in our bodies, so succinctly summed up in the 1970s landmark text Our Bodies, Ourselves. It was with this in mind that I started reading Kate Manne’s book, Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia, which was released in January, 2023.

Over the course of the few days that I was reading this book, I noticed that the topic of fat bodies came up in multiple conversations and several media articles into my inbox. Everyone with an opinion and everyone full of concern, primarily about the medical implications of fatness. So I was very struck by a passage in the book on shrinking, where after debunking several of the very medical beliefs that I was encountering, Manne writes, “Even if fat people are subject to greater health risks purely on account of our fatness, how much does this matter practically and to the public discourse swirling around our bodies? We still deserve support, compassion, and adequate health care. We still deserve to be treated like human beings.”

This struck my heart powerfully, and I am so excited to discuss this topic today with legendary feminist philosopher, Kate Manne. Welcome, Kate! We’re so excited to hear from you today.

Kate Manne: Thanks so much for having me, Amy!

AA: We’ll start with your professional bio first and then I’ll have you introduce yourself more personally in a minute. Kate Manne is an associate professor at the Sage School of Philosophy at Cornell University, where she’s been teaching since 2013. Before that, she was a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows from 2011 to 2013, and she did her graduate work in philosophy at MIT from 2006 to 2011. And before that, she was an undergrad at the University of Melbourne where she studied philosophy, logic, and computer science.

Now, Kate does moral philosophy, especially metaethics and moral psychology, feminist philosophy, and social philosophy. She also enjoys writing opinion pieces, essays, and reviews for a wider audience. She has published multiple highly acclaimed and widely read books, including Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny in 2017, Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women in 2020, and Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia, which is the book we’ll be discussing today.

I can’t recommend these books highly enough to listeners, all three of these books that I just listed. And again, I’m so honored and excited to have you here, Kate. I wonder if you can start us off by telling us a bit more about you personally. Where you’re from and your experiences that led you to write each of your books, and especially the book that just came out this week, right? I just got my copy in the mail.

KM: Yes, just a week ago.

AA: So tell us about yourself.

KM: Yes, I’d love to. I am an Australian author and philosopher. I grew up about an hour outside of Melbourne and I’m often asked, because I have written two books on misogyny, and in those books I argued that misogyny is something girls and women face rather than something that men feel deep in their hearts. But when I wrote those two books on misogyny, I was often asked how I first got interested in the subject. And I found that I really couldn’t tell that story without telling a story about fatphobia and its intersection with misogyny.

I was one of three girls at a hitherto all boys school the year it integrated in the outskirts of Melbourne. And I faced a lot of misogyny during those two final years of high school, where I was bullied and belittled for my then merely somewhat fat body, I would say I was a merely chubby teen. But nevertheless, the form that misogyny often took was bullying and belittling for my size. So that really is the origin story for my interest in misogyny and also my interest in fatphobia as a social system that oppresses so many of us and has particularly pointy intersections with misogyny, racism, classism, ableism, transphobia, and more.

AA: Hmm, okay. Well, that’s a perfect bridge to dive into the book itself, because one of the things that really struck me was right as I started the book in the introduction, you were so vulnerable. You wrote really personally and I found that to be incredibly courageous. And I wanted to ask you about that introduction and your choice throughout the book to talk about your personal experiences rather than just with some academic remove and talk about it more philosophically.

KM: Thank you, Amy. I really appreciate the kindness. It was a decision partly because I feel like I’ve been mired in shame since those early experiences, really. And because of that shame, which is a really natural result of being shamed, of having disgust directed at your body. I won’t get too deep into it, but I had things like “fat bitch” scrawled on my locker, which was also doused in fish oil. I was voted the person most likely to have to pay for sex at the high school leavers last assembly. It was really humiliating. And I think that the subsequent experience of shame has this really characteristic set of effects on people, bodily. So think about the characteristic expression of shame in head bowed, eyes lowered, wanting to disappear, breaking the sight line between yourself and other people. And so, instead of being mired in that shame, this book is really an exercise in trying to lift my head up, meet the reader’s gaze, and find solidarity and community in not being shamefaced about those experiences that are so not unique to me. That so many of us have had experiences of feeling ashamed of our bodies in various ways, various reasons, and that I think invite the possibility of community and connection. And one can really only do that by being vulnerable and saying, “this is my story, me too,” to invoke the name of Tarana Burke’s amazing movement that she’s been leading for well over a decade now. #MeToo is an invitation to relate to those stories and to find solidarity rather than shame as a basis for collective political action.

AA: I’ll just say again, as a reader, too, I noticed that when I finished the book I had so many takeaways and many of them were philosophical and logical arguments and data based. But I’m thinking like, when I think about this book five or ten years from now, and I’ll probably read it again too, but the most powerful takeaways sometimes are actually the empathy pieces like stories. And there were certain stories that you told that are making me emotional to think about, but that really, really impacted me emotionally. And I’m just thinking of people who haven’t done that mental exercise of empathy, of thinking about what it feels like for someone, like the bullies who wrote that horrible thing on your locker. I mean, my hope and wish is that everyone would read it. Those who struggle with the internalized shame, but also those who shame others. That could be world-changing because to take a step into somebody else’s lived experience is sometimes the most powerful thing of all. So I’m grateful that you included that.

KM: Thank you so much. That means a lot.

