“patriarchy wants us dependent on everyone but each other“

Amy is joined by Beatriz Albina, NP, MPH and host of the Feminist Wellness Podcast to discuss the wear and tear of patriarchy on our nervous systems plus practical strategies for overcoming “good-girl training” and restoring our dysregulated bodies.

Our Guest

Beatriz Albina

Beatriz Victoria Albina (she/her) is a Master Certified Somatic Life Coach, UCSF-trained Family Nurse Practitioner and Breathwork Meditation Guide. She helps humans socialized as women realize that they are their own best healers by reconnecting with their bodies and minds so they can break free from, codependency, perfectionism, and people-pleasing, and reclaim their joy. She is the of the Feminist Wellness Podcast, is trained in Somatic Experiencing, holds a master’s degree in public health from Boston University and a B.A. in Latin American Studies from Oberlin College. Beatriz has been working in health & wellness for rover 20 years and lives on occupied Munsee Lenape territory in New York.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Patriarchy is everywhere, and yet its structures can sometimes be difficult to identify. Its effects on our society and on our bodies, however, these we can clearly observe. We can collect data on it, and we have to respond to it. As longtime listeners already know, those effects of patriarchy on our bodies and on our health are often devastating. As Dr. MaryCatherine McDonald told us last year, “A patriarchal system is inherently anxiety-provoking. And for those of us most actively oppressed by this system, it instills a feeling that we are being oppressed and that we’re in danger, and our nervous system is going to respond accordingly.”

What do these responses look like? Maybe nausea, maybe digestive troubles, maybe breathing problems, increased rates of heart disease, mental health struggles that come from living life in a world where we feel unsafe and unwelcome. So, how can we regulate our own nervous systems as we navigate this patriarchal world? How can we take care of ourselves? And how can we stay committed to this work of breaking down these oppressive systems? These are just some of the topics addressed by a medical practitioner and host of the podcast Feminist Wellness, Beatriz Albina. Welcome, Beatriz!

Beatriz Albina: Thank you so much for having me! I’m delighted to be here.

AA: I’m so excited to have you and really excited to dig into this discussion. Beatriz Albina is a functional medicine nurse practitioner, an herbalist, a certified breathwork meditation practitioner, and the host of the podcast Feminist Wellness. Her work explores the connection between trauma, the nervous system, and healing our bodies through somatic practices. As I said, I’m so excited because I feel like, especially right now, we were just talking before we hopped on the recording, we’re recording in mid January of 2025, right after the Trump inauguration, and I think a lot of people are experiencing a lot of dysregulation, a lot of physical symptoms of anxiety coming from the changing landscape of the world we’re living in. So this is very, very relevant and practical, the work you’re doing. I’m super grateful for it. But before we get into that, I’d love for you to introduce listeners to yourself by talking about where you’re from and some of the factors that went into making you the person that you are today and doing the work that you’re doing today.

BA: Yeah, so I’m from Mar del Plata, which is in Buenos Aires, in Argentina, and I grew up in the great state of Rhode Island, thus, you know, the thick South American accent in English. And I grew up feeling very apart, right? We were the only South Americans that I knew, and I was not like the other Latina girls, the Puerto Rican and Dominican girls. I always felt like this bicho raro, like a weird bird, like I never really fit in. And it’s been so interesting to have all these conversations about the political landscape, about our nervous system, about somatics, and to start to really locate little me, the me that got me to here within the framework of her nervous system, her social location, everything that was going on in her family, in her community, in her world, that led me to want to do this work. Which was the work of helping others to live intentionally, with purpose, with thoughtfulness and mindfulness from a regulated nervous system. And a nervous system that can feel all of the massive feelings that I didn’t have the capacity to feel as that little tiny immigrant baby, and I’m definitely feeling right now as all of us who are paying attention and have our eyes open are aware of what a horrifyingly frightening moment this is for every immigrant in this country, for women, for trans folks, for queer folks, for everyone other than cis white straight dudes with money pretty much, right? So, yeah, it was a bit of a roundabout way to introduce myself, but I got here because I wanted to help others to find the healing that I had found around my identity, around my personhood, and how that related to my nervous system.

AA: Hmm, that’s really beautiful. Thanks for being willing to share that. I have the joy and the privilege of knowing and loving many immigrant families, and there’s a sacredness to me of parents who immigrate with children and make that bridge to what can feel like a different planet, a different world. I just think of what your parents must have gone through making that journey as adults, especially if you’re saying they came when they did after Argentina had been through such a terrifying time, and wondering what tools they had to regulate their nervous systems during that. That’s actually traumatizing to out yourself from everything you know and come to a new place. Would you be willing to talk about that a little bit?

BA: Yeah, I mean, it is with great respect and love to and for them, I will very honestly say, I don’t think they had many skills and tools. And I think a lot of people of their generation and their moment, specifically their generation in Argentina, did not have the tools that we– I mean, we can problematize Instagram in a moment, but we have Instagram. We have the internet, right? We have all this #healing, we can know so much and communicate with people across the world and work things out in ways that in 1983 Rhode Island, like, what did my parents have access to? Very little, you know? So I’d give a lot of grace to them doing the best they could within their nervous system capacity. And to broaden it, that’s not to let people off the hook for harm and for effing up and for not supporting and ba ba ba ba. And… were they playing with the full deck? Not really, because how could they have gotten those skills?

AA: Yep. That just encapsulates the attitude that I really strive for in my life with difficult relationships, just having that nuance and that space for accountability and also compassion and love.

BA: All of it. Well, and if our goal is to create a more just and loving planet, which like, what is feminism? It is that desire embodied. And so it behooves us to both start with ourselves and our inner children and honor what was lousy, grieve it, feel it, have sacred anger about it, have sacred rage about it, be in a process about it, and having given ourselves that love and care, pull back, and see what we can then offer in terms of compassion and empathy to people who don’t have everything we have available to us now.