AA: So to start off, let’s talk about the term “fatphobia” itself. Why did you choose that term? And I’ll say here that just by coincidence I discovered another activist in this field as I was reading your book, and she said that she personally doesn’t use the term fatphobia. So I thought I’d give you an opportunity to talk about the choice of that word and what it means to different people.

KM: Yes, totally. So the terms “fatphobia” and “anti-fatness” I use synonymously, and I like both of those terms. One potential problem with the term fatphobia that some brilliant people in this space have pointed to, I think it was Aubrey Gordon, is that they could potentially sound like they’re individual forms of fear and loathing or hatred, almost like agoraphobia or arachnophobia. But I think the phobia parallel with forms of oppression that are really well recognized among left-wing and liberal people like transphobia and homophobia is the parallel that will be salient to many readers. So I tend to think that fatphobia is useful in establishing those parallels with broad systems of social oppression that we’re perhaps somewhat more accustomed to thinking about critically and viewing ourselves as having a role in fighting them. So that’s one reason I like the term fatphobia because I actually think that it does highlight these parallels. And I have a slight worry that “anti-fat bias” can itself sound a little bit individualistic because bias is often thought of as something that is psychological and in people’s heads.

so many of us have had experiences of feeling ashamed of our bodies in various ways, various reasons, and that I think invite the possibility of community and connection

But there’ll never be a perfect term for any of these things. In the end, we just have to think about them in a way that is healthier and more productive and generative and fruitful. So I think that people working in the space, we’re generally on the same side of thinking of these as big structural forms of oppression rather than mere forms of interpersonal hostility that could be combated just by changing people’s attitudes. We certainly do need to change attitudes, but we also need to change the world and the social structures that oftentimes fat people are facing in navigating a world that is actively hostile to us and our bodies.

AA: Yeah, that was a big takeaway that I had. So as long as we’re talking about terminology, I know in the book it was really useful for me to read your discussion about the term “fat people” and talking about reclaiming the word “fat”. Could you talk about that?

KM: Yes, absolutely. So I know that the word “fat” can be uncomfortable for many people who view it as a shaming term, but like many people who are working in this body liberation or fat activist tradition, I’m someone who thinks that we can reclaim the term and use it as a merely neutral description of some bodies, much like short or tall, or for that matter, thin. We should use all these terms neutrally just to describe a way somebody’s happened to be without any shame or judgment or anything negative attached to it. So I prefer the term fat, which is matter of fact in that way, to terms like “curvy” or euphemisms like “husky” or “fluffy” or anything like that feels a bit like dancing around the point. There’s something quite healing in just being able to name fat bodies as such.

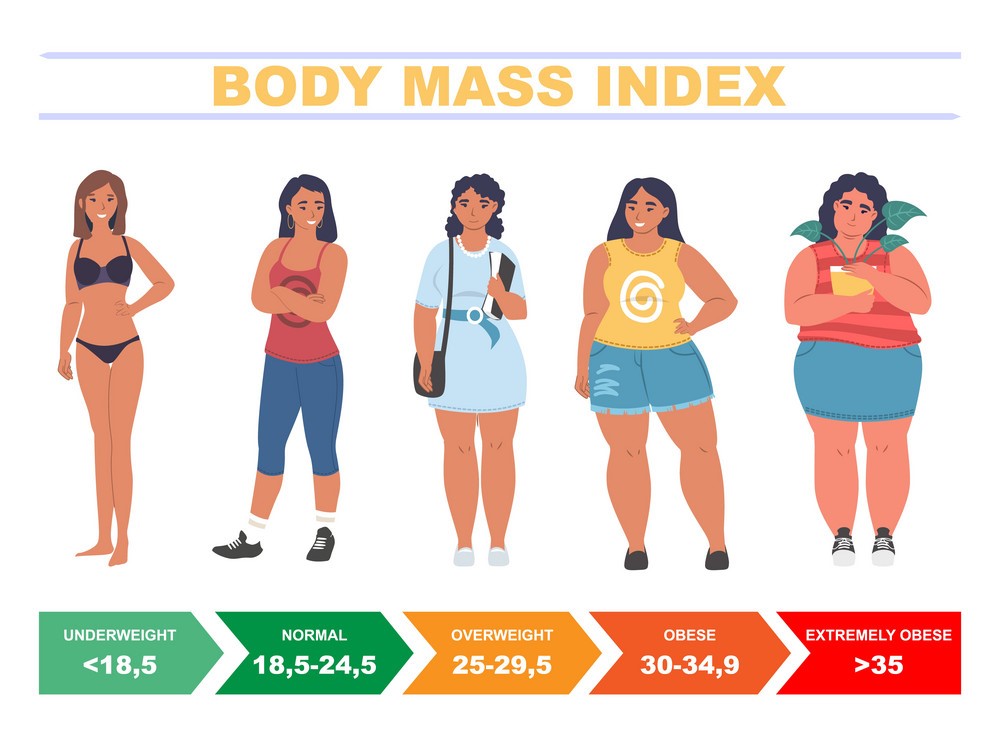

And I’m also against medicalizing stigmatizing terminology, like overweight or obese. I do use those terms in the book when I’m discussing medical studies that use those categories from the notoriously problematic BMI charts that have a long and storied history and that are really inaccurate in lots of ways, very reductive. But those terms really imply there’s something wrong with having more flesh, and the science on this often belies that point. It turns out that people in the “overweight” category have the lowest mortality risks, statistically speaking. So it raises the question, over what weight? So those terms to me are not more accurate, they’re actually full of stigmatizing and inaccurate connotations that we should distance ourselves from.

AA: Yeah, you talk in the book about how, I mean, I think I’ve been guilty of this too when a little child, I have four kids, and if a little child will point to someone and say, “Oh mom, she’s so fat” or “he’s so fat” or something. And you’ll hear the mom say, “Oh honey, don’t say that.” Or if they say it about themselves, like “Am I fat?” Like, “No, no, no. Don’t say that about yourself.” It’s instantly stigmatizing to whoever you’re thinking about and it gives the child the message that it’s bad, that there’s something wrong with it, right?

KM: Yes. It’s such an understandable instinct as a parent, and I have had moments of having to restrain that impulse in myself, but ultimately it’s much better in these ongoing conversations, which a brilliant book on this topic, by the way, is my friend Virginia Sole-Smith’s book, Fat Talk: Parenting in an Age of Diet Culture, which emphasizes that we can talk about fatness as not a bad word, as not something to be avoided. Of course, it’s a little tricky if a child comments on someone else’s body and they might not be comfortable with the term fat, but then the message can be, “Oh, we don’t comment on people’s bodies or what they look like.” But to emphasize in other discussions there’s no contrast between being fat and being smart, being beautiful, being successful. Fat people are really cool and do all sorts of cool and awesome things. And why wouldn’t you want to be like an Aubrey Gordon or a Virginia Sole-Smith, or any number of fat people who you can hold up as examples of fabulous people living their lives, doing cool things who happen to be in larger bodies?

So yeah, I’ve become someone who in those conversations, we’ll talk about my fat tummy in a way that’s really unapologetic and it has this nice effect where my daughter will now call me her “squishy little mommy.”

AA: Haha, I love it.

KM: Which I think is actually beautiful and really accurate. I’m a petite fat person, I’m only 5’2” and I’m a small fat person as well, but I’m very squishy. I am someone who identifies as “small fat”. For those listeners who haven’t heard this terminology, it’s useful oftentimes to distinguish between people who are at different points in the fat spectrum. So “small fat,” “mid fat,” and “large fat” people, because it’s good for someone like me to own the fact that I have a certain amount of privilege as a “small fat” person. But yeah, not using euphemisms or making children afraid of fatness, but rather thinking that fatness is compatible with every wonderful way of being in the world. I think that is where I have come to think is perhaps the healthiest way to approach these admittedly fraught conversations.

AA: Fabulous. Thank you, Kate. You talked a minute ago about structures that exist in our world that create really difficult situations for fat people as they navigate the world. Can you talk about some common difficulties that fat people face?

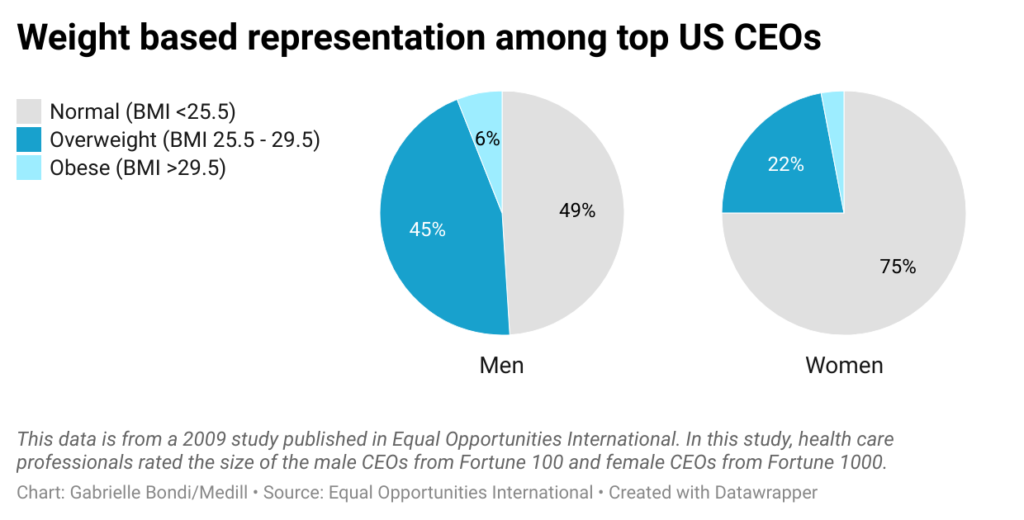

KM: Yes, absolutely. So one piece of it is what starts very early on for fat children, which is schoolyard bullying. It seems like weight is probably the commonest basis for schoolyard bullying, which is really distressing. And fat pupils also face negative stereotypes from their teachers. Children are categorized as less able academically and less physically capable in PE classes and so on as they gain weight. So their objective test scores don’t change, and yet teachers classify them as less competent when they’re in larger bodies. So that is a form of discrimination that desperately needs to change. And it’s really systemic. It’s something where we see this affecting people at all stages through their lifespans. It dogs people in education and then we find that some studies from the nineties, which I would be very interested to see replicated today, show that parents are even less willing to support their fat daughters specifically to attend college, which is really heartbreaking.