AA: That’s awesome. I’m curious about your steps, the steps that you took growing up where and when you did, how did you gain the tools? How did you gain the skills? How did you even know that there were additional– that there was this other path that you wanted to take? What were some of the steps in your journey?

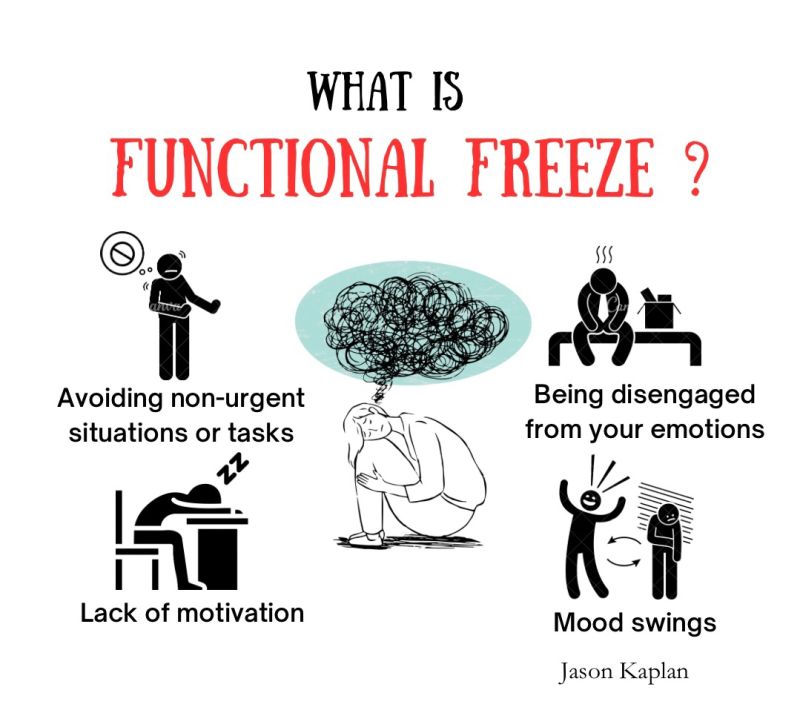

BA: It was circuitous, to say the absolute least. Man, I went around the globe to come back home to myself, the way we so often have to. I don’t know how I found Oberlin College, like, from a paper pamphlet in 1995 or ‘96, but I’m really glad I did, because going to weirdo school was really one of the top 10 best choices I’ve ever made. And if you’re out there with a college-aged kid who’s a weirdo, or too smart for their own pants, send them to Oberlin, especially the confluence thereof. It taught me to think. That’s the best skill I learned at Oberlin, was how to think and how to question absolutely everything while naming my social location, while naming my privilege, while being intellectually honest. And I know that that has been the bedrock and the foundation for everything else I’ve done. I will also name that my nervous system was absolutely in a functional freeze while I was at Oberlin. And we can talk more about that and describe that and get into the science if you’d like, but the short and long of it was that I was functional on the outside, so functional– do you want me to nerd out?

AA: Please.

BA: Okay, great. You know, consent. Consent to nerd.

AA: Nerd away.