And then we see this affects people hugely in the workplace, where if you look at employees’ hiring practices, they are much less likely to hire someone who is seen as “overweight” or “obese.” And this is, again, particularly true for fat women. One particularly revealing study showed that if you compared a fat woman, a thin woman, a fat man, and a thin man for a range of employment opportunities from everything from a lecturer to a business person to a manual laborer to an administrator, people pick the thin man as the most plausible competent employee for each and every job opening and the fat woman as the least promising candidate for each and every job opening. So this is really rife because, spoiler alert, there was no difference between their CVs, they were just rotated between the participants so that people got the same information about these four potential employees on average. So we see that this kind of hiring practice is hugely discriminatory in real world scenarios too, and that there are massive wage disparities, particularly which affect fat women. For a very fat woman versus a very thin woman, there is an annual average wage gap for millennials in these categories of $40,000 annually. It’s like a whole salary’s worth of difference between the very fat and the very thin women. So this is costing people economic opportunity, it’s costing people wages accumulating over their lifetime.

And then, crucially, it’s also costing people adequate health care. So this is one of the biggest pieces of fatphobia that is structural and urgently needs combating. Fat patients are subject to numerous pernicious stereotypes about our being lazy, slovenly, noncompliant, weak-willed. Doctors and nurses will say these things quite explicitly and make really stigmatizing assumptions about our exercise and eating habits. There was one study that really stuck with me when I was doing the research on this book, which showed that physicians will explicitly tick the box that says for a fat patient, “This patient is more likely to annoy me. This patient will seem like a waste of my time, and I have less desire to help this patient.” So this isn’t implicit bias, this is really explicit stuff. In one older study, about one quarter of nurses said that they were repulsed by fat patients and didn’t want to touch us. So people are getting really terrible medical care resulting in the fact that many fat people go to the doctor, the doctor doesn’t see past our fatness, and our real problems go undiagnosed.

And so I recount stories in the book of fat people who had really serious forms of cancer and were not diagnosed until it was nearly too late, or too late in some cases, for them to receive adequate treatment. And this isn’t mere anecdata either. We see this show up in the fact that fat patients are 1.65 times more likely to have serious undiagnosed medical conditions upon autopsy. Things like lung carcinoma and endocarditis, meaning that these undiagnosed conditions could have been what killed them, and yet they weren’t able to get adequate medical care in their lifetime. Or as other studies show, they may have avoided medical care because of the expectation of being weight shamed and stigmatized at their doctor. So we also have studies showing, again for fat women, fat people avoid medical care as they get heavier. So this is a world which is oppressing people in ways that are severe and systemic and interconnected.

AA: This reminds me of a passage in the book where you quote Rebecca Pearl, and I wrote this down so I hope it’s okay that I quote her.

KM: Yes, please.

AA: She says: “There’s a common misconception that stigma might help motivate individuals with obesity to lose weight and improve their health. We are finding that it has quite the opposite effect.”

That’s the end of the quote, but like you said in the book, you talk about how the stress of stigma itself increases inflammation and cortisol levels, which are associated with negative health outcomes. And then, like you said, the stigma and shame keep people from going to the doctor. This was really thought provoking for me as I’ve thought back to my own, like taking my kids to the doctor through their lifetimes and their weight has fluctuated a lot, I think all of them. Mine did too, my husband’s did too. And it does feel like almost a phobia from the doctors of like, “Oh, they’re getting up there on the chart. Do you want me to talk to them?” And me being like, “No, that’s going to make everything worse! I’m not worried, my kid isn’t worried. Nothing’s changed about their life. Why do you seem so freaked out that the percentile changes?”

KM: Absolutely.

AA: So, that’s so interesting. But I’d never considered that that might be systemic throughout the entire medical field, that doctors are so trained this way.

KM: It really is. And I think you’ve pointed to a crucial piece of it, which is that weight stigma has terrible health effects for children. We see that weight stigma is incredibly linked to eating disorders, which have enormous prevalence worldwide. One in five children and adolescents show patterns of disordered eating, with girls being disproportionately affected. And one of the biggest triggers for disordered eating, sadly, is being categorized as overweight by her parents. And that often does start at the doctor’s office for many girls. Another big trigger is being put on a diet. And then later in people’s lifespan, we find that weight stigma has these independent marked health-ill effects. So you add up the pieces of this picture with larger people facing really inadequate medical care, facing weight stigma, facing many other forms of bias and treatment that will have marked health ill effects, and then is it any wonder that there are correlations of heavier people having certain health problems?

Now there is, as far as I can tell, based on my philosophers look at the empirical research, I’m not a doctor, I’m not an epidemiologist, I’m not a medical researcher of any kind, the really open question in this field is: is higher weight causing people to have greater health problems, or is it mere correlation? And that’s an open question because there is so much going on when someone gets to a heavier weight, including weight bias, including lack of adequate medical care, including confounding factors. They might not be getting the kind of exercise that we know is very good for the human body. There might be confounds of what people are able to access in terms of their diet. We really shouldn’t be assuming that people’s weight is the primary driver for health outcomes being negative. We should be open-minded that this may be mere correlation and that a lot of what’s going on in these cases could be that weight stigma is driving these differential outcomes for people who are very heavy.