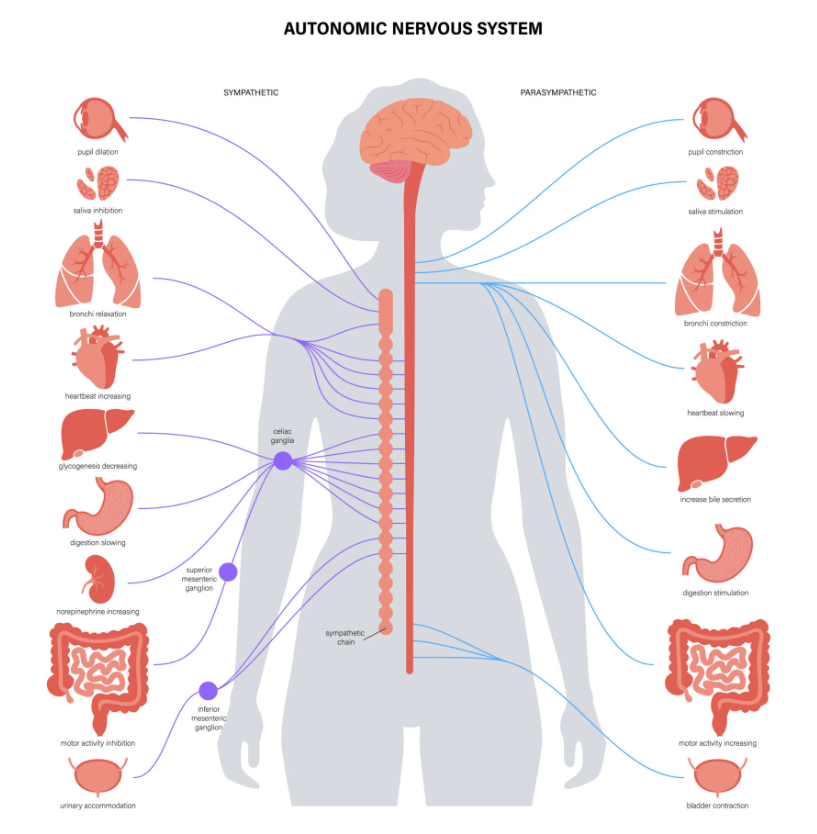

BA: So, what we’re talking about here is our autonomic or automatic nervous system, and it’s the nervous system of safety, dangers, and social connection. It’s constantly scanning the world and saying, “That sounds like a lion. Book it, run, faster,” or, “Oh, it’s a tabby cat. We like those. We took a Claritin, we’re fine, let’s snuggle it.” That autonomic nervous system has three parts: sympathetic, ventral, and dorsal. Sympathetic is fight or flight. Panic, freak out, run, lions. When that system gets exhausted and we’ve done all the running, all the screaming in a bad marriage, all the arguing at work, all the whatever we can, we’re exhausted, we go into the dorsal system, which in this way we’re talking about in the terms of safety and danger, dorsal is disconnect. In Spanish we say, “No doy más,” “I give no more.” It’s just like, “Yeah, okay, fine. You’re right. That’s fine. Okay, sure. Whatever you want. I can’t argue anymore. There’s no give left in my system.” In the wild animal, you know, an actual lion, that’s a possum playing possum, a deer in the headlights. You know how you walk up on a bunny and they’re suddenly a statue of a rabbit and they’re not going to blink if they can, right? That’s that dorsal, shut the animal down so that the predator doesn’t eat it, right? The predator thinks you’re dead, it moves on. In humans, it’s that checked out, you know when people are staring off into the middle distance when you’re talking and you’re like, “Hello, are you home?” They’re not. The lights are on, but you’re not home. These are two responses to stressors, and they can be two dysregulated ways of walking through the earth, anxious and revved up or checked out and shut down. Does that make sense so far?

AA: It does, yes. And I’m wondering if that dorsal state where you freeze and you check out, I think of the rabbit like you just described as it, being in that critical moment of like, “I’m going to try not to get eaten,” but I wonder if that can last for a long time in a human. Like in a relationship.

BA: In depression, yeah. Or right, like being in a relationship where you’re not being heard, you’re not being seen. This happens for a lot of kids, I think particularly kids our age, kids raised by Boomers and the Silent Generation who weren’t being listened to. And I’m not throwing anyone under the bus, I’m just sharing what I’ve worked 20+ years of doing this work. When you’re chronically not listened to, you learn that you’re not worth listening to. You learn that your voice doesn’t matter, because it’s not going to be heard anyway. So why push, right? And I think a lot of us have been there, particularly in patriarchal systems where we’re like, “You know what, why bother? I’m going to save my energy for not this.” Or we don’t have that awareness and that consciousness or the capacity to make a decision like “I’m going to save my energy,” and our body just checks us out in a way without our active consent. With our cellular consent, but not with our conscious mind’s consent. So we just check out of life.

And you see that in the kid who’s quiet and depressed at home, but super hyper at school with a teacher they trust, a teacher they feel safe with. “Oh, I love Miss Amy!” You get to class and you’re a complete banana boat with Miss Amy because you feel safe with her, and she loves you, and she listens to you. So your nervous system can have some spaciousness, and then you get home and you’re that silent, checked out, not present kid.

AA: Huh. Yeah, that makes sense.

BA: Yeah, they’re all survival skills, right? “How could I not be lunch?” But ‘lunch is…metaphorically, it’s more complex now. Because studies show that very few Americans are being chased by a T-Rex or lions. That’s just by the latest studies, I don’t know if you have more up-to-date studies, we can review those, but mine show… Yeah, we’ll look at the data, I trained in epidemiology. But yeah, and then the ventral vagal is the nervous system state where we’re chill. How I feel right now, I feel ventral vagal safe and social with a little bit of sympathetic, just a tiny touch because I’m happy, I’m excited, I love nerding about this stuff! And I saw your post about Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga the other day and I was like, “I cannot wait to talk to her!”

they can be two dysregulated ways of walking through the earth, anxious and revved up or checked out and shut down

AA: Yay, good! I’m so glad. That makes me happy.

BA: Oh my god, those two. I remember finding them my first year at Oberlin, finding them in the library and doing Chicana Studies and reading about them. It’s rare for me to lose words, but I noticed that I just, in this sort of sympathetic cascade of like, “Oh my god, so many feelings and so much excitement, and I just can’t even find the words,” but in the most beautiful sense of dorsal, where it’s like, “Ah, what those women mean to me!” Because they take you to Audre, who takes you to bell, who takes you, who takes you, who takes you.

AA: Yeah. Oh, I’m so happy to hear that. And I’m so happy to know that you found them so early in your adult life. And thank goodness that you did go to a place where you were taking Chicana Studies and that there were copies of those books in your library, because a lot of people don’t have access to that. So glad. Because it sets you on your course early on and you don’t have to waste all those years not knowing.

BA: Right. And so even though I was describing functional freeze, which is what got us into the nervous system. So, functional freeze is when you’re in that sympathetic “I gotta go, gotta prove myself, gotta make sure these people know I’m smart, I gotta prove who I am, I gotta prove I’m good enough, proving, proving” sympathetic, but dorsal, checked out, disconnected, not home on the inside to yourself, to your feelings, to what’s really going on for, with, and in you, because you’re not present with yourself. And we’re usually not present with ourselves because of a combination of family blueprint and survival skills, along with growing up in white settler colonialism, late-stage capitalism, and the patriarchy.

AA: Yeah, that makes sense. You said that you were experiencing some of these symptoms or some of these responses in college, right? Where did that come from? What did that feel like? How did you develop coping strategies? Walk us through that.

BA: Yeah, well, I think it was very much that confluence I was just talking about, of family survival skills plus the multiplicities of oppression, while also having this, what felt at the time, I would call it guilt as a white Latina. Of feeling like the oppressor, but also a Latina. In college, really feeling like I had to fight for my identity while I was sort of figuring out my identity. It was a complex moment, and there’s so much complexity to being a white Latina. Like, come on. And this is not me with a tiny violin, no, the opposite. This is me owning my role as the great-great-great-great-great-great-granddaughter of the oppressor, and walking in white skin, obviously. So, the functional freeze was all of those factors. Also, it was really gray in Ohio. I’m going to blame the lack of sun just a little bit.

AA: That’s fair.