And again, these sorts of correlations don’t kick in until higher weights than are often assumed, a BMI of maybe 35 or 40, according to some studies. So people who are in bodies that are classified as “too fat” are often not at greater mortality risks than average weight people, with overweight people, in fact, being the healthiest category, statistically speaking, and “moderately obese people” having the same kinds of mortality risks as people who are in the so-called “normal” weight category. But those health ill effects that are on many people’s minds when they think about these topics, if we want to address those for very heavy people, then we should get really serious about facing weight stigma and weight bias, that is at least part of what is going on in these cases as well as sheer weight itself.

is higher weight causing people to have greater health problems, or is it mere correlation?

AA: Maybe we can dig in on a few of those specific issues, because your book challenges a lot of very commonly held beliefs that were really surprising to me. Maybe we could talk about a few. Some that stood out to me were, again, you’ve mentioned the overall health risks, which turn out to be not what everybody’s told, and then specifically correlation with diabetes. Maybe you could talk about a couple of those.

KM: Yeah, totally. One of the biggest incontrovertible correlations that we get in this domain is that Type 2 diabetes and being a higher weight are highly correlated, and that’s certainly true. But some of the emerging research in this field shows that it may be that the causation is partly going in the other direction and that early diabetic processes such as insulin resistance are driving weight gain rather than weight gain driving early diabetic processes. So according to the best cutting edge research in this field, we have to be careful here to make simple, straightforward assumptions when the reality is that the relationship between weight and health is really complicated.

And another piece of it that I think is worth mentioning here is that many studies show that some of the risks, maybe all of the risks associated with being in a larger body are mitigated by fitness. So the studies are very clear that dieting is not generally something that is long-term beneficial for people, because most people who do lose weight will regain the weight that they lose, oftentimes repeatedly in a process that is known as weight cycling. And weight cycling turns out to have independent health ill effects on the body, like cardiovascular problems, like metabolic problems, it actually increases rates of Type 2 diabetes, immune dysfunction, and also mental health difficulties. But although dieting doesn’t seem to be particularly good for our health long-term, exercise is really terrific for most people, as long as they find a form of exercise that suits their bodies. And a lot of studies have shown that people who are fat and fit have similar profiles in terms of cardiovascular risk to people who are thin and fit.

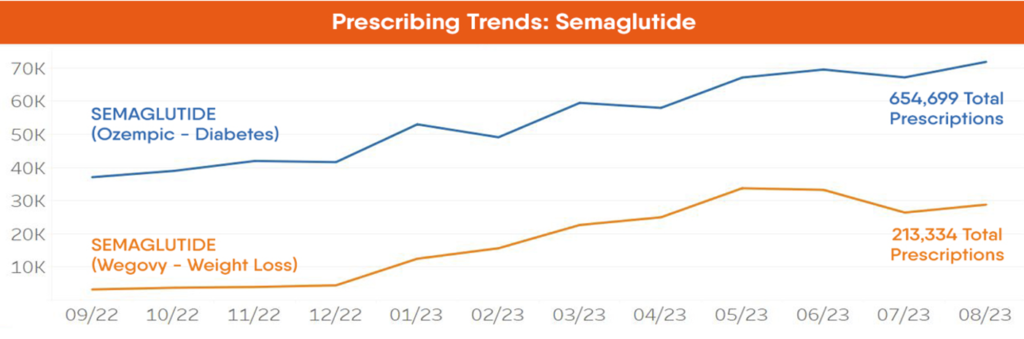

So it may be that we are emphasizing the weight piece of this very complicated puzzle too much and that fitness, not fatness, should be emphasized as what we need to intervene with. Partly because people can usually, if they have access, improve their fitness in various ways or continue health practices to do with fitness that they’re already engaging in. It’s a behavioral change. Whereas people can’t directly reduce their weight for the long term, at least via these interventions of diet and exercise that don’t, on average, reduce people’s weight in the long term. So, study after study shows that people can lose a moderate amount of weight on any number of diets, but the weight comes back really inexorably for the vast majority of people, and between one third and two thirds will end up heavier than they started. So intervening in people’s fitness practices looks like it might be a more realistic and practical intervention than trying to reduce their weight long-term, which doesn’t look like we have safe, effective, humane ways of doing in the long-term at the moment. And we can get into it if you would like, but this is also a worry that applies to the new class of weight loss drugs, like Ozempic and Wegovy semaglutides, because most people who go onto these drugs do end up going off them because of costs and side effects and then the weight regain is pretty rapid and nearly total within a year of discontinuation.

AA: This is so important, Kate. And like I said, with all of these other issues too, this is not what we learn, right? We have trusted sources that have been telling us the opposite for so long. So this is just so important.

KM: Yeah, thank you. It was surprising to me while researching this book, I often expected to find a different picture. But for readers who do want to dive in, there are also really interesting longitudinal studies that I cite in the book, showing that for large populations of people, often the best outcomes seem to belong to people who maintained their body weight rather than intentionally losing weight. And so, yeah, this really did defy even some of my assumptions about what this relationship would be, as well as the feasibility of long-term weight loss that it just looks much harder to achieve than many of us have been told all throughout our lifetime.

AA: Yep, totally. And I’m thinking of a hundred personal experiences that we could talk about, but we won’t. But yeah, this is really important. The next thing that I wanted to talk about is the BMI, and you mentioned it already in the episode, but this was mind-blowing. There’s such an interesting story behind how it came to be, and then the stigma and the problems that it’s created. So, can you tell us the story of the body mass index?

KM: Yes. It’s a simple function of people’s height versus weight. And this was developed, and here I’m drawing on brilliant history on the subject by Sabrina Strings, the sociologist and the fat activist and podcaster, Aubrey Gordon, who’s written extensively on this subject. And what they have illuminated, among many other authors too, is that the BMI was developed originally based on the ideas of one Adolphe Quetelet, who was a 19th-century Belgian astronomer who decided that the average body was the ideal one, which just doesn’t follow. But also his average body was based exclusively on Belgian military men in the 19th century. So why we should be regarding this as the standard normatively for human bodies today is anyone’s guess.

But this was adapted during the 20th century by Ancel Keys in the 1970s to become the BMI that we know today, and it just has so many flaws. It doesn’t differentiate muscle versus fat on someone’s body, it doesn’t make accommodations for different racial groups, which often have different relationships with weight and health. It doesn’t accommodate the fact that different age groups have different kinds of statistical relationships between getting older, for example, means that having a certain amount of fat on your body actually turns out to be protective. So there are just so many people who get classified according to their BMI as being too heavy, when according to their particular race and age, they’re actually in a class of people who are protected by being in this BMI category. But it’s just way too monolithic. And yes, it really doesn’t make the kinds of fine-grain distinctions that would be useful in this connection. And it’s notoriously bad at assessing the health particularly of black women and of people who are over 60. It’s a really crude measure, and it was never intended to be a measure of individual health. It was intended as a population measure. And it didn’t even represent anything like the population that we have today.

AA: Yeah, that’s so important for people to know. I remember going to PE classes in college and having to weigh in, measure ourselves, they had calipers for us to pinch different parts of our bodies, and it’s just so anxiety producing I think across the board for everyone. But again, your book helped me realize that this is so much harder for some people than others, too, but just how arbitrary it is to be based on men. So how could it even be relevant to any female bodies?

KM: Yes. And it was changed arbitrarily in 1998 to fall in line with the World Health Organization’s latest recommendations. But it used to be that a BMI of 27 or 28, depending on gender, was where you began to be considered overweight, but now it’s a BMI of 25. And there was no particularly good reason for that change. Part of the rationale was just to have a nice figure that would be easier for doctors and patients to remember. So again, it was really not based on measuring populations and figuring out what health risks started at what weight for different people. It really is a very arbitrary and crude measure and incredibly reductive of human bodies. Especially when we can measure lots of health outcomes directly and in ways that are much less stigmatizing. We can take people’s blood pressure, and we can give them blood work, and we can do all sorts of much more fine-grained and probative stuff that doesn’t involve just making them weigh themselves in school in ways that contribute to some of the fat stigma that I’ve mentioned. And it really doesn’t take into account individual differences.

AA: Yep. You mentioned how race can intersect with anti-fatness and fatphobia. Could you talk about that a little bit more and talk about how fatphobia is a form of structural oppression that intersects with lots of other forms of structural oppression?

KM: Yeah, this is a crucial piece of the picture. And here, again, I’m going to draw on really groundbreaking work by Sabrina Strings, the professor of sociology at UCLA, who has shown that fatphobia is a really quite recent form of systemic oppression. This isn’t to say there aren’t notes of anti-fatness in human history. It’s patchy, it’s mixed, but oftentimes fat was regarded as a sign of luxury and wealth and abundance until the mid-18th century, when what happened basically was the slave trade was burgeoning in England and France. And with that burgeoning of the transatlantic slave trade in the mid-18th century, white men were looking for a way to differentiate white bodies from the Black bodies who they were enslaving so brutally and in ever increasing numbers. And it was then that an association between fatness and Blackness began to be drawn, not based on any actual empirical science or data gathering, but based on racist pseudoscience that held that the black body was fat. And then held that fatness was a sign of being “primitive” and “barbaric”, all of these incredibly hideous racist notions. So we need to be very clear about this history. I think it’s not that fatness was derogated, and then fatness and Blackness were associated, it’s rather that fatness and Blackness were associated, and then fatness came to be derogated shortly thereafter in order to justify practices of slavery. And this is then seen ratcheting up in the norm that then white American women, particularly Protestant American women, were highly subject to thinness becoming more and more “in” during the 19th and then 20th centuries.

And this has resulted today in a set of tragic intersections that are illuminated both by Strings and the scholar Da’Shaun Harrison, who has shown that the idea of the fat Black masc body is often used now as a pretext for police brutality. So Michael Brown in Ferguson, Eric Garner in Staten Island, these men were horrifically murdered, state executions by cops who used the size of their bodies in various ways to justify these inexcusable acts. So, the intersection between racism and fatphobia kills.

AA: I’ve also never felt more moved by Lizzo, like the album cover of her. I was just listening to some Lizzo songs and I glanced at my phone and saw the little thumbnail of her album cover, which is her nude body, just unapologetically front and center. And I mean, I always thought that was really striking and really great, but the courage and kind of the political act, I guess, I thought of it more as a personal act or an emotional or a psychological act, which it is all of those things, but it is kind of a political act now that I think about it.

KM: Completely political. Because often Black women’s bodies have been the ones who have been targeted by racist and misogynistic forces, where their intersection, for listeners who haven’t heard this term before, is called “misogynoir”. And this is a term coined by the Black queer feminist Moya Bailey. And so much of the intersection between misogynoir and fatphobia takes the form of shaming Black women for their bodies, their body size, and then neglecting them within the healthcare system in ways that can have really tragic outcomes.