BA: Right? Just feeling so overwhelmed and not having the coping skills other than studying really hard. Other than like, “Everything feels like a mess. What do I know how to do? I can get an A+ and another one and another, and I can organize,” because my chart’s so much Leo and so much Virgo, I will organize. So I ran the Latino student union, I helped organize the hip hop conference, I got people together, but it was all external work. Do you know what I mean? Me was shut down. Performing, doing, making. And so when I flash forward 20 years to the work I do now, it’s all about giving context to that girl in Oberlin, Ohio, who felt like I was broken because I couldn’t see the systems. I couldn’t see the mechanisms. I couldn’t see the survival brilliance, which I now call emotional outsourcing. Can I define my term for you?

AA: Please.

BA: Thank you. So if you had told 18 to 30 year-old me, “Girl, you are so codependent,” I would have been like, “Ew, I’m not like a Midwest soccer mom.” I would have told you 20 cliches about who I was not, who was codependent. “No, that’s not me. I’m a strong feminist, independent woman. I mean, if you think I am. Do you think I am? Do you think I’m good enough? Am I strong enough? Am I feminist enough? Does my hair look pretty?” So I had all of the habits of codependent, perfectionist, and people-pleasing experience, but none of those words fit. I definitely was not a perfectionist because I was messing up so much. Not to throw myself under the bus, but sometimes I would get an A-. I know! Deplorable. Get out of the guillotine. But honestly, I wasn’t perfect. I got a 90 on an exam. Fool. I certainly was not people-pleasing, because who was happy with me? I was never doing enough. Ever. So I didn’t get help, I didn’t get support because I couldn’t identify with the terms that were the gateway to the help.

So a new term is needed, and a term that is in its way, because language creates everything. So extracting those terms from their origin, you know, “codependency” as a term and as a thing to deal with comes from the war on drugs. And talking about the “enabling wives” and creating more of a problematic group of problematic people related to the drug war. So then if it’s also on her, we get to push this pedagogy, as it were, even further. I could get lost in that, so I’m going to pull myself back. But emotional outsourcing speaks to what we do, and I define it as when we chronically and habitually source our sense of safety, worth, and value, and belonging, the most vital human needs, from everyone and everything outside of ourselves instead of from within, to our detriment. And that part’s really important. It is to our detriment, each and every time, when we don’t believe that safety, belonging, worth are within us.

AA: Yeah. This is fascinating. What just came to my mind is how I know, well, I’ll talk about myself. I was going to say, “I know a lot of women who-” but I’m just going to say me. I know that my sense of worth for a long time came from the validation of the church, the institutional church that I was a part of. It was telling me, “Here’s how to be a good person. Here’s how to win God’s love. Here’s how to win the approval of your community that you were raised in. Here’s how to be a good person.” And I so desperately wanted to be a good person. Who doesn’t, I guess. So here’s a checklist. I had a Mormon checklist and I checked all the boxes and did all the things. And you realize that that’s never enough. And there can be, I mean, I would say in some ways that I was lucky to have positive relationships that were based on real unconditional love and I had some good things going for me too, and some good self-esteem as well, but I was definitely wanting to prove myself as a righteous and smart and one of the good girls of Mormonism. But the thing that I was thinking is that a lot of times, even once people leave that and they kind of abandon that checklist, then they transition to maybe, “Okay, instead I’m not going to be that Mormon woman who just stays home and does domestic stuff, I’m going to enter the workforce.” And they just traded in for a different list. Or they entered even this feminism space, and I’m actually examining myself right now and just thinking, “Am I still just trying to prove myself?” And I’ve just given myself a different checklist of, “Well, now I’m going to be ‘righteous’ in this different way. I’m going to be the best historian and feminist and scholar there is,” but still, I’m just asking myself how much of this is truly coming from me. And I was born to do this, but my self-worth isn’t dependent on how many people approve of what I’m doing.

BA: Right.

AA: I don’t know. I’m just kind of exploring that in my own mind. Does that check out for you and what you see?

BA: Oh, for sure. We are nerds, and nerds will nerd. And it’s a beautiful thing for nerds to nerd and to really strive to be a complex thinker on a subject and do the best job exploring and extolling the thing you are so passionate about. I think that’s endlessly beautiful, right? But, and I think the point that you speak to so eloquently, is about self-worth. Does someone else saying, “No, mi amor, you did a great job,” is that when you’re like, “Phew, okay, now I can relax”? “I got my value. My drinking in of oxygen is approved of for today.” The metaphor I use is – I use a lot of metaphors, I’m Argentine, you know how we do a lot of metaphors – be the cake. Cake is perfect, cake is delicious, cake is amazing. There’s no beef to be had with cake. And icing is really lovely, but cake is fine on its own. Cake knows it’s amazing. If you ever really look a cake in the eye, it knows it’s incredible. And that cake and icing go well. So how does this play out in real life? If you are being your own cake, you know that you’re smart enough, good enough, thin enough, fat enough, pretty enough, shy enough, ba bi ba ba. You are enough, enough, enough, enough. But like yesterday, I was at my friend Melina’s and they went, “Girl, you have great skin.” And I was like, “Oh, aw!” And it felt amazing. I soaked it in. And I said, “Oh my goodness, thank you so much.” And it made me feel great. Not because I’m dependent on others to tell me nothing, but because I know I have great skin, and that’s why I don’t spend time with all the little cremitas. It just was icing. It was just icing.

AA: I was just going to say that that’s such a good metaphor. Because I was thinking, like, how can I tell the difference? How can I tell the difference? And that is a really great metaphor. Would I be fine without it? You’re good. But it does feel good to get that validation. It does, but there’s nothing wrong with that feeling.

BA: No, it feels so good. And even your smile when I told you I loved your work on Gloria Anzaldúa, aw, it feels so good. I think also just to say that those of us who sit in these little book-lined rooms nerding out and talking into a microphone all alone for hours and hours, there’s something really important and special about having that co-regulating nervous system moment where my nervous system says “Aw,” and yours can say “Oh,” and we can just connect mammal to mammal, eye to eye. There’s a beauty to it that’s beyond productivity, beyond perfectionism. It’s just mammals. If we were two little squirrels in the forest and I brought you an acorn, I’m sure you’d be like, “Aw dude, thanks for the acorn.” And that’s a sweet little mammal moment.

AA: Totally. I love it. And also, and thanks for mentioning that again, because I do think too that part of my joy, which I didn’t realize was reading so much on my face, but part of that, and you can understand this too, is me laboring with my books in isolation and then thinking “I’m doing this because as an educator, you want to educate and you want your work to reach other people.” And so like, “You found it!” I did this thing hoping that people would find it, and the fact that it found you organically just makes me so happy. But then, and this is the next thing I wanted to ask you, here’s the tricky thing. Social media, because you mentioned we might talk about social media, and I am constantly really interrogating my reactions and my sense of satisfaction that comes from, “Oh my gosh, this video we did got this many likes, got this many shares.” And there is, I think, a valid part of that, which is the work I’m doing is helping people, maybe that’s the cake, but I can feel why social media is so dangerous for people’s mental health, because it is hard to not seek the likes for the likes and then have that validate your sense of self. Anyway, I’m rambling now, but tell us about that.

BA: I don’t think you’re rambling. No, I think you’re bringing up a really valid point that a lot of us really struggle with, particularly those of us who are podcasters and entrepreneurs and have businesses where we are dependent on these systems. And I think it’s one thing to have this conversation a month ago, or in 2024, where all it was doing was destroying our brains, our sense of self, our dopamine systems, our sleep, potentially increasing dementia. Oh, that’s it. But now with the changes to Meta in the last five minutes, it’s gotten so much more insidious. So, I don’t have an answer. I do know that we need to look away from it and not let it consume us. I believe I got shadowbanned towards the end of December because I constantly post about Palestine and I constantly post about COVID safety because I care about oppressed communities. All of a sudden, my posts weren’t having views, my videos weren’t being seen. So, I did what they tell you to do and I deleted the app, but I had my team not post and we all went off it for six weeks and were talking early in the new year about how much better we all felt.

AA: A social media cleanse.

BA: Yeah. And I think that really teaches us something, right? It can be quite the stand-in for social engagement when we’re not getting it elsewhere. But at the end of the day, it’s such a false– I mean, let’s stay with the cake. It’s like that saccharin-y sugar high, right? Where it feels sweet but then you have a nasty headache because it’s not actually feeding you. And I think our nervous system knows that. And I think it’s particularly, you know, right now where I opened it for two minutes this morning and it’s all the Mango Mussolini screaming and the South African dude definitely doing a Nazi salute. I’m trying to not say names and get you censored.

AA: Oh, I don’t mind. You can say it.

BA: It is not good for our nervous system to be exposed to that flashing of the violent, hateful, aggressive, socially, morally, ethically bankrupt, everything that’s going on in the U.S. right now.

AA: Yeah, for sure. And one thing that we’re trying to focus on in this season of the podcast is being really intentional and deliberate about consuming news and letting into our lives enough information that we’re educated, and yet we can move through the world and do good in the world and know what’s happening, but to not get twisted up and sucked into a vortex over things that we actually really can’t impact and we have no control over. Because then that robs us of our energy to do things that we can control. So, to back up a little bit, I want to talk more about the perfectionism, the people-pleasing, and that overworking that you were describing that you were doing in college. I’m wondering if you think that is a result of a dysregulated nervous system, maybe you were experiencing the harms that come from all of those systems that you were talking about and so you had a dysregulated nervous system, and so you were doing those things to soothe yourself. Or, what do you think is the relationship between those things?

it feels sweet but then you have a nasty headache because it’s not actually feeding you

BA: I think it’s both, right? I think doing and doing and doing, and focusing on production and productivity and performing, doing things for other people, in particular, is a massive buffer against feeling our feelings. When feeling our feelings was stupid growing up, was dangerous growing up, was negated growing up, which for a lot of us in immigrant households, and I’m sure it’s regular– “regular,” you know what I mean. I think it’s a really common thing to have our feelings feel like a burden growing up. I hear this from my clients day in, day out, that if they expressed a feeling, it was like, “Quit your crying, I’ll give you something to cry about” kind of vibes. And so you learn to negate the feelings, but the feelings arise. Okay, let me back this up to talk about the nervous system again. What do you feel when a lion’s chasing you? Fear, which can also come with anger. What do you do with those feelings within you that tell you, “Get the hell out of here. Run, fight, flight.” If you cannot express them, they get shoved within, but that revved up energy that’s secondary to adrenaline and norepinephrine, they stay within your organism. As long as your body’s pumping them out, they’re in your bloodstream. It’s pretty clear science. We need to channel all that adrenaline into something or we just frickin’ explode, right? That’s when people start throwing lamps and screaming at the top of their lungs, “blah, blah, blah!” when you’re not doing something with it.

But if you’ve been good-girl trained, if you’re living in that emotional outsourcing where everyone else’s thoughts about you are the most important thing, the apex of vitality, bueno, what are you going to do? Clean the house like a frickin’ tornado. You’re going to vacuum behind the microwave by taking it out of the wall. You’re gonna clean, you’re gonna organize, you’re gonna bake, you’re gonna sew, you’re gonna do, you’re gonna do. And if the domestic sphere is the safe sphere, you’re going to do and overdue and over function there or at work or in your studies or in athletics, or whatever it is for you. We use over functioning, overdoing as this incredible buffer and, mija, I’m not going to diss it completely. It works until it doesn’t. If you have absolutely no skills and tools to feel your feelings, they will overwhelm you. It makes sense, right? And so it keeps us from going into full-fledged panic. So I’m really careful not to malign our survival skills because they are survival skills. And if you’re in a very patriarchal household where you’re not allowed to be angry, what else are you going to do until you can get yourself out of that setting? So, I have a lot of respect for that survival skill that sucks. It simultaneously really sucks.