So we both troll that, “We’re so concerned about Black women’s health,” because Black women do happen to have the highest average BMI of any comparable subgroup in America today. But Black women also face the fewest health complications at higher BMI categories, and yet we troll, we hand-wring about Black women’s health. And then when you actually look at what is being done to help Black women’s health, we see that actually they’re facing horrific negligence and misogynoir within a medical system that, for example, has resulted in Black women having three to four times the maternal mortality rates as white women, because they’re so not served by the medical system as it exists. So if we actually want to improve the health of Black women, why not improve maternal medicine for Black women who are not being treated adequately and are facing huge health risks because of the system, not because of the size of their bodies?

So, yeah, I ended up not talking as much about Lizzo in this book just because there is current controversy about how she has treated some of the people in her employment, but people can be complicated.

AA: I didn’t know that.

KM: Oh, yeah, there have been huge lawsuits and controversies about this, but there is no doubt that some of what she has done in terms of fat Black women representation has been a real force for good in the world, and that is an incredibly brave political act. Even though there are questions about other aspects of the treatment of workers that are still being resolved and which we should be concerned about.

AA: Thanks for pointing that out. One of the most striking pieces of data that you share in the book, that was really arresting for me, was you talk about this research project at Harvard in 2019. And this is a research project on implicit bias, so the things that society as a whole has negative bias toward, and it was race, skin tone, sexual orientation, age, disability, and body weight. And of all of those biases, anti-fat is the only one that has gotten worse since 2007. All the others have made progress and people are more empathic and more compassionate. Anti-fat has actually gotten worse in the last 10 to 15 years. And your book says that the majority of people canvassed still harbored explicit anti-fat biases in 2016. What are those negative biases that people have toward fatness and why do you think that this is happening, Kate?

KM: Yeah, it’s so important. And I want to be clear that sometimes these results are construed as fatphobia as the last acceptable prejudice, and that is not true. If only that were true, but unfortunately it will never be the last acceptable form of prejudice. There is still enormous amounts of homophobia and racism and sexism and all of it. But it is true that I think there’s a certain complacency among liberals and progressives when it comes to fatphobia, which I think shows up in the way that this was the only form of implicit bias that, just as you said, is actually increasing and it was the form of explicit bias that was decreasing the most slowly of any of the biases studied. And they didn’t study every form of bias, but they did study, as you said, disability, race, skin tone, sexuality, and age as well as body weight.

So, I think there are a couple of reasons why we might see this. One is that there has been a kind of moral panic about the so-called obesity epidemic, and there has been a labeling of “obesity as a disease.” Which, look, I think some people who are in larger bodies view that as a helpful way of framing things, which reduces personal blame for them. But I think that, from my perspective, we actually see increasing amounts of stigma when we label something as a disease, when it’s at most a risk factor for actual diseases. And certainly the labeling of obesity as a disease, there is some evidence that it was driven more by the attempt to sell weight loss drugs than by the actual medical reasons to do this. So the advisory committee to the AMA that made this decision to label obesity a disease actually recommended that the AMA shouldn’t call obesity a disease because it was based on the BMI, which is notoriously problematic. So that’s one reason that we see a lot of moral panic about increasing numbers of fat people and the health status of fat people that is both somewhat exaggerated in terms of, yes, there has been a real uptick in rates of fatness, but it is partly a response to the fact that the change in classifications for overweight and so-called obese bodies, which was made in 1998, means that some of that uptick is just a product of change in classification standards.

And also, as we’ve discussed, while I would certainly never deny that there are correlations between being very heavy and having certain health problems, we can be too quick to assume that it’s causation rather than mere correlation. And certainly people who are judged to be too fat by the medical establishment often don’t have elevated risk factors for certain diseases. At a BMI of 25 or 30, there really isn’t statistical evidence that you’re at this elevated risk, that doesn’t kick in until a heavier BMI of 35 or 40. So that’s one of the reasons that the biases increase, this real discourse about “what are we going to do about all the fat people?” That is both stigmatizing and often really oversimplifies the picture that is complicated.

But I think part of it too is a failure of political solidarity. So as fat people, and I completely understand this, but we’re often tempted to think about there being a thin person within us, kind of waiting to break free triumphantly. That the next diet around the corner will yield a thin person. And so we don’t tend to necessarily want to identify as fat, we see ourselves as merely temporarily fat, despite the evidence that for someone who was classified as I once was, as “severely obese”, the chances of ever achieving a so-called normal weight is vanishingly small. It’s under 0.1 of a percent. But we don’t see people really joining forces with other larger people. We see lots of people wanting to escape that classification. And as a result, I think, although of course there is a rich and powerful tradition of that activism, it still doesn’t have quite the political momentum that I wish it did. Thus resulting in these biases not really being challenged quite as widely and effectively as would be healthy and make for greater justice for people of every size.

AA: Well, hence the need for your book, right? Because that’s the consciousness-raising piece of this, I think, at least so more people are educated about it. And again, more empathic and compassionate and actually know the real data and the real science behind it. So hopefully this can start to change the culture.

KM: Thanks. I mean, I just see it as one small piece in a bigger conversation, but I’m glad to lend my voice to what feels like a growing choir of people saying, “Hey, this is a political issue and we need to be serious about it.”