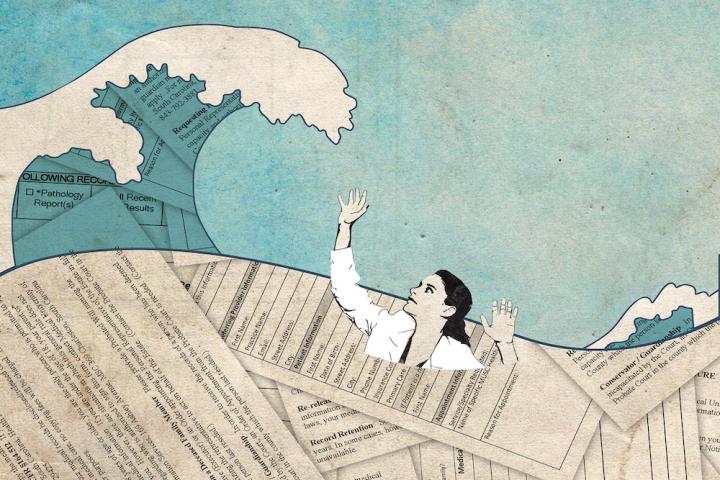

That’s one direction of it. The other direction is when we are pushed into productivity by late-stage capitalism. So you’re 20, you’re 22 and you graduate college, you go out into the world and you get an internship that’s, you know, 16-hour days and you don’t really understand what that is until you’re next to burnout, until you’re exhausted. You’re living the dream of having a full-time job and three kids and a household and you don’t know what that means until you’re next to dead. And so sometimes it’s what’s imposed upon us that keeps us from having the feelings because we’re treading water just to survive and just to keep up and to just keep up appearances and keep the kids fed and to keep the dog from dying, you know, just to keep up. So it cuts both ways. What do you think?

AA: Oh, for sure. I’m thinking of myself and so many people I know. And I love your approach to having compassion for it and seeing why people cope in this way. We’re doing the best we can with the tools we have. Absolutely.

BA: But I wouldn’t even say within the nervous system capacity we have. So this is really important. People get so mad at themselves, “Ugh, I can’t believe I stayed in that marriage, that job, that town, that religion,” that ba ba ba, but what we don’t realize is that our nervous system only has so much capacity to bend and flex. There are things that we literally cannot do because our nervous system won’t allow us to go there. So yelling at 26 year-old you as 56 year old-you for not leaving that religion and that marriage and that town is like, I have a stinky old chihuahua, it’s like getting mad at Ziggy for not doing my taxes, or getting mad at your six year-old for not doing the taxes. They do not have the capacity and you didn’t either. And “Well, I should have known better”– if someone had told you better, your neurons couldn’t have fired to make that come true because science. There’s nothing to it but because science. And this really matters to you because when we are mean to ourselves, we go into sympathetic activation. We go into fight or flight, we don’t have good thoughts, we don’t have good metabolism, we don’t have good thyroid function. Nothing works optimally within our body, within our cognition, we don’t sleep well, everything goes to hell in a handbasket when we are outside of ventral vagal for extended periods of time, when we are dysregulated on the norm, on the regular. So, why be your own bully? There are so many people out there just really stoked to bully you. Right? If you’re listening to this show, there are plenty out there. Don’t add to their pile, no?

AA: Yeah, agreed. Let’s assume that I am someone who’s in a place and I think, “Okay, yes, I can be compassionate to my past self.” And I’m kind of speaking representatively for the listeners, someone’s like, “I’m not going to be mean to myself for what I didn’t know before, but now I’m ready to learn some skills to regulate in a more positive way.” What tools do you want to hand to a listener?

BA: In order to step out of emotional outsourcing, out of dysregulation, we need to step into presence and mindfulness. Meaning, actually being in the room when you’re in the room, unless you’re choosing not to be. Because when we’re present, we can be intentional, and we can have that felt and embodied sense of agency that allows us to create the lives we want. So, where the hell do we start? We start with our morning beverage. And this is going to sound so oversimplified, and that’s exactly the point. When we’re working with the nervous system, particularly early on, we don’t want to go anywhere near the landmines. You don’t want to start thinking about, “Well, do I mindfully want to answer the phone when my mother calls?” No, no, no, no, put it away, put it away. We start with something banal, something that’s not going to activate the nervous system at all, which is: you wake up, and instead of immediately turning the coffee maker on, or the kettle, or whatever you do, you pause, you orient your nervous system, which means you look around, and you tell your nervous system when and where you are through your eyes. “Okay, I’m at home. I’m safe.” Because most of us don’t pause to let our nervous system know that. “It’s Wednesday, I’m home, I’m safe, I’m okay.” Feel your two feet – if you have two – feel your feet on the ground. Get present to the sensation of being you and your body just a little bit. If your body was the site of trauma and that’s too stressful, don’t freaking do it. Get present to the countertop. Put your hands on the countertop. It’s probably going to be cool first thing in the morning. Feel it. Or if it’s wood, feel the grain. Get present to your body and the surroundings, or inside your body, whatever’s available.

And then ask your body. “What do you want to drink?” And if it says the same thing you’ve had every day for the last 40 years, cool, whatever. I’m Argentine, I’m going to have mate. In the last couple years since doing this, I have water first, because my body’s like, “Water, water, water!” And the point is really just that moment of intentionality, awareness, and presence, and then to start filtering that through your day. So instead of just like, “There’s pizza in the break room, I guess I’ll have that for lunch,” and this New Yorker’s not out here to malign pizza, ask your body if it actually wants pizza. And you might hear, “Absolutely, go for it.” But you might hear, “No, I want a burger instead.” But what I hear constantly and chronically: “I don’t know who I am, I don’t know what I want, I’ve been living for everyone else by their rules in their stories. I don’t know what matters to me. So yeah, I’d love to not emotionally outsource, I’d love to live intentionally, but what does that begin to look like?”

This really simple tool helps us. It’s a little bridge into starting to begin to know what you want. And if you do what we call kitten steps–I think baby steps are ridiculous. I think that it’s a ridiculous thing to ask of people and I think it’s rude. What is that? Two and a half inches? Get out of here with the size of a baby’s foot. No, thank you. Too big a step. Too big a step. Kitten steps. Newborn, little teeny tiny kitten steps. That’s what we take. If you need to go slower, you can have baby turtle steps. They’re both available. Take the tiniest steps, because when we take too big a leap, we freak our nervous system out and we go back into “Lions are coming, everything’s against me, everything’s a nightmare!” What does that do? It shuts you down. You go into dorsal about it. So of course you’re not going to make change. You tried to make too big a change, silly goose! Cut it out. Back up. Back it up. Lots of tiny changes are additive and lead to sustainable, lasting change. Meow?

AA: I love it.

BA: Oh, good. I would teach another tool. Do we have time for one more little tool?

AA: Yep, please.

BA: Okay, great. We’ll both begin to reset the nervous system, retrain it to understand that what you want matters with this tool of asking yourself. Simultaneously, we honor that, of course, you’re going to get dysregulated because you’re a human. What’s optimal when the body screams “Lion!” is actually to run, is actually to push. But sometimes you’re in the carpool line, or at a PTA meeting, or in a boardroom, or in the supermarket and you can’t start screaming. O sea, you can always start screaming, that’s always available, but it’s suboptimal in terms of your entire life. So an alternative is to calm the nervous system. And I just want to be very clear: a calm nervous system is not better than any other kind of nervous system, but in this modern moment, it is sometimes necessary. It’s also smart. If you’re flying a plane, please calm your nervous system. Please don’t have a full panic attack while you’re flying a plane. You know what I mean? If you take your hands, you’re going to show your nervous system that it’s okay and safe to slow down by doing slow, patterned, repetitive motions. When we are in rumination, when we are freaking out, we are in the amygdala, we are in the lower brain, we are in the reptile mind, we need to bring ourselves back into the prefrontal cortex, the executive function part, by doing something that requires executive function like patterns and counting. So, you take your thumb and you tap your index finger and you say, “one.” You tap your New York finger and you say, “two.” You tap your ring finger and “three,” your pinky, “four,” and then you come back, 4, 3, 2, 1, but way slower. As slow as you can manage. And when you keep doing it, you start to really feel it. I mean, can you even feel it just watching me do it?

AA: Mm-hmm. I’m doing it too.

BA: You’re doing it too, yeah. It calms you just right down and allows you to make a more intentional choice, which could be, “Hey, it really hurt my feelings when you said…” Or, “No, I’m not available to take on more work right now.” Or, “I asked you to pick up the children and I expect you to keep that promise.” To advocate for yourself. That’s only really possible when we’re in a regulated nervous system, in ventral vagal, with that little bit of sympathetic that allows us to be active on our own behalf. Now, if your nervous system is shut down, if you’re checked out, if you’re overwhelmed in situations, you need to come back into the room to be present in a conversation or in a moment, you can do the same tool but faster. So 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 3, 2, 1. I feel myself picking up a little bit, so that can be really helpful. It’s also nice, you know, we started out by talking about anxiety, and limiting caffeine is one of the many smart things to do. And so it can actually be a way that I defer caffeine, by doing that a couple of times and just seeing if it perks me up enough, because it knows it gets the nervous system revved up in a very gentle way.

AA: Hmm, that’s so great. I’m also thinking that some people have caffeine addictions or a dependency and some have, again, we were talking about social media, some people will turn to various things that maybe don’t serve you. And I’m thinking that’s a really good strategy also for whatever you’re turning to that you think, “When I do that, it actually doesn’t make me feel better.” This can get you grounded again so that you can make a more intentional choice.

BA: Exactly. Yeah, for sure. It can help us stop buffering against our feelings by depending on a phone or the beverage or whatever. And I would recommend, if that’s what you’re seeking to do, to orient the nervous system first by looking around and letting your nervous system really relax into the moment.

AA: Mm-hmm. Yeah, that’s great. One more thing I wanted to ask you about is that you talk on your podcast about the idea of embodying interdependence. Could you talk about interdependence, maybe define it for us, and then talk about why cultivating this interdependence might help us break down patriarchal structures?

BA: I thought you’d never ask. We define codependent thinking, right? “You create my sense of self. You create my sense of worth and safety and belonging.” And interdependence is when we recognize ourselves and the other person with whom we’re interdependent as two autonomous animals who create their own sense of safety, worth, value, belonging, validity, and meet in the middle with mutuality and reciprocity to lift each other up, to be each other’s icing. To be each other’s support, each other’s co-regulation of their nervous system, to support each other through mutual aid. And this is the model of mutual aid and community, which is the antithesis of, well, everything we’ve been talking about in terms of whiteness as white supremacy, capitalism that demands we individually buy things and individually bootstrap our way to our own, I don’t know, survival. And of course, the patriarchy, which wants us dependent on everyone but each other, in a way, right? The patriarchy wants us dependent on it.

be each other’s support, each other’s co-regulation

So interdependence recognizes that we each have the agency to make our own choices and we get to honor each other’s choices with, of course, the caveat of doing no harm. But we get to honor each other’s choices, which the patriarchy doesn’t allow us to honor our own choices. It wants to extract our capacity to make choices because it is inherently extractive. It’s extracting labor, it’s extracting everything that it has. It’s taking with force. Whereas interdependence is about me giving where you can’t, you giving where someone else can’t, and all of us sort of balancing each other out in the middle.