AA: Yep. I’ll say one term that came up in this section of the book, and maybe people know this term but I hadn’t heard it before I read your book, is “concern trolling”. And that was so, so accurate when I think about the conversations I’ve had with people about weight issues and, like you said, the panic over the “obesity epidemic”. That people just say, “Well, I’m just so worried” and you get this right on the micro level in families, a mom saying to her kid, “Oh, I’m just worried about you.” So can you talk about concern trolling a little bit and whether that’s actually compassionate or helpful or not?

KM: Yeah. I mean, I have the general belief that one’s body is really no one else’s business. And so a lot of what happens is both disingenuous and intrusive. Asking someone in a supposed tone of concern, “I’m worried about your health,” often feels like a form of judgment and shaming when it’s attached to weight rather than being like, “Can I do anything that would actually be helpful and productive in your life?” It feels like adding to the weight stigma that has demonstrably bad health effects. And in addition to that concern, the concern is often not really coming from a place of actually wanting to help someone as evidenced by the fact that a lot of concern trolling about fat people’s health is offered by people who wouldn’t take basic safety precautions for public health like wearing a mask indoors at the height of the pandemic or getting vaccinated. So the fig leaf is a little bit off after the pandemic. Some of the people who are most worried about the health of fat people aren’t doing the kinds of things that are useful ways of contributing to the public good of collective health by helping not spread, say, contagious diseases and illnesses. So that’s part of it.

there’s a certain complacency among liberals and progressives when it comes to fatphobia

But also oftentimes it’s a way of saying that someone’s body is attracting negative attention by that person and that their body looks like it may have gained weight or become larger or whatever it is, where I promise that a person in a larger body is acutely aware of their size and of weight gain and doesn’t need it pointed out to them. And similarly, you would have to be a fat rock-sheltered Martian to need the advice that “diet and exercise, diet and exercise,” or to miss the memo that there is a new class of weight loss drugs on the market, like Ozempic and Wegovy. So yeah, what are these conversations meant to yield is a really good question to ask for anyone tempted to engage in them. And the likelihood is that they’ll just make someone in a larger body feel stigmatized and othered and alienated, and won’t help her one bit. So, yeah, a lot of these conversations just need to be retired.

AA: Hmm, absolutely. Well, that brings us to the end of the conversation, Kate. But I did want to close by asking, and this is kind of what you’ve just been talking about, maybe for some takeaways for listeners who identify as fat, what would be a takeaway or two for them? And then listeners who don’t identify as fat, what would you want a takeaway to be for them?

KM: I think for listeners who identify as fat, I would say first of all, sympathy and solidarity. It’s really hard to be a person in a fat body facing a fatphobic world. And that I am someone who believes that you’re entitled to do what you want with your body and that I know many people who identify as fat do want to lose weight and I certainly don’t begrudge anyone that journey. But my concern is that for those of you who are in larger bodies, that many of us feel obligated rather than merely entitled to lose weight, and that the weight loss isn’t permanent in most cases. And to talk about my own case for a moment, I was in a much larger body and I was really healthy and really happy but for the fatphobic world. So I think it’s worth considering: Is this problem the world’s or is it my body’s? Maybe we’re made to feel that our body is the problem when it’s actually the fatphobia that’s plaguing us. And there may be in some cases a sense that we need to shrink ourselves when actually we’re just fine the way we are and should embrace our fatness as just a valuable form of human diversity. Which is, I know, a controversial view, but it’s how I’ve come to look at it.

And for those who aren’t in fat bodies, there was a really useful question asked by Aubrey Gordon on her Instagram that I think is actually applicable to anyone but especially thinner people, which is: How are you showing up in the world for people who are larger? This year, or for that matter, full stop, are we making an effort to combat fat stigma and fat-shaming? If someone we’re in conversation with starts concern trolling about people’s health or making fun of someone by saying, “Looks like they’ve enjoyed too many slices of pie,” or whatever. Are we making an effort to intervene as we would with a form of bullying that is more commonly recognized? Are we making an effort for the kinds of inclusion that are material? Do we, for example, as a teacher, and this is something I face when I go into my classrooms at Cornell, do we have a classroom that will accommodate a range of body shapes and sizes in the very simple sense of having some chairs without arms that would be comfortable for people who are in larger bodies to sit in without feeling constrained and restricted? Are we making an effort to contribute, for example, to the efforts to legislate against weight-based discrimination which are taking hold in certain states?

So, for listeners who don’t know, weight-based discrimination is legal in most places currently. It’s only illegal in Michigan and Washington State at this time, and there are also some jurisdictions, including now in New York City, that have banned it. But states like Colorado are introducing this legislation, and it would be really helpful for larger people to be able to sue their employer for discriminating against them based on weight or for not hiring them based on weight. So those are just a smattering of the efforts that I hope the book reveals we can contribute to, regardless of our body size, to make the world just and kind and inclusive towards everyone, regardless of what you think about the relationship between weight and health. You can probably do better in supporting people with a range of body types in living the best, happiest, healthiest lives they can without contributing to the weight stigma that really ails us.

AA: Beautiful. Well, Kate Manne, thank you again so much for being here. Thank you for all of your work. Thank you for this book, and listeners, I can’t recommend it highly enough. It’s called Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia. And again, I recommend that you read all of Kate’s books.

KM: Thank you so much for having me, Amy! It was a delight.

we can be too quick to assume that it’s causation

rather than mere correlation

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!