It’s the friend saying, “Your skin looks really nice,” that we talked about earlier, it’s supporting each other through a tough time, it’s having each other’s back. It’s recognizing that your struggles are my struggles. In its core, and here’s the I-Married-A-Tibetan-Buddhist part of this, is that we talk all day long about non-duality in this household, and it is at its core non-dualistic to say that “I am you, you are me, we’re all the same carbon. And where you’re suffering, I can be of support, not to extract feelings or validation from you, but because I earnestly, honestly want to be of service, love, care and support to you because you matter, and you are a human, and you are also me.”

AA: Mm-hmm. Yeah, that’s a radically egalitarian vision. And I love how you said, “because we’re all carbon,” and that, at a fundamental level, it just suddenly reminded me how absurd hierarchies are among human beings. Just remembering that fundamental scientific truth, right?

BA: Yeah, we’re all carbon.

AA: We’re all carbon.

BA: It’s alright.

AA: Yeah, but we do. Humans, for whatever reason, are primates that really like hierarchies. We just build them all the time. So, yeah, it takes a lot of work to deconstruct them and to fight against that tendency. And I think some people have it stronger than others, obviously. But for people who do feel safer in a hierarchy and maybe even like a benevolent patriarchal hierarchy where they think, “Oh, no, I get it. I want to take care of you,” but in a patronizing way. But to think, “No, no, no, down here to where we’re all on the same level playing field, that we’re all on one plane together.”

BA: Right. And we all have different skills and capacities, right? We have different smarts in different ways. One of my sisters-in-law could knit you a sweater, like a whole full sweater probably in an hour and I just sit and watch her and I’m like, “Oh my God.” But if you need an IUD put in or some deep psychoanalysis, I’m your gal. And she’s not better, I’m not better, we just have different skills. And I think that gets lost in the patriarchy, too. For sure. But we need all of us.

AA: Yes. And of course, maybe this is kind of a basic thing but it’s good to remind ourselves, and I’m just thinking of conversations that I have all the time where people say, “Well, what are you saying? There’s no order to society?” So I like that you’re bringing up like, no, I can’t put an IUD in. So in that context, you have earned expertise in that area where I trust you. You are my superior in that context, where I would say, “I trust you to do what you were trained to do. Please, yes, you’re the expert here.” But then, yes, then we go to your sister-in-law for the sweaters, and you come to me for the other thing, and there’s no inherited status. It’s just what we can offer.

BA: Correct. And maybe if we all get to shine equally, then it’s like no one’s superior in any moment, it’s just the Care Bear Stare, like, “You’re the star in this moment!”

AA: Yes, yes, yes.

BA: And we can recognize it in a way as fleeting in the best way. Because that’s what’s missing in the oligarchy. You’ve got this bought or inherited status and you’re untouchable now.

AA: And it’s never questioned. Okay, so the way that we’re ending all of our episodes this season is to talk about actual action items, things we can do. And I know you’ve offered so many wonderful strategies during this episode, but if you have any real gems that you want to offer to listeners, like “here are some things that you can incorporate into your life” for our final takeaway, that would be awesome.

BA: Mind your words, mind your inputs and your outputs. We’ve been talking about what we’re taking in from social media, from the news, and how it’s dysregulating our nervous system. Be mindful. What are you repeating without intentionality? What are you saying about yourself, about your communities, about other communities? What are the stories you’re telling? And I think in part because I’ve been thinking about Cherríe and Gloria, and I’ve been thinking about the lexicon of self and the stories we tell about the self and how that creates the felt, embodied experience of being ourselves in the world. “Oh, I’m just a nurse. I’m just a mom. Oh, I’m such a ditz. Oh, I’m a negative thing. I’m such a codependent. I’m such a people-pleaser.” Really, baby? What are the stories you’re creating in your nervous system? Because every time you strengthen, every time you repeat a sentence, it becomes a belief. Beliefs are just thoughts we’ve thought over and over and over and they’re programmed into our nervous system. It becomes a neural groove. “Oh, I’m such a dummy.” Do you really want to believe that? And do you want to train the people around you to believe that? Do you want to train our daughters to believe these things about us? “Oh, if I just lost five pounds, I’d be happy then.” Mi amor, what are you choosing? This is such a core part of this somatic experience of being self, of coming into presence with self, where we get to feel into the resonance in our body of saying unkind things about ourselves, out of just habit and unintentionality. And then the next step is to notice what your body does. What’s the posture? “Ugh, I’m such a dummy.” Do you collapse? Do you tighten? Is there tension? Do you suddenly have a headache? Do you always have a headache? What is the visceral, physical response to not being kind to you? Awareness first. Yeah, thank you.

AA: Yes. Thank you so much. Well, Beatriz, can you tell us where we can find your work? Where can listeners find you on social media? Do you have books that you’d like to plug? Tell us where we can find all of the stuff you do.

BA: Well, the first place is with a present. I made a little gift for your listeners just to say thank you for being here, being part of this amazing, incredible work. If you go to my website, beatrizalbina.com/bdp – Yay! – you can download a suite of nervous system orienting exercises, inner child meditations, all sorts of goodies, just to say thank you so much for listening to the show, listening all the way through, for being here. My show is called Feminist Wellness. I am still currently on the Instagram, and you can find me there @victoriaalbinawellness

AA: Fabulous.

BA: Oh, and my book comes out, but we’ll talk about that later. It comes out at the end of September 2025, and it’s called End Emotional Outsourcing. And I am so thrilled. We’ll talk all about it.

AA: Oh, I’m so excited for that book! And thank you, thank you for that gift. That is so exciting. And we’ll have that website in the show notes on our website as well. So, Beatriz Albina, thank you so much for being here today. I learned so much from you. This was just a delight.

BA: Thanks for having me.

Get present to the sensation of being you

and your body.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